Submitted:

25 May 2023

Posted:

26 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

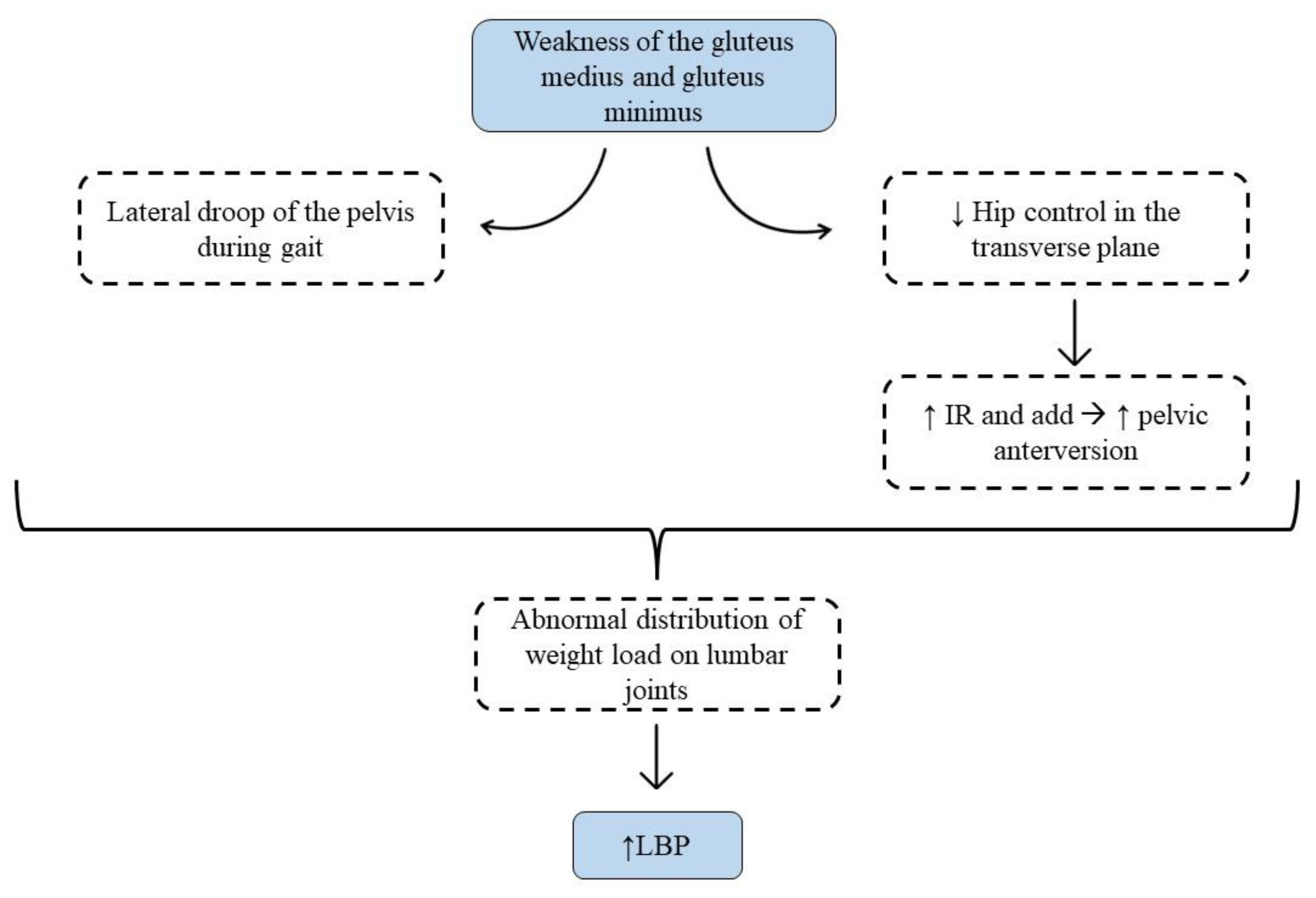

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Selection Criteria

- Inclusion Criteria

- b.

- Exclusion criteria

2.3. Extraction and synthesis of data

2.4. Assessment of methodological quality

3. Results

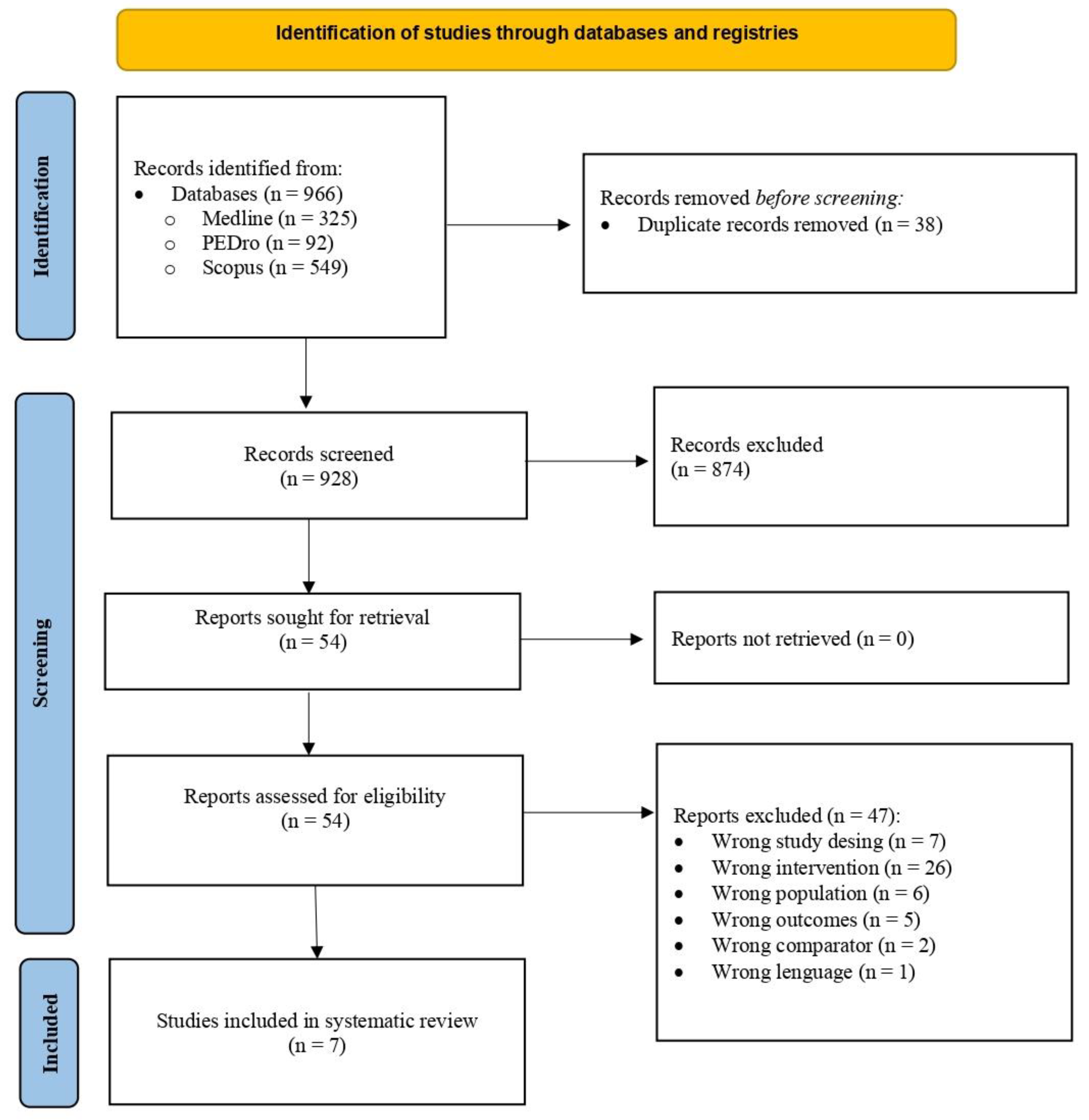

3.1. Selection of studies

3.2. Assessment of methodological quality

3.3. Characteristics of participants and interventions

3.4. Evaluation of the results

- pain

- b.

- Disability level

- c.

- Other parameters evaluated

4. Discussion

4.1. Potential applications

4.2. Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Casado-Moral, M.; Moix, J.; Vidal, J. Etiology, chronification and treatment of low back pain. Clínica y Salud 2022, 19, 379–392. [Google Scholar]

- Seguí, M.; Gérvas, J. Low Back Pain. Med Fam Semer 2002, 28, 21–41. [Google Scholar]

- Heredia-Elvar, J.R.; Segarra, V.; García-Orea, G.P.; Campillos, J.A.; Sampietro, M.; Moyano, M.; Da Silva, M.E. Proposal for the Design of Functional Rehabilitation Programs in the Population with Low Back Pain by the Physical Exercise Specialist. Int J Phys Exerc Heal Sci Trainers 2016.

- Katz, J.N. Lumbar disc disorders and low-back pain: socioeconomic factors and consequences. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006, 88, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moix, J.; Cano-Vindel, A. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline for nonspecific low back pain. Ansiedad y estres 2006, 12, 116–128. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, G.A.; Salas, J.D.Z. Exercise as a treatment for low back pain management. Rev Salud Publica (Bogota) 2017, 19, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marín-Peña, O.; Fernández-Tormos, E.; Dantas, P.; Rego, P.; Pérez-Carro, L. Anatomy and function of the coxofemoral joint. Arthroscopic anatomy of the hip. Rev Española Artrosc y Cirugía Articul 2016, 23, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatefi, M.; Babakhani, F.; Ashrafizadeh, M. The effect of static stretching exercises on hip range of motion, pain, and disability in patients with non-specific low back pain. J Exp Orthop 2021, 8, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, A.H.; Hukins, D.W.L. Lower limb involvement in spinal function and low back pain. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 2009, 22, 219–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadler, S.F.; Malanga, G.A.; Bartoli, L.A.; Feinberg, J.H.; Prybicien, M.; Deprince, M. Hip muscle imbalance and low back pain in athletes: influence of core strengthening. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2002, 34, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jesus, F.L.A.; Fukuda, T.Y.; Souza, C.; Guimarães, J.; Aquino, L.; Carvalho, G.; Powers, C.; Gomes-Neto, M. Addition of specific hip strengthening exercises to conventional rehabilitation therapy for low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil 2020, 34, 1368–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzleff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; Chou, R.; Glanville, J.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Lalu, M.M.; Li, T.; Loder, E.W.; Mayo-Wilson, E.; McDonald, S.; McGuinness, L.A.; Stewart, L.A.; Thomas, J.; Tricco, A.C.; Welch, V.A.; Whiting, P.; Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moseley, A.M.; Elkins, M.R.; Van der Wees, P.J.; Pinheiro, M.B. Using research to guide practice: The Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro). Brazilian J Phys Ther 2020, 24, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello, J.B.; Maciá, L. Critical reading of clinical evidence. 2015, 184.

- Bade, M.; Cobo-Estevez, M.; Neeley, D.; Pandya, J.; Gunderson, T.; Cook, C. Effects of manual therapy and exercise targeting the hips in patients with low-back pain-A randomized controlled trial. J Eval Clin Pract 2017, 23, 734–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Yim, J. Core Stability and Hip Exercises Improve Physical Function and Activity in Patients with Non-Specific Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Tohoku J Exp Med 2020, 251, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, U.C.; Sim, J.H.; Kim, C.Y.; Hwang-Bo, G.; Nam, C.W. The effects of gluteus muscle strengthening exercise and lumbar stabilization exercise on lumbar muscle strength and balance in chronic low back pain patients. J Phys Ther Sci 2015, 27, 3813–3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Kim, S.Y. Effects of hip exercises for chronic low-back pain patients with lumbar instability. J Phys Ther Sci 2015, 27, 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Yang, Y.; Kong, P.W. Comparison of Lower Limb and Back Exercises for Runners with Chronic Low Back Pain. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2017, 49, 2374–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, T.Y.; Aquino, L.M.; Pereira, P.; Ayres, I.; Feio, A.F.; de Jesus, F.L.A.; Gomes-Neto, M. Does adding hip strengthening exercises to manual therapy and segmental stabilization improve outcomes in patients with nonspecific low back pain? A randomized controlled trial. Brazilian J Phys Ther 2021, 25, 900–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, K.D.; Emery, C.A.; Wiley, J.P.; Ferber, R. The effect of the addition of hip strengthening exercises to a lumbopelvic exercise programme for the treatment of non-specific low back pain: A randomized controlled trial. J Sci Med Sport 2015, 18, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, S.N.; Carr, D.B.; Cohen, M.; Finnerup, N.B.; Flor, H.; Gibson, S.; Keefe, J.S.; Mogil, J.S.; Ringkamp, M.; Sluka, K.A.; Song, X.J.; Stevens, B.; Sullivan, M.D.; Tutelman, P.R.; Ushida, T.; Vader, K. The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain 2020, 161, 1976–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romera, E.; Perena, M.; Perena, M.; Rodrigo, M. Pain neurophysiology. Rev Soc Esp Dolor 2000, 7, 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Santiago, C.; Perez, K.; Castro, N. Low back pain and its relation to disability index in a rehabilitation hospital. Rev Cient Méd 2018, 21, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Salvetti, M.G.; Pimenta, C.A.; Braga, P.E.; Corrêa, C.F. Disability related to chronic low back pain: prevalence and associated factors. Rev da Esc Enferm da USP 2012, 46, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadler, S.; Cassidy, S.; Peterson, B.; Spink, M.; Chuter, V. Gluteus medius muscle function in people with and without low back pain: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tataryn, N.; Simas, V.; Catterall, T.; Furness, J.; Keogh, J.W.L. Posterior-Chain Resistance Training Compared to General Exercise and Walking Programmes for the Treatment of Chronic Low Back Pain in the General Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sport Med 2021, 7, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainville, J.; Hartigan, C.; Jouve, C.; Martinez, E. The influence of intense exercise-based physical therapy program on back pain anticipated before and induced by physical activities. Spine J 2004, 4, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, A.; Spink, M.; Ho, A.; Chuter, V. Exercise interventions for the treatment of chronic low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clin Rehabil 2015, 29, 1155–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Ítem | Total | ||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | ||

| Bade M et al. 2016 [15] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | p < 0.05 | Yes | Yes | Yes | 9 |

| Cai C et al. 2017 [19] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 95%CIp < 0.01 | No | Yes | Yes | 9 |

| Fukuda TY et al. 2021 [20] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | 95% CI | Yes | Yes | No | 8 |

| Jeong UC et al. 2015 [17] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | p < 0.01 | No | Yes | Yes | 9 |

| Kendal KD et al. 2014 [21] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | 95% CI | Yes | Yes | No | 8 |

| Kim B et al. 2020 [16] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | p < 0.05 | Yes | Yes | Yes | 10 |

| Lee SW et al. 2014 [18] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | p < 0.01 | Yes | Yes | Yes | 10 |

| Study | Ítem | Total | ||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | ||

| Bade M et al. 2016 [15] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| Cai C et al. 2017 [19] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| Fukuda TY et al. 2021 [20] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 9 |

| Jeong UC et al. 2015 [17] | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| Kendall KD et al. 2014 [21] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 9 |

| Kim B et al. 2020 [16] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 9 |

| Lee SW et al. 2014 [18] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| First author, year and country of publication | Study design | Participants (baseline sample side and characteristics) | Intervention | Outcomes | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bade M et al. 2017, USA [15] | Random controlled trial | ni=90 (37♀ y 53♂) NSLBP ≥ 2 in NPRS and disability ≥ 20% in ODI. CG: ni =43; 16♀ y 27♂ (11 dropout → nf =32) Age (mean ± SD): 48,1 ± 2,4 y Height (mean ± SD): 1,7 ± 0,0m Weight (mean ± SD): 78,5 ± 3,1 Kg Symptoms duration (media ± SD): 19,7 ± 7,2 Wk IG: ni =47; 21♀ y 26♂ (7 dropout → nf =40) Age (mean ± SD): 44,8 ± 2,3 y Height (mean ± SD): 1,7 ± 0,0m Weight (mean ± SD): 81,3 ± 4,7 Kg Symptoms duration (media ± SD): 20,3 ± 6,5 Wk |

CG: MT, coordination, strengthening and resistance trunk ex., PNS mobilizations, tractions, aerobic ex., flexion ex., fitness, centralization and directional preference ex. and procedures. GI: CG Intervention + HM strengthening + hip MT (mobilizations degree III-IV, 30 sec/technique; A-P mobilization with traction, traction and mobilization P-A in PP) |

Pain: NPRS Disability: ODI GROC PASS |

CG: Changes with baseline ↓ NPRS ↓ ODI IG: Changes with baseline ↓ NPRS ↓ ODI GI vs GC ↓* NPRS ↓* ODI ↓* GROC ↔ PASS |

| Cai C et al. 2017, Singapore [19] | Random controlled trial, simple blind | ni =84 (42♀ y 42♂) NSCLBP CG: -LE: ni =28 (4 dropout → nf =24) Age (mean ± SD): 26,1 ± 4,1 y Weight (mean ± SD): 61,7 ± 10,8 Kg BMI (mean ± SD): 21,8 ± 2,4 Kg/m2 -LS: ni =28 (3 dropout → nf =25) Age (mean ± SD): 26,9 ± 6,4 y Weight (mean ± SD): 60,3 ± 12,1 Kg BMI (mean ± SD): 21,9 ± 2,4 Kg/m2 IG: ni =28 (3 dropout → nf = 25) Age (mean ± SD): 28,9 ± 5,3 y Weight (mean ± SD): 61,7 ± 12,6 Kg BMI (mean ± SD): 21,7 ± 2,4 Kg/m2 |

CG: -LE: Lumbar extensor strengthening ex. -LS: lumbopelvic motor control ex. IG: HM and knee strengthening ex. |

Pain: NPRS Disability: PSFS LL strength: dynamometry LE resistance: EMG Activation of trunk stabilizing muscles: US |

CG (LE y LS): Changes with baseline ↓* NPRS ↑* PSFS ↑ LL strength ↑* LE resistance ↑* Activation of trunk stabilizing muscles IG: Changes with baseline ↓* NPRS ↑* PSFS ↑* LL strength ↑* LE resistance ↑* Activation of trunk stabilizing muscles IG vs CG (LE y LS) ↓* NPRS ↑* PSFS ↑ LL strength ↑* LE endurance ↔ Activation of trunk stabilizing muscles |

| Fukuda TY et al. 2021, Brazil [20] | Random controlled trial, simple blind | ni =70 (37♀ y 33♂) NSCLBP CG: ni =35 (3 dropout → nf =32) Age (mean ± SD): 35,2 ± 12,5 y Height (mean ± SD): 1,6 ± 0,1m Weight (mean ± SD): 72,6 ± 15,6 Kg BMI (mean ± SD): 25,3 ± 4,6 Kg/m2 Symptoms duration (mean ± SD): 6,9 ± 8,1 month IG: ni =35 (4 dropout → nf =31) Age (mean ± SD): 40,2 ± 12,4 y Height (mean ± SD): 1,7 ± 0,1m Weight (mean ± SD): 75,8 ± 15,9 Kg BMI (mean ± SD): 25,9 ± 5,4 Kg/m2 Symptoms duration (mean ± SD): 8,1 ± 8,9 month |

CG: MT (P-A-C mobilization degree III of L1-L5, 5 reps/1min following Maitland method and myofascial liberation) Segmentary lumbar stabilization ex. IG: CG intervention + HM strengthening ex. |

Pain: VAS Disability: RMDQ HM strength: dynamometry Kinematic analysis of gait (LL, trunk and pelvis) |

CG: Changes with baseline ↓ VAS ↓ RMDQ ↑ HM strength ↔ Kinematic analysis IG: changes with baseline ↓ VAS ↓ RMDQ ↑ HM strength ↔ Kinematic analysis IG vs CG ↔ VAS ↔ RMDQ ↔ HM strength ↔ Kinematic analysis |

| Jeong UC et al. 2015, Korea [17] | Random controlled trial | ni =40♀ NSLBP ≥ 5 in VAS and disability ≥ 20% in ODI. CG: ni =20♀ (0 dropout → nf =20) Age (mean ± SD): 41,2 ± 6,7 y Height (mean ± SD): 159,9 ± 4,7cm Weight (mean ± SD): 56,6 ± 4,2 Kg IG: ni =20♀ (0 dropout → nf =20) Age (mean ± SD): 41,2 ± 5,5 y Height (mean ± SD): 161,5 ± 6,0 cm Weight (mean ± SD): 59,7 ± 7,2 Kg |

CG: Lumbar stabilization ex. (2 sets/20reps/10 sec) IG: CG intervention + HM strengthening ex. |

Disability: ODI Lumbar strength: M3 Balance: Tetrax |

CG: Changes with baseline ↓ ODI ↑ Lumbar strength ↑ Balance IG: Changes with baseline ↓ ODI ↑Lumbar strength ↑ Balance IG vs CG ↓* ODI ↑* Lumbar strength ↑* Balance |

| Kendall KD et al. 2014, Canada [21] | Random controlled trial | ni =80 (42♀ y 38♂) NSCLBP ≥ 5 in VAS CG: ni =40; 18♀ y 22♂ (4 dropout → nf =36) Age (95%CI): 33 (33, 41) y Height (95%CI): 172 (169, 175) cm Weight (95%CI): 73 (68, 78) Kg Symptoms duration (95%CI): 4 (3, 6) y IG: ni =40; 24♀ y 16♂ (5 dropout → nf =35) Age (95%CI): 41 (37, 45) y Height (95%CI): 170 (167, 173) cm Weight (95%CI): 77 (71, 83) Kg Symptoms duration (95%CI): 7 (4, 10) y |

CG: Lumbopelvic motor control (transverse, multifidus and pelvic floor coordination) IG: CG intervention + HM strengthening ex. |

Pain: VAS Disability: ODI HM strength: Dynamometry Trendelenburg Test |

CG: Changes with baseline ↓* VAS ↓* ODI ↔ HM strength ↔ Trendelenburg Test IG: Changes with baseline ↓* VAS ↓* ODI ↑* HM strength ↔ Trendelenburg Test IG vs CG ↔ VAS ↔ ODI ↑* HM strength ↔ Trendelenburg test |

| Kim B et al. 2020, Korea [16]. | Randomized controlled trial, doble blind | ni =75 (32♀ y 34♂) NSCLBP ≥ 3 in VAS CG: ni =25 (5 dropout → nf =20) Age (mean ± SD): 47,7 ± 8,5 y Height (mean ± SD): 167,7 ± 8,1cm Weight (mean ± SD): 67,6 ± 8,7 Kg BMI (media ± SD): 23,9 ± 1,0 Kg/m2 IG: -SIG: ni =25 (3 dropout → nf =22) Age (mean ± SD): 47,0 ± 9,4 y Height (mean ± SD): 166,5 ± 2,1 cm Weight (mean ± SD): 66,0 ± 9,2 Kg BMI (mean ± SD): 23,6 ± 1,5 Kg/m2 -FIG: ni =25 (1 dropout → nf =24) Age (mean ± SD): 47,5 ± 9,7 y Height (mean ± SD): 164,7 ± 8,2 cm Weight (mean ± SD): 65,4 ± 10,4 Kg BMI (mean ± SD): 23,9 ± 1,6 Kg/m2 |

CG: Core stability ex. (30 min, 3 session/sem, 6 sem, 10reps/7-8sec) Placebo (light palpation of the lumbosacral region) IG: -SIG: core stability ex. + HM strengthening ex. FIG: core stability ex. + HM static stretching ex. |

Pain: VAS Disability: ODI y RMDQ Lumbar instability: PSLRT HM flexibility: TTT, MTT, OT, FAIRT Balance: OLST QoL: SF-36 |

CG: Changes with baseline ↓* VAS ↓* ODI y RMDQ ↑*PSLRT ↑* HM flexibility ↑* OLST ↑* SF-36 SIG y FIG: Changes with baseline ↓* VAS ↓* ODI y RMDQ ↑*PSLRT ↑* HM flexibility ↑* OLST ↑* SF-36 SIG vs CG ↓* VAS ↓* ODI y RMDQ ↔PSLRT ↔ HM flexibility ↑* OLST ↑* SF-36 FIG vs CG ↓* VAS ↓* ODI y RMDQ ↑*PSLRT ↑* HM flexibility ↑* OLST ↑* SF-36 FIG vs SIG ↔VAS ↔ ODI y RMDQ ↑*PSLRT ↑* HM flexibility ↔ OLST ↔ SF-36 |

| Lee SW et al. 2014, Korea [18]. | Randomized controlled trial | ni =78 CLBP CG: ni =31 (6 dropout → nf = 25) -CGLS: ni =20 (4 dropout → nf =16) Age (mean ± SD): 50,0 ± 11,4 y Height (mean ± SD): 161,9 ± 7,7 cm Weight (mean ± SD): 60,9 ± 9,8 Kg BMI (mean ± SD): 23,2 ± 2,8 Kg/m2 -CGIN: ni =11 (2 dropout → nf =9) Age (mean ± SD): 59,3 ± 17,3 y Height (mean ± SD): 161,0 ± 8,3 cm Weight (mean ± SD): 59,5 ± 10,0 Kg BMI (mean ± SD): 22,8 ± 2,9 Kg/m2 IG: ni = 47 (3 dropout → nf =44) -IGLS: ni =25 (2 dropout → nf =23) Age (mean ± SD): 54,9 ± 10,6 y Height (mean ± SD): 161,0 ± 7,1 cm Weight (mean ± SD): 61,9 ± 9,8 Kg BMI (mean ± SD): 23,8 ± 2,8 Kg/m2 -IGIN: ni =22 (1 dropout → nf =21) Age (mean ± SD): 61,0 ± 13,2 y Height (mean ± SD): 159,7 ± 6,0 cm Weight (mean ± SD): 59,4 ± 8,9 Kg BMI (mean ± SD): 23,3 ± 2,6 Kg/m2 |

CG: Lumbar stability ex. (4 ex./ 4 sets/ 4reps/ 10 sec, 30 sec rest. IG: CG intervention + HM strengthening ex. + hip mobility ex. |

Pain: VAS Disability: modified ODI |

CG: Changes with baseline ↓* VAS ↓* ODI IG: Changes with baseline ↓* VAS ↓* ODI IG vs CG ↓ VAS ↓ ODI |

| First author, year and country of publication | Exercise | Volume and intensity | Frequency (days/week) | Time (minutes/session) | Duration (weeks) | Supervision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bade M et al. 2017, USA. [15] | Clam in side lying with ER Quadruped hip extension Unilateral bridge Home ex. |

2 sets of 12-15 reps | 7 -Home ex. Twice a day |

- | - | Yes -Home ex. with instructions |

| Cai C et al. 2017, Singapore [19] | Device for strengthening hip abd and extensor and knee extensor Home ex.: -single-leg squat -Wall sit |

Supervised: 3 sets of 10 reps, 2 min rest 10 RM Home ex.: 3 sets of 10 rep, 2,5Kg single-leg squat, 5Kg wall sit |

Supervised:2 Home ex.: 5 |

45 | 8 | Yes -Home ex. with instructions |

| Fukuda et al. 2021, Brazil [20] | Clam in side lying with ER Lateral straight leg rise with ankle weight Squat with ER Monster Walk with ER |

3 sets of 10 reps 70% RM Ex. with ER: maximum resistance that enables 10 reps |

2 | 45 | 5 | Yes |

| Jeong UC et al. 2015, Korea [17] | Gluteus maximus and gluteus medius ex. 3 wk without resistance and 3 wk with resistance | 2 sets of 15 reps | 3 | 50 | 6 | Yes |

| Kendal KD et al. 2014, Canada [21] | Controlled with US (not specified) Home ex.: open and close kinetic chain hip ex. |

Not specified |

Supervised:1 Home ex.: Not specified |

Not specified | 6 | Yes -Home ex. with instructions |

| Kim B et al 2020, Korea [16] | FIG: HM static stretching (hamstring, iliopsoas, piriformis, tensor fasciae latae) SIG: HM strengthening ex. (side lying hip abd with IR, prone heel squeeze, quadruped hip extension, standing gluteal squeeze) |

3 reps of 30 sec 10 sec rest |

3 | 45 | 6 | Yes |

| Lee SW et al. 2014, Korea [18] | To increase ROM: 4 open kinetic chain hip ex. 6 strengthening ex. with ER |

3 sets of 10 reps, 1 min rest 75% RM |

3 | ROM ex.: 20 Strengthening ex.: Not specified |

6 | Yes |

| Warm-up | Central part | Return to calm | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exercises | Joint mobility Muscular activation |

HM strengthening: Squat Monster Walk Quadruped hip extension Clam in side lying Bridge |

Relax Static stretch Manual therapy |

| Intensity | Minimum | 75-80% RM | |

| Volume | 2-3 sets / 8-12 reps for ex. 1 minute rest |

||

| Time | 5-10 minutes | 45-50 minutes | 5-10 minutes |

| Frequency | 3-4 days/week, with 1-2 days of rest between sessions. | ||

| Observations | The volume and intensity should be increased as the patient improves, increasing the number of repetitions and/or loads (elastic resistance or weight) | ||

| Abbreviations | RM: maximal repetition; reps: repetitions | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).