Submitted:

24 May 2023

Posted:

26 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Selection of instruments

- 1)

- workplace aggression i.e., “efforts by individuals to harm others with whom they work, or have worked, or the organizations in which they are currently, or were previously, employed. This harm- doing is intentional and includes psychological as well as physical injury” (p. 38). (Baron & Neuman, 1996);

- 2)

- bullying i.e., “harassing, offending, socially excluding someone or negatively affecting someone’s work. It has to occur repeatedly and regularly (e.g., weekly) and over a period of time (e.g., about six months). Bullying is an escalating process in the course of which the person confronted ends up in an inferior position becoming the target of systematic negative social acts. A conflict cannot be called bullying if the incident is an isolated event or if two parties of approximately equal ‘strength’ are in conflict’’ (p.26) (Einarsen et al., 2020);

- 3)

- mobbing i.e., “situations where a worker, supervisor, or manager is systematically and repeatedly mistreated and victimized by fellow workers, subordinates, or superiors. The term is widely used in situations where repeated aggressive and even violent behavior is directed against an individual over some period of time.” (p.379) (Einarsen, 2000);

- 4)

- harassment/discrimination i.e., “interpersonal behavior aimed at intentionally harming another employee in the workplace” (p.998) (Bowling & Beehr, 2006);

- 5)

- workplace deviance i.e., “voluntary behavior that violates significant organizational norms and, in so doing, threatens the well-being of the organization or its members, or both” (p.555) ( Robinson & Bennett, 1995);

- 6)

- counterproductive work behavior i.e., “volitional acts that harm or are intended to harm organizations or people in organizations” (p. 151) (Spector & Fox, 2005);

- 7)

- workplace violence i.e., “the act or threat of violence, ranging from verbal abuse to physical assaults directed toward persons at work or on duty. The impact of workplace violence can range from psychological issues to physical injury, or even death” (p.1) (NIOSH, 2023);

- 8)

- abuse i.e., “interactions between organizational members that are repeated hostile verbal and nonverbal, often nonphysical behaviors directed at a person(s) such that the target’s sense of him/herself as a competent worker and person is negatively affected” (p.212) (Keashly, 2001)

- 9)

- terror i.e., "hostile and unethical communication which is directed in a systematic way by one or a number of persons mainly toward one individual. These actions take place often (almost every day) and over a long period (at least for six months) and, because of this frequency and duration, result in considerable psychic, psychosomatic and social misery" (p.120) (Leymann, 1990).

- 10)

- injustice i,e., violating distributive, procedural, interpersonal rules (Colquitt & Rodell, 2015).- Distributive injustice i.e., “ dissatisfaction and low morale related to a person’s suffering injustice in social exchanges… felt injustice is a response to a discrepancy between what is perceived to be and what is perceived should be (e.g., effort and reward, allocation of scarce rewards between different people)” (p. 272) (Adams, 1965);- Procedural justice i.e., “members’ sense of the moral propriety of how they are treated—is the “glue” that allows people to work together effectively. Justice defines the very essence of individuals’ relationship to employers. (p.34). In contrast, injustice (e.g., inconsistent treatment, discrimination or ill-treatment, imprecision, ethical flaw, or prejudice), is like a corrosive solvent that can dissolve bonds within the community. Injustice is hurtful to individuals and harmful to organizations” (p. 36) (Cropanzano et al., 2007); -.Interpersonal Justice i.e., “treating an employee with dignity, courtesy, and respect” This includes “informational justice: sharing relevant information with employees.” (p.36) (Cropanzano et al., 2007).

- 11)

- interpersonal conflict i.e., “range from minor disagreements between coworkers to physical assaults on others. The conflict may be overt (e.g., being rude to a coworker) or may be covert (e.g., spreading rumors about a coworker)” (p.357) (Spector & Jex, 1998);

- 12)

- victimization i.e., “an employee’s perception of having been the target, either momentarily or over time, of emotionally, psychologically, or physically injurious actions by another organizational member with whom the target has an ongoing relationship” (p.1023) (Aquino & Lamertz, 2004); -scapegoating: i.e., “an extreme form of prejudice in which an outgroup is unfairly blamed for having intentionally caused an ingroup’s misfortunes” (p.244) (Glick, 2005);

- 13)

- micropolitics i.e.,” referring to employees’ perceptions in organizations, they often describe political behaviors in negative terms and associate these with self-serving behaviors, usually at the expense of others” (p.139) (Poon, 2003);

- 14)

- ostracism i.e., “the exclusion, rejection, or ignoring of an individual (or group) by another individual (or group) that hinders one’s ability to establish or maintain positive interpersonal relationships, work-related success, or favorable reputation within one’s place of work” (p.217) (Hitlan et al., 2006);

- 15)

- incivility i.e., “low-intensity deviant behavior with ambiguous intent to harm the target, in violation of workplace norms for mutual respect. Uncivil behaviors are characteristically rude and discourteous, displaying a lack of regard for others” (p.457) (Andersson & Pearson, 1999);

- 16)

- social safety i.e., “in a systemic or socio-ecological approach (Barboza et al., 2009; Ferrer et al., 2011)), the dyad (victim and perpetrator), the triad (dyad and bystander) and the group are placed in larger systems around them such as the school, neighborhood and society. Therefore, power relations are influenced by the cultural and social context (Carrera et al., 2011)” (p.109) (Broersen et al., 2015)

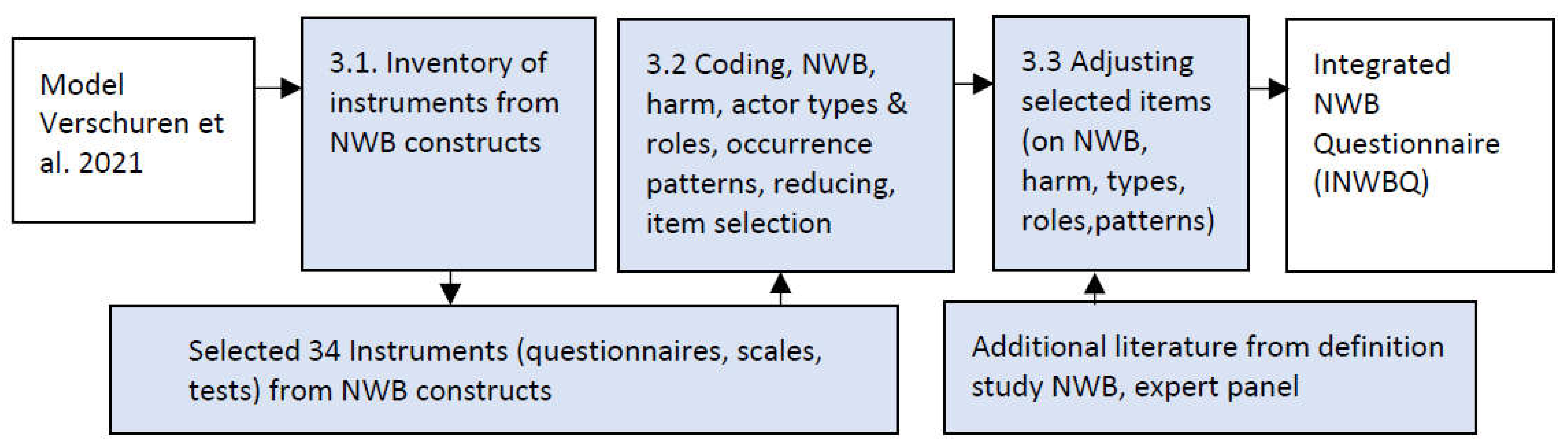

2.2. Description of steps in developing the INWBQ

Coding decisions

3. Results

3.1. Inventory of instruments

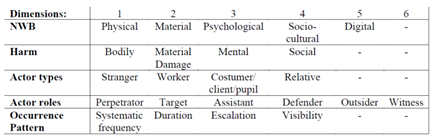

3.2. Dimensions and item selection for NWB, Harm, Actor types & roles

3.2.1. Dimensions NWB

3.2.2. Dimensions Harm

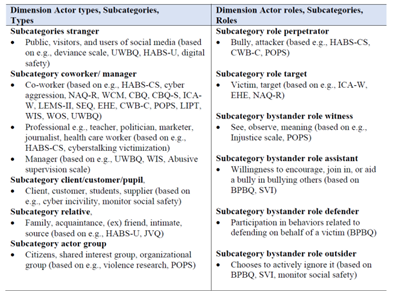

3.2.3. Dimension actor types

3.2.4. Dimension actor roles

3.2.5. Occurrence patterns

Systematic

Duration

Escalation

Visibility

3.3.6. Adjustments

3.3.7. Expert panel

3.3.8. INWBQ

4. Discussion

4.1. Scientific implications

4.2. Practical implication

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Future research

5. Conclusion

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Adams, J. S. (1965). Inequity In Social Exchange. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 2, Number C, pp. 267–299). [CrossRef]

- Alhabash, S.; McAlister, A.R.; Hagerstrom, A.; Quilliam, E.T.; Rifon, N.J.; Richards, J.I. Between Likes and Shares: Effects of Emotional Appeal and Virality on the Persuasiveness of Anticyberbullying Messages on Facebook. Cyberpsychology, Behav. Soc. Netw. 2013, 16, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, L.M.; Pearson, C.M. Tit for Tat? The Spiraling Effect of Incivility in the Workplace. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, K.; Lamertz, K. A Relational Model of Workplace Victimization: Social Roles and Patterns of Victimization in Dyadic Relationships. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 1023–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas, A.; Giorgi, G.; Montani, F.; Mancuso, S.; Perez, J.F.; Mucci, N.; Arcangeli, G. Workplace Bullying in a Sample of Italian and Spanish Employees and Its Relationship with Job Satisfaction, and Psychological Well-Being. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvey, R.D.; Cavanaugh, M.A. Using Surveys to Assess the Prevalence of Sexual Harassment: Some Methodological Problems. J. Soc. Issues 1995, 51, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatar, Z.B.; Yuksel, S. Mobbing at Workplace - Psychological Trauma and Documentation of Psychiatric Symptoms. Noro Psikiyatr. Arsivi 2018, 56, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboza, G.E.; Schiamberg, L.B.; Oehmke, J.; Korzeniewski, S.J.; Post, L.A.; Heraux, C.G. Individual Characteristics and the Multiple Contexts of Adolescent Bullying: An Ecological Perspective. J. Youth Adolesc. 2009, 38, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R. A., & Neuman, J. H. (1996). Workplace violence and workplace aggression: Evidence on their relative frequency and potential causes. Aggressive Behavior, 22(3), 161–173. [CrossRef]

- Bayramoğlu, M.M.; Toksoy, D. Leadership and Bullying in the Forestry Organization of Turkey. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Brown, G. Beck Depression Inventory–II; Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R.J.; Robinson, S.L. Development of a measure of workplace deviance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Björkqvist, K.; Österman, K.; Lagerspetz, K.M.J. Sex differences in covert aggression among adults. Aggress. Behav. 1994, 20, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, S. M., Creese, S., Guest, R. M., Pike, B., Saxby, S. J., Fraser, D. S., Stevenage, S. V, & Whitty, M. T. (2012). Superidentity: Fusion of identity across real and cyber domains. Global Forum on Identity, ID 360, 1–10. https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/336645/1/ID360_-_finalpaper.pdf.

- Bougie, R., & Sekaran, U. (2020). Research methods for business: A skill building approach (8th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. Inc. https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Research+Methods+For+Business%3A+A+Skill+Building+Approach%2C+8th+Edition-p-9781119561248.

- Bowling, N.A.; Beehr, T.A. Workplace harassment from the victim's perspective: A theoretical model and meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 998–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broersen, A., Ossenblok, A., & Montesano Montessori, N. (2015). Pesten en sociale veiligheid op scholen: definities en keuzes op micro-, meso- en macroniveau [Bullying and social safety in schools: definitions and choices at micro, meso and macro level]. Tijdschrift Voor Orthopedagogiek, 54(54), 108–119. http://schoolpsychologencongres.nl/images/presentaties/Bijbehorend-artikel-wokshop-Annemiek-Broersen.pdf.

- Campo, V.R.; Klijn, T.P. Verbal abuse and mobbing in pre-hospital care services in Chile. Rev. Latino-Americana de Enferm. 2018, 25, e2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannavò, M.; La Torre, F.; Sestili, C.; La Torre, G.; Fioravanti, M. Work Related Violence As A Predictor Of Stress And Correlated Disorders In Emergency Department Healthcare Professionals. Clin. Ther. 2019, 170, e110–e123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera, M.V.; DePalma, R.; Lameiras, M. Toward a More Comprehensive Understanding of Bullying in School Settings. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 23, 479–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cele, B. (2018). Addendum to the saps annual report. South African Police Service. https://nationalgovernment.co.za/department_annual/296/2019-south-african-police-service-(saps)-annual-report.pdf.

- Cheung, T.; Lee, P.H.; Yip, P.S.F. The association between workplace violence and physicians’ and nurses’ job satisfaction in Macau. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0207577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Codina, M.; Pereda, N.; Guilera, G. Lifetime Victimization and Poly-Victimization in a Sample of Adults With Intellectual Disabilities. J. Interpers. Violence 2020, 37, 2062–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colquitt, J. A., & Rodell, J. B. (2015). Measuring justice and fairness. In R. S. Cropanzano & M. L. Ambrose (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Justice in the Workplace (Number March 2019, pp. 1–30). Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Couper, M.P.; Traugott, M.W.; Lamias, M.J. Web Survey Design and Administration. Public Opin. Q. 2001, 65, 230–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cropanzano, R.; Bowen, D.E.; Gilliland, S.W. The Management of Organizational Justice. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2007, 21, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, R.S. A Meta-Analysis of the Relationship Between Organizational Citizenship Behavior and Counterproductive Work Behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 1241–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demaray, M.K.; Summers, K.H.; Jenkins, L.N.; Becker, L.D. Bullying Participant Behaviors Questionnaire (BPBQ): Establishing a Reliable and Valid Measure. J. Sch. Violence 2016, 15, 158–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSouza, E.R. Frequency Rates and Correlates of Contrapower Harassment in Higher Education. J. Interpers. Violence 2011, 26, 158–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsen, S. Harassment and bullying at work: A review of the scandinavian approach. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2000, 5, 379–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsen, S.; Hoel, H.; Notelaers, G. Measuring exposure to bullying and harassment at work: Validity, factor structure and psychometric properties of the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised. Work. Stress 2009, 23, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsen, S, Hoel, H., Zapf, D., & Cooper, C. L. (2011). Bullying and harassment in the workplace: Developments in theory, research, and practice (Second). CRC Press. ISBN 9781439804896 - CAT# K10270.

- Einarsen, S.; Skogstad, A. Bullying at work: Epidemiological findings in public and private organizations. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 1996, 5, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsen, Ståle V., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., & Cooper, C. L. (2020). The concept of bullying and harassment at work: The european tradition. In S. V. Einarsen, H. Hoel, D. Zapf, & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Bullying and harassment in the workplace: Theory, Research and Practice (pp. 3–41). CRC Press.

- Elovainio, M.; Kivimäki, M.; Vahtera, J. Organizational Justice: Evidence of a New Psychosocial Predictor of Health. Am. J. Public Heal. 2002, 92, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escartín, J.; Monzani, L.; Leong, F.; Rodríguez-Carballeira. A reduced form of the Workplace Bullying Scale – the EAPA-T-R: A useful instrument for daily diary and experience sampling studies. Work. Stress 2017, 31, 42–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escartín, J.; Rodríguez-Carballeira, A.; Zapf, D.; Porrúa, C.; Martín-Peña, J. Perceived severity of various bullying behaviours at work and the relevance of exposure to bullying. Work. Stress 2009, 23, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escartín, J., Vranjes, I., Baillien, E., & Notelaers, G. (2021). Workplace Bullying and Cyberbullying Scales: An Overview. In R. C. D’Cruz P., Noronha E., Notelaers G. (Ed.), Concepts, Approaches and Methods. Handbooks of Workplace Bullying, Emotional Abuse and Harassment (1st ed., pp. 325–368). Springer, Singapore.

- Every-Palmer, S.; Barry-Walsh, J.; Pathé, M. Harassment, stalking, threats and attacks targeting New Zealand politicians: A mental health issue. Aust. New Zealand J. Psychiatry 2015, 49, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, S.; Coyne, I.; Axtell, C.; Sprigg, C. Design, development and validation of a workplace cyberbullying measure, the WCM. Work. Stress 2016, 30, 293–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, B.M.; Ruiz, D.M.; Amador, L.V.; Orford, J. School Victimization Among Adolescents. An Analysis from an Ecological Perspective. Psychosoc. Interv. 2011, 20, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, S.; Spector, P.E.; Miles, D. Counterproductive Work Behavior (CWB) in Response to Job Stressors and Organizational Justice: Some Mediator and Moderator Tests for Autonomy and Emotions. J. Vocat. Behav. 2001, 59, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredericksen, E.D.; McCorkle, S. Explaining Organizational Responses to Workplace Aggression. Public Pers. Manag. 2013, 42, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, M., Couper, M. P., & Hansen, S. E. (2000). Technology effects: Do capi or Papi interviews take longer? Journal of Official Statistics, 16(3), 273–286. https://www.scb.se/contentassets/f6bcee6f397c4fd68db6452fc9643e68/technology-effects-do-capi-or-papi-interviews-take-longer.pdf.

- Furnell, S. (2002). Cybercrime: Vandalizing the information society. Addison-Wesley.

- Garthus-Niegel, S.; Nübling, M.; Letzel, S.; Hegewald, J.; Wagner, M.; Wild, P.S.; Blettner, M.; Zwiener, I.; Latza, U.; Jankowiak, S.; et al. Development of a mobbing short scale in the Gutenberg Health Study. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Heal. 2016, 89, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giga, S. I., Hoel, H., & Lewis, D. (2008). The costs of workplace bullying. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260246863_The_Costs_of_Workplace_Bullying.

- Glick, P. (2005). Choice of Scapegoats. In J. F. Dovidio, P. Glick, & L. Rudman (Eds.), On the Nature of Prejudice: Fifty Years after Allport. (pp. 244–261). Blackwell Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Gofin, R.; Avitzour, M. Traditional Versus Internet Bullying in Junior High School Students. Matern. Child Heal. J. 2012, 16, 1625–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruys, M.L.; Sackett, P.R. Investigating the Dimensionality of Counterproductive Work Behavior. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2003, 11, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurrola-Pena, G.M.; Balcazar-Nava, P.E.; del Villar, O.E.; Lozano-Razo, G.; Zavala-Rayas, J. Construction and Validation of the Contextual Victimization Questionnaire (CVCV) with Mexican Young Adults. Int. J. Emerg. Ment. Heal. Hum. Resil. 2018, 20, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallett, N.; Dickens, G.L. De-escalation: A survey of clinical staff in a secure mental health inpatient service. Int. J. Ment. Heal. Nurs. 2015, 24, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, .M.; Hogh, A.; Garde, A.H.; Persson, R. Workplace bullying and sleep difficulties: a 2-year follow-up study. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Heal. 2014, 87, 285–294. [CrossRef]

- Haynie, D.L.; Nansel, T.; Eitel, P.; Crump, A.D.; Saylor, K.; Yu, K.; Simons-Morton, B. Bullies, Victims, and Bully/Victims:. J. Early Adolesc. 2001, 21, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerde, J.A.; Hemphill, S.A. Are Bullying Perpetration and Victimization Associated with Adolescent Deliberate Self-Harm? A Meta-Analysis. Arch. Suicide Res. 2019, 23, 353–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrichsen, J. R., Betz, M., & Lisosky, J. M. (2015). Building Digital Safety for Journalism: a Survey of Selected Issues. In Unesco Series on Internet Freedom. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0023/002323/232358e.pdf.

- Hitlan, R. T., Cliffton, R. J., & DeSoto, C. M. (2006). Perceived exclusion in the workplace: The moderating effects of gender on workrelated attitudes and psychological health. North American Journal of Psychology, 8(2), 217–236.

- Hogh, A.; Hansen, M.; Mikkelsen, E.G.; Persson, R. Exposure to negative acts at work, psychological stress reactions and physiological stress response. J. Psychosom. Res. 2012, 73, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holroyd-Leduc, J.M.; Straus, S.E. #MeToo and the medical profession. Can. Med Assoc. J. 2018, 190, E972–E973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoobler, J.M.; Brass, D.J. Abusive supervision and family undermining as displaced aggression. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 1125–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, M.; Jappinen, P.; Theorell, T.; Oxenstierna, G. Workplace conflict resolution and the health of employees in the Swedish and Finnish units of an industrial company. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 63, 2218–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, J. (2013). Bullying among prisoners: Innovations in theory and research. In J. L. Ireland (Ed.), Bullying among prisoners: The need for innovation. (2nd ed., pp. 1–30). Willan. [CrossRef]

- Jacob, L.; Kostev, K. Conflicts at work are associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular disease. 2017, 15, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Juvonen, J., & Graham, S. (2016). Peer harassment in school (J. Juvonen & S. Graham (eds.); 1st ed.). The Guilford Press.

- Kacmar, K. M., & Carlson, D. S. (1997). Further validation of the perceptions of politics scale (POPS): A multiple sample investigation. Journal of Management, 23(5), 627–658. [CrossRef]

- Kaukiainen, A.; Salmivalli, C.; Björkqvist, K.; Österman, K.; Lahtinen, A.; Kostamo, A.; Lagerspetz, K. Overt and covert aggression in work settings in relation to the subjective well-being of employees. Aggress. Behav. 2001, 27, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keashly, L. Interpersonal and Systemic Aspects of Emotional Abuse at Work: The Target’s Perspective. Violence Vict. 2001, 16, 233–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.K.; Quratulain, S.; Bell, C.M. Episodic envy and counterproductive work behaviors: Is more justice always good? J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, 128–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattak, M.N.; Zolin, R.; Muhammad, N. The combined effect of perceived organizational injustice and perceived politics on deviant behaviors. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2021, 32, 62–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimaki, M.; Virtanen, M.; Vartia, M.; Elovainio, M.; Vahtera, J.; Keltikangas-Järvinen, L. Workplace bullying and the risk of cardiovascular disease and depression. Occup. Environ. Med. 2003, 60, 779–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, G., & O’Connor, M. K. (2005). Risk Assessment and Decision Making in Business and Industry: A Practical Guid (2nd ed.). Chapman and Hall/CRC. https://www.routledge.com/Risk-Assessment-and-Decision-Making-in-Business-and-Industry-A-Practical/Koller/p/book/9780367393151.

- Laumann, E., Marsden, P. V., & Prenski, D. (1983). The boundary specification problem in network analysis (applied for conference Methods in Social Network Analysis) (R. Burt & M. Minor (eds.); 1st ed.). Sage Publications, Inc. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/238338190.

- Levine, M.; Taylor, P.J.; Best, R. Third Parties, Violence, and Conflict Resolution. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 22, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leymann, H. Mobbing and Psychological Terror at Workplaces. Violence Vict. 1990, 5, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leymann, H. The content and development of mobbing at work. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 1996, 5, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutgen-Sandvik, P. Take This Job and … : Quitting and Other Forms of Resistance to Workplace Bullying. Commun. Monogr. 2006, 73, 406–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, B.; Schuler, H.; Quell, P.; Hümpfner, G. Measuring Counterproductivity: Development and Initial Validation of a German Self-Report Questionnaire. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2002, 10, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathisen, G.E.; Einarsen, S.; Mykletun, R. The occurrences and correlates of bullying and harassment in the restaurant sector. Scand. J. Psychol. 2008, 49, 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Mavandadi, V.; Bieling, P.J.; Madsen, V. Effective ingredients of verbal de-escalation: validating an English modified version of the ‘De-Escalating Aggressive Behaviour Scale’. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Heal. Nurs. 2016, 23, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayhew, C.; McCarthy, P.; Chappell, D.; Quinlan, M.; Barker, M.; Sheehan, M. Measuring the Extent of Impact from Occupational Violence and Bullying on Traumatised Workers. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 2004, 16, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Merchant, J.; A Lundell, J. Workplace Violence Intervention Research Workshop, April 5–7, 2000, Washington, DC: Background, rationale, and summary. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2001, 20, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagle, J. Twitter, cyber-violence, and the need for a critical social media literacy in teacher education: A review of the literature. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2018, 76, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namie, G., & Namie, R. (2000). Workplace bullying: The silent epidemic. Employee Rights Quarterly, 1(2), 1–12.

- Neall, A.M.; Tuckey, M.R. A methodological review of research on the antecedents and consequences of workplace harassment. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2014, 87, 225–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuman, J.H.; Baron, R.A. Workplace Violence and Workplace Aggression: Evidence Concerning Specific Forms, Potential Causes, and Preferred Targets. J. Manag. 1998, 24, 391–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.B.; Emberland, J.S.; Knardahl, S. Workplace Bullying as a Predictor of Disability Retirement. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 59, 609–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.B.; Knardahl, S. Is workplace bullying related to the personality traits of victims? A two-year prospective study. Work. Stress 2015, 29, 128–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIOSH. (2023). Occupational violence. Acessed January 10. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/violence/default.html.

- Notelaers, G.; Van der Heijden, B.; Hoel, H.; Einarsen, S. Measuring bullying at work with the short-negative acts questionnaire: identification of targets and criterion validity. Work. Stress 2019, 33, 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Connor, M.; Gutek, B.A.; Stockdale, M.; Geer, T.M.; Melançon, R. Explaining sexual harassment judgments: looking beyond gender of the rater. Law Hum. Behav. 2004, 28, 69–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paull, M.; Omari, M.; Standen, P. When is a bystander not a bystander? A typology of the roles of bystanders in workplace bullying. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2012, 50, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, J.M. Situational antecedents and outcomes of organizational politics perceptions. J. Manag. Psychol. 2003, 18, 138–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porath, C.L.; Pearson, C.M. The Cost of Bad Behavior. Organ. Dyn. 2010, 39, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porath, C.L.; Pearson, C.M. Emotional and Behavioral Responses to Workplace Incivility and the Impact of Hierarchical Status. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 42, E326–E357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Privitera, C.; Campbell, M.A.; Mpsych; Ph.D.; Forssell, R.; Coyne, I.; Farley, S.; Axtell, C.; Sprigg, C.; Best, L.; et al. Cyberbullying: The New Face of Workplace Bullying?. CyberPsychology Behav. 2009, 12, 395–400. [CrossRef]

- Quigley, E., Ruggiero, J., McEvoy, T., Hollister, S., Schwoebel, A., & Inacker, P. (2020). Addressing workplace violence and aggression in health care settings: One unit’s journey. Nurse Leader, in press.

- A Richman, J.; Rospenda, K.M.; Nawyn, S.J.; A Flaherty, J.; Fendrich, M.; Drum, M.L.; Johnson, T.P. Sexual harassment and generalized workplace abuse among university employees: prevalence and mental health correlates. Am. J. Public Heal. 1999, 89, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, J., & Abuín, M. (2003). Cuestionario de estrategias de acoso en el trabajo: El LIPT-60 (Leymann Inventory of Pychological Terrorization) en version espa- ñola [Questionnaire of etrategies of harrassment at the workplace: El LIPT-60 (Leymann Inventory of Pychological Terrorizatio. Psiquis, 24(2), 59–69. https://www.academia.edu/33980625/Cuestionario_de_estrategias_de_acoso_psicologico_Leymann_Inventory_of_Psychological_Terrorization.

- Robinson, M.A. Using multi-item psychometric scales for research and practice in human resource management. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 57, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.L.; Bennett, R.J. A Typology of Deviant Workplace Behaviors: A Multidimensional Scaling Study. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 555–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rospenda, K.M.; Richman, J.A.; Shannon, C.A. Prevalence and Mental Health Correlates of Harassment and Discrimination in the Workplace. J. Interpers. Violence 2009, 24, 819–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosta, J.; Aasland, O.G. Perceived bullying among Norwegian doctors in 1993, 2004 and 2014–2015: a study based on cross-sectional and repeated surveys. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e018161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Hernández, J.A.; López-García, C.; Llor-Esteban, B.; Galián-Muñoz, I.; Benavente-Reche, A.P. Evaluation of the users violence in primary health care: Adaptation of an instrument. Int. J. Clin. Heal. Psychol. 2016, 16, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sackett, P., & DeVore, C. (2001). Counterproductive behaviours at work. In N. Anderson, D. S. Ones, H. K. Sinangil, & C. Viswesvaran (Eds.), Handbook of industrial work and organizational psychology. Personal Psychology (1st ed., pp. 145–164). Sage Publications, Inc.

- Scholte, R., Nelen, W., De Wit, W., & Kroes, G. (2016). Sociale veiligheid in en rond scholen [Social safety in and around schools] 2010-2016 (Number december). https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/rapporten/2016/12/23/sociale-veiligheid-in-en-rond-scholen.

- Schreurs, P. J. G., G. van de Willige, J., Brosschot, .F., Graus, G. M. H., & Tellegen, B. (1993). De Utrechtse Coping Lijst (UCL): omgaan met problemen en gebeurtenissen (The Utrecht Coping List : coping with problems and events) (revised ed). Pearson.

- Shaffer, J.A.; DeGeest, D.; Li, A. Tackling the Problem of Construct Proliferation. Organ. Res. Methods 2016, 19, 80–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarlicki, D.P.; Folger, R. Retaliation in the workplace: The roles of distributive, procedural, and interactional justice. J. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 82, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sliter, K.A.; Sliter, M.T.; Withrow, S.A.; Jex, S.M. Employee adiposity and incivility: Establishing a link and identifying demographic moderators and negative consequences. J. Occup. Heal. Psychol. 2012, 17, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P. E., & Fox, S. (2005). The stressor-emotion model of Counterproductive Work Behavior. In S. Fox & P. E. Spector (Eds.), Counterproductive Work Behavior: Investigations of actors and targets. (pp. 151–174). American Psychological Association. [CrossRef]

- Spector, P. E., & Jex, S. M. (1998). Development of four self-report measures of job stressors and strain: Interpersonal conflict at work scale, organizational constraints scale, quantitative workload inventory, and physical symptoms inventory. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 3(4), 356–367. https://psycnet.apa.org/buy/1998-12418-005.

- Sprigg, C.A.; Niven, K.; Dawson, J.; Farley, S.; Armitage, C.J. Witnessing workplace bullying and employee well-being: A two-wave field study. J. Occup. Heal. Psychol. 2019, 24, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steffgen, G.; Sischka, P.; Schmidt, A.F.; Kohl, D.; Happ, C. The Luxembourg Workplace Mobbing Scale. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2019, 35, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabor, J.; Griep, Y.; Collins, R.; Mychasiuk, R. Investigating the Neurological Correlates of Workplace Deviance Using a Rodent Model of Extinction. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaki, J.; Taniguchi, T.; Hirokawa, K. Associations of Workplace Bullying and Harassment with Pain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2013, 10, 4560–4570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.P.; Burk, R. Junior nursing students' experiences of vertical violence during clinical rotations. Nurs. Outlook 2009, 57, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.J.; Carlson, D.S.; Kacmar, K.M.; Vogel, R.M. The cost of being ignored: Emotional exhaustion in the work and family domains. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurston, R.C.; Chang, Y.; Matthews, K.A.; von Känel, R.; Koenen, K. Association of Sexual Harassment and Sexual Assault With Midlife Women’s Mental and Physical Health. JAMA Intern. Med. 2019, 179, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkuil, B., Atasayi, S., & Molendijk, M. L. (2015). Workplace bullying and mental health : A meta- analysis on cross-sectional and longitudinal data. PLoS ONE, 10(8), 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Verschuren, C.M.; Tims, M.; de Lange, A.H. A Systematic Review of Negative Work Behavior: Toward an Integrated Definition. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, P.; Reis, E. Using Questionnaire Design to Fight Nonresponse Bias in Web Surveys. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2010, 28, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, D., Marmar, C., Wilson, J., & Keane, T. (1997). Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD (Guilford Press (ed.)).

- Zivnuska, S.L.; Carlson, D.S.; Carlson, J.R.; Harris, K.J.; Harris, R.B.; Valle, M. Information and communication technology incivility aggression in the workplace: Implications for work and family. Inf. Process. Manag. 2020, 57, 102222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

|

| 1 | Due to limited space in this article, subcategories and their reduction are included in a Supplementary Table Reduction Process NWBs /harms that can be requested from the author. We suffice here with 2 subcategories of the dimension Material NWB, and one subcategory of the dimension Mental harm. |

| 2 | Michelle Demaray, Psychology Department, Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, Illinois, USA, Jorge Escartin Solanelles, Department of Social Psychology, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, Kara Ng, Alliance Manchester Business School, The University of Manchester, Manchester, UK. |

| 3 | 33 Bodily harms, 18 Material damage, 107 Mental harms, 7 Social harms. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).