1. Introduction

The world is aging very rapidly due to increased life expectancy and a decline in rates of fertility. According to a recent United Nations report, it is expected that in the next three decades, the number of people aged 65 and over will double globally, shifting from 9.3% of the population in 2020 to 16% in 2050 (United Nations Department of Economic and that Social Affairs, 2020). In Saudi Arabia, people aged 65 and over will represent 18.4% of the entire population (United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia, 2014). The aging process is usually associated with various physical and psychosocial concerns (Cornwell & Waite, 2009). It is therefore crucial to investigate factors associated with life satisfaction among older adults. Being satisfied with life for an older adult implies adapting to these age-related changes, thereby maintaining a good quality of life. Given that Saudi Arabia's population is aging rapidly, there is a growing demand for psychological research focusing on older adults in this population (Karlin, Weil, and Felmban, 2016). Specifically, it would be important to identify factors that enhance the aging experience in Saudi Arabia.

The socioemotional selectivity theory postulates that the aging process provides older people with a greater awareness that one’s lifetime is limited, which motivates them to pursue goals that benefit them in the present (Carstensen, Isaacowitz, & Charles, 1999). Thus, for example, older adults would invest much of their time and energy in making and maintaining healthy social relationships with people who are meaningful to them. With such social bonds comes greater social support, which has been found to yield positive effects on subjective well-being and life satisfaction among older adults (Yeung & Fung, 2007). Other prior research has also examined the benefits of healthy social relationships for well-being in old age, as well as the relationship of gratitude with well-being. For example, Killen and Macaskill (2015) reported that expressing gratitude contributed to increases in subjective well-being in older people. Similarly, people who are grateful also perceive greater social support (You, Lee, Lee, & Kim, 2018) and enjoyment of the present (Lau & Cheng, 2011). These findings may be sensitive to cultural differences, indicating the need for research from other cultures.

Most studies have been conducted in individualistic cultures and few have been conducted in collectivistic cultures (Chen, Kee, & Chen, 2015; Robustelli & Whisman, 2018; Sun, Jiang, Chu, & Qian, 2014). People from these cultures think differently about oneself. For example, someone from an individualistic culture derive happiness from the achievement of personal goals while someone from collectivistic culture derive happiness from social harmony (Boehm, Lyubomirsky, & Sheldon, 2011; Lu & Gilmour, 2004; Triandis, Bontempo, Villareal, Asai, & Lucca, 1988; Uchida & Kitayama, 2009). Saudi Arabia belongs also to this collectivistic culture where people are not concerned with individual stands, rather group cohesion (Elamin & Alomaim, 2011). Another difference is the expression of emotions. People from individualistic cultures tend to experience ether positive or negative while people from collectivistic cultures tend to experience positive and negative emotions simultaneously (Kitayama, Markus, & Kurokawa, 2000; Schimmack, Oishi, & Diener, 2002) especially when it comes to receiving a favor. For example, a study conducted in the Japanese culture, a collectivistic culture, reported that gratitude was expressed with positive (warmth) and negative feelings (regret, indebtedness, and remorse) (Naito & Sakata, 2010). This difference in emotion expression can have an impact on the relationship between gratitude and other outcomes.

There is limited evidence of the association between gratitude and life satisfaction in older people in Saudi Arabia. One study investigated the relationship of gratitude with life satisfaction and the mediation role of perceived stress (Yildirim & Alanazi, 2018). It was found that gratitude was positively related to life satisfaction and that this relationship was fully mediated by perceived stress; however, this research studied undergraduate students. To the best of our knowledge, no study has investigated the relationship between gratitude and life satisfaction, and the mediation role of social support and enjoyment of life among older adults in Saudi Arabia. The purpose of the current study was therefore to contribute to the literature by examining the associations between these psychological variables and to disentangle the hypothesized mediating role of social support and enjoyment of life in older individuals in Saudi Arabia.

1.1. Gratitude and Life Satisfaction

Gratitude has been found to be associated with multiple positive life outcomes. Killen and Macaskill (2015) conducted a study involving a two-week intervention with the purpose of increasing gratitude in older adults. The results of their study showed that the gratitude-enhancing intervention resulted in an increased sense of well-being and happiness and a decrease in perceived stress. Similarly, it has been established that gratitude training was better at enhancing older people’s well-being than optimism training (Salces-Cubero, Ramírez-Fernández, & Ortega-Martinez, 2019). The results of this study showed that the gratitude training intervention increased not only life satisfaction but also happiness and resilience. In a study involving middle aged and older adults in the United States and Japan, a positive association between gratitude and relationship satisfaction and overall life satisfaction was found (Robustelli & Whisman, 2018). Others have argued for a reciprocal relationship. A longitudinal design study with a sample of Latin Americans by Unanue et al. (2019) reported the existence of positive reciprocal relationship between gratitude and life satisfaction, indicating that gratitude increases life satisfaction and that, in turn, life satisfaction enhances gratitude over time.

Jans-Beken et al. (2020) reviewed studies that attempted to enhance well-being via gratitude interventions. This literature review sought to better understand causal effects. It concluded that gratitude interventions moderately increased emotional, social, and psychological well-being. Another gratitude training intervention, consisting of writing gratitude letters, resulted in positive affect increases over the course of three weeks (Toepfer, Cichy, & Peters, 2012). Gratitude journaling, another type of gratitude practice, was also found to be effective in enhancing positive affect in comparison to a control group (O’Connell, O’Shea, & Gallagher, 2017). In another randomized controlled trial of 16 weeks, O’Connell, O’Shea, & Gallagher (2018) found that an Islamic secular approach for expressing gratitude enhanced happiness. Baxter, Johnson, and Bean (2012) found that, following a gratitude intervention, daily happiness was increased in a sample of people suffering from chronic back pain. In a sample of students, it was found that an 8-week gratitude intervention increased life satisfaction in comparison to a control group, although the effect seemed small (O’Connell, O’Shea, & Gallagher, 2018). A study by Rash, Matsuba, and Prkachin (2011) reported that a gratitude intervention benefited respondents with low trait gratitude in increasing life satisfaction. These studies indicate positive benefits of gratitude for individuals’ subjective well-being. However, the findings are mostly from studies conducted in the West; further research is therefore needed from other parts of the world.

Gratitude interventions were also found to enhance other psychological variables. In a sample of undergraduate students using a quasi-experimental design, Flinchbaugh, Moore, Chang, and May (2012) found that gratitude journaling training coupled with stress management training increased participants’ sense of meaning in their lives. Another randomized controlled trial claimed that gratitude journaling training resulted in an increase in optimism (Kerr, O’Donovan, & Pepping, 2015). In a two-week randomized controlled trial, Jackowska, Brown, Ronaldson, and Steptoe (2016) found that, compared to a control group, a gratitude intervention increased hedonic well-being, optimism, and sleep quality. The fulfillment of psychological needs has been also shown to benefit from gratitude interventions. For example, in a prospective study, Lee, Tong, and Sim (2015) found that gratitude predicted participants’ relatedness and autonomy. All these findings, despite the different methodologies used, highlight the positive contribution of gratitude in people’s lives. However, these studies were conducted with samples of young people, indicating the need for research in old age.

Hypothesis 1.

Gratitude will have a positive association with life satisfaction among older adults.

1.2. Social Support and enjoyment of life as mediators

Social support has long been thought to be a protective factor for well-being. A study by Li, Ji, and Chen (2014) found that various sources of social support were predictive of emotional well-being among older adults in China. Social support was also found to be associated with life satisfaction in Chinese empty nesters, but this relationship was mediated by loneliness (Cao & Lu, 2018).

Social support has also received attention as a mediating agent. For example, social support acts as a mediator between forgiveness and life satisfaction. Zhu (2015) investigated the mediation role of social support in the relationship of forgiveness and life satisfaction and found that forgiveness was related to life satisfaction through social support. Another study reported that gratitude was linked to life satisfaction through the paths of social support and self-esteem among adolescent survivors of a disaster (Zhou, Zhen, & Wu, 2019). Social support also mediated the association between gratitude and life satisfaction and between gratitude and burnout among student-athletes in the United States (Gabana, Steinfeldt, Wong, & Chung, 2017). Nevertheless, there is a lack of evidence of the mediation role of social support in the association between gratitude and life satisfaction in older adults, particularly in the aging population in Saudi Arabia.

Hypothesis 2.

Social support will mediate the relationship between gratitude and life satisfaction.

It has been argued that gratitude maximizes of enjoyment of pleasurable experiences (Emmons, 2012) and facilitates relaxation and enjoyment of life (Lau & Cheng, 2011). In turn, studies reported that enjoyment of life was associated with life satisfaction among older adults. A study from Britain engaging not less than 999 individuals aged 65 and over reported that among the activities that enhanced the quality of life of respondents, participating in hobbies and leisure activities and having enough money to enjoy life emerged as important factors (Gabriel & Bowling, 2004). Smith et al. (2019) report that, in a sample of older individuals, sexual activity was linked to enjoyment of life, which in turn increased life satisfaction. The study reported that the well-being of older adults was increased when they were sexually active. In a longitudinal study involving individuals aged 50 and over in England, it was reported that reduced life enjoyment was related to higher mortality rates (Zaninotto, Wardle, & Steptoe, 2016). These results imply the converse, namely that enjoyment of life might reduce rates of mortality in old age. Using nationally representative data, Steptoe and Wardle (2012) found that there is an association between enjoyment of life and survival in old age. They concluded that enjoyment of life can enhance subjective well-being in old age. In addition, it was found in a sample of individuals aged 60 and over that low levels of enjoyment of life in old age may be associated with future disability (Steptoe, De Oliveira, Demakakos, & Zaninotto, 2014).

With increased socio-economic growth in recent years in Saudi Arabia, there have been changes in the lifestyle of Saudi Arabians. Research is therefore needed to address how the manner in which elderly Saudi Arabians try to enjoy life contributes to their sense of life satisfaction.

Hypothesis 3.

Enjoyment of life will mediate the relationship between gratitude and life satisfaction.

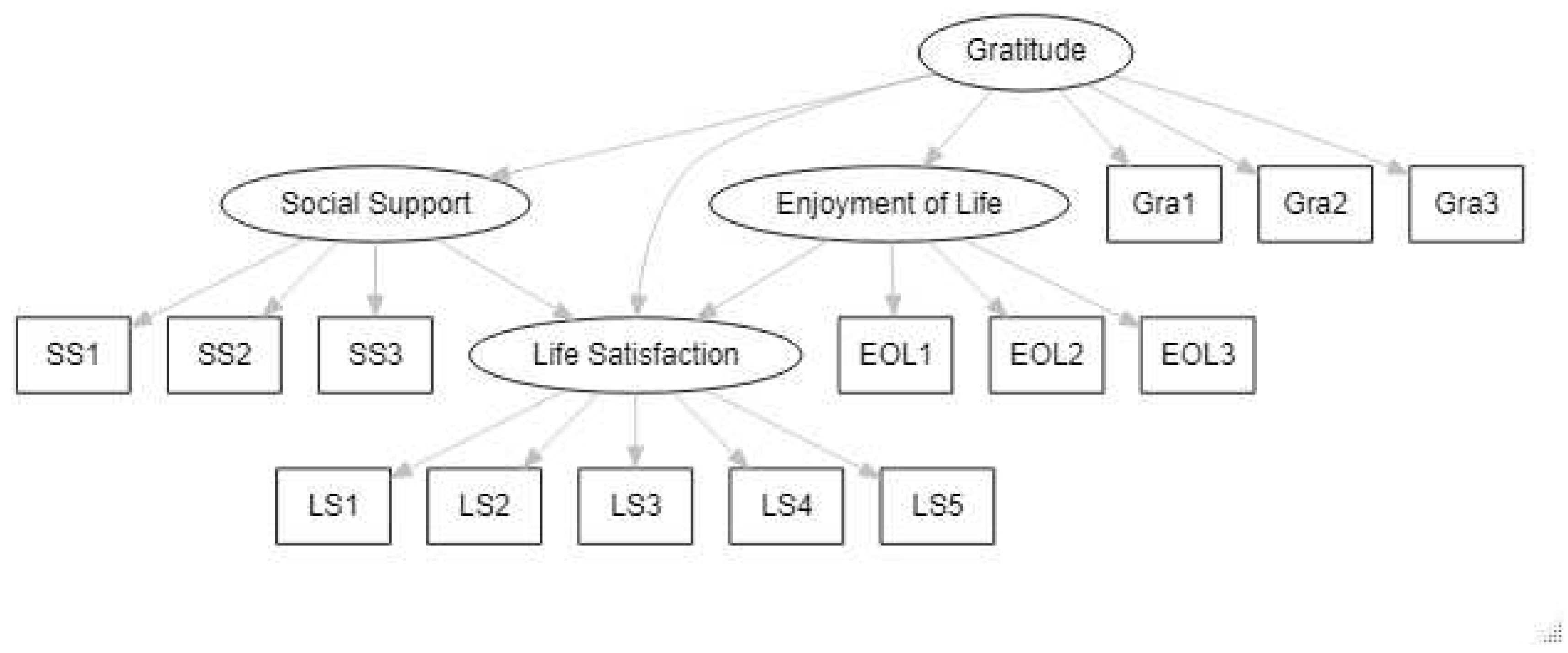

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

This cross-sectional study used a sample of older adults residing in their families aged 60 years and over. The sample was determined using convenience sampling methods. After excluding all individuals less than 60 years of age and those residing in nursing homes, a sample of 260 older individuals aged 60 to 80 was yielded. The data were collected through self-reported questionnaires. A link to the Google Forms questionnaire was sent to participants by email or on social media, including Facebook and Twitter. Among the 260 respondents, 54.6% were females and 45.5% were males, and the mean age was 65.3. The respondents were informed about the study and they provided consent to participate. The permissions to conduct this study were provided by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah.

2.2. Measures

The questionnaire consisted of several scales that have demonstrated good validity and reliability in the literature.

The Gratitude Resentment and Appreciation Test (GRAT) (Watkins, Woodward, Stone, & Kolts, 2003) was used to measure Gratitude. The GRAT consists of 44 items, with responses on a nine-point Likert scale from 1 (I strongly disagree with the statement) to 9 (I strongly agree with the statement). The scale has three subscales: sense of abundance (abbreviated Gra1 in this study), appreciation for simple pleasures (Gra2), and social appreciation (Gra3). This scale was found to have good factorial validity and internal consistency reliability (Watkins et al., 2003). The scale has been validated in Saudi Arabia (Al-Fraih, 2016). The scale demonstrated good internal consistency validity in this study (Chronbach alpha = 0.89).

The Enjoyment of Life Scale (Abdel-Aal & Mazloum, 2013) was used to measure Enjoyment of life. This scale contains 60 items recorded using a three-point Likert scale: 1 (rarely), 2 (sometimes) and 3 (always). This scale has cognitive (EOL1), affective (EOL2), and socio-behavioral subscales (EOL3). Total scores ranging between 60 and 180 were used in the analysis. This scale demonstrated an internal consistency reliability ranging between .82 and .87 (Abdel-Aal & Mazloum, 2013). In this study, the scale has an excellent Cronbach alpha’s value of 0.96.

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support Scale (MSPSS) (Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet, & Farley, 1988)was used to measure Perceived Social Support. This scale has 12 items scored on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 7 (very strongly agree) with 3 subscales: significant other subscale (SS1), family subscale (SS2), and friends subscale (SS3). The scale demonstrated good construct validity and internal reliability and test-retest reliability (Zimet et al., 1988). The scale had been adapted in Saudi Arabia (Khusaifan & El Keshky, 2017). The scale had sufficient Cronbach alpha’s value of 0.85.

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985) was used to measure Life satisfaction. This scale consists of 5 items (LS2, LS2, LS3, LS4, LS5) scored on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). This scale also exhibited high internal consistency and temporal reliability (Diener et al., 1985). The scale had been adapted in Arabic language (Abdel-Khalek & Snyder, 2007). The scale exhibited sufficient internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s value = 0.80).

A set of sample characteristics variables was also included in the questionnaire, including gender, age, marital status, employment status, living status, income, health status, and the number of children.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analyses were conducted in three phases. The first phase consisted of descriptive statistics (

Table 1 and

Table 2). The second phase consisted of mediation analysis with structural and equation models (SEM) using the ‘lavaan’ package (Rosseel, 2011). The third phase consisted of bootstrapping methods to test the mediation effect (

Table 3). The data were managed and analyzed using the R statistical software package (Ihaka & Gentleman, 1996).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics

The descriptive statistics for the variables are summarized in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

Table 1 summarizes the categorical variables and the prevalence of life satisfaction per category while

Table 2 summarizes the continuous variables and the bivariate Pearson correlation between the main variables.

3.2. Hypotheses testing

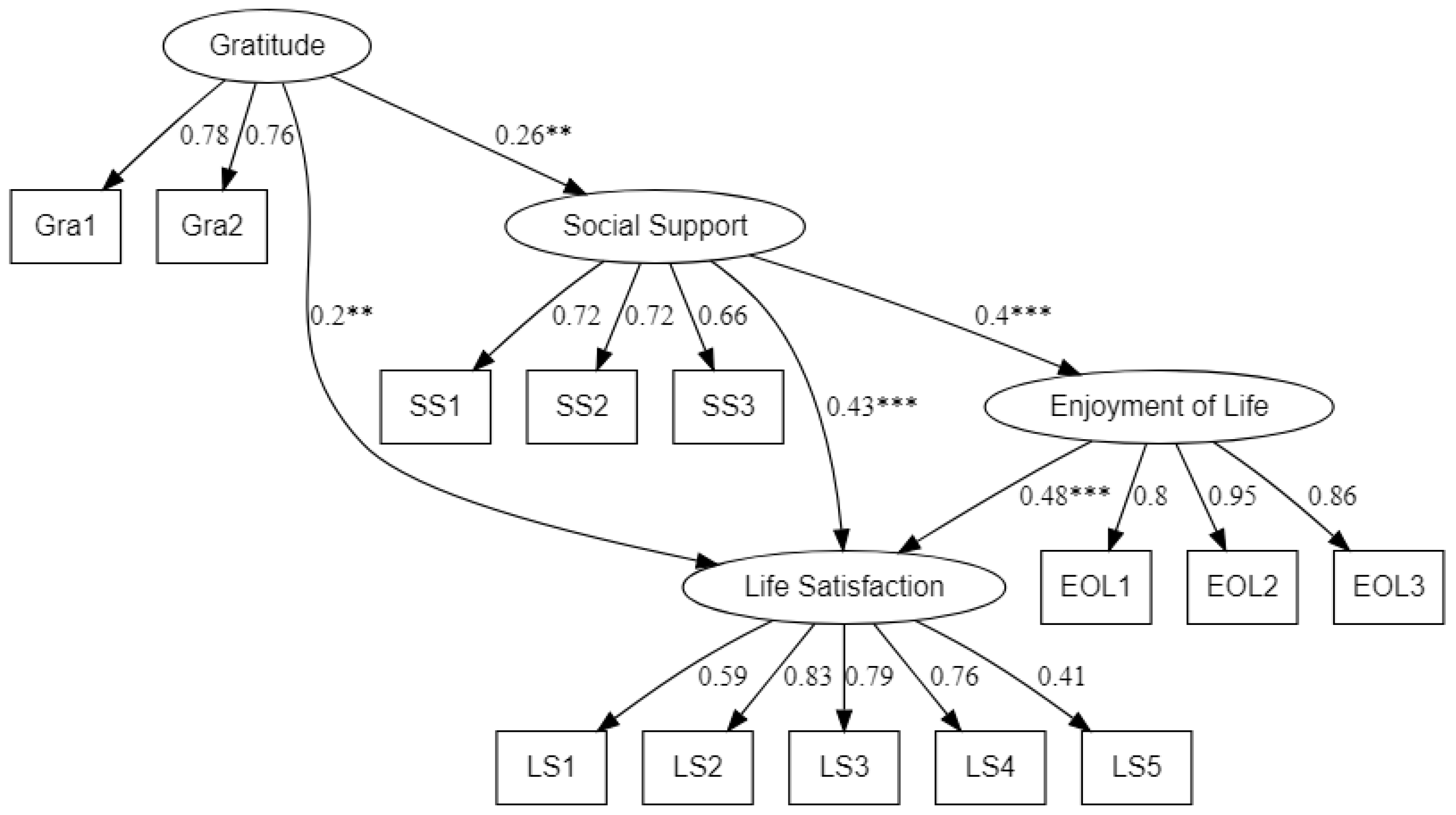

To test the hypotheses, structural equation models were employed. In the first place two models were analyzed: A fully mediated model (Model 1) in which gratitude and life satisfaction were only associated indirectly through social support and enjoyment of life. A partially mediated model (Model 2) with the indirect paths and a direct path from gratitude to life satisfaction. An ANOVA test indicated a significant chi-square difference between the two models (∆ꭓ2=79.98, p<0.001). This shows that model 2 (ꭓ2(60) = 210.04, p<0.001; RMSEA = 0.09; SRMR = 0.11; CFI = 0.90; TLI = 0.87) better fitted the data than Model 1 (ꭓ2(62) = 289.82, p<0.001; RMSEA = 0.11; SRMR = 0.18; CFI = 0.85; TLI = 0.81).

However, the social appreciation subscale poorly loaded to the gratitude scale, so it was deleted in Model 3. In addition, the path from gratitude to enjoyment of life was not significant. Therefore, in order to improve the model, this path was deleted and another path from social support to enjoyment of life was added. The results indicated that Model 3 better fitted the data (ꭓ

2(60) = 179.13,

p<0.001; RMSEA = 0.08; SRMR = 0.06; CFI = 0.92; TLI = 0.90). Thus, Model 3 was taken as the final structural model and the paths are graphed using the ‘lavaanPlot’ package (Lishinski, 2020) see

Figure 2.

The path from gratitude to life satisfaction was significant (β = 0.20,

p<0.01) and the hypothesis 1 was supported. Finally, as shown in

Table 3 and

Figure 2, Social support and enjoyment of life mediated the relationship between gratitude and life satisfaction. Although enjoyment of life mediated the relationship between gratitude and life satisfaction only via social support, hypotheses 2 and 3 were supported.

4. Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to examine the association between gratitude and life satisfaction, and to test the hypothesized mediation role of social support and enjoyment of life in the said relationship in a sample of older adults in Saudi Arabia. The results showed that gratitude was related to life satisfaction of older individuals. This means that those who expressed greater gratitude reported increased satisfaction of life beyond the contributions of confounding variables. This corroborates prior studies that have found similar trends in older individuals (Killen & Macaskill, 2015; Gabriel & Bowling, 2004).

Gratitude benefits life satisfaction through several mechanisms. Wood, Maltby, Stewart, and Joseph (2008) postulated that individuals with increased levels of gratitude perceive help as costly, valuable and altruistic. They concluded that, unlike ungrateful people, grateful people view help as beneficial for them and consequently appreciate the supportiveness of their social connections. A second mechanism may be the positive coping strategies associated with expressing gratitude. Wood, Joseph, and Linley (2007) investigated the links between gratitude and coping strategies. They claimed that people with high gratitude also avail themselves of instrumental and emotional social support. Moreover, their study concluded that grateful people were more likely to engage in active coping, planning, and positive reinterpreting of situations and were less likely to disengage and deny the existence of a problem or escape through substance use. Another explanation is that gratitude provides an antidote to stressful situations by helping people to develop resilience (Fredrickson, Tugade, Waugh, & Larkin, 2003). Expressing gratitude has also been linked to the ability to savor positive situations, which increases life satisfaction (Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2006). Finally, in times of high gratitude, negative emotions are inhibited (Lyubomksky, Sheldon, & Schkade, 2005).

The positive associations found between enjoyment of life, social support and life satisfaction are easily understandable. Enjoyment of life implies the experience of positive emotions. This is particularly important in later life in order to buffer the negative effects of age-related factors. It was found in the elderly that the more they engaged in leisure activities, the more likely they were to report high levels of subjective well-being (Mishra, 1992). Similarly, in a sample of retirees, it was reported that having fun in leisure activities was associated with increased levels of life satisfaction, and consequently with successful adaptation to retirement (Nimrod, 2007). In another study, leisure activities were found to yield health benefits thereby moderating the effects of stress (Caltabiano, 1995). Enjoyment of life was also associated with mortality rates: those who enjoyed life were more likely to live longer (Steptoe & Wardle, 2012). Social support also yields health benefits, especially in old age. A study by Penninx et al. (1997) found that high levels of social support were associated with a reduced risk of mortality (Penninx et al., 1997). In another sample of individuals aged 65 and over, it was found that social support mitigated depressive symptoms (Nizeyumukiza, Pierewan, Ndayambaje, & Ayriza, 2021; Pimentel, Afonso, & Pereira, 2012), thereby enhancing subjective well-being. All these findings explain the positive relationship found between enjoyment of life, social support and life satisfaction in old age.

This study found that social support mediated the relationship between gratitude and life satisfaction among older adults. These results corroborate those of prior studies that found similar patterns in young individuals (Gabana et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2019; Zhu, 2015). This study provides external validity for prior studies by revealing this association in a sample of older adults and from another culture. Enjoyment of life failed to mediate directly the relationship between gratitude and life satisfaction as the path from gratitude to enjoyment of life was not significant. The mechanisms underlying this finding are to be found in the cultural patterns of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Arabia being a collectivistic culture, it is possible that expressing gratitude may be accompanied by both positive and negative emotions such as regret, indebtedness, and remorse as it was found in collectivistic cultures (Kimura, 1994; Washizu & Naito, 2015). This may explain why expressing gratitude may not directly lead to feelings of enjoyment, but it seems that it does so through social support. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first that examined the sequential mediation pathway from gratitude to social support, to enjoyment of life and then to life satisfaction among older adults.

Despite the implications of this study, there are some limitations that must be acknowledged. First, the design of the study was cross-sectional. Therefore, no causal effects can be assumed. Future research should use longitudinal designs in order to determine causality. Second, the data were collected via self-reported questionnaires. Future research should use other methods of data collection, including interviews, peer reports and behavior observation. Third, the study used convenience sampling methods which are not ideal for generalizability of the findings. Future research should use random sampling.

5. Conclusions

This study presents a picture of the relationships between gratitude and life satisfaction, and the mediation role of social support and enjoyment of life in older individuals in Saudi Arabia. The main findings revealed a positive association between gratitude and life satisfaction. Moreover, a mediation role of social support and enjoyment of life was revealed in a serial pathway model. These findings are relevant to elderly individuals, to health care systems, and to the field of geriatrics in general. Efforts to enhance gratitude, social support, and enjoyment in old age can increase life satisfaction, which might contribute to successful aging. For practitioners, these findings can inform which interventions should be used to promote the life satisfaction of older adults in a country that is expected to have an increased number of older adults. For future research, it is important to address these associations using longitudinal designs in order to obtain additional insights. Moreover, randomized controlled trials among older adults in Saudi Arabia might yield better insights than observational studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Mogeda El Keshky; Data curation, Mogeda El Keshky; Formal analysis, Mogeda El Keshky and Feng Kong; Funding acquisition, Shatha Khusaifan; Investigation, Mogeda El Keshky and Shatha Khusaifan; Methodology, Mogeda El Keshky and Shatha Khusaifan; Project administration, Shatha Khusaifan; Writing – original draft, Mogeda El Keshky and Shatha Khusaifan; Writing – review & editing, Mogeda El Keshky, Shatha Khusaifan and Feng Kong.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the institutional review board of the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) of King Abdulaziz University in Saudi Arabia.

Informed Consent Statement

All subjects were informed about the study and all provided informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR), at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia under grant no.(KEP: 12-246-39).The author, therefore, acknowledge with thanks to DSR for their technical and financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

References

- Abdel-Khalek, A. , & Snyder, C. R. (2007). Correlates and predictors of an Arabic translation of the Snyder Hope Scale. R. ( 2(4), 228–235. [CrossRef]

- AbdelAal, T. , & Mazloum, R. (2013). Enjoy Life in Relation to Some Positive Personality Variables “A Study in Positive Psychology.” Journal of the Faculty of Education, Banha, 2(93), 79-165.

- Al-Fraih, A. H. (2016). Psychometric properties of the Gratitude Scale on a samle of genderal education teachers in Makkah.

- Boehm, J. K. , Lyubomirsky, S., & Sheldon, K. M. (2011). A longitudinal experimental study comparing the effectiveness of happiness-enhancing strategies in Anglo Americans and Asian Americans. Cognition and Emotion, 1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caltabiano, M. L. (1995). Main and Stress-Moderating Health Benefits of Leisure. Loisir et Société / Society and Leisure. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q. , & Lu, B. (2018). Mediating and moderating effects of loneliness between social support and life satisfaction among empty nesters in China. ( 2018). Mediating and moderating effects of loneliness between social support and life satisfaction among empty nesters in China. Current Psychology, 2. [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L. L. , Isaacowitz, D. M., & Charles, S. T. (1999). Taking Time Seriously: A Theory of Socioemotional Selectivity. American Psychologist. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L. H. , Kee, Y. H., & Chen, M. Y. (2015). Why Grateful Adolescent Athletes are More Satisfied with their Life: The Mediating Role of Perceived Team Cohesion. Social Indicators Research. [CrossRef]

- Cornwell, E. Y. , & Waite, L. J. (2009). Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. J. ( 50(1), 31–48. [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. , Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction With Life Scale. ( 49(1), 71–75. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elamin, A. , & Alomaim, N. (2011). Does Organizational Justice Influence Job Satisfaction and Self-Perceived Performance in Saudi Arabia Work Environment? International Management Review.

- Emmons, R. A. (2012). Queen of the Virtues? Gratitude as Human Strength. Reflective Practice: Formation and Supervision in Ministry.

- Flinchbaugh, C. L. , Moore, E. W. G., Chang, Y. K., & May, D. R. (2012). Student Well-Being Interventions: The Effects of Stress Management Techniques and Gratitude Journaling in the Management Education Classroom. Journal of Management Education. [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L. , Tugade, M. M., Waugh, C. E., & Larkin, G. R. (2003). What Good Are Positive Emotions in Crises? A Prospective Study of Resilience and Emotions Following the Terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11th, 2001. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 11 September. [CrossRef]

- Gabana, N. T. , Steinfeldt, J. A., Wong, Y. J., & Chung, Y. B. (2017). Gratitude, burnout, and sport satisfaction among college student-athletes: The mediating role of perceived social support. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, Z. , & Bowling, A. N. N. (2004). N. N. ( 2004). Quality of life from the perspectives of older people. (Ziller 1974), 675–691. [CrossRef]

- Ihaka, R. , & Gentleman, R. (1996). R: A Language for Data Analysis and Graphics. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. [CrossRef]

- Jackowska, M. , Brown, J., Ronaldson, A., & Steptoe, A. (2016). The impact of a brief gratitude intervention on subjective well-being, biology and sleep. Journal of Health Psychology, 2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlin, N. J. , Weil, J., & Felmban, W. (2016). Aging in Saudi Arabia. ( 2, 233372141562391. [CrossRef]

- Kerr, S. L. , O’Donovan, A., & Pepping, C. A. (2015). Can Gratitude and Kindness Interventions Enhance Well-Being in a Clinical Sample? Journal of Happiness Studies. [CrossRef]

- Khusaifan, S. J. , & El Keshky, M. E. S. (2017). Social support as a mediator variable of the relationship between depression and life satisfaction in a sample of Saudi caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. International Psychogeriatrics. [CrossRef]

- Killen, A. , & Macaskill, A. (2015). Using a Gratitude Intervention to Enhance Well-Being in Older Adults. Journal of Happiness Studies. [CrossRef]

- Kimura, K. (1994). The Multiple Functions of <em>Sumimasen</em>. Issues in Applied Linguistics. [CrossRef]

- Kitayama, S. , Markus, H. R., & Kurokawa, M. (2000). Culture, emotion, and well-being: Good feelings in Japan and the United States. Cognition and Emotion. [CrossRef]

- Lau, R. W. L. , & Cheng, S. T. (2011). Gratitude lessens death anxiety. T. ( 8(3), 169–175. [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.-N. , Tong, E. M. W., & Sim, D. (2015). The dual upward spirals of gratitude and basic psychological needs. ( 1(2), 87–97. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H. , Ji, Y., & Chen, T. (2014). The roles of different sources of social support on emotional well-being among Chinese elderly. PLoS ONE. [CrossRef]

- Lishinski, A. (2020). lavaanPlot 0.5.1. Retrieved , 2021, from https://www.alexlishinski. 1 December.

- Lu, L. , & Gilmour, R. (2004). Culture and conceptions of happiness: individual oriented and social oriented swb. Journal of Happiness Studies. [CrossRef]

- Lyubomksky, S. , Sheldon, K. M., & Schkade, D. (2005). Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S. (1992). Leisure activities and life satisfaction in old age: A case study of retired government employees living in urban areas. Activities, Adaptation and Aging. [CrossRef]

- Naito, T. , & Sakata, Y. (2010). Gratitude, indebtedness, and regret on receiving a friend’s favor in Japan. Psychologia. [CrossRef]

- Nimrod, G. (2007). Retirees ’ Leisure : Activities, Benefits, and their Contribution to Life Satisfaction. Leisure Studies. [CrossRef]

- Nizeyumukiza, E. , Pierewan, A. C., Ndayambaje, E., & Ayriza, Y. (2021). Social Capital and Mental Health among Older Adults in Indonesia: A Multilevel Approach. Journal of Population and Social Studies. [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, B. H. , O’Shea, D., & Gallagher, S. (2017). Feeling Thanks and Saying Thanks: A Randomized Controlled Trial Examining If and How Socially Oriented Gratitude Journals Work. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, B. H. , O’Shea, D., & Gallagher, S. (2018). Examining Psychosocial Pathways Underlying Gratitude Interventions: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Happiness Studies, 2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penninx, B. W. J. H. , Van Tilburg, T., Kriegsman, D. M. W., Deeg, D. J. H., Boeke, A. J. P., & Van Eijk, J. T. M. (1997). Effects of social support and personal coping resources on mortality in older age: The longitudinal aging study Amsterdam. American Journal of Epidemiology. [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, A. F. , Afonso, R. M., & Pereira, H. (2012). Depression and Social Support in Old Age. Psicologia, Saúde e Doenças, /: Retrieved from http, 3622. [Google Scholar]

- Rash, J. A. , Matsuba, M. K., & Prkachin, K. M. (2011). Gratitude and well-being: Who benefits the most from a gratitude intervention? Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being. [CrossRef]

- Robustelli, B. L. , & Whisman, M. A. (2018). Gratitude and Life Satisfaction in the United States and Japan. A. ( 19(1), 41–55. [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. (2011). lavaan : an R package for structural equation modeling and more Version 0. 5-10 ( BETA ), /: from http.

- Salces-cubero, I. M. , Ramírez-fernández, E., Raquel, A., Mar, I., & Ortega-mart, A. R. (2019). Strengths in older adults : differential effect of savoring, gratitude and optimism on well-being. Aging & Mental Health. [CrossRef]

- Schimmack, U. , Oishi, S., & Diener, E. (2002). Cultural influences on the relation between pleasant emotions and unpleasant emotions: Asian dialectic philosophies or individualism-collectivism? Cognition and Emotion. [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, K. M. , & Lyubomirsky, S. (2006). How to increase and sustain positive emotion: The effects of expressing gratitude and visualizing best possible selves. Journal of Positive Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Smith, L. , Yang, L., Veronese, N., Soysal, P., Stubbs, B., & Jackson, S. E. (2019). Sexual Activity is Associated with Greater Enjoyment of Life in Older Adults. E. ( 7(1), 11–18. [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, A. , De Oliveira, C., Demakakos, P., & Zaninotto, P. (2014). Enjoyment of life and declining physical function at older ages: A longitudinal cohort study. Cmaj. [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, A. , & Wardle, J. (2012). Enjoying Life and Living Longer. ( 172(3), 273–275. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, P. , Jiang, H., Chu, M., & Qian, F. (2014). Gratitude and school well-being among Chinese university students: Interpersonal relationships and social support as mediators. Social Behavior and Personality, 1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toepfer, S. M. , Cichy, K., & Peters, P. (2012). Letters of Gratitude: Further Evidence for Author Benefits. Journal of Happiness Studies. [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H. C. , Bontempo, R., Villareal, M. J., Asai, M., & Lucca, N. (1988). Individualism and collectivism. Cross-cultural perspectives on self-ingroup relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Uchida, Y. , & Kitayama, S. (2009). Happiness and unhappiness in East and West: Themes and variations. Emotion. [CrossRef]

- Unanue, W. , Gomez Mella, M. E., Cortez, D. A., Bravo, D., Araya-Véliz, C., Unanue, J., & Van Den Broeck, A. (2019). The Reciprocal Relationship Between Gratitude and Life Satisfaction: Evidence From Two Longitudinal Field Studies. Frontiers in Psychology. [CrossRef]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, P. D. 53. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, P. D. (2020). World Population Ageing 2020 Highlights: Living arrangements of older persons (ST/ESA/SER.A/451), /: https.

- United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia, U. N. 54. United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia, U. N. (2014). The demographic profile of Saudi Arabia, /: http.

- Washizu, N. , & Naito, T. (2015). The Emotions Sumanai, Gratitude, and Indebtedness, and Their Relations to Interpersonal Orientation and Psychological Well-Being Among Japanese University Students. International Perspectives in Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Watkins, P. C. , Woodward, K., Stone, T., & Kolts, R. L. (2003). Gratitude and happiness: Development of a measure of gratitude, and relationships with subjective well-being. Social Behavior and Personality. [CrossRef]

- Wood, A. M. , Joseph, S., & Linley, P. A. (2007). Coping style as a psychological resource of grateful people. A. ( 26(9), 1076–1093. [CrossRef]

- Wood, A. M. , Maltby, J., Stewart, N., & Joseph, S. (2008). Conceptualizing gratitude and appreciation as a unitary personality trait. ( 44(3), 621–632. [CrossRef]

- Yeung, G. T. Y. , & Fung, H. H. (2007). Social support and life satisfaction among Hong Kong Chinese older adults: Family first? European Journal of Ageing. [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, M. , & Alanazi, Z. (2018). Gratitude and Life Satisfaction: Mediating Role of Perceived Stress. International Journal of Psychological Studies. [CrossRef]

- You, S. , Lee, J., Lee, Y., & Kim, E. (2018). Gratitude and life satisfaction in early adolescence: The mediating role of social support and emotional difficulties. Personality and Individual Differences, 20 December. [CrossRef]

- Zaninotto, P. , Wardle, J., & Steptoe, A. (2016). Sustained enjoyment of life and mortality at older ages: Analysis of the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. BMJ (Online). [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X. , Zhen, R., & Wu, X. (2019). Understanding the Relation between Gratitude and Life Satisfaction among Adolescents in a Post-Disaster Context: Mediating Roles of Social Support, Self-Esteem, and Hope. Child Indicators Research, 1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H. (2015). Social Support and Affect Balance Mediate the Association Between Forgiveness and Life Satisfaction. Social Indicators Research. [CrossRef]

- Zimet, G. D. , Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. K. ( 52(1), 30–41. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).