Submitted:

26 May 2023

Posted:

26 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Material and Measures

2.2.1. Video Games

2.2.2. Aggressive Cognition

2.2.3. Aggressive Behavior

2.2.4. Trait Aggression

2.2.5. Video Game Exposure

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Electrophysiological Recording and Data Processing

3. Results

3.1. Manipulation Check

| Dimension | Solo mode M(SD) |

Competitive mode M(SD) |

t(33) | p | 95% CI for mean difference |

d | 95% CI for d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggressive content | 1.75 (0.93) | 1.68 (0.95) | 0.21 | .84 | [-0.58, 0.71] | 0.07 | [-0.60, 0.74] |

| Prosocial content | 2.06 (1.12) | 2.26 (0.93) | -0.58 | .57 | [-0.91, 0.51] | -0.20 | [-0.86, 0.47] |

| Competition | 2.94 (1.06) | 4.05 (0.71) | -3.71 | < .001 | [-1.73, -0.50] | -1.26 | [-1.98, -0.52] |

| Actions | 3.94 (0.77) | 3.90 (0.99) | 0.14 | .89 | [-0.58, 0.66] | 0.05 | [-0.62, 0.71] |

| Enjoyment | 2.94 (1.18) | 3.37 (0.83) | -1.26 | .22 | [-1.13, 0.26] | -0.43 | [-1.10, 0.25] |

| Excitement | 3.31 (0.95) | 3.53 (0.91) | -0.68 | .50 | [-0.85, 0.42] | -0.23 | [-0.90, 0.44] |

| Difficulty | 2.94 (1.06) | 3.42 (1.12) | -1.30 | .20 | [-1.24, 0.27] | -0.44 | [-1.11, 0.24] |

3.2. Behavioural Data

3.2.1. Oddball Paradigm

3.2.2. Hot Sauce

3.3. ERP Results

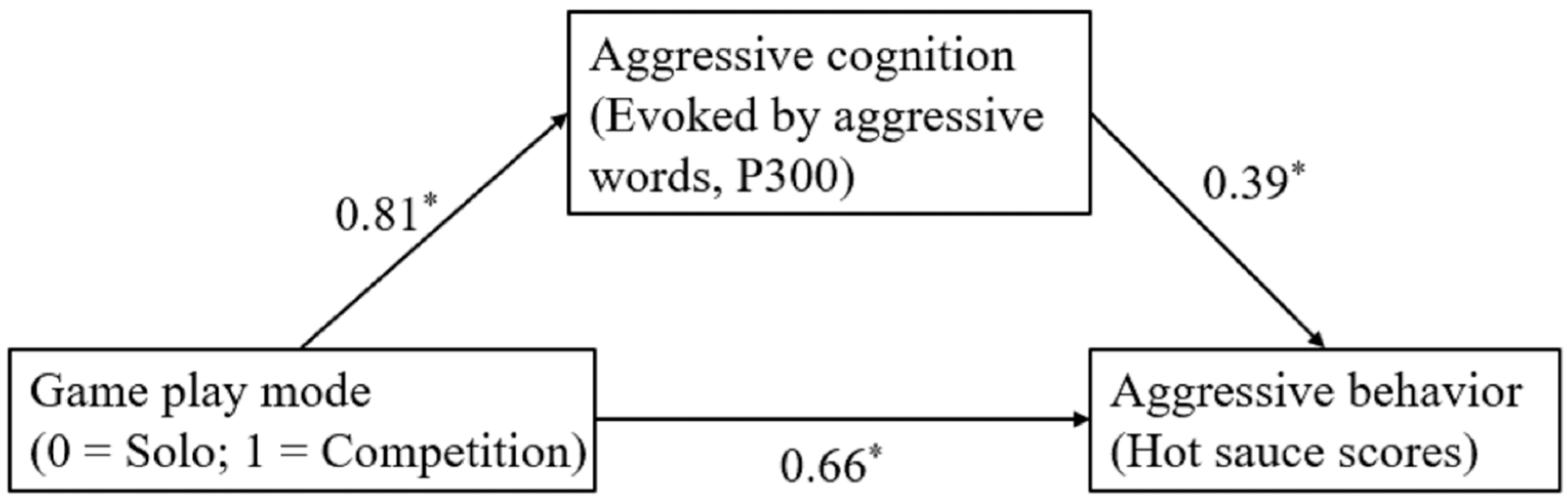

3.4. Mediation Model Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Newzoo. 2022 Global games market report. Available online: https://newzoo.com/cn/articles/the-games-market-will-show-strong-resilence-in-2022-cn (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Greitemeyer, T.; Mügge, D.O. Video games do affect social outcomes: A meta-analytic review of the effects of violent and prosocial video game play. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 40, 578–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, C.A.; Shibuya, A.; Ihori, N.; Swing, E.L.; Bushman, B.J.; Sakamoto, A.; Rothstein, H.R.; Saleem, M. Violent video game effects on aggression, empathy, and prosocial behavior in eastern and western countries: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 136, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greitemeyer, T. The contagious impact of playing violent video games on aggression: Longitudinal evidence. Aggressive Behav. 2019, 45, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Z.; Nie, Q.; Zhu, Z.G.; Guo, C. Violent video game exposure and (Cyber)bullying perpetration among Chinese youth: The moderating role of trait aggression and moral identity. Comput. Human Behav. 2020, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Z.; Nie, Q.; Guo, C.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Bushman, B.J. A longitudinal study of link between exposure to violent video games and aggression in Chinese adolescents: The mediating role of moral disengagement. Dev. Psychol. 2019, 55, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, Z.; Yang, C.Y.; Stomski, M.; Nie, Q.; Guo, C. Violent video game exposure and bullying in early adolescence: A longitudinal study examining moderation of trait aggressiveness and moral identity. Psychol. Violence 2022, 12, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, J.; Gao, X. Violent video games exposure and aggression: The role of moral disengagement, anger, hostility, and disinhibition. Aggressive Behav. 2019, 45, 662–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bushman, B.J. Violent media and hostile appraisals: A meta-analytic review. Aggressive Behav. 2016, 42, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Ferguson, C.J. Competitively versus cooperatively? An analysis of the effect of game play on levels of stress. Comput. Human Behav. 2016, 56, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, P.J.C.; Willoughby, T. The effect of video game competition and violence on aggressive behavior: Which characteristic has the greatest influence? Psychol. Violence 2011, 1, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, P.J.C.; Willoughby, T. The effect of violent video games on aggression: Is it more than just the violence? Aggress. Violent Behav. 2011, 16, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowsett, A.; Jackson, M. The effect of violence and competition within video games on aggression. Comput. Human Behav. 2019, 99, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawk, C.E.; Ridge, R.D. Is it only the violence? The effects of violent video game content, difficulty, and competition on aggressive behavior. J. Media Psychol. 2021, 33, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newzoo. 2021 Global Esports & Live Streaming Market Report. Available online: https://newzoo.com/insights/trend-reports/newzoos-global-esports-live-streaming-market-report-2021-free-version (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- Gough, C. eSports Market Revenue Worldwide from 2018 to 2023, 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/490522/global-esports-market-revenue/ (accessed on 22 September 2022).

- Deutsch, M. Cooperation and competition. In Conflict, interdependence, and justice, Coleman, P.T., Ed.; Springer: New York, 2011; pp. 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, C.A.; Bushman, B.J. Human aggression. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2002, 53, 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.A.; Bushman, B.J. Media violence and the general aggression model. J. Soc. Issues 2018, 74, 386–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.A.; Morrow, M. Competitive aggression without interaction: Effects of competitive versus cooperative instructions on aggressive behavior on video games. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 21, 1020–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, P.J.C.; Willoughby, T. Demolishing the competition: The longitudinal link between competitive video games, competitive gambling, and aggression. J. Youth Adolesc. 2013, 42, 1090–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, P.J.C.; Willoughby, T. The longitudinal association between competitive video game play and aggression among adolescents and young Adults. Child Dev. 2016, 87, 1877–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddell, J.C.; Peng, W. Does it matter with whom you slay? The effects of competition, cooperation and relationship type among video game players. Comput. Human Behav. 2014, 38, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastin, M.S.; Griffiths, R.P. Unreal: Hostile expectations from social gameplay. New Media Soc. 2009, 11, 509–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, C.; Wang, L.; Piao, Q. Effects of violent and non-violent computer video games on explicit and implicit aggression. J. Softw. 2010, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmierbach, M. “Killing Spree”: Exploring the connection between competitive game play and aggressive cognition. Commun. Res. 2010, 37, 256–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuer, J.; Scharkow, M.; Quandt, T. Sore losers? A reexamination of the frustration–aggression hypothesis for colocated video game play. Psychol. Pop. Media Cult. 2013, 4, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastin, M.S. The influence of competitive and cooperative group game play on state hostility. Hum. Commun. Res. 2007, 33, 450–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihan, R.; Anisimowicz, Y.; Nicki, R. Safer with a partner: Exploring the emotional consequences of multiplayer video gaming. Comput. Human Behav. 2015, 44, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Cao, Y.; Tian, J. Effects of violent video games on players’ and observers’ aggressive cognitions and aggressive behaviors. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2021, 203, 105005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnagey, N.L.; Anderson, C.A. The effects of reward and punishment in violent video games on aggressive affect, cognition, and behavior. Psychol. Sci. 2005, 16, 882–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluemke, M.; Zumbach, J. Assessing aggressiveness via reaction times online. Cyberpsychology 2012, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velez, J.A.; Greitemeyer, T.; Whitaker, J.L.; Ewoldsen, D.R.; Bushman, B.J. Violent video games and reciprocity: The attenuating effects of cooperative game play on subsequent aggression. Commun. Res. 2014, 43, 447–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridge, R.D.; Hawk, C.E.; McCombs, L.D.; Richards, K.J.; Schultz, C.A.; Ashton, R.K.; Hartvigsen, L.D.; Bartlett, D. ’It doesn’t affect me!’—Do immunity beliefs prevent subsequent aggression after playing a violent video game? J. Media Psychol. 2023, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Gao, J. Effects of same-sex avatar versus opposite-sex avatar violent video games on aggressive behavior among Chinese children. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2022, 31, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, C.J.; Rueda, S.M. Examining the validity of the modified Taylor competitive reaction time test of aggression. J. Exp. Criminol. 2009, 5, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, C.J.; Smith, S.; Miller-Stratton, H.; Fritz, S.; Heinrich, E. Aggression in the laboratory: Problems with the validity of the modified Taylor Competitive Reaction Time Test as a measure of aggression in media violence studies. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2008, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, J.D.; Soloman, S.; Greenberg, J.; McGregor, H.A. A hot new way to measure aggression: Hot sauce allocation. Aggressive Behav. 1999, 25, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segalowitz, S.J.; Davies, P.L. Charting the maturation of the frontal lobe: An electrophysiological strategy. Brain Cogn. 2004, 55, 116–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu Loke, I.; Evans, A.D.; Lee, K. The neural correlates of reasoning about prosocial-helping decisions: an event-related brain potentials study. Brain Res. 2011, 1369, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholow, B.D.; Bushman, B.J.; Sestir, M.A. Chronic violent video game exposure and desensitization to violence: Behavioral and event-related brain potential data. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 42, 532–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelhardt, C.R.; Bartholow, B.D.; Kerr, G.T.; Bushman, B.J. This is your brain on violent video games: Neural desensitization to violence predicts increased aggression following violent video game exposure. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 47, 1033–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staude-Müller, F.; Bliesener, T.; Luthman, S. Hostile and hardened? An experimental study on (de-)sensitization to violence and suffering through playing video games. Swiss J. Psychol. 2008, 67, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Teng, Z.; Lan, H.; Xin, Z.; Yao, D. Short-term effects of prosocial video games on aggression: An event-related potential study. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohseni, M.R.; Liebold, B.; Pietschmann, D. Extensive modding for experimental game research. In Game research methods; Lankoski, P., Björk, S., Eds.; ETC Press, 2015; Volume 340. [Google Scholar]

- McClintock, C.G.; Nuttin, J.M. Development of competitive game behavior in children across two cultures. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1969, 5, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.A.; Dill, K.E. Violent video games and aggressive thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 78, 772–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, P.J.C. Demolishing the competition: The association between competitive video game play and aggression among adolescents and young adults. Brock University, St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada, 2015.

- Buss, A.H.; Perry, M. The Aggression Questionnaire. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 63, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartholow, B.D.; Sestir, M.A.; Davis, E.B. Correlates and consequences of exposure to video game violence: Hostile personality, empathy, and aggressive behavior. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2005, 31, 1573–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fikkers, K.M.; Piotrowski, J.T.; Valkenburg, P.M. Assessing the reliability and validity of television and game violence exposure measures. Commun. Res. 2017, 44, 117–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Z.; Nie, Q.; Guo, C.; Liu, Y. Violent video game exposure and moral disengagement in early adolescence: The moderating effect of moral identity. Comput. Human Behav. 2017, 77, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Linking violent video games to cyberaggression among college students: A cross-sectional study. Aggressive Behav. 2022, 48, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delorme, A.; Makeig, S. EEGLAB: an open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics including independent component analysis. J. Neurosci. Methods 2004, 134, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach; Guilford Press, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonta, B. Cooperation and competition in peaceful societies. Psychol. Bull. 1997, 121, 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclin, E.L.; Mathewson, K.E.; Low, K.A.; Boot, W.R.; Kramer, A.F.; Fabiani, M.; Gratton, G. Learning to multitask: Effects of video game practice on electrophysiological indices of attention and resource allocation. Psychophysiology 2011, 48, 1173–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terkildsen, T.; Makransky, G. Measuring presence in video games: An investigation of the potential use of physiological measures as indicators of presence. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2019, 126, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, S.; Guo, K.; Li, W.; Yan, Y.; Zhou, L. Short-term exposure to violent media games leads to sensitization to violence: An ERP research. Studies of Psychology and Behavior 2013, 11, 732–738. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, K.E.; Anderson, C.A. A theoretical model of the effects and consequences of playing video games. In Playing Video Games Motives Responses And Consequences, Vorderer, P., Bryant, J., Eds.; Mahwah, N J : Lawrence Erlbaum: 2006; pp. 363-378.

- Ferguson, C.J. Violent video games and the Supreme Court: lessons for the scientific community in the wake of Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association. Am. Psychol. 2013, 68, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, R.B.; Clippinger, C.A. Aggression, competition and computer games: Computer and human opponents. Comput. Human Behav. 2002, 18, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, J.D.; Drummond, A.; Nova, N. Violent Video Games: The Effects of Narrative Context and Reward Structure on In-Game and Postgame Aggression. J. Exp. Psychol.-Appl. 2015, 21, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.; Jing, Y.Y.; Liu, R.D.; Ding, Y.; Wang, J. Wean your child off video games: Using external rewards to undermine intrinsic motivation to play interesting video games. Curr. Psychol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobel, A.; Engels, R.; Stone, L.L.; Burk, W.J.; Granic, I. Video gaming and children’s psychosocial wellbeing: A longitudinal study. J. Youth Adolesc. 2017, 46, 884–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).