Submitted:

25 May 2023

Posted:

26 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Edinburg Postnatal Depression Scale

2.2. Experiences in Close Relationship Scale

2.3. Coping Orientation for problem Experiences

3. Results

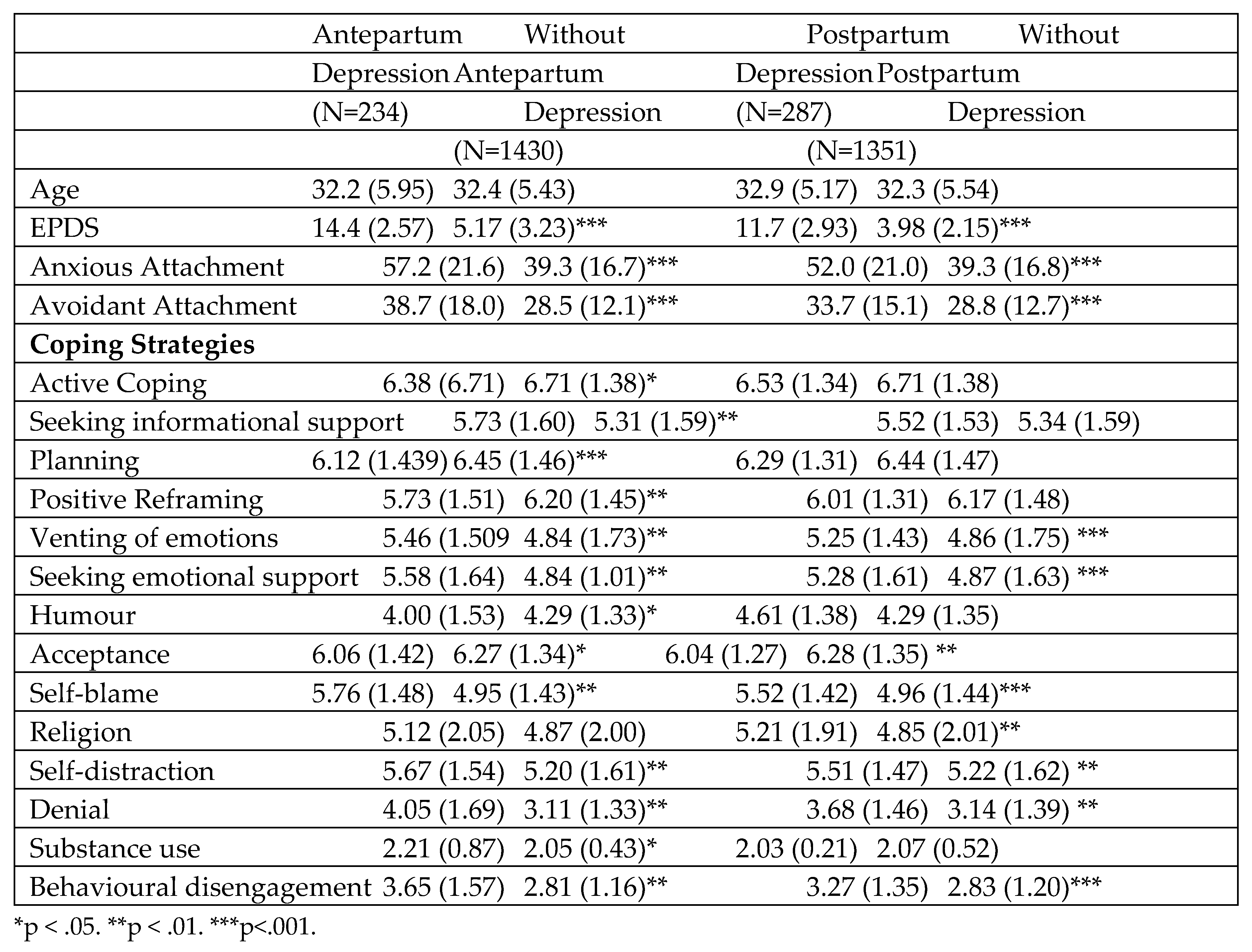

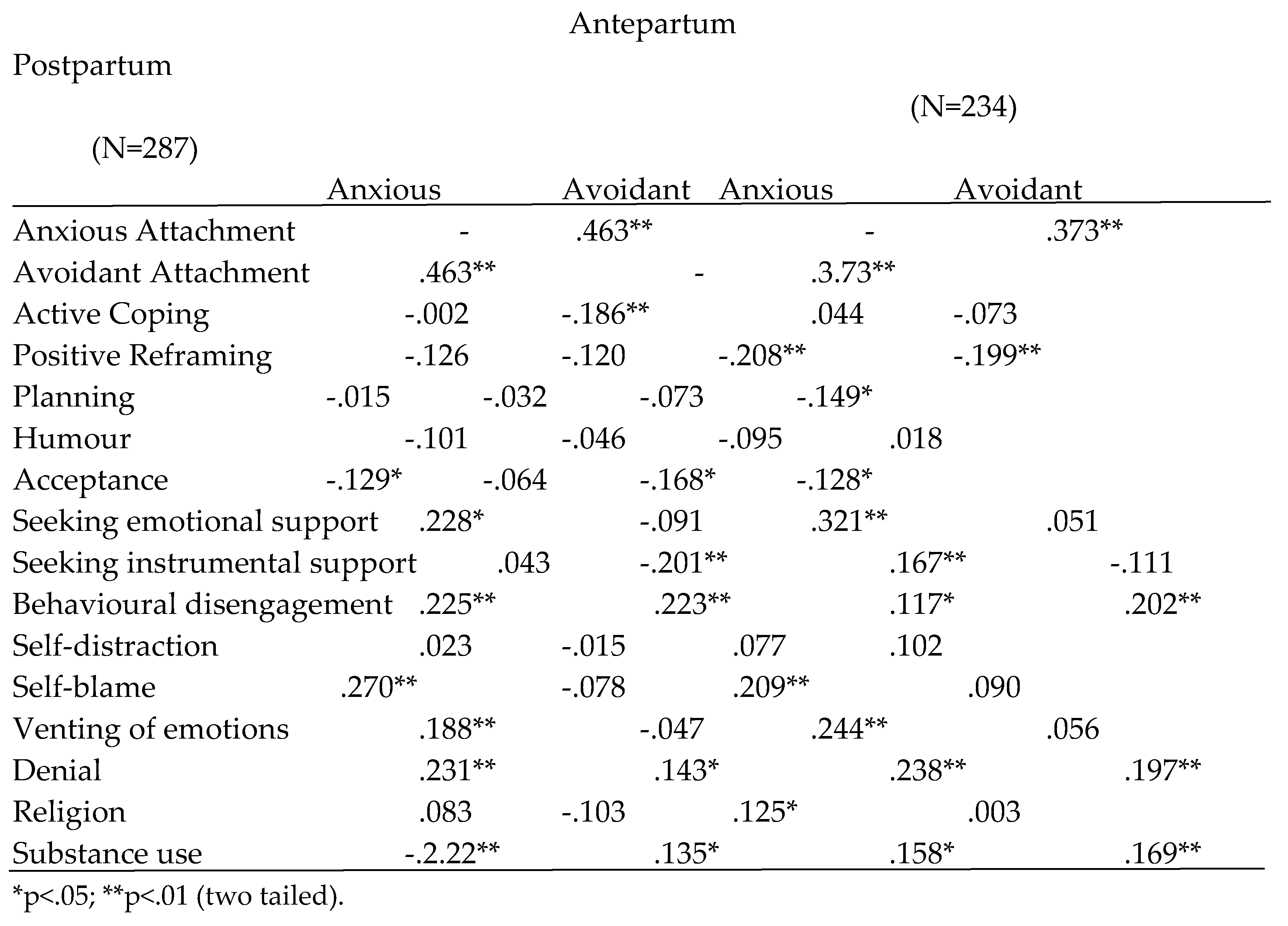

3.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.3. SEM Analysis

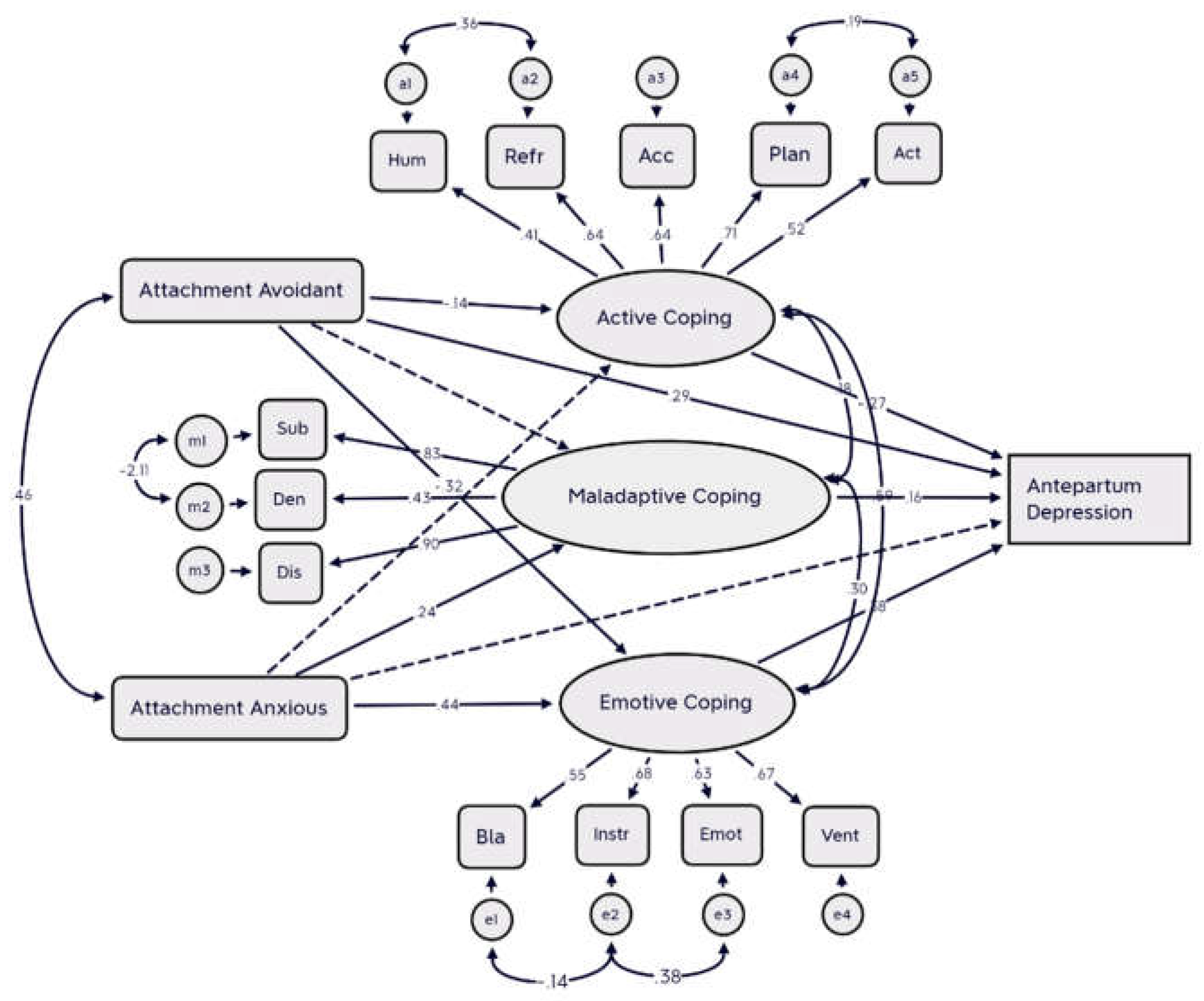

3.3.1. SEM Antepartum Depression

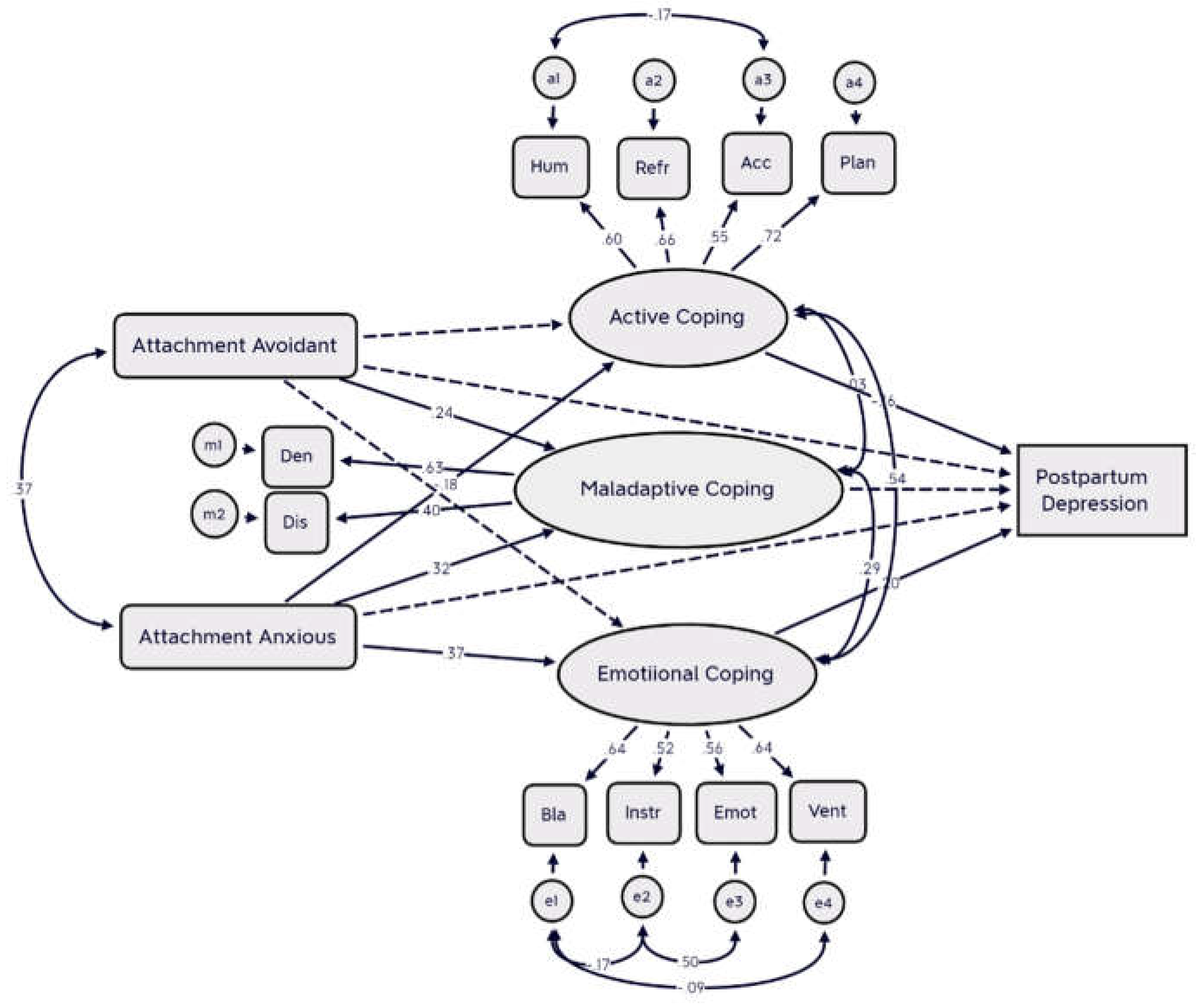

3.3.2. SEM Postpartum Depression

4. Discussion

5. Antepartum Depression

6. Postpartum Depression

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gavin, I.N. , Gaynes N.B, Lohr N.K, Meltzer-Brody S., Gartlehner G, Swinson T. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2005; 106 (5 Part 1):1071-83. [CrossRef]

- Langan, R.; Goodbred, A.J. Identification and Management of Peripartum Depression. American family physician 2016, 93, 852–8. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Zotes, A.; Labad, J.; Martín-Santos, R.; García-Esteve, L.; Gelabert, E.; Jover, M.; Guillamat, R.; Mayoral, F.; Gornemann, I.; Canellas, F.; et al. Coping Strategies and Postpartum Depressive Symptoms: a Structural Equation Modelling Approach. Eur. Psychiatry 2015, 30, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warfa, N.; Harper, M.; Nicolais, G.; Bhui, K. Adult attachment style as a risk factor for maternal postnatal depression: a systematic review. BMC Psychol. 2014, 2, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianciardi, E.; Vito, C.; Betrò, S.; De Stefano, A.; Siracusano, A.; Niolu, C. The anxious aspects of insecure attachment styles are associated with depression either in pregnancy or in the postpartum period. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2020, 19, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, R. , Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. Springer. New York, 1984.

- Da Costa, D.; Larouche, J.; Dritsa, M.; Brender, W. Psychosocial correlates of prepartum and postpartum depressed mood. J. Affect. Disord. 2000, 59, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Tychey, C.; Spitz, E.; Briançon, S.; Lighezzolo, J.; Girvan, F.; Rosati, A.; Thockler, A.; Vincent, S. Pre- and postnatal depression and coping: a comparative approach. J. Affect. Disord. 2005, 85, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honey, K. Predicting postnatal depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2003, 76, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faisal-Cury, A.; Tedesco, J.J.A.; Kahhale, S.; Menezes, P.R.; Zugaib, M. Postpartum depression: in relation to life events and patterns of coping. Arch. Women’s Ment. Heal. 2004, 7, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Zotes, A.; Labad, J.; Martín-Santos, R.; García-Esteve, L.; Gelabert, E.; Jover, M.; Guillamat, R.; Mayoral, F.; Gornemann, I.; Canellas, F.; et al. Coping strategies for postpartum depression: a multi-centric study of 1626 women. Arch. Women’s Ment. Heal. 2015, 19, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardino, C.M.; Schetter, C.D. Coping during pregnancy: a systematic review and recommendations. Heal. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 8, 70–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Jiang, X.; Yao, J.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Pang, M.; Chiang, C.L.V. Depression, Social Support, and Coping Styles among Pregnant Women after the Lushan Earthquake in Ya’an, China. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0135809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pakenham, K.I.; Smith, A.; Rattan, S.L. Application of a stress and coping model to antenatal depressive symptomatology. Psychol. Heal. Med. 2007, 12, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Guo, X. The mediating role of coping styles in the relationship between perceived social support and antenatal depression among pregnant women: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besser, A.; Priel, B. Trait vulnerability and coping strategies in the transition to motherhood. Curr. Psychol. 2003, 22, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robakis, T.K.; Zhang, S.; Rasgon, N.L.; Li, T.; Wang, T.; Roth, M.C.; Humphreys, K.L.; Gotlib, I.H.; Ho, M.; Khechaduri, A.; et al. Epigenetic signatures of attachment insecurity and childhood adversity provide evidence for role transition in the pathogenesis of perinatal depression. Transl. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment (2nd.ed.). Basic Books. New York, NY: (1969/1982).

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 2. Separation. Basic Books. New York, NY: (1973).

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 3. Loss. Basic Books. New York, NY: (1980).

- Sherman, L.J.; Rice, K.; Cassidy, J. Infant capacities related to building internal working models of attachment figures: A theoretical and empirical review. Dev. Rev. 2015, 37, 109–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretherton, I. New perspectives on attachment relations: Security, communication, and internal working models. In J. Osofsky (Ed.), Handbook of infant development. New York: Wiley. 1987 (pp. 1061-1100).

- Brennan K., A. , Clark C.L., Shaver P. R. Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships. Guilford Press. New York, NY. 1998 (pp. 46-76).

- Jinyao, Y.; Xiongzhao, Z.; Auerbach, R.P.; Gardiner, C.K.; Lin, C.; Yuping, W.; Shuqiao, Y. INSECURE ATTACHMENT AS A PREDICTOR OF DEPRESSIVE AND ANXIOUS SYMPTOMOLOGY. Depression Anxiety 2012, 29, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagan, O.; Facompré, C.R.; Bernard, K. Adult attachment representations and depressive symptoms: A meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 236, 274–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bifulco, A.; Moran, P.M.; Ball, C.; Bernazzani, O. Adult attachment style. I: Its relationship to clinical depression. Chest 2002, 37, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, M.; Hayashi, M.; Kamibeppu, K. The relationship between attachment style and postpartum depression. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2014, 16, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, F.G.; Mauricio, A.M.; Gormley, B.; Simko, T.; Berger, E. Adult Attachment Orientations and College Student Distress: The Mediating Role of Problem Coping Styles. J. Couns. Dev. 2001, 79, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, F.G.; Mitchell, P.; Gormley, B. Adult attachment orientations and college student distress: Test of a mediational model. J. Couns. Psychol. 2002, 49, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Heppner, P.P.; Mallinckrodt, B. Perceived coping as a mediator between attachment and psychological distress: A structural equation modeling approach. J. Couns. Psychol. 2003, 50, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, M.S.; Medway, F.J. Adolescents’ attachment and coping with stress. Psychol. Sch. 2004, 41, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birnbaum, G.E.; Orr, I.; Mikulincer, M.; Florian, V. When Marriage Breaks Up-Does Attachment Style Contribute to Coping and Mental Health? J. Soc. Pers. Relationships 1997, 14, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M.; Florian, V.; Weller, A. Attachment styles, coping strategies, and posttraumatic psychological distress: The impact of the Gulf War in Israel. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 64, 817–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buelow, S.A.; Lyddon, W.J.; Johnson, J.T. Client attachment and coping resources. Couns. Psychol. Q. 2002, 15, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M. , Florian V. The relationship between adult attachment styles and emotional and cognitive reactions to stressful events. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships. The Guilford Press. 1998 (pp. 143–165).

- Schmidt, S.; Nachtigall, C.; Wuethrich-Martone, O.; Strauss, B. Attachment and coping with chronic disease. J. Psychosom. Res. 2002, 53, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F.; Weintraub, J.K. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 56, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Connor-Smith, J. Personality and Coping. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2010, 61, 679–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moos, R.H. Schaefer J.A. Coping Resources and Processes: Current Concepts and Measures. In: Goldberger, L. and Breznitz, S., Eds., Handbook of Stress: Theoretical and Clinical Aspects, 2nd Edition, The Free Press, New York, 1993 (pp 234-257).

- Roth, S.; Cohen, L.J. Approach, avoidance, and coping with stress. Am. Psychol. 1986, 41, 813–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, E.A.; Edge, K.; Altman, J.; Sherwood, H. Searching for the structure of coping: A review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 216–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carver, C.S. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the Brief COPE. Int. J. Behav. Med. 1997, 4, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F.; Rockwood, N.J. Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: Observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behav. Res. Ther. 2017, 98, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, E.; Mzembe, G.; Mwambinga, M.; Truwah, Z.; Harding, R.; Ataide, R.; Larson, L.M.; Fisher, J.; Braat, S.; Pasricha, S.; et al. Prevalence of early postpartum depression and associated risk factors among selected women in southern Malawi: a nested observational study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCauley, M.; White, S.; Bar-Zeev, S.; Godia, P.; Mittal, P.; Zafar, S.; Broek, N.v.D. Physical morbidity and psychological and social comorbidities at five stages during pregnancy and after childbirth: a multicountry cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e050287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellomo, A.; Severo, M.; Petito, A.; Nappi, L.; Iuso, S.; Altamura, M.; Marconcini, A.; Giannaccari, E.; Maruotti, G.; Palma, G.L.; et al. Perinatal depression screening and prevention: Descriptive findings from a multicentric program in the South of Italy. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 962948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliszewska, K.; Bidzan, M.; Świątkowska-Freund, M.; Preis, K. Personality type, social support and other correlates of risk for affective disorders in early puerperium. Ginekol. Polska 2016, 87, 814–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, C.E.; Janssen, P.A.; Singer, J. Identifying women at-risk for postpartum depression in the immediate postpartum period. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2004, 110, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenuti, P.; Ferrara, M.; Niccolai, C.; Valoriani, V.; Cox, J.L. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale: validation for an Italian sample. J. Affect. Disord. 1999, 53, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergink, V.; Kooistra, L.; Lambregtse-van den Berg, M.P.; Wijnen, H.; Bunevicius, R.; van Baar, A.; Pop, V. Validation of the Edinburgh Depression Scale during pregnancy. J. Psychosom. Res. 2011, 70, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, L.; Carothers, A.D. The Validation of the Edinburgh Post-natal Depression Scale on a Community Sample. Br. J. Psychiatry 1990, 157, 288–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, R.C. , Le H.N., Somberg R. Review of screening instruments for postpartum depression. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2005; 8:141-53. [CrossRef]

- Cena, L.; Mirabella, F.; Palumbo, G.; Gigantesco, A.; Trainini, A.; Stefana, A. Prevalence of maternal antenatal and postnatal depression and their association with sociodemographic and socioeconomic factors: A multicentre study in Italy. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 279, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, K.-P.; Chiu, T.-H.; Huang, C.-L.; Ho, M.; Lee, C.-C.; Wu, P.-L.; Lin, C.-Y.; Liau, C.-H.; Liao, C.-C.; Chiu, W.-C.; et al. Different cutoff points for different trimesters? The use of Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale and Beck Depression Inventory to screen for depression in pregnant Taiwanese women. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2007, 29, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozinszky, Z.; Dudas, R.B. Validation studies of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale for the antenatal period. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 176, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.L.; Holden, J.M.; Sagovsky, R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry 1987, 150, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.K.; Kim, J.J.; Park, Y.G.; Ko, H.S.; Park, I.Y.; Shin, J.C. The Simplified Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) for Antenatal Depression: Is It a Valid Measure for Pre-Screening? Int. J. Med Sci. 2012, 9, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, C.-L. Can we identify mothers at risk for postpartum depression in the immediate postpartum period using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale? J. Affect. Disord. 2004, 78, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanuma-Takahashi, A.; Tanemoto, T.; Nagata, C.; Yokomizo, R.; Konishi, A.; Takehara, K.; Ishikawa, T.; Yanaihara, N.; Samura, O.; Okamoto, A. Antenatal screening timeline and cutoff scores of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale for predicting postpartum depressive symptoms in healthy women: a prospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, K.A. , Clark C.L., Shaver P.R. Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In J. A. Simpson &W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships New York: Guilford. 1998 (pp. 46–76).

- Iles, J.; Slade, P.; Spiby, H. Posttraumatic stress symptoms and postpartum depression in couples after childbirth: The role of partner support and attachment. J. Anxiety Disord. 2011, 25, 520–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, R.; Monteiro, F.; Canavarro, M.C.; Fonseca, A. The role of emotion regulation difficulties in the relationship between attachment representations and depressive and anxiety symptoms in the postpartum period. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 238, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picardi, A. , Vermigli P., Toni A., D’Amico R., Bitetti D., Pasquini P. Il questionario “experiences in close relationships” (ECR) per la valutazione dell’attaccamento negli adulti: Ampliamento delle evidenze di validità per la versione italiana. Ital J Psychopathol. 2002; 8:282–94.

- Dias, C.; Cruz, J.F.; Fonseca, A.M. The relationship between multidimensional competitive anxiety, cognitive threat appraisal, and coping strategies: A multi-sport study. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2012, 10, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulus, D.; Coulter, T.J.; Trotter, M.G.; Polman, R. Stress and Coping in Esports and the Influence of Mental Toughness. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, L. Repertorio delle scale di valutazione in psichiatria. Firenze: SEE Firenze. (2000).

- Tabachnick, B.G. , Fidell L.S. Using multivariate statistics (7th ed.). Pearson. (2018).

- Schreiber, J.B.; Nora, A.; Stage, F.K.; Barlow, E.A.; King, J. Reporting Structural Equation Modeling and Confirmatory Factor Analysis Results: A Review. J. Educ. Res. 2006, 99, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, S.L. Structural equation modelling made easy: for business and social science research using SPSS and AMOS. Washington: independently published. (2018).

- Hair, J.F. , Black W.C., Babin B.J., Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis (7th edition). New Jersey: Prentice Hall. (2010).

- Bartlett, M.S. THE EFFECT OF STANDARDIZATION ON A χ2 APPROXIMATION IN FACTOR ANALYSIS. Biometrika 1951, 38, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norusis, M. SPSS 16.0 Advanced Statistical Procedures Companion; Prentice Hall Press: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B. M. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. New York: Routledge. (2010).

- Schumacker, R.E. , Lomax R.G. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling (4th Ed.). New York: Routledge. (2016).

- Azale, T.; Fekadu, A.; Medhin, G.; Hanlon, C. Coping strategies of women with postpartum depression symptoms in rural Ethiopia: a cross-sectional community study. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monk, C.; Leight, K.L.; Fang, Y. The relationship between women’s attachment style and perinatal mood disturbance: implications for screening and treatment. Arch. Women’s Ment. Heal. 2008, 11, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, T.; Galves, A.; Dickinson, L.M.; Perez, M.d.J.D. Stress, Coping, and Health: A Comparison of Mexican Immigrants, Mexican-Americans, and Non-Hispanic Whites. J. Immigr. Minor. Heal. 2005, 7, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M.; Florian, V. Appraisal of and Coping with a Real-Life Stressful Situation: The Contribution of Attachment Styles. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 21, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, D.L.; Wei, M. Adult Attachment and Help-Seeking Intent: The Mediating Roles of Psychological Distress and Perceived Social Support. J. Couns. Psychol. 2005, 52, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, K.; Horowitz, L.M. Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 61, 226–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guttmann-Steinmetz, S.; Crowell, J.A. Attachment and Externalizing Disorders: A Developmental Psychopathology Perspective. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2006, 45, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazan, C.; Shaver, P. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 52, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrine, R.M. Stress and college persistence as a function of attachment style Journal of the First Year Experience and Students in Transition. 1: 11, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Elwood, L.S.; Williams, N.L. PTSD–Related Cognitions and Romantic Attachment Style as Moderators of Psychological Symptoms in Victims of Interpersonal Trauma. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 26, 1189–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortuna, K.; Roisman, G.I. Insecurity, stress, and symptoms of psychopathology: contrasting results from self-reports versus interviews of adult attachment. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2008, 10, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hankin, B.L.; Kassel, J.D.; Abela, J.R.Z. Adult Attachment Dimensions and Specificity of Emotional Distress Symptoms: Prospective Investigations of Cognitive Risk and Interpersonal Stress Generation as Mediating Mechanisms. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2005, 31, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maunder, R.G.; Lancee, W.J.; Nolan, R.P.; Hunter, J.J.; Tannenbaum, D.W. The relationship of attachment insecurity to subjective stress and autonomic function during standardized acute stress in healthy adults. J. Psychosom. Res. 2006, 60, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, N.L. Working models of attachment: Implications for explanation, emotion, and behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 71, 810–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Antepartum depression | Postpartum depression | |

| Age (mean, SD) | 32.2 (5.9) | 32.9 (5.2) |

| Educational Level (%) | ||

| Primary school | 1 (0.42) | 1 (0.34) |

| Secondary school | 37 (15.8) | 34 (11.8) |

| Post-Secondary school | 116 (49.5) | 155 (54.0) |

| Higher education | 79 (33.7) | 96 (33.4) |

| Parity (primiparous) (%) | 111 (47.4) | 151 (52.6) |

| Marital status (%) | ||

| Married or paired | 230 (98.2) | 286 (99.6) |

| Some medical condition | ||

| during pregnancy (%) | 64 (27.3) | 85 (29.6) |

| Complication during pregnancy (%) | 154 (65.8) | 278 (96.8) |

| Family history of psychiatric | ||

| problems (%) | 147 (62.8) | 141 (49.1) |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).