1. Introduction

In a clinical context, the repair of critical bone defects is an important topic; consequently, it is necessary to develop scaffold materials conducive to bone tissue regeneration [

1]. For patient-individual, the 3D-printing materials used for bone defect repair should not only meet the strength and degradation-rate requirements, but also have biological activity, in order to promote the proliferation and differentiation of bone tissue stem cells [

2,

3]. In addition, scaffolds are also required to be able to promote vascular regeneration and prevent excessive inflammatory reactions. Therefore, we believe that introducing functional magnesium ions into 3D-printed scaffolds is a strategy worth exploring to improve the biological activity of scaffolds.

Magnesium is an important and essential element for the human metabolism, and it plays an important role in promoting new bone formation [

4,

5]. Furthermore, it plays an important role in angiogenesis in the early stages of bone-defect repair [

6]. Research has shown that magnesium ions can also play an important role in immune regulation during bone repair[

7]. In the early inflammatory stage of bone repair, monocytes can be induced into macrophages, which is beneficial for clearing excess and ineffective bone tissue. Mg

2+ can also induce macrophages to secrete anti-inflammatory and osteogenic factors, thereby promoting bone tissue regeneration. It has been reported that adding magnesium to titanium alloy, tricalcium phosphate [

8,

9], and other bone repair materials can improve their osteogenic properties [

10]. Mg

2+ is believed to activate the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, consequently promoting the proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of bone mesenchymal stem cells[

11,

12].

Micro-nano bioactive glass (MNBG) prepared using the sol–gel method has excellent biological activity, uniform size distribution, and is of a regular shape [

13,

14]. It has great potential to be applied as bone repair material[

15]. When magnesium is added to MNBG, magnesium ions can be released simultaneously with silicon and calcium ions [

16,

17]. This is an effective means to exert the biological activity of magnesium ions in the scaffold.

For the bridging of critical-size bone defects scaffolds that can gradually be replaced by newly formed bone are preferred. An effective strategy to tailor the scaffold’s degradation rate to the rate of normal bone growth is combining degradable polymers that are suitable for 3D printing, with micro-nano bioactive glass with appropriate degradation rate[

18,

19]. The selection of degradable polymers for 3D printing has lon

g been an important research topic, and there have been related reports in previous studies [

20,

21,

22]. The physical and chemical properties of composite scaffolds need to match the properties of the bone tissue [

23], and the degradability of polymers can be tailored to adjust the overall degradation rate of the scaffold [

24,

25].

Soluble polymer materials such as poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) and polycaprolactone (PCL) are biocompatible and degradable [

26,

27]. According to research reports, scaffolds prepared from PLGA have a mechanical strength matching that of cancellous bone, and their degradation rate can meet the needs of bone-defect repair. PLGA can be melted for printing [

28,

29], or it can be printed dissolved in dioxane at a low temperature of -20 ℃ [

30,

31]. The above methods have high requirements in terms of temperature conditions, and 3D-printing PLGA at room temperature instead is a desirable method. PCL also has osteogenic properties when combined with bioactive glass [

32,

33]. However, PCL with high molecular weight often has a slower degradation rate than PLGA; thus, when chosen as scaffold material, it is advisable to choose PCL with a slightly lower molecular weight. In addition, when PCL and PLGA are miscible, PCL can reduce the viscosity of the PLGA solution and the fluid formed by adding bioglass is more suitable for extrusion printing. Moreover, bioglass can adjust the pH of the surrounding environment to minimize the negative impact of lactic acid produced during PLGA degradation.

Previous studies have shown that micro-nano bioactive glass (MNBG) can promote new bone formation by releasing ions and inducing mineralization. The released Si and Ca ions in body fluids can promote the proliferation and differentiation of osteoblasts [

34,

35,

36,

37]. The MgMNBG prepared in this study can simultaneously release magnesium, silicon, calcium related ions, and the impact of ions on osteogenic related cells is worth exploring.

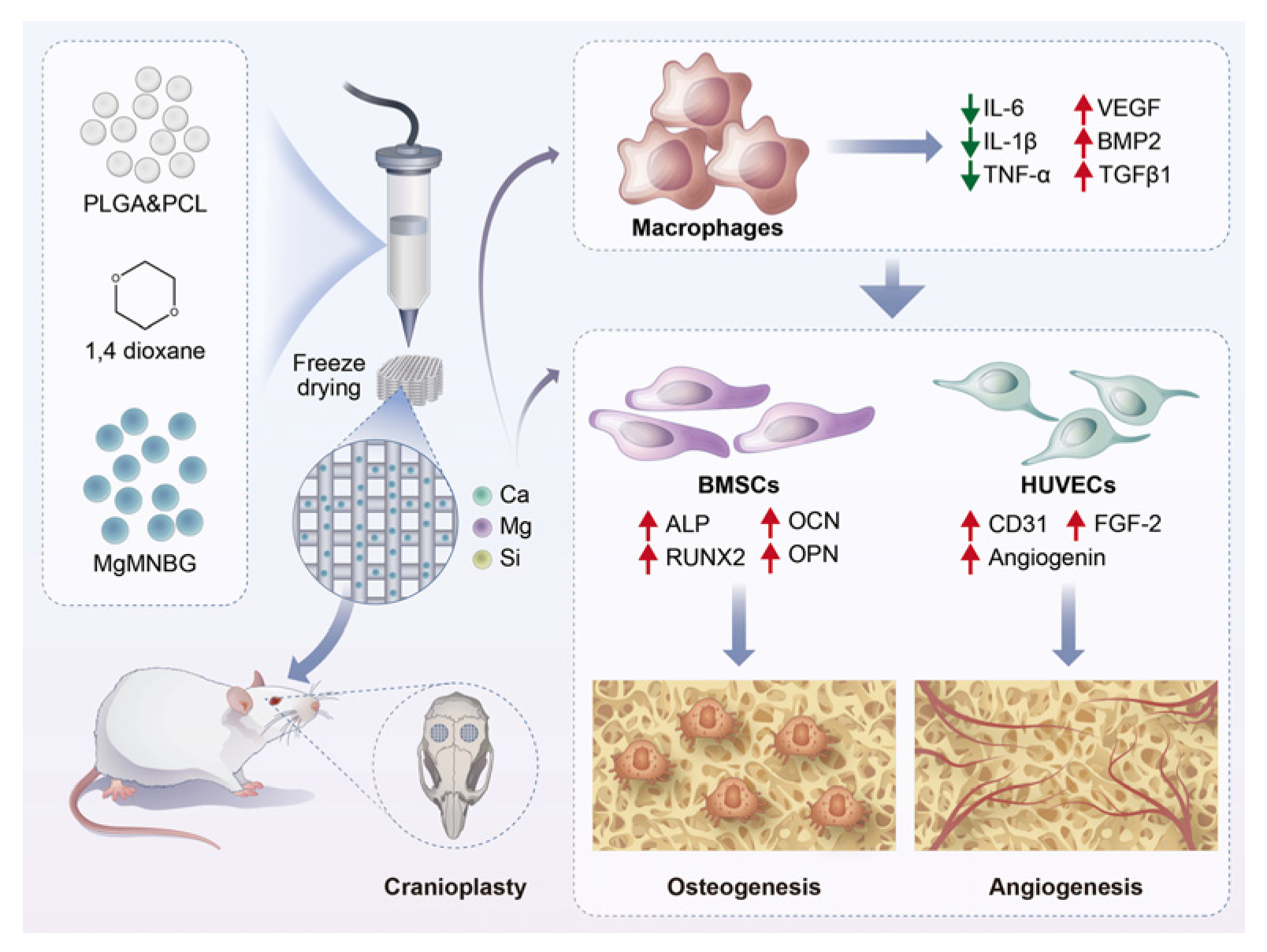

In this study, we investigated the effect of MgMNBG on osteogenic performance and its impact on angiogenesis. We hope to explore some mechanisms by which MgMNBG affects osteoblast differentiation and vascular regeneration. To examine the effect of MgMNBG on immune regulation through in vitro experiments, the effect of MgMNBG on macrophage phenotype and cytokine secretion was studied.

We used 3D printing to prepare each group of composite scaffolds, and evaluated their physical and chemical properties and biocompatibility, as well as their capacity for bone-defect repair through in vivo experiments. The results were consistent with the in vitro experiments. Based on these results, it can be expected that composite scaffolds with potential for practical application can be developed.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Preparation of MNBG and MgMNBG

The MgMNBG was prepared as follows: Briefly, 8 g of dodecylamine (Aladdin reagent) was added to a mixture of 50 mL deionized water and 200 mL anhydrous ethanol (Guangzhou Chemical Reagent Factory) and stirred at 37 °C until it dissolved. Then, 32 mL tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) (Guangzhou Chemical Reagent Factory) was added at a rate of 1 mL/min, while continuing to stir at 37 °C. After 1 hour of hydrolysis, 21 mL triethyl phosphate (Guangzhou Chemical Reagent Factory) was added at 1 mL/min, and the mixture continued to react for 1 h. Finally, 27.5 g calcium nitrate tetrahydrate and 7.5 g magnesium nitrate hexahydrate were dissolved in 50 mL deionized water; the solution was slowly added to the above mixed suspension, and the stirring was continued until the hydrolysis of each component was complete, to obtain a uniformly mixed suspension. After aging for 1 day, the suspension was centrifuged to obtain a white gel. This gel was washed with deionized water and ethanol 3 times, dried, and then treated in a muffle furnace at 650 ℃ for 3 h with heating and cooling rates of 2 ℃/min, to finally obtain MgMNBG powder. The obtained powder is ground and sieved (38 μm).The preparation process of MNBG did not contain magnesium nitrate hexahydrate; instead 33 g calcium nitrate tetrahydrate was used to participate in the reaction and the rest of the steps were the same.

2.2. Preparation of PLGA/PCL, PLGA/PCL/MNBG, and PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG scaffolds

The model of the 3D printer used was 3D Bio-Architect® TB MINI (Genofei Biotechnology Co, Ltd). Composite scaffolds with different mass ratios of MgMNBG and polymer (PLGA/PCL) were prepared via 3D printing at room temperature. The weight ratio of PLGA, PCL, and MgMNBG was 7:3:4. The preparation method was as follows: 1.5 g PCL (Mw=4×103) and 3.5 g PLGA (Mw=8×104, 75/25) were dissolved in 2.5 mL 1,4-dioxane and 2 g MgMNBG was added under continuous stirring. The solution was then transferred to the cartridge; and extruded at room temperature at 2.4–3.2 MPa, printing speed is 6-13mm/s. The distance between strands was set to 300 μm and scaffolds of different shapes and sizes were printed. After printing, the scaffolds were frozen at -20 ℃, stored for 24 h, and finally freeze-dried for 48 h. The preparation method of PLGA/PCL/MNBG scaffolds was consistent with the above method. PLGA/PCL scaffolds were printed with a weight ratio of PLGA:PCL=7:3. Other methods were consistent with the preparation methods of PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG.

The PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG scaffold was scanned using Micro-CT (Nikon 160H, Japan), the tube voltage was 75 kV, the tube current was 104 μA, the exposure time was 250 ms, and the number of projections was 1000 frames.

2.3. Testing and characterization of the bioglass and the composite scaffolds

2.3.1. Microscopic topography analysis and energy spectrum analysis

High-resolution field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, Merlin Carl Zeiss Jena, Germany) was used to analyze the microscopic topography of each group of 3D-printed scaffolds. In order to improve the conductivity of the samples, the porous scaffolds were sprayed with Pt. To investigate the elemental composition of the scaffolds, surface energy spectroscopy (EDS) analysis was performed on the scaffold surfaces (FE-SEM, Merlin Carl Zeiss Jena, Germany) .

2.3.2. Analysis of particle size distribution and surface pore structure of MNBG and MgMNBG

After MgMNBG or MNBG were dispersed in a certain amount of solvent, the particle size distribution was measured using Zetasizer Nano (Zetasizer Nano ZS, Malvern Instruments, UK). The specific surface area of the MgMNBG microspheres was measured using a specific surface area and porosimeter (BET, NOVA4200e, Quantachrome, USA). First, the powder was degassed at 250 °C for 4 h under vacuum conditions, and then the nitrogen adsorption and desorption points were measured under different relative pressures in a nitrogen atmosphere. The Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method was used to analyze the specific surface area of the microspheres. According to the final results of nitrogen adsorption and desorption isotherms, the Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) method was used to calculate the pore volume and pore size distribution on the surface of the microspheres.

2.3.3. Crystal characterization

Crystal images of MNBG, MgMNBG, and each group of scaffolds before and after mineralization were determined using an X-ray diffraction analyzer (XRD, Pert3Power, PANalytical, NLD). The experimental conditions used were Cu target Kα rays, the voltage was 40KV, the current was 100 mA, and the scanning range 2θ was 10°–90°.

2.3.4. Chemical structure analysis of bioglass

MNBG and MgMNBG were qualitatively examined using a Fourier-transform infrared spectrometer (FTIR, Vector33, Bruker, Germany). The test method was as follows: the KBr powder tableting method was adopted; the samples to be tested and the KBr powder were mixed and pressed into tablets according to a mass ratio of 1:100, and the functional groups of the sample are determined via the absorption spectrum of the sample at different wavelengths. The selected wavelength range was 400~2000 cm-1.

2.3.5. Porosity test of scaffolds

For the porosity test Archimedes’ principle was adopted. First, the dry weight of the scaffolds (5 parallel samples) M0 was measured, then the scaffolds were immersed in well plates with absolute ethanol. The orifice plate was put under vacuum so that the ethanol entered the pores, then the wet weight M2 and floating weight M1 were determined after turning off the vacuum pump (porosity=(M2-M0)/(M2-M1)×100%). The measurement was performed for 5 samples per group.

2.3.6. Mechanical properties

In order to study the mechanical properties of the scaffolds, a universal testing system (Instron5967, INSTRON, USA) was used. The scaffolds were printed as cuboids, with bottom dimensions of 0.8 cm×0.8 cm and a height of 2 cm. The dimensions of each scaffold were measured individually, and the compression experiment was carried out at a speed of 0.5 mm/min. When the deformation of the stress–strain curve was 10%, the slope represented the compressive modulus, and the measurement was repeated for 5 samples.

2.3.7. pH of scaffolds in simulated body fluid (SBF)

The 3D-printed composite scaffolds were soaked in SBF at a solid-liquid ratio of 1 mg/mL for different times, and pH was measured with a pH meter (Shanghai Yidian Scientific Instrument Co, Ltd). The scaffolds were placed in 100 mL polyethylene bottles separately, and corresponding SBF was added. Then, they were placed on a shaker at 100 rpm and shaken at 37 °C. The pH of the SBF was measured after 1, 3, 7, 14, 21, and 28 days, and the measurement was repeated for 5 samples.

2.3.8. In vitro degradation performance

The degradation properties of 3D-printed scaffolds were measured using SBF. First, the mass of the scaffolds in the dry state was determined, denoted as W

0, then the scaffolds were immersed in SBF at a solid-liquid ratio of 1 mg/mL, and placed on a shaker with a rotation speed of 100 rpm at a temperature of 37 °C. After 1, 3, 7, 14, 21, and 28 days, the scaffolds were taken out, rinsed with deionized water, dried in an oven, and then weighed to record the mass as W

t, with 5 parallel samples in each group. The scaffold degradation mass loss (weight loss) was calculated using the following formula:

W0 is the original weight of the scaffold, and Wt is the mass of the scaffold after degradation at different times.

2.3.9. Ion release from each group of scaffolds in SBF solution

Each group of scaffolds was immersed in SBF at a solid-liquid ratio of 10 mg/L in bottles separately, and then placed on a constant temperature shaker at 37 ° C and 100 rpm for 1, 4, 7, and 14 days before being sampled separately. An inductively coupled plasma emission spectrometer (ICP, PS1000-AT, Leeman, USA) was used to measure the ion release from the scaffolds at different time points in SBF. The measurement was repeated for 5 samples.

2.4. Evaluation of osteogenesis in vitro

2.4.1. Preparation of extracts and determination of ion concentration

MgMNBG and MNBG powders were sterilized at high temperatures in an autoclave and dispersed in DMEM (high glucose) at a concentration of 20 mg/mL. They were placed on a shaker at a temperature of 37 °C and a rotating speed of 100 rpm for 24 h. After centrifugation at 8000 rpm for 5 min, the extracts were filtered through a microporous membrane (0.22 μm). Finally, the medium was diluted 20 times with high-glucose medium, and 10% FBS and 1% P/S (penicillin/streptomycin) were added to obtain the extract medium. The concentration of each ion in the extract was determined using an inductively coupled plasma emission spectrometer (ICP, PS1000-AT, Leeman, USA).

2.4.2. The effect of bioglass extracts on the viability and proliferation of mBMSCs

To culture mouse bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (mBMSCs) for live–dead staining, 1.5×104 cells per well were plated in 48-well plates. After adhesion, the culture medium was replaced with the extraction medium of MgMNBG and MNBG. Medium without the extract was used as the blank control. The medium was changed every 2–3 days. After 1, 4, and 7 days, a live–dead staining kit (Beyotime) was used to carry out the live–dead staining of the cells in the plates.

To measure cell proliferation mBMSCs were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 5×103/well. After the cells adhered, the medium was replaced with the above-mentioned extracts. The medium was changed every 2–3 days. When each group was cultured with mBMSCs for 1, 4, and 7 days cell proliferation was detected using the CCK-8 kit (Cell Counting Kit-8) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (DOJINDO, Japan).

2.4.3. Cell proliferation on scaffolds

Each composite material was used to print circular scaffolds with a diameter of 9 mm and 4 layers. The scaffolds were placed in 48-well plates, sterilized with 75% alcohol and UV light for 24h, and then washed three times with PBS. The irradiated scaffolds were transferred to the new 48-well plate, and 5×104 cells were seeded on each scaffold. After adhesion, the complete culture medium was changed the next day. One or four days later, the live–dead staining kit (Beyotime) was used to dye the cells on the scaffolds’ surface. Photos were taken under an inverted fluorescence microscope (ZEISS, Germany).

The sterilized scaffolds were placed in 48-well plates, then mBMSCs were seeded at a density of 2×104/well, and the complete medium was changed every 2 days. The medium was removed after cultivation for 1, 4, and 7 days, and the scaffolds were transferred to a new 48-well plate. A volume of 250 μL complete medium (containing 10% CCK-8) was added to each well and incubated in an incubator at 37 °C for 60 min. After that, 100 μL of the CCK-8 medium from each well was slowly and carefully transferred to a 96-well plate.

Then, the plate was placed into a microplate reader and a wavelength of 450 nm was used to measure the light absorption. The experiment was performed three times.

2.4.4. Alizarin red staining

The mBMSCs were seeded into a 48-well plate at a density of 1.5×104/well. After adhering, the culture medium was replaced with osteo-induction extraction medium of MgMNBG and MNBG (osteogenic induction supplements were 50 ng/mL ascorbic acid, 10 mM sodium β-glycerophosphate, and 10 nM dexamethasone). The osteoinduction medium without the extract was set as the blank control. Alizarin red staining solution (Beyotime) was used for staining after eight days of cultivation, and the steps were as follows: each well was washed three times with PBS; then, 4% paraformaldehyde was added to each well for 20 min at room temperature; after that, ultrapure water was used to wash each well three times; 200 μL of alizarin red staining working solution was added to each well; and the samples were placed on a shaker at room temperature for 5 min. After that, the staining solution was aspirated, samples were washed with ultrapure water twice, photographed with a camera, and finally observed and photographed under an inverted fluorescence microscope (ZEISS, Germany).

2.4.5. Alkaline phosphatase staining and quantitative analysis of ALP

The mBMSCs were cultured and seeded into 48-well plates at a cell concentration of 1.5×104/well. After the cells adhered, the culture medium was replaced with the above 3 kinds of osteogenic induction media based on control medium or the bioglass extracts. The medium was changed every 2–3 days. After culturing for 7 days, the medium was removed and the samples were washed three times with PBS. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min and washed three times with PBS again. Then, 200 μL of prepared BCIP/NBT staining working solution (Beyotime, China) was added to each well and the samples were incubated at room temperature for 30 min in the dark. After that, the staining solution was removed and the samples were washed three times with PBS. The images of ALP staining were taken using an inverted microscope.

Quantitative ALP detection: The mBMSCs were cultured and seeded into 24-well plates at a cell concentration of 3.5×104/well. After culturing for 24 h, the cell culture medium was replaced with the above 3 kinds of media containing osteogenic induction supplements. The medium was changed every 2–3 days. After 7 or 14 days, the culture plate was placed on ice and the samples were washed with PBS. A total of 100 μL of lysis solution (10 mL RIPA+100 μL PMSF, ratio 100:1) was added to each well, the samples were lysed for 30 minutes, pipetted into eppendorf tubes and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 15 minutes. Total protein was detected using a BCA kit (Thermo Fisher), then detected using a quantitative ALP detection kit (Beyotime). The detection was carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The experiment was performed three times.

2.4.6. Expression of osteogenesis-related genes

The mBMSCs were seeded into 24-well plates at 3.5×104 cells/well. After 24 h, the culture medium was replaced with the above 3 kinds of medium containing osteogenic induction, and the medium was changed every 2 days. After 7 and 14 days of culture, total RNA was extracted from each group and then reverse transcribed into cDNA. Then, real-time quantitative PCR was used to detect related genes (Life Technologies, US). The detected genes were ALP, OPN, OCN, COL1, RUNX2 and GAPDH, which was the housekeeping gene (Thermo, US). The experiment was repeated 3 times. Using the blank group as the control group, calculate the relative expression levels of each gene using 2-ΔΔCT.

2.5. Phenotypic regulation of macrophages by MgMNBG and MNBG extracts

2.5.1. Phenotypic detection of macrophages

CD11c and CD206 were selected as specific marker molecules on the surface of macrophages, and flow cytometry (FACSCALIBUR, BD, US) was used to detect the overall polarization state of macrophages cultured in MgMNBG and MNBG extracts. The effect of the extracts on the polarization phenotype of RAW 264.7 macrophages was investigated after cultured for 4 days.

Raw 264.7 macrophages were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 1.5×105 cells/well, and the solution was changed once a day. When the density reached 80%, the culture medium was replaced with the extract medium prepared above. After 4 days of cultivation, the cultured cells were removed and tested using flow cytometry. FITC anti-mouse CD11c and PE anti-mouse CD206 (Ebiscience, US) are used for labeling macrophages.

2.5.2. Gene expression related to macrophage inflammation and pro-osteogenic factors

Raw 264.7 macrophages were seeded into 24-well plates at a density of 3×104 cells/well, and the solution was changed once a day. After four days of cultivation, the well plates were removed and RNA was extracted from each well and reverse-transcribed into cDNA. Then, RT-PCR was used to detect the mRNA expression of inflammation-related genes IL-1β,TNF-α,IL-6,IL-10,IL-1ra and Arginase. Expression of pro-osteogenic factors related genes VEGF,TGFβ1,TGFβ3 and BMP-2 .The experiment was repeated 3 times.

2.6. Investigation of MgMNBG and MNBG extracts promoting angiogenesis in vitro

2.6.1. Preparation of endothelial medium extract of MNBG and MgMNBG

For the preparation of MgMNBG/ECM and MNBG/ECM extracts 1 g MNBG or MgMNBG was sterilized, dispersed in 50 mL basal endothelial cell culture medium (ECM, ZhongQiaoxinzhou, Shanghai), placed on a 37 ℃ shaker, and shaken at 100 rpm for 24 h. After the extraction was completed, the culture medium was centrifuged at 5000 rpm. The supernatant was filtered and sterilized with a 0.22 μm filter, the extract was diluted 20 times, and then 5 % FBS and endothelial medium supplements were added to obtain the extraction media, which were labeled as MgMNBG/ECM or MNBG/ECM. ECM complete culture medium was set as the control.

2.6.2. CD31 immunofluorescence staining and quantitative fluorescence analysis

HUVECs were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 4×103 cells/well. After the cells adhered, the medium was replaced with MgMNBG/ECM or MNBG/ECM. The complete culture medium was set as the control, and the medium was changed every day. After 3 days, the medium was aspirated and cells were fixed via washing with PBS, addition of 200 μL 4% paraformaldehyde per well, and incubation for 30 minutes. After that, samples were washed 3 times with PBS, treated with 0.5% TritonX-100 for 10 min, blocked with BSA/PBS solution (3%) for 1 h, the CD31 antibody was diluted with 1% BSA/PBS solution at 1:80,samples incubated in 100 μL of CD31 antibody (Abcam,US) overnight in a refrigerator at 4 ℃. On the second day, samples were washed three times with PBS, then incubated with a secondary antibody, namely goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Alexa 488,Abcam,US), the secondary antibody was diluted with 1% BSA/PBS solution at 1:200. Then, the nuclei were dyed with DAPI (dilute with PBS at 1000 times) for 5 minutes. Observation and photography were carried out using an inverted fluorescence microscope. Furthermore, fluorescence intensity was quantified and analyzed using ImageJ software.

2.6.3. Quantitative analysis of angiogenesis-related gene expression

HUVECs were seeded into 24-well plates at a density of 8×104 cells/well. After 24 h, when the cells adhered, the medium was replaced with the above 3 kinds of ECM culture media, and the medium was changed every day. After 3 days of culture, total RNA was extracted from each group and then reverse-transcribed into cDNA. Then, real-time quantitative PCR was used to detect related genes. The detected genes were angiogenin, fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2), and Stromal cell derived growth factor (SDF), and GAPDH was used as housekeeping gene. The experiment was repeated 3 times.

2.7. In vivo experimental evaluation

The rat skull defect model was used to evaluate the repair of the bone defect. The scaffolds were divided into 4 groups, the blank group,the PLGA/PCL/MNBG group,the PLGA/PCL group,and the PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG group. The size of the scaffolds was 4.6 ± 0.2 mm in diameter and 3 layers were printed.

The specific method is as follows. A total of 20 adult male rats (250–300 g, SD, purchased from Guangzhou Pharmaceutical University, Ethics Certification Committee No. Gdpulacspf 2017517) were anesthetized with chloral hydrate (10%, prepared with normal saline) after general anesthesia (6–10 mL per rat according to the weight of the rats). After sterilizing the head area to be operated on with iodophor, a 1.4–1.6 cm incision was made along the centerline of the skull, and the skin tissue on the skull was separated to both sides. Using a circular drill to create a bone defect with a diameter of 5 mm in the skull bone tissue, the scaffold was implanted, and the skin and intimal tissue on both sides were pulled together to suture. After 4 weeks and 8 weeks following implantation, rats were sacrificed using intraperitoneal injection of anesthesia (30% chloral hydrate). Finally, the scaffolds and skull tissue were removed and immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde for one week.

Micro-CT was used to scan the scaffold and surrounding tissues with a test voltage of 70 kV, a current of 100 μA, a minimum resolution of 22 μm, a rotation step of 0.6°, and a 180° scan. Then, the three-dimensional morphology of the sample was reconstructed, and the percentage of bone formation was calculated (BV/ TV).

After scanning, the samples were immersed in 10% EDTA to decalcify for 4 weeks, and embedded in paraffin for sectioning. The sections were stained with Masson and H&E, as well as immunohistochemical staining for BMP2, OCN, and CD31 (HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit lgG, 1:2000 diluted), and in selected areas with equal area staining the number of new blood vessels was counted.

2.8. Statistical analysis

All experiments were carried out in three parallel experiments, and the data are expressed as mean ± SD. The experimental data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and were compared between groups. When P<0.05, this was defined as significant difference.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration showing the preparation process of PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG 3D-printed scaffolds and the experimental design.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration showing the preparation process of PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG 3D-printed scaffolds and the experimental design.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of MNBG, MgMNBG, and 3D-printed composite scaffolds

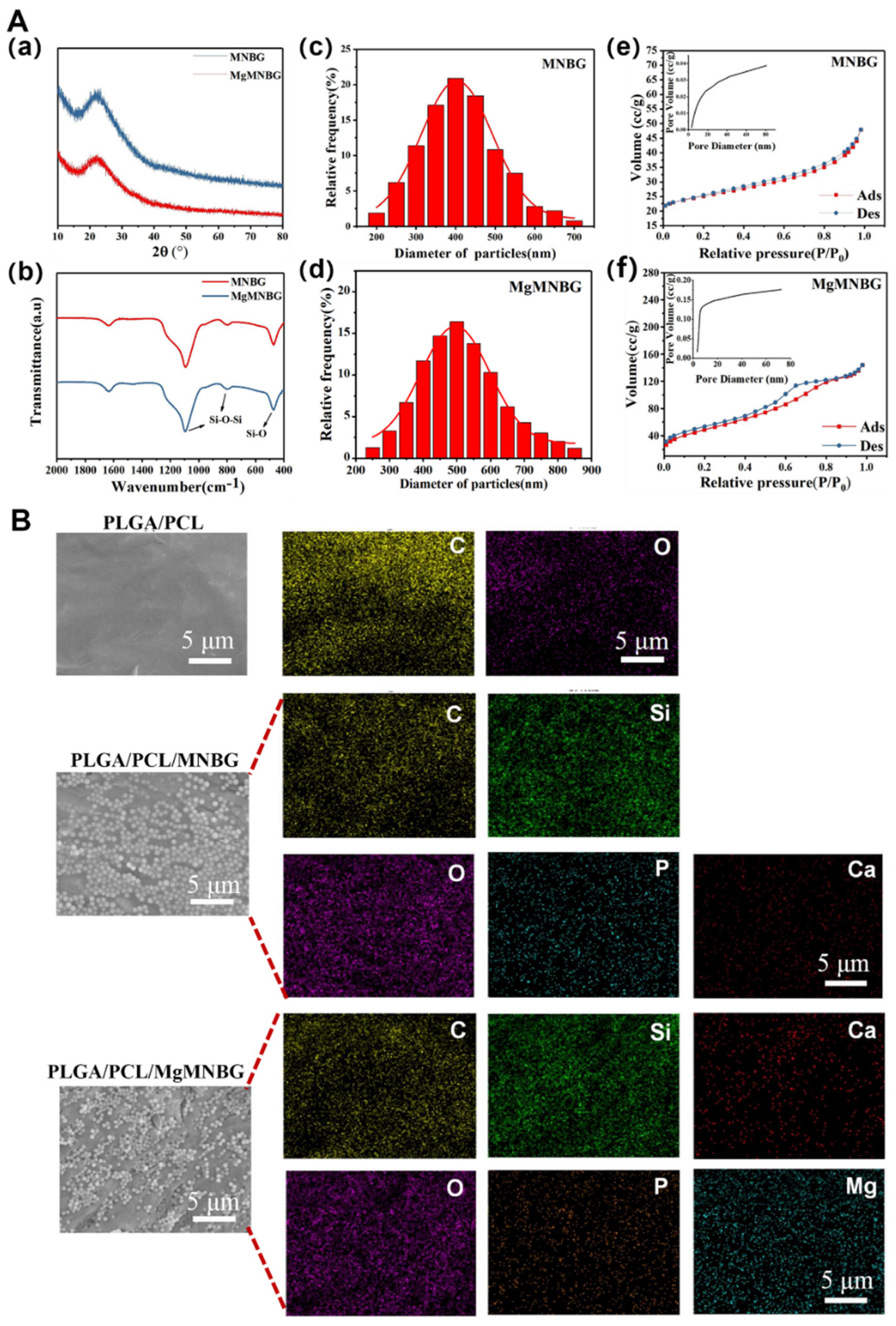

3.1.1. Morphology and particle size distribution of MNBG and MgMNBG

Using the sol–gel method combined with dodecylamine (DDA) as a template and catalyst, micro-nano bioactive glass microspheres with uniform particle size distribution and dispersibility were prepared, namely MNBG (

Figure 2C(a)) and MgMNBG (

Figure 2Cb). Both MgMNBG and MNBG have regular spherical morphologies. In the ethanol/water reaction system, DDA acts as a weak alkaline surfactant and a catalyst to control the hydrolysis–condensation reaction while regulating the hydrolysis of the glass precursor (TEOS) into glass sol. DDA also forms hydrogen bonds between its own hydrophilic amino groups and the formed glass sol, while hydrophobic alkane ends accumulate and synergistically assemble a spherical structure. When TEOS is added slowly, the hydrolysis rate of the system is greater than the polycondensation rate, so a polycondensation reaction occurs in multiple dimensions to form monodisperse micro-nanospheres.

The average particle size of MgMNBG was 480 nm ± 50 nm (

Figure 3Ad), and the average particle size of MNBG was 540 nm ± 50 nm (

Figure 3Ac). The particle size distribution can be fitted using a normal distribution curve. The XRD spectrum shows that MNBG and MgMNBG had dispersion peaks similar to those of bioactive glass (

Figure 2Aa). The infrared spectrum shows that the absorption peaks at wavelengths 1090, 800, and 475 cm

-1 belong to the asymmetric stretching vibration of Si–O –Si (

Figure 2Ab).

3.1.2. Analysis of the surface pore structure of MNBG and MgMNBG

The mesoporous structure of bioactive glass facilitates the release of ions. During the formation of bioactive glass, the heat treatment to remove organic compounds generate pore structures on the surface. The curve in this study was consistent with the type IV adsorption and desorption curve, and the hysteresis loop was type H3, so it had the typical adsorption–desorption characteristics of a mesoporous structure (

Figure 2Ae and Ad). From the pore-size-distribution diagram, the specific surface area of MgMNBG was 109.060 m

2/g and the average pore size was 4.892 nm; the specific surface area of MNBG was 22.324 m

2/g and the average pore size was 3.050 nm. The smaller mesoporous structure of bioglass may have been caused by the slit pores formed by the continuous accumulation of nanoparticles. This indicates that the addition of magnesium ions did not reduce the porosity and specific surface area of micro-nano bioactive glass, but rather improved it.

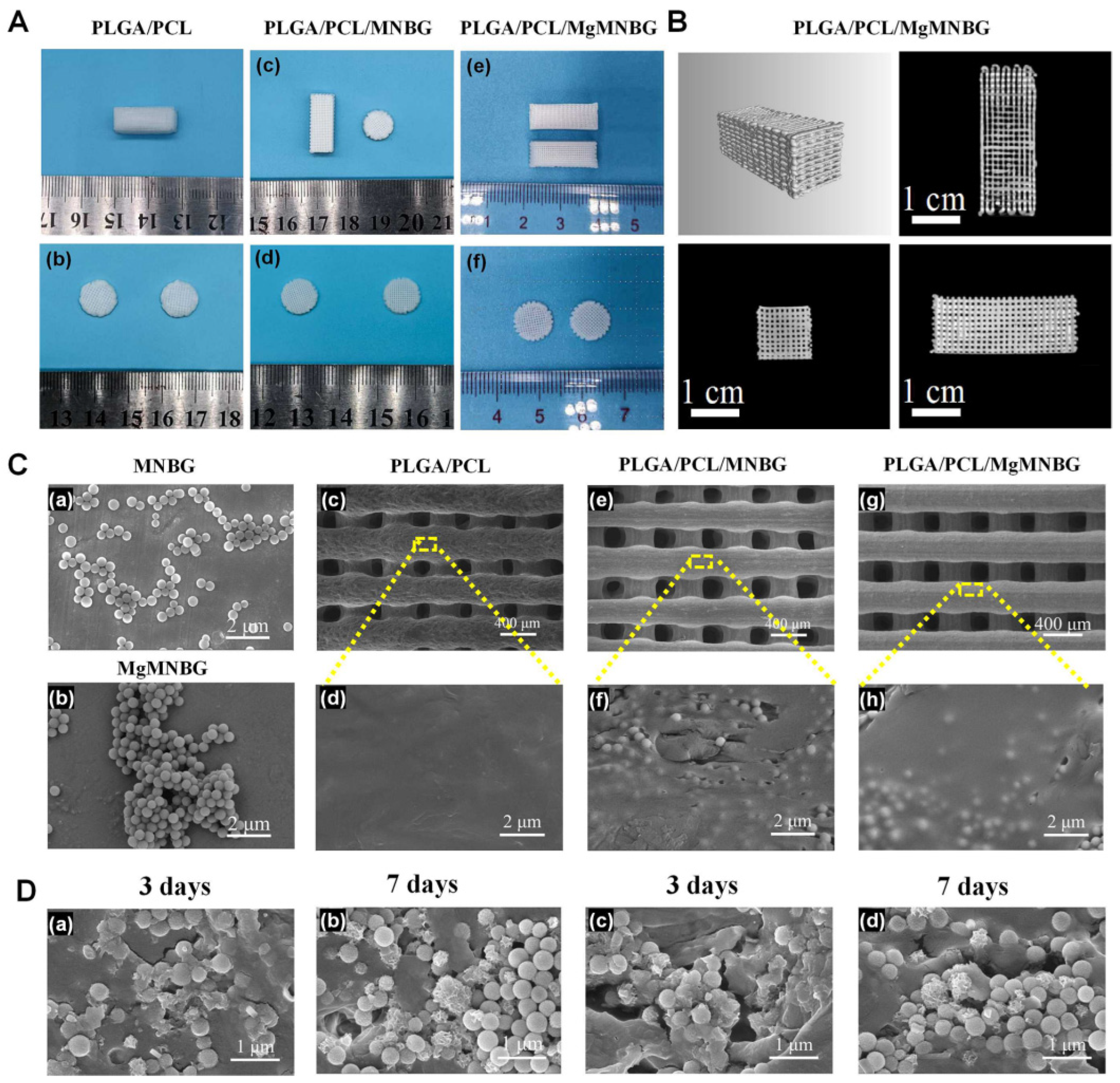

3.1.3. Morphology and energy spectrum analysis of the 3D-printed scaffolds

The 3D-printed scaffold had a good connectivity within the porous structure, with a pore width of about 200–300 μm. Furthermore, the particles were well wrapped in PLGA and PCL (

Figure 3), and the surface of the PLGA/PCL scaffolds was relatively smooth after freeze-drying.

Element distribution on the surface of composite scaffolds indicated that the elements contained in MgMNBG or MNBG were evenly distributed on the surface of the scaffolds. The elemental carbon visible in the energy spectrum is derived from the polymers.

3.1.3. Analysis of mechanical properties

The compressive strength of the PLGA/PCL scaffold was 2.15 Mpa, and the compressive strengths of the PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG and PLGA/PCL/MNBG scaffolds were 4.65 MPa and 4.57 Mpa, respectively. The addition of micro-nano bioactive glass can enhance the hardness and strength of the scaffolds because of its dispersion in the polymer. The binding force between the polymer and particles increases the strength of the scaffolds. The interaction force between the particles also provides mechanical support. Therefore, the addition of MgMNBG or MNBG can improve the mechanical strength of the scaffolds and reduce the risk of brittle fracture of the scaffolds.

3.1.4. In vitro degradation and ion release performance analysis of composite scaffolds

The in vitro degradation of the 3D-printed composite scaffolds was tested (

Figure 4D). During the first 3 days, polymers and bioglass began to degrade, and the weight of scaffolds in each group continued to decrease with the immersion time. However, during days 7–14, the weight loss of the PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG and PLGA/PCL/MNBG scaffolds was slower. The reason for this is that hydroxyapatite deposits were continuously formed on the surface of bioglass in the scaffolds immersed in SBF. The residual weight of the scaffolds after being degraded in SBF was more than 60% after 28 days of degradation. Because of the mineralization of bioglass, PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG and PLGA/PCL/MNBG scaffolds degraded slightly slower than PLGA/PCL scaffolds. The degradation process of PLGA included the gradual transformation of the polylactic acid-glycolic acid into small molecules and their final degradation into lactic acid (

Figure 4F) and water molecules.

The degradation rate of the composite scaffolds for tissue repair needs to match the rate of new bone formation. The composite scaffolds degraded slowly in SBF. As time progressed, MgMNBG or MNBG gradually made contact with the simulated body fluid and the ions were gradually released (

Figure 4G, 4H, 4I). This characteristic has positive significance in the process of implantation and repair.

Mg, Si, and Ca ions can be continuously released in simulated body fluids with the degradation of the scaffold. Magnesium ions can reach 38 ppm after 3 days of cumulative release and over 50 ppm after 7 days of cumulative release, which is conducive to the cell-induction function of magnesium ions (

Figure 4I). The continuous release of silicon and calcium ions is also conducive to new bone regeneration.

3.1.5. Mineralization activity analysis of 3D-printed scaffolds

Hydroxyapatite was formed on the surface composite scaffolds when immersed in SBF (

Figure 3D). The mineralization process of the scaffolds was characterized and analyzed using XRD, and the characteristic peak of hydroxyapatite became stronger as time progressed (

Figure 4A).

The diffraction peaks indicating mineralized HA crystals of PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG and PLGA/PCL/MNBG were detected at 3 days of mineralization, and mineralization reached a higher level at day 7. In the XRD pattern, the characteristic diffraction peaks of HA appear at 26°, 32°, 46°, and 49° in the spectrum, indicating different crystal planes of HA. The form of hydroxyapatite in the process of mineralization has positive significance for the formation of new bone and in combination with new bone tissue.

3.2. Analysis of osteogenesis promoted by scaffolds and their extracts in vitro

3.2.1. Cell viability and proliferation

The scaffolds were seeded with mBMSCs, and the proliferation of the cells was detected using CCK-8 (

Figure 5C). It was shown that cells on the scaffolds proliferated over time. The cell proliferation rate on PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG scaffolds was higher than that on PLGA/PCL/MNBG and PLGA/PCL scaffolds on the fourth and seventh day. This illustrates that the PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG 3D-printed scaffolds have good biocompatibility, which is conducive to the adhesion and growth of cells.

Viability staining of cells in the medium extracts showed that the MgMNBG and MNBG group had faster cell proliferation rate (

Figure 5B). After 4 days of culture, we observed differences between the OD values of the groups. The OD value of the MgMNBG group was higher than that of the MNBG group and also higher than the other groups (

Figure 5C). On the seventh day, MgMNBG showed its stronger ability to promote cell proliferation. Based on the above results, it can be concluded that MgMNBG introduced into the PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG system has the effect of promoting cell proliferation.

3.2.2. ALP activity staining and quantitative analysis

It was shown that the ALP expression of the MNBG and MgMNBG groups was higher than that of the blank group, and the expression level of the MgMNBG group was higher than that of the MNBG group (

Figure 6A). In addition, quantitative analysis results showed a higher ALP activity of cells grown on MgMNBG at 7 days and 14 days compared to the MNBG group and the control group after the same number of days (

Figure 6C). The results were consistent with the staining results, verifying that the MgMNBG group had the highest ALP activity compared to the other groups. The results show that the extract medium of MgMNBG can promote the osteogenic differentiation of mBMSCs.

3.2.3. Analysis of Alizarin Red staining

The plate was stained with alizarin red working solution after 8 days of cultivation (

Figure 6B). The results showed that the mineralized MgMNBG scaffolds had higher calcium content than the MNBG group which in turn had a higher content than the control group. This result objectively demonstrates that MgMNBG has the effect of promoting osteoblast mineralization and osteogenesis.

3.2.4. Expression of osteogenesis-related genes

When mBMSCs cultured with the extract medium containing osteogenic induction for 7 and 14 days, the expression of the ALP, RUNX2, OPN genes in the MgMNBG group was significantly higher than the other groups (

Figure 6D and E). The expression in the MNBG group was also higher than that in the control group. After 14 days of culture, the expression of COL1 and OCN in MgMNBG group was significantly higher than other groups. The higher concentration of the elemental Mg in the MgMNBG extract was conducive to cell proliferation and differentiation, and it showed a stronger ability to promote osteogenic gene expression than the MNBG extract. This indicates that MgMNBG has the strongest ability to promote osteogenic differentiation.

3.3. The Effect of Extracts on Macrophages

3.3.1. Regulation of Macrophage Phenotype by Extracts

When macrophage was cultured in the extracts for 4 days, each group exhibited different levels of CD206 and CD11c expression. The expression levels of CD206 and CD11c in the MNBG group were 49.7% and 43%, the ratio of M2/M1 was 1.42 (

Figure 7A), while the CD206 expression level in the MgMNBG group was higher than in the MNBG group, reaching 61.2%. Furthermore, the ratio of M2/M1 was 1.64, while the M2/M1 ratio in the control group was 0.896. The M2/M1 value in the MgMNBG group was relatively higher, indicating that the overall proportion of M2-type macrophages was highest after cultivation in extract. The reason for this is that the relatively higher concentrations of Mg

2+ and silicate ions released by MgMNBG have a stronger regulatory effect on the phenotype of macrophages, which can promote the differentiation of macrophages into the M2 type.

3.3.2. Expression of macrophage-polarization-related inflammatory genes

Compared to the control group, IL-1β and IL-6 gene expression was downregulated to varying degrees in the MNBG and MgMNBG groups. Among them, MgMNBG showed a more significant upregulation of gene expression of the anti-inflammatory factors IL-1ra, arginase, and IL10. This indicates that the MgMNBG extract polarized towards the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype after four days of cultivation of macrophages (

Figure 7B). Combining this with the results of flow cytometry, it can be concluded that MgMNBG has a good effect in terms of inhibiting the expression of inflammatory genes and promoting the expression of anti-inflammatory genes.

3.3.3. The Effect of Extracts on the Secretion of Bone-Related Factors by Macrophages

Pro-osteogenic related factors BMP-2, VEGF, TGFβ1, and TGFβ3 were used to test the effect of the extract on the regulation of macrophages and the characterization of the mRNA expression levels of genes related to bone regeneration. The results show that the expression of VEGF, BMP2, and TGFβ1 in the MgMNBG group was upregulated with a significant difference. This indicates that the magnesium, silicon, and calcium ions released by MgMNBG have a significant promoting effect on the expression of osteogenic-related factors, which is of great significance for osteogenic differentiation and vascular regeneration during bone repair.

3.4. Analysis of in vitro angiogenesis promoted by the extracts

3.4.1. CD31 immunofluorescence staining and fluorescence quantitative analysis

CD31 immunofluorescence staining was used to evaluate the effect of MgMNBG/ECM and MNBG/ECM extracts on the angiogenesis of HUVECs. The results showed that the positive staining intensity of the MgMNBG group and the MNBG group was higher than that of the control group (

Figure 8A). The results of the quantitative analysis of fluorescence intensity showed that the MgMNBG group was relatively high compared to the MNBG group, and they all had significant differences compared with the control group (

Figure 8B). The above results indicate that the ions in MgMNBG have a stronger ability to promote CD31 expression.

3.4.2. Expression of angiogenesis-related genes

After HUVECs were cultured for 3 days, the gene expression of FGF-2, SDF, and angiogenin in the MgMNBG/ECM or MNBG/ECM extracts was significantly higher than in the control. Compared with the MNBG group, the expression of gene SDF and angiogenin was upregulated in the MgMNBG group (

Figure 8C). Combined with the CD31 fluorescence staining results, it can be concluded that MgMNBG can promote the generation of vascular-related factors to promote angiogenesis.

3.5. In vivo osteogenesis evaluation of 3D-printed composite scaffolds

3.5.1. Micro-CT scanning and quantitative analysis of bone defect repair

The micro-CT results indicate that after 4 and 8 weeks following implantation, new bone had grown between the scaffolds and the original bone tissue (

Figure 9). The implanted scaffolds underwent partial degradation over time. Both the PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG and PLGA/PCL/MNBG groups showed good fusion with the surrounding new bone tissue, and new bone tissue grew around the scaffolds. Additionally, new bone tissue reached the center of the bone defects at 8 weeks. In particular, there was more new bone growth in the central area of the bone defect observed in the PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG group compared to the other groups. This finding suggests that PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG is beneficial for the formation of new bone and provides better conditions for the migration and proliferation of osteoblasts.

This study found that the PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG scaffolds showed significantly more new bone tissue growth, compared to PLGA/PCL/MNBG, PLGA/PCL, and the control. Quantitative analysis of BV/TV confirmed this trend (

Figure 9B). Even the PLGA/PCL scaffolds showed more new bone tissue growth than the control, possibly due to the scaffold providing a medium for osteoblast migration. The results suggest that MgMNBG has high biological activity and promotes bone tissue repair when used in scaffolds for implantation.

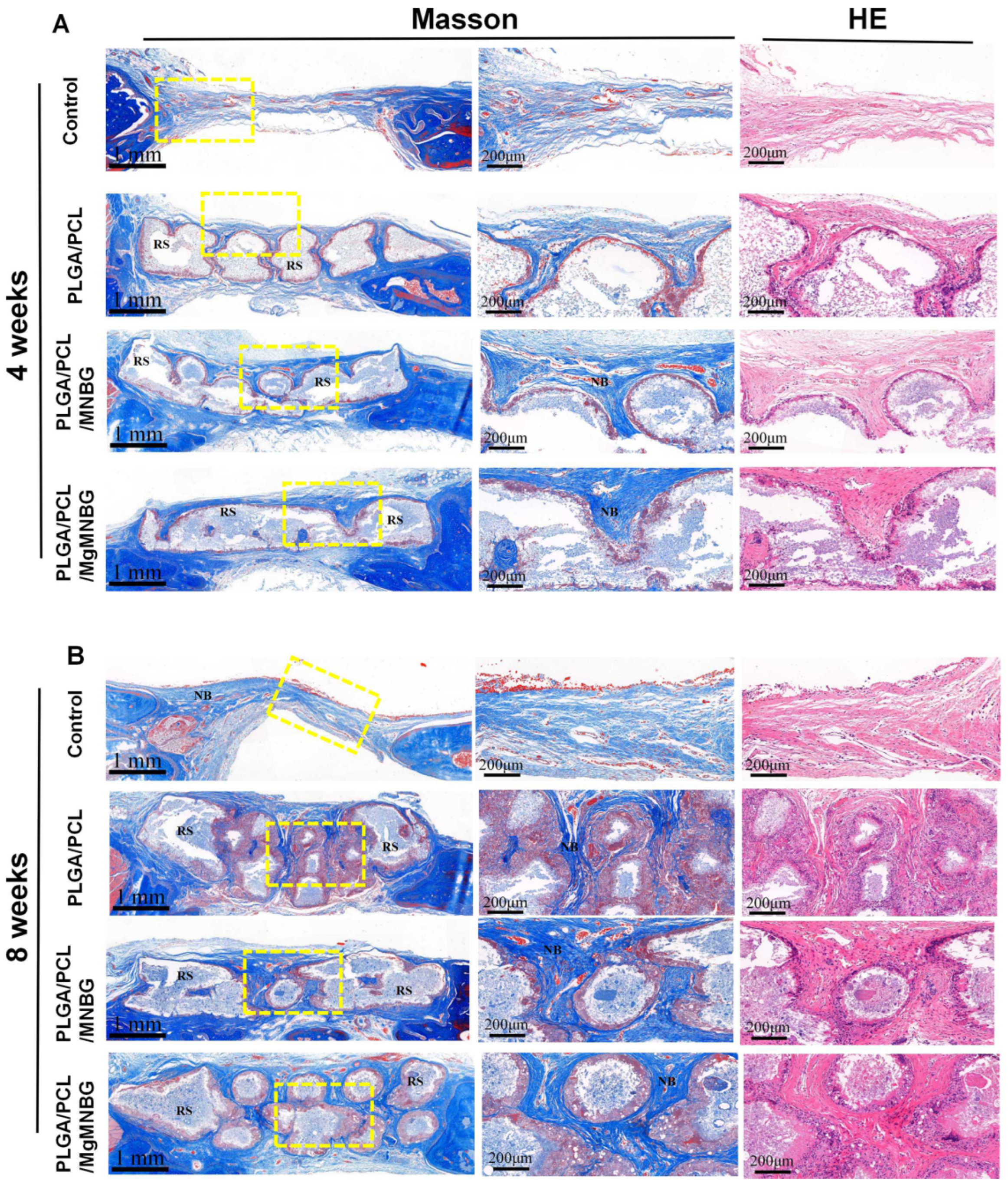

3.5.2. H&E and Masson’s trichrome staining of tissue sections

At four weeks, H&E and Masson’s trichrome staining showed that new bone grew from the edge of the host bone toward the center of the bone defect. Among them, the PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG and PLGA/PCL/MNBG group showed more obvious manifestations. At 8 weeks, more new bone formation appeared in the implanted skull defect center of the PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG group and the PLGA/PCL/MNBG group. This indicates that pro-osteoblasts gradually migrated to the center of the defect site to proliferate and differentiate to form new bone with the prolongation of implantation time. However, in the blank group, new bone was formed only at the scaffold borders, near the original bone tissue. These results also directly indicate that the PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG scaffolds were more beneficial to the migration and proliferation of osteoblasts.

Figure 10.

Masson’s trichrome and H&E staining of the implanted scaffolds and the bone tissue surrounding the skull defect; (A) staining of tissue sections after 4 weeks following implantation; (B) staining of tissue sections after eight weeks following implantation. RS: residual scaffold; NB: new bone.

Figure 10.

Masson’s trichrome and H&E staining of the implanted scaffolds and the bone tissue surrounding the skull defect; (A) staining of tissue sections after 4 weeks following implantation; (B) staining of tissue sections after eight weeks following implantation. RS: residual scaffold; NB: new bone.

3.5.3. CD31 immunohistochemical staining

Staining was carried out to evaluate the effect of scaffolds on the promotion of early angiogenesis in bone repair during the first 4 weeks. The PLGA/PCL/MNBG and PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG groups showed positive expression of CD31 (

Figure 11A). The positive expression was more obvious than in the control. This phenomenon showed that the PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG group had a certain promoting effect on the expression of CD31, and this result is consistent with the results from the in vitro experiments (

Figure 8). Quantitative calculation of blood vessel numbers also revealed that the PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG group had significantly more neovascularization than other groups (

Figure 11B). This phenomenon can be attributed to the existence of MgMNBG in the PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG scaffold, which promotes vascular regeneration by releasing Mg

2+ and silicon ions. Based on the above results, it can be concluded that both MgMNBG and PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG scaffolds have stronger angiogenic effects compared to other materials tested.

3.5.4. OCN and BMP2 immunohistochemical staining

The result shows that PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG and PLGA/PCL/MNBG group were positive in (expression of BMP2 and OCN, and the positive staining intensities of BMP2 and OCN wer

e higher in this group than in the PLGA/PCL group and the control (

Figure 11C). In the experimental group, the part of the scaffolds about to be degraded in the periphery was strongly stained. This phenomenon can be explained by the impending formation of new bone near the degrading part of the scaffold, and the ions released during the scaffold degradation can promote the expression of osteogenic genes. The results indicate that PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG scaffolds can promote the expression of BMP2 and OCN proteins.

Quantitative statistics of the total number of blood vessels in selected areas with equal cross-sectional area at four weeks; (C) BMP2 Immunohistochemical staining at 4 weeks and 8 weeks after implantation of the composite scaffolds; (D) OCN immunohistochemical staining at 4 weeks and 8 weeks after implantation of the composite scaffolds.

4. Discussion

The presence of magnesium ions is indispensable in the repair process of bone defects, and studies have shown that magnesium can play an important role in early bone repair. It can affect the differentiation of bone-marrow mesenchymal stem cells through the production of pro-osteogenic factors by macrophages. In the late stage of bone healing, macrophages induced by magnesium ions can secrete anti-inflammatory and osteogenic factors, promoting bone tissue regeneration. The influx of Mg

2+ regulates immunity through TRPM7 and M7CKs channels, promoting recruitment and differentiation of bone-marrow mesenchymal stem cells [

38,

39]. Some studies have shown that adding magnesium to calcium phosphate [

40,

41] or alloys [

42] can downregulate the expression of macrophage inflammatory genes and promote the expression of osteogenic factors.

In in vitro experiments, the culture medium contained 0.8 mM of Mg2+. After preparing the extract of MgMNBG, concentrations of Mg2+ and silicon ions were significantly increased, which is the key to promoting the expression of osteogenic-related genes and regulating macrophage polarization in in vitro experiments. In our in vitro experiments, we also observed that extracts of MgMNBG can effectively downregulate the expression of macrophage inflammatory genes (IL6, IL1β) and promote the expression of osteogenic-related factors (VEGF, BMP2, TGFβ1), thus promoting differentiation of bone-marrow mesenchymal stem cells and angiogenesis. In addition, the silicon and calcium ions released by MgMNBG also have the function of promoting osteogenesis, which was verified in the proliferation and differentiation experiments of mBMSCs cultured in vitro. When HUVECs were cultured in the extracts, it was revealed that MgMNBG can promote the expression of angiogenesis related genes.

It was verified that MgMNBG has the function of promoting the proliferation and differentiation of osteoblasts, and it can also promote the expression of related osteogenic genes. Furthermore, it showed a positive regulatory effect on the expression of osteogenic calcified nodules. The extract of MgMNBG can regulate the differentiation of macrophages into the M2 type and promote the expression of anti-inflammatory factors and bone-related factors, which play an important role in promoting bone regeneration and defect repair.

The 3D-printed scaffolds consisted of PLGA and PCL as the carrier and, combined with MgMNBG with osteogenic activity, they were verified to have good biocompatibility in experiments. The excellent bioactivity of the micro-nano bioactive glass can enhance the biological activity of 3D-printed scaffolds. PLGA and PCL have good biocompatibility and degradability, and the degradation products can be metabolized in the body and excreted. The scaffolds were tested in simulated body fluid to demonstrate that the release concentration of magnesium ions can reach a concentration conducive to osteogenesis. Ca, Si, and Mg ions released by MgMNBG can not only neutralize the pH reduction caused by the degradation of PLGA, which produces lactic acid, but also promote the regeneration and differentiation of bone-marrow mesenchymal stem cells.

The in vivo bone-defect-repair experiment using the scaffolds showed that the bone-repair performance of the PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG group was better than the other groups at 4 weeks and 8 weeks. One of the reasons for this is that the introduction of Mg2+ has a certain promoting effect on early angiogenesis in the bone repair area. The results were consistent with the quantitative analysis of CD31 staining and the number of blood vessels in in vivo experiments. Moreover, magnesium, along with silicon and calcium ions, can better promote osteogenic differentiation, which is confirmed by the results of the in vitro experiments.

Mg2+ mainly plays a role in the early stages of osteogenesis, and the excessive concentration of magnesium may lead to NF-κ B signal transduction, which can easily inhibit bone repair in the later stage; consequently, it is necessary to control the concentration of magnesium ions. In this study, the introduction of a certain amount of elemental magnesium in the MgMNBG and PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG composite scaffolds ensures that its release concentration is not too high and that its sustained release is within a safe concentration range.

The in vitro and in vivo experimental results indicate that the PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG scaffolds not only have good biodegradability and biocompatibility, but also excellent functions in promoting bone-defect regeneration and repair. The scaffolds can release the functional ions Mg, Si, and Ca through degradation of MgMNBG to regulate the secretion of osteogenic-related factors by macrophages as well as promoting osteogenic differentiation and vascular regeneration, and thus they have better bone repair effects than the other tested groups.

5. Conclusions

In summary, MgMNBG can promote the secretion of osteogenic-related factors through immune regulation. The released Mg, Si, and Ca ions have the effect of promoting osteogenesis and angiogenesis. The 3D-printed PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG composite scaffolds have good degradability and biological activity, high pro-osteogenic properties, and promote angiogenesis. Therefore, they have potential in medical applications.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through the contribution of all authors. All authors have given approval of the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFC110630), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. U1501245, 51672088, 32000943), the Beijing Municipal Health Commission (Grant No. BMHC-2019-9 and BMHC-2018-4; PXM2020_026275_000002)

References

- García-Gareta, Elena, Melanie J. Coathup, and Gordon W. Blunn. “Osteoinduction of Bone Grafting Materials for Bone Repair and Regeneration.” Bone 81 (2015): 112-21. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Ying, Adrian D. Juncos Bombin, Peter Boyd, Nicholas Dunne, and Helen O. McCarthy. “Application of 3d Printing & 3d Bioprinting for Promoting Cutaneous Wound Regeneration.” Bioprinting 28 (2022): e00230. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Chong, Wei Huang, Yu Zhou, Libing He, Zhi He, Ziling Chen, Xiao He, Shuo Tian, Jiaming Liao, Bingheng Lu, Yen Wei, and Min Wang. “3d Printing of Bone Tissue Engineering Scaffolds.” Bioactive Materials 5, no. 1 (2020): 82-91. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, R., and A. H. Reddi. “Influence of Magnesium Depletion on Matrix-Induced Endochondral Bone Formation.” Calcified Tissue International 29, no. 1 (1979): 15-20. [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, J., W. Godden, and M. M. Warnock. “The Effect of Acute Magnesium Deficiency on Bone Formation in Rats.” Biochemical Journal 34, no. 1 (1940): 97. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W., S. Guo, Z. Tang, X. Wei, and Z. Guo. “Magnesium Promotes Bone Formation and Angiogenesis by Enhancing Mc3t3-E1 Secretion of Pdgf-Bb.” Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 528, no. 4 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Su, Yingchao, Matthew Cappock, Stephanie Dobres, Allan J. Kucine, Wayne C. Waltzer, and Donghui Zhu. “Supplemental Mineral Ions for Bone Regeneration and Osteoporosis Treatment.” Engineered Regeneration 4, no. 2 (2023): 170-82. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Jie, Junfeng Jia, Fan Wu, Shicheng Wei, Huanjun Zhou, Hongbo Zhang, Jung-Woog Shin, and Changsheng Liu. “Hierarchically Microporous/Macroporous Scaffold of Magnesium–Calcium Phosphate for Bone Tissue Regeneration.” Biomaterials 31, no. 6 (2010): 1260-69. [CrossRef]

- Gallo, Marta, Bastien Le Gars Santoni, Thierry Douillard, Fei Zhang, Laurent Gremillard, Silvia Dolder, Willy Hofstetter, Sylvain Meille, Marc Bohner, Jérôme Chevalier, and Solène Tadier. “Effect of Grain Orientation and Magnesium Doping on Β-Tricalcium Phosphate Resorption Behavior.” Acta Biomaterialia 89 (2019): 391-402. [CrossRef]

- Hou, Yuxi, Ran Zhang, Huaiyi Cheng, Yue Wang, Qingmei Zhang, Lupeng Zhang, Lu Wang, Ran Li, Xiuping Wu, and Bing Li. “Mg2+-Doped Carbon Dots Synthesized Based on Lycium Ruthenicum in Cell Imaging and Promoting Osteogenic Differentiation in Vitro.” Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 656 (2023): 130264. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Hang, Bing Liang, Haitao Jiang, Zhongliang Deng, and Kexiao Yu. “Magnesium-Based Biomaterials as Emerging Agents for Bone Repair and Regeneration: From Mechanism to Application.” Journal of Magnesium and Alloys 9, no. 3 (2021): 779-804. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Ning, Shude Yang, Huixin Shi, Yiping Song, Hui Sun, Qiang Wang, Lili Tan, and Shu Guo. “Magnesium Alloys for Orthopedic Applications:A Review on the Mechanisms Driving Bone Healing.” Journal of Magnesium and Alloys 10, no. 12 (2022): 3327-53. [CrossRef]

- Li, R., A. E. Clark, and L. L. Hench. “An Investigation of Bioactive Glass Powders by Sol-Gel Processing.” Journal of Applied Biomaterials 2, no. 4 (2010): 231-39. [CrossRef]

- Hench, L. L. “Genetic Design of Bioactive Glass.” Journal of the European Ceramic Society 29, no. 7 (2009): 1257-65. [CrossRef]

- Miao, Guohou, Zhengmao Li, Yongchun Meng, Jingwen Wu, Yuli Li, Qing Hu, Xiaofeng Chen, Xuechao Yang, and Xiaoming Chen. “Preparation, Characterization, in Vitro Bioactivity and Protein Loading/Release Property of Mesoporous Bioactive Glass Microspheres with Different Compositions.” Advanced Powder Technology 30, no. 9 (2019): 1848-57. [CrossRef]

- Zeimaran, E., S. Pourshahrestani, I. Djordjevic, B. Pingguan-Murphy, N. A. Kadri, and M. R. Towler. “Bioactive Glass Reinforced Elastomer Composites for Skeletal Regeneration: A Review.” Materials Science & Engineering C 53, no. aug. (2015): 175-88. [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, M., K. Kavitha, P. Manivasakan, V. Rajendran, and P. Kulandaivelu. “Synthesis, Characterization and Biological Response of Magnesium-Substituted Nanobioactive Glass Particles for Biomedical Applications.” Ceramics International 39, no. 2 (2013): 1683-94. [CrossRef]

- Boccaccini, A. R., M. Erol, W. J. Stark, D. Mohn, Z. Hong, and J. F. Mano. “Polymer/Bioactive Glass Nanocomposites for Biomedical Applications: A Review.” Composites Science & Technology 70, no. 13 (2010): 1764-76. [CrossRef]

- Peter, M., N. S. Binulal, S. V. Nair, N. Selvamurugan, H. Tamura, and R. Jayakumar. “Novel Biodegradable Chitosan–Gelatin/Nano-Bioactive Glass Ceramic Composite Scaffolds for Alveolar Bone Tissue Engineering.” Chemical Engineering Journal 158, no. 2 (2010): 353-61. [CrossRef]

- Park, Soyeon, Wan Shou, Liane Makatura, Wojciech Matusik, and Kun Fu. “3d Printing of Polymer Composites: Materials, Processes, and Applications.” Matter 5, no. 1 (2022): 43-76. [CrossRef]

- Bekas, D. G., Y. Hou, Y. Liu, and A. Panesar. “3d Printing to Enable Multifunctionality in Polymer-Based Composites: A Review.” Composites Part B: Engineering 179 (2019): 107540. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Lei, Guojing Yang, Blake N. Johnson, and Xiaofeng Jia. “Three-Dimensional (3d) Printed Scaffold and Material Selection for Bone Repair.” Acta Biomaterialia 84 (2019): 16-33. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, Gurbinder, Vishal Kumar, Francesco Baino, John C. Mauro, Gary Pickrell, Iain Evans, and Oana Bretcanu. “Mechanical Properties of Bioactive Glasses, Ceramics, Glass-Ceramics and Composites: State-of-the-Art Review and Future Challenges.” Materials Science and Engineering: C 104 (2019): 109895. [CrossRef]

- Dziadek, M., J. Pawlik, E. Menaszek, E. Stodolak-Zych, and K. Cholewa-Kowalska. “Effect of the Preparation Methods on Architecture, Crystallinity, Hydrolytic Degradation, Bioactivity, and Biocompatibility of Pcl/Bioglass Composite Scaffolds.” J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater (2015): 1580-93. [CrossRef]

- Zimmerling, A., Z. Yazdanpanah, Dml Cooper, J. D. Johnston, and X. Chen. “3d Printing Pcl/Nha Bone Scaffolds: Exploring the Influence of Material Synthesis Techniques.” Biomaterials Research 25 (2021): 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Peng, C., J. Zheng, D Chen, X. Zhang, L. Deng, Z. Chen, and L. Wu. “Response of Hpdlscs on 3d Printed Pcl/Plga Composite Scaffolds Invitro.” Molecular Medicine Reports 18 (2018): 1335-44. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J., C. Z. Chen, D. G. Wang, and J. H. Hu. “Synthesis, Characterization and in Vitro Bioactivity of Magnesium-Doped Sol–Gel Glass and Glass-Ceramics.” Ceramics International 37, no. 5 (2011): 1637-44. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Ting, Timothy R. Holzberg, Casey G. Lim, Feng Gao, Ankit Gargava, Jordan E. Trachtenberg, Antonios G. Mikos, and John P. Fisher. “3d Printing Plga: A Quantitative Examination of the Effects of Polymer Composition and Printing Parameters on Print Resolution.” Biofabrication, no. 2 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Penumakala, Pavan Kumar, Jose Santo, and Alen Thomas. “A Critical Review on the Fused Deposition Modeling of Thermoplastic Polymer Composites.” Composites Part B: Engineering 201 (2020): 108336. [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y., L. Li, S. Chen, M. Zhang, X. Wang, P. Zhang, and L. Qin. “A Novel Magnesium Composed Plga/Tcp Porous Scaffold Fabricated by 3d Printing for Bone Regeneration.” Journal of Orthopaedic Translation 2, no. 4 (2014): 218-19. [CrossRef]

- B, Yuxiao Lai A, Ye Li A C, Huijuan Cao A, Jing Long A, Xinluan Wang A C, Long Li A, Cairong Li A, Qingyun Jia A, Bin Teng A, and Tingting Tang D. “Osteogenic Magnesium Incorporated into Plga/Tcp Porous Scaffold by 3d Printing for Repairing Challenging Bone Defect.” Biomaterials 197 (2019): 207-19. [CrossRef]

- Eqtesadi, S., A. Motealleh, A. Pajares, F. Guiberteau, and P. Miranda. “Influence of Sintering Temperature on the Mechanical Properties of -Pcl-Impregnated 45s5 Bioglass-Derived Scaffolds Fabricated by Robocasting.” Journal of the European Ceramic Society (2015): 3985-93. [CrossRef]

- Motealleh, A., S. Eqtesadi, F. H. Perera, A. Pajares, F. Guiberteau, and P. Miranda. “Understanding the Role of Dip-Coating Process Parameters in the Mechanical Performance of Polymer-Coated Bioglass Robocast Scaffolds.” Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials 64 (2016): 253-61. [CrossRef]

- Khodaei, Mohammad, Farahnaz Nejatidanesh, Mohammad Javad Shirani, Alireza Valanezhad, Ikuya Watanabe, and Omid Savabi. “The Effect of the Nano- Bioglass Reinforcement on Magnesium Based Composite.” Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials 100 (2019): 103396. [CrossRef]

- Ribas, Renata Guimarães, Vanessa Modelski Schatkoski, Thaís Larissa do Amaral Montanheiro, Beatriz Rossi Canuto de Menezes, Cristiane Stegemann, Douglas Marcel Gonçalves Leite, and Gilmar Patrocínio Thim. “Current Advances in Bone Tissue Engineering Concerning Ceramic and Bioglass Scaffolds: A Review.” Ceramics International 45, no. 17, Part A (2019): 21051-61. [CrossRef]

- Miguez-Pacheco, Valentina, Larry L. Hench, and Aldo R. Boccaccini. “Bioactive Glasses Beyond Bone and Teeth: Emerging Applications in Contact with Soft Tissues.” Acta Biomaterialia 13 (2015): 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Li, Peiyi, Yanfei Li, Tszyung Kwok, Tao Yang, Cong Liu, Weichang Li, and Xinchun Zhang. “A Bi-Layered Membrane with Micro-Nano Bioactive Glass for Guided Bone Regeneration.” Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 205 (2021): 111886. [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Wei, Karen H. M. Wong, Jie Shen, Wenhao Wang, Jun Wu, Jinhua Li, Zhengjie Lin, Zetao Chen, Jukka P. Matinlinna, Yufeng Zheng, Shuilin Wu, Xuanyong Liu, Keng Po Lai, Zhuofan Chen, Yun Wah Lam, Kenneth M. C. Cheung, and Kelvin W. K. Yeung. “Trpm7 Kinase-Mediated Immunomodulation in Macrophage Plays a Central Role in Magnesium Ion-Induced Bone Regeneration.” Nature Communications 12, no. 1 (2021): 2885. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Luxin, Deye Song, Kai Wu, Zhengxiao Ouyang, Qianli Huang, Guanghua Lei, Kun Zhou, Jian Xiao, and Hong Wu. “Sequential Activation of M1 and M2 Phenotypes in Macrophages by Mg Degradation from Ti-Mg Alloy for Enhanced Osteogenesis.” Biomaterials Research 26, no. 1 (2022): 17. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Meng, Yuanman Yu, Kai Dai, Zhengyu Ma, Yang Liu, Jing Wang, and Changsheng Liu. “Improved Osteogenesis and Angiogenesis of Magnesium-Doped Calcium Phosphate Cement Via Macrophage Immunomodulation.” Biomaterials Science 4, no. 11 (2016): 1574-83. [CrossRef]

- Qi, Dahu, Jin Su, Song Li, Hao Zhu, Lijin Cheng, Shuaibin Hua, Xi Yuan, Jiawei Jiang, Zixing Shu, Yusheng Shi, and Jun Xiao. “3d Printed Magnesium-Doped Β-Tcp Gyroid Scaffold with Osteogenesis, Angiogenesis, Immunomodulation Properties and Bone Regeneration Capability in Vivo.” Biomaterials Advances 136 (2022): 212759. [CrossRef]

- Li, Bin, Yan Hu, Yaochao Zhao, Mengqi Cheng, Hui Qin, Tao Cheng, Qiaojie Wang, Xiaochun Peng, and Xianlong Zhang. “Curcumin Attenuates Titanium Particle-Induced Inflammation by Regulating Macrophage Polarization in Vitro and in Vivo≪/I&Gt.” Frontiers in immunology (2017). [CrossRef]

Figure 2.

Characterization of MNBG and MgMNBG, surface energy spectra of the scaffolds. A(a) XRD spectra of MNBG and MgMNBG; (Ab) FTIR spectra of MNBG and MgMNBG; (Ac),(Ad) Particle size distribution of MNBG and MgMNBG; (Af),(Ae) pore distribution of MNBG and MgMNBG particles. (B) Surface energy spectra of the composite scaffolds.

Figure 2.

Characterization of MNBG and MgMNBG, surface energy spectra of the scaffolds. A(a) XRD spectra of MNBG and MgMNBG; (Ab) FTIR spectra of MNBG and MgMNBG; (Ac),(Ad) Particle size distribution of MNBG and MgMNBG; (Af),(Ae) pore distribution of MNBG and MgMNBG particles. (B) Surface energy spectra of the composite scaffolds.

Figure 3.

Morphological characterization and depiction of mineralization of 3D-printed composite scaffolds: (A) Representative digital photos of PLGA/PCL, PLGA/PCL/MNBG, and PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG scaffolds. (B) CT three-dimensional scanning of a PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG scaffold. (Ca) Morphology of MNBG; (Cb) morphology of MgMNBG; (Cc),(Cd) SEM surface morphology of a PLGA/PCL scaffold; (Ce),(Cf) SEM surface morphology of a PLGA/PCL/MNBG scaffold; (Cg),(Ch) SEM surface morphology of a PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG scaffold. (Da),(Db) Surface morphology of a PLGA/PCL/MNBG scaffold after mineralization in SBF for 3 or 7 days; (Dc),(Dd) surface morphology of PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG scaffold after mineralization in SBF for 3 or 7 days.

Figure 3.

Morphological characterization and depiction of mineralization of 3D-printed composite scaffolds: (A) Representative digital photos of PLGA/PCL, PLGA/PCL/MNBG, and PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG scaffolds. (B) CT three-dimensional scanning of a PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG scaffold. (Ca) Morphology of MNBG; (Cb) morphology of MgMNBG; (Cc),(Cd) SEM surface morphology of a PLGA/PCL scaffold; (Ce),(Cf) SEM surface morphology of a PLGA/PCL/MNBG scaffold; (Cg),(Ch) SEM surface morphology of a PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG scaffold. (Da),(Db) Surface morphology of a PLGA/PCL/MNBG scaffold after mineralization in SBF for 3 or 7 days; (Dc),(Dd) surface morphology of PLGA/PCL/MgMNBG scaffold after mineralization in SBF for 3 or 7 days.

Figure 4.

Physicochemical properties of 3D-printed composite scaffolds; (A) XRD patterns of the composite scaffolds mineralized in SBF solution for 3 and 7 days; (B) pH change during the degradation of composite scaffolds in SBF; (C) remaining weight of scaffolds during degradation; (D) mechanical strength of the scaffolds; (E) porosity of the composite scaffolds; (F) lactic acid concentration during degradation in SBF; (G),(H),(I) ion release curves during the degradation process of the composite scaffolds.

Figure 4.

Physicochemical properties of 3D-printed composite scaffolds; (A) XRD patterns of the composite scaffolds mineralized in SBF solution for 3 and 7 days; (B) pH change during the degradation of composite scaffolds in SBF; (C) remaining weight of scaffolds during degradation; (D) mechanical strength of the scaffolds; (E) porosity of the composite scaffolds; (F) lactic acid concentration during degradation in SBF; (G),(H),(I) ion release curves during the degradation process of the composite scaffolds.

Figure 5.

Adhesion and proliferation of mBMSCs: (A) live–dead staining of cells cultured in extract media for 1, 4, and 7 days; (B) cell proliferation of mBMSCs cultured in extracts for 1, 4, and 7 days. * P <0.05 vs. control group; # P <0.05 vs. MNBG group. (C) the proliferation of cells on scaffolds for 1, 4, and 7 days, * P <0.05 vs. control group; # P <0.05 vs. PLGA/PCL/MNBG group.

Figure 5.

Adhesion and proliferation of mBMSCs: (A) live–dead staining of cells cultured in extract media for 1, 4, and 7 days; (B) cell proliferation of mBMSCs cultured in extracts for 1, 4, and 7 days. * P <0.05 vs. control group; # P <0.05 vs. MNBG group. (C) the proliferation of cells on scaffolds for 1, 4, and 7 days, * P <0.05 vs. control group; # P <0.05 vs. PLGA/PCL/MNBG group.

Figure 6.

Effects on osteogenic differentiation of mBMSCs cultured for 7 days and 14 days; (A) alkaline phosphatase staining of mBMSCs cultured in extracts for 7 days; (B) alizarin red staining of mBMSCs cultured in extracts for 8 days; (C) ALP quantification of mBMSCs cultured in extracts for 7 and 14 days; (D) expression of osteogenic genes (ALP, OCN, OPN, COL1, RUNX2) at 7 and 14 days. * P <0.05 vs. control group; # P <0.05 vs. MNBG group. .

Figure 6.

Effects on osteogenic differentiation of mBMSCs cultured for 7 days and 14 days; (A) alkaline phosphatase staining of mBMSCs cultured in extracts for 7 days; (B) alizarin red staining of mBMSCs cultured in extracts for 8 days; (C) ALP quantification of mBMSCs cultured in extracts for 7 and 14 days; (D) expression of osteogenic genes (ALP, OCN, OPN, COL1, RUNX2) at 7 and 14 days. * P <0.05 vs. control group; # P <0.05 vs. MNBG group. .

Figure 7.

(A) FACS test results of RAW 264.7 cells cultured in the extracts for 4 days; (B) expression of pro-inflammatory related genes in macrophages cultured in the extracts for 4 days; (C) expression of anti-inflammatory related genes in macrophages cultured in the extracts for 4 days; (D) expression of osteogenic-related genes in RAW 264.7 cells cultured in the extracts for 4 days.

Figure 7.

(A) FACS test results of RAW 264.7 cells cultured in the extracts for 4 days; (B) expression of pro-inflammatory related genes in macrophages cultured in the extracts for 4 days; (C) expression of anti-inflammatory related genes in macrophages cultured in the extracts for 4 days; (D) expression of osteogenic-related genes in RAW 264.7 cells cultured in the extracts for 4 days.

Figure 8.

In vitro angiogenesis performance test of HUVECs cultured in control, MNBG/ECM, and MgMNBG/ECM. (A) CD31 immunofluorescence staining (CD31 staining depicted in green, DAPI in blue); (B) quantitative analysis of immunofluorescence staining; (C) expression of SDF, FGF-2, and angiogenin after 3 days of culture. * P <0.05 vs. control group, # P <0.05 vs. MNBG group. .

Figure 8.

In vitro angiogenesis performance test of HUVECs cultured in control, MNBG/ECM, and MgMNBG/ECM. (A) CD31 immunofluorescence staining (CD31 staining depicted in green, DAPI in blue); (B) quantitative analysis of immunofluorescence staining; (C) expression of SDF, FGF-2, and angiogenin after 3 days of culture. * P <0.05 vs. control group, # P <0.05 vs. MNBG group. .

Figure 9.

Implantation of 3D-printed composite scaffolds for repairing bone defects; (A) implantation of scaffolds in skull defects; (B) BV/TV values of the implanted portion of the defect 4 and 8 weeks after implanted into the defect; (C) micro-CT scanning analysis of skull defects and new bone formation after 4 and 8 weeks following implantation.

Figure 9.

Implantation of 3D-printed composite scaffolds for repairing bone defects; (A) implantation of scaffolds in skull defects; (B) BV/TV values of the implanted portion of the defect 4 and 8 weeks after implanted into the defect; (C) micro-CT scanning analysis of skull defects and new bone formation after 4 and 8 weeks following implantation.

Figure 11.

Immunohistochemical staining of the implanted scaffolds and the bone tissue: (A) CD31 immunohistochemical staining at 4 weeks after implantation of the composite scaffolds; (B).

Figure 11.

Immunohistochemical staining of the implanted scaffolds and the bone tissue: (A) CD31 immunohistochemical staining at 4 weeks after implantation of the composite scaffolds; (B).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).