1. Introduction

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) affects 14% of all pregnancies globally [

1], and is the most common complication in pregnancy [

2]. In Denmark, 6% of all pregnancies are affected by GDM [

3]. Although usually a transient condition, GDM is associated with an increased risk of short- and long-term adverse health outcomes in both the women and their offspring [

1,

4]. Also, the risk of recurrent GDM is high, ranging between 30-84% [

5]. In the longterm, women with prior GDM and their offspring are at an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes (T2D) [

6,

7,

8] and BMI remains the main modifiable risk factor for T2D development among women with prior GDM [

9]. Structured interventions targeting weight loss have shown that reducing T2D risk is possible through changes in diet and physical activity in this group of women [

10,

11]. Also, persistent changes in diet and physical activity have been found to uphold T2D risk reduction after 10 years among women with prior GDM [

12]. Still, it remains unclear how health behaviors can be sustained in the long-term [

13]. According to a meta-analysis of interventions applying self-determination theory, some types of motivation increase the likelihood of sustained behavior change across target populations and behaviors [

14]. Thus, motivation is most likely an active mechanism in seeking to explain maintenance of healthy behavior [

15]. Identifying such mechanisms of change is essential to understand how intervention effects have occurred and how an intervention may be replicated in other settings [

16]. Thus, investigating motivation as an assumed mechanism for health behavior change in the Face-it intervention is important to understand how prevention efforts targeting T2D risk may be improved.

Many qualitative studies have shown that social support from a partner is a key motivational factor for improving health behaviors among women with prior GDM [

17], even in the Danish context [

18]. Still, few interventions have focused on the family setting, which may explain the limited success of interventions to demonstrate long-term behavior change. Few interventions have involved women with GDM and their partners [

19,

20]. McManus et al. showed that when these women and their partners participated together, women’s retention in the intervention increased, and when their partners lost weight, the women’s weight tended to follow [

19]. Furthermore, Brazeau and colleagues documented that physical activity levels increased in both women with prior GDM and their partners after engaging in an intervention including mutual physical activity and meal sessions [

20]. For both interventions, retention among couples remained high [

19,

20]. Couples often share daily routines in the household and health behaviors which most likely results in them influencing each other’s health status [

21,

22]. This may explain why partners of women with prior GDM have also been found to be at increased risk of T2D [

8,

23]. This conjoint risk [

24] suggests the need for directing health interventions at both parties. T2D [

25]. Some studies further indicate that digital technology may increase retention and acceptability of interventions among women with prior GDM, with the potential for long-term health behavior change [

26]. Still, a knowledge gap exists on how health promotion interventions influence motivation for health behaviors among women with prior GDM and their partners. This study aimed to investigate motivation for health behavior change among women with recent GDM and their partners after participating in the Face-it intervention.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design and setting

The current study followed a qualitative interview-based design.

In Denmark, screening for GDM is based on selected risk factors including pre-pregnancy BMI ≥27 kg/m

2, family history of diabetes, previous birth of a child with a birth weight ≥4500 g, glucosuria, polycystic ovary syndrome and multiple pregnancies [

28]. Pregnant women are diagnosed with GDM if a glucose level of ≥9 mmol/L is detected in a 2-hour 75 g oral glucose tolerance test [

29]. After diagnosis, the women are advised about diet, physical activity and self-monitoring of blood glucose, and if this treatment is not sufficient to prevent high blood glucose levels, insulin treatment is started [

30]. Due to the risk of fetal and birth complications, the women are monitored closely by a multidisciplinary team including midwives, obstetricians, nurses, dieticians and endocrinologists [

31]. After delivery, Danish guidelines recommend regular screening for T2D and counselling on diet and physical activity to reduce the women’s risk of future development of T2D [

30]. However, diabetes screening uptake is low among women with prior GDM [

32], and no other systematic follow-up or preventative initiatives exist.

2.2. The Face-it intervention

This study contributes to the process evaluation of the Danish Face-it intervention [

27]. The Face-it health promotion intervention aimed to reduce the risk of T2D and increase the quality of life in women with prior GDM and their families. The effectiveness of the intervention is being evaluated in a randomized controlled trial and details are published elsewhere [

27,

33]. Women with GDM and their partners were recruited from 2019-2022 through obstetric departments in the three largest cities in Denmark where the intervention was delivered. Women could participate in the trial regardless of their civil status. Thus, women without a partner and women with partners who declined to participate could participate alone. If both the woman and her partner accepted participation and the couple was randomized to the intervention group, the partner was invited to all intervention activities.

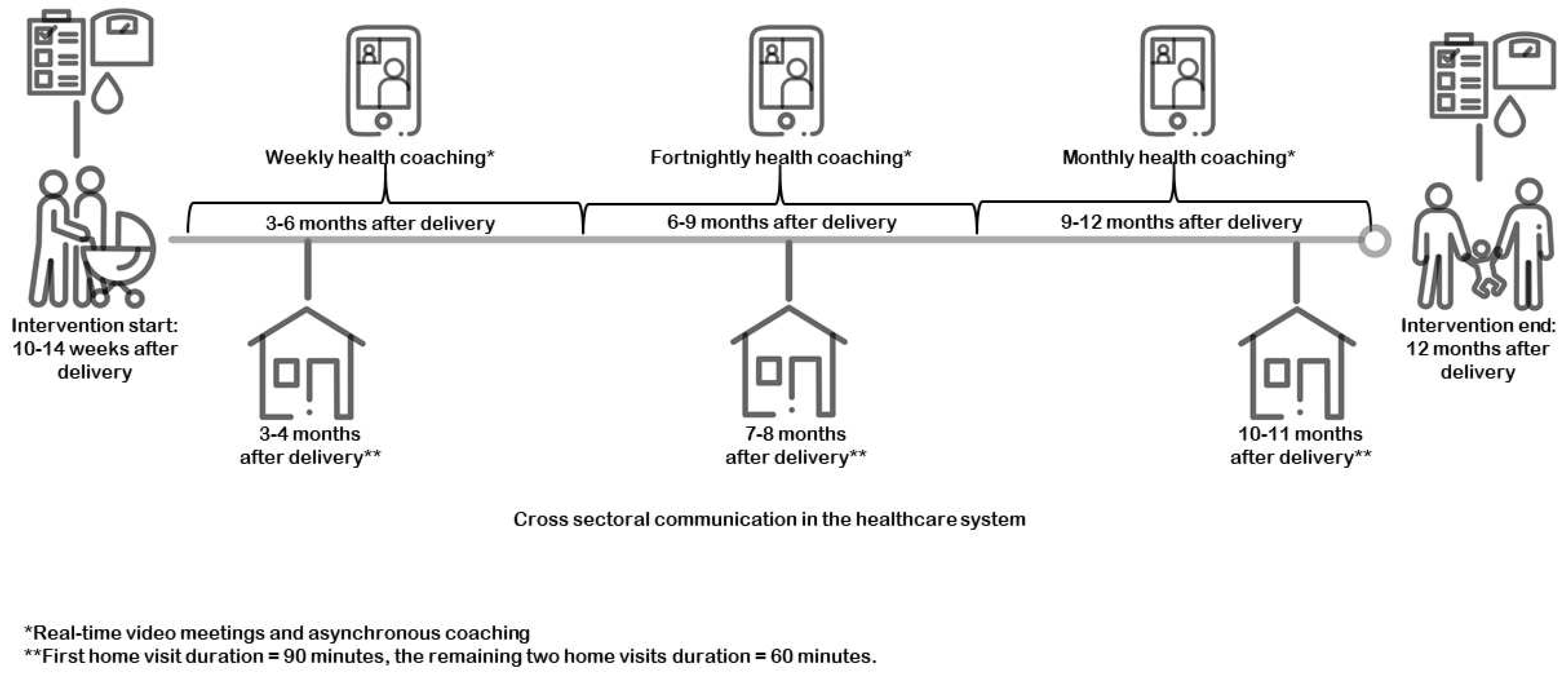

The Face-it intervention commenced 10-14 weeks after delivery and continued until the baby was around 12 months old. The intervention was based on three major components. The first component comprised three home visits supported by a dialogue tool ‘the family wheel’ which addressed five topics: GDM and risk/prevention of T2D; daily routines; food and meals; exercise/movement; and family, friends and network (

Figure S1). Municipality-based health visitors (nurses trained in new-born health and family wellbeing) delivered the home visits. The second component consisted of digital health coaching by trained health coaches (primarily health visitors) delivered through the digital platform ‘the LIVA app’. The LIVA app included features which enabled online interactions and individual- and family-based goal setting [

34]. The third intervention component involved the communication and coordination across health sectors to ensure that couples were provided with coherent information in the postpartum period. The three home visits were planned to be delivered at fixed time points, coordinated in collaboration between the couples and the health visitor. Digital health coaching was delivered with varying intensity across the nine months according to the needs and preferences of the family (see

Figure 1).

The healthcare professionals delivering the intervention received education about GDM and training on communicating about GDM, including the care pathway and the risk of T2D. Also, they were supported in embedding a health promoting perspective as defined by the WHO Europe, i.e., empowering, participatory, holistic, equitable and multi-strategy [

36]. For example, healthcare professionals were trained to focus on social support and well-being as pre-requisites for health behavior change and to be sensitive towards the family’s situational needs. This education was intended to enable the healthcare professionals to promote health in general, as well as promoting physical activity, healthy dietary behaviors, and breastfeeding through the mechanisms: Social support, self-efficacy, risk perception, health literacy and motivation. For this study, we narrow our scope and focus on motivation as an assumed mechanism of health behavior change.

2.3. Self-determination theory and interdependence theory

Theory-driven evaluation designs are recommended when investigating mechanisms of change in interventions to better understand intervention effects [

37]. To advance our understanding of how couples’ motivation for health behavior change was affected by the Face-it intervention, we applied self-determination theory (SDT) [

38] and interdependence theory [

39].

SDT is a theoretical perspective on human motivation that highlights humans’ inner resources for personality development and behavioral self-regulation [

38]. In this study, SDT was used in the analysis to understand women’s and their partners’ motivation for health behavior change. SDT distinguishes between extrinsic and intrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation is characterized by actions driven by a personal interest in practicing a behavior, e.g., joy, whereas extrinsic motivation is driven by external factors such as rewards, obligation, social acceptance and individual goals and values. SDT posits that the more internalized a motivation is to perform a behavior, the more likely the individual is to sustain this behavior. According to SDT,

relatedness, perceived competence, and

autonomy are underlying personal attributes that contribute to the internalization of individual motivation. Relatedness concerns the need to feel understood through the establishment of a non-judgmental, positive, and empathic environment. Perceived competence refers to one’s experienced ability to perform a behavior. SDT posits that motivation becomes more autonomously driven when individuals experience relatedness and perceived competence. Thus, autonomy involves the need to consider oneself the driver of one’s own behaviors [

38].

Interdependency theory developed by Lewis et al. is a dyadic theory, which can be used to understand each partner’s perspective, thereby revealing both individual and collective influences on health behaviors [

39]. Interdependence theory was applied in the analysis to investigate couples’ mutual motivation for health behavior change. The main hypothesis behind interdependence theory is that mutual support within the relationship is the most effective way to sustain health behaviors and that when health behaviors are perceived as meaningful to the couple and their relationship, the incentive for them to perform these behaviors increases. Lewis et al. incorporate pre-dispositional factors, which influence couples’ motivation for health behavior change.

Preferences for outcomes refers to extent to which the couples agree on project goals in terms of performing health behaviors within couples. Another pre-dispositional factor is couples’ interpretation of

health threat, which, in the case of GDM, is how couples’ perceive the risk and consequences of T2Das a cue to preventive action [

39]. Interdependence theory includes three other factors referring to

relationship functioning,

communication style and

gender, which were less evident in the data and thus absent in the results.

2.4. Data collection

We conducted semi-structured, couple interviews with women with recent GDM and their partners. All women and their partners, who had completed the Face-it intervention within the last year, between January 2020 and January 2021, were invited to participate through a written information letter sent via a secure digital platform (e-Boks). Non-respondent couples received a reminder text message approximately four weeks after the invitation. First author, AT, telephoned the couples, who agreed to participate, to schedule an interview. The majority of interviews were carried out in the homes of the participants. [

40]. However, due to restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic, four interviews were performed online. All interviews were conducted between mid-November 2021 to mid-February 2022.

Of the 27 couples invited, 14 couples agreed to participate in an interview. Nine couples did not respond, and four couples declined participation. Two couples indicated disinterest and two couples lacked time and energy to participate. The characteristics of the couples participating in interviews are presented in

Table 1.

AT, a female researcher, in her late 20s with a background in public health science conducted all interviews. Prior to this study, AT was involved in the development of the Face-it intervention and had, among other things, participated in the education of healthcare professionals delivering the intervention. Moreover, AT had also conducted interviews with the intervention deliverers in the early stages of implementation [

41]. Thus, AT was highly integrated in the intervention, which she actively leveraged in this study to develop and challenge her assumptions about the impact of the intervention on couples’ motivation for health behavior change. AT had no contact with the couples prior to inviting them to participate in the interviews for this present study.

An interview guide was developed by AT and discussed with KKN and HTM as well as with other researchers in the Face-it Study. An explorative approach focused on motivation was employed. The interview guide included questions about parenthood, perception of health, experiences with home visits and digital health coaching (See

Table S1). All interviews were audio recorded and/or online video recorded. The interviews lasted between 48 and 79 minutes.

Before the interviews were initiated, the couples were informed that the interviews would be used to provide knowledge to strengthen care for families in which the woman had GDM. During the interviews, an overview of the intervention activities (

Figure 1) and the family wheel (

Figure S1) were used as prompts to help women and partners recall their experiences with the intervention. The woman and partner were asked to write down their respective perceptions of the ‘useful’ and ‘less useful’ aspects of the intervention (Table 3). The woman or partner who said the least was asked to provide her/his reflections first to ensure their engagement in the interview. This exercise was not included in interviews performed online and when the presence of a child made it difficult for the couple to reflect separately on their answers.

2.5. Data analysis

Data analysis followed an abductive approach using reflexive thematic analysis in which the researcher’s position is continuously reflected upon to advance analysis [

42,

43]. Interviews were transcribed verbatim by AT or a research assistant. Initially, AT listened to all audio recordings to familiarize herself with the data and then coded all transcripts inductively. During the first reading of the empirical data, AT explored how couples reported on their perspectives on health behavior change during and after participating in the Face-it intervention. During this process, AT coded both assumed and unintended mechanisms of change, e.g., ‘mutual motivation for health behaviors’ or ‘lack of differentiation for individual motivation’. In the second coding of the empirical data, AT identified patterns related directly to motivation and thereafter looked for theories to complement and nuance the data. Thus, a second round of coding was guided by SDT and interdependence theory [

38,

44]. Themes and subthemes were created during this phase. Nvivo v12 was used to structure the coding process [

45]. Examples of the data analysis process are presented in

Table 2.

2.6. Ethical considerations

The Face-it trial is registered in ClinicalTrials (gov NCT03997773). The woman and partner gave written consent to participate through the Danish digital platform (e-Boks) after receiving information on study aim, pseudo-anonymity, and voluntary participation. Consent for audio and/or video recordings were obtained prior to the interviews. During couple interviews, staying sensitive to couple dynamics is important, and therefore, AT abstained from going into discussions which might negatively affect the couples’s relationship [

46]. The study is reported according to the Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) [

47].

3. Results

Guided by SDT and interdependence theory, we identified four themes related to couples’ motivation for health behavior change.

3.1. The need for relatedness after delivery

In the first theme, we find that couples’ feelings of relatedness – the need to feel connected with others – affected their motivation for health behavior change, consistent with SDT. The couples described their everyday life as characterized by limited ability to be spontaneous, time restrictions and an increased need for collaboration to ensure the baby’s wellbeing. Due to these requirements, many participants expressed that they would not have accepted participation if it had required them to leave their home. Also, most participants described it as critical that the hardship they faced caring for a baby was acknowledged in their interaction with the healthcare professionals.

‘We had some good talks about planning and what we wanted to do using the family wheel [dialogue tool used in the home visits], especially that sometimes you need to accept that the energy just isn’t there. And how you’re not supposed to rearrange your life at this time but rather use this period to regain energy.’

(Woman, Couple 11)

For instance, several couples stated that they experienced a need to relax to regain energy, e.g., by watching television after the baby was put to bed. When healthcare professionals recognized such needs as well as the emotional burden of being a parent, including the feeling of guilt of not living up to societal expectations of ‘proper’ parenthood, most couples reported feeling understood (also concurrent with relatedness) by the healthcare professional. In particular, advice given by healthcare professionals on family habits, e.g., meal planning, household chores and delegation of assignments between couple members, was mentioned by couples as enabling them to rethink their habits in a positive and non-judgmental way. Also, many couples stressed the importance of discussing coping strategies with the healthcare professional to relieve their stress, sleep deprivation and emotional burden:

‘I’m glad I took part in [the intervention] because obviously one has learned something. It’s not all about exercising and what one eats. It’s about feeling good at the same time. When [name of healthcare professional] suggested that I should insert a goal into the LIVA app reminding me to relax – that was just amazing instead of having a bad conscience about everything I didn’t do.’

(Woman, Couple 10)

3.2. Promoting competence and autonomy for health behavior change

The second theme deals with how feelings of competence and autonomy among the couples affected their motivation to engage in healthy dietary and physical activity behaviors. Most couples equated a healthy meal with a meal, which was homecooked, and physical activities concerned “putting on a sports bra or running shoes”. Lack of time was often described by couples as the main barrier to conduct such health behaviors. However, many couples described how the healthcare professionals in the Face-it intervention had broadened their views on the kind of behavior changes that could be considered health promoting. This new understanding of how even small changes might add up and positively affect health was accompanied by an expressed increased perceived competence, which in turn internalized their motivation to perform health behaviors, consistent with SDT.

She [healthcare professional] said “count everything when you talk about physical activity. It’s okay to go out in the garden and pick tomatoes or do garden work for 5 minutes. Walk to the grocery store. Take the stairs. If you spend 15 minutes pram walking, that’s fine”.

(Partner, Couple 4)

Furthermore, some couples described being encouraged by the healthcare professional to keep performing their preferred physical activities. As a result, couples experienced being more likely to practice that behavior because it resonated with their current interests, e.g., walking. Getting support from healthcare professionals to identify alternative solutions to unhealthy habits was also described as useful to couples. As an example of a behavioral change adopted after participating in the intervention, one couple mentioned buying cans of carbonated soft drinks instead of 1.5-liter bottles, and another couple stated:

Partner: We used to have a fast-food Friday with food from the grill or McDonalds. In a period where we had limited energy, we talked to her [healthcare professional] about finding fast-food alternatives.

Woman: Now, we can have a fast-food day with homemade pizza with salad and less cheese and more vegetables. So, healthier alternatives, but we still call it fast-food day.

(Couple 12)

Couples also reported situations during which their motivation to perform health behaviors became more externalized. Some couples considered the advice on health behaviors inappropriate, because their own health was not considered a priority while they had a small baby. Some couples described the advice from healthcare professionals as prescriptive in the sense that they felt that the healthcare professional told them what to do without considering their family’s current resources, needs and preferences. Consequently, these couples expressed feelings of low autonomy support from the healthcare professional, which, in line with SDT, externalized their motivation to improve diet and physical activity behaviors.

‘I think she [the healthcare professional] was a tough lady. She made some suggestions, but they weren’t always realistic. I don’t know if they have too many families [in the intervention] but she didn’t really consider who we are. I felt like she said, “just eat cabbage”, but with a small child and a husband who works a lot, it’s not that easy.’

(Woman, couple 7)

External motivation was also underscored when some women mentioned that they initially participated in the intervention mainly to support research, rather than to change health behaviors themselves.

3.3. Individual and mutual preferences for health behaviors

The third theme focuses on how concordant and discordant preferences among couples affected their individual and mutual motivation to perform health behaviors. Due to the demands of the child, couples viewed their family and its functionality as their main priority, which took precedence over individual health behaviors. In accordance with interdependence theory, common interests within the couple strengthened mutual motivation. Performing health-related activities with their children, as a family, was a shared priority among most couples. Experiencing support and advice from healthcare professionals on planning family-based activities, which focused on family well-being, increased their mutual motivation for engaging in such activities despite competing demands of everyday chores as portrayed by Couple 14:

Woman: We talked to the healthcare professional about wanting to go out more – like a walk in the woods. Not necessarily for the sake of being physically activity, but just as much for the fresh air and energy and the kids’ enjoyment.

Partner: It reminded us that even though we’re busy and we should also set up an office and clean up the kitchen and stuff like that. No! We’ll have to go outdoors for everyone’s sake.

As such, it seemed that couples’ mutual motivation increased when health behaviors were performed as a family, since this made them more fun. However, couples also expressed divergent individual preferences for engaging in health behaviors. Women were more likely than their partners to express their preference for spending time with their child over their interest in performing individual health behaviors. As one woman put it:

‘What if I had spent time at the gym, which I could have spent better with my children?’.

(Woman, Couple 10)

In addition to wanting to engage in family-based activities, partners also described an interest in individual activities or activities with their child(ren) without their spouse. Some couples, although mainly the partners, had successfully used digital health coaching through the LIVA app to increase their focus on weight loss, step counts etc. and found the possibility of individual support appealing.

‘When the opportunity presents itself, I take the pram with great pleasure and walk down to pick him [baby] up from the nursery instead of taking the car. Then it’s just us time. I hadn’t thought about that before [the intervention] in the same way. It’s healthy for me and for us that these healthcare professionals have rattled us in a well-intentioned way.’

(Partner, Couple 7)

Despite benefitting from the individual digital health coaching feature, couples noted that the LIVA app was unable to automatically synchronize with their android-based smartphones. This meant that couples had to manually register their health behaviors and goals into the app, which was perceived to be incompatible with the busy everyday life of the family. Motivated by external factors, e.g., registering in the app to please the health coach, decreased couples’ motivation to comply with the advice. For example, couples mentioned instances of performative reporting in the LIVA app which did not match their actual goals or health behaviors. At other times, couples mentioned that they felt that the feedback on the app was impersonal and auto-generated.

‘If I hadn’t registered for a week, then I had to sit and scroll back for each day, and I simply didn’t want to continue. I thought it was too much trouble.’

(Partner, Couple 5)

3.4. The health threat of future T2D as a cue to action

The fourth theme addressed how couples cognitively and emotionally respond to their risk of T2D diabetes and its perceived impact on their motivation for health behavior change. Most couples expressed being aware of the women’s future T2D risk. As suggested by interdependence theory, it was evident that couples’ motivation was affected very differently by how they interpreted the health threat. Many women indicated that the GDM diagnosis was linked to uncertainty because it was unclear to them how why they had developed GDM. The healthcare professionals often calmed the women and couples by trying to explain GDM as a diagnosis triggered by genes. These explanations seemed to calm the women and remove the guilt some women felt towards receiving the GDM diagnosis. The couples expressed how demystifying the GDM diagnosis increased their motivation to pursue health behaviors to reduce their T2D risk.

‘My first thought was, what could I have done differently? What did I do wrong? The fact that someone tells you that this [GDM] is just something the body does – and it’s [the risk] more pronounced among some women and some are placed in the GDM category.’

(Woman, Couple 2)

The majority of couples acknowledged the fact that changing their health behaviors might reduce their future T2D risk, which in turn increased their motivation for health behavior change. The fact that the child was also at increased risk of developing T2D was of high concern to the couples. This information acted as a cue to action for health behavior engagement due to the importance couples attributed to being a healthy family. Nonetheless, some couples perceived it as unrealistic to promote their health behaviors while having a small baby.

‘When the baby is out, you relax a bit. It’s hard. You don’t get the sleep you need and you’re tired and all those things and you’re overwhelmed by emotions, then it’s not carrots in the fridge you think about.’

(Woman, Couple 1)

Others described the development of GDM as a natural bodily response to pregnancy. In these situations, couples’ motivation for health behavior change seemed to be negatively affected by their belief that their risk of future T2D diabetes would be unaffected by changing their health behaviors.

Woman: Diabetes runs in the family. So, it wasn’t because of anything else that I developed gestational diabetes.

Partner: Yes, it was actually really random.

In general, the way in which the women interpreted their own risk affected their partners’ motivation to support them by engaging in health behaviors. For example, when knowledge of T2D risk had motivated the women to increase their focus on health behaviors, their partners tended to become supportive, which contributed to a mutual motivation for health behavior change.

You [woman] had figured out what it really was – what gestational diabetes meant and what you could do to prevent it – and you told me many times that it’s not just you it affects. It’s also [baby]. And then I thought “Okay, this is the way we need to go.”

(Partner, Couple 3)

Though most partners acknowledged the woman’s and child’s risk of T2D, none of the partners mentioned being at risk of diabetes themselves.

‘Of course, it’s mostly the woman’s body, which is affected. It’s not about my body.’

(Partner, Couple 2)

Rather, partners considered their participation in the intervention as highly relevant with regard to supporting health behaviors and thereby reducing the risk of diabetes in the woman and child.

4. Discussion

Our study investigated motivation as an assumed mechanism for health behavior change among couples after participating in the Face-it intervention. We found that a need for relatedness among couples seemed to facilitate competence and autonomy to engage in diet and physical activity behaviors. Also, differing preferences for such health behaviors existing within couples seemed to affect their motivation for health behavior change along with their perception of T2D as a health threat.

Feelings of relatedness were described by most couples as feeling connected to and understood by the healthcare professionals. Relatedness was established through creating a non-judgmental environment, by removing couples’ pressure of living up to the norms of perfect parenthood. Furthermore, healthcare professionals’ acknowledgment of the importance of psychosocial wellbeing and understanding of the couples’ daily stressors also seemed to strengthen couples’ feelings of relatedness. SDT posits that in interactions between patients and clinicians where medical advice is expected, relatedness is needed before giving advice because its presence renders receivers more likely to interpret the advice as informative rather than prescriptive [

38]. The diverse health-related topics on the family wheel may have enabled conversations about norms of health and parenthood, which resonated with couples’ need to feel recognized. Discussions about psychosocial wellbeing in particular seemed to generate relatedness among couples. This may be partly due to the prospect of failure, e.g., couples experiencing that they are not living up to ‘correct parenthood’ and the need for parents with a baby to feel competent to perform health behaviors [

48]. Gilbert et al. showed a similar tendency among women with GDM, namely that interventions which accounted for both psychosocial wellbeing (depression, anxiety, social support and sleep) and health behaviors were more often linked to successful adoption of healthy dietary and physical activity behaviors [

49]. Good mental health has also been identified as a vital facilitator for women with prior GDM to engage in physical activity [

50]. From couples’ accounts of participating in the Face-it intervention, it seems that the use of the family wheel and the intervention being home-based facilitated relatedness. Also, relatedness may have been enabled through face-to-face interactions as healthcare professionals can more easily tailor health advice to the needs of the couples. Thus, delivering home-based activities to women with prior GDM and their partners may increase motivation for health behavior change. Also, home-based delivery may have increased participation since most couples expressed that they would not have participated in the intervention if it had been delivered elsewhere.

Our findings suggest that ensuring couples’ experience of relatedness may be particularly relevant in the period after birth, to increase autonomous motivation for health behaviors. As such, advice needs to be tailored to the everyday lives of the couples to remove the pressure of trying to live up to societal parental and health recommendations. Counselling may appeal to couples’ internal motivation when it focuses on making small, realistic changes. Health visitors, being the primary profession to deliver the intervention, are used to working from a health-promoting perspective [

31]. Also, they are knowledgeable about the challenges of parenthood, and are highly trained in interaction [

31]. Therefore, they most likely also contributed to internalizing motivation for health behaviors among couples. For example, the health visitors may have contributed to identifying appropriate family-based health-related activities and enabled couples to adapt these activities to their own needs, which in turn contributed to couples’ perceived competence and autonomy. However, instances of inappropriate health behavior counselling were also reported by couples. As such, tailoring advice and counselling to the situational and personal needs of couples with a newborn and a history of GDM seems crucial to spur autonomous motivation. It is plausible that when couples transit into parenthood, they develop more internalized and mutual motivation for family-based activities, which include health-related behaviors such as those described in our study. Thus, based on the findings from this study, family-based health-related activities may spur mutual, autonomous motivation among couples with a history of GDM.

The LIVA app was intended to strengthen couples’ feelings of autonomy by enabling personalized goal setting at the individual- and family level. This was perceived as motivating by some couples. The healthcare professionals described how delivering digital health coaching via the Face-it intervention came with the risk of compromising their relationships with couples [

41]. Thus, it may be that face-to-face counselling may be necessary to increase couples’ motivation through relatedness. Technological barriers included the need for manual reporting of health behaviors due to a lack of synchronization of the app with android-based devices. Due to the need for manual registration and automated messages received in the LIVA app, couples’ mutual motivation for digital health coaching seemed to decrease due to its perceived incompatibility with family life. A recent review highlighted personalized goal setting and video coaching as highly acceptable features of digital health technology among women with prior GDM, making our findings only partly consistent with the available literature [

26]. In the Face-it intervention, more women than partners registered in the LIVA app, possibly indicating differing levels of interest in digital health coaching [

35]. Based on the current study, digital health coaching can facilitate motivation for health behaviors among some women with recent GDM and their partners, with personalized digital health coaching and less demanding technology further facilitating increased motivation among these couples. Ensuring a user-friendly registration practice in health technologies, like the LIVA app, seems to be essential for couples to engage with digital health coaching to promote health behaviors.

In our study, some couples seemed to acknowledge their future risk of developing T2D but perceived the time after delivery to be an unrealistic period for changing health behaviors. In contrast, other couples seemed motivated to engage in health behaviors due to the woman’s and child’s future risk of T2D. The current literature suggests that some women with prior GDM underestimate their risk of T2D development [

51],which may lead to decreased motivation for health behavior change [

52]. Similarly, to many couples in the current study, risk perception seemed to have a small or no effect on their motivation for health behavior change. Parson et al. further explored risk among women with prior GDM and concluded that fear of T2D onset can work as a motivational factor for engaging in health behavior change [

53]. The authors also proposed that diabetes risk may most optimally be addressed by considering both the woman’s personal beliefs and socio-cultural context [

53]. However, communicating about diabetes risk to couples was identified as troublesome by healthcare professionals in the development and delivery of the Face-it intervention [

33,

41]. Similar concerns have been documented among nurses, who have been found to under-communicate potential risk to avoid conflict with individuals they want to support [

54]. Still, it seemed that some couples in our study had a shared interest in changing health behaviors in order to become a healthy family. Thus, ensuring a non-judgmental environment, while providing information about the risk of diabetes (without it being normative or prescriptive), may be the most motivating way to create mutual, internalized motivation for health behaviors among couples. Still, more research is needed to understand how a motivational understanding of risk can be established in couples with a history of GDM.

We also identified how a woman’s perception of risk affected her partner’s interpretation of risk with both positive and negative implications for their motivation for health behavior change., Although evidence of the partner’s role remains limited in the literature, in the context of couples with a history of GDM, partners seem to be motivated to support family health behaviors [

25]. In our study, we found that partners did not consider themselves to be at risk, which according to interdependence theory may have decreased their motivation for health behavior change [

39]. A lack of motivation among partners may evoke an unsupportive home environment if partners persist in upholding unhealthy habits [

55]. Although T2D risk among partners is addressed in the intervention manual for delivery of the Face-it intervention, it may be that healthcare professionals could have emphasized this shared risk of T2D even further to increase mutual motivation for health behavior change. Altogether, couples’ perception of diabetes risk seemed to have differing effects on couples’ motivation for health behavior change.

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of this study is our focus on couples, which allowed us to explore both individual and mutual motivation for health behavior change [

40]. For example, we might not have identified the intrinsic motivation among couples for engaging in family-based activities if only the woman or the partner had been present. Our study also had limitations. Couples may have exaggerated their preference for family-based values. Further, the presence of the partner may have limited women’s wish to discuss the course of their pregnancies [

56]. Furthermore, couples sometimes found it difficult to recollect details about their experiences with the intervention, which may be a consequence of the interviews being performed up to 9 months after its completion. On the other hand, interviewing participants after they had completed the intervention, rather than during the intervention, allowed couples to reflect on the intervention as a whole. Directing questions at both women and their partners secured more equal involvement, facilitating more insights into partners’ views on the intervention.

We employed reflexive thematic analysis, which encourages researchers to continuously reflect upon and challenge their assumptions, to ensure transparent and trustworthy data collection and analysis [

42]. For example, in interviews with couples, AT sought to uphold an explorative approach to health by asking: ‘What is health to you and your family?’ To ensure transparency, data analysis was continuously discussed with the co-authors. SDT and interdependence theory helped to understand how motivation was established in couples. Combining two extensive theories increased sensitivity towards different interpersonal mechanisms, but may also have increased the chance of superficial application [

57].

5. Conclusions

Understanding motivation for health behavior change among couples with a history of GDM gives a unique insight into how health promotion efforts may be tailored to the everyday lives of this target group.

In general, couples perceived the Face-it intervention as useful, and our findings suggest that relatedness in the year after delivery was highly relevant to internalizing motivation for health behavior change among couples. Relatedness was established through couples’ feelings of connectedness to each other and understanding from the healthcare professionals. Specifically, couples experienced relatedness when they felt their situational resources (or lack thereof) were acknowledged as well as when couples’ psychosocial wellbeing e.g., emotional burdens of parenthood were prioritised. Home-based delivery and the health visitors’ relational and health promoting skills seemed to facilitate relatedness as well.

When couples became aware of their health-related everyday activities through interactions with the healthcare professional, they tended to report enhanced perceptions of autonomous motivation through increased perceived competence to perform health behaviors. In particular, it was perceived as useful when healthcare professionals supported couples to moderate the intensity of health activities to suit their hectic lives. Couples reported shared preferences for family-based activities which positively affected their mutual motivation according to the interdependence theory. Yet, partners appeared more likely than mothers to prefer doing things alone or with their baby.

Digital health coaching through the LIVA app seemed to accommodate couples’ differing interests for health behavior change. Manual registration was deemed inappropriate to family life and most likely makes couples’ (and other target groups’) motivation for engaging with digital health coaching more externally driven. Also, some couples registered only for the benefit of research and not for perceived benefit to themselves. Couples’ interpretation of their future risk of T2D varied greatly between and within couples and may be associated with challenges with risk communication on the part of healthcare professionals. Furthermore, the motivational impact of T2D as a health risk also ranged from having no to moderate impact on couples’ motivation for health behavior change. Addressing risk in a motivational way, i.e., by removing guilt of having had GDM and underscoring the potential benefits of adopting health behaviors in the family, may be key to ensuring mutual motivation for health behaviour change in a non-prescriptive way. Also, women’s interpretation of the risk of diabetes seemed to influence their partner’s risk perception in a way which either facilitated or inhibited their motivation to engage in health behaviors.

Across themes, individual tailoring to couples’ situational needs and beliefs seems vital to internalize their motivation for health behavior change. Thus, to secure engagement of the diverse group comprising women with prior GDM and their partners, we suggest targeting motivation through highly differentiated care. A dialogue tool like the family wheel, which address various health promoting topics, may facilitate increased motivation through increased relatedness. We propose training healthcare professionals in health promotion and risk communication and considering both individual- and family-based coaching opportunities. Knowledge gained from this study will contribute to the interpretation of the effects of the Face-it intervention and support the evidence base for health promotion among couples at increased T2D risk.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1. The interactive dialogue tool, the family wheel; Table S1. Key questions in the interview guide for couple interviews

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.T., K.K.N and H.T.M.; methodology, A.T., K.K.N and H.T.M.; software, A.T.; validation, A.T., K.K.N; H.T.M., H.M.A and D.M.J.; formal analysis, A.T., K.K.N and H.T.M.; investigation, A.T., K.K.N and H.T.M.; resources, A.T., K.K.N and H.T.M.; data curation, A.T., K.K.N and H.T.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.T., K.K.N; H.T.M., H.M.A. and D.M.J.; writing—review and editing, A.T., K.K.N; H.T.M., H.M.A. and D.M.J.; visualization, A.T.; supervision, H.T.M., K.K.N., D.M.J.; project administration, H.T.M.; funding acquisition, H.T.M, K.K.N, D.M.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper was embedded within AT’s PhD project which was funded by Aarhus University, Steno Diabetes Center Copenhagen, and the Face-it study. The Face-it study was funded by a grant from the Novo Nordisk Foundation NNF16OC0027826 and by in-kinds from the participation institutions (Principal Investigator, Helle Terkildsen Maindal).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee for Science and Health in the Capital Region of Denmark (H-18056033).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The qualitative data is unavailable due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the women and their partners who participated in interviews for this study. The authors also wish to thank the Face-it study group. Furthermore, we would like to thank the following institutions for their support: Steno Diabetes Center Aarhus, Steno Diabetes Center Copenhagen, Steno Diabetes Center Odense, Aarhus University, Rigshospitalet, Odense University Hospital, Aarhus University Hospital, Aarhus Municipality, Copenhagen Municipality, Odense Municipality and LIVA Healthcare. We are grateful to the families who participated in the Face-it study and to the healthcare professionals involved in recruitment, data collection and intervention delivery.

Conflicts of Interest

AT, KKN, and HTM are employed at Steno Diabetes Center Copenhagen, a public hospital and research institution under the Capital Region of Denmark, which is partly funded by a grant from Novo Nordisk Foundation. DMJ is employed at Steno Diabetes Center Odense, Odense University Hospital, a public hospital, and research institution under the Region of Southern Denmark, which is also partly funded by a grant from Novo Nordisk Foundation. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results. HMA is employed at Karolinska Institutet where she also receives funding. She reports no conflict of interest.

References

- Sun, H.; Saeedi, P.; Karuranga, S.; Pinkepank, M.; Ogurtsova, K.; Duncan, B.B.; Stein, C.; Basit, A.; Chan, J.C.; Mbanya, J.C. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, Regional and Country-Level Diabetes Prevalence Estimates for 2021 and Projections for 2045. Diabetes research and clinical practice 2021, 109119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, H.D.; Catalano, P.; Zhang, C.; Desoye, G.; Mathiesen, E.R.; Damm, P. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2019, 5, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Registry DMB Fødte og fødsler (1997- (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Song, C.; Lyu, Y.; Li, C.; Liu, P.; Li, J.; Ma, R.C.; Yang, X. Long-Term Risk of Diabetes in Women at Varying Durations after Gestational Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis with More than 2 Million Women. Obes Rev 2018, 19, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egan, A.M.; Enninga, E.A.L.; Alrahmani, L.; Weaver, A.L.; Sarras, M.P.; Ruano, R. Recurrent Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Narrative Review and Single-Center Experience. J Clin Med 2021, 10, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausen, T.D.; Mathiesen, E.R.; Hansen, T.; Pedersen, O.; Jensen, D.M.; Lauenborg, J.; Damm, P. High Prevalence of T2D and Pre-Diabetes in Adult Offspring of Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus or Type 1 Diabetes: The Role of Intrauterine Hyperglycemia. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennison, R.A.; Chen, E.S.; Green, M.E.; Legard, C.; Kotecha, D.; Farmer, G.; Sharp, S.J.; Ward, R.J.; Usher-Smith, J.A.; Griffin, S.J. The Absolute and Relative Risk of T2D after Gestational Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 129 Studies. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 2021, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, K.; Ross, N.; Meltzer, S.; Costa, D.D.; Nakhla, M.; Habel, Y.; Rahme, E. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in Mothers as a Diabetes Predictor in Fathers: A Retrospective Cohort Analysis. Diabetes Care 2015, 38, e130–e131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C. Maternal Outcomes and Follow-up after Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabet Med 2014, 31, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goveia, P.; Cañon-Montañez, W.; Santos, D. de P.; Lopes, G.W.; Ma, R.C.W.; Duncan, B.B.; Ziegelman, P.K.; Schmidt, M.I. Lifestyle Intervention for the Prevention of Diabetes in Women With Previous Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018, 9, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Yang, Y.; Cui, D.; Li, C.; Ma, R.C.W.; Li, J.; Yang, X. Effects of Lifestyle Intervention on Long-Term Risk of Diabetes in Women with Prior Gestational Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Obes Rev 2021, 22, e13122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroda, V.R.; Christophi, C.A.; Edelstein, S.L.; Zhang, P.; Herman, W.H.; Barrett-Connor, E.; Delahanty, L.M.; Montez, M.G.; Ackermann, R.T.; Zhuo, X.; et al. The Effect of Lifestyle Intervention and Metformin on Preventing or Delaying Diabetes Among Women With and Without Gestational Diabetes: The Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study 10-Year Follow-Up. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2015, 100, 1646–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Chen, M.; Makama, M.; O’Reilly, S. Preventing T2D in Women with Previous Gestational Diabetes: Reviewing the Implementation Gaps for Health Behavior Change Programs. Semin Reprod Med 2020, 38, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntoumanis, N.; Ng, J.Y.Y.; Prestwich, A.; Quested, E.; Hancox, J.E.; Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C.; Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M.; Lonsdale, C.; Williams, G.C. A Meta-Analysis of Self-Determination Theory-Informed Intervention Studies in the Health Domain: Effects on Motivation, Health Behavior, Physical, and Psychological Health. Health Psychology Review 2021, 15, 214–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwasnicka, D.; Dombrowski, S.U.; White, M.; Sniehotta, F. Theoretical Explanations for Maintenance of Behaviour Change: A Systematic Review of Behaviour Theories. Health Psychol Rev 2016, 10, 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, G.F.; Audrey, S.; Barker, M.; Bond, L.; Bonell, C.; Hardeman, W.; Moore, L.; O’Cathain, A.; Tinati, T.; Wight, D.; et al. Process Evaluation of Complex Interventions: Medical Research Council Guidance. BMJ 2015, 350, h1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennison, R.A.; Fox, R.A.; Ward, R.J.; Griffin, S.J.; Usher-Smith, J.A. Women’s Views on Screening for T2D after Gestational Diabetes: A Systematic Review, Qualitative Synthesis and Recommendations for Increasing Uptake. Diabet Med 2020, 37, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ørtenblad, L.; Høtoft, D.; Krogh, R.H.; Lynggaard, V.; Juel Christiansen, J.; Vinther Nielsen, C.; Hedeager Momsen, A.-M. Women’s Perspectives on Motivational Factors for Lifestyle Changes after Gestational Diabetes and Implications for Diabetes Prevention Interventions. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab 2021, 4, e00248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, R.; Miller, D.; Mottola, M.; Giroux, I.; Donovan, L. Translating Healthy Living Messages to Postpartum Women and Their Partners After Gestational Diabetes (GDM): Body Habitus, A1C, Lifestyle Habits, and Program Engagement Results From the Families Defeating Diabetes (FDD) Randomized Trial. American Journal of Health Promotion 2017, 089011711773821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazeau, A.-S.; Meltzer, S.J.; Pace, R.; Garfield, N.; Godbout, A.; Meissner, L.; Rahme, E.; Da Costa, D.; Dasgupta, K. Health Behaviour Changes in Partners of Women with Recent Gestational Diabetes: A Phase IIa Trial. BMC public health 2018, 18, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyler, D.; Stimpson, J.P.; Peek, M.K. Health Concordance within Couples: A Systematic Review. Social Science & Medicine 2007, 64, 2297–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.E. The Health Capital of Families: An Investigation of the Inter-Spousal Correlation in Health Status. Soc Sci Med 2002, 55, 1157–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabootari, M.; Hasheminia, M.; Guity, K.; Ramezankhani, A.; Azizi, F.; Hadaegh, F. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in Mothers and Long Term Cardiovascular Disease in Both Parents: Results of over a Decade Follow-up of the Iranian Population. Atherosclerosis 2019, 288, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pace, R.; Brazeau, A.-S.; Meltzer, S.; Rahme, E.; Dasgupta, K. Conjoint Associations of Gestational Diabetes and Hypertension With Diabetes, Hypertension, and Cardiovascular Disease in Parents: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol 2017, 186, 1115–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almli, I.; Haugdahl, H.S.; Sandsæter, H.L.; Rich-Edwards, J.W.; Horn, J. Implementing a Healthy Postpartum Lifestyle after Gestational Diabetes or Preeclampsia: A Qualitative Study of the Partner’s Role. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2020, 20, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Tan, A.; Madden, S.; Hill, B. Health Professionals’ and Postpartum Women’s Perspectives on Digital Health Interventions for Lifestyle Management in the Postpartum Period: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, K.K.; Dahl-Petersen, I.K.; Jensen, D.M.; Ovesen, P.; Damm, P.; Jensen, N.H.; Thøgersen, M.; Timm, A.; Hillersdal, L.; Kampmann, U.; et al. Protocol for a Randomised Controlled Trial of a Co-Produced, Complex, Health Promotion Intervention for Women with Prior Gestational Diabetes and Their Families: The Face-It Study. Trials 2020, 21, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damm, P.; Ovesen, P.; Svare, J.; Andersen, L.; Jensen, D.M.; Lauenborg, J. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM). Screening and Diagnosis. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Diagnostic Criteria and Classification of Hyperglycaemia First Detected in Pregnancy; World Health

Organization, 2013.

- Damm, P.; Ovesen, P.; Andersen, L.; Møller, M.; Fischer, L.; Mathiesen, E. Clinical Guidelines for Gestational

Diabetes Mellitus (GDM). Screening, Diagnosis Criteria, Treatment and Control and Follow-up after Birth; The

Danish Health Authority, board of Diabetes Management, 2010. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- The Danish Health Auhority Recommendations for maternity care [Anbefalinger for svangreomsorgen]; 2021.

- Nielsen, J.H.; Olesen, C.R.; Kristiansen, T.M.; Bak, C.K.; Overgaard, C. Reasons for Women’s Non-Participation in Follow-up Screening after Gestational Diabetes. Women and Birth 2015, 28, e157–e163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maindal, H.T.; Timm, A.; Dahl-Petersen, I.K.; Davidsen, E.; Hillersdal, L.; Jensen, N.H.; Thøgersen, M.; Jensen, D.M.; Ovesen, P.; Damm, P.; et al. Systematically Developing a Family-Based Health Promotion Intervention for Women with Prior Gestational Diabetes Based on Evidence, Theory and Co-Production: The Face-It Study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandt, C.J.; Christensen, J.R.; Lauridsen, J.T.; Nielsen, J.B.; Søndergaard, J.; Sortsø, C. Evaluation of the Clinical and Economic Effects of a Primary Care Anchored, Collaborative, Electronic Health Lifestyle Coaching Program in Denmark: Protocol for a Two-Year Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res Protoc 2020, 9, e19172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, N.H.; Kragelund Nielsen, K.; Dahl-Petersen, I.K.; Timm, A.; O’Reilly, S.; Maindal, H.T. ; On behalf of the core investigator group. Fidelity of the Face-It Health Promotion Intervention for Women with Recent Gestational Diabetes and Their Partners. (Unpublished).

- Rootman, I.; Goodstadt, M.; Hyndman, B.; McQueen, D.V.; Potvin, L.; Springett, J.; Ziglio, E. Evaluation in Health Promotion: Principles and Perspectives; World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe, 2001; ISBN 978-92-890-1359-8.

- McIntyre, S.A.; Francis, J.J.; Gould, N.J.; Lorencatto, F. The Use of Theory in Process Evaluations Conducted alongside Randomized Trials of Implementation Interventions: A Systematic Review. Transl Behav Med 2018, 10, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. American psychologist 2000, 55, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M.A.; McBride, C.M.; Pollak, K.I.; Puleo, E.; Butterfield, R.M.; Emmons, K.M. Understanding Health Behavior Change among Couples: An Interdependence and Communal Coping Approach. Soc Sci Med 2006, 62, 1369–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åstedt-Kurki, P.; Paavilainen, E.; Lehti, K. Methodological Issues in Interviewing Families in Family Nursing Research. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2001, 35, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timm, A.; Nielsen, K.K.; Jensen, D.M.; Maindal, H.T. Acceptability and Adoption of the Face-It Health Promotion Intervention Targeting Women with Prior Gestational Diabetes and Their Partners: A Qualitative Study of the Perspectives of Healthcare Professionals. Diabet Med 2023, e15110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermans, S.; Tavory, I. Theory Construction in Qualitative Research: From Grounded Theory to Abductive Analysis. Sociological Theory 2012, 30, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leask, C.F.; Sandlund, M.; Skelton, D.A.; Altenburg, T.M.; Cardon, G.; Chinapaw, M.J.M.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Verloigne, M.; Chastin, S.F.M.; on behalf of the GrandStand, S.S. and T.G. on the M.R.G. Framework, Principles and Recommendations for Utilising Participatory Methodologies in the Co-Creation and Evaluation of Public Health Interventions. Research Involvement and Engagement 2019, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo 2020.

- Bjørnholt, M.; Farstad, G.R. ‘Am I Rambling?’ On the Advantages of Interviewing Couples Together. Qualitative Research 2014, 14, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): A 32-Item Checklist for Interviews and Focus Groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timm, A.; Kragelund Nielsen, K.; Joenck, L.; Husted Jensen, N.; Jensen, D.M.; Norgaard, O.; Terkildsen Maindal, H. Strategies to Promote Health Behaviors in Parents with Small Children—A Systematic Review and Realist Synthesis of Behavioral Interventions. Obesity Reviews 2022, 23, e13359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, L.; Gross, J.; Lanzi, S.; Quansah, D.Y.; Puder, J.; Horsch, A. How Diet, Physical Activity and Psychosocial Well-Being Interact in Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: An Integrative Review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buelo, A.K.; Kirk, A.; Lindsay, R.S.; Jepson, R.G. Exploring the Effectiveness of Physical Activity Interventions in Women with Previous Gestational Diabetes: A Systematic Review of Quantitative and Qualitative Studies. Preventive Medicine Reports 2019, 14, 100877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, A.; Turk, N.; Duru, O.K.; Mangione, C.M.; Panchal, H.; Amaya, S.; Castellon-Lopez, Y.; Norris, K.; Moin, T. Association of T2D Risk Perception With Interest in Diabetes Prevention Strategies Among Women With a History of Gestational Diabetes. Diabetes Spectrum 2022, 35, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.; McEwen, L.N.; Piette, J.D.; Goewey, J.; Ferrara, A.; Walker, E.A. Risk Perception for Diabetes Among Women With Histories of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care 2007, 30, 2281–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsons, J.; Sparrow, K.; Ismail, K.; Hunt, K.; Rogers, H.; Forbes, A. A Qualitative Study Exploring Women’s Health Behaviours after a Pregnancy with Gestational Diabetes to Inform the Development of a Diabetes Prevention Strategy. Diabetic Medicine 2019, 36, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olin Lauritzen, S.; Sachs, L. Normality, Risk and the Future: Implicit Communication of Threat in Health Surveillance. Sociology of Health & Illness 2001, 23, 497–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reczek, C. The Promotion of Unhealthy Habits in Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Intimate Partnerships. Social Science & Medicine 2012, 75, 1114–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarhin, D. Conducting Joint Interviews With Couples: Ethical and Methodological Challenges. Qual Health Res 2018, 28, 844–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birken, S.A.; Powell, B.J.; Shea, C.M.; Haines, E.R.; Alexis Kirk, M.; Leeman, J.; Rohweder, C.; Damschroder, L.; Presseau, J. Criteria for Selecting Implementation Science Theories and Frameworks: Results from an International Survey. Implementation Science 2017, 12, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).