Submitted:

26 May 2023

Posted:

29 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

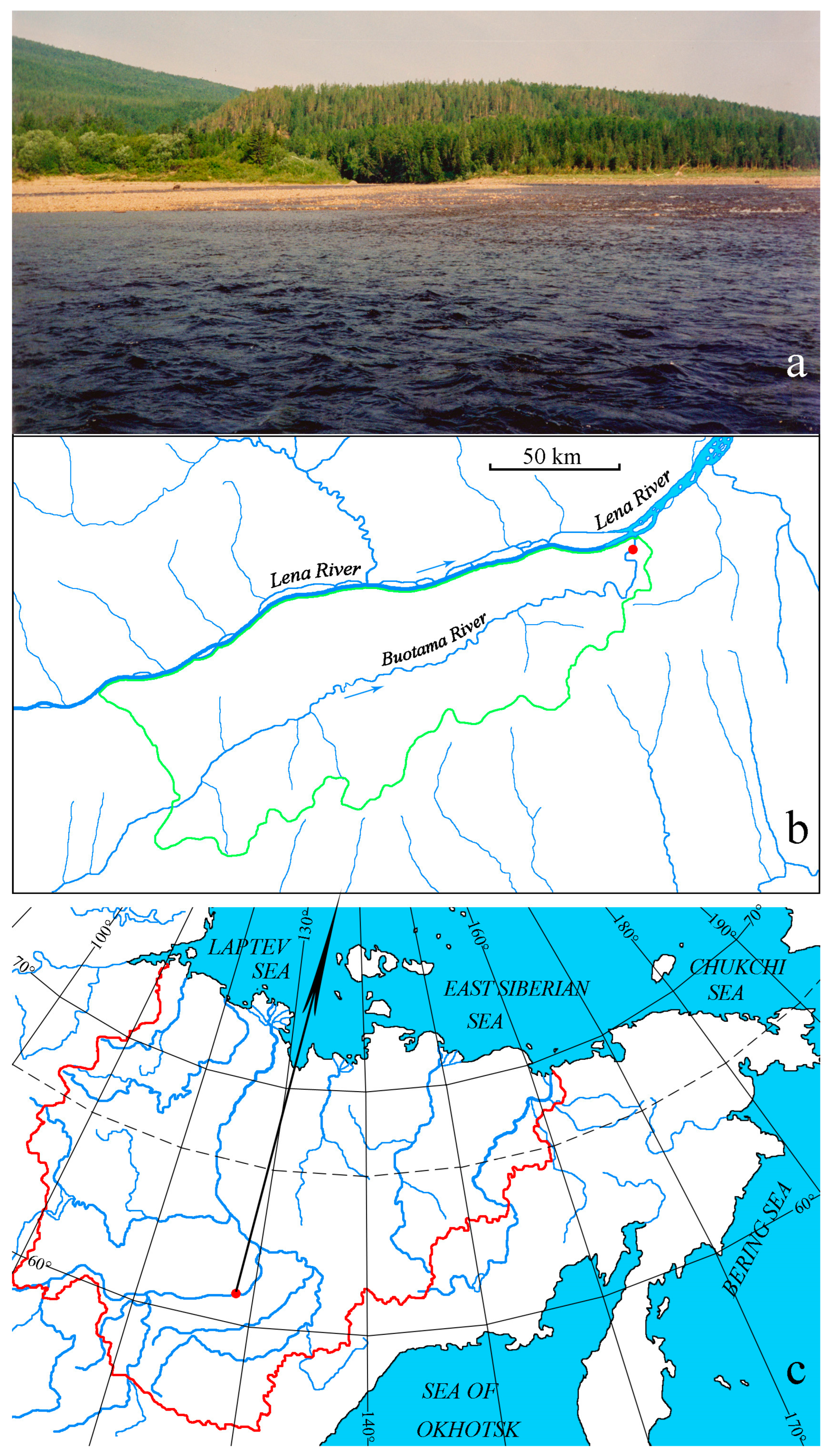

2.1. Study area

2.2. Sampling

2.3. Algological analysis

2.4. Water chemistry analysis

2.5. Detection of cyanotoxins by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry

2.6. PCR analysis of cyanotoxin biosynthesis genes

2.7. DNA extraction, purification and PCR

2.8. Molecular Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Water chemistry

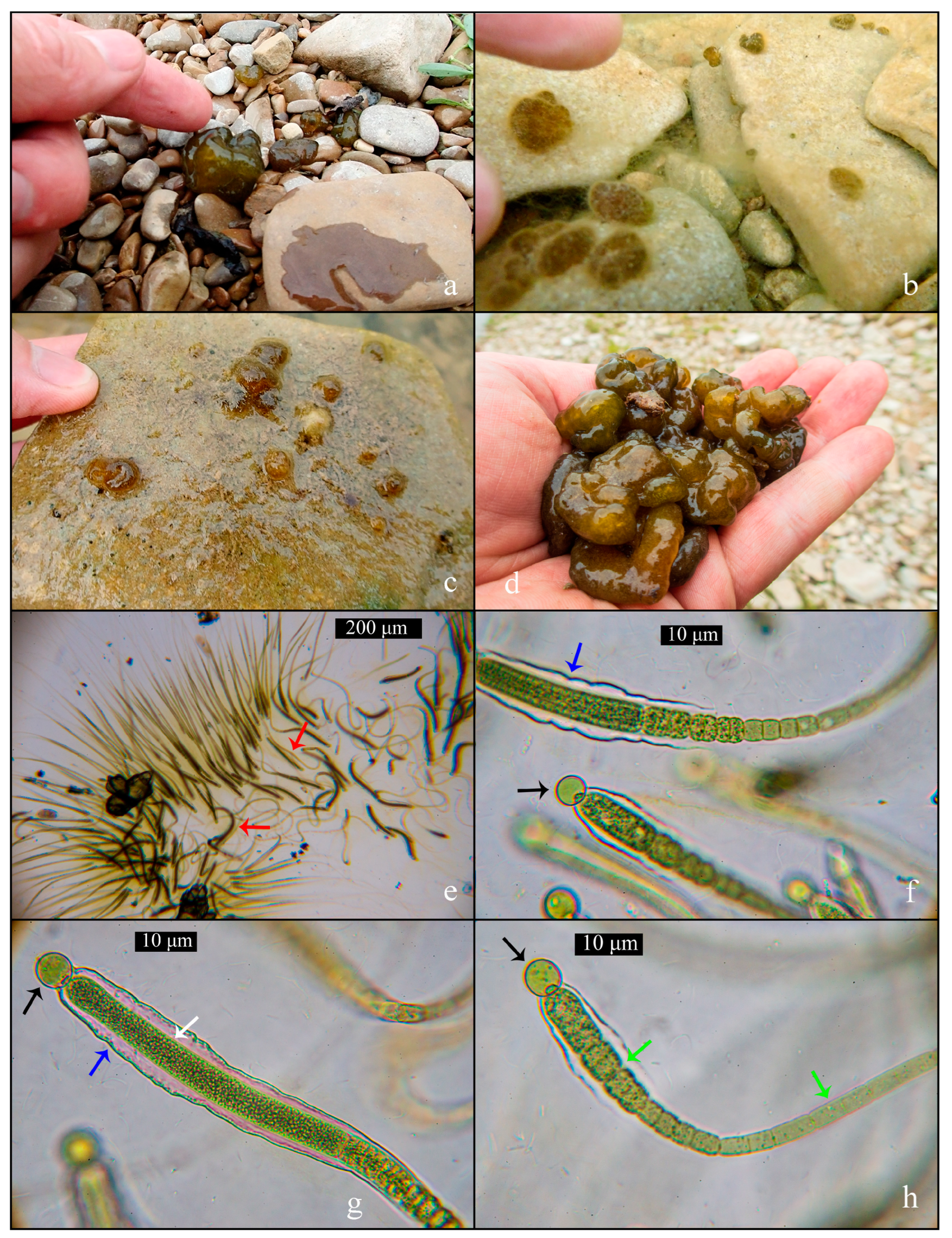

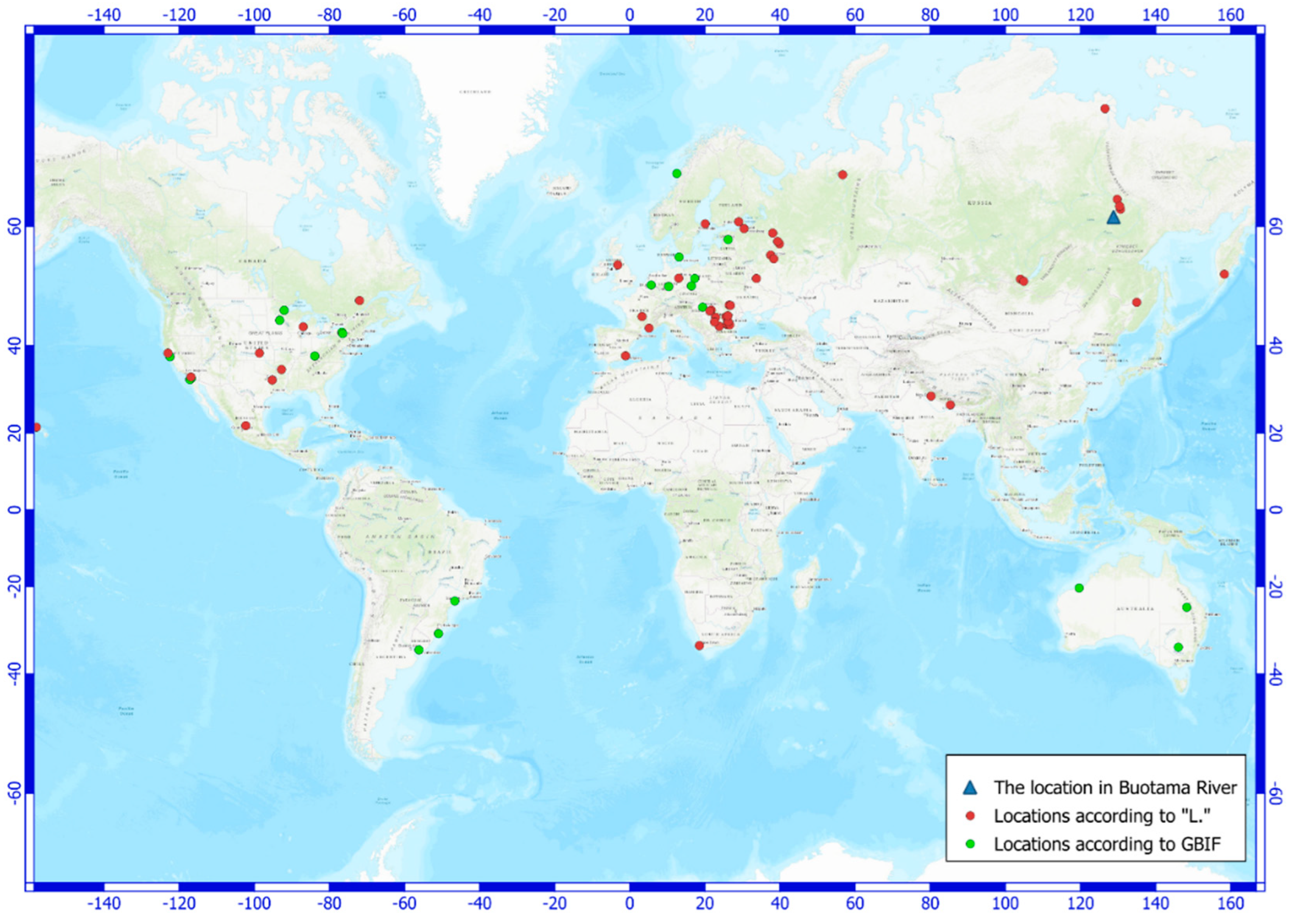

3.2. Field algological observations

3.3. Microscopic survey

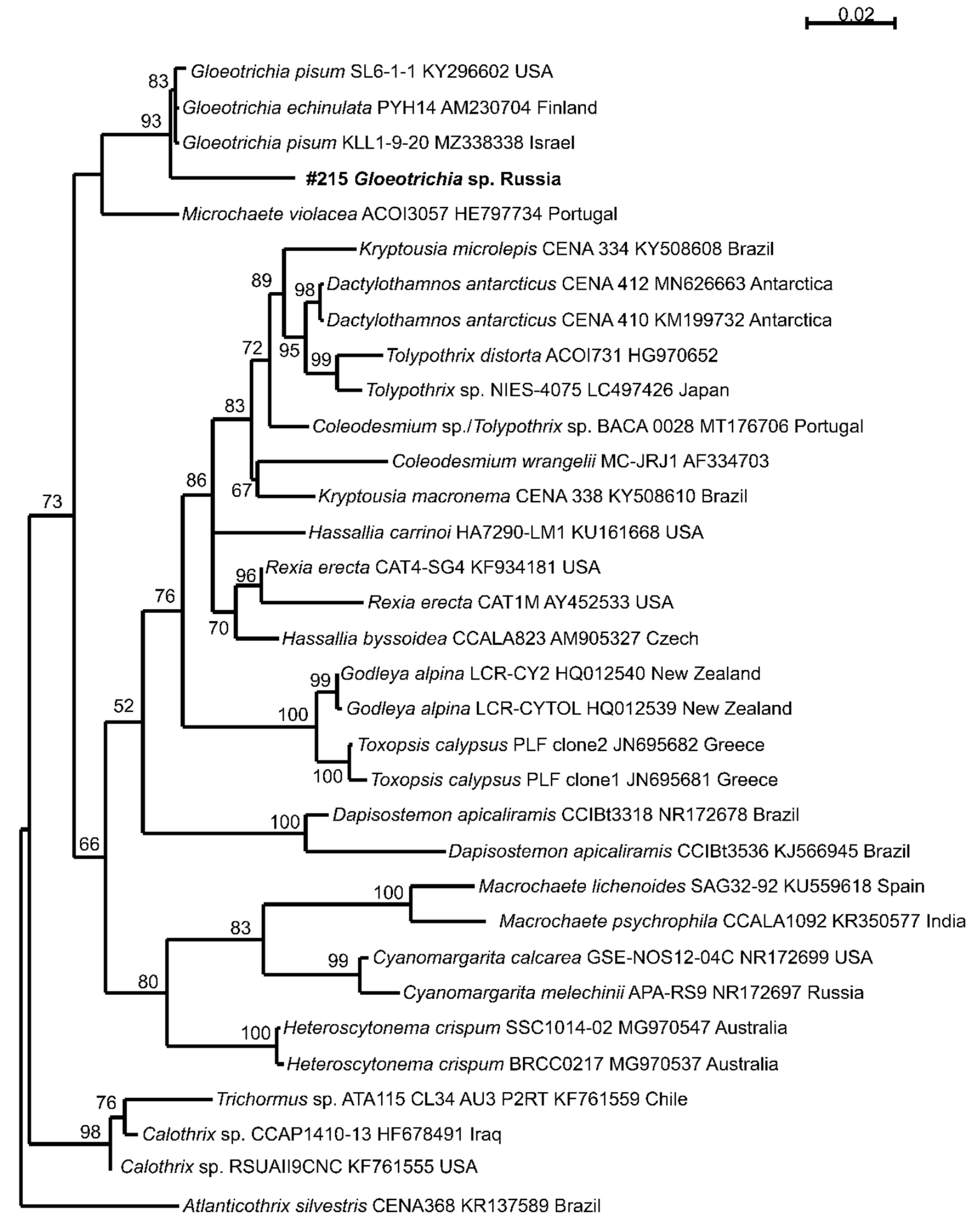

3.4. Phylogeny

3.5. Cyanotoxins detection

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Codd, G.A.; Morrison, L.F.; Metcalf, J.S. Cyanobacterial toxins: risk management for health protection. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 2005, 203, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paerl, H.W.; Huisman, J. Climate change: A catalyst for global expansion of harmful cyanobacterial blooms. Environmental Microbiology 2009, 1, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neil, J.M.O.; Davis, T.W.; Burford, M.A.; Gobler, C.J. The rise of harmful cyanobacteria blooms: The potential roles of eutrophication and climate change. Harmful Algae 2012, 313–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaget, V.; Hobson, P.; Keulen, A.; Newton, K.; Monis, P.; Humpage, A.; Weyrich, L.; Brookes, J. Toolbox for the sampling and monitoring of benthic cyanobacteria. Water Research 2020, 169, 115222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.; Kelly, L.; Bouma-Gregson, K.; Humbert, J.; Laughinghouse, H.; Lazorchak, J.; McAllister, T.; McQueen, A.; Pokrzywinski, K.; Puddick, J.; Quiblier, C.; Reitz, L.; Ryan, K.; Vadeboncoeur, Y.; Zastepa, A.; Davis, T. Toxic benthic freshwater cyanobacterial proliferations: Challenges and solutions for enhancing knowledge and improving monitoring and mitigation. Freshwater Biology 2020, 65, 1824–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heino, J.; Virkkala, R.; Toivonen, H. Climate change and freshwater biodiversity: detected patterns, future trends and adaptations in northern regions. Biological Reviews 2009, 84, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winder, M.; Sommer, U. Phytoplankton response to a changing climate. Hydrobiologia 2012, 698, 5–16. [CrossRef]

- Korneva, L.G. Invasions of alien species of planktonic microalgae into the fresh waters of Holarctic (Review). Russian Journal of Biological Invasions 2014, 5, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang-Yona, N.; Alster, A.; Cummings, D.; Freiman, Z.; Kaplan-Levy, R.; Lupu, A.; Malinsky-Rushansky, N.; Ninio, S.; Sukenik, A.; Viner-Mozzini, Y.; Zohary, T. Gloeotrichia pisum in Lake Kinneret: A successful epiphytic cyanobacterium. J. Phycol. 2023, 59, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, C.C.; Haney, J.F.; Cottingham, K.L. First report of microcystin-LR in the cyanobacterium Gloeotrichia echinulata 2007, 22, 337–339. [CrossRef]

- Carey, C.C.; Ewing, H.A.; Cottingham, K.L. Occurrence and toxicity of the cyanobacterium Gloeotrichia echinulata in low-nutrient lakes in the northeastern United States. Aquatic Ecology 2012, 46, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamann, S. "Toxin Production and Population Dynamics of Gloeotrichia echinulata with Considerations of Global Climate Change". Masters Theses 2015, 775. http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/theses/775.

- Cantoral Uriza, E.A.; Asencio, A.D.; Aboal, M. Are We Underestimating Benthic Cyanotoxins? Extensive Sampling Results from Spain. Toxins 2017, 9, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiry, M.D.; Guiry, G.M. AlgaeBase. World-wide electronic publication, National University of Ireland, Galway. Available online: https://www.algaebase.org (accessed on 29 March 2023).

- Strunecky, O.; Ivanova, A. An updated classification of cyanobacterial orders and families based on phylogenomic and polyphasic analysis. Journal of Phycology 2023, 59, 12–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izyumenko, S.A. Climate of the Yakut ASSR (atlas). Ed. Leningrad: Hydrometeorological Publishing House, Russia, 1968; 32 p. (In Russian).

- State Water Register. Available online: http://textual.ru/gvr/index.php?card=243859 (accessed on 23 March 2023). (In Russian).

- Surface water resources of the USSR. Lensko-Indigirsky district. Leningrad: Gidrometeoizdat, USSR, 1972; 651 p. (In Russian).

- Chistyakov G. Ye. Water resources of the rivers of Yakutia; Moscow: Nauka, Russia, 1964; 255 p. (In Russian).

- Komárek, J. Heterocytous Genera. Cyanoprokaryota; Springer Spektrum, Berlin, 2013; 3 (3), 3–1130.

- Semenov, A.D. (Ed.) Guidance on the chemical analysis of surface waters of the land; Gidrometeoizdat: Leningrad, USSR, 1977; 541 p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Chernova, E. Chernova, E., Russkikh, Ia., Voyakina, E., Zhakovskaya, Z. Occurrence of microcystins and anatoxin-a in eutrophic lakes of Saint Petersburg, Northwestern Russia. Oceanol. Hydrobiological Stud. 2016, 45 (4), 466–484. [CrossRef]

- Jungblut, A.D.; Neilan, B.A. Molecular identification and evolution of the cyclic peptide hepatotoxins, microcystin and nodularin, synthetase genes in three orders of cyanobacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 2006, 185, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihali, T.K.; Kellmann, R.; Muenchhoff, J.; et al. Characterization of the gene cluster responsible for cylindrospermopsin biosynthesis, Applied and Environmental. Microbiology 2008, 74, 716–722. [Google Scholar]

- Ballot, А.; Fastner, J.; Wiedner, C. Paralytic shellfish poisoning toxin-producing cyanobacterium Aphanizomenon gracile in Northeast Germany. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 1173–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantala‒Ylinen, A.; Känä, S.; Wang, H.; Rouhiainen, L.; Wahlsten, M.; Rizzi, E.; Berg, K.; Gugger, M.; Sivonen, K. Anatoxin–a synthetase gene cluster of the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain 37 and molecular methods to detect potential producers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 7271–7278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmotte, A.; Van Der Auwera, C.; De Wachter, R. Structure of the 16S ribosomal RNA of the thermophilic cyanobacteria Chlorogloeopsis HTF (‘Mastigocladus laminosus HTF’) strain PCC7518 and phylogenetic analysis. FEBS Lett. 1993, 317, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neilan, B.A.; Jacobs, D.; Therese, D.D.; Blackall, L.L.; Hawkins, P.R.; Cox, P.T.; Goodman, A.E. rRNA Sequences and Evolutionary Relationships among Toxic and Nontoxic Cyanobacteria of the Genus Microcystis. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1997, 47, 693–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nübel, U.; Garcia-Pichel, F.; Muyzer, G. PCR primers to amplify 16S rRNA genes from cyanobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63, 3327–3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, T.A. BioEdit: A User-Friendly Biological Sequence Alignment Editor and Analysis Program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symposium Series 1999, 41, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, D.; Cavanaugh, M.; Clark, K.; Karsch-Mizrachi, I.; Lipman, D.; Ostell, J. Sayers EW. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefler, F.; Berthold, D. Dail Laughinghouse H 4th. CyanoSeq: a database of cyanobacterial 16S rRNA sequences with curated taxonomy. J Phycol. [CrossRef]

- Kozlov, A.M.; Darriba, D.; Flouri, T.; Morel, B.; Stamatakis, A. RAxML-NG: A fast, scalable, and user-friendly tool for maximum likelihood phylogenetic inference. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 4453–4455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, T.M.; Creevey, C.J.; Pentony, M.M.; Naughton, T.J.; Mclnerney, J.O. Assessment of methods for amino acid matrix selection and their use on empirical data shows that ad hoc assumptions for choice of matrix are not justified. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2006, 6(1), 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaut, A. FigTree Version 1.4.4. 2020. (Default Version). Available online: http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Gabyshev, V.A. Gabyshev V.A., Gabysheva O.I. Phytoplankton of the largest rivers of Yakutia and adjacent territories of Eastern Siberia; Novosibirsk: SibAk, Russia, 2018; 414 p. (In Russian).

- Getzen, M.V. Algae of Pechora river basin. Leningrad: Nauka, USSR, 1973; 148 pp. (In Russian).

- Kiselev, G.A.; Balashova, N.B.; Ulanova, A.A. Ecological characteristics of algae from the lakes of Samoilovsky Island (Lena Delta Nature Reserve, Russia). In Proceedings of the IV International conference «Advances in modern phycology», Kyiv, Ukraine, 23–25 May 2012. (In Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Melekhin, A.V.; Davydov, D.A.; Borovichev, E.A.; Shalygin, S.S.; Konstantinova, N.A. CRIS – service for input, storage and analysis of the biodiversity data of the cryptogams. Folia Cryptogamica Estonica 2019, 56, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBIF.org. GBIF Occurrence (07 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Komarenko, L.Ye.; Vasilyeva, I.I. Freshwater diatoms and blue-green algae of water bodies of Yakutia. Moscow: Nauka, Russia, 1975. 424 p. (In Russian).

- Kopyrina, L.; Pshennikova, P.; Barinova, S. Diversity and ecological characteristic of algae and cyanobacteria of thermokarst lakes in Yakutia (northeastern Russia). International Journal of Oceanography and Hydrobiology 2020, 49, 99–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharova, V. I.; Kuznetsova, L. V.; Ivanova, Ye. I. et al. Diversity of the flora of Yakutia; Novosibirsk: Publishing house of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Russia, 2005; 328 p. (In Russian).

- CYANOpro. Available online: http://kpabg.ru/cyanopro/?q=node/96073 (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Elenkin, A.A. Kamchatka expedition of Fyodor Pavlovich Ryabushinsky. Botanical department. Issue. 2. Spore plants of Kamchatka: 1) Algae, 2) Mushrooms. Printing house P.P. Ryabushinsky: Moscow, Russia, 1914, 1–402. (In Russian).

- Medvedeva, L.A., Nikulina, T.V. Catalogue of freshwater algae of the southern part of the Russian Far East; Vladivostok: Dalnauka, Russia, 2014; 271 p. (In Russian).

- Gabyshev, V. A.; Tsarenko, P. M.; Ivanova A., P. Diversity and features of the spatial structure of algal communities of water bodies and watercourses in the Lena River estuary. Inland water biology 2019, 12(1), S1–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, W. K. Trophic state, eutrophication and nutrient criteria in streams. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2007, 22, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadeboncoeur, Y.; Moore, M.; Stewart, S.; Chandra, S.; Atkins, K.; Baron, J.; Bouma-Gregson, K.; Brothers, S.; Francoeur, S.; Genzoli, L.; Higgins, S.; Hilt, S.; Katona, L.; Kelly, D.; Oleksy, I.; Ozersky, T.; Power, M.; Roberts, D.; Smits, A.; Timoshkin, O.; Tromboni, F.; Zanden, M.; Volkova, E.; Waters, S.; Wood, S.; Yamamuro, M. Blue Waters, Green Bottoms: Benthic Filamentous Algal Blooms Are an Emerging Threat to Clear Lakes Worldwide. Bioscience 2021, 71, 1011–1027, PMID:34616235; PMCID: PMC8490932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeNicola, D. M. Periphyton responses to temperature at different ecological levels. In Algal ecology: Freshwater benthic ecosystem; San Diego, USA: Academic press, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Vuglinsky, V.; Valatin, D. Changes in Ice Cover Duration and Maximum Ice Thickness for Rivers and Lakes in the Asian Part of Russia. Natural Resources 2018, 9, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollerbakh, M.M.; Kosinskaya, Ye.K.; Polyanskiy, V.I. Blue green algae. Identification guide to freshwater algae of the USSR. Moscow: Nauka, USSR, 1953; 650 p. (In Russian).

- Starmach, K. Cyanophyta – Sinice. Glaucophyta – Glaukofity. Flora Słodkowodna Polski; Warszawa: PWN, Poland, 1966; 2, 808 p. (in Polish).

- Jüttner, F.; Watson, S. Biochemical and Ecological Control of Geosmin and 2-methylisoborneol in Source Waters. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2007, 73(14), 4395–4706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitzfeld, B. C.; Lampert, C. S.; Spaeth, N.; Mountfort, D.; Kaspar, H.; Dietrich, D. Toxin production in cyanobacterial mats from ponds on the McMurdo ice shelf, Antarctica. Toxicon 2000, 38, 1731–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungblut, A. D.; Hoeger, S. J.; Mountfort, D.; Hitzfeld, B.; Dietrich, D.; Neilan, B. Characterization of microcystin production in an Antarctic cyanobacterial mat community. Toxicon 2006, 47, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.; Mountfort, D.; Selwood, A.; Holland, P.; Puddick, J.; Cary, S. Widespread distribution and identification of eight novel microcystins in Antarctic cyanobacterial mats. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 7243–7251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinteich, J.; Wood, S.; Küpper, F.; Camacho, A.; Quesada, A.; Frickey, T.; Dietrich, D. Temperature-related changes in polar cyanobacterial mat diversity and toxin production. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2012, 2, 356–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinteich, J.; Hildebrand, F.; Wood, S.; Cirés, S.; Agha, R.; Quesada, A.; Pearce, D.; Convey, P.; Küpper, F.; Dietrich, D. Diversity of toxin and non-toxin containing cyanobacterial mats of meltwater ponds on the Antarctic Peninsula: A pyrosequencing approach. Antarct. Sci. 2014, 26, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrapusta, E.; Wegrzyn, M.; Zabaglo, K.; Kaminski, A.; Adamski, M.; Wietrzyk, P.; Bialczyk, J. Microcystins and anatoxin-a in Arctic biocrust cyanobacterial communities. Toxicon 2015, 101, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabyshev, V. A.; Sidelev, S. I.; Chernova, E. N.; Gabysheva, O. I.; Voronov, I. V.; Zhakovskaya Z., A. Limnological characterization and first data on the occurrence of toxigenic cyanobacteria and cyanotoxins in the plankton of some lakes in the permafrost zone (Yakutia, Russia). Contemporary Problems of Ecology 2023, 16, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Mean value | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|

| pH | 8.47 | 0.0354 |

| TDS, mg L-1 | 185.76 | 1.8385 |

| Hardness, mmol. L-1 | 2.40 | 0.0141 |

| Ca, mg L-1 | 45.69 | 0.2687 |

| Mg, mg L-1 | 1.46 | 0.0566 |

| Na, mg L-1 | 1.19 | 0.0707 |

| K, mg L-1 | 0.58 | 0.0283 |

| HCO3, mg L-1 | 109.84 | 0.7071 |

| Cl, mg L-1 | 14.18 | 0.4243 |

| SO4, mg L-1 | 12.82 | 0.2828 |

| N-NH4, mg L-1 | 0.13 | 0.0071 |

| N-NO3, mg L-1 | 0.03 | 0.0071 |

| N-NO2, mg L-1 | 0.03 | 0.0 |

| Si-SiO2, mg L-1 | 2.04 | 0.2828 |

| P tot, mg L-1 | < 0.04 | 0.0028 |

| PО4, mg L-1 | < 0.02 | 0.0028 |

| Color, Pt/Co grad. | 44 | 4.2426 |

| COD, mg O L-1 | 20.20 | 2.1213 |

| Fe tot, mg L-1 | < 0.05 | 0.0028 |

| Petrochemicals, mg L−1 | 0.005 | 0.0014 |

| Phenols, mg L−1 | 0.0005 | 0.0001 |

| Mn, µg L-1 | 33.00 | 5.6569 |

| Cu, µg L-1 | 6.00 | 0.7071 |

| Ni, µg L-1 | 4.40 | 0.7071 |

| Zn, µg L-1 | 13.70 | 1.1314 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).