1. Introduction

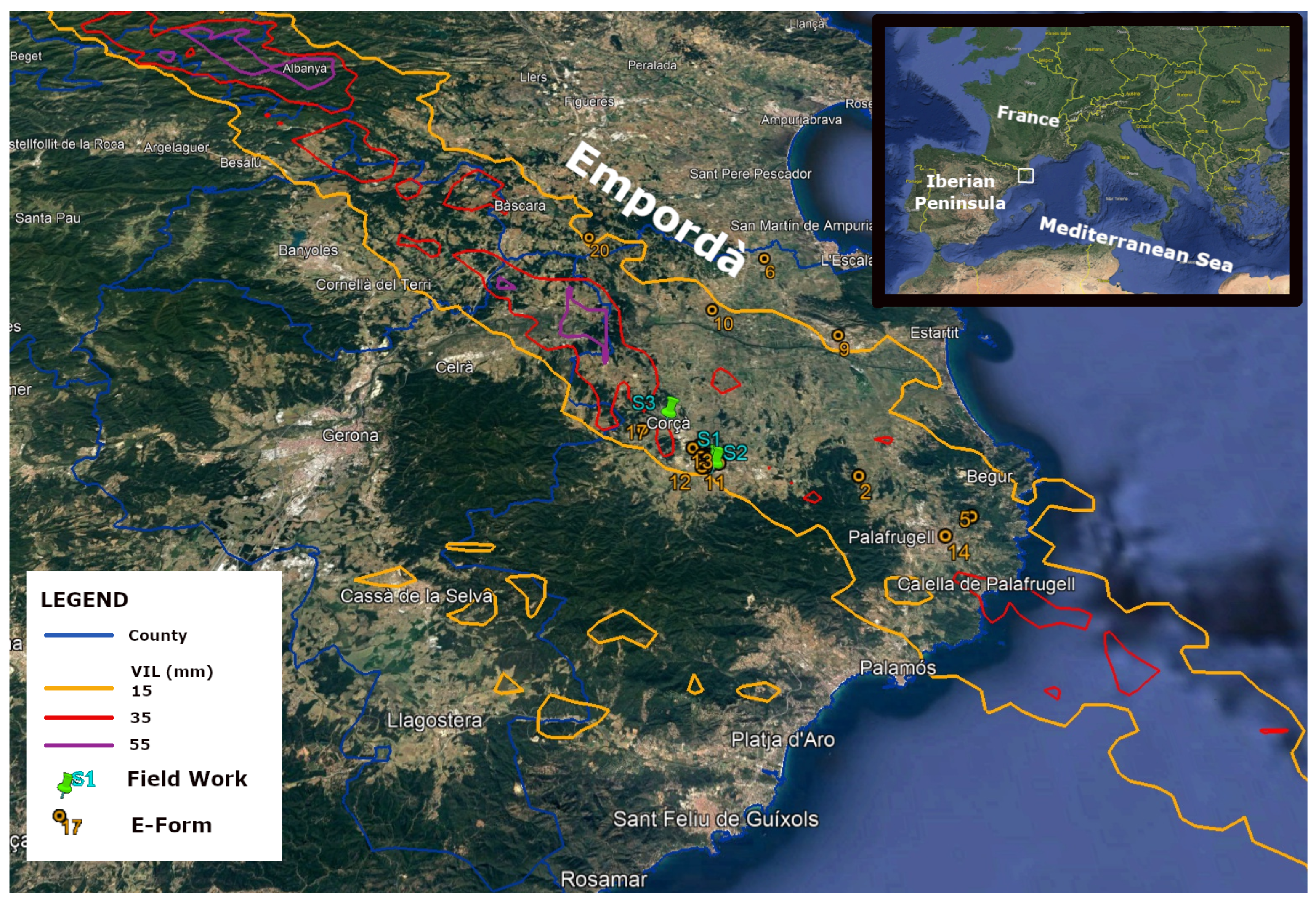

The afternoon of 30 August 2022 will remain in the memory of the inhabitants of La Bisbal de l’Empordà (green pins labelled as "S1" and "S2" in

Figure 1) and the surrounding villages for decades. The small town was hit by the most destructive hailstorm occurred in the Iberian Peninsula in the last few years. Large hailstones of 10 cm in diameter fell in a city of 11,000 inhabitants and produced much damage to the population (1 little girl died, and more than 60 people were injured) and to the infrastructure (most cars and roofs suffered impacts with economic losses over the 5,6 M€ [

1]). The event has repercussions in the meteorological community around the World (see, for instance, the report of the European Severe Storm Laboratory [

2]).

The cases of hailstorms in Catalonia are frequent and have led to different analyses of the associated atmospheric patterns [

3], campaigns for developing tools for diagnosing hail in thunderstorms [

4], or the implementation of nets for protecting crops in certain regions [

5]. Besides, [

6] or [

7] studied the thermodynamics associated with the different types of precipitation: from liquid to large hail. However, the affected area and the hail size are the first questions of interest: the area is by far to be the most usual, and on the other hand, the size is much larger than the historical records, from analyses such [

8] or [

9].

The combination of the radar fields with ground registers ([

10] or [

11]) has allowed confirming the high spatial variability of the hail falls in the region of study, in a similar way to other countries around the World [

12], [

13], [

14] or [

15]. In this way, field works becomes a crucial tool for understanding the hail-fall nature and goes deeper into the diagnosis improvement and forecasting tools [

16]. One operational use of the weather radar in Catalonia in recent years has been the delimitation of the area of affectation by hail falls through the VIL product (see

Figure 1 and [

17]).

Regarding the hail size, the largest register in Catalonia was 7 cm until the event of analysis according to the bibliography [

11]. However, giant hail (this is, stones with diameter over 10 cm [

18]) is not uncommon in the United States [

19] or [

20], Argentina [

21], and, more recently, in the Mediterranean [

22] or [

23]. The objective is to present the comparison results between radar fields and a survey made some months later than the event occurrence. The research has been made by combining the direct analysis with the information provided by different sources, through the electronic survey, and from the visual reports and other data given by some spotters. The final goal is to contextualize the event regarding the spatial variability and the extra-ordinariness in front of other cases in Catalonia, the Mediterranean Basin, or around the World.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Area of Study

Figure 1 shows the area of study, which is the North-Eastern part of Catalonia (located in the NE of the Iberian Peninsula). The region is known as the Empordà, marked with a white rectangle in the top-right panel of the figure, and the total extent considered is 12,416 km

(including a part of the sea and some neighbourhood counties). The hailstorm of 30 August 2022 hit a large part of the area inside the solid orange line region.

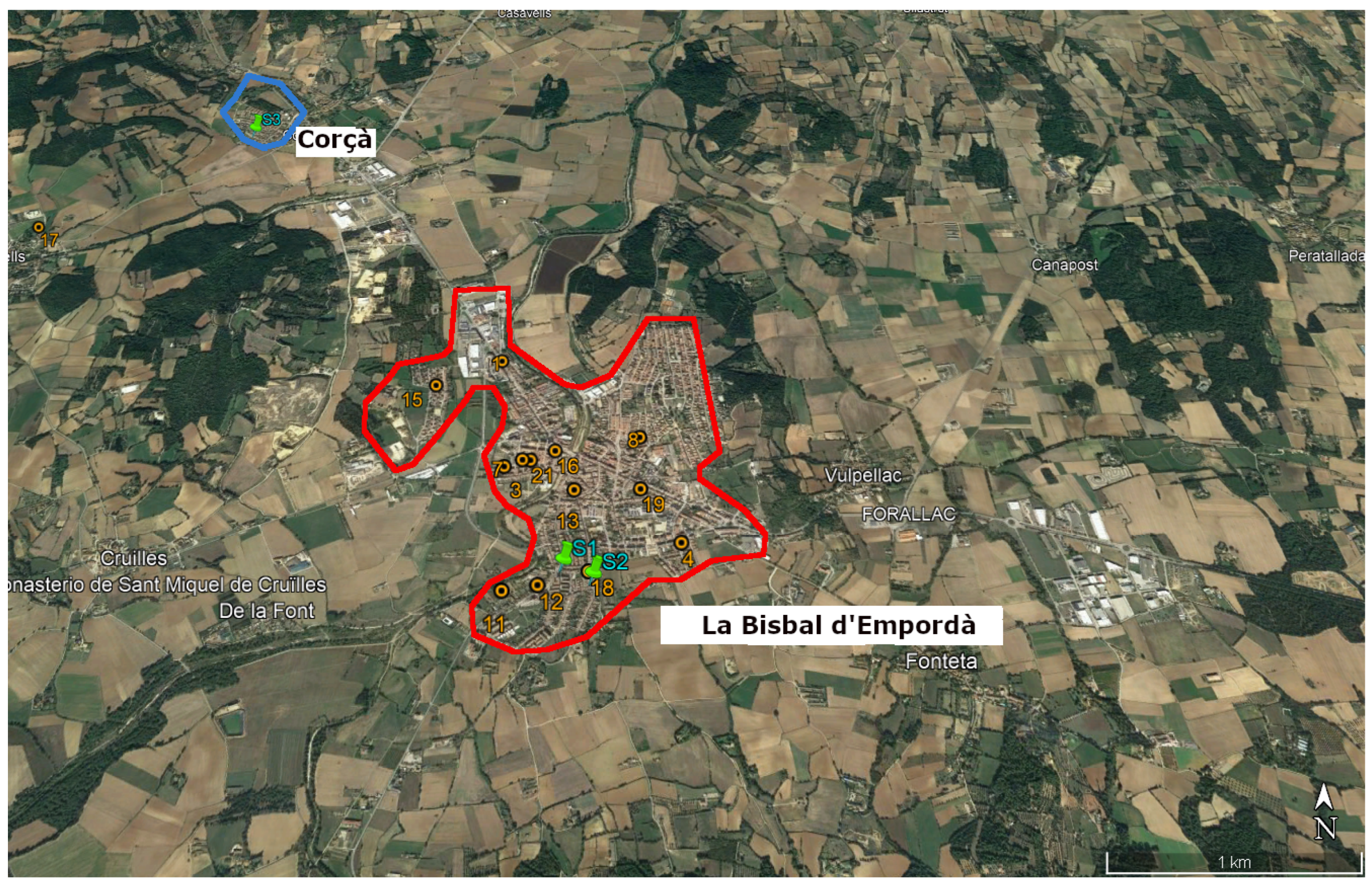

The event epicentre was La Bisbal d’Empordà and its surroundings. It is the capital of the Southern Empordà county and has a population of 11,000 inhabitants.

Figure 2 shows the limits of the village (in red) and of Corçà, a tiny town at the NW of the first location (the limits marked in blue). This region has an area of 20 km

.

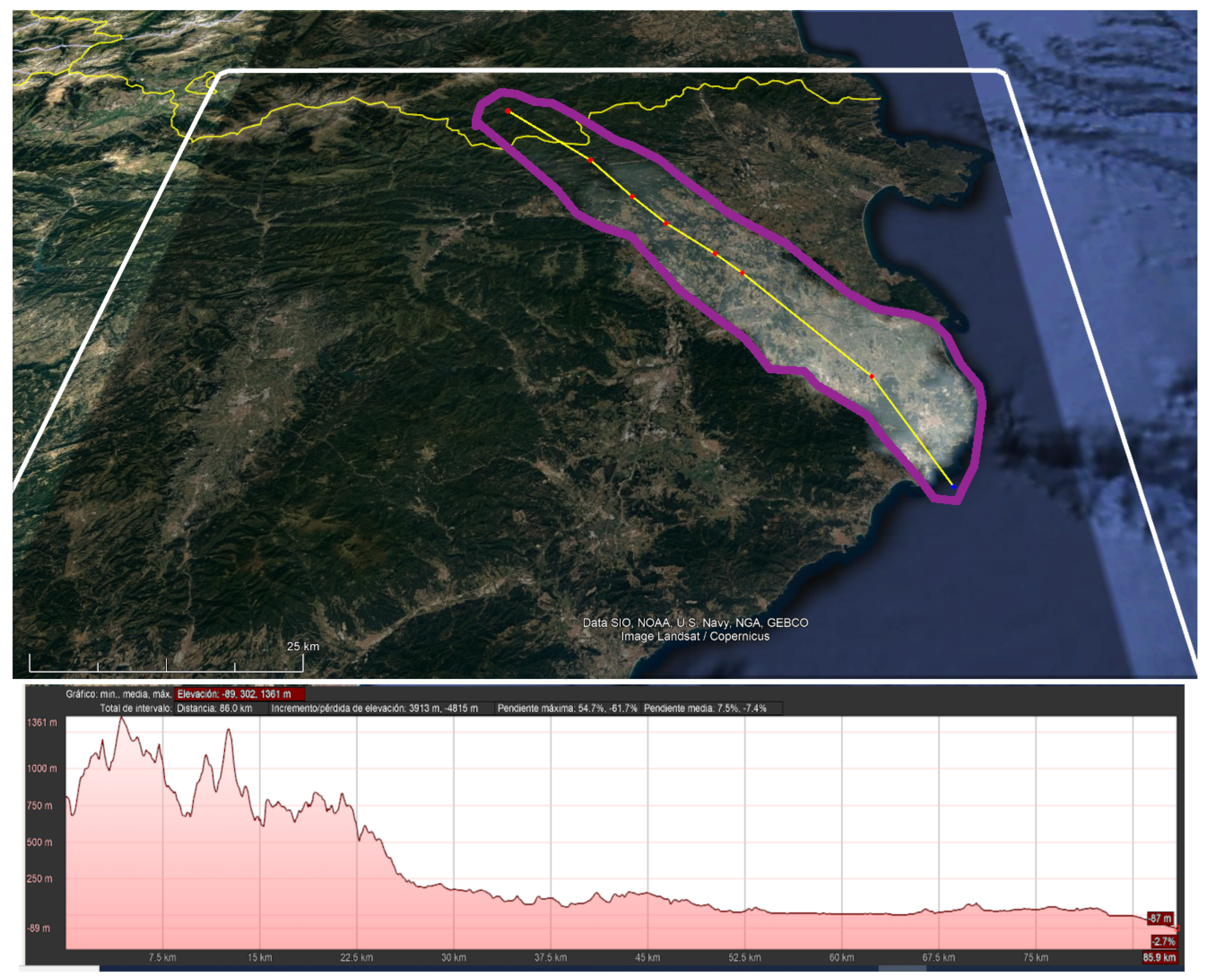

Figure 3 shows the hail swath generated using radar data, delimited by the purple line. The yellow line marks the transect considered for generating the vertical prole of the elevation (topography), presented in the below panel of the same figure. It is possible to distinguish two differentiated terrains. In the first 25 km of the trajectory, including the birth of the thunderstorm, heights between 1,360 and 250 m in steep terrain. From 25 to 85 km (where the thunderstorm reached the coastal line), the terrain was mostly plane, with elevations between 250 and 0 m, with progressive and soft downward slopes.

2.2. Data Used

2.2.1. Radar Data

We have used the maximum daily VIL product of the composite of the Radar Network (hereafter, XRAD) of the Servei Meteorològic de Catalunya for delimiting the region of interest. The XRAD consists of four C-Band single-pol radars covering the whole territory of Catalonia at different vertical levels (depending on the distance to the radars and the beam blockage of each part of the region). Each radar generates a full volume with a time resolution of 6 minutes, the same resolution as all the different products, including the composite VIL. The operative spatial resolution is 1 km X 1 km and uses the maximum value of the four radars at each field pixel. However, we have used an experimental spatial resolution of 150 m X 150 m. The maximum daily field is generated at the end of the day using the 240 composite maps. The area of affectation estimation is similar to that in [

17]. In that previous study, the selected optimal VIL threshold was 20 mm, according to the ground reports of affectation in crops.

2.2.2. Form Results

After different conversations with some spotters of the regions, the technicians of the Servei Meteorològic de Catalunya impulse an online survey spread through social networks. The proposed questions were:

- (1)

What are the coordinates of your location?

- (2)

At what time do you think it was the event at your location?

- (3)

What was the duration of the event?

- (4)

Which was the maximum size of the stones?

- (5)

Were all the stones regular in size?

It is worth noting that we delivered the form three months after the event. This delay had two purposes: first, to reduce the exaggeration of the observations, cited in the bibliography [

15], [

24], [

25] or [

26]. Of course, it is impossible to remove the bias caused by the density population in this research because we searched for registers at the time of the event, not those observations some hours after, when people moved to farms or small villages to observe the damages in those places. The second purpose was to minimize the effect on the observers caused by the damage claims to insurance and the administrations.

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Event: A Comparison between Radar Data and the Electronic Form

The electronic form contains 28 valid answers that provide valuable information about the event. Twenty of the reports corresponded to La Bisbal de l’Empordà, allowing a very detailed composition of the event for the city (reports cover practically all the districts). We compared this information to the VIL composite product (for 6-minute periods and the maximum daily field). The rest of the reports, more dispersed, also help to validate the radar product performance in areas far from the epicentre but also with some damages. This section describes the event from the point of view of the testimonies, according to their comments to the different suggested questions.

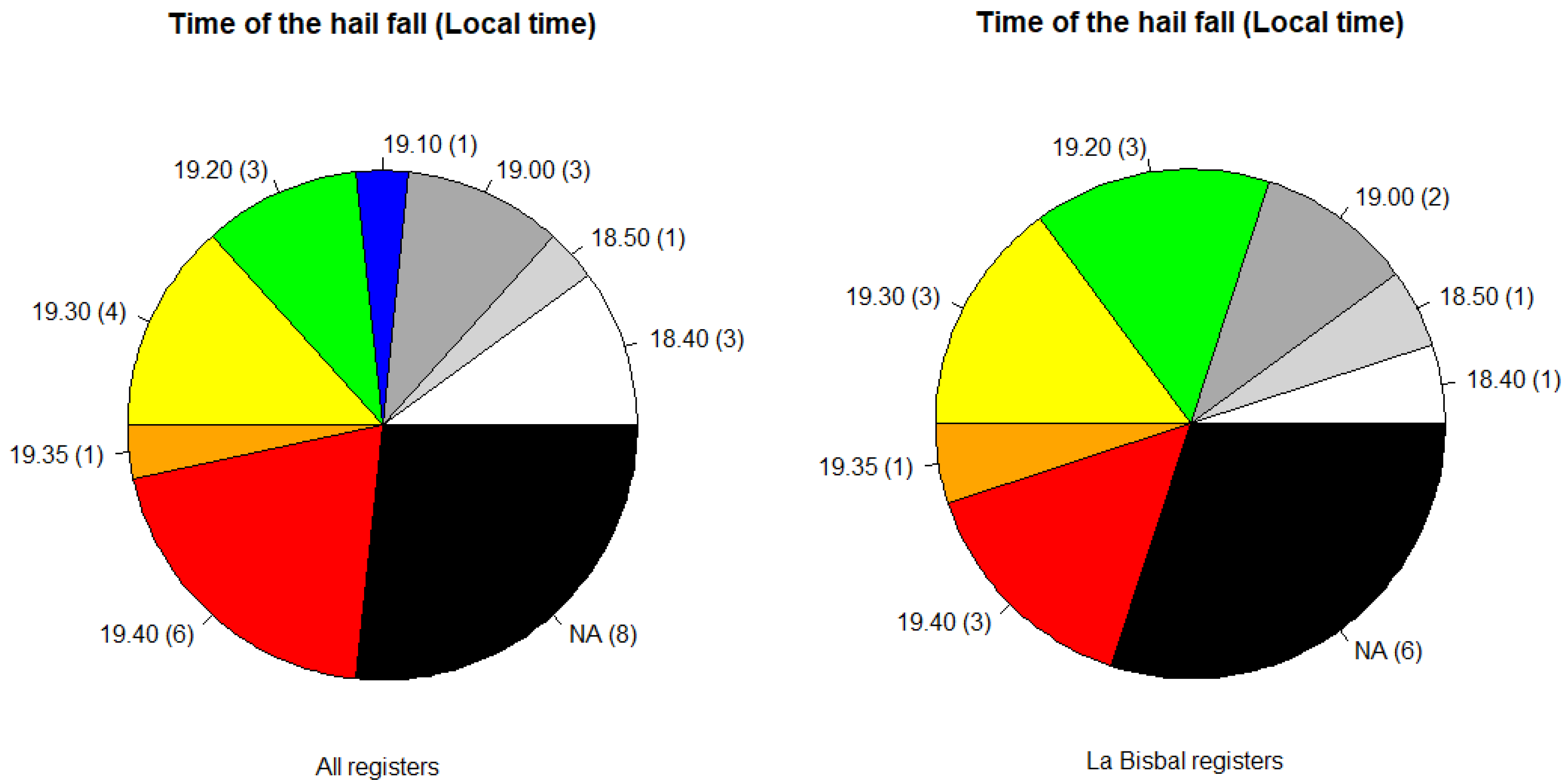

3.1.1. Time of Occurrence of the Event

The first question asked was at what time did occur the hailfall. Not all the registers correspond to the indicated coordinates. If we mark La Bisbal d’Empordà as the epicentre of the event, we can define as the origin the coordinates of the city centre: 41.959012

N, 3.037783

E. The highest points and lowest latitudes were 17 km North and 5 km South, respectively, while the extreme longitude registers were 5 km West and 10 km East. All the observations are integrated into the box (see

Figure 4).

Figure 5 shows the pie charts of the time of occurrence of the hail fall, according to the different answers to the survey. The left panel shows the results for all the collected cases, while the right focuses exclusively on the registers in the epicentre. According to the radar imagery, the thunderstorm hit the area shown in the right panel of

Figure 4 between 17.00 and 18.00 UTC (19.00 and 20.00 Local Time) and La Bisbal between 17.30 and 17.40 UTC (19.30 and 19.40 LT). One of the interesting points is that many observers in La Bisbal provided the wrong time: only seven of the fourteen registers agree with the radar observations. The difference in time between the event and the answer to the form can cause the discrepancy between radar and ground. In any case, this is the most difficult to answer because of the lag time, because it needs a conscience of time that is difficult to apply in events as analyzed. Furthermore, the observer should provide the answer in this case without any help. On the contrary, they could choose between different possible responses to the rest of the questions.

3.1.2. Duration of the Event

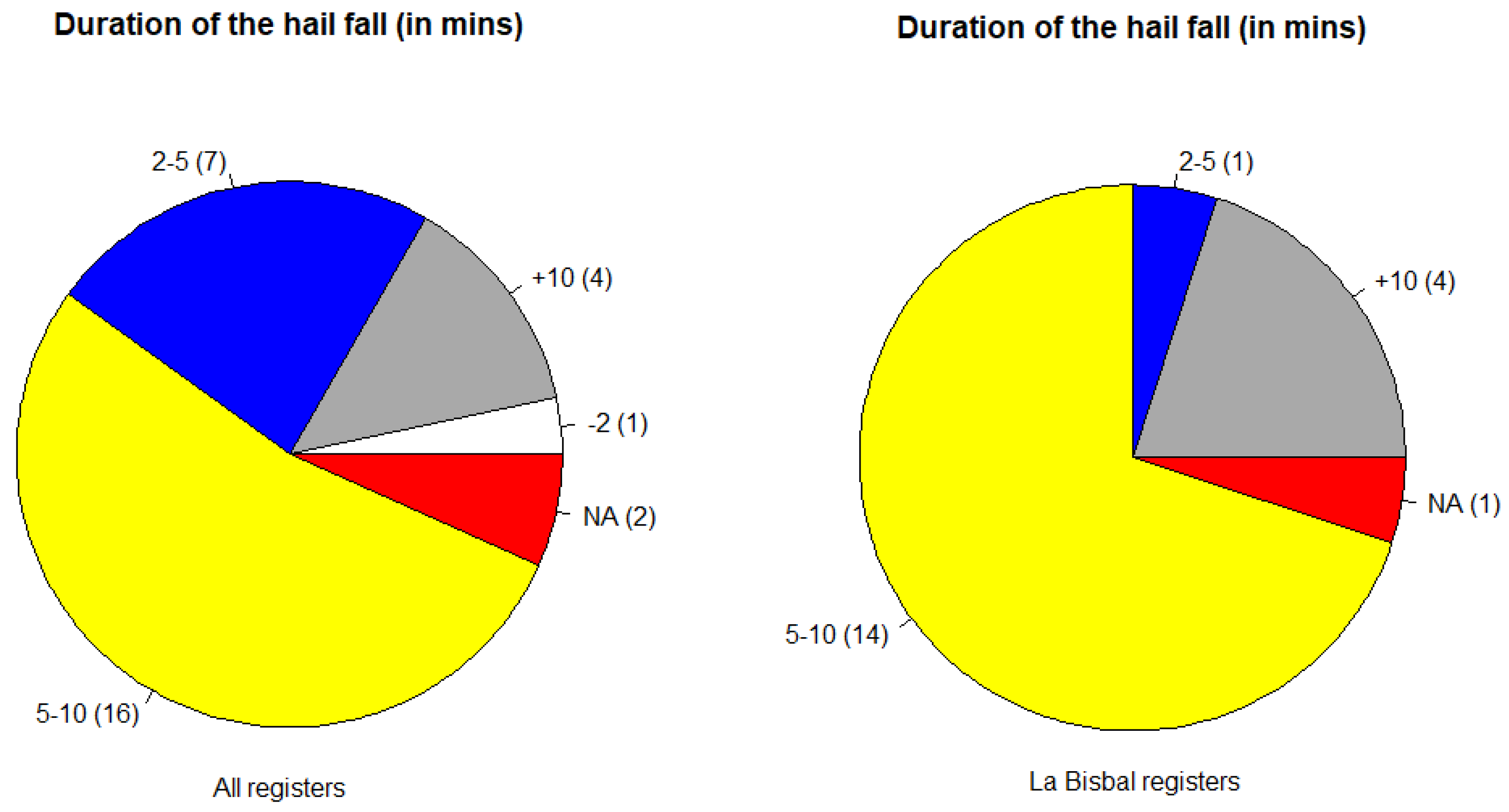

The second item of interest in the survey was the duration of the hail fall (

Figure 6). According to many testimonies interviewed by the television reporters on the same day of the event, the hail stones precipitated over La Bisbal for a very long time (some of the testimonies said: "It seemed that the hail did never stop to fall, and the size increased as the event evolved"). Then, the possible options were "less than 2 minutes", "between 2 and 5 minutes", "between 5 and 10 minutes", and "more than 10 minutes".

The event duration shows interesting information if we deepen the results. First, the case of reduced duration (less than 2 minutes) occurred far from the epicentre, the same that most of the observations of short duration (between 2 and 5 minutes). Only one testimony of the epicentre area provided one of the seven answers of short duration. Then, the percentage of cases of the short duration category moves from 23.3% (all registers) to only a 5% (La Bisbal registers). On the contrary, the percentage of registers of the category of long duration (between 5 and 10 minutes) increases from 53.3% of the whole area to 70% of the epicentre. Similar behaviour occurs with a very long duration category: all the cases were provided by La Bisbal testimonies, with a change from 13.3% to 20%.

The previous values agree with the radar fields, which indicate that the thunderstorm core crossed la Bisbal in the mature stage. On the contrary, the central part of the storm partially hit other populations or when it was in a less active phase. Searching for some comparable values in the bibliography, we only found the data provided by [

27] for the SW of France, who indicated values between 2 and 45 minutes, with a mean duration of 11.5 minutes (but for stones of less than 2 cm of diameter), or by [

28] for Switzerland, with 9 cases between 6 and 25 minutes of duration. Then, these results provide a first approach to the giant hail case duration.

3.1.3. Maximum Size of the Stones and Homogeneity

We have merged two questions (which was the maximum size of the stones? and "Were the stones of similar size?") in the same item: which was the behaviour of the hailfall? Besides asking for some testimonies during the fieldwork, we realized that other points were also important. One of them was how the event evolved. In all the reports, the description was the same: the episode started with large hailstones falling separated in time (some seconds) and space (about ten meters), passing to frequencies of less than one second and very close stones in the mid-part of the event. Besides, the hailfall was mostly dry (without liquid rainfall), except at the end.

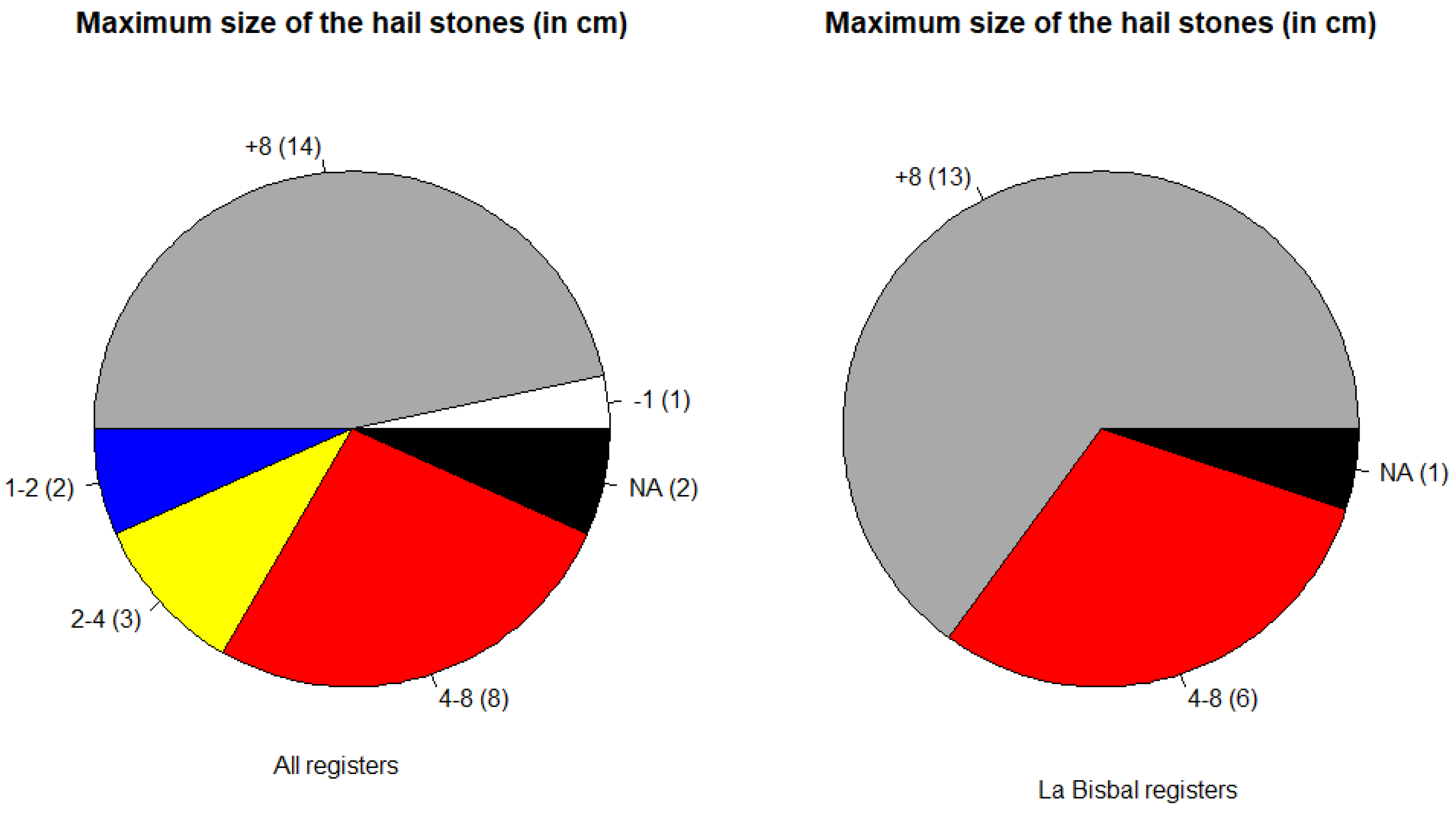

Moving to the maximum size,

Figure 7 summarizes the differences between all the regions and the focus on the epicentre. In the second case, there are only registers over 4 cm, but 65% of the testimonies indicated that larger hail stones exceeded the diameter of 8 cm. On the contrary, 20% of the cases in the total area had maximum sizes below 4 cm (including La Bisbal values). Then, we can affirm that existed a homogeneity in the occurrence of giant hail in the event epicentre, but this disappeared as the storm was far from La Bisbal. However, this point is different to the question about the variability of the size of the stones at a location (are all of them of a similar size at that point during all the events?). Only two testimonies of La Bisbal and two others from the rest of the area answered positively to that question. Surprisingly, in the case of the epicentre, both observers reported sizes of more than 8 cm (then, they affirmed that hail was of that size during the event), while in the other two cases, the maximum hail reported was of less than one and between 2 and 4 cm, respectively. In any case, most of the testimonies confirmed the heterogeneity of the stones’ size, agreeing with the previous analysis, as [

29].

3.2. Map of Maximum Size

Following the research done in [

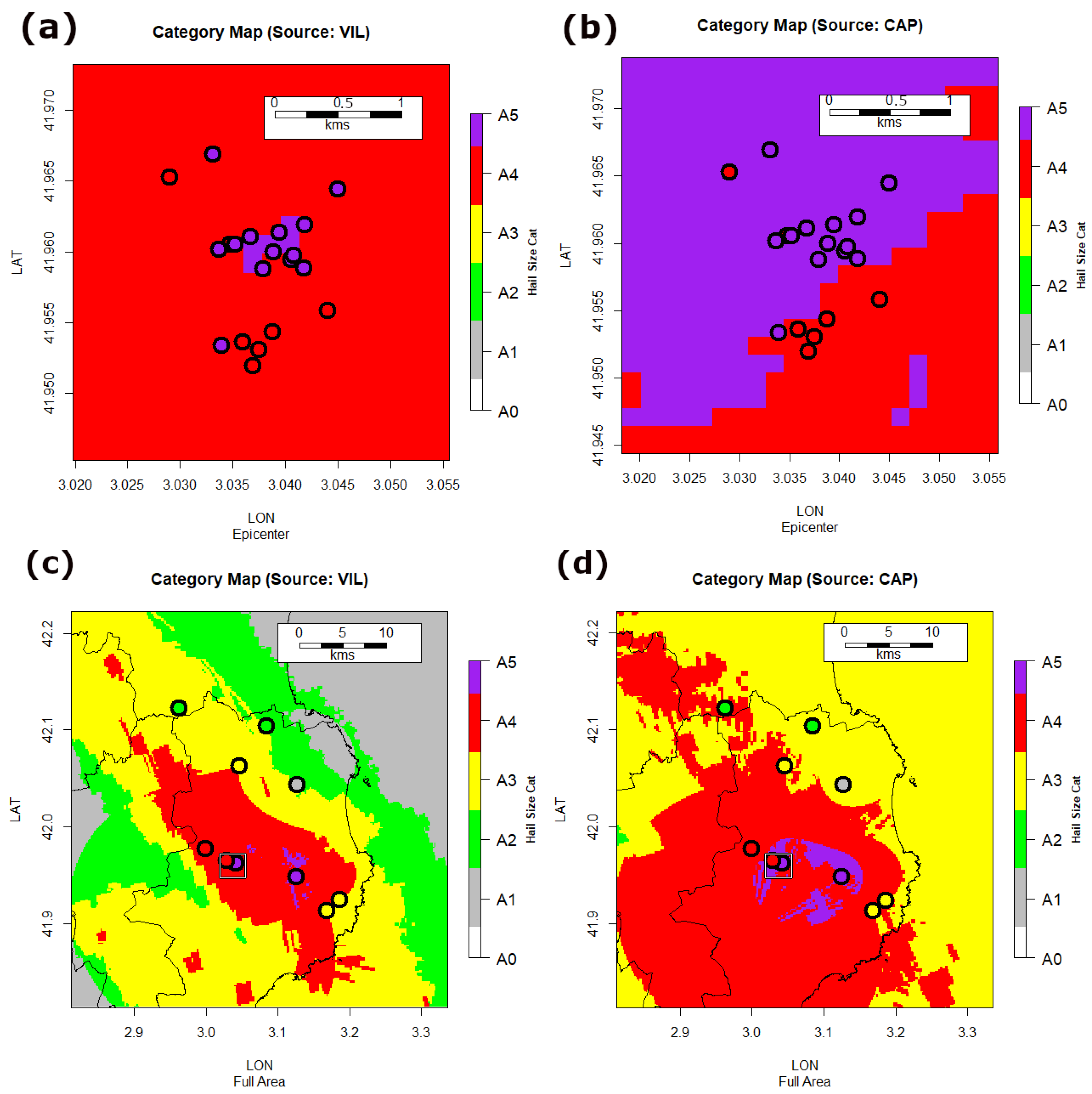

11], we have tried to estimate the field of the maximum size of the stones, combining the radar information and the ground registers. The combination technique consists of geo-statistical methods, in which the radar field provides the shape of the new map while the reports give quantitative information. As in the previous research, the universal co-kriging is the selected interpolation technique.

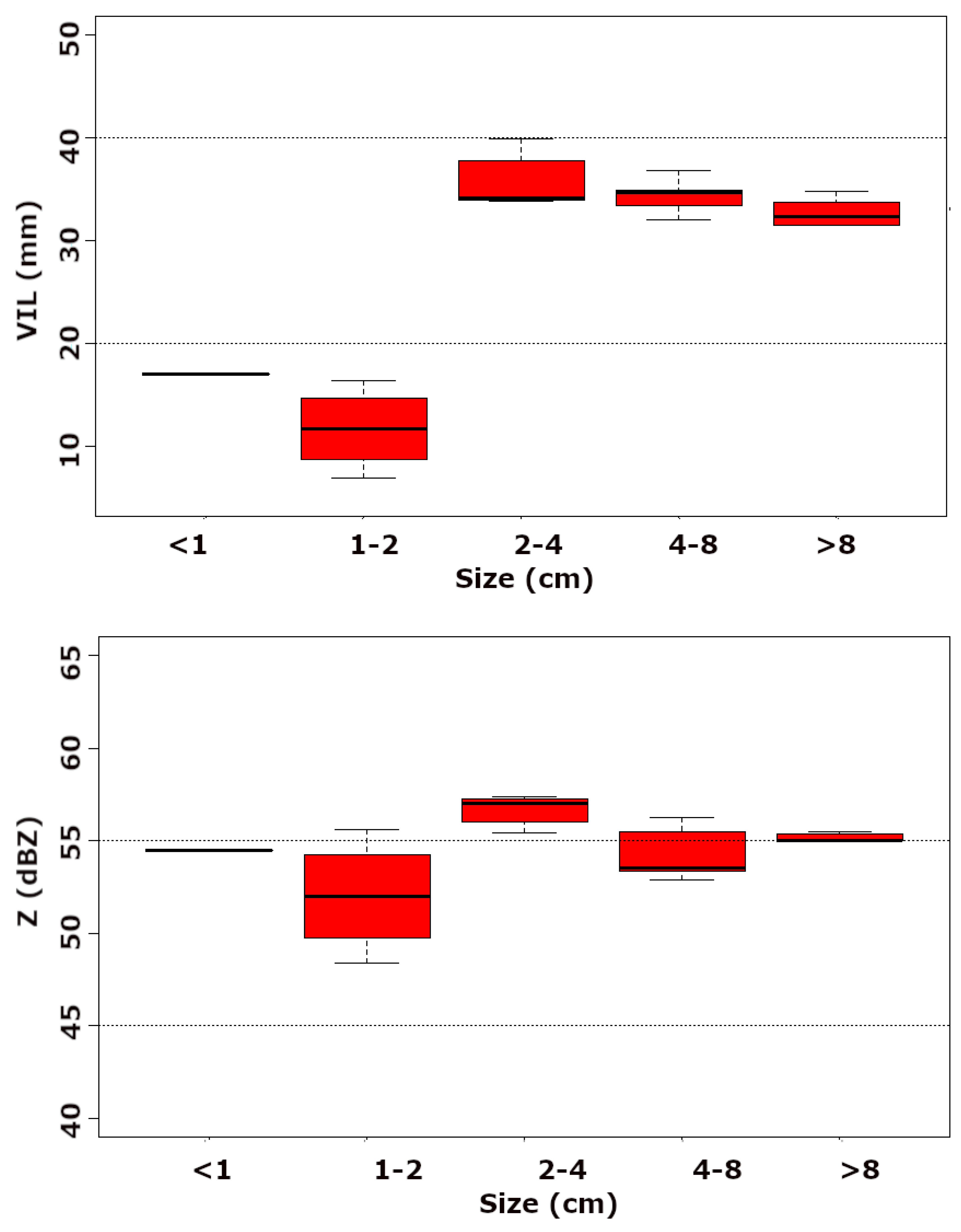

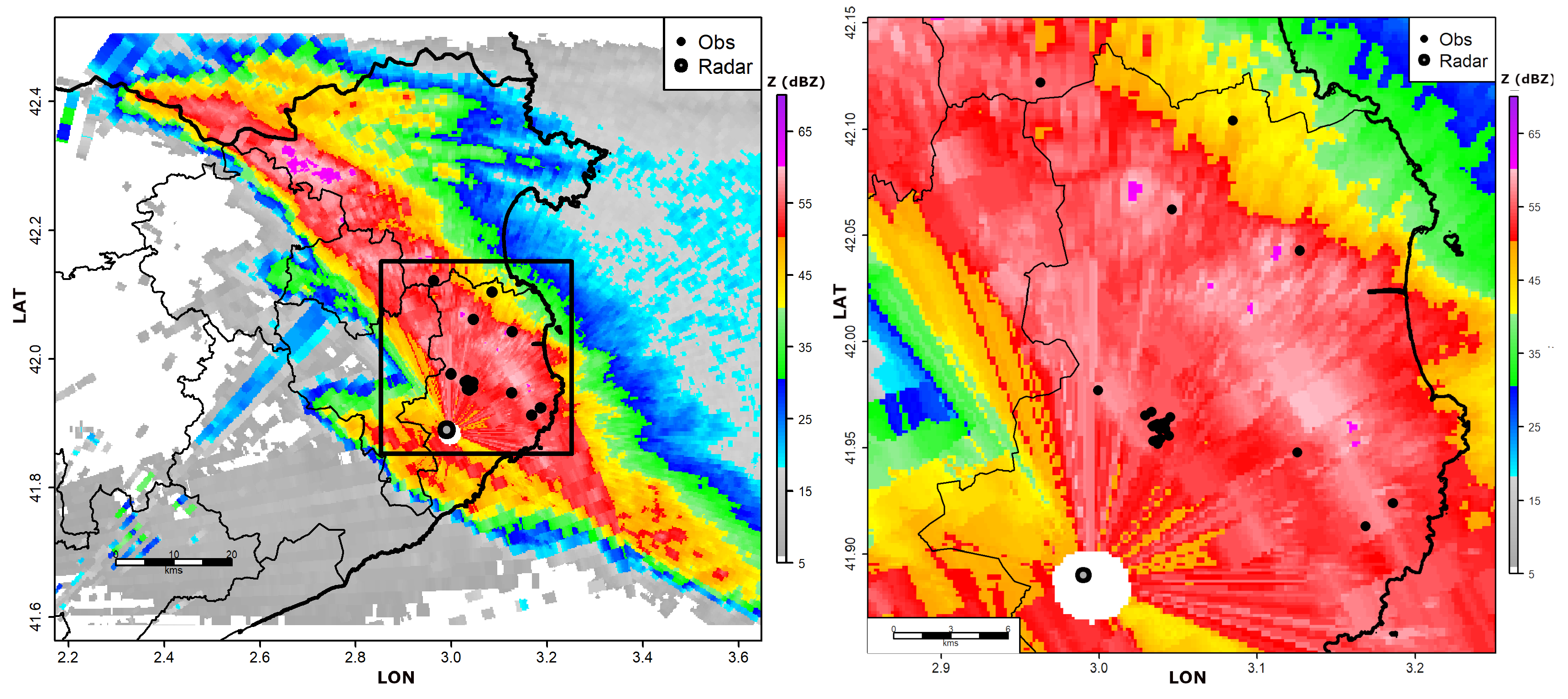

In the previous analysis, the radar field that fitted better was the VIL. However, there is a coherence lack of the product concerning the ground registers, looking to

Figure 4. The values in the epicentre (hail diameter larger than 8 cm) are lower than 40 mm, while in other regions with lower values of the hail size, the VIL exceeds 55 mm (

Figure 8). The causes of these anomalies are: first, the distance of most of the radars to the area of interest (more than 100 km except for PDA -Puig d’Arques- radar), making their contribution poor. Second, the thunderstorm moved quasi-perpendicular to the PDA radar, affecting the higher levels when the cloud was too close to the radar (less than 20 km). These first two causes are associated with the same product configuration, which is highly dependent on the vertical profile of reflectivity at each point [

30]. Then, Finally, the attenuation of the radar signal caused by the large hail, agreeing with the observations of [

31].

To minimize the previous limitations, and following the proposal of [

11], we have selected the maximum reflectivity field as the radar predictor field. In this case, the maxim daily map (

Figure 9) and the boxplots (bottom panel of

Figure 8) are more coherent with the ground registers. This coherence appears in the epicentre of the event, where the values of the reflectivity are more in agreement with the ground observations than VIL, and with the evolution of the boxplot categories: the larger hail stone registers (8 cm) presented at least similar values than other categories (2-4 cm or 4-8 cm).

Figure 10 presents the results of applying the Universal Co-Krigging technique. The top panels (a and b) show the results for the event epicentre, using as predictors the VIL and the maximum reflectivity, respectively. The first radar product cannot reproduce the nature of the hailfall, reducing the area of giant hail (A5) to the event epicentre (La Bisbal). On the contrary, the area with large hailstones over 8 cm estimated using maximum reflectivity seems over-sizing, according to the ground observations. Similar behaviour occurs for the total hit area (panels c and d), with a sub-estimation for the VIL product and an over-estimation for maximum reflectivity. However, both fields allow the understanding of the nature of the hail-swath and can help to identify areas of affectation of different nature (e.g. in pine forest [

32]).

3.3. Comparison between Observations and Radar Fields

The last part of the research compared the information provided by the two sources: direct observations from the electronic survey, and the VIL radar field, over the locations of the ground registers. We first studied the differences between the time provided by the observers and the one when VIL was not null over the same point. In this case, the radar acted as the observation. Second, we have compared the VIL values over the location and the maximum size observed at the ground. Here the reports have been considered as ground truth. Before introducing the analysis, it is worth considering the different issues that could affect the results:

- •

the survey was made three months later, affecting the memory capacity of the contributors, in special at the time of occurrence. However, this lag helped to minimize the effect of exaggeration of the hail size.

- •

VIL radar product was affected by different constraints presented previously: signal attenuation and distance of the hailstorm to the radars, among others.

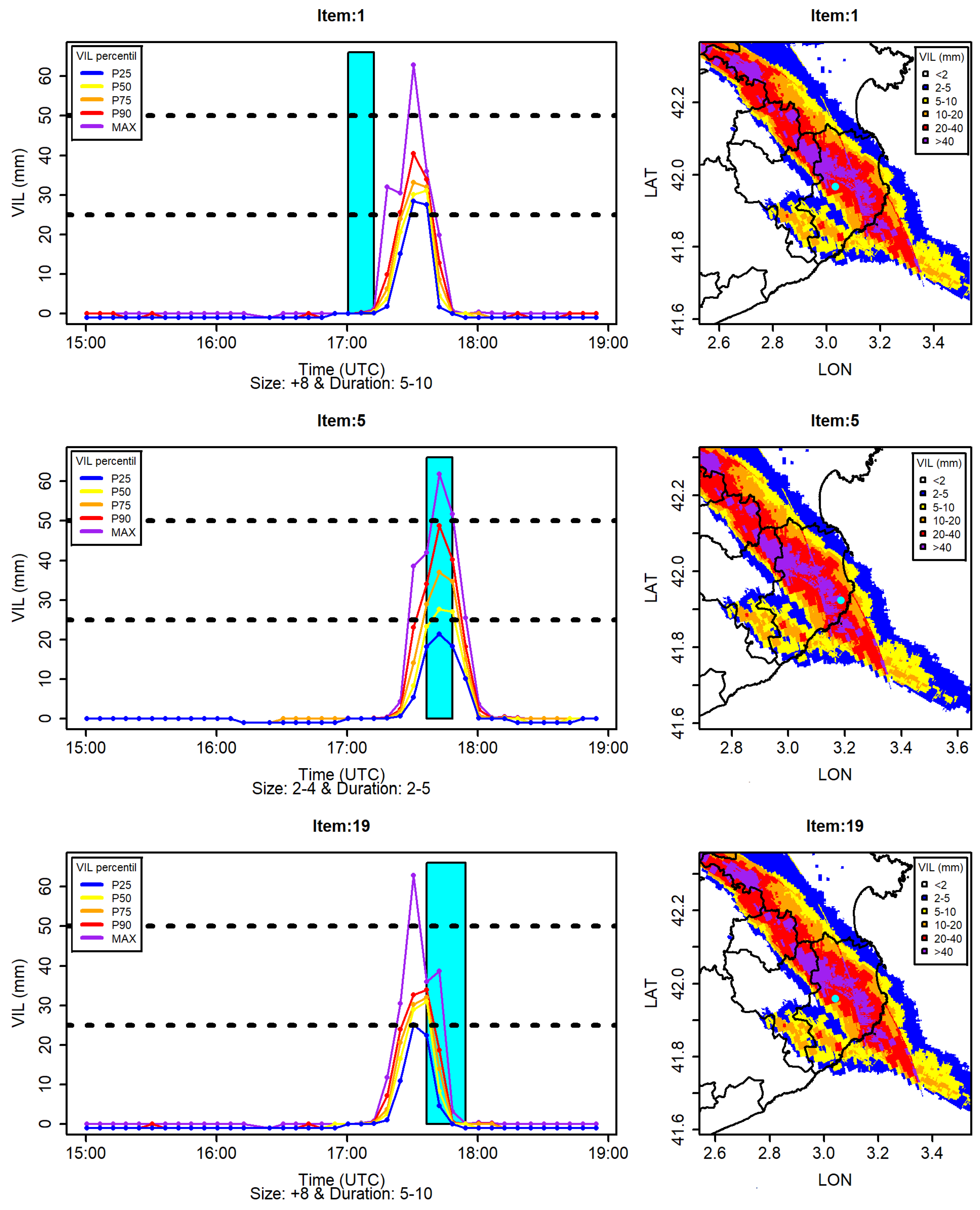

Figure 11 shows three examples of the different behaviours observed concerning the time lag between the survey and the radar: (top) a case when the observation (cyan rectangle) in the survey was before the real-time occurrence (based on the radar information); (centre) an example where the survey register and the radar field are simultaneous; (below) the time observer was delayed respect on the radar data. These differences are mainly due to the time between the event and the survey. The VIL percentiles (25 in blue, 50 in yellow, 75 in orange, 90 in red and max in purple) were estimated from all the pixels surrounding the coordinates provided by the observer in a radius of 2.5 km. The right column presents the location of the survey observations for each case (cyan point in the centre of each map). The top and bottom panels correspond to observations close in space, but one provided a 30-minute advanced time, while the other gave a 30-minute delayed time.

Table 1 and

Table 2 summarize the two points of interest. The first shows the difference between the survey estimation of the time of occurrence and the radar data. We have considered the three options: advanced, synchronized, and delayed. 12 of the 20 valid observations (60%) were in time, indicating that most observers remembered the event evolution. From the out-of-time registers, most of them were ahead of time (6, a 30% of the total), with a mean difference of 33 minutes. On the opposite, only 2 (10%) cases were delayed, with a mean difference of 10 minutes (clearly lower than the advanced cases). This behaviour had similitude with the one for the epicentre region, but the time error was larger than the global.

About the capability of a good size estimation through the VIL evolution, the previous section showed the limitations of the radar product. In the same way,

Table 2 confirms the same performance for the individual observations. The underrating is clear for all the cases except one in the epicentre (13 of 14, which is a 65% of the total). On the contrary, the behaviour is quite good (3 right performances and three overrating) for the rest of the regions, where the observations were lower (from less than 1 cm to between 4 and 8 cm). This fact confirms that the C-Band has high limitations in the cases of giant (and even large) hail because of the beam signal attenuation. Besides, the proximity of the radar was not enough to minimize limitations.

4. Discussion

This research has focused on comparing two different data sources to determine their ability to explain some characteristics of the giant hail event of 30 August 2022 in La Bisbal d’Empordà (NE of Catalonia). The data sources are the results of an electronic survey, on the one hand. On the other hand, the maximum daily reflectivity and VIL composite radar parameters, with a spatial resolution of 150 m X 150 m and a time resolution of 6 minutes. We made the e-survey three months after the event to avoid the hail size exaggeration, which is one of the issues from direct visual estimations [

33]. The questions included in the survey were:

Can you provide the exact location where did you live at the event?

What was the time of occurrence of the event?

How much time did it last?

Which was the maximum size observed?

Were all the stones similar in size?

The results of the survey seem of high quality, except for the point of the time of occurrence. The comparison with the evolution of the radar fields shows how some observers provided an advanced time (∼35 minutes on average) while others gave delayed times (∼10 minutes on average). On the opposite, sizes were quite consistent with the evolution of the episode and the data provided by the official spotters of the SMC.

On the other hand, the radar fields (VIL and maximum reflectivity) allowed us to determine the temporal evolution of the event over each location but, on the contrary, suffered limitations in the size estimation. The fact that the sizes were more than 8 cm in a lot of places and the proximity to one of the C-band single-pol radars (which cannot contribute to a part of the event because the radar volume was limited) agree with previous research [

18], [

30], or [

31]. Because of these limitations, it was impossible to reproduce an estimated field combining both sources through geostatistical analysis (Universal Co-Kriging) in a similar way that the used in Catalonia for previous events [

11].

5. Conclusions

To sum up, the main conclusions of the analysis have been:

The combination of observational data provided using e-survey and some radar fields allows a better understanding of different elements of the evolution of a giant hail event,

The observations at the ground gave a better estimation of the size,

The weather radar helps to have a better understanding of the evolution,

However, it was not possible to generate a maximum hail size field combining both data because of the limitations of the weather radar in this type of giant hail size.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.R. and C.F.; methodology, T.R. and C.F.; software, T.R.; validation, C.F.; formal analysis, T.R.; investigation, T.R. and C.F.; resources, T.R. and C.F.; data curation, T.R.; writing—original draft preparation, T.R.; writing—review and editing, T.R. and C.F.; visualization, T.R.; supervision, C.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon via e-mail request.

Acknowledgments

The Authors want to thank all the people of La Bisbal d’Empordà and the surroundings towns who contributed to the Research with their testimony and, in some cases, with frozen hails. In special, we want to thank Angel Galan for managing all the preliminary process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VIL |

Vertical Integrated Liquid |

| XRAD |

Radar Network of the Servei Meteorològic de Catalunya |

| UTC |

Coordinated Universal Time |

| LT |

Local Time |

| PDA |

Puig d’Arques Radar |

References

- Rigo, T.; Rius, A. Inform about the estimation of the hit area by the hailstorm of the (in Catalan). Technical Report., 2022. Accessed December, 2022. 30 August.

- Pucik, T. On the predictability of the giant hail event in Catalonia, 2022. Accessed December, 2022.

- Aran, M.; Pena, J.; Torà, M. Atmospheric circulation patterns associated with hail events in Lleida (Catalonia). Atmos. Res. 2011, 100, 428–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aran, M.; Sairouni, A.; Bech, J.; Toda, J.; Rigo, T.; Cunillera, J.; Moré, J. Pilot project for intensive surveillance of hail events in Terres de Ponent (Lleida). Atmos. Res. 2007, 83, 315–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girona, J.; Behboudian, M.; Mata, M.; Del Campo, J.; Marsal, J. Effect of hail nets on the microclimate, irrigation requirements, tree growth, and fruit yield of peach orchards in Catalonia (Spain). J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2012, 87, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnell, C.; Llasat, M.d.C. Proposal of three thermodynamic variables to discriminate between storms associated with hail and storms with intense rainfall in Catalonia. Tethys 2013, 10, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnell, C.; Rigo, T.; Heymsfield, A. Shape of hail and its thermodynamic characteristics related to records in Catalonia. Atmos. Res. 2022, 271, 106098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigo, T.; Farnell Barqué, C. Evaluation of the Radar Echo Tops in Catalonia: Relationship with Severe Weather. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnell, C.; Rigo, T. The Lightning Jump, the 2018 “Picking up Hailstones” Campaign and a Climatological Analysis for Catalonia for the 2006–2018 Period. Tethys 2020, 17, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnell, C.; Rigo, T.; Pineda, N.; Aran, M.; Busto, M.; Mateo, J. The different impact of a severe hailstorm over nearby points. European Conference on Severe Storms, Helsinki, 2013, pp. 3–7.

- Farnell, C.; Rigo, T.; Martin-Vide, J. Application of cokriging techniques for the estimation of hail size. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2018, 131, 133–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermida, L.; Sánchez, J.L.; López, L.; Berthet, C.; Dessens, J.; García-Ortega, E.; Merino, A. Climatic trends in hail precipitation in France: Spatial, altitudinal, and temporal variability. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcos, J.; Sánchez, J.; Merino, A.; Melcón, P.; Mérida, G.; García-Ortega, E. Spatial and temporal variability of hail falls and estimation of maximum diameter from meteorological variables. Atmos. Res. 2021, 247, 105142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalezios, N.R.; Loukas, A.; Bampzelis, D. Universal kriging of hail impact energy in Greece. Phys. Chem. Earth, Parts A/B/C 2002, 27, 1039–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.T.; Giammanco, I.M.; Kumjian, M.R.; Jurgen Punge, H.; Zhang, Q.; Groenemeijer, P.; Kunz, M.; Ortega, K. Understanding hail in the earth system. Rev. Geophys. 2020, 58, e2019RG000665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnell, C.; Busto, M.; Aran, M.; Andrés, A.; Pineda, N.; Torà, M. Study of the hailstorm of 17 September 2007 at the Pla d’Urgell. Part one: Fieldwork and analysis of the hailpads. Tethys 2009, 6, 69–81. [Google Scholar]

- Rigo, T.; Farnell, C. Using maximum Vertical Integrated Liquid (VIL) maps for identifying hail-affected areas: An operative application for agricultural purposes. J Mediterr. Meteorol Clim. 2019, 16, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, S.F.; Deroche, D.R.; Boustead, J.M.; Leighton, J.W.; Barjenbruch, B.L.; Gargan, W.P. A radar-based assessment of the detectability of giant hail. E-J. Sev. Storms Meteorol. 2011, 6, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, A.; Burgess, D.W.; Seimon, A.; Allen, J.T.; Snyder, J.C.; Bluestein, H.B. Rapid-scan radar observations of an Oklahoma tornadic hailstorm producing giant hail. Weather Forecast. 2018, 33, 1263–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, R.E.; Kumjian, M.R. Environmental and radar characteristics of gargantuan hail–producing storms. Mon. Weather Rev. 2021, 149, 2523–2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumjian, M.R.; Gutierrez, R.; Soderholm, J.S.; Nesbitt, S.W.; Maldonado, P.; Luna, L.M.; Marquis, J.; Bowley, K.A.; Imaz, M.A.; Salio, P. Gargantuan hail in Argentina. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 101, E1241–E1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montopoli, M.; Picciotti, E.; Baldini, L.; Di Fabio, S.; Marzano, F.; Vulpiani, G. Gazing inside a giant-hail-bearing Mediterranean supercell by dual-polarization Doppler weather radar. Atmos. Res. 2021, 264, 105852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papavasileiou, G.; Kotroni, V.; Lagouvardos, K.; Giannaros, T.M. Observational and numerical study of a giant hailstorm in Attica, Greece, on 4 October 2019. Atmos. Res. 2022, 278, 106341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cintineo, J.L.; Smith, T.M.; Lakshmanan, V.; Brooks, H.E.; Ortega, K.L. An objective high-resolution hail climatology of the contiguous United States. Weather Forecast. 2012, 27, 1235–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmore, K.L.; Allen, J.T.; Gerard, A.E. Sub-Severe and Severe Hail. Weather Forecast. 2022, 37, 1357–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, S.S.; Blong, R.J.; Speer, M.S. A hail climatology of the greater Sydney area and New South Wales, Australia. Int. J. Climatol. A J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2005, 25, 1633–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessens, J. Hail in southwestern France. I: Hailfall characteristics and hailstrom environment. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 1986, 25, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohl, R.; Schiesser, H.H.; Aller, D. Hailfall: The relationship between radar-derived hail kinetic energy and hail damage to buildings. Atmos. Res. 2002, 63, 177–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sioutas, M.; Meaden, T.; Webb, J.D. Hail frequency, distribution and intensity in Northern Greece. Atmos. Res. 2009, 93, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudevillain, B.; Andrieu, H. Assessment of vertically integrated liquid (VIL) water content radar measurement. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2003, 20, 807–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltenboeck, R.; Ryzhkov, A. Comparison of polarimetric signatures of hail at S and C bands for different hail sizes. Atmos. Res. 2013, 123, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballol, M.; Méndez-Cartín, A.L.; Serradó, F.; De Caceres, M.; Coll, L.; Oliva, J. Disease in regenerating pine forests linked to temperature and pathogen spillover from the canopy. J. Ecol. 2022, 110, 2661–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopp, J.; Schröer, K.; Schwierz, C.; Hering, A.; Germann, U.; Martius, O. The summer 2021 Switzerland hailstorms: Weather situation, major impacts and unique observational data. Weather 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Area hit by the hailstorm of the 30 August 2022. The green pins indicate the locations of the three points of the field work, the orange points show the positions with information provided thorough the electronic form, and the solid lines delimit the areas of Vertical Integrated Liquid (VIL) from radar of 15 mm (orange), 35 mm (red) and 55 mm (purple). The top-right panel marks the area (white rectangle) in the Europe map.

Figure 1.

Area hit by the hailstorm of the 30 August 2022. The green pins indicate the locations of the three points of the field work, the orange points show the positions with information provided thorough the electronic form, and the solid lines delimit the areas of Vertical Integrated Liquid (VIL) from radar of 15 mm (orange), 35 mm (red) and 55 mm (purple). The top-right panel marks the area (white rectangle) in the Europe map.

Figure 2.

Zoom to La Bisbal d’Empordà (marked with a red line) and Corçà (delimit by a blue line) populations. The green pins correspond to the locations of the field work and the orange points mark the positions with information provided in the form.

Figure 2.

Zoom to La Bisbal d’Empordà (marked with a red line) and Corçà (delimit by a blue line) populations. The green pins correspond to the locations of the field work and the orange points mark the positions with information provided in the form.

Figure 3.

Above: Track of the hailstorm delimited by the purple solid lines. The yellow line indicates the section of the vertical profile of the elevation. Below: Vertical profile of the elevation.

Figure 3.

Above: Track of the hailstorm delimited by the purple solid lines. The yellow line indicates the section of the vertical profile of the elevation. Below: Vertical profile of the elevation.

Figure 4.

Left: Maximum daily VIL field (in mm) of the event. The black dots correspond to the registers and the largest black and grey dot indicates the location of the closest radar. Below: Zoom to the region with registers, corresponding to the black square in the left panel.

Figure 4.

Left: Maximum daily VIL field (in mm) of the event. The black dots correspond to the registers and the largest black and grey dot indicates the location of the closest radar. Below: Zoom to the region with registers, corresponding to the black square in the left panel.

Figure 5.

Left: Pie chart with the time (local time, +2 hours respect the UTC) of all the registers. Right: The same as the left panel, but only for La Bisbal de l’Empordà cases.

Figure 5.

Left: Pie chart with the time (local time, +2 hours respect the UTC) of all the registers. Right: The same as the left panel, but only for La Bisbal de l’Empordà cases.

Figure 6.

As the

Figure 5, but for the duration of the event.

Figure 6.

As the

Figure 5, but for the duration of the event.

Figure 7.

As the

Figure 5, but for the maximum size of the stones.

Figure 7.

As the

Figure 5, but for the maximum size of the stones.

Figure 8.

Boxplot of the different sizes for the VIL (above) and the maximum reflectivity (below) daily fields.

Figure 8.

Boxplot of the different sizes for the VIL (above) and the maximum reflectivity (below) daily fields.

Figure 9.

As the

Figure 4, but for the maximum reflectivity.

Figure 9.

As the

Figure 4, but for the maximum reflectivity.

Figure 10.

Maximum hail size field obtained from Universal Co-Krigging: (a) Using VIL for the epicenter; (b) Using Maximum reflectivity for the epicenter; (c) as (a) for the full area; (d) as (b) for the full area. A0 indicates "No hail", A1 "hail ≤1 cm", A2 "hail 1-2 cm", A3 "hail 2-4 cm", A4 "hail 4-8 cm", and A5 "hail ≥8 cm".

Figure 10.

Maximum hail size field obtained from Universal Co-Krigging: (a) Using VIL for the epicenter; (b) Using Maximum reflectivity for the epicenter; (c) as (a) for the full area; (d) as (b) for the full area. A0 indicates "No hail", A1 "hail ≤1 cm", A2 "hail 1-2 cm", A3 "hail 2-4 cm", A4 "hail 4-8 cm", and A5 "hail ≥8 cm".

Figure 11.

Different behaviors between VIL and the electronic survey. Left column: VIL evolution of the percentiles 25, 50, 75 and 90, and the maximum over the location (cyan point on the right column maps). The cyan rectangles indicate the hail time (provided by the survey). The size and the duration are shown below the X-axis label "Time (UTC)". Right column: Maps showing the maximum daily VIL field in the surrounding of each observation. Top: the survey indicated that the event occurred before the real time. Middle: a case of simultaneity. Below: a case of delay of the observation.

Figure 11.

Different behaviors between VIL and the electronic survey. Left column: VIL evolution of the percentiles 25, 50, 75 and 90, and the maximum over the location (cyan point on the right column maps). The cyan rectangles indicate the hail time (provided by the survey). The size and the duration are shown below the X-axis label "Time (UTC)". Right column: Maps showing the maximum daily VIL field in the surrounding of each observation. Top: the survey indicated that the event occurred before the real time. Middle: a case of simultaneity. Below: a case of delay of the observation.

Table 1.

Number of cases of each behavior time of observation (survey) respecting on the real-time (weather radar). The numbers in the parentheses indicate the cases in the Epicenter.

Table 1.

Number of cases of each behavior time of observation (survey) respecting on the real-time (weather radar). The numbers in the parentheses indicate the cases in the Epicenter.

| |

Advanced |

Synchronized |

Delayed |

| N cases |

6 (4) |

12 (8) |

2 (2) |

Table 2.

Number of cases of each behavior size of observation (weather radar) respecting on the real size (survey). The numbers in the parentheses indicate the cases in the Epicenter.

Table 2.

Number of cases of each behavior size of observation (weather radar) respecting on the real size (survey). The numbers in the parentheses indicate the cases in the Epicenter.

| |

Underrated |

Right |

Overrated |

| N cases |

13 (13) |

4 (1) |

3 (0) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).