Submitted:

02 June 2023

Posted:

05 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The EU and ASEAN

2.1. The EU as a Regional Organisation

- (1)

- Supporting arguments: EVG would create provision for closer co-operation between those counties that wish for greater progress on certain issues connected with closer integration.

- (2)

- Opposing arguments: factions that develop within EVG can result in a “vanguard of countries” the intention of which is to face up to the reality of an enlarged Europe without reference to the conflicts of the constitutional Treaty.

- Decline of German economic power after the union with East Germany following the collapse of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

- Widespread German questioning of its ‘social-market’ model in the face of globalisation and resurgent Anglo-Saxon economic challenges.

- Economic development of the UK.

- Rapid substitution of French by English as the dominant language of the EU with the joining of the Nordic and CCEE nations.

2.2. ASEAN as a Regional Organisation

- (a)

- economic development plans

- (b)

- conflicts over border demarcations

- (c)

- problems with minorities within countries and border areas

- (d)

- human rights development

- (e)

- democratic development

2.3. Relating ASEAN and the EU

2.3.1. Similarities and Differences between the EU and ASEAN

2.3.2. Regionalism and Regionalisation

- Regionalism: a political will to create a formal arrangement among states on a geographically restricted basis. Since its main participants are governments, it can be expressed as an artificial, top-down process. Regionalism when in process refers to the agreement of regionally close governments to establish kinds of formal institutions, and it is characterised by preferential trade agreements.

- Regionalisation: an increase in the cross-border flow of capital, goods, and people within a specific geographical area that is a spontaneous bottom-up process and societally driven through markets, private trade, and investment flows, none of which is strictly controlled by governments. Core players are non-governmental actors, like firms or individuals. The development of regionalisation results in an increase in the number of regional economic transactions, like money, trade, and foreign direct investment, and it can be characterized by trade and foreign direct investment.

3. The Social Organisation of ROs – the Pragmatics of ASEAN with Comparative EU Reference

3.1. The Gemeinschaft-Gesellschaft Paradigm

3.1.1. The Natures of Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft

3.1.2. The Tönnies-Triandis Connection

3.2. Collective Action in the EU and ASEAN

4. Modelling Regional Organisations

4.1. The Modelling Underlay

4.2. Modelling the RO Agency

4.2.1. The CAT Model

4.2.2. The Intelligences

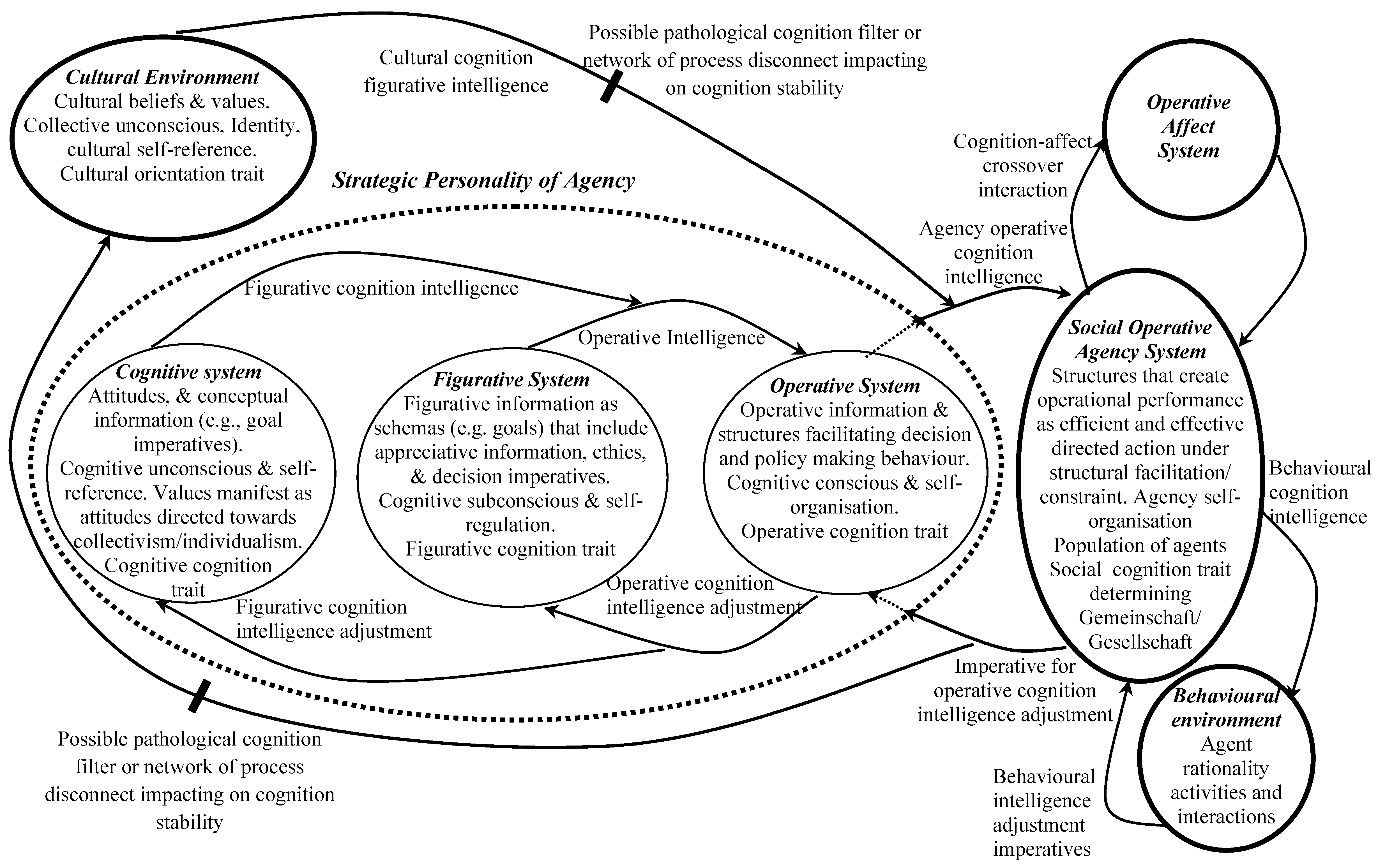

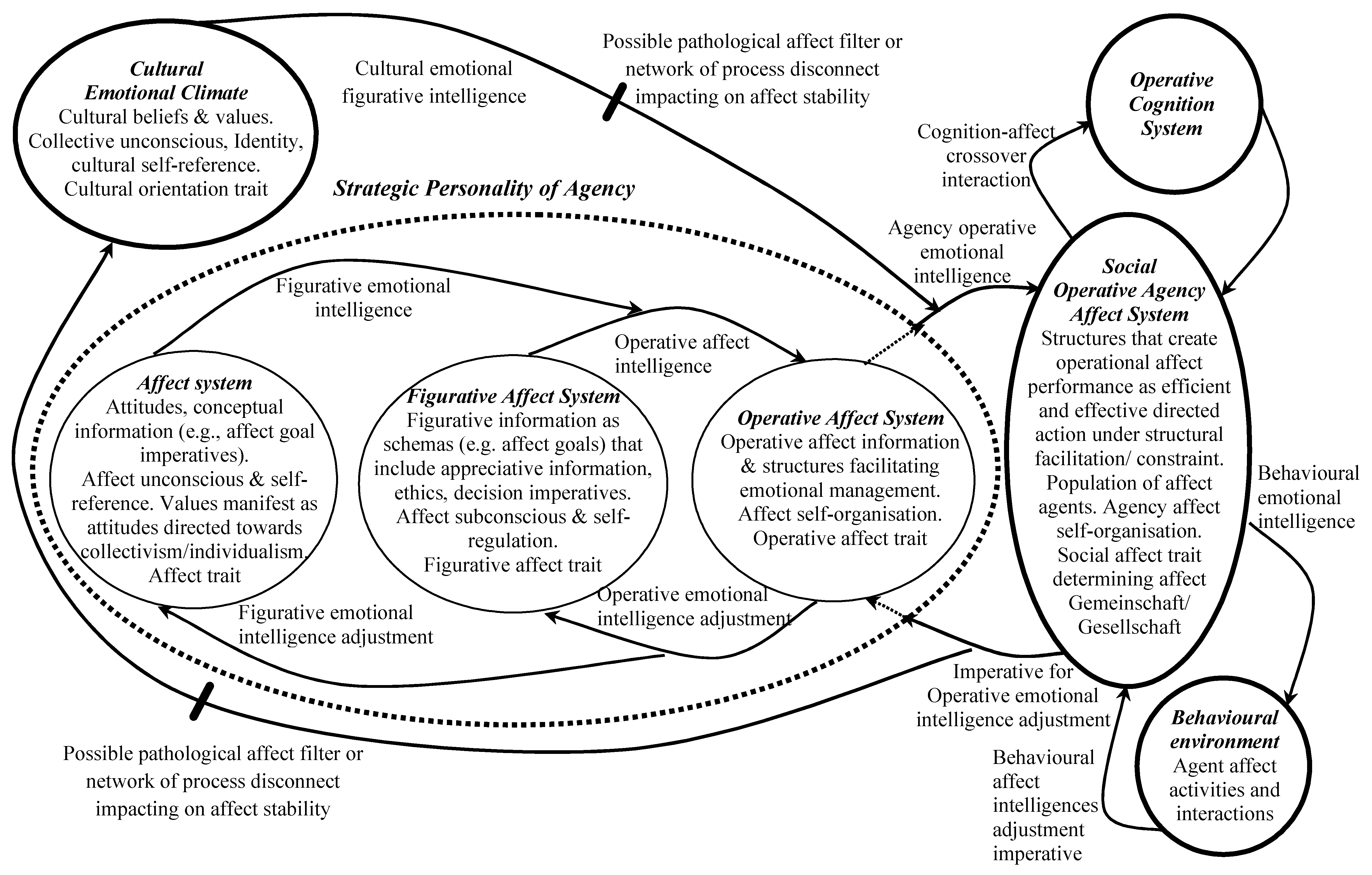

- Behavioural intelligence connects environmental parameters with the operative system. Its action enables the contextual and perhaps dynamic parameters in the environment to be identified, selected and measured. The intelligence structures the data used as a data model used for operations. The intelligence works in two directions, towards the environment where it informs agent behaviour, and towards the operative system where structured data can be updated.

- Operative intelligence enables autopoiesis (self-production through its network of processes) that connects the operative and figurative systems, where [227] autopoiesis services the processes of agency self-regulation. Structural information is acquired from the structure data deriving from the environment, and this is transformed autopoietically so that it can be referred to by the figurative system. Autopoietic circular causality occurs when the regulatory map is updated enabling new regulatory processes to arise, and an alternative flow can adjust the structured data model.

- Figurative intelligence enables autogenesis (self-creation). It acquires information from parameters in the agency personality, and it determines if there are any indications of instability in that personality. Where there are, it determines the causes and takes self-stabilising control action to correct this. The reverse action also occurs to enable adjustments.

4.3. From Traits to Mindsets

5. The ASEAN Mindset

- Agency cultural Ideationality: Idea-centred rather than pragmatic, unconditional morality, supporting tradition, a tendency toward idea creation, and self-examination self.

- Personality cognitive Intellectual Autonomy: Supports notions of autonomy/uniqueness among agents, expresses internal attributes (like feelings), and independently pursues ideas/intellectual directions.

- Personality figurative Harmony: As a pluralistic organisation, agents pursue their own ideas and intellectual directions independently, with mutual understanding and appreciation (not exploitation), unity with nature, and the world at peace.

- Personality operative Hierarchy: Power is hierarchical, normally unequally distributed, and supporting a chain of authority.

- Agency social operative Patterning: Social and other forms of relational configurations, social influence in dynamic relationships, persistent curiosity, symmetry, pattern, balance, and collective goal formation is important, as are subjective perspectives.

- Agency cultural emotional climate Missionary: the imposition of ideas on others, and idea converting, heralding, promoting, susceptible to propagandism and revivalism.

- Personality affect Containment: dependability, restraint, self-possession, self-containment, self-control, self-discipline, self-governance, self-mastery, self-command, moderateness and continence.

- Personality figurative Protection: safety, stability/security, protective shield, safety, conservation, insurance, preservation, safeguarding.

- Personality operative Dominance: control, domination, rules giving supremacy/hegemony, power, pre-eminence, sovereignty, ascendancy, authority, command, susceptibility to narcissism and vanity.

- Agency social operative Empathetic: accepting, compassionate, sensitive, sympathetic.

6. The Efficacy of ASEAN Performance and its Mindsets

6.1. ASEAN Culture

6.2. ASAN and its Agents

6.3. ASEAN Personality

6.4. The Failings of ASEAN Political Culture

6.5. The ASEAN Way as an Attitude

6.5. The Social Organisation/Structure of ASEAN

6.6. The Intelligences

6.7. ASEAN Instrumentality

6.8. The Lack of ASEAN Pragmatics in Dispute Settlement

7. General Discussion and Conclusions

8. Finale

References

- Alagappa, M., “Regionalism and conflict management: a framework for analysis,” in In M. Alagappa & M. Yoshitomi (Eds.), The changing regional security order in Asia: the role of the United States, Tokio, Japan Center for International Exchange, 1995, pp. 367-390.

- Bloor, K., Understanding Global Politics, Bristol, England. https://www.e-ir.info/publication/understanding-global-politics/, accessed Oct. 14, 2022.: E-International Relations, 2022.

- Nabafu, R., Moya, M. B., Isoh, A. V., Kituyi, G. M., Ngwa, O., “Towards use of capability, opportunity and motivation model in predicting Ugandan citizens’ behavior towards engagement in policy formulation through e-participation,” The African Review, vol. 1(aop), no. https://brill.com/view/journals/tare/50/1/article-p111_7.xml?language=en, pp. 1-25, 2013.

- El Taraboulsi, S., Krebs, H.B., Zyck, S.A., Willets-King, B., “Regional Organisations and Humanitarian Action: Rethinking Regional Engagement,” Overseas Development Group, London. http://cdn-odi-production.s3-website-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/media/documents/10579.pdf, 2016.

- Kelly, R., Regional integration: choosing plutocracy, New York: Palgrave Macmillan., 2010.

- Booth, D., “Development as a collective action problem: Addressing the real challenges of African governance,” Africa Power and Politics Programme (APPP), London. https://cdn.odi.org/media/documents/appp-synthesis-report-development-as-a-collective-action-problem-david-booth-o_7un7DOu.pdf. Aceesed September 2022, 2012.

- De Lombaerde, P., “Monitoring Regional Integration in the Caribbean and the Role of the EU,” in In Isa-Contreras, Pável (ed.) Anuario de la Integración Regional en el Gran Caribe 2004-2005, Buenos Aires & Caracas, Argentina, CIECA – CIEI – CRIES, 2005, pp. 77-88.

- De Lombaerde, P. Söderbaum, F., van Langenhove, L., Baert, F., “The problem of comparison in comparative regionalism,” Review of International Studies, vol. 36, no. 3. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40783293, p. 731–753, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Volgy, T.J., Fausett, E., Grant, K., Rodgers, S. , “Ergo FIGO: Identifying Formal Intergovernmental Organisations,,” Working Papers Series in International Politics: Department of Political Science, University of Arizona (October), pp. http://www.u.arizona.edu/~volgy/ErgoFigo32907.pdf,accessed October 14, 2022, 2006.

- Aguilera-Lizarraga, M., Interaction dynamics and autonomy in cognitive systems, Zaragoza, Spain. https://zaguan.unizar.es/record/47407/files/TESIS-2016-015.pdf: Doctoral dissertation, University of Zaragoza, 2015.

- Firth, R., “Some Principles of Social Organisation,” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, vol. 85, no. 1/2, p. 1–18. 1955. [CrossRef]

- Crowe,S., Cresswell, K., Robertson, A., Huby, G., Avery, A., Sheikh, A., “The case study approach.,” BMC Med Res Methodol , vol. 11, no. 100. https://bmcmedresmethodol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2288-11-100, 2011. [CrossRef]

- EU-Aims&Values, “Aims and values. https://european-union.europa.eu/principles-countries-history/principles-and-values/aims-and-values_en,” Aims and values, Brussels, https://european-union.europa.eu/principles-countries-history/principles-and-values/aims-and-values_en, 2023.

- ASEAN-Mission, “ASEAN Community Vision 2025: Integrating Countries, Integrating Development,” https://asean.org/, 2020.

- ASEAN-Identity, “ASEAN: A Sharedx Identity,” Becoming ASEAN, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 1-56. https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/The-ASEAN-Magazine-Issue-1-May-2020.pdf. Accessed May 2022, 2020.

- deLombaerde, P., Söderbaum, F., Van Langenhove, L., Baert, F., “The problem of comparison in comparative regionalism,” Review of International Studies, vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 731-753. 2010. [CrossRef]

- EuropeanUnionAims, “Aims and values,” European Uninion, Brussels. https://european-union.europa.eu/principles-countries-history/principles-and-values/aims-and-values_en, (n.d.).

- ASEAN-Aims, “What We Do,” ASEAN. https://asean.org/what-we-do/, 2020.

- Laruelle, M., Peyrouse, S., Uca, I., “Regional Organisations in Central Asia: Patterns of Interaction, Dilemmas of Efficiency,” Working Paper no. 10 of the Institute of Public Policy and Administration. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/315783076, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Alter, K.J., Meunier, S., “The Politics of International Regime Complexity,” Perspectives on Politics, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 13-24. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40407209, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Kawai, M., Wignaraja, G., “The Asian “Noodle Bowl”: Is It Serious for Business?,” Asian Development Bank Institute, no. Working paper, pp. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/155991/adbi-wp136.pdf, 2009. [CrossRef]

- J. Kang, “The Noodle Bowl Effect: Stumbling or Building Block?,” Asian Development Bank, p. http://hdl.handle.net/11540/5114, 2015.

- World-Bank, “Regional Integration,” The World Bank, https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/regional-integration/overview, 2023.

- Linn, J.,F., Pidufala, O. , “Lessons for Central Asia. Experience with Regional Economic Cooperation, Manila,” Asian Development Bank, 2009.

- van Zomeren, M., “Synthesizing individualistic and collectivistic perspectives on environmental and collective action through a relational perspective,” Theory & Psychology, vol. 24, no. 6, pp. 775-794. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&d, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Tönnies, F., “Fünfzehn Thesen zur Erneurung des “Familienlebens”,” in In C.P. Loomis (Ed.), Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft (1st ed), vol. 1, Mineola, NY., Courier Corporation, 1983, pp. 35-132.

- Bell, M.M., “The Dialogue Of Solidarities, Or Why The Lion Spared Androcles,” Sociological Focus, vol. 31, no. 2, p. 181–199. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20831986, 1998. [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G., Culture's consequences, Beverly Hills, CA, USA: Sage., 1980.

- Triandis, H.C., “Review of Culture's Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values,” Human Organisation, vol. 41`1, pp. 86-90. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44125611, 1982. [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H.C., Individualism and collectivism, Boulder, USA: Westview, 1995.

- Health-Foundation, “Research Scan: Complex adaptive systems,” The Health Foundation, https://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/ComplexAdaptiveSystems.pdf, 2010.

- Yolles, M., “Metacybernetics: Towards a General Theory of Higher Order Cybernetics,” Systems, vol. 9, no. 2, p. 34. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Yolles, M., Fink, G., A Configuration Approach to Mindset Agency Theory: A Formative Trait Psychology with Affect, Cognition and Behaviour, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

- Yolles, M.I., Fink, G., “Agencies, Normative Personalities, and the Viable Systems Model,” l, Journal Organisational Transformation and Social Change, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 83-116, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A., “Toward a psychology of human agency,” Perspectives on Psychological Science, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 164-180. 2006. [CrossRef]

- Koh, T., “ASEAN and the EU: Differences and challenges,” The Straits Times, August 22, https://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/ASEAN-and-the-eu-differences-and-challenges, accessed August 2020. 2017.

- Bremmer, I., Kupchan, C., “Risk 1: Rogue Russia Top Risks,” Report of the Eurasia Group, January 3, https://www.eurasiagroup.net/live-post/top-risks-2023-1-Rogue-Russia, 2023.

- Dobbins, J., Shatz, H.J., Wyne, A., “Russia Is a Rogue, Not a Peer; China Is a Peer, Not a Rogue: Different Challenges, Different Responses,” RAND Corporation, October, https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PE310.html., Santa Monica, CA, 2019.

- Kelly, G., “.The European Union and its institutions as ‘identity builders’,” in In E. O. Eriksen (Ed.), The unfinished democratization of Europe, Oxford., Oxford University Press, 2010, pp. 157-178.

- Historymole, “Timeline of European Union history,” http://www.historymole.com/cgi-bin/main/results.pl?type=theme&theme=European_Union, 2007.

- Barbier, C., “Tomorrow Europe: The constitution and its ratification,” Centre d’Information sur la Grande Europe. http://www.ciginfo.net/demain/files/tomorrow21en.pdf, 2004.

- De Witte, B., “Variable geometry and differentiation as structural features of the EU legal orderIn Between Flexibility and Disintegration (pp. 9-27). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://www.elgaronline.com/downloadpdf/edcoll/9781783475889/9781783475,” 2017.

- Pettinger, T., “Disadvantages of EU Membership,” Economic Help, July 28, https://www.economicshelp.org/europe/disadvantages-eu/, 2019.

- Tupy, M.L., “The European Union: A Critical Assessment,,” Economic Development Bulletin No. 26, CATO Institute, June 22, https://www.cato.org/economic-development-bulletin/european-union-critical-assessment, 2016.

- Missiroli, A., Cameron, F., Noël, E., “European variable geometry: Past, present and future,” European Policy Centre, Brussels. https://www.iss.europa.eu/sites/default/files/EUISSFiles/cp038e.pdf. Retrieved January 15, 2022, 1999.

- C. Brandier, “Tomorrow Europe: The constitution and its ratification.,” Centre d’Information sur la Grande Europe, Brussels. https://www.iss.europa.eu/sites/default/files/EUISSFiles/cp038e.pdf. Retrieved January 15, 2022, 2004.

- Moody, J., White, D., “Structural Cohesion and Embeddedness: A Hierarchical Concept of Social Groups,” American Sociological Review, vol. 68, pp. 103-127. 2003. [CrossRef]

- EU-Business, “EU treaty reform: Two-speed Europe looms.,” https://www.eubusiness.com/news-eu/1192715629.36, 2007.

- Thorp, T., “Hungary opposes two-speed Europe,” https://www.templetonthorp.com/en/news120, 2004.

- Carter, P., Managing offenders, reducing crime: A new approach, London: Strategy Unit, 2003.

- Yolles, M., “Understanding the Dynamics of European Politics,” European Intergation Online Papers, vol. 13, no. 27, pp. 1-28. (citing Fray, 2003), 2009. [CrossRef]

- Gillingham, J., European integration, 1950–2003: Superstate or new market economy?, Cambridge, https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/european-integration-19502003/1CEBFEDAD1DD8A0F37F222462E8F4ED3: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Fray, P., “Two-speed Europe push as constitution talks collapse,” Herald Correspondent in London, p. http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2003/12/14/1071336813329.html?from=storyrhs&oneclick=true, 12 December 2004.

- Albert, M.,, Capitalisme contre Capitalisme, Paris: Le Seuil, 1991.

- Spisak, A., Tsoukalis, C., “Three Years On, Brexit Casts a Long Shadow Over the UK Economy,” Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, February 3, https://www.institute.global/insights/geopolitics-and-security/three-years-brexit-casts-long-shadow-over-, 2023.

- ASEAN-Origins, “The Founding of ASEAN,” ASEAN, https://asean.org/the-founding-of-asean/, 2020.

- Mahbubani, K, Tang, K., “ASEAN: An Unexpected Success Story,” The Cairo Teview, Spring, https://www.thecairoreview.com/essays/asean-an-unexpected-success-story/ 2018.

- Zhang, R., “Beating the Odds: How ASEAN Helped Southeast Asia Succeed,” Harvard Political Review, pp. https://harvardpolitics.com/asean-beats-the-odds/, 15 March 2021.

- ASEAN-Sec, “ASEAN Investment,” Report 2020–2021: Investing in Industry 4.0, ASEAN Secretariate. https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/AIR-2020-2021.pdf, 2021.

- Mahbubani, K., Tang, K., “ASEAN: An Unexpected Success Story,,” The Cairo Review of International Affairs, pp. https://www.thecairoreview.com/essays/ASEAN-an-unexpected-success-story/, accessed August 2021, Spring 2018.

- Dosch, J., “Examining ASEAN’s effectiveness in managing South China Sea disputes,” The Pacific Review, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 119-147. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Druce, S.D., Baikoen. E.,Y., “Circumventing Conflict: The Indonesia–Malaysia Ambalat Block Dispute,” in in Oish, M. (ed.), Contemporary Conflicts in Southeast Asia,Asia in Transition 3, Singapore, Springer Science+Business Media, 2016, pp. 3. [CrossRef]

- Fisher, D., “The ‘Regional and National Context’ Under the ASEAN Human Rights Declaration and Its Implications for Minority RightsFaculty of Law,” Stockholm University Research Paper No. 50, p. https://ssrn.com/abstract=307643, 2017.

- Chachavalpongpun, P., “Is Promoting Human Rights in ASEAN an Impossible Task? Developments in the region suggest that the goal remains far from becoming a reality anytime soon,” The Diplomat, Japan, pp. https://thediplomat.com/2018/01/is-promoting-human-rights-in-asean-an-impossible-task/, 8 January 2018.

- Kurlantzick, J., “ASEAN’s Future and Asian Integration,” Working Paper from the Council on Foreign Relations, New York, 2012.

- Kurlantzick, J., “Southeast Asia: Democracy Under Siege,” The Diplomat, pp. https://thediplomat.com/2014/11/southeast-asia-democracy-under-siege/, 20 November 2014.

- Webber, D., “Two funerals and a wedding? The ups and downs of regionalism in East Asia and Asia-Pacific after the Asian crisis,” The Pacific Review, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 339-372. 2001. [CrossRef]

- Hutt, D., “Europe-ASEAN relations: What to expect in 2023,” The Diplomat, Japan, pp. https://www.dw.com/en/europe-asean-relations-what-to-expect-in-2023/a-64196399, 19 January 2023.

- FL., “ASEAN Nations’ Scores as per the Hofstede Model: Scores of six ASEAN nations are evaluated as per the Hofstede model,” https://www.futurelearn.com/info/courses/multiculturalism-in-asean/0/steps/217697, 2023.

- Hofstede, G., Neuijen, B.D., Ohayv, D., Sanders, G., “Measuring organisational cultures: A qualitative and quantitative study across twenty cases,” Administrative Science Quarterly, vol. 35, pp. 286–316. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Peter-Kindle/post/Can-anyone-provide-Hofstedes-organisational-culture-measurement-survey-instrument/attachment/59d64bc879197b80779a5be4/AS%3A481735231184897%401491866037824/download/Hofstede+et+al+%281990%29.p, 1990. [CrossRef]

- McSweeney, B., “Dynamic Diversity: Variety and Variation Within Countries,” , Organisation Studies, vol. 30, no. 9, pp. 933–957. https://www.academia.edu/download/36684099/McSweeney_OS_2009-1.pdf, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Jreisat, J.E., Comparative Public Administration and Policy, Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2002.

- Nuland, V., “ASEAN Declaration and Human Rights,” U.S. Department of State, Press Statement Victoria Nuland, Department Spokesperson, Office of the Spokesperson Washington, DC, pp. https://2009-2017.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2012/11/200987.htm, 20 November 2012.

- ICJ, “Asia,” International Commissions of Jurists, http://www.ijrcenter.org/regional/asia/, 2012.

- Kurlantzick, J., “ASEAN Meets, But Remains Mostly Silent on Major Regional Issues,” Council on Foreign Relations, New York. https://www.cfr.org/blog/ASEAN-meets-remains-mostly-silent-major-regional-issues, 2018.

- ASEAN-Bali-Concord, “Bali Declaration on ASEAN Community in a Global Community of Nations “Bali Concord III”,” https://cil.nus.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/2011-Bali-Concord-III.pdf, 2011.

- Jones, W.J., “Universalizing human rights the ASEAN way,” International Journal of Social Sciences, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 1-15. https://www.academia.edu/35065363/Universalizing_Human_Rights_The_ASEAN_Way, 2014.

- ASEAN-Development-Bank, “ASEAN Economic Intergration Report,” ASEAN Development Bank. https://www.adb.org/publications/series/asian-economic-integration-report (pp. 16-17, 22-23), 2011 and 2014.

- Eurostat., “Intra-EU trade in goods - main features,” European Union. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?oldid=452727, Brussels, 2015.

- Lin, H.C., “ASEAN Charter: Deeper Regional Integration under International Law?,” Chinese Journal of International Law, vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 821-837. First published online: November 29, 2010 http://chinesejil.oxfordjournals.org/, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.M., Smith, M.L.R., “Making process, not progress: ASEAN and the evolving East Asian regional order,” International Security, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 148-184. 2007. [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.L., “ASEAN's Ninth Summit: Solidifying Regional Cohesion, Advancing External Linkages,” Contemporary Southeast Asia, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 416-433. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25798702, 2004.

- Murray, P., “Comparative regional integration in the EU and East Asia: Moving beyond integration snobbery,” International Politics, vol. 47, no. 3, pp. 308-323. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Philomena-Mur-ray/publication/228420298, 2010. [CrossRef]

- L. Jones, “Still in the “Drivers’ Seat”, But for How Long? ASEAN’s Capacity for Leadership in East-Asian International Relations,” Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 95-113. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., “The ASEAN Regional Forum and Preventive Diplomacy: Built to Fail?,” Asian Security, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 44-60. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Arase, D., “Non-Traditional Security in China-ASEAN Cooperation: The Institutionalization of Regional Security Cooperation and the Evolution of East Asian Regionalism,” Asian Survey, vol. 50, no. 4, p. 808–833. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Raha, A., “A fighting chance: ASEAN’s year ahead,” BNP Paribas, https://cib.bnpparibas.com/think/a-fighting-chance-ASEAN-s-year-ahead_a-1-3875.html, 2020.

- Koga, K., “Personal communication,” 2023.

- R. Severino, “ASEAN: Building the Peace in Southeast Asia,” Association of South East Nations, https://ASEAN.org/?static_post=ASEAN-building-the-peace-in-southeast-asia-2, accessed August 2021., 2001.

- G. B.K., “Problems of Regional Cooperation in Southeast Asia,” World Politics, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 222-253. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2009506, 1964. [CrossRef]

- A. Vejjavava, “Policy of Non-interference must give way to better systems of representation,” Bangkok Post, pp. http://www.bangkokpost.com/opinion/opinion/1731815/for-a-prosperous-future-we-must-rethink-the-ASEAN-way, 17 August 2019.

- Lara, R.L., “The Problem of Sovereignty, International Law, and Intellectual Conscience,” Journal of Philosophy of International Law, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 1-26. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2615135, 2014.

- Lauterpacht, E., “Sovereignty-Myth or Reality? International Affairs,” International Affairs, vol. 73, no. 1, pp. 137-150. 1997. [CrossRef]

- Sukma, R., “ASEAN beyond 2015: The imperatives for further institutional changes,” ERIA Discussion Paper, pp. Series 1. https://www.eria.org/ERIA-DP-2014-01.pdf, accessed Dec. 17, 2022., 2014.

- Schiemann, K., “Europe and the Loss of Sovereignty,” The International and Comparative Law Quarterly, vol. 56, no. 3, pp. 475-489. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/248629059_Europe_and_the_Loss_of_Sovereignty1, 2007. [CrossRef]

- L. Aggestam, “The European Union at the Crossroads,” in In Landau, A., Whitman, R.G. (eds) Rethinking the European Union, London, Palgrave Macmillan, 1997, pp. 69-86. [CrossRef]

- Leonard, M., Shapiro, J., “EMPOWERING EU MEMBER STATES WITH STRATEGIC SOVEREIGNTY.,” European Council on Foreign Relations. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep21489, 2019.

- Pavel, S., Supinit, V., “Bangladesh Invented Bioplastic Jute Poly Bag and International Market Potentials,” Open Journal of Business and Management, vol. 5, pp. 624-640. https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0CAIQw7AJahcKEwjA9unF9YX_AhUAAAAAHQAAAAAQCg&url=https%3A%2F%2Fpapers.ssrn.com%2Fsol3%2Fpapers.cfm%3Fabstract_id%3D3396267&psig=AOvVaw1, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Angresano, J., “ASEAN + 3 is an economic community their future,” in In M. G. Plummer & A. Jones (Eds.), International economic integration and Asia, Singapore, World Scientific, 2006, pp. 50-88. [CrossRef]

- Yolles, M.I., Iles, P., “Two-speed Europe and international joint alliance theory,” in in Owsiński, J.W., (ed), Modelling Economies and Societies in Transition: Integration, Trade, Innovation & Finance: From Continental to Local Perspectives, 2004, pp. 229-246. URL: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Maurice-Yolles/publication/352539806_A_Metahistorical_Information_Theory_of_Social_Change_the_theory/links/60ce0fdf458515dc1795050b/A-Metahistorical-Information-Theory-of-Social-Change-the-theory.pdf.

- Yolles, M.I., Organisation as complex systems: An introduction to knowledge cybernetics, Greenwich, England. https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0CAIQw7AJahcKEwjg6uf2-YX_AhUAAAAAHQAAAAAQAw&url=https%3A%2F%2Furanos.ch%2Fresearch%2Freferences%2FYolles_2006%2FMtC_V2.pdf&psig=AOvVaw0yJytM64vYZZVP3MkKB: Information Age Publishing, 2006.

- Timms, A., “Malaysia’s Zeti Is a Liberal Voice at a Time of Political Uncertainty,” Institutional Investor. https://www.institutionalinvestor.com/article/b14zbd1dbymht2/malaysias-zeti-is-a-liberal-voice-at-a-time-of-political-uncertainty, 2013.

- T. Rautakivi, “The Role and Effects of Efficacy in Socio-Economic Development and Foreign Direct Investment: A Comparative Study of South Korea and Singapore,” Doctoral Thesis, Institute of International Studies, Ramkamhaeng University, Bangkok, 2012.

- De Meur, G., Berg-Schlosser, D., “Comparing political systems: Establishing similarities and Dissimilarities,” European Journal of Political Research, vol. 26, pp. 193-219. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Dirk-Berg-Schlosser/publication/255664224_Comparing_political_systems_Establishing_similarities_and_dissimilarities/links/607d4c7f8ea909241e0cef1b, 1994. [CrossRef]

- Lim, L., “On the applicability of the most similar systems design and the most different systems design in comparative research,” International Journal of Social Research Methodology, vol. 11, no. 5, pp. 389-401. 2006. [CrossRef]

- Mattli, W., The logic of regional integration: Europe and beyond, Cambridge, . URL: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/logic-of-regional-integration/1001F7BE284C55D67F3B3F34E7D6F1F1: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- Bradley, B., “Post-war European Integration: How We Got Here. E-International Relations,” E-Internaltional Relations. https://www.e-ir.info/2012/02/15/post-war-european-integration-how-we-got-here/, 2012.

- Lambrechts, K., Alden, C., “Regionalism and Regionalisation,” in In Haynes, J. (eds). Palgrave Advances in Development Studies, London, Palgrave Macmillan, 2005, pp. 288-321. [CrossRef]

- Hoshiro, H., “Does regionalization promote regionalism? Evidence from East Asia,” Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 99-219. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/24761028.2019.1693944, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Pimoljinda, T., Thianthong A., “Human Trafficking in Burma and the Solutions Which Have Never Reached,” Journal of Asia Pacific Studies, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 524-544, 2010.

- Breslin, N.S., Higgott, R., “Studying Regions: Learning from the Old, Constructing the New,” New Political Economy, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 333-352, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Hurrell, A., “Explaining the resurgence of regionalism in world politics,” Review of International Studies, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 331-358. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20097421, 1995. [CrossRef]

- Breslin, S., Higgott, R., “Studying regions: Learning from the old, constructing the new,” New Political Economy, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 333-352. 2000. [CrossRef]

- Hermann, C., “Neoliberalism in the European Union,” Studies in Political Economy, vol. 79, no. 1, pp. 61-90. 2007. [CrossRef]

- Sliwinski, A., “The European Union and the neoliberal paradigm: A critical analysis of the EU’s economic governance framework,” Journal of Contemporary European Studies, vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 443-458. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Geyer, R., Exploring European social policy, Bistol: Polity Press, 2000.

- Kay, J.A., Thompson, D.J., “Privatisation: A Policy in Search of a Rationale,” The Economic Journal, vol. 96, no. 381, pp. 18-32. 1986. [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D., A brief history of neoliberalism, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press., 2005.

- Sliwinski, K., The European Union and the neoliberal agenda, Abingdon-on-Thames, UK.: Routledge, 2018.

- Gilpin, R., The political economy of international relations, Princeton, USA: Princeton University Press., 1987.

- Ekelund Jr, R.B., Tollison, R.D., Mercantilism as a rent-seeking society: Economic regulation in historical perspective, Texas: Texas A & M University Press, 1981.

- Jackson, R. H., Sørensen, G., Introduction to international relations: Theories and approaches, Oxford: Oxford University Press., 1998.

- Baldwin, R., Wyplosz, C., The economics of European integration (5th ed.), New York: McGraw-Hill Education, 2015.

- Kawai, M., Wignaraja, G., “Asian FTAs: Trends, Prospects, and Challenges. ADB Economics,” Working Paper Series No. 226. Asian Development Bank, 2009.

- ASEAN-Delelopmental-Progress, “ASEAN economic community 2015: Progress and key achievements,” https://www.asean.org/storage/images/2015/November/aec-page/AEC-2015-Progress-and-Key-Achievements.pdf, 2012.

- ASEAN-Secretariat2014, “ASEAN trade in goods agreement (ATIGA),” https://www.asean.org/storage/images/2015/February/ATIGA/ATIGA%202014.pdf, 2014.

- ASEAN-Secretariat, “ASEAN investment report 2019: FDI in services: Focus on health care.,” ASEAN Secretariat. https://unctad.org/publication/asean-investment-report-2019, Jakarta, 2019.

- Asplund, J., “Aubert And Soft Data,” Sociological Research, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 96-104. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20851308, translated by https://translate.google.com/?sl=auto&tl=en&op=docs, 1966.

- Asplund, J., Essä om Gemeinschaft och Gesellschaft, Göteborg: Bokförlaget, Korpen, 1991.

- Cooley, C.,H., Social Organisation: A Study of the Larger Mind, New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons., 1909.

- Vaisey, S., “Structure, Culture, and Community: The Search for Belonging in 50 Urban Communes.,” American Sociological Review, vol. 72, no. 6, p. 851–73., 2007. [CrossRef]

- Beckwith, C., “Who Belongs? How Status Influences the Experience of Gemeinschaft,” Social Psychology Quarterly, vol. 82, no. 1, p. 31–50. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Brewer, M.B., Gardner, W., “Who Is This ‘We’? Levels of Collective Identity and Self Representations,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 7, p. 83–93, 1996. [CrossRef]

- Molm,L.D., Collett,J.L., Schaefer, D.L., “Building Solidarity through Generalized Exchange: A Theory of Reciprocity,” American Journal of Sociology, vol. 113, no. 1, p. 205–42., 2007. [CrossRef]

- Willer, R., “Groups Reward Individual Sacrifice: The Status Solution to the Collective Action Problem,” American Sociological Review, vol. 74, no. 1, p. 23–43., 2009. [CrossRef]

- Wolvén, L.,E., Vinberg, S., “Gemeinschaft, Gesellschaft and Leadership in Non-Profit Organisations - A Comparative Study between Non-Profit Organisations and Organisations within the Public and Private Sector in the Northern Part of Sweden,” in EGPA 2004 Annual Conference, Ljubljana. https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0CAIQw7AJahcKEwjArf6Cuob_AhUAAAAAHQAAAAAQCQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fstudieplan.miun.se%2Fconveris%2Fportal%2Fdetail%2FPublication%2F377780%3Fauxfun%3D%26lang%3Dsv_SE&ps, 2004.

- Rodriguez, E., “Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft,” in Encyclopedia Britannica, 2016, pp. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Gemeinschaft-and-Gesellschaft.

- Triandis, H.C., Bontempo, R., Villareal, M.J., “Individualism and Collectivism: Cross-Cultural Perspectives on Self-Ingroup Relationships,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 54, no. 2, pp. 323-338, 1988. [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H.C., “Collectivism and individualism: A reconceptualization of a basic concept in cross-cultural social psychology,” in In G. K. Verma, C. Bagley (Eds.), Personality, attitudes, on motivation., Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press, 1989, pp. 41-133.

- Hofstede, G., Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations, Los Angeles and London: Sage Publications, 2001.

- Schwartz, S.H., “Beyond individualism/collectivism: New dimensions of values,” in In U. Kim, H.C. Triandis, C. Kagitcibasi, S.C. Choi and G. Yoon, (eds.), Individualism and Collectivism: Theory Application and Methods, Newbury Park, CA, Sage, 1994, pp. 85-119.

- Minkov, M., What makes us different and similar: a new interpretation of the World Values Survey and other cross-cultural data, Sofia, Bulgaria: Klasika I stil Publishing House, 2007.

- Hofstede, G.J., Jonker, C.M., Verwaart, T., “Individualism and Collectivism in Trade Agents,” IEA/AIE '08: Proceedings of the 21st international conference on Industrial, Engineering and Other Applications of Applied Intelligent Systems, pp. 492-501. https://ii.tudelft.nl/~catholijn/publications/sites/default/files/CultureIND2008.pdf, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, P.M., “Linking Social Change and Developmental Change: Shifting Pathways of Human Development,” , Developmental Psychology, vol. 45, no. 2, pp. 401–418. https://greenfieldlab.psych.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/168/2019/01/47-Greenfield-Theory-of-Social-Change-and-Human-Development-2009.pdf, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Davis, J., Marciano. A., Runde, J., The Elgar Companion to Economics and Philosophy, Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited., 2004.

- Herrmann-Pillath, C., “Social Capital, Chinese Style: Individualism, Relational Collectivism and the Cultural Embeddedness of the Institutions-Performance Link,” Working Paper Series no 132, Frankfurt School of finance and Management, Frankfurt, 2009.

- Schwartz, S.H., “Individualism-collectivism: Critique and proposed refinements,” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 139-157. 1990. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S. H., Bilsky, W., “Toward a universal psychological structure of human values,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 53, no. 3, pp. 550–562. 1987. [CrossRef]

- Yolles, M.I., Fink, G., “An Introduction to Mindset Theory,” Working Paper of the Organisational Coherence and Trajectory (OCT), p. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2272169, 2013.

- M. Maruyama, “Mindscapes and science theories,” Current Anthropology, vol. 21, pp. 589-599. https://pensamientocomplejo.org/?mdocs-file=351, 1980. [CrossRef]

- Neff, C.D., “Reasoning About Rights and Duties in the Context of Indian Family Life,” Doctoral Thesis, Dept. Education, University of California, Berkeley, USA. https://www.proquest.com/openview/ca713fdd8d0d245e90b07480b0879845/1?pq-origsite=gscholar, 1997.

- Greenfield, C., “Can run, play on bikes, jump the zoom slide, and play on the swings: Exploring the value of outdoor play,” Australian Journal of Early Childhood, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 1-5. 2004. [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, P., Social and Cultural Dynamics, in 4 volumes, New York: Bedminster Press. Originally published in 1937-1942 by the Amer, Book, Co, N,Y,, 1962.

- Browning, M.A., “Self-Sacrifice vs. Collectivism: Examining Construct Overlap with Asian-Americans,” PhD dissertation for the Faculty of the California School of Professional Psychology, Alliant International University Fresno, Fresno. Alliant International University ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2017. 10284531. https://www.proquest.com/openview/c4e5d256796a4c59d6bdb3c5584d9814/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750, 2017.

- Kim, I., Jung,, H..J., Lee, Y., “Consumers’ Value and Risk Perceptions of Circular Fashion: Comparison between Second hand, Upcycled, and Recycled Clothing,” Sustainability, vol. 13, p. 1208. https://intelligentfood.nl/, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Oyserman, D., Coon, H. M., Kemmelmeier, M., “Rethinking individualism and collectivism: evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses,” Psychological bulletin, vol. 128, no. 1, p. 3–72, 2002. [CrossRef]

- Rayner, J., “When Participation Begins with a “NO”: How Some Costa Ricans Realized Direct Democracy by Contesting Free Trade,” Etnofoor, vol. 26, no. 2, p. 11–32. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43264057, 2014.

- Craigie, A., “Regional and national identity mobilization in Canada and Britain: Nova Scotia and North East England compared.,” Doctoral dissertation, School of Social and Political Studies, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh. https://era.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/4482, 2010.

- Garrafa, V., “Solidarity and Cooperation,” in Handbook of Global Bioethics, Los Angelese and London, Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht Volume 1, Section II Principles of Global Bioethics,, 2014, pp. 169-186. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/278692471_Handbook_of_Global_Bioethics. [CrossRef]

- Sagiv, L., Schwartz, S.H., “Cultural values in organisations: insights for Europe,” EuropeanJ. International Management, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 176-190. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/234021865_Cultural_Values_in_Organisations_Insights_for_Europe, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Shelly, R.K., Bassin, E., “Cohesion, Solidarity, and Interaction,” Sociological Focus, vol. 22, no. 2, p. 143–50. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20831507. Accessed 13 Mar. 2023., 1989.

- Webber, C., “Revaluating relative deprivation theory,” Theoretical Criminolog, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 201-221. 2003. [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.L., “Weak states’ regionalism: ASEAN and the limits of security cooperation in Pacific Asia,” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific,, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 209-240, 2004.

- Jones, D.,M. , Jenne, N., “Weak states' regionalism : ASEAN and the limits of security cooperation in Pacific Asia,” International relations of the Asia-Pacific, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 209-240, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Thayer, C., “Flight MH370 Shows Limits of ASEAN’s Maritime Cooperation,” The Diplomat, pp. https://thediplomat.com/2014/03/flight-mh370-shows-limits-of-aseans-maritime-cooperation/, 18 March 18 2014.

- Scharfbillig, M., Smillie, L., Mair, D., Sienkiewicz, M., Keimer, J., Pinho Dos Santos, R., Vinagreiro Alves, H., Vecchione, E., & Scheunemann L., “Values and Identities - a policymaker’s guide: Executive Summary.,” Publications Office of the European. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Manners, I., “Normative Power Europe: A contradiction in Terms?,” Journal of Common Market Studies, vol. 40, no. 2, pp. 235-258. 2002. [CrossRef]

- Anastasakis, O., “The Europeanization of the Balkans,” Brown Journal of World Affairs, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 77-89. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24590667, 2005.

- M. Vatikiotis, “ASEAN 10: The Political and Cultural Dimensions of Southeast Asian Unity,” Southeast Asian Journal of Social Science, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 77-88. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24590667, 1999. [CrossRef]

- Forst, R., “Toleration, justice and reasoning,” in in C. McKinnon and D. Castiglione (eds.), The culture of toleration in diverse socities, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2003, pp. 71-85. https://www.culturalpolicies.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Fors.

- Achmad, S., “Digital Literacy As a Foundation for Religious Moderation Learning at Salatiga's Al-Hijrah Tingkir Islamic Boarding School,” Paedagogia: Jurnal Pendidikan, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 119-129. https://www.academia.edu/download/91016044/208-Article_Text-695-1, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Craiutu, A., Faces of Moderation: The Art of Balance in an Age of Extremes, Victoria, BC and Munich, Germany: AbeBooks, 2016.

- Goh, G.H.L., “The ‘ASEAN way’: Non-intervention and ASEAN’s role in conflict management,” Stanford Journal of East Asian Affairs, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 113-118. https://www.academia.edu/download/31542602/geasia1.pdf, 2000.

- Roberts, C., “State weakness and political values: ramifications for the ASEAN community,” in in R. Emmers, (eds), ASEAN and the Institutionalisation of East Asia, London, Routledge., 2012, p. 11–26.

- Almuttaqi, I., “ASEAN unity in doubt as Indonesia calls for special COVID-19 summit,” The Jakarta Post, pp. https://www.thejakartapost.com/seasia/2020/04/02/asean-unity-in-doubt-as-indonesia-calls-for-special-covid-19-summit.html, 2 April 2020.

- Nandyatama, R., “ASEAN unity in doubt as Indonesia calls for special COVID-19 summit,” The Jakarta Post, pp. https://www.thejakartapost.com/seasia/2020/04/02/asean-unity-in-doubt-as-indonesia-calls-for-special-covid-19-summit.html, 2 February 2020.

- Giles, H., Giles, J., “Ingroups and Outgroups,” in In Giles H., Reid S. A., Harwood J. (Eds.). The dynamics of intergroup communication, New York, Peter Lang, 2010. https://www.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/upm-. [CrossRef]

- Thion, S., “What is the Meaning of Community?,” Cambodia Development Review, vol. 3, no. 3, p. 12–13, 1999.

- Oveson, J., Trankell, I. B., Öjendal, J., “When every household is an island: Social organization and power structures in rural Cambodia,” Uppsala Research Reports in Cultural Anthropology, vol. 15, pp. 1-28, 1996.

- Chou, C., “The Local Governance of Common Pool Resources: The Case of Irrigation Water in Cambodia,” Working Paper Series No. 47, Cambodian Development Resource Institute, Phnom Penh, 2010.

- Öjendal, J., “Sharing the Good – Modes of Managing Water Resources in the Lower Mekong River Basin,” Doctoral thesis at Dept. Peace and Development Research, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, 2000.

- Seah, S., Lin. J., Martinus, M., Suvannaphakdy, S., Thao, P.T.P., “The State of Southeast Asia: 2023 Survey Report,” ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore. https://www.iseas.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/The-State-of-SEA-2023-Final-Digital-V4-09-Feb-2023.pdf, 2023.

- Rautakivi, T., Siriprasertchok, R., Melin, H., A Critical Evaluation of Individualism, Collectivism and Collective Action, Tampere, Finland: Tampere University Press, 2022.

- Yoshimatsu, H., “Collective action problems and regional integration in ASEAN,” CSGR Working Paper, vol. 198, no. 6, p. https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/pais/research/csgr/papers/workingpapers/2006/wp19806.pdf, 2006.

- Yang, L., Cormican, K., “The crossovers and connectivity between systems engineering and the sustainable development goals: a scoping study,” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 6, pp. 3176. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/6/3176, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Dorronsoro, G., Grojean, O., Identity, Conflict and Politics in Turkey, Iran and Pakistan, Oxford: Oxford University Press., 2018.

- Wheatley, R., “African international relations: A metafunctional approach,” Doctoral dissertation, dept. Political Science, Clark Atlanta University, Atlanta, 2011.

- Louis, W. R., Thomas, E. F., McGarty, C., Lizzio-Wilson, M., Amiot, C. E., Moghaddam, F. M., “When social movements fail or succeed: social psychological consequences of a collective action’s outcome,” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 11, p. 1155950. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Yolles, M., Di Fatta, D., “Modelling identity types through agency: part 1 defragmenting identity theory,” Kybernetes, vol. 46, no. 6, pp. 1068-1084. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317057374_Modelling_identity_types_through_agency_part_1_defragmenting_identity_theory, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Di Fatta, D., Yolles, M., “Modelling multiples identity types through agency: Part 3 - mindsets and the Trump election,” Kybernetes, vol. 47, no. 4, pp. 638-655. , 2018. [CrossRef]

- De Lombaerde. P., Pietrangeli, G., “Systems of Indicators for Monitoring Regional Integration Processes: Where Do We Stand?,” The Integrated Assessment Journal, vol. 8, no. 2, p. 39–67. https://iaj.journals.publicknowledgeproject.org/index.php/iaj/article/download, 2008.

- Olofsson, G., “Embeddedness and Integration,” in In Gough, I., Olofsson, G. (eds) Capitalism and Social Cohesion, London, Palgrave Macmillan, 1999, p. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/304701247_Embeddedness_and_Integration_An_Essay_on_Karl_Polanyi%27s_%27The_Great_Transformation%27.

- Yoshimatsu, H., “Collective Action Problems and Regional Integration in ASEAN,” Contemporary Southeast Asia, vol. 28, no. 1, p. 115–140. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25798770, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Koga, K., “The Normative Power of The "ASEAN Way,” Stanford Journal of East Asian Affairs, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 80-95. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325360676_The_Normative_Power_of_the_ASEAN_Way_Potentials_Limitations_and_Implications_for_East_Asian_Regionalism, 2010.

- Koga, K., Managing Great Power Politics: ASEAN, Institutional Strategy, and the South China Sea, London: Palgrave Macmillan., 2022.

- Guo, K., Yolles, M., Fink, G., Iles, P., The changing organization: Agency theory in a cross-cultural context, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

- Foucault, M., The archaeology of knowledge and the discourse on language, New York: Pantheon Books., 1972.

- Easton, D., The political system: An inquiry into the state of political science, New York: Knopf, 1953.

- Almond, G.A., Bingham Powell Jr., A., Comparative Politics: A Developmental Approach, Boston: Little, Brown, 1966.

- Jaturapol, L., “The role of social science research in Thailand: A case study of the Thai Khadi Research Institute. Social Science Asia,” Social Science Asia, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 121-130., 2002.

- Steinbruner, J.D., The cybernetic theory of decision: New dimensions of political analysis, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1974.

- Kim, K.W., “The Limits of Behavioural Explanation in Politics,” The Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science, vol. 31, no. 3, pp. 315-327. https://www.jstor.org/stable/139732, 1965.

- Moulin-Stożek, D., “The social construction of character,” Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, vol. 49, no. 1, pp. 24-39. http://pure-oai.bham.ac.uk/ws/files/55069505/The_social_construction_of_character.pdf, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Young, R.M., “Scientism in the history of management theory,” Science as Culture, vol. 1, no. 8, pp. 118-143. http://ww.psychoanalysis-and-therapy.com/human_nature/papers/shmt.doc, 1990. [CrossRef]

- Dobuzinskis, L., The Self-Organizing Polity: An Epistemological Analysis of Political Life, Boulder, USA: Westview Press, 1987.

- Huntington, S.P., No Easy Choice: Political Participation in Developing Countries, , Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press, 1986.

- Easton, D., A Systems Analysis of Political Life, New York: Wiley, 1965.

- Easton, D., “The new revolution in political science,” American Political Science Review, vol. 63, p. 1051–61, 1969. [CrossRef]

- Easton, D., The Analysis of Political Structure, New York: Routledge, 1990.

- Fink, G., Yolles, M., “Collective emotion regulation in an organisation – a plural agency with cognition and affect,” Journal of Organizational Change Management, vol. 28, no. 5, pp. 832-871. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2681040, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Caspi, A., Roberts, B.W., Shiner, R.L., “Personality development: Stability and changengs%20595/Caspi%2005%20per%20dev%20copy.pdf,” Annual Review of Psychology, vol. 56, p. 453–484. https://academic.udayton.edu/JackBauer/Readi, 2005.

- Yolles, M., “A social psychological basis of corruption and sociopathology,” Journal of Organisational Change Management, vol. 22, no. 6, pp. 691-731. 2009. [CrossRef]

- C. I. S. von Scheve, “Towards a Theory of Collective Emotions,” Emotion Review, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 406-413. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258997923_Towards_a_Theory_of_Collective_Emotions, 2013. [CrossRef]

- G. Sullivan, “Collective emotions,” Social and Personality Psychology Compass, vol. 9, no. 8, pp. 383-393. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Kets de Vries, M.F.R., Organisations on the Couch: Clinical Perspectives on Organisational Behaviour and Change, NY, USA.: Jossey-Bass Inc (a Wiley publication), 1991.

- Sperry, L., “Classification System Proposed for Workplace Behavior,” Academy of Organisational and Occupational Psychiatry, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. http://www.aoop.org/archive-bulletin/1995springcategry.shtml, accessed July 2010., 1995.

- Simon, H., A., “The Architecture of Complexity,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 106, no. 6, pp. 467-482., 2 December 1962.

- Ashkanasy, N.M., “Emotions in organizations: A multilevel perspective,” in In F. Dansereau & F. J. Yammarino (Eds.), Research in multi-level issues: Vol. 2. Multi-level issues in organizational behavior and strategy, Amsteedam, Elsevier, 2003, pp. 9-54.

- Yolles, M., “Agency, Generic Ecosystems and Sustainable Development: Part 1 The Foundation,” Kybernetes, vol. 49, no. 7, pp. 1813-1836, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Beer, S., The Heart of Enterprise, London: Wiley, 1979.

- Schwarz, E., “Towards a Holistic Cybernetics: From Science through Epistemology to Being,” Cybernetics and Human Knowing, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 17-50, 1997.

- Maturana H.R., Varela F.J.,, Autopoiesis and Cognition, Boston:: Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science, 1979.

- Piaget, J.,, The Psychology of Intelligence, New York: Harcourt and Brace (Republished in 1972 by Totowa, NJ: Littlefield Adams), 1950.

- Yolles, M., Fink, G., “Generic Agency Theory, Cybernetic Orders and New Paradigms.,” SSRN Electronic Journal. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2463270., 2014. [CrossRef]

- Cerinšek, G., Dolinsek, S., “Identifying employees’ innovation competency in organisations,” International Journal of Innovation and Learning, vol. 6, no. 2, p. 64–177., 2009. [CrossRef]

- Adeyemo, D.A., “Moderating influence of emotional intelligence on the link between academic self-efficacy and achievement of university students,” Psychology Developing Societies, vol. 19, no. 2, p. 199–213., 2007. [CrossRef]

- Salovey, P., Mayer, J.D., “Emotional intelligence,” Imagination, cognition and personality, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 185-211. https://aec6905spring2013.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/saloveymayer1990emotionalintelligence.pdf, 1990. [CrossRef]

- McComas, S., “Pathological Control: What you should know about Control Freaks! Are they All Narcissist?,” Medium. https://medium.com/@shannon_57963/pathological-control-what-you-should-know-about-control-freaks-are-they-all-narcissist-10f234e15954, 2021.

- Zepinic, V., “Psychopathy in serial killers and political crime,” Psychology, vol. 9, no. 6, pp. 1262-1283, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Yolles, M., “Viable Systems Theory, Anticipation, and Logical Levels of Management,” International Conference on Creativity and Complexity, London School of Economics, 16th - 18th September, . https://emk-complexity.s3.amazonaws.com/events/Conference/MauriceYollesPaper.pdf, 2003.

- Yolles, M., Fink, G., “Agency Mindset Theory,” Acta Europeana Systemica, vol. 3, pp. http://aes.ues-eus.eu/aes2013/enteteAES2013.html, 2013.

- Surel, Y., “The role of cognitive and normative frames in policy-making,” Journal of European Public Policy, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 495-512. 2000. [CrossRef]

- Shotwell, J.M., Wolf, D., Gardner, H., “Styles of Achievement in Early Symbol Use,” in In Brandes, F., (ed), Language, Thought, and Culture, New York, Academic Press, 1980, pp. 175-199. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download;jsessionid=C3F5F32F257CDD193149F674A3670597?doi=10.1.1.726.7490&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

- Park, J.H., “The relationship between social orientation and cultural orientation: A study of Korean American college students,” Journal of Intercultural Communication Research,, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 1-17. 2005. [CrossRef]

- Riley, R., “Organisational Culture: Strong v Weak,” Business Blog, pp. https://www.tutor2u.net/business/blog/organisation-culture-strong-v-weak, 1 October 2014.

- Yolles, M.I., “Revisiting the Political Cybernetics of Organisations,” Kybernetes, vol. 34, no. 5/6, pp. 617-636. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228193718_Revisiting_the_Political_Cybernetics_of_Organisations, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Piaget, J., Inhelder, B., Memory and Intelligence, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul , 1973.

- Cherry, K., “Theories of Intelligence in Psychology,” Very Well Mind, pp. https://www.verywellmind.com/theories-of-intelligence-2795035, 3 November 2022.

- Cherry, K., The Everything Psychology Book, Avon, Mas, USA. https://www.scribd.com/read/336815701/The-Everything-Psychology-Book-Explore-the-human-psyche-and-understand-why-we-do-the-things-we-do: Adams Media, 2010.

- Fink,G., Yolles, M., “Understanding Organisational Intelligences as Constituting Elements of Normative Personality,” SSRN Working paper. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228237685_Understanding_Organisational_Intelligences_as_Constituting_Elements_of_Normative_Personality, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Maturana, H.R., Varela, F.J., The Tree of Knowledge, London.: Shambhala, 1987.

- Bandura, A., Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1986.

- Bandura, A., “A social cognitive theory of personality,” in in Pervin, L. and John, O. (Eds.): Handbook of Personality, 2nd ed, New York, Reprinted in Cervone, D. and Shoda, Y. (Eds.): The Coherence of Personality, Guilford Press, New York., Guilford Publications, 1999, p. 154–196..

- Yolles M., “Consciousness, Sapience and Sentience—A Metacybernetic View,” Systems, vol. 10, no. 6, pp. 254. https://www.mdpi.com/2079-8954/10/6/254, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Lupien, P., “Identity: Personal AND social,” in In P. Lupien (Ed.), The dynamics of identity in online civic activism, Abingdon, UK, Routledge, 2020, pp. 1-14. . [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E., Mael, F., “Social Identity Theory and the Organisation,” The Academy of Management Review, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 20–39. https://www.jstor.org/action/doBasicSearch?Query=Social+Identity+Theory+and+the+Organisation., 1989. [CrossRef]

- Berzonsky, M., “A Social-Cognitive Perspective on Identity Construction,” in , in S.J. Schwartz et al. (eds.), Handbook of Identity Theory and Research, New York, NY, Spinger, 2011, pp. 55-76. [CrossRef]

- Sturkenboom, D., “Understanding Emotional Identities: The Dutch Phlegmatic Temperament as Historical Case-Study,” Low Countries Historical Review, vol. 129, no. 2, pp. 63-191. https://www.academia.edu/download/37688011/Understanding_Emotional_Identities.pdf, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., “Exploration on the Path of Emotional Identification of University Students in New Era on Socialist Core Values,” in In J. Jiao (Ed.), Proceedings of the 2018 2nd International Conference on Education Innovation and Social Science (ICEISS 2018), Jinan, China, Beijing, China, Atlantis Press, 2018, pp. 1-4. [CrossRef]

- Carminati, L., Gao Héliot, Y.F., “Between Multiple Identities and Values: Professionals’ Identity Conflicts in Ethically Charged Situations,” Front. Psychol, vol. 13, p. :813835. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.813835/pdf , 2022. [CrossRef]

- Watson, P.J., Morris, R.J., “Irrational beliefs and the problem of narcissism,” Personality and Individual Differences, vol. 11, no. 11, pp. 1137-1140. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/019188699090025M., 1990. [CrossRef]

- Heracldes, A., “The ending of unending conflicts: separatist wars,” Millennium, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 679-707., 1997. [CrossRef]

- Majeed, R., “What Not to Make of Recalcitrant Emotions,” Erkenn, vol. 87, pp. 747–765. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10670-019-00216-0, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Lederach, J.P., “Editoria,” South Asian Journal of Peacebuilding, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 1-6. http://wiscomp.org/pubn/wiscomp-peace-prints/3-2/editorial.pdf, 2010.

- Matsumoto, D., “Culture, context, and behavior,” Journal of personality, vol. 75, no. 6, pp. 1285-1320. https://davidmatsumoto.com/content/2007%20Matsumoto%20JOP.pdf, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Leong, C. H., Ward, C., “Identity conflict in sojourners,” International journal of intercultural relations, vol. 24, no. 6, pp. 763-776. https://www.academia.edu/download/33907280/sojourners_identity_conflict.pdf, 2000. [CrossRef]

- Priante A, Ehrenhard ML, van den Broek T, Need A., “Identity and collective action via computer-mediated communication: A review and agenda for future research,” New Media Soc, vol. 20, no. 7, pp. 2647-2669. Epub 2017 Dec 7., 2018. [CrossRef]

- Tamis-LeMonda, C.S., Yoshikawa, H., Niwa, K., Niwa, E.Y., “Parents’ Goals for Children: The Dynamic Coexistence of Individualism and Collectivism in Cultures and Individuals,” Social Development, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 183-209. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=88dc162e135bb117d92842b90ec5359e61677220, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Boeree, C.G., “Seven Perspectives,” https://webspace.ship.edu/cgboer/sevenpersp.html, 1998.

- Gromyko, A.A., “Metamorphoses of Political Neoliberalism,” Her Russ Acad Sci, vol. 90, no. 6, pp. 645-652. PMID: 33495679; PMCID: PMC7818069. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7818069/, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Klein, B., “Democracy Optional: China and the Developing World's Challenge to the Washington zconsensus,” UCLA Pacific Basin Law Journal, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 89-149. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5g57c5bb, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Djalante R, Nurhidayah L, Van Minh H, Phuong NTN, Mahendradhata Y, Trias A, Lassa J, Miller, M.A., “COVID-19 and ASEAN responses: Comparative policy analysis,” Prog Disaster Sci, vol. 8, p. 100129. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7577870/, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Safitr, D.M., “From ASEAN to the world: values for a new economy,” July 6, https://francescoeconomy.org/from-asean-to-the-world-values-for-a-new-economy/, 2022.

- Van Doan, J.B.T. , “Harmony and Consensus: Confucius and Habermas on Politics,” May 26, https://vntaiwan.catholic.org.tw/theology/harmony.htm, 1997.

- Brindley, E., “Individualism in Classical Chinese Thought,” Internet encyclopaedia of Philosophy, https://iep.utm.edu/ind-chin/, 2023.

- ASEAN-Sec., “ASEAN Development Outlook: Inclusive and Sustainable Development,,” ASEAN Secretariate, July, https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/ASEAN-Development-Outlook-ADO_FINAL.pdf, 2021.

- De Dios, A.P.T., “The Future of ASEAN,” https://www.academia.edu/68550003/ASEAN_future?from_sitemaps=true&version=2, 2021.

- Zheng, G.X., “Lighting the World with Truth,” Pu Shi Institute for Social Science, p. http://www.pacilution.com/ShowArticle.asp?ArticleID=12719, 23 September 2022.

- Thomas, P., Knight, T., “Happiness, austerity and malignant individualism,” Self & Society, vol. 46, no. 3, pp. 229-244. https://ahpb.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/nl-2019-1-04_Thomas-and-Knight-paper.pdf, 2018.

- Schrepel, K.,L., Kochenov, D.,V., Grabowska-Moroz, B., “EU Values Are Law, after All: Enforcing EU Values through SystemiInfringement Actions by the European Commission and the Member States of the European Union,” Yearbook of European Law, Volume 3, 2020.

- Roberts, C., “The ASEAN Community: Trusting Thy Neighbour? RSIS Commentaries, 110. https://www.rsis.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/CO07110.pdf,” RSIS Commentaries 10, pp. https://www.rsis.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/CO07110.pdf, 2007.

- Hill, E.W., Coufal, K L, “Pragmatic assessment: Analysis of a clinical discourse. Journal of Medical Speech-Language,” Pathology, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 35-44. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4093796/, 2005.

- OECD-2023, “Development Criteria,” OECD papers. https://www.oecd.org/dac/evaluation/daccriteriaforevaluatingdevelopmentassistance.htm, 2023.

- OECD-2006, “Guidance for Managing Joint Evaluations,” OECD Papers, vol. 6/2, 2006. [CrossRef]

- ASEAN-Vision, “ASEAN 2025: Forging ahead together,” Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat. Retrieved from https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/ASEAN-2025-Forging-Ahead-Together-final.pdf, 2015.

- Severino, R.C., “The ASEAN Community: Unblocking the roadblocks,” Singapore: ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Instfitute. https://www.perlego.com/book/1161272/asean-community-unblocking-the-roadblocks-pdf, 2016. [CrossRef]

- ASEAN-Secretariat-2015, “ASEAN 2025: Forging ahead together,” https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/ASEAN-2025-Forging-Ahead-Together-final.pdf, 2015.

- Simpson, B., “Pragmatism, Mead and the practice turn,” Organization Studies, vol. 30, no. 12, pp. 1329-1347., 2009. [CrossRef]

- Smith L.J., “The legal personality of the European Union and its effects on the development of space activities in Europe,” in In Schrogl KU., Pagkratis S., Baranes B. (eds) Yearbook on Space Policy 2009/2010. Yearbook on Space Policy, Vienna, Springer, 2011, pp. 199-216. [CrossRef]

- Yolles, M., Fink, G., Dauber, D., “Understanding Normative Personality,” Cybernetics and Systems, vol. 42, no. 6, pp. 447-480. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/220231517_Understanding_Normative_Personality, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Montaperto, R.N., “China-Southeast Asia Relations: Thinking Globally, Acting Regionally,” Comparative Connections, vol. 4, pp. 75-87. https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/legacy_files/files/media/csis/pubs/0404qchina_seasia.pdf, 2005.

- Rattanasevee, P., “Towards institutionalised regionalism: the role of institutions and prospects for institutionalisation in ASEAN,” Springerplus, vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 556. PMID: 25279335; PMCID: PMC4182320. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Müller, D.M., “Paradoxical Normativities in Brunei Darussalam and Malaysia: Islamic Law and the ASEAN Human Rights Declaration,” Asian Survey, vol. 56, no. 3, p. 415–441. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26364367, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Kemp, G., “Cultural Implicit Conflict: A Re-Examination of Sorokin’s Socio-Cultural Dynamics,” Journal of Conflict Processes, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 15-24, 1977.

- Vihalemm, P., Lauristin, M., Tallo, I., “Development of Political Culture in Estonia,” in In Return to the Western World - Cultural and Political Perspectives on the Estonian Post-Communist Transition, Tartu: Tartu University Press, Tartu University Press, 1997, pp. 197-210.

- Nguyen, N.T.D., Aoyama, A., “Does the Hybridizing of Intercultural Potential Facilitate Efficient Technology Transfer? An Empirical Study on Japanese Manufacturing Subsidiaries in Vietnam,” Asian Social Science, vol. 8, no. 11, pp. )26-43. https://citeseerx.ist.psu., 2012. [CrossRef]

- Yolles, M.I., Fink, G., “Generic Agency Theory, Cybernetic Orders and New Paradigms,” The Organisational, Coherence and Trajectory (OCT) Project, http://www.octresearch.net. Available July 7, 2014. at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2463270, 2014.

- Dempster, B., “Post-normal science: Considerations from a poietic systems perspective,” School of Planning, University of Waterloo, online publications., Waterloo, Canada, 1999.

- Tognetti, S.S., “Science in a double-bind: Gregory Bateson and the origins of postnormal science,” Futures, vol. 31, pp. 689–703. See www.sylviatognetti.org/data/tognetti1999.pdf, accessed June 2008., 1999. [CrossRef]

- Yolles, M., Fink, G., Dauber, D., “Understanding organisational culture as a trait theory,” European Journal of International Management, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 199-220. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Nulad, E., “The ASEAN human rights declaration and the implications of recent Southeast Asian initiatives in human rights institution-building and standard-setting,” International Journal of Human Rights, vol. 17, no. 5/6, pp. 662-678. https://doi.org/10.1080, 2013.

- CoFR, “Global governance monitor: Public health,” Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/interactives/global-governance-monitor#!/public-health, 2014.

- Kemp, S., “The ASEAN way and regional security cooperation: The case of ARF,” Pacifica Review: Peace, Security & Global Change, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 217-231. 1997. [CrossRef]

- Leifer, M., “The paradox of ASEAN,” The Round Table, vol. 68, no. 271, pp. 261-268, 1978. [CrossRef]

- Hazri, T.A., “The Rohingyas and the Paradox of ASEAN Integration, Islam and Contemorary Issues,” Malaysia Bulletin, no 25, p. https://www.academia.edu/13728756/The_Rohingyas_and_the_Paradox_of_ASEAN_Integration, March-April 2015.

- Davies, M., Ritual and Region: The Invention of ASEAN, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Seixas, P. C., Mendes, N. C., Lobner, N., The Paradox of ASEAN Centrality: Timor-Leste Betwixt and Between, Leiden, Netherlands: Brill. https://brill.com/display/title/60399, 2023.

- Goh. K., “The ASEAN Way. Non-Intervention and ASEAN's Role in Conflict Management,” Stanford Journal of East Asian Affairs Volume 3, Number, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 113-122. https://web.stanford.edu/group/sjeaa/journal3/geasia1.pdf, 2003.

- Biziouras, N., “Constructing a Mediterranean Region in Comparative Perspective: The Case of ASEAN,” University of California, Institute of European Studies, Med Conference Draft Paper, Berkeley, 2002.

- Jackson, V., “Relational peace versus pacific primacy: Configuring US strategy for Asia's regional order,” Asian Politics & Policy, vol. 15, p. 141–152. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/aspp.12675, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Sucharitkul, S., “Asean Society, a Dynamic Experiment for South-East Asian Regional Co-Operation,” in . In K. S. Sik, M. C. W. Pinto, & J. J. G. Syatauw (Eds.). Asian Yearbook of International Law, Volume 1, Brill, 1993, p. 113–148. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctv2gjwsxk.8.

- Acharya, A. and Johnston, A.I., “Comparing regional institutions: An introduction,” in In A. Acharya, A.I. Johnston (eds.) Crafting Cooperation. Regional International Institutions in Comparative Perspective, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2007, pp. 1-33. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/crafting-cooperation/comparing-regional-institutions-an-introduction/56D70F85A52A72FAB24C75E5E635ADEE.

- Kurus, B., “Understanding ASEAN: Benefits and Raison d’Etre,” Asian Survey, vol. 33, no. 8, p. 819–831. 1993. [CrossRef]

- Peoples, D., “Revised role for Buddhism in ASEAN: Conquering the education crisis,” ASEAN Library. http://asean.dla.go.th/download/attachment/20170613/48CFB86D-D0E3-4EA0-0471-98013D03BC67_Revised_Role_for_Buddhism_in_ASEAN_Conquering_the_Education_Crisis.pdf, 2015.

- Kittiprapas, S., “Buddhist Sustainable Development Through Inner Happiness,” , International Research Associates for Happy Societies (IRAH). https://www.happysociety.org/downloads/index/9502/HsoDownload , Bangkok, Thailand, 2016.

- Goh, E., “Great Powers and Hierarchical Order in Southeast Asia: Analyzing Regional Security Strategies,” International Security, vol. 32, no. 3, pp. 113-157. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwj1o7ys8uz-AhXTFcA, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Sangaji, R., “How to Do Business in Southeast Asia?,” Bright Indonesia, pp. https://brightindonesia.net/2021/01/21/how-to-do-business-in-southeast-asia/, 21 January 2021.

- Antolik, M., ASEAN and the Diplomacy of Accommodation, New York. https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/ASEAN_and_the_Diplomacy_of_Accommodation/FszxDwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1: East Gate Books, 1990.

- Anantasirikiat, S., “The Evolution of Thai-Style Public Diplomacy,” in in Chia, S.A. (Ed), Winning Hearts and Minds: Public Diplomacy in ASEAN, Singapore, The Nutgraf, 2021, pp. 94-102. [CrossRef]

- Misalucha, C.G., “Southeast Asia-US Relations: Hegemony or Hierarchy?,” Contemporary Southeast Asia, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 209-228. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41288827, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Dashineau, S.C., Edershile, E.A., Simms, L.J., Wright, A.G.C., “Pathological narcissism and psychosocial functioning,” Personal Disord, vol. 10, no. 5, pp. 473-478. Epub 2019 Jul 1. PMID: 31259606; PMCID: PMC6710132. https://www.ncbi.nlm.n, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Nair, D., “Saving the States’ Face: An Ethnography of the ASEAN Secretariat and Diplomatic Field in Jakarta,” Doctoral Thesis, Department of International Relations of the London School of Economics, London. http://etheses.lse.ac.uk/3176/1/Nair_Savin, London, 2015.

- Vaknin, S., “Dissociation and Confabulation in Narcissistic Disorders,” J. Addict Addictv Disord, vol. 7, no. 39, pp. https://www.heraldopenaccess.us/openaccess/dissociation-and-confabulation-in-narcissistic-disorders, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Jetschke, A., “Institutionalizing ASEAN: celebrating Europe through network governance,” Cambridge Review of International Affairs, vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 407-426. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.L., “Perceived self-efficacy and phobic disability,” in in Schwarzer, R. (Ed.): Self-Efficacy: Thought Control of Action, Hemisphere, Washington, DC, Taylor Francis, 1992, p. 149–176. https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/2375268.

- Bandura, A., Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory, Engewood Cliffs, USA. . https://www.worldcat.org/title/social-foundations-of-thought-and-action-a-social-cognitive-theory/oclc/1209442812: Prentice-Hall, 1986.

- Bandura, A., “Social cognitive theory of personality,” in In L. Pervin & O. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality 2nd ed., Guilford, UK, Guilford Publications, 1999, pp. 154-196. https://www.uky.edu/~eushe2/Bandura/Bandura1999HP.pdf3.

- Benny, G., Rashila, R., Tham, S. Y., “Public Opinion on the Formation of the ASEAN Economic Community: An Exploratory Study in Three ASEAN Countries,” International Journal of Asia Pacific Studies, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 85–114, 2015.

- Inama, S., Sim E. W., The Foundation of the ASEAN Economic Community: An Institutional and Legal Profile, Cambridge/New York/ Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- Mason, D. S., “Political culture and political change in post-communist societies,” in In A. Brown (Ed.), Political culture and communist studies, London, Macmillan, 2008, pp. 1-22.

- Roberts, C.B., “Weak states’ regionalism: ASEAN and the limits of security cooperation in Pacific Asia,” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 209-240. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280737296_Weak_states%27_regionalism_ASEAN_and_the_limits_of_security_cooperation_in_Pacific_Asia, 2012.

- Ayoob, M., “Subaltern realism: international relations theory meets the third world,” in In International Relations Theory and the Third World, Edited by: G Neuman, Stephanie, Basingstoke, UK, Macmillan, 1998, p. 31–54.

- ASEAN-inception, “The Founding of ASEAN, https://asean.org/the-founding-fof-asean/,” ASEAN, 2020.

- Angresano, J., “European Union integration lessons for ASEAN+3: the importance of contextual specificity,” Journal of Asian Economics, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 479-496., 2006.

- Letiche, J.M., The Asian economic catharsis: how Asian firms bounce back from crisis, Westport, CT: Praeger, 2000.

- Narine, S., “ASEAN in the twenty-first century: a sceptical review,” Cambridge Review of International Affairs, vol. 22, p. 369–386. https://www.academia.edu/52019367/ASEAN_in_the_twenty_first_century_a_sceptical_review, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Heydarian, R.J., “ASEAN-China Code of Conduct: Never-ending negotiations,” The Straits Times, pp. https://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/asean-china-code-of-conduct-never-ending-negotiations, 9 March 2017.

- Seng, T.S., “Commentary: ASEAN can do better on Myanmar this time,” Channelnewsasia, pp. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/commentary/myanmar-coup-junta-military-aung-san-ASEAN-14111926, 5 February 2021.

- Pongsudhirak, T., “The global tremors of Myanmar’s coup,” Project Syndicate, pp. https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/myanmar-coup-international-response-asean-by-thitinan-pongsudhirak-2021-04, 2 April 2021.

- Tan, S.S., “ASEAN’s response to Covid-19: Underappreciated but insufficient. ISEAS,” Perspective, vol. 2021, no. 11, pp. 1-10., 2021.

- Kliem, F., “ASEAN and the EU amidst COVID-19: overcoming the self-fulfilling prophecy of realism,” Asia Europe Journal, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 371-389., 2021. [CrossRef]

- Almuttaqi, I., “Asean holds special coronavirus summit, but will its plans come to fruition?,” South China Morning Post, pp. https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/politics/article/3079899/asean-holds-special-coronavirus-summit-will-blocs, 14 April 2020.

- Buendia, R.G., “ASEAN ‘Cohesiveness and Responsiveness’ and Peace and Stability in Southeast Asia,” E-International Relations, pp. https://www.e-ir.info/2020/07/21/can-asean-cohesiveness-and-responsiveness-secure-peace-and-stability-in-southeast-asia/, 21 July 2020.

- Jones, D.M., Jenne, N., “China’s five principles of peaceful coexistence: a historical perspective,” in In S. Tiezzi & S. M. Pekkanen (Eds.), China’s rise and rebalance in Asia: implications for regional security, London, Routledge, 2015, pp. 13-32.

- Putra, A.S., Suryadinata, L., Hwang, J.C., “The South China Sea dispute: ASEAN’s role and challenges,” in In L. Suryadinata (Ed.), The 21st century maritime Silk Road: challenges and opportunities for Asia and Europe, London, Routledge, 2019, pp. 67-86.

- Gamas, J.H.D., “The tragedy of the Southeast Asian commons: ritualism in ASEAN’s response to the South China Sea maritime dispute,” European Journal of East Asian Studies, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 33-54, 2014.

- Heydarian, R.J., “Tragedy of small power politics: Duterte and the shifting sands of Philippine foreign policy,” The Pacific Review, vol. 30, no. 6, pp. 923-938. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Keling, M.F., Shuib, M.S., Ajis, M.N., Sani, M.A.M., “The ASEAN way: The role of non-interference policy in preserving the stability of the region,” Journal of Asia Pacific Studies, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 232-247. http://www.japss.org/upload/12.Keling%20et%20a, 2011.

- Biziouras, N., “Constructing a Mediterranean region in comparative perspective: The case of ASEAN,” in Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, Boston, MA. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Constructing-a-Mediterranean-Region-in-Comparative-Biziouras/056cb0ffeedb348edfa8646e47525482c8b91a05, 2002.

- Antolik, M., ASEAN and the diplomacy of accommodation. M.E. Sharpe., Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, 1990.

- Ratcliffe, R., “Genocide case against Myanmar over Rohingya atrocities cleared to proceed,” The Guardian, pp. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/jul/22/genocide-case-against-myanmar-over-rohingya-atrocities-cleared-to-proceed, 22 July 2022.

- Min, C.H., “ASEAN agrees in principle to admit Timor-Leste as 11th member,” China News Agency, pp. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/asia/timor-leste-asean-summit-2022-member-observer-status-306370, 11 November 2022.

- Kleimberg, L., “Some reflections on the connections between aggression and depression,” in in Harding, C. (Ed.). Psychoanalytic Perspectives, Hove, UK and New York, USA, Routledge, 2006, pp. 181-193. Available through https://books.google.co.uk/.

- Collins, A., “A people-oriented ASEAN: A door ajar or closed for civil society organisations?,” Contemporary Southeast Asia, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 313-331, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, M.M., Assimilation in American life: The role of race, religion, and national origins, Oxford.. https://www.worldcat.org/title/assimilation-in-american-life-the-role-of-race-religion-and-national-origins/oclc/1144769: Oxford University Press, 1964.

- Thompson, D., Chong, B., “Built for Trust, Not for Conflict: ASEAN Faces the Future,” US Institute of Peace. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep26022, 2020.

- Hudson, V. M., Caprioli, M., Ballif-Spanvill, B., McDermott, R., Emmett, C. F., “The heart of the matter: The security of women and the security of states,” International Security, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 7-45., 2019. [CrossRef]

- Lebow, R. N., & Stein, J. G. , “Deterrence: The elusive dependent variable,” World Politics, vol. 42, no. 3, pp. 336-369, 1990. [CrossRef]

- Wendt, A., Social theory of international politics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press., 1999.

- Acharya, A., Constructing a security community in Southeast Asia: ASEAN and the problem of regional order, London and New York: Routledge., 2001.

- Acharya, A., The end of American world order, Cambridge and Boston: Polity Press., 2014.