Submitted:

29 May 2023

Posted:

30 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

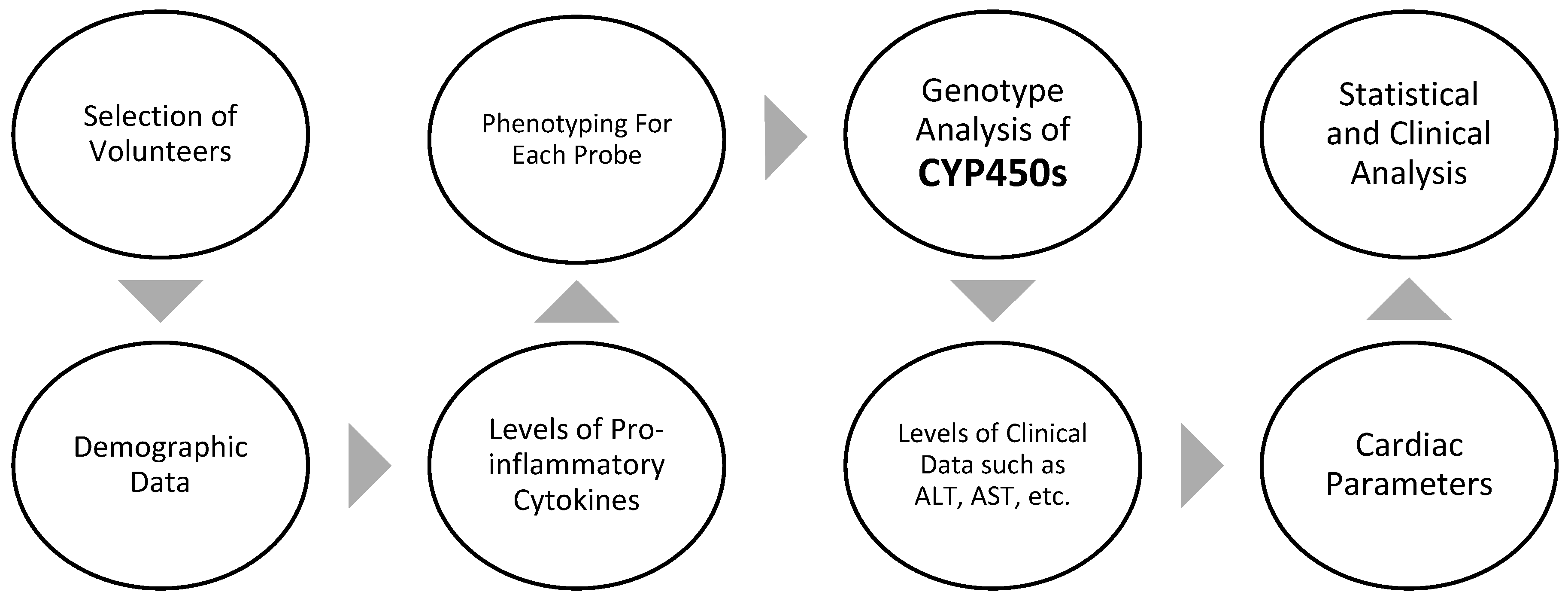

Methods

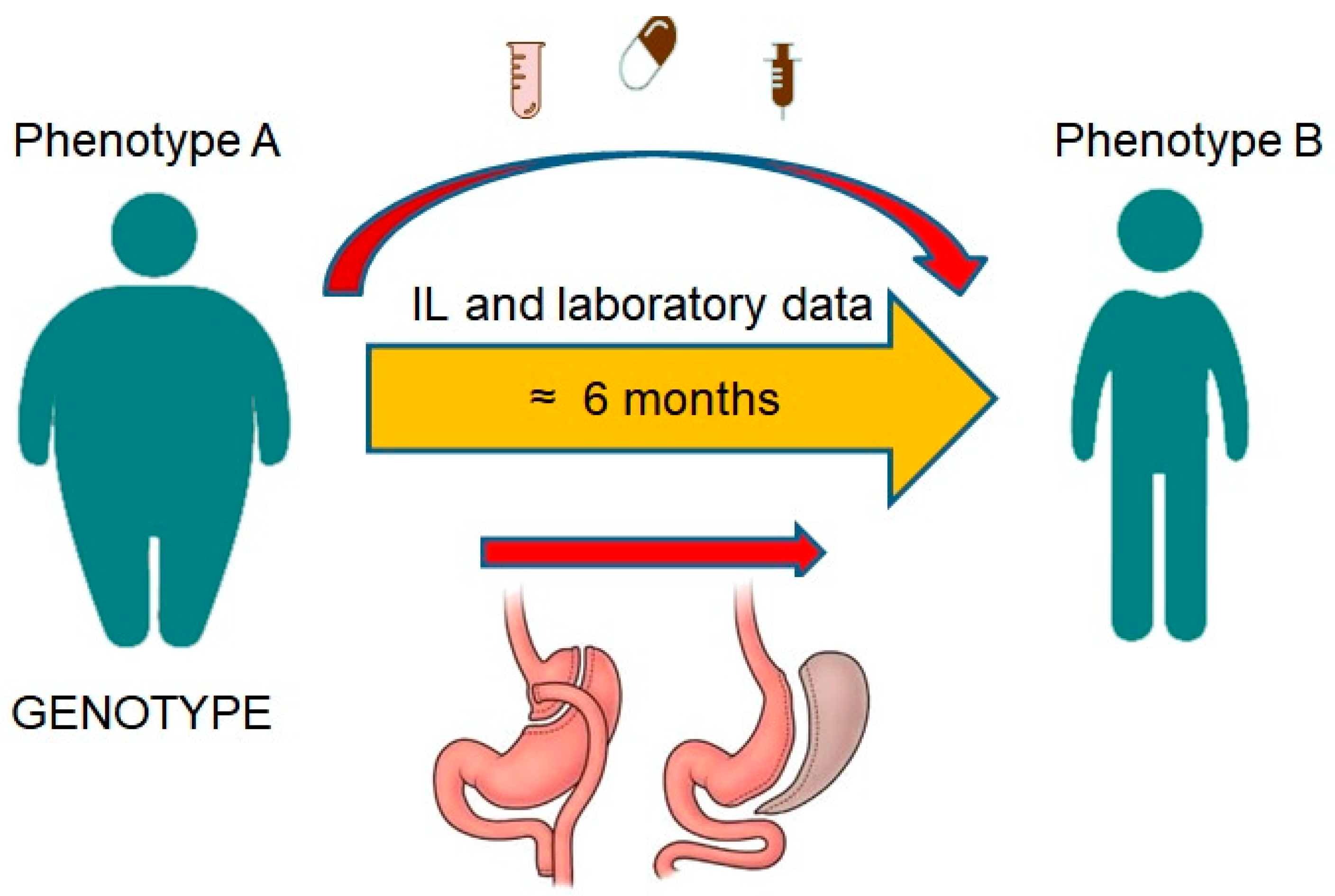

Study Design and Population

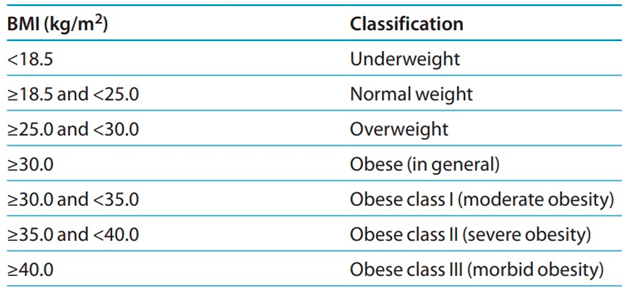

- Adolescent volunteers having a BMI of < 25 and severely obese patients with a BMI of ≥ 40 who are candidates for bariatric surgery

- between the ages of 18 and 60

- HbA1C < 6.5%

- All Healthy and obese individuals alike must not have active cases of thyroid illness, cirrhosis, IBD, Helicobacter pylori infection, or any other infectious disease (now or during the last four weeks).

- Participants taking medications believed to influence metabolic activity, including corticosteroids or NSAIDs used for their anti-inflammatory effects, will not be allowed to participate in this study.

- Females will be questioned regarding having a normal menstrual cycle and will be disqualified if they are pregnant or breastfeeding.

- Individuals who are often treated with drugs that have an inhibitory or stimulating impact on DMEs and whose substrates are implemented in the phenotyping cocktail

- Patients who have previously had hypersensitivity to any of the drugs in the combination

- Patients who had organ transplant surgeries

- Patients with an active cancer

- Participants who had been heavy smokers or alcoholics for at least two months before the research.

Ethical approval

Cocktail administration

Laboratory sample analysis

Data Management

Statistical analysis

Safety

Results

Demographic and paraclinical results

Cardiac results

Pro-inflammatory cytokines results

Genotype results

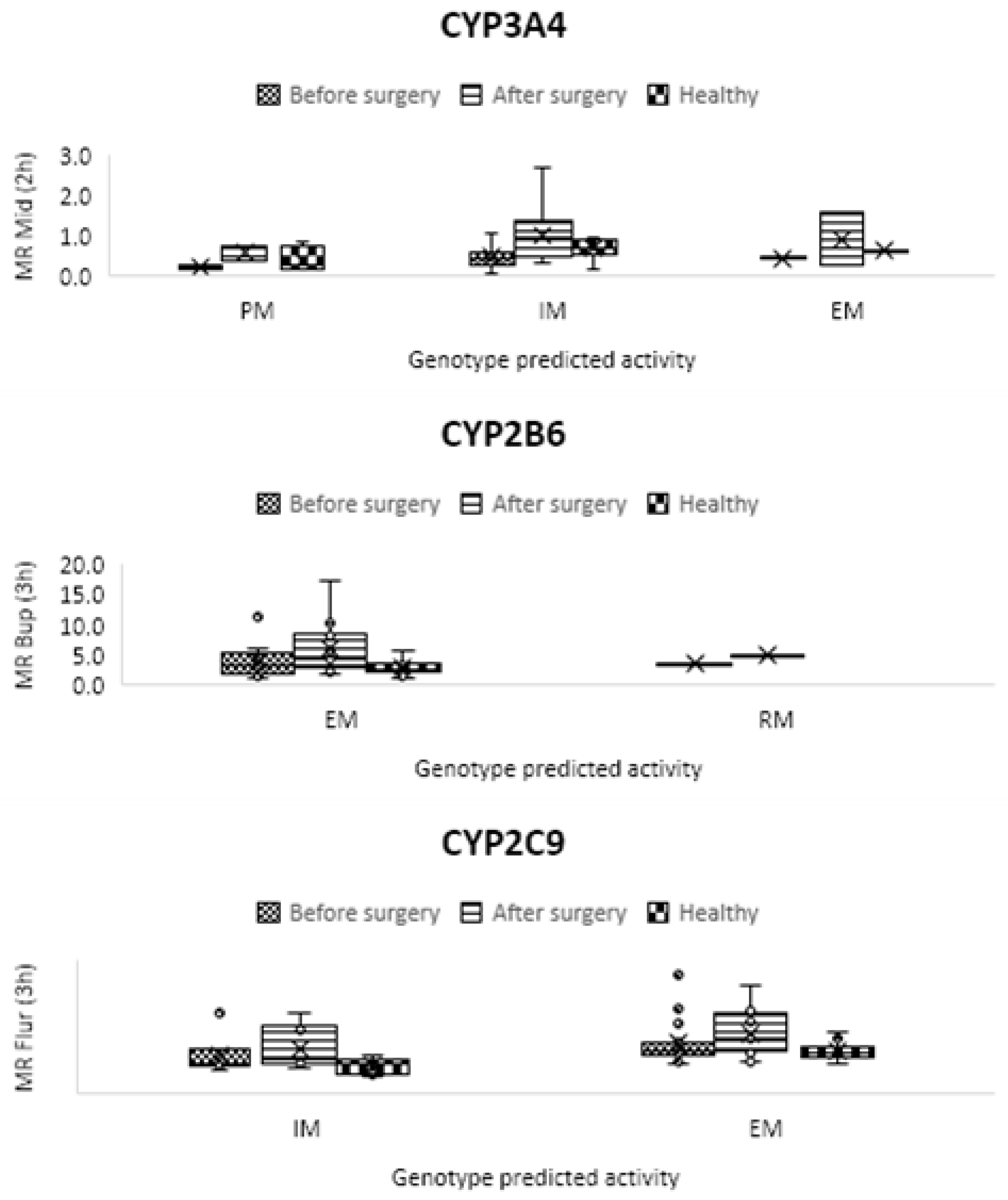

Phenotype results

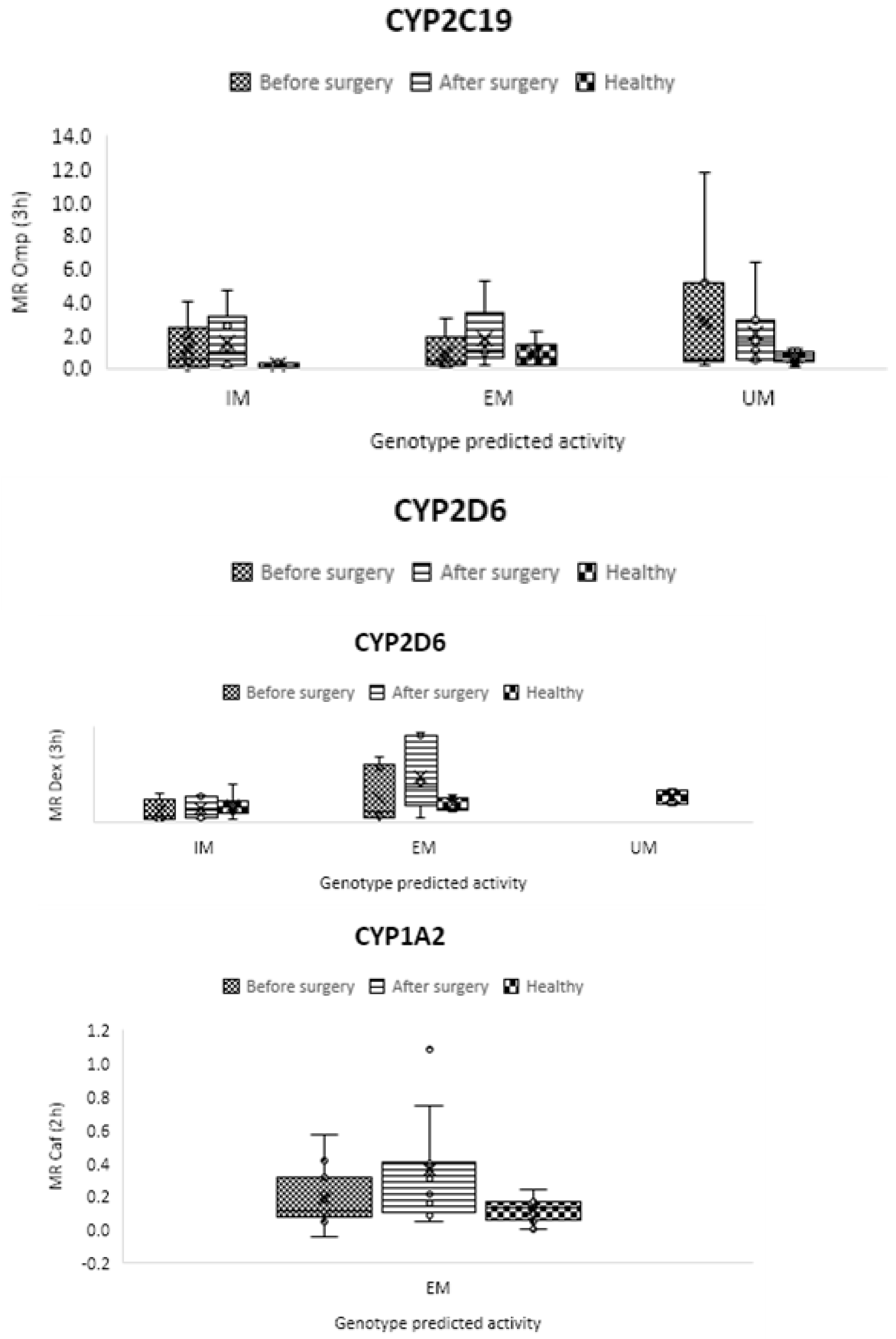

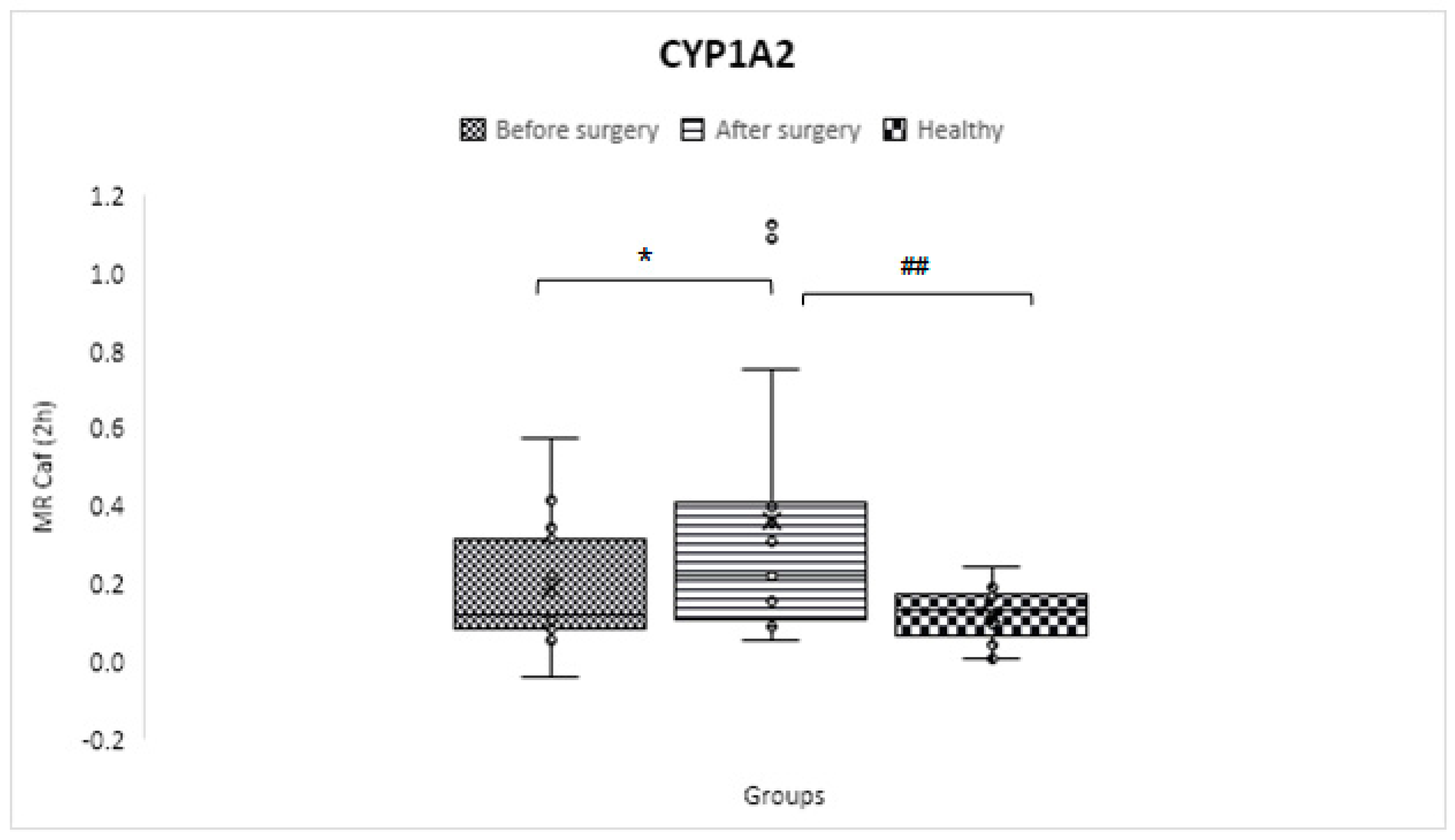

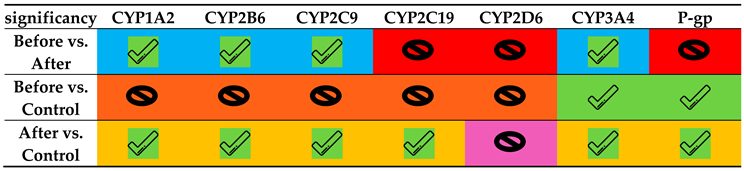

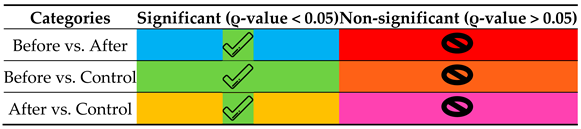

CYP1A2

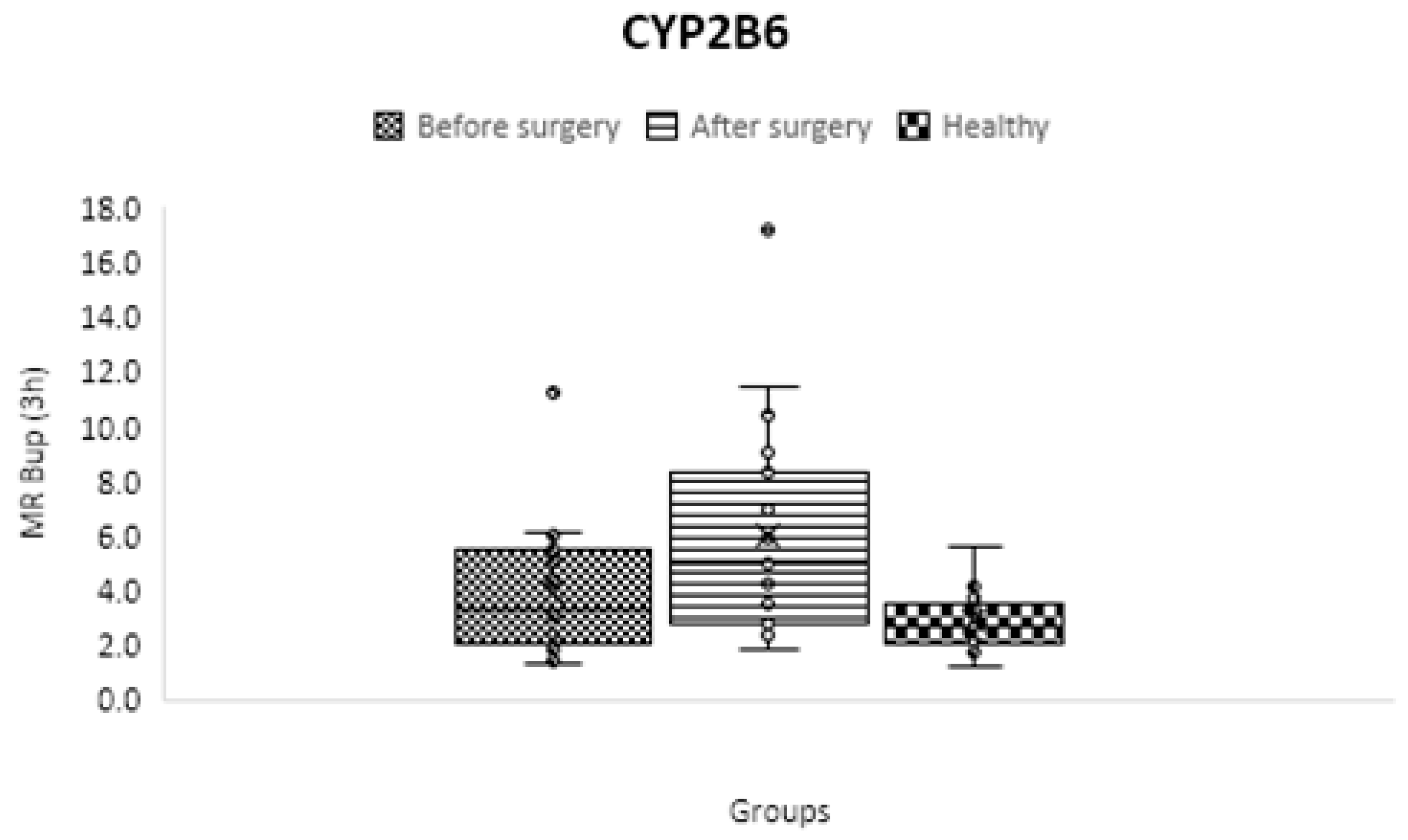

CYP2B6

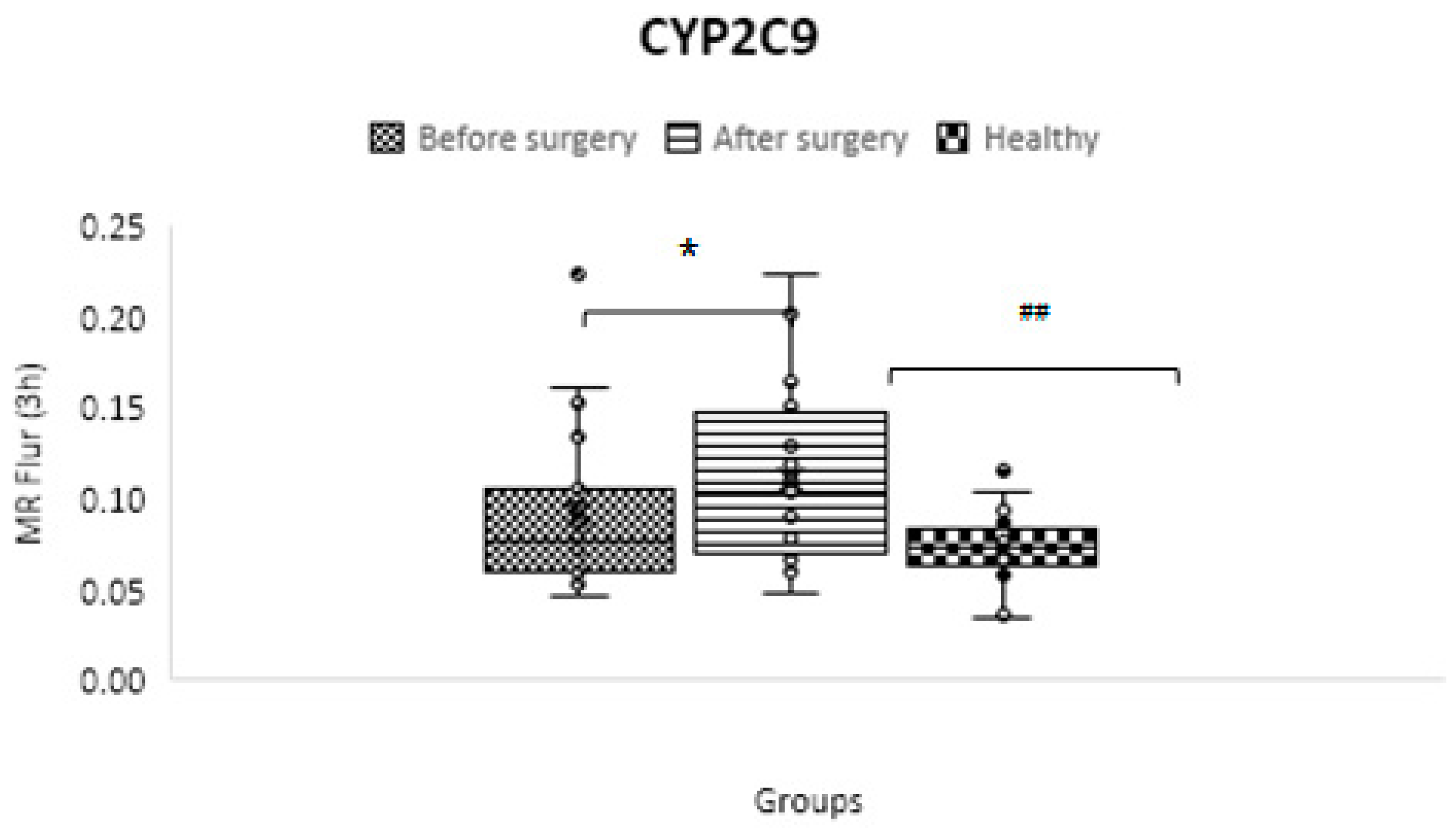

CYP2C9

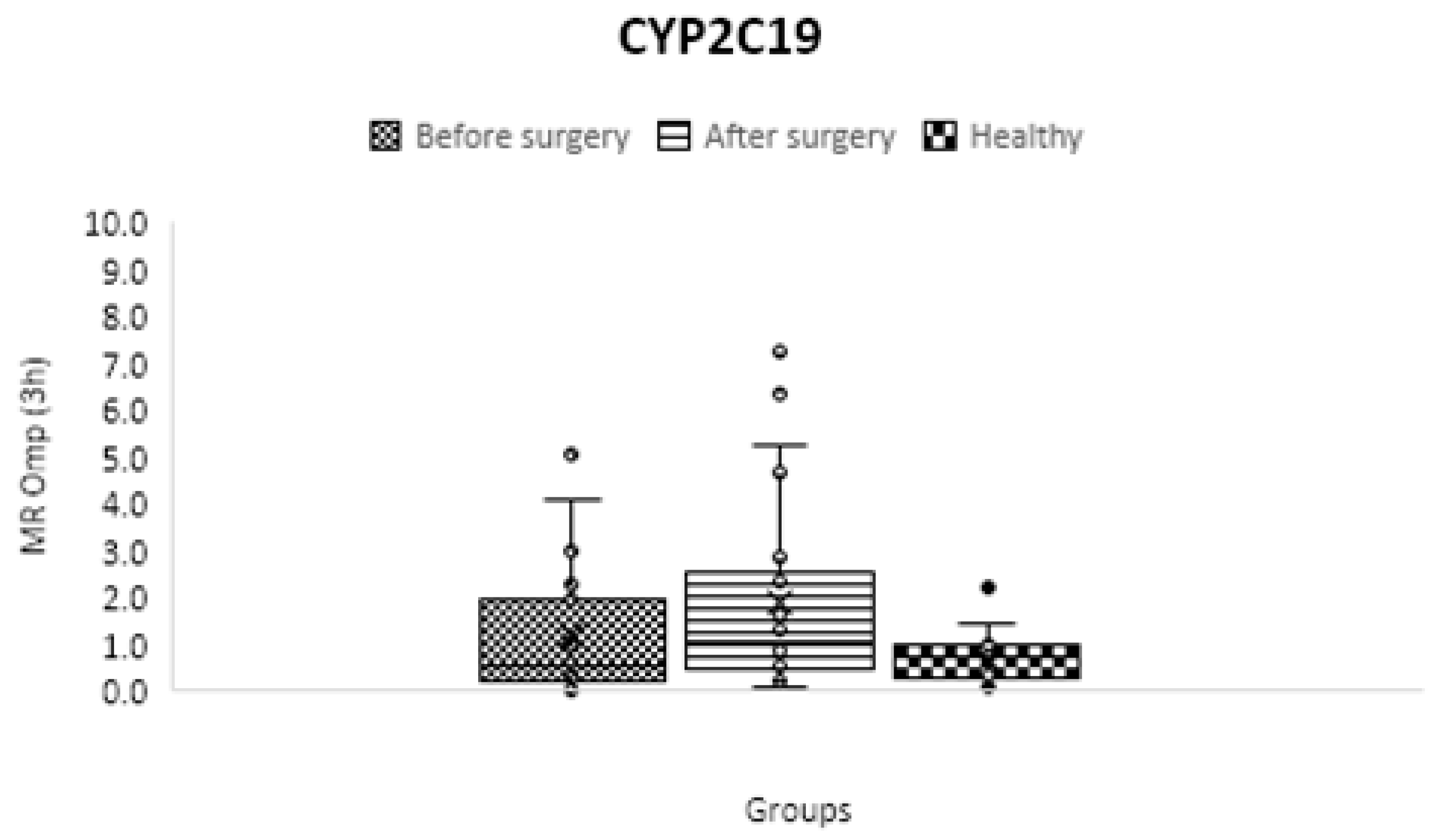

CYP2C19

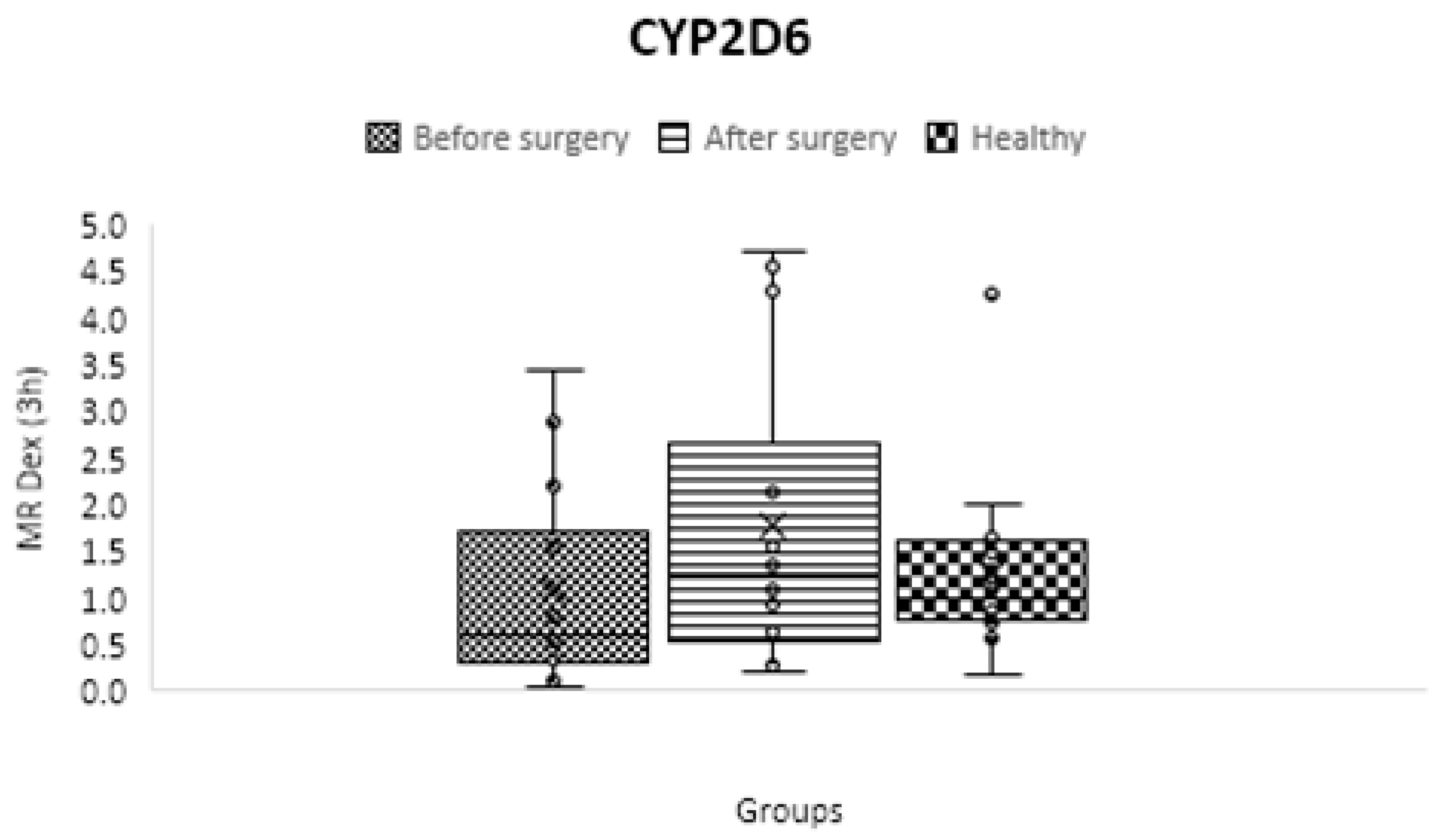

CYP2D6

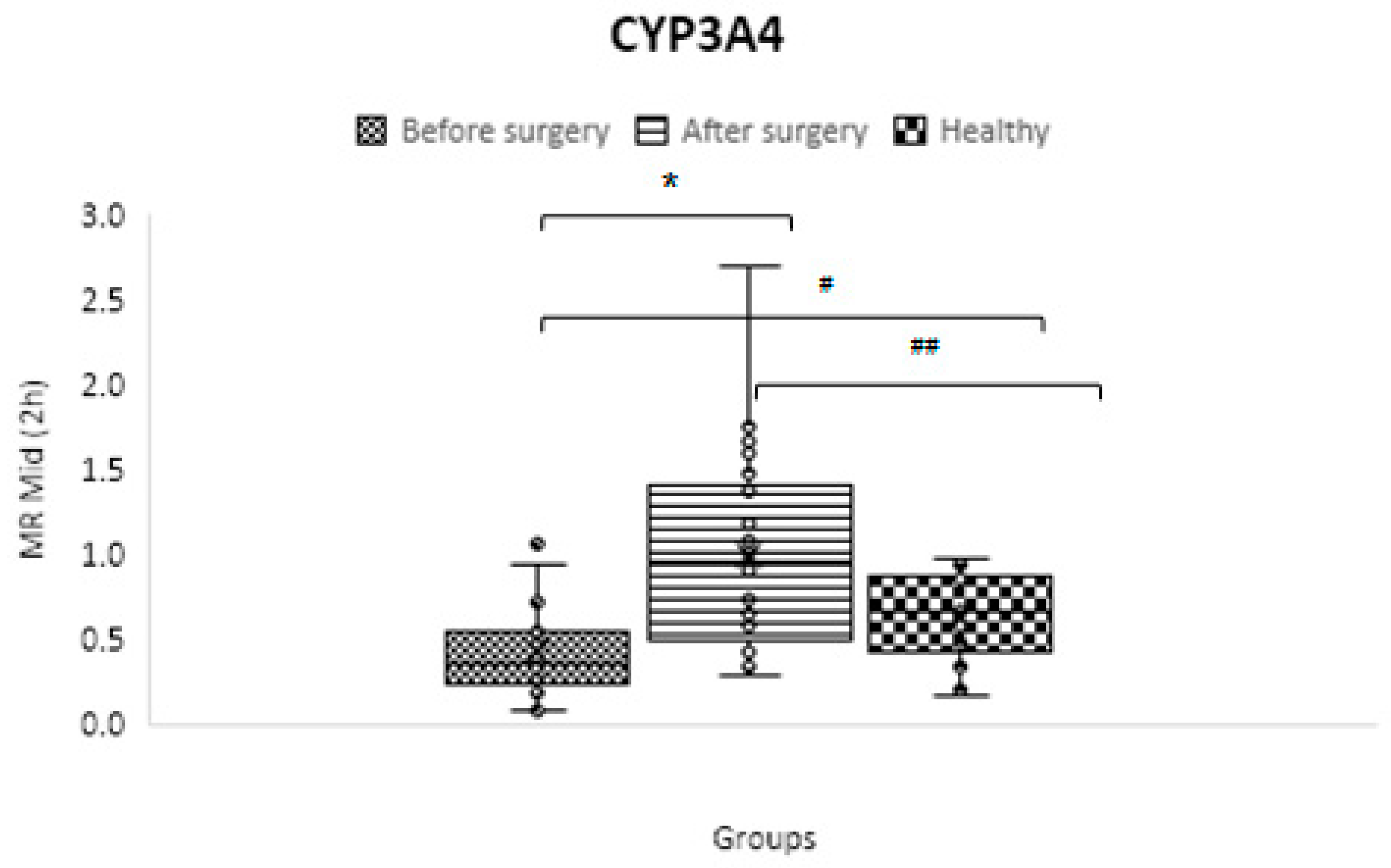

CYP3A4/5

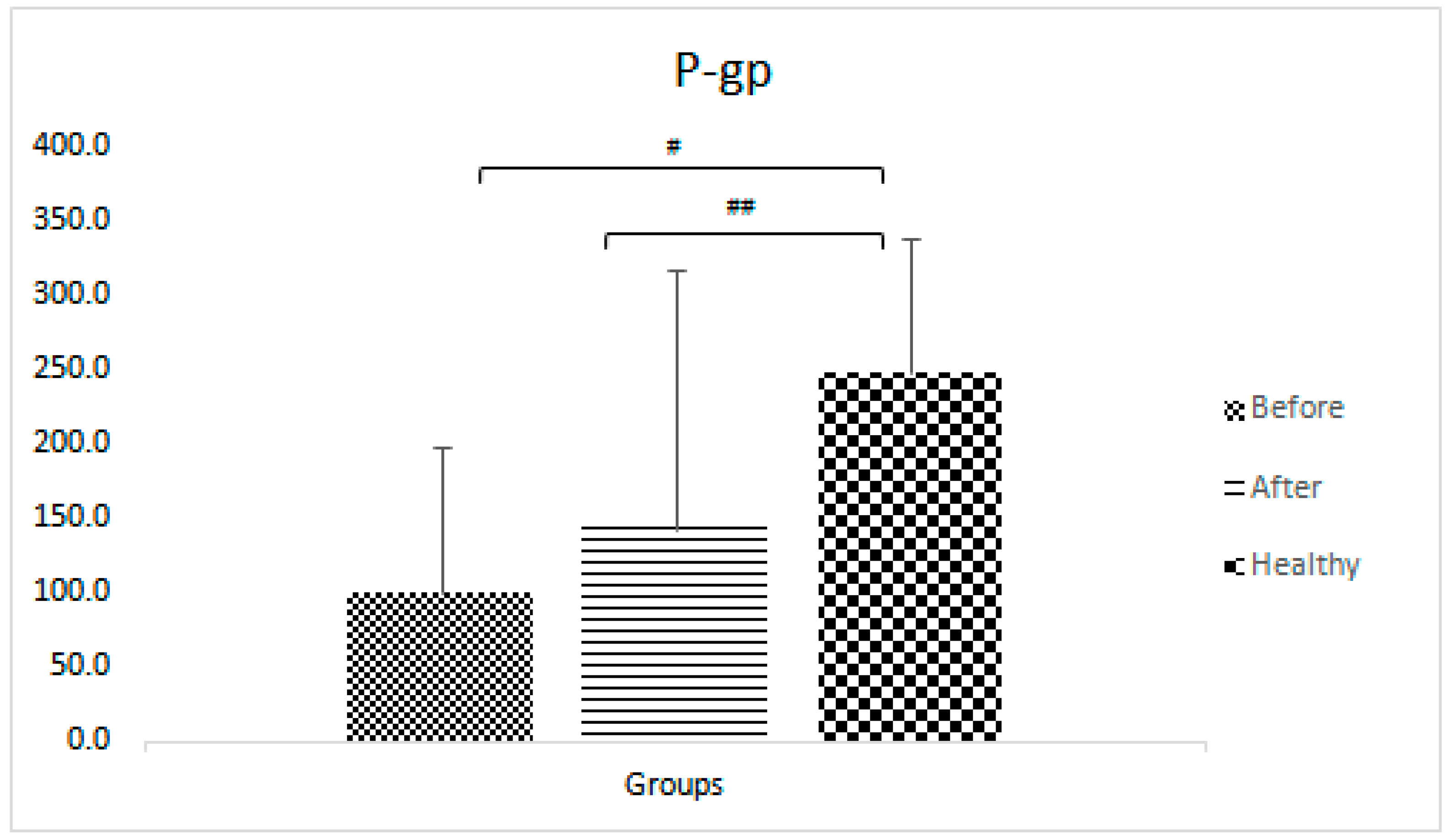

P-gp pump

Discussion

Strengths and weaknesses of the project

Acknowledgements

Organization and Budget provision

Disclosures

References

- Klomp, S.D.; Manson, M.L.; Guchelaar, H.J.; Swen, J.J. Phenoconversion of Cytochrome P450 Metabolism: A Systematic Review. J Clin Med 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesche, D.; Mostafa, S.; Everall, I.; Pantelis, C.; Bousman, C.A. Impact of CYP1A2, CYP2C19, and CYP2D6 genotype- and phenoconversion-predicted enzyme activity on clozapine exposure and symptom severity. Pharmacogenomics J 2020, 20, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.R.; Smith, R.L. Addressing phenoconversion: the Achilles' heel of personalized medicine. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2015, 79, 222–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.R.; Smith, R.L. Inflammation-induced phenoconversion of polymorphic drug metabolizing enzymes: hypothesis with implications for personalized medicine. Drug Metab Dispos 2015, 43, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenoir, C.; Daali, Y.; Rollason, V.; Curtin, F.; Gloor, Y.; Bosilkovska, M.; Walder, B.; Gabay, C.; Nissen, M.J.; Desmeules, J.A.; et al. Impact of Acute Inflammation on Cytochromes P450 Activity Assessed by the Geneva Cocktail. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2021, 109, 1668–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, R.R.; Gaedigk, A. Precision medicine: does ethnicity information complement genotype-based prescribing decisions? Therapeutic advances in drug safety 2018, 9, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

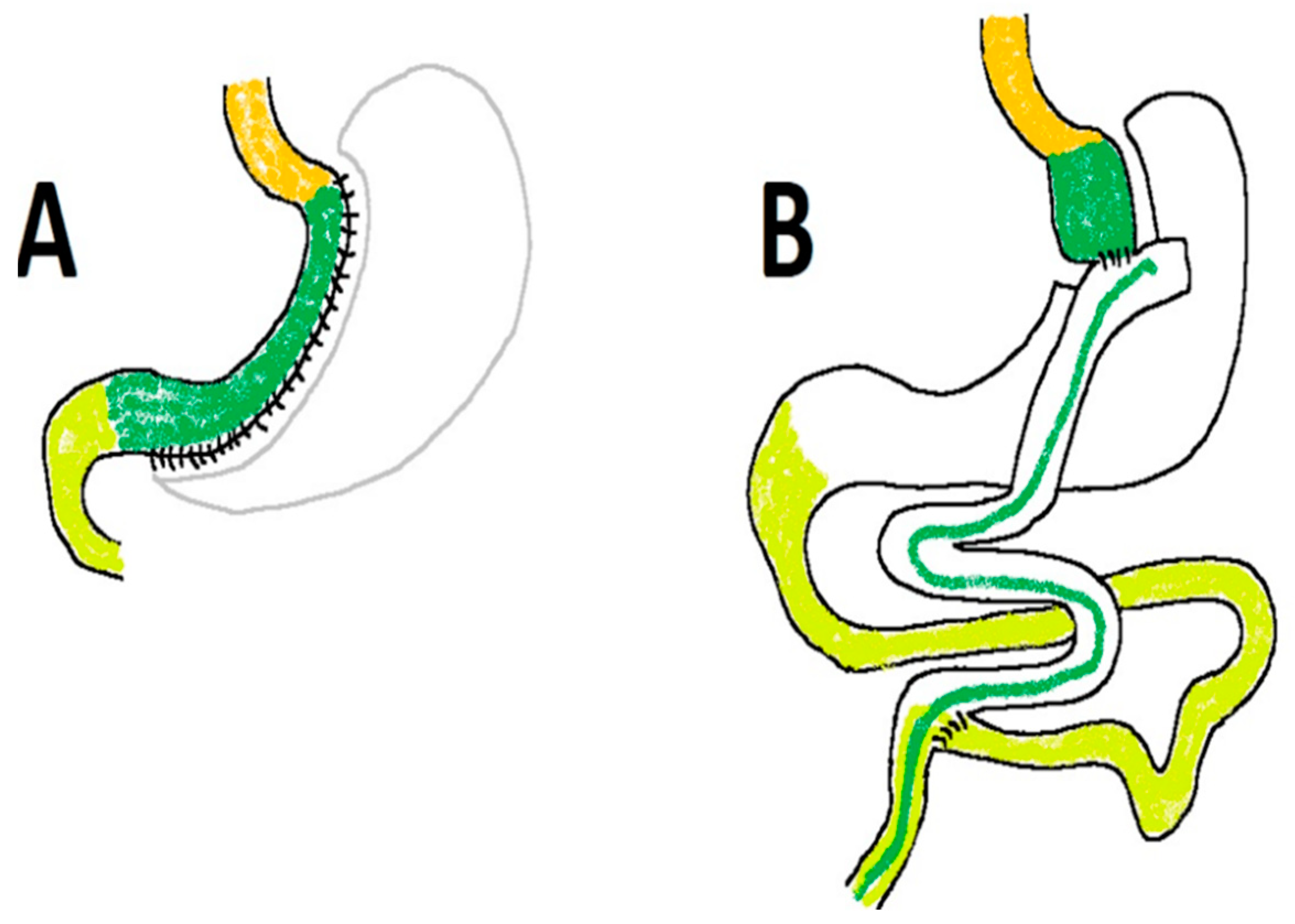

- Puris, E.; Pasanen, M.; Ranta, V.P.; Gynther, M.; Petsalo, A.; Kakela, P.; Mannisto, V.; Pihlajamaki, J. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery influenced pharmacokinetics of several drugs given as a cocktail with the highest impact observed for CYP1A2, CYP2C8 and CYP2E1 substrates. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2019, 125, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porazka, J.; Szalek, E.; Polom, W.; Czajkowski, M.; Grabowski, T.; Matuszewski, M.; Grzeskowiak, E. Influence of Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus on the Pharmacokinetics of Tramadol After Single Oral Dose Administration. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 2019, 44, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salici, A.G.; Sisman, P.; Gul, O.O.; Karayel, T.; Cander, S.; Ersoy, C. The prevalence of obesity and related factors: An urban survey study. 2017.

- Jain, R.; Chung, S.M.; Jain, L.; Khurana, M.; Lau, S.W.; Lee, J.E.; Vaidyanathan, J.; Zadezensky, I.; Choe, S.; Sahajwalla, C.G. Implications of obesity for drug therapy: limitations and challenges. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2011, 90, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elrazek, A.E.; Elbanna, A.E.; Bilasy, S.E. Medical management of patients after bariatric surgery: Principles and guidelines. World J Gastrointest Surg 2014, 6, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, C.M.; Quidley, A.M.; Love, B.L.; Yeager, C.; McMichael, B.; Bookstaver, P.B. Long-term pharmacotherapy considerations in the bariatric surgery patient. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2016, 73, 1230–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brocks, D.R.; Ben-Eltriki, M.; Gabr, R.Q.; Padwal, R.S. The effects of gastric bypass surgery on drug absorption and pharmacokinetics. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 2012, 8, 1505–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.M.; An, J. Cytokines, inflammation, and pain. Int Anesthesiol Clin 2007, 45, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, L.M.; Jiskoot, W.; Swen, J.J.; Manson, M.L. Distinct Effects of Inflammation on Cytochrome P450 Regulation and Drug Metabolism: Lessons from Experimental Models and a Potential Role for Pharmacogenetics. Genes (Basel) 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosilkovska, M.; Samer, C.F.; Deglon, J.; Rebsamen, M.; Staub, C.; Dayer, P.; Walder, B.; Desmeules, J.A.; Daali, Y. Geneva cocktail for cytochrome p450 and P-glycoprotein activity assessment using dried blood spots. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2014, 96, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donzelli, M.; Derungs, A.; Serratore, M.G.; Noppen, C.; Nezic, L.; Krahenbuhl, S.; Haschke, M. The basel cocktail for simultaneous phenotyping of human cytochrome P450 isoforms in plasma, saliva and dried blood spots. Clin Pharmacokinet 2014, 53, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tracy, T.S.; Chaudhry, A.S.; Prasad, B.; Thummel, K.E.; Schuetz, E.G.; Zhong, X.B.; Tien, Y.C.; Jeong, H.; Pan, X.; Shireman, L.M.; et al. Interindividual Variability in Cytochrome P450-Mediated Drug Metabolism. Drug Metab Dispos 2016, 44, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosilkovska, M.; Samer, C.; Deglon, J.; Thomas, A.; Walder, B.; Desmeules, J.; Daali, Y. Evaluation of Mutual Drug-Drug Interaction within Geneva Cocktail for Cytochrome P450 Phenotyping using Innovative Dried Blood Sampling Method. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2016, 119, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasim, H.; Rouini, M.; Gholami, K.; Larti, F.; Safari, S.; Ardakani, Y.H. Evaluation of phenoconversion phenomenon in obese patients: the effects of bariatric surgery on the CYP450 activity "a protocol for a case-control pharmacokinetic study". J Diabetes Metab Disord 2021, 20, 2085–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tveden-Nyborg, P.; Bergmann, T.K.; Lykkesfeldt, J. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology Policy for Experimental and Clinical studies. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2018, 123, 233–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjelmesaeth, J.; Asberg, A.; Andersson, S.; Sandbu, R.; Robertsen, I.; Johnson, L.K.; Angeles, P.C.; Hertel, J.K.; Skovlund, E.; Heijer, M.; et al. Impact of body weight, low energy diet and gastric bypass on drug bioavailability, cardiovascular risk factors and metabolic biomarkers: protocol for an open, non-randomised, three-armed single centre study (COCKTAIL). BMJ Open 2018, 8, e021878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farnert, A.; Arez, A.P.; Correia, A.T.; Bjorkman, A.; Snounou, G.; do Rosario, V. Sampling and storage of blood and the detection of malaria parasites by polymerase chain reaction. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1999, 93, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puris, E.; Pasanen, M.; Gynther, M.; Hakkinen, M.R.; Pihlajamaki, J.; Keranen, T.; Honkakoski, P.; Raunio, H.; Petsalo, A. A liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis of nine cytochrome P450 probe drugs and their corresponding metabolites in human serum and urine. Anal Bioanal Chem 2017, 409, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosilkovska, M.; Déglon, J.; Samer, C.; Walder, B.; Desmeules, J.; Staub, C.; Daali, Y. Simultaneous LC–MS/MS quantification of P-glycoprotein and cytochrome P450 probe substrates and their metabolites in DBS and plasma. Bioanalysis 2014, 6, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravel, S.; Chiasson, J.L.; Turgeon, J.; Grangeon, A.; Michaud, V. Modulation of CYP450 Activities in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2019, 106, 1280–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiara Broccanello, L.G. , and Piergiorgio Stevanato. QuantStudio™ 12K Flex OpenArray® System as a Tool for High-Throughput Genotyping and Gene Expression Analysis, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Achour, B.; Gosselin, P.; Terrier, J.; Gloor, Y.; Al-Majdoub, Z.M.; Polasek, T.M.; Daali, Y.; Rostami-Hodjegan, A.; Reny, J.L. Liquid Biopsy for Patient Characterization in Cardiovascular Disease: Verification against Markers of Cytochrome P450 and P-Glycoprotein Activities. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2022, 111, 1268–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samer, C.F.; Lorenzini, K.I.; Rollason, V.; Daali, Y.; Desmeules, J.A. Applications of CYP450 testing in the clinical setting. Mol Diagn Ther 2013, 17, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloor, Y.; Lloret-Linares, C.; Bosilkovska, M.; Perroud, N.; Richard-Lepouriel, H.; Aubry, J.M.; Daali, Y.; Desmeules, J.A.; Besson, M. Drug metabolic enzyme genotype-phenotype discrepancy: High phenoconversion rate in patients treated with antidepressants. Biomed Pharmacother 2022, 152, 113202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desta, Z.; Gammal, R.S.; Gong, L.; Whirl-Carrillo, M.; Gaur, A.H.; Sukasem, C.; Hockings, J.; Myers, A.; Swart, M.; Tyndale, R.F.; et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guideline forCYP2B6and Efavirenz-Containing Antiretroviral Therapy. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2019, 106, 726–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theken, K.N.; Lee, C.R.; Gong, L.; Caudle, K.E.; Formea, C.M.; Gaedigk, A.; Klein, T.E.; Agundez, J.A.G.; Grosser, T. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guideline (CPIC) for CYP2C9 and Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2020, 108, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crews, K.R.; Monte, A.A.; Huddart, R.; Caudle, K.E.; Kharasch, E.D.; Gaedigk, A.; Dunnenberger, H.M.; Leeder, J.S.; Callaghan, J.T.; Samer, C.F.; et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guideline for CYP2D6, OPRM1, and COMT Genotypes and Select Opioid Therapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2021, 110, 888–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.A.; Sangkuhl, K.; Stein, C.M.; Hulot, J.S.; Mega, J.L.; Roden, D.M.; Klein, T.E.; Sabatine, M.S.; Johnson, J.A.; Shuldiner, A.R.; et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guidelines for CYP2C19 genotype and clopidogrel therapy: 2013 update. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2013, 94, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preissner, S.C.; Hoffmann, M.F.; Preissner, R.; Dunkel, M.; Gewiess, A.; Preissner, S. Polymorphic cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYPs) and their role in personalized therapy. PloS one 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandra, S.; Chalasani, N.; Jones, D.R.; Mattar, S.; Hall, S.D.; Vuppalanchi, R. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic alterations in the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass recipients. Ann Surg 2013, 258, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloret-Linares, C.; Daali, Y.; Abbara, C.; Carette, C.; Bouillot, J.-L.; Vicaut, E.; Czernichow, S.; Declèves, X. CYP450 activities before and after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: correlation with their intestinal and liver content. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases 2019, 15, 1299–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyshaburinezhad, N.; Shirzad, N.; Rouini, M.; Namazi, S.; Khoshayand, M.; Esteghamati, A.; Nakhjavani, M.; Ghasim, H.; Daali, Y.; Ardakani, Y.H. Evaluation of important human CYP450 isoforms and P-glycoprotein phenotype changes and genotype in type 2 diabetic patients, before and after intensifying treatment regimen, by using Geneva cocktail. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenoir, C.; Terrier, J.; Gloor, Y.; Gosselin, P.; Daali, Y.; Combescure, C.; Desmeules, J.A.; Samer, C.F.; Reny, J.L.; Rollason, V. Impact of the Genotype and Phenotype of CYP3A and P-gp on the Apixaban and Rivaroxaban Exposure in a Real-World Setting. J Pers Med 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel Porat, O.D. , Ella Vainer, Sandra Cvijić, and Arik Dahan. Antiallergic Treatment of Bariatric Patients: Potentially Hampered Solubility/Dissolution and Bioavailability of Loratadine, but Not Desloratadine, Post-Bariatric Surgery. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2022, 19, 2922–2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagman, D.K.; Larson, I.; Kuzma, J.N.; Cromer, G.; Makar, K.; Rubinow, K.B.; Foster-Schubert, K.E.; van Yserloo, B.; Billing, P.S.; Landerholm, R.W.; et al. The short-term and long-term effects of bariatric/metabolic surgery on subcutaneous adipose tissue inflammation in humans. Metabolism 2017, 70, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

| Parameters | Healthy participants | Obese patients before treatment | Obese patients after treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| No (%) of subjects | 21 | 24 | |

| Sex No. (%) M: F | 14:7 (67:33) | 3:21 (13:87) | |

| Age (years) | 30 ± 8.9 | 36.6 ± 8.7 | |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 24.3 ± 3.0 | 45.1 ± 4.2 * | 32.5 ± 3.6 * |

| High blood pressure No. (%) | 0 | 2 (8.3) | |

| Fatty liver No. (%) | 0 | 3 (12.5) | |

| ESR (mm/Hr) | - | 30.1 ± 15.7 | 20.2 ± 18.1 * |

| AST (U/L) | - | 20.9 ± 7.8 | 16.8 ± 4.6 * |

| ALT (U/L) | - | 26.6 ± 13.9 | 15.7 ± 5.9 * |

| HbA1c (%) | - | 5.3 ± 0.5 | 5.0 ± 0.4 * |

| TSH (micIU/ml) | - | 4.3 ± 4.1 | 2.4 ± 1.3 |

| Cr (mg/dL) | - | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 |

| Smokers No. (%) | 0 | 12 (50) | |

| Alcohol cons. No. (%) | 0 | 4 (16.7) | |

| SV-index (cc/m2) | - | 31 ± 5.7 | 40.6 ± 5.7 * |

| CO-index (cc/m2) | - | 2425 ± 475 | 2788 ± 663 * |

| IL-1β (pg/ml) | 0.9 ±0.6 | 2.1 ± 3.1 | 3.1 ± 5.2 |

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | 2.5 ± 1.5 | 7.3 ± 10.1 | 9.6 ± 11.0 |

| Medication use, No. (%) of subjects | |||

| Metformin | 0 | 4 (16.7) | |

| Statins | 1 (4.7) | 2 (8.3) | |

| ARB | 0 | 4 (16.7) | |

| CCB | 0 | 2 (8.3) | |

| Β-blockers | 0 | 4 (16.7) | |

| Aspirin | 0 | 3 (12.5) | |

| Other NSAIDs | 0 | 4 (16.7) | |

| Antidepressants | 0 | 1 (4.2) | |

| PPI | 1 (4.7) | 4 (16.7) | |

| OCP | 2 (9.5) | 2 (8.3) | |

| CYP450 | Control group genotype (%) | Obese patient's genotype (%) |

|---|---|---|

| CYP1A2 | Ex (100) | Ex (100) |

| CYP2B6 | Ex (100) | Ex (95.7)- Ra (4.3) |

| CYP2C9 | IM (26.3)- Ex (73.7) | IM (27.3)- Ex (72.7) |

| CYP2C19 | IM (21.1)- Ex (36.8)- UR (42.1) | IM (27.3)- Ex (31.8)- UR (40.9) |

| CYP2D6 | IM (31.6)- Ex (36.8)- UR (31.6) | IM (40)- Ex (60) |

| CYP3A | PM (21.1)- IM (68.4)- Ex (10.5) | PM (13.6)- IM (72.7)- Ex (13.6) |

| Isoform | Phenotypic parameter** | Control group (C)* | Obese- BS* | Obese- AS* | p-value C vs. BS |

p-value C vs. AS |

p-value BS vs. AS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP1A2 | C2 h paraxanthine/ C2 h caffeine | 0.129 ± 0.073 | 0.166 ± 0.145 | 0.341 ± 0.396 | 0.31 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| CYP2B6 | C3 h OH-bupropion/ C3 h bupropion | 2.855 ± 0.988 | 3.954 ± 2.257 | 5.969 ± 3.703 | 0.05 | 0.001 | 0.01 |

| CYP2C9 | C3 h OH-flurbiprofen/ C3 h flurbiprofen | 0.074 ± 0.019 | 0.092 ± 0.043 | 0.110 ± 0.047 | 0.08 | 0.000001 | 0.01 |

| CYP2C19 | C3 h OH-omeprazole/ C3 h omeprazole | 0.686 ± 0.558 | 1.683 ± 2.767 | 1.887 ± 2.003 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.56 |

| CYP2D6 | C3 h dextrorphan/ C3 h dextromethorphan | 1.242 ± 0.835 | 1.091 ± 1.082 | 1.761 ± 1.592 | 0.65 | 0.22 | 0.15 |

| CYP3A4/5 | C2 h OH-midazolam/ C2 h midazolam | 0.633 ± 0.253 | 0.419 ± 0.257 | 1.000 ± 0.590 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00003 |

| Pump | Phenotypic parameter# | Control group (C) | Obese- BS* | Obese- AS* | p-value C vs. BS |

p-value C vs. AS |

p-value BS vs. AS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-gp | AUC0-3 fexofenadine | 248 ± 91 | 99.9 ± 98.7 | 143.1±174.4 | 5.1E-06 | 0.02 | 0.18 |

|

| 1 | Pregnane X Receptor |

| 2 | Constitutive Androstane Receptor |

| 3 | Aryl hydrocarbon Receptor |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).