Preprint

Case Report

A Rare Case of Cervical Cancer Metastasis to the Heart

Altmetrics

Downloads

143

Views

51

Comments

0

This version is not peer-reviewed

Submitted:

25 May 2023

Posted:

31 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Alerts

Abstract

Abstract Background: Most cardiac metastases emerge from primary lung, breast, and hematologic malignancies. The clinical manifestations of cardiac metastasis vary depending on tumor location and size. Cardiac metastasis from cervical squamous cell carcinoma is extremely rare and is mostly found on autopsy. We report a case of cervical cancer metastasis to the interventricular septum. Case Summary. This report discusses the case of a 48-year-old woman with interventricular septal metastases, originating from squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix. The woman came to our hospital after experiencing a fainting spell. Her hospital stay was notable for a brief syncopal event during a 30-second asystole episode, which ended spontaneously. Upon awakening, she reported severe chest pain. In response, she was quickly taken to the catheterization laboratory. There, a coronary angiography revealed an 80% blockage in her left anterior descending artery. Two years prior, our patient was diagnosed with invasive squamous cell cervical carcinoma with PET/CT showing no evidence of metastatic disease. A repeat PET/CT scan was done following cardiac catheterization and was significant for a mass along the interventricular septum of the heart. Discussion. Cardiac metastasis from primary cervical squamous cell carcinomas is scarcely reported in medical literature. Among these rare cases, the majority involved the right ventricle, with only three involving the left ventricle. There are no documented instances of metastasis to the interventricular septum. To our knowledge, this would be the first such case.

Keywords:

Subject: Medicine and Pharmacology - Cardiac and Cardiovascular Systems

Introduction

Cardiac metastases represent an exceedingly rare clinical entity, often diagnosed post-mortem. As per current literature, fewer than 12 live cases of cervical metastasis to the heart have been reported.1 With improvements in oncological therapies and associated survival benefits, the incidence of cardiac metastasis may increase. The majority of cardiac metastases emerge from primary lung cancer (36-39%), breast cancer (10%), and hematologic malignancies (10-20%).2 The rarity of cardiac metastasis is generally attributed to continuous myocardial contractions and variable blood flow during resting and stressed states, which together are hypothesized to hinder tumor cell adherence to the underlying cardiac tissue.3 Notably, cardiac metastasis stemming from cervical squamous cell carcinoma is extraordinarily rare, often only detected during post-mortem examination.2 The usual metastatic routes for cervical cancer encompass the lungs, liver, bones, and lymph nodes.4

History of presentation

A 48-year-old woman with a recent diagnosis of invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix presented to our hospital following a syncopal episode. Upon examination, she appeared comfortable with normal vital signs and no indication of orthostatic hypotension. There were no discernible signs of congestive heart failure or detectable murmurs upon cardiac auscultation. In comparison to prior, her ECG now showed a new left bundle branch block (Figure 1). Her laboratory workup revealed mildly elevated troponin I at 0.141 ng/ml, prompting her admission for observation and further diagnostic exploration.

Two years prior to her presentation at our facility, the patient had been diagnosed with invasive squamous cell cervical carcinoma. Initial staging at the time of diagnosis, based on PET/CT findings, revealed no metastatic disease, culminating in a FIGO stage IIB (p16+) classification. Subsequent treatment involved chemoradiation with six cycles of weekly cisplatin therapy. A follow-up PET/CT scan indicated a complete metabolic response to therapy, with no evidence of distant metastases.

During her hospitalization, her telemetry demonstrated brief asystolic episodes, symptomatic bradycardia, heart block, and atrial tachycardia. The hospital stay was marked by an episode of syncope during a 30-second asystolic event, which resolved spontaneously. Upon regaining consciousness, the patient reported severe chest pain.

She was promptly transferred to the catheterization laboratory, where coronary angiography demonstrated a right-dominant circulation with no significant disease in the left main, circumflex, and right coronary artery. However, an 80% obstruction was detected in the mid-left anterior descending artery (LAD), unresponsive to nitroglycerin (Figure 2A,B). Given the patient’s acute presentation and recurrent asystolic episodes during the procedure, intravascular coronary imaging was not performed. The patient experienced several additional asystolic arrests during angiography, prompting the placement of a permanent pacemaker due to her otherwise normal functional status.

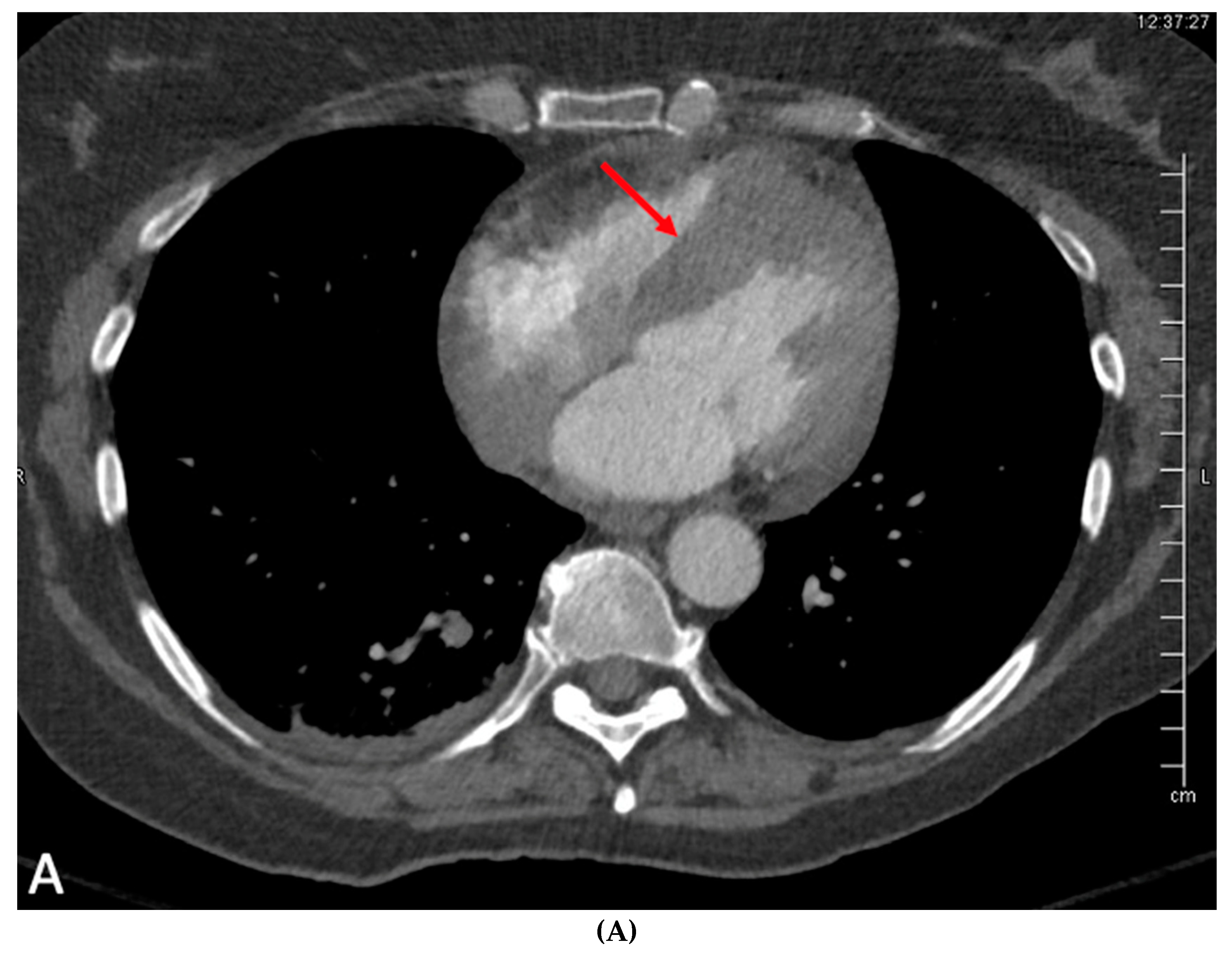

The angiographic findings suggested external compression as the likely cause of the 80% lesion in the mid LAD. This assumption gained credence when considering the non-invasive imaging results. Transthoracic echocardiogram showed normal left ventricular chamber diameter and systolic function with an ejection fraction of 50-55%, but was significant for notable septal wall thickening (Figure 3A–C). A subsequent PET/CT scan demonstrated an FDG-avid focus aligning with a heterogeneously enhancing mass along the interventricular septum of the heart, measuring approximately 3.1 x 2.8 cm, representing a significant change from her previous scan (Figure 4A,B). A post-procedural CT scan, performed after the emergent coronary angiogram and pacemaker implantation, revealed significant interventricular septal thickening corresponding to myocardial metastases (Figure 5A), a contrast to a CT performed approximately five months prior, which indicated normal septal thickness (Figure 5B).

The patient’s hospital course was uncomplicated, and she was discharged without further issues. Follow-up ECGs displayed ventricular pacing and underlying sinus tachycardia or atrial flutter with complete atrio-ventricular (AV) block, presumed to be a consequence of AV node infiltration by the metastasis in the interventricular septum. She was followed up in oncology and was continued on paclitaxel/topotecan and bevacizumab.

Several months later, the patient returned to the hospital complaining of chest pain. Given her overall prognosis, her symptoms were managed medically and she was subsequently discharged. Unfortunately, she later presented after suffering an out-of-hospital ventricular fibrillation cardiac arrest. Given the circumstances, the decision was made to transition her to comfort care, where she passed peacefully.

Discussion

The vast majority, up to 80% of cardiac metastases occur within the right-sided chambers of the heart.5 This tendency for right-sided metastases is thought to be due to the filtering role of the pulmonary circulation and the slower rate of blood flow through the right heart increasing hematogenous seeding. Of the few reported cases of cervical cardiac metastasis, three cases demonstrated left ventricular involvement but none of the reported cases demonstrated septal involvement which was seen in our patient.1

The clinical manifestations of cardiac metastasis vary depending on tumor location and size. Symptoms can range from chest pain, fatigue, weight loss, congestive heart failure from intracardiac obstruction, valvular pathologies, and features of pericardial effusion, while most common presentations are symptoms of heart failure, chest pain, and palpitations.6,7 While arrhythmias and conduction blocks have been reported with cardiac metastasis, they are exceedingly rare.8

The management of cardiac metastatic lesions originating from cervical carcinoma is notably challenging. In the literature, there is a solitary report detailing the surgical resection of a tumor situated in the right ventricle and pulmonary artery. Despite initial resection, the female patient experienced a recurrence of the right ventricular tumor within four months and subsequently succumbed to heart failure.9 Treatment options for patients grappling with cardiac metastases remain limited, often necessitating prioritization of palliative care. The median age at diagnosis for cervical cardiac metastasis is 49 years, with most patients presenting with stage II cancer or beyond. Unfortunately, the prognosis in all reported cases has been unfavorable, with the span of survival ranging from one to thirteen months, averaging approximately six months post-diagnosis.10

Despite this grim prognosis and compromised quality of life, personalized care decisions, potentially involving palliative therapies or the undertaking of procedures such as pacemaker implantation, can be navigated through a shared decision-making process. This underscores the importance of the clinician-patient relationship in managing these complex cases.

Funding

No specific funding was received for this work

Conflicts of Interest

None declared

References

- Kapoor K, Evans MC, Shkullaku M, Schillinger R, White CS, Roque DM. Biventricular metastatic invasion from cervical squamous cell carcinoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2016, 1;2016, :bcr2016214931.

- Bussani R, De-Giorgio F, Abbate A, Silvestri F. Cardiac metastases. J Clin Pathol. 2007, 60, 27–34.

- Jann H, Wertenbruch T, Pape U, Ozcelik C, Denecke T, Mehl S, et al. A matter of the heart: myocardial metastases in neuroendocrine tumors. Horm Metab Res Horm Stoffwechselforschung Horm Metab. 2010, 42, 967–976. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim HS, Park N-H, Kang S-B. Rare metastases of recurrent cervical cancer to the pericardium and abdominal muscle. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008, 278, 479–482. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam KY, Dickens P, Chan AC. Tumors of the heart. A 20-year experience with a review of 12,485 consecutive autopsies. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1993, 117, 1027–1031.

- Goldberg AD, Blankstein R, Padera RF. Tumors metastatic to the heart. Circulation 2013, 15;128, 1790–1794.

- Byun SW, Park ST, Ki EY, Song H, Hong SH, Park JS. Intracardiac metastasis from known cervical cancer: a case report and literature review. World J Surg Oncol. 2013, 11, 107. [CrossRef]

- Andrianto A, Mulia EPB, Suwanto D, Rachmi DA, Yogiarto M. Case Report: Complete heart block as a manifestation of cardiac metastasis of oral cancer. F1000Research 2020, 9, 1243. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, WC. Primary and secondary neoplasms of the heart. Am J Cardiol. 1997, 80, 671–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasidharan A, Hande V, Mahantshetty U, Shrivastava SK. Cardiac metastasis in cervical cancer. BJR Case Rep. 2016, 2, 20150300.

Figure 1.

ECG showing sinus rhythm with left bundle branch block.

Figure 2.

A: Coronary angiography in left anterior oblique cranial orientation with significant 80% obstruction of the mid left anterior descending artery (arrow). B: Coronary angiography in the right anterior oblique cranial orientation with the same significant ~80% obstruction in the mid left anterior descending artery (white arrow).

Figure 2.

A: Coronary angiography in left anterior oblique cranial orientation with significant 80% obstruction of the mid left anterior descending artery (arrow). B: Coronary angiography in the right anterior oblique cranial orientation with the same significant ~80% obstruction in the mid left anterior descending artery (white arrow).

Figure 3.

A: Transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) in parasternal long axis with left ventricle (LV) and left atrium (LA) for orientation, severely thickened interventricular septum (*) appreciated. B: TTE in the parasternal short axis with ultrasound contrast. Left ventricle (LV) with severely thickened anterior septum (*). C: TTE again in parasternal long axis with ultrasound contrast. Left ventricle visible (LV) for orientation and significantly thickened septum (*).

Figure 3.

A: Transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) in parasternal long axis with left ventricle (LV) and left atrium (LA) for orientation, severely thickened interventricular septum (*) appreciated. B: TTE in the parasternal short axis with ultrasound contrast. Left ventricle (LV) with severely thickened anterior septum (*). C: TTE again in parasternal long axis with ultrasound contrast. Left ventricle visible (LV) for orientation and significantly thickened septum (*).

Figure 4.

A: Positron emission tomography with fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake in the interventricular septum (red arrow) consistent with metastases from known cervical cancer, correlating with TTE findings above. B: Prior PET (3-4 months prior).

Figure 4.

A: Positron emission tomography with fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake in the interventricular septum (red arrow) consistent with metastases from known cervical cancer, correlating with TTE findings above. B: Prior PET (3-4 months prior).

Figure 5.

A: CT scan performed on index admission: significant interventricular septal thickening (red arrow) corresponding with metastases correlating with echocardiogram and PET/CT, performed a few weeks prior to admission. B: Compared to prior CT done approximately 5 months prior with normal appearing thickness of interventricular septum (blue arrow).

Figure 5.

A: CT scan performed on index admission: significant interventricular septal thickening (red arrow) corresponding with metastases correlating with echocardiogram and PET/CT, performed a few weeks prior to admission. B: Compared to prior CT done approximately 5 months prior with normal appearing thickness of interventricular septum (blue arrow).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Copyright: This open access article is published under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license, which permit the free download, distribution, and reuse, provided that the author and preprint are cited in any reuse.

MDPI Initiatives

Important Links

© 2024 MDPI (Basel, Switzerland) unless otherwise stated