1. Introduction

The development of communicative and linguistic skills, linked to oral language, reading or writing, is essential in higher education contexts. Their value lies not only in the opportunity they offer to demonstrate knowledge constructed at the university, but also because they are very powerful psychological instruments that make it possible to generate and transform knowledge, optimize learning or develop reflective thinking, among other factors [

1,

2,

3].

Oral language competence (OLC) [

4,

5] has implications at a personal, professional and social level, so its teaching and learning must be a priority, in line with what is established by the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages, proposed by the Council of Europe [

6].

Competence in oral language means that a person can construct complex, coherent, cohesive oral texts that are adapted to the context. At the same time, it implies the ability to request information, argue, ask for clarification, refute and reflect on their own language, among other skills, with different interlocutors and aims [

7].

This is important for all university students. It is especially relevant for students who are preparing to work as teachers, since they must help their future pupils to develop these competences and be a model of social interaction and language for them [

8]. OLC will be useful for them to enrich their own professional practice when they participate in activities as relevant as meetings with other teachers from the school, meetings with other professionals (such as educational psychologists and speech therapists) from the school or other services, with professionals linked to community services (social workers, representatives of education authorities, etc.) and with their pupils’ families.

For this reason, it is essential that university teachers work on OLC in an explicit, systematic way in the subjects of ITE. However, previous research shows that this is not always the case [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13] and that the design of subjects does not explicitly contemplate OLC or, when it does, it does not suppose more than one activity within the set of contents of the subject, which shows the lack of attention paid to it.

Research focused on the analysis of how teachers promote the development of OLC in ITE indicates that OLC is generally worked on in a non-systematic way or combined with written competence [

12,

14], which is what has traditionally been prioritized in formal education contexts. Likewise, it is observed that the activities that are carried out most frequently in university classrooms, linked to oral language, are associated with oral presentations or debates to promote critical thinking. The objectives linked to oral expression or the criteria that will be applied to evaluate the OLC are only defined occasionally [

17,

18].

The results of a study carried out with first year ITE students are especially relevant. In this study, students’ performance on the same content was compared, depending on whether it was expressed orally or in writing [

19]. The results show that almost a quarter of the students failed the contents of the subject when they were presented orally, while these same students passed the contents when they wrote them down. Only just over a tenth failed both tests (oral and written). The rest of the students did not show sufficient oral competence to verbally demonstrate understanding of the content worked on in the classroom.

Results shows that university ITE students feel that they do not have enough communication skills to communicate effectively in different situations (in class, in meetings or in meetings with a mentor), although these skills improve throughout their university studies. Furthermore, very few subjects explain the OLC objectives clearly or define the way in which contents related to OLC will be worked on and evaluated [

20,

21]. Another study highlights that 78% of ITE students expressed the need to incorporate a specific subject in the ITE aimed at developing this competence [

10]. Similarly, recent ITE graduates stated that they had not received sufficient training in this area and expressed the need to continue learning after graduation to be able to help their pupils to develop OLC in the school context [

8,

10,

11,

21].

The situations referred to above seem consistent with the fact that university teachers state that they are not sufficiently prepared or competent to help future teachers in the area of OLC. Despite being aware that this is a cross-cutting, interdisciplinary competence included in ITE plans, they do not systematically design programmes that include theoretical or methodological elements to promote this competence in ITE students [

23,

24].

Other reasons for the lack of explicit teaching of oral language in university contexts may be related to the belief that oral competence develops naturally, without the need for explicit teaching, or the fact that it is considered a competence that must be acquired in previous educational levels [

20].

A study carried out in Catalan universities [

18] shows that OLC can be developed, and students’ critical thinking encouraged by introducing in university classrooms content linked with conversational methodology. In this methodology, teaching is conceived as a participatory, active activity, where contents and ideas are questioned and the reviewed knowledge is jointly argued, counterargued and discussed [

25,

26,

27].

Specific strategies to encourage students to learn by speaking and learn to speak are identified by some authors [

28,

29]. They include: facilitating situations in which students discuss the contents worked on in the subjects, either in a small or whole group; offering opportunities for students to become aware of aspects related to oral language, such as the way they express themselves, the content of their oral production, the structure and organization of the discourse and the way they manage the conversation in different communicative situations; and encouraging reflection on the language and on one’s own linguistic competence and metatalk. These strategies are not just linked to a specific subject, for example in the language area. Instead, they must be considered in the set of subjects, since they are associated with a cross-cutting competence (OLC), which can be taught and learnt in the different knowledge areas [

30,

31,

32].

The presence of these strategies in ITE university classrooms and in the training of graduates in various disciplines (such as history, chemistry and linguistics) who want to be secondary education teachers (e.g. the Master’s degree in Secondary Education, MSE) [

33] depends on several factors. These include the profile of university teachers in terms of years of teaching experience, the type of relationship with the university (full time or part time) or the initial degree (for example, in psychology, linguistics, pedagogy, sociology, history, chemistry and mathematics). It may also be related to aspects such as the number of students in the classroom, the subject taught, the teaching methodologies used, or the resources that are invested and that directly affect these aspects, which should also be considered.

In this context, and within the framework of the ITE and the MSE, the study proposes the following objectives:

Analyze activities to promote OLC development that are carried out in university classrooms and their evaluation.

Explore teachers’ ideas on how to improve the development of their students’ OLC could be improved.

Analyze the relationship between students’ awareness of OLC work and activities to promote it.

Explore the relationship between teachers’ evaluation of their strategies to promote OLC, teachers’ perception of their students’ OLC and students’ OLC evaluation.

2. Materials and Methods

Participants

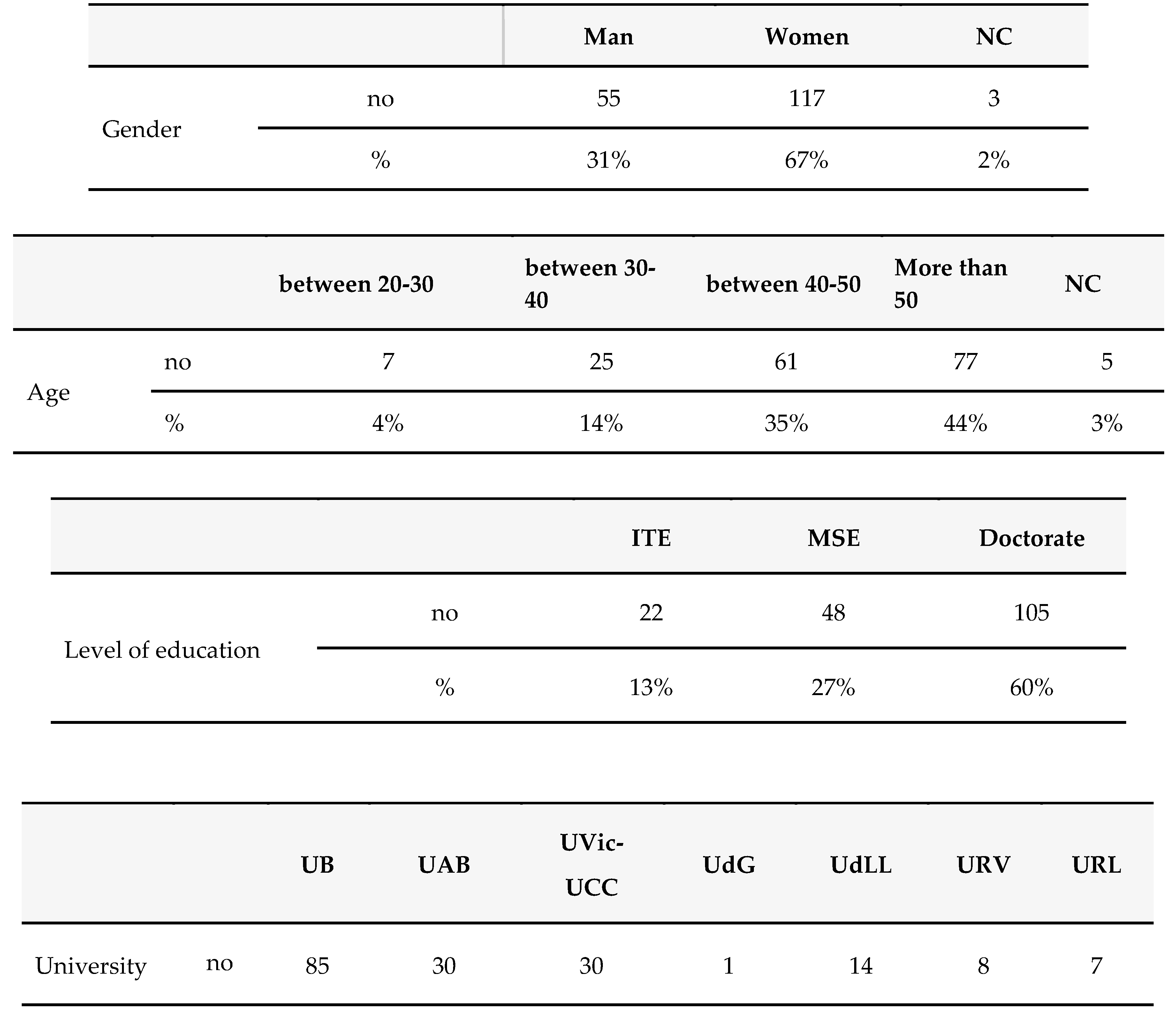

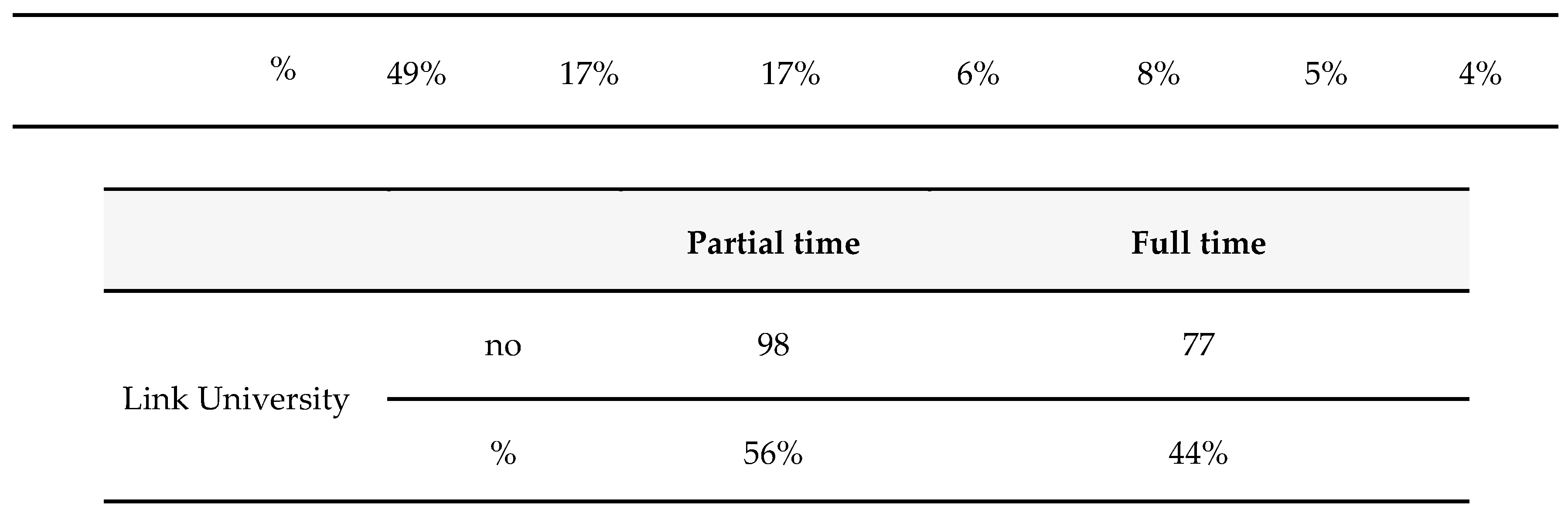

A total of 175 teachers participated who teach subjects in ITE (Early Childhood and Primary Education) (n=141) and in MSE (n=34) in 7 Catalan universities.

Table 1 shows the main characteristics of the participants.

Instrument

The main data collection instrument is an online questionnaire with 69 questions (Appendix A). At the beginning of the questionnaire, informed consent was requested from the participants. Of the 69 questions, the initial section consists of 15 questions, 9 single-answer closed questions and 6 open-ended questions, designed to determine the teacher’s profile. The rest of the questions in the instrument are organized into 6 thematic sections: 1) Activities to work on OLC, 2) Strategies to work on OLC, 3) Assessment of OLC (which dimensions are more relevant), 4) Evaluation of OLC (which dimensions teachers evaluate), 5) Improvement of OLC and 6) Improvement of teachers’ strategies and skills to contribute to the development of students’ OLC.

The first section includes 6 questions focused on determining how the teachers work on OLC in the classroom and the type of activities that are done. This section consists of a series of multiple-choice questions and an open question so that the teacher can express more specifically what type of activities they work on that have not been mentioned in the multiple-choice options. This section includes questions related to the teachers’ perceptions of students’ awareness of the use of oral language and what they do to improve it. To achieve this, two multiple-choice questions are included, followed by an open question.

The second section includes four questions whose objective is to find out how teachers’ evaluate the strategies they use to help their students develop OLC, how often they use these strategies, and the consciousness they have of themselves as models for their students.

The third section has six questions that aim to find out which dimensions of OLC (pragmatics, lexicon, vocabulary, discursive strategies, comprehension, form and non-verbal communication) are more relevant for teachers, and the dimensions that they believe their students need to develop further. Two of the questions in this section are multiple choice, one is a dichotomous question and two open questions.

The fourth section includes 27 questions and its purpose is to determine whether teachers evaluate the OLC, which dimensions they evaluate and with what instruments, when they undertake the evaluation and how often. Of the 27 questions, five are dichotomous, 11 multiple choice and 11 are open-ended questions that are mostly derived from the multiple-choice questions.

The fifth section includes seven questions to explore the elements that the teacher could change and improve with respect to work on OLC in their subject. To achieve this, one dichotomous question, three multiple choice questions and three open questions are included.

Finally, the sixth section consists of four questions to find out strategies to improve teaching skills and possible agents to contribute to better development of students’ OLC. Two of the questions are multiple choice, and another open-ended question was derived from each one.

Procedure

The questionnaire was prepared by three of the team’s researchers based on the six sections described above, refined by various readings and reviews. The first version of the instrument was sent to 6 teachers from different Catalan universities who reviewed the questions based on their experience as ITE and MSE teachers. The comments and suggestions for change were discussed by the researchers and the instrument was adjusted. After that, four ITE teachers from one of the participating universities answered the questionnaire, and the experience was evaluated with them. The last adjustments were made and the version was considered ready to be validated.

A message was written and sent by email to the directors of ITE studies at the 7 universities with information about the project, along with a link to the questionnaire, and a request for them to send the questionnaire to all ITE teachers. In addition, the list of MSE teachers from the 7 universities was reviewed on the corresponding webpages, and the same email message with the link was sent directly to all the teachers. In cases in which the list of teachers was not public, the programme directors were contacted so that they were the ones to send the message via email to the teachers, just as the directors of ITE had done.

In the message, teachers were asked to answer within a maximum period of one month. Once this time had elapsed, as it was considered that there were insufficient responses (140), the same message was sent again to the ITE and MSE coordinators, and to the MSE teachers of the 7 universities, to remind them of the researchers’ interest in learning about their experience. New responses were obtained, until the number of 175 was reached, which was considered sufficient.

Data Analysis

For the data analysis, firstly the descriptive statistics of the sample were calculated to explore the variables in relation to the training and professional context of the teachers and the work on OLC that they carried out in their subjects. Additionally, Pearson’s chi-squared tests and Spearman’s correlations were carried out with a confidence level of 95% to explore the relationships between the variables analysed, especially the relationships between the specific activities to work on OLC, its evaluation or not in the subject, the teachers’ perceptions of their students’ level of competence and the students’ awareness of OLC work in the classroom. The SPSS version 26 program was used for the data processing.

3. Results

3.1. Activities to Promote the Development of OLC that Are Carried Out in University Classrooms and Their Evaluation

Table 2 shows that 92.57% of the teachers stated that they work on OLC indirectly, along with other competences and contents of the subject, while 76.57% propose activities that are specifically linked to OLC. Full-time teachers stated more frequently than part-time teachers that they totally disagreed with proposing activities specifically related to OLC (Pearson’s chi-squared, p= .029).

Table 3 shows the response trend of teachers in relation to the type of strategies they use to help and accompany students in the OLC development process. They were asked to indicate the degree of agreement with each of the statements using four response options (0=never; 1=sometimes; 2=often; 3=always). The strategy they used most frequently was to make it easier for students to ask questions (x=2.84), followed by making it easier for students to give their opinions and answers (x=2.75) and making it easier for students to express their opinions (x=2.75). The strategy that teachers only used sometimes was to help students to become aware of the importance of using new vocabulary when they make contributions in class (x=1.93), or to help them to discuss topics in a group in class (x=2.07).

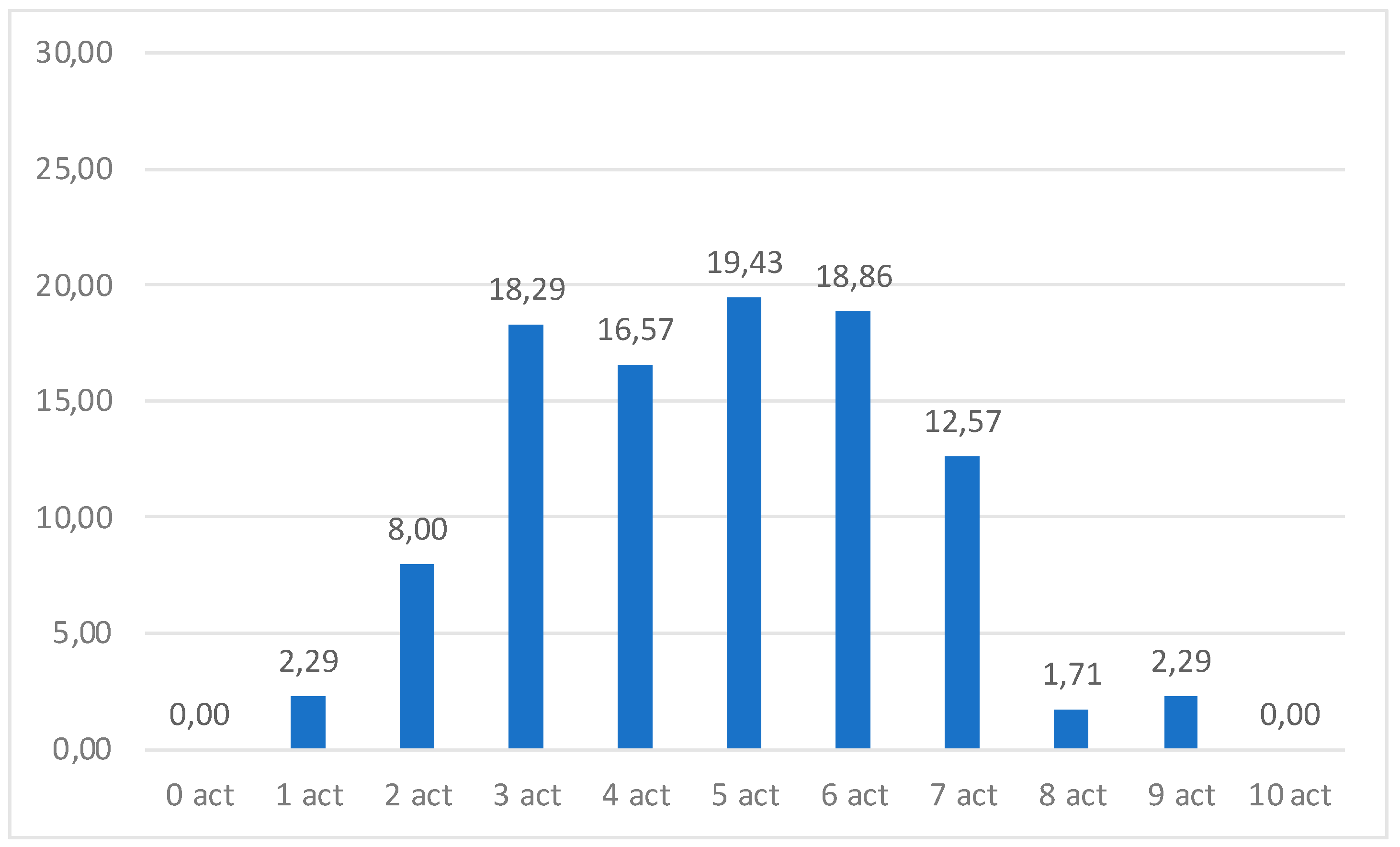

As shown in

Figure 1, most of the teachers stated that they carry out between 2 and 7 activities on OLC throughout the semester, with an average of 4.72 activities. Among the activities on OLC, the most mentioned (see

Table 4) were the promotion of student participation in the sessions through questions, contributions or reflections (87.43%), oral presentations (77.14%), discussions with the class group (72%), in small groups (63.43%) or debates (66.29%). The least used were audio recorded oral activities (12%) or interviews (14.29%).

Some significant differences were found in the type of activities that are promoted. The results indicate that ITE teachers make more oral presentations than MSE teachers (p= .003). In addition, some statistically significant differences were found between years of teaching experience and oral activities recorded on video. Teachers with 5 to 10 years of experience used oral activities recorded on video more than other teachers. Teachers with over 10 years of experience stated that they used such activities to a lesser extent than the rest of the teachers (p= .015).

In the question, Do you think the students are aware that you are working on OLC in your subject?, differences were detected in the option “quite” between part-time and full-time teachers (p= .031), with part-time teachers choosing this option much more frequently than full-time teachers.

As shown in

Table 5, 65.14% of the participants answered that they evaluate OLC in their subject, while 34.86% indicated that they do not.

Table 5 shows the frequency and percentages of each dimension.

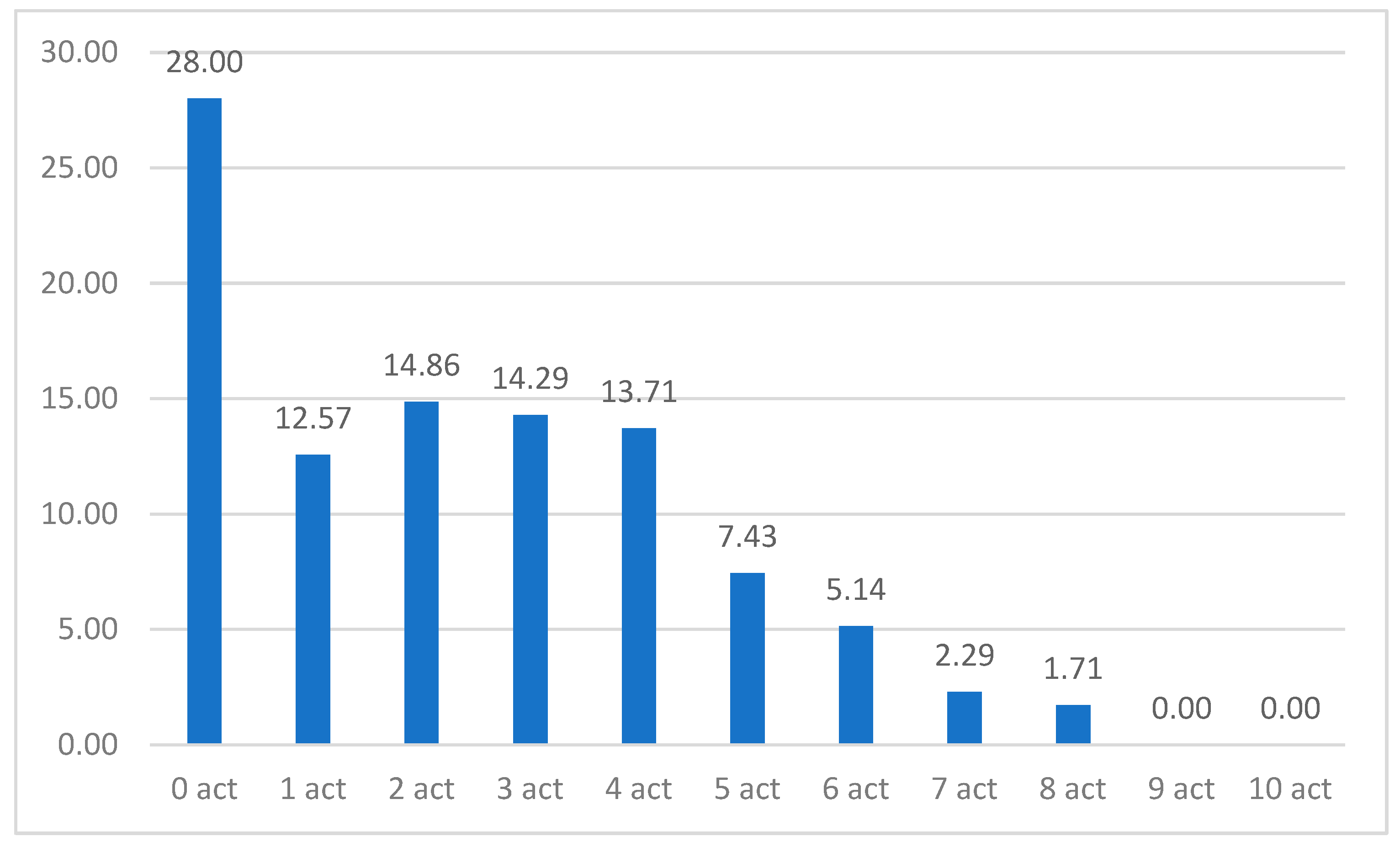

Among the teachers who evaluate OLC, the average is 2.38 activities during the semester (see

Figure 2). The most frequently mentioned activities (see

Table 6) were the oral presentation (65.1%), contributions of students during lessons (31.4%), debates (29.7%), discussions about the contents that are worked on (27.4%) and oral activities recorded on video (27.4%). The least used activities to evaluate OLC were oral activities recorded on audio (8%) or interviews (9.14%).

As for the number of activities that they evaluate per semester, ITE teachers stated that they evaluated the OLC of their students through more than 3 semester activities, which is well above the number of activities used by MSE teachers (p= .028). In relation to the type of activities for OLC evaluation, ITE teachers used oral presentations (p= .022) and peer evaluation (p= .023) more frequently than MSE teachers. Likewise, ITE teachers reported more frequently that they share the evaluation criteria when they explain and give guidelines on the activities (p= .010).

Teachers with between 5 and 10 years of teaching experience in higher education evaluate OLC thoughout the activities and not only at the beggining or at the end, more than the rest of teachers. In contrast, most experienced teachers (more than 10 years) use the evaluation thoughout the activities less than other teachers (p= .036).

As regards the way in which teachers make the evaluation criteria known to students, teachers with between 5 and 10 years of experience stated more frequently than the rest of the teachers that they make the evaluation criteria known orally. The trend was different for teachers with more than 10 years of experience, who reported that they communicate little orally about the evaluation criteria compared to the rest of the teachers (p = .018).

Finally, ITE teachers share evaluation criteria with students significantly more frequently than MSE teachers (p= .015). The same results were obtained in relation to making students aware of working on OLC by offering them specific feedback. ITE teachers offered OLC feedback to their students significantly more frequently than MSE teachers (p= .003).

3.2. Teachers' Ideas on How to Improve the OLC of Their Students

The results show that 82.3% of the teachers considered that they could do more to promote their students’ OLC. Regarding the question, How do you think you can improve the OLC of your students in your subject?, 39.4% reported that this change depends on the possibility of carrying out more discussions on the contents that are worked on, 37.1% considered that the number of oral presentations could be increased, 34.9% considered that students have to participate more in class, 32% indicated that debates in the classroom should be increased, 28.6% believed that it is necessary to increase activities on video, and 25.1% chose to increase discussions in small groups.

Regarding the question, Do you think you could do more to promote the OLC of your students?, teachers of language subjects (19%) answered more frequently than teachers of non-language areas that there was little else they could do to promote the OLC of their students (p= .029). Language teachers were less likely to select some response options that the other teachers found useful, for example, Someone who observes my classes and helps me evaluate them (p= .002) or Discuss with the coordinators and teachers of the subject and make decisions to introduce changes (p= .037).

Among the options offered to teachers as suggestions for change, 50.9% of teachers thought that to improve the students’ OLC, the student-teacher ratio in the classroom must be reduced, 36.6% considered that changes should be coordinated and introduced in the course plans, 34.9% believed that it would be beneficial to observe good teaching models and 34.9% affirmed that teachers’ competence needs to be improved. A total of 85.1% of teachers considered that improving students’ OLC is not only the responsibility of language subjects but is a general responsibility of all subjects. Statistically significant differences were found between the ITE and MSE teachers on reducing the student-teacher ratio per classroom (p= .008) as a way of improving students’ OLC. MSE teachers, who have smaller groups, did not consider this option as a proposal for improvement, unlike ITE teachers. Likewise, ITE teachers were more likely to consider that to improve OLC, students must participate more in class (p= .010).

Teachers with fewer years of teaching experience (1 to 5 years) were more likely than teachers with over 10 years of teaching experience to consider that students’ OLC can be improved by facilitating their contributions (p= .004).

When teachers reflected on aspects to improve in terms of their own teaching strategies to contribute to the development of students’ OLC, they selected the options of improving their strategies to promote student participation in class (56.6%), improving strategies to evaluate students’ oral contributions (53.1%) and designing evaluation instruments (44.6%). A total of 42.3% of teachers considered that it is necessary to improve communication between the subject’s teaching team, develop networking (30.9%) and improve teachers training (29.1%). Regarding which entity would be responsible for helping teachers to improve their skills to promote students’ OLC, 49.7% considered that departments in the language area are responsible, 28.6% considered that the Faculty of Education is responsible, 25.1% thought that it was a task for the coordination of the subject, and 22.9% opted for the Professional Development Institute (IDP).

3.3. Relationship between Students' Awareness of OLC Work and Class Activities

Chi-squared tests and Spearman correlations were carried out to explore the possible relationships between the activities to promote OLC proposed by the teachers, their evaluation proposals, and students’ awareness of OLC promotion, as perceived by the university teachers in their subjects.

A significant positive correlation was observed between students’ degree of awareness of OLC promotion and specific activities to promote this competence (Spearman’s Rho= .532, p> .001). Results showed a significant correlation between students’ awareness of working with OLC and teachers who implemented more specific activities to promote it. A moderate correlation between the role of teachers as a model of OLC and students’ awareness (Spearman’s Rho= .307, p> .001) was observed. Teachers who perceived greater students’ awareness of OLC work in their subjects also showed a greater degree of agreement with being a model of oral linguistic competence for their students.

A chi-squared analysis was conducted for each specific promotion activity. A significant relationship was found between awareness of OLC and debates (p= .035), video recorded activities (p= .025) and role playing and simulations (p= .042). This indicated a greater degree of awareness of students by the teachers who implemented these specific activities.

Some types of activities to develop OLC awareness showed a significant chi-squared relationship with students’ OLC awareness. The relationship was significant between OLC awareness and communicating the goals of OLC activities (p < 0.001), and specific feedback (p < 0.001). Teachers who implemented activities to promote awareness considered that students had a higher level of OLC awareness. Teachers who did not communicate evaluation criteria (p= .003), did not use self-evaluation (p = .007) and did not use co-evaluation (p = 0.002) to promote awareness of OLC work in the subject stated that students had low or very low awareness of OLC.

3.4. Relationship between Teachers' Evaluation of Their Strategies to Promote OLC, Students' OLC Performance and Students' OLC Evaluation

Regarding teachers’ self-evaluation of their strategies to promote students’ OLC development, Pearson’s chi-squared analysis showed that teachers who do not evaluate their students’ OLCs also had a lower opinion of their strategies to promote students’ OLCs and vice versa. Pearson’s chi-squared analysis results were significant for the evaluation for formal aspects of OLC (p> .001), the lexical dimension (p> .001), the pragmatic dimension (p= .001), the comprehension dimension (p= .005) and nonverbal communication (p = .001).

Pearson’s chi-squared analysis was conducted for students’ OLC awareness and the evaluation of these five dimensions of OLC. The results show that teachers who evaluated these dimensions also considered that their students had a good level of OLC awareness (see

Table 7). In contrast, teachers who stated that their students had a poor level of OLC awareness generally did not implement OLC evaluation activities.

Additionally, Pearson’s chi-squared analysis was conducted for each teacher’s specific strategy to promote OLC and each evaluation dimension of OLC. The results were significant only for the pragmatic dimension with discussion activities in small groups (p= .037) and whole class (p= .009). For the comprehension dimension, discussions in small group (p= .014) and whole class (p=.023) were also significant. That is, teachers focused their evaluation on the pragmatic and comprehension dimensions significantly only for these activities. An evaluation of the formal dimension of OLC showed a significant relationship with activities to promote vocabulary awareness (p= .043), and there was a significant relationship between this activity and the lexical dimension (p< .001). For this last dimension, the strategy of promoting the incorporation of new vocabulary in student participation was also significant (p= .004). Teachers tended to evaluate aspects related to the lexicon in specific activities for this purpose, and only evaluated the lexical dimension in a general way when students participated in class. The most significant dimension in relation to the strategies for promoting students’ OLC was the pragmatic dimension. The evaluation of this dimension was significant in relation to the awareness of the vocabulary used in class participation (p=.038) and for promoting the expression of students’ opinions (p= .048).

Finally, the Chi-squared analysis in relation to teachers’ awareness of their role as a OLC model for students showed significant results only for the lexical (p=.011) and pragmatic (p= .009) dimensions. The results showed that the teachers who were more likely to consider that they were OLC models for their students were those who specifically evaluated lexical and pragmatic dimensions during classroom activities.

4. Discussion

The results indicate that a high percentage of ITE and MSE teachers work on OLC in their subjects and propose activities specifically linked to OLC. These results do not coincide with others obtained in previous studies that highlighted the low presence of this type of activity in higher education [

18,

34,

35].

The most common strategies of teachers to contribute to the development of their students’ OLC were to make it easier for students to ask questions, to give their opinions and answers, and to express their opinions. Other strategies such as helping students to become aware of the importance of using new vocabulary when they contribute in class, or facilitating group discussions in class, were less common. Especially in the first case, these are strategies that promote reflection on language and on their own OLC, which is the first step to be able to improve it, as indicated by some studies on metalinguistic competences [

29,

30]. In relation to group discussions, it was found that in the university context there is a lack of methodologies that promote group work as a key element for the development of all competences and especially OLC. This was also found in previous studies [

36,

37,

38].

The most frequently mentioned activities for working on OLC are students’ participation in sessions through questions, contributions, or reflections; oral presentations; the proposal of class discussions in small groups; and debates. These results coincide with other studies that show that oral presentations are one of the most frequent activities to work on oral language [

15,

16]. However, some activities that were not frequently mentioned in this study are described in other studies, for example, discussions [

39]. We should explore in more detail what type of discussions take place and the degree to which teachers manage them so that they effectively promote the development of OLC in line with what some studies understand by conversational methodology [

10,

40] or dialogic teaching [

29,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45].

Notably, some activities that we consider very important for future teachers were only mentioned infrequently. These include oral activities recorded on audio and interviews. The former is relevant because, like some mentioned above, they mean giving importance to reflection on language, awareness of language or metalanguage [

30,

35,

38,

41]. The fact that a teacher asks students to record their oral output in audio format, even if it is only to analyze the more formal aspects of the language, such as the voice, already indicates a certain awareness of the importance of reflection on language. In another line are activities such as interviews. Teachers of various educational levels dedicate a considerable amount of their daily work to interviews or meetings with families and other professionals in the educational field, such as educational psychologists, speech therapists or social workers. For this reason, some skills are necessary that are not usually taught in ITE and should be taught, as various authors have pointed out [

41,

46,

47].

Regarding teachers’ evaluation of students’ OLC, pragmatics and discursive strategies are evaluated by only slightly more than half of the teachers, and less than half evaluate non-verbal communication. These are key OLC dimensions for a future teacher, not only for managing classes with their pupils, in which pragmatics and strategies are the basis of any teaching and learning process [

31,

40] but also for their effective participation in meetings with other teachers in the school, with families and with other professionals [

48].

The results showed that activities that involve the possibility of analyzing in detail the students’ output that are also likely to be evaluated by them, such as oral activities recorded on video, audio or interviews, are very infrequent. Once again, this leads us to consider the lack of importance that is given to the systematic analysis of oral output, both by teachers and students, as a key element of reflection on language [

49].

The results indicate that ITE teachers evaluate the OLC more frequently than MSE teachers through co-evaluation and that they share the evaluation criteria when they explain and give guidelines on the activities to be developed, which is positive. However, it would be necessary to deepen and find out in more detail what level of reflection is promoted in the classroom regarding the evaluation of classmates’ productions, and what type of items are included in the evaluation guidelines or rubrics with the students [

49]. Very often, these are very simple rubrics or templates that fundamentally evaluate formal aspects such as the speed of speech, body position or the volume of the voice, and do not include other aspects that are associated with the cohesion of the oral text, the ability to generate oral texts that are not memorized, the answer to other students’ questions, or the integration of gestures and facial expressions (multimodality) in oral texts [

50].

Regarding the results linked to the teachers’ answers on how to improve their students’ OLC, 39.4% report that change depends on the opportunity to have more discussions about the content in the classroom and 37.1% consider that the number of oral presentations should be increased. This seems to be an unclear result about what should be deepened, since oral presentations are a common activity, as indicated in previous paragraphs. It is illogical to consider that the way to improve students’ OLC is by doing more of what is already done. The result for classroom discussions coincides with what we have stated in previous works [

10], which coincides with the conclusions of other authors [

26,

51]. The participation of students in class discussions, if they can manage the activity in an increasingly autonomous way, introduce the vocabulary they are learning, argue their positions, reflect on the contents they are working on and on their own competence, is an activity that has enormous potential for working on the OLC of future teachers [

52,

53,

54].

Other activities indicated by the teachers are make it easier for students to participate more in class (34.9%), hold debates (32%), and carry out video activities (28.6%) or small group discussions (25.1%). All of them are essential activities to promote students’ OLC, although they should have been selected by a greater number of teachers, in our opinion. This indicates that university teaching staff are still not aware of how important it is for students to participate in class, not only to develop OLC, but also to learn the content that is worked on in a significant way. This is probably a sign that a conception of traditional university teachers remains, with the idea that they have to present the content (lectures) to transmit (not construct) knowledge for the students, who listen passively to their explanations [

14,

55].

Regarding other ways of promoting students’ OLC, the results indicate that teachers of language subjects choose less frequently than teachers of other subjects the possibility of having a person or colleague (another teacher) observe their classes and help them to assess students or discuss aspects with coordinators and other teachers of the subject and make decisions to introduce changes. This result reveals that teachers of language subjects consider that they do not need the opinions of other teachers about their classes, they feel very confident about what they do and they do not need to discuss what they do in class, even with other teachers of the same subjects. These perceptions are never good, but even less so if they come from language subject teachers. They probably once again indicate a very traditional conception of language that is far from pragmatic conceptions, which delve not so much into the knowledge of syntactic, orthographic rules and norms or those related to the correct pronunciation of the sounds of a language but rather the use that is made of the language, the effect this produces on others (children, families, etc.) and the strategies teachers need to learn to use to contribute to the development of their future pupils’ OLC [

35].

To end with the results linked to proposals to improve students’ OLC, some teachers consider that it would be beneficial to observe good teaching practices and that the development of communicative competence is not only the responsibility of language subjects. Instead, it is a responsibility transversal to all subjects, since it is interdisciplinary in nature, as previous studies have pointed out [

14,

56]. Teachers should be aware that observing other teachers is important and that it is necessary to continue learning.

OLC awareness results show that teachers who evaluate lexical, pragmatic, comprehension and nonverbal communication dimensions also consider that their students have a good level of OLC awareness. It seems that the perception of students’ awareness of the importance of OLC is linked to the evaluation of the dimensions in the classes, which probably activates this awareness, and promotes progress by the students. When class activities related to this competence are not carried out, the teachers themselves consider that the students do not have competences, in line with what other studies have highlighted [

57,

58,

59,

60]. These are relationships that are probably two-way in nature but together seem to indicate that if university teachers are not aware of the importance of OLC, activities are not proposed, they are not evaluated, students are not encouraged to become aware of the importance of OLC and are considered to have poor competence.

Regarding teachers’ self-evaluation of their strategies to promote students’ OLC development, the results show that teachers who do not evaluate OLC in their subjects also have a lower opinion of their strategies to promote students’ OLC and vice versa. These results coincide with those of previous studies that highlight foreign language university teachers’ awareness of their training needs to teach oral language to their students and motivate them in this area [

61]. In our case, we are dealing with teachers of different subjects and areas, some of whom probably have not participated in learning processes related to the teaching of oral language during their degree. However, this does not mean that they cannot learn them in other professional development contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G., and S.E.; methodology, M.G. and V.Q.; validation, M.G., F.V. and A. M.; formal analysis, M.G and I. M..; investigation, M.G., F.V., I. M., A.M. and V.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G.; writing—review and editing, M.G., F.V. and I.M..; visualisation, I.M..; project administration, M.G.; funding acquisition, M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.