Submitted:

30 May 2023

Posted:

01 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- -

- Does the sector in which organizations operate matter in terms of employees’ perceptions regarding their opportunity to use NWW in their organization?

- -

- Is the perceived opportunity to use NWW practices associated with institutional and organizational characteristics?

- -

- Do sectoral differences affect actors’ attributions of the intended objectives of NWW?

2. Theoretical backgrounds

3. Literature review and hypotheses

New Ways of Working

New Ways of Working across sectors: Lack of empirical evidence

Differences between sectors

4. Methods

Sample

- -

- Public sector organizations: Geneva cantonal administration; Vaud cantonal administration; Geneva city administration; Lausanne city administration; University of Lausanne.

- -

- Private sector organizations: Intuitive (SME active in the medical field); Loyco (SME active in business consulting); Vaudoise Assurance; Romande Energie.

- -

- Organizations from the semipublic sector (or public companies): Services Industriels Genevois (SIG); Loterie Romande.

Measures

Dependent variable

Independent variables

- (1)

- When researchers want to test a theoretical model from a predictive perspective.

- (2)

- When the structural model to be tested is complex and includes several variables, indicators, and relationships between variables.

- (3)

- When the research objective is to understand a phenomenon by exploring theoretical developments or extensions of already established theories.

- (4)

- When the statistical model includes formative variable (NWW variable in this research).

| Autonomy | Job goal clarity | Prod-attribution | Red tape | Sector | WB-attribution | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomy | |||||||

| Job goal clarity | 0.287 | ||||||

| Prod-attribution | 0.104 | 0.112 | |||||

| Red tape | 0.019 | 0.073 | 0.014 | ||||

| Sector | 0.110 | 0.027 | 0.104 | 0.072 | |||

| WB-attribution | 0.288 | 0.240 | 0.473 | 0.052 | 0.111 | ||

| Autonomy | Goal clarity | NWW | Prod-attribution | Red tape | Sector | WB-attribution | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomy | 1.144 | |||||||

| Job goal clarity | 1.110 | |||||||

| NWW | ||||||||

| Prod-attribution | 1.296 | |||||||

| Red tape | 1.014 | |||||||

| Sector | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.031 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| WB-attribution | 1.418 | |||||||

| Q²predict | RMSE | MAE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomy | 0.010 | 0.996 | 0.792 |

| Job goal clarity | -0.001 | 1.002 | 0.773 |

| NWW | 0.119 | 0.939 | 0.766 |

| Prod-attribution | 0.010 | 0.995 | 0.819 |

| Red tape | 0.005 | 0.999 | 0.804 |

| WB-attribution | 0.012 | 0.995 | 0.804 |

5. Results

6. Discussion

Limitations and future research

7. Conclusion

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nijp, H. H.; Beckers, D. G. J.; Van De Voorde, K.; Geurts, S. A. E.; Kompier, M. A. J. Effects of new ways of working on work hours and work location, health and job-related outcomes. Chronobiology International 2016, 33, 604–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ten Brummelhuis, L. L.; Bakker, A. B.; Hetland, J.; Keulemans, L. Do new ways of working foster work engagement? Psicothema 2012, 24, 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Renard, K.; Cornu, F.; Emery, Y.; Giauque, D. The Impact of New Ways of Working on Organizations and Employees: A Systematic Review of Literature. Administrative Sciences 2021, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, T.; Van De Voorde, K.; Paauwe, J. The effects of working agile on team performance and engagement. Team Performance Management: An International Journal 2022, 28, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knights, D.; Clarke, C. A. It’s a Bittersweet Symphony, this Life: Fragile Academic Selves and Insecure Identities at Work. Organization Studies 2014, 35, 335–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giauque, D.; Renard, K.; Cornu, F.; Emery, Y. Engagement, Exhaustion, and Perceived Performance of Public Employees Before and During the COVID-19 Crisis. Public Personnel Management 2022, 0, published online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerards, R.; Van Wetten, S.; Van Sambeek, C. New ways of working and intrapreneurial behaviour: the mediating role of transformational leadership and social interaction. Review of Managerial Science 2021, 15, 2075–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruud, G.; Andries, D. G.; Claudia, B. Do new ways of working increase work engagement? Personnel Review 2018, 47, 517–534. [Google Scholar]

- Cornu, F. New Ways of Working and Employee In-Role Performance in Swiss Public Administration. Merits 2022, 2, 146–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blahopoulou, J.; Ortiz-Bonnin, S.; Montañez-Juan, M.; Torrens Espinosa, G.; García-Buades, M. E. Telework satisfaction, wellbeing and performance in the digital era. Lessons learned during COVID-19 lockdown in Spain. Current Psychology 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, T. J.; Atwater, L. E.; Maneethai, D.; Madera, J. M. Supporting the productivity and wellbeing of remote workers: Lessons from COVID-19. Organizational Dynamics 2022, 51, 100869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marino, L.; Capone, V. Smart Working and Well-Being before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 2021, 11, 1516–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandl, J.; Kozica, A.; Pernkopf, K.; Schneider, A. Flexible Work Practices: Analysis from a Pragmatist Perspective. Historical Social Research / Historische Sozialforschung 2019, 44, 73–91. [Google Scholar]

- Wessels, C.; Schippers, M. C.; Stegmann, S.; Bakker, A. B.; Van Baalen, P. J.; Proper, K. I. Fostering Flexibility in the New World of Work: A Model of Time-Spatial Job Crafting. Frontiers in Psychology 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Jeong, S.; Chai, D. S. Remote e-Workers’ Psychological Well-being and Career Development in the Era of COVID-19: Challenges, Success Factors, and the Roles of HRD Professionals. Advances in Developing Human Resources 2021, 23, 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, R.; Kruyen, P. M.; Van Der Heijden, B. I. J. M.; Van Thiel, S. One HRM Fits All? A Meta-Analysis of the Effects of HRM Practices in the Public, Semipublic, and Private Sector. Review of Public Personnel Administration 2020, 40, 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borst, R. T.; Kruyen, P. M.; Lako, C. J.; De Vries, M. S. The Attitudinal, Behavioral, and Performance Outcomes of Work Engagement: A Comparative Meta-Analysis Across the Public, Semipublic, and Private Sector. Review of Public Personnel Administration 2020, 40, 613–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leede, J.; Kraijenbrink, J. The Mediating Role of Trust and Social Cohesion in the Effects of New Ways of Working: A Dutch Case Study. In Human Resource Management, Social Innovation and Technology; Bondarouk, T., OlivasLujan, M. R., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Ltd.: Bingley, 2014; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlmann, S.; Wollmann, H. Introduction to Comparative Public Administration; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham (UK)/Northampton, MA (USA), 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel, M. The Politics of Translation: How State-Level Political Relations Affect the Cross-National Travel of Management Ideas. Organization 2005, 12, 275–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, B. G. , Institutional theory in political science : the "New Institutionalism". Réimpr. ed.; Continuum: London etc, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, R. W. Institutions and Organizations. Ideas and Interests; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Finnemore, M. National Interests in International Society; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, W. W.; DiMaggio, P. J. The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis; Chicago University Press: Chicago, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, H. The Shared Challenges of Institutional Theories: Rational Choice, Historical Institutionalism, and Sociological Institutionalism; In Springer International Publishing, 2018; pp. 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- March, J. G. A Primer on Decision Making: How Decisions Happen; Free Press: New York, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, J. L.; Vandenabeele, W. Behavioral Dynamics: Institutions, Identities, and Self-Regulation. In Motivation in Public Management. The Call of Public Service; Perry, J. L.; Hondeghem, A., Eds. Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2008; pp. 56–79. [Google Scholar]

- Thoenig, J.-C., Institutional Theories and Public Institutions: Traditions and Appropriateness. In Handbook of Public Administration; Peters, B. G.; Pierre, J., Eds. SAGE: London, 2005.

- Hackman, J. R.; Oldham, G. R. Motivation Through the Design of Work: Test of a Theory. Organizational behavior and human performance 1976, 16, 250–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giauque, D.; Weissbrodt, R., Job design and public employee work motivation: towards an institutional reading. In Research Handbook on Motivation in Public Administration; Stazyk, E. C., Davis, R. S., Eds. Edward Elgar: Cheltenham (UK)/Northampton (USA), 2022; pp. 249–263.

- Knight, C.; Parker, S. K., How work redesign interventions affect performance: An evidence-based model from a systematic review. Human Relations 2021, 74, 69–104. [CrossRef]

- Chordiya, R.; Sabharwal, M.; Battaglio, R. P. Dispositional and organizational sources of job satisfaction: a cross-national study. Public Management Review 2019, 21, 1101–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishii, L. H.; Lepak, D. P.; Schneider, B. Employee Attributions of the “Why” of Hr Practices: Their Effects on Employee Attitudes and Behaviors, and Customer Satisfaction. Personnel Psychology 2008, 61, 503–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfes, K.; Veld, M.; Fürstenberg, N. The relationship between perceived high-performance work systems, combinations of human resource well-being and human resource performance attributions and engagement. Human Resource Management Journal 2021, 31, 729–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewett, R.; Shantz, A.; Mundy, J.; Alfes, K. Attribution theories in Human Resource Management research: a review and research agenda. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 2018, 29, 87–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Voorde, K.; Beijer, S. The role of employee HR attributions in the relationship between high-performance work systems and employee outcomes. Human Resource Management Journal 2015, 25, 62–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y.; Vione, K. Psychological Impacts of the New Ways of Working (NWW): A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 5080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vos, P.; Van Der Voordt, T. Tomorrow’s offices through today’s eyes: Effects of innovation in the working environment. Journal of Corporate Real Estate 2001, 4, 48–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Voordt, T. J. M. Productivity and employee satisfaction in flexible workplaces. Journal of Corporate Real Estate 2003, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunia, S.; De Been, I.; Van Der Voordt, T. J. Accommodating new ways of working: lessons from best practices and worst cases. Journal of corporate real estate, 2016, 18, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, P.; Poutsma, E.; Heijden, B. I. J. M. V. D.; Bakker, A. B.; Bruijn, T. D. Enjoying New Ways to Work: An HRM-Process Approach to Study Flow. Human Resource Management 2014, 53, 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Steenbergen, E. F.; Van Der Ven, C.; Peeters, M. C. W.; Taris, T. W. Transitioning Towards New Ways of Working: Do Job Demands, Job Resources, Burnout, and Engagement Change? 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerards, R.; De Grip, A.; Baudewijns, C. Do new ways of working increase work engagement? Personnel Review 2018, 47, 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmoll, R.; Süs, S. Working Anywhere, Anytime: An Experimental Investigation of Workplace Flexibility's Influence on Organizational Attraction. management revue 2019, 30, 40–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruostela, J.; Lonnqvist, A.; Palvalin, M.; Vuolle, M.; Patjas, M.; Raij, A. L. 'New Ways of Working' as a tool for improving the performance of a knowledge-intensive company. Knowledge Management Research & Practice 2015, 13, 382–390. [Google Scholar]

- Blok, M.; Groenesteijn, L.; Schelvis, R.; Vink, P. New Ways of Working: does flexibility in time and location of work change work behavior and affect business outcomes? Work 2012, 41, 2605–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingma, S. New ways of working (NWW): work space and cultural change in virtualizing organizations. Culture and Organization 2019, 25, 383–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Gay, P. `Without Affection or Enthusiasm' Problems of Involvement and Attachment in `Responsive' Public Management. Organization 2008, 15, 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainey, H. G. , Understanding and Managing Public Organizations. 4. ed. ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rainey, H. G.; Bozeman, B. Comparing public and private organizations: empirical research and the power of the a priori. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 2000, 10, 447–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjeldsen, A. M.; Hansen, J. R. Sector Differences in the Public Service Motivation-Job Satisfaction Relationship: Exploring the Role of Organizational Characteristics. Review of Public Personnel Administration 2018, 38, 24–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-J. Comparison of Job Satisfaction Between Nonprofit and Public Employees. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 2016, 45, 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willem, A.; De Vos, A.; Buelens, M. Comparing Private and Public Sector Employees' Psychological Contracts. Public Management Review 2010, 12, 275–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-A.; Bozeman, B. Am I a Public Servant or Am I a Pathogen? Public Managers' Sector Comparison of Worker Abilities. Public Administration 2014, 92, n/a–n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giauque, D.; Varone, F. Work Opportunities and Organizational Commitment in International Organizations. Public Administration Review 2019, 79, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, J. Y. Spurious or True? An Exploration of Antecedents and Simultaneity of Job Performance and Job Satisfaction Across the Sectors. Public Personnel Management 2016, 45, 90–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C. S. Organizational Goal Ambiguity and Job Satisfaction in the Public Sector. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 2014, 24, 955–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, B. E. The Role of Work Context in Work Motivation: A Public Sector Application of Goal and Social Cognitive Theories. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 2004, 14, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giauque, D. Attitudes Toward Organizational Change Among Public Middle Managers. Public Personnel Management 2015, 44, 70–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stazyk, E. C.; Davis, R. S. Birds of a feather: how manager–subordinate disagreement on goal clarity influences value congruence and organizational commitment. International Review of Administrative Sciences 2019, 0020852319827082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'toole Jr, L. J.; Meier, K. J. Public Management, Context, and Performance: In Quest of a More General Theory. Journal of Public Administration Research & Theory 2015, 25, 237–256. [Google Scholar]

- Collings, D. G.; Nyberg, A. J.; Wright, P. M.; Mcmackin, J. Leading through paradox in a COVID-19 world: Human resources comes of age. Human Resource Management Journal 2021, 31, 819–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coursey, D. H.; Pandey, S. K. Content Domain, Measurement, and Validity of the Red Tape Concept: A Second-Order Confirmatory Factor Analysis. The American Review of Public Administration 2007, 37, 342–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozeman, B. Bureaucracy and Red Tape; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Moynihan, D. P.; Pandey, S. K. The role of organizations in fostering public service motivation. Public Administration Review 2007, 67, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, R. Bureaucratic Structure and Personality. Social Forces 1940, 18, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P. The Dynamics of Bureaucracy; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, G. A.; Walker, R. M. Explaining Variation in Perceptions of Red Tape: A Professionalism-Marketization Model. Public Administration 2010, 88, 418–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, B. Red Tape and the Service Ethic: Some Unexpected Differences between Public and Private Managers. Administration & Society 1975, 6, 423–444. [Google Scholar]

- Dehart-Davis, L.; Pandey, S. K. Red Tape and Public Employees: Does Perceived Rule Dysfunction Alienate Managers? Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 2005, 15, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giauque, D.; Anderfuhren-Biget, S.; Varone, F. Stress Perception in Public Organisations: Expanding the Job Demands–Job Resources Model by Including Public Service Motivation. Review of Public Personnel Administration 2013, 33, 58–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borst, R. T. Comparing Work Engagement in People-Changing and People-Processing Service Providers: A Mediation Model With Red Tape, Autonomy, Dimensions of PSM, and Performance. Public Personnel Management 2018, 47, 287–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvesson, M.; Willmott, H. , Making Sense of Management. A Critical Introduction., 2nd ed.; Sage: London, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Alvesson, M. Understanding Organizational Culture; Sage: London, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, J. Organizational Culture and the Paradox of Performance Management. Public Performance & Management Review 2014, 38, 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, P. L.; Luckmann, T. The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge; Anchor Books: Garden City, NY, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P. M.; Mackenzie, S. B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N. P. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerards, R.; De Grip, A.; Weustink, A. Do new ways of working increase informal learning at work? Personnel Review 2020, 50, 1200–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lequeurre, J.; Gillet, N.; Ragot, C.; Fouquereau, E. Validation of a French questionnaire to measure job demands and resources. Revue internationale de psychologie sociale 2013, 26, 93–124. [Google Scholar]

- Steijn, B.; Voet, J. V. D. Relational job characteristics and job satisfaction of public sector employees: When prosocial motivation and red tape collide. Public Administration 2019, 97, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Job characteristics, Public Service Motivation, and work performance in Korea. Gestion et management public 2016, Volume 5 / n° 1, (3), 7-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Risher, J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C. M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C. M.; Hair, J. F., Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Homburg, C.; Klarmann, M.; Vomberg, A., Eds. Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; pp. 1–40.

- Hair, J. F.; Hult, G. T. M.; Ringle, C. M.; Sarstedt, M.; Thiele, K. O. Mirror, mirror on the wall: a comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 2017, 45, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J. F.; Cheah, J.-H.; Becker, J.-M.; Ringle, C. M. How to Specify, Estimate, and Validate Higher-Order Constructs in PLS-SEM. Australasian Marketing Journal 2019, 27, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, S. M.; Campion, M. A. Human Resource Configurations: Investigating Fit With the Organisational Context. Journal of Applied Psychology 2008, 93, 864–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Voorde, K.; Paauwe, J.; Van Veldhoven, M. Employee Well-being and the HRM–Organizational Performance Relationship: A Review of Quantitative Studies. International Journal of Management Reviews 2012, 14, 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, Y.; Giauque, D. The hybrid universe of public administration in the 21st century. International Review of Administrative Sciences 2014, 80, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, H. The Impact of Organizational Context and Information Technology on Employee Knowledge-Sharing Capabilities. Public Administration Review 2006, 66, 370–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromley, P.; Meyer, J. W. “They Are All Organizations”: The Cultural Roots of Blurring Between the Nonprofit, Business, and Government Sectors. Administration & Society 2017, 49, 939–966. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlmann, S. New public management for the classical continental european administration: Modernization at the local level in Germany, France and Italy. Public Administration 2010, 88, 1116–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steen, T., Not a Government Monopoly: The Private, Nonprofit, and Voluntary Sectors. In Motivation in Public Management. The Call of Public Service; Perry, J. L.; Hondeghem, A., Eds. Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2008; pp. 203–222.

- Vandenabeele, W. Who Wants to Deliver Public Service? Do Institutional Antecedents of Public Service Motivation Provide an Answer? Review of Public Personnel Administration 2011, 31, 87–107. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenabeele, W.; Van De Walle, S., International Differences in Public Service Motivation: Comparing Regions across the World. In Motivation in Public Management. The Call of Public Service; Perry, J. L.; Hondeghem, A., Eds. Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2008; pp. 223–244.

- Bullock, J. B.; Stritch, J. M.; Rainey, H. G. International Comparison of Public and Private Employees' Work Motives, Attitudes, and Perceived Rewards. Public Administration Review 2015, 75, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, N. B. G.; Laumann, T. V.; Jakobsen, M. Acceptance or Disapproval: Performance Information in the Eyes of Public Frontline Employees. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 2019, 29, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shantz, A.; Arevshatian, L.; Alfes, K.; Bailey, C. The effect of HRM attributions on emotional exhaustion and the mediating roles of job involvement and work overload. Human Resource Management Journal 2016, 26, 172–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leisink, P.; Andersen, L. B.; Brewer, G. A.; Jacobsen, C. B.; Knies, E.; Vandenabeele, W. Managing for Public Service Performance: How People and Values Make a Difference; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, A. L.; Irving, G.; Selvan Thevatas, K. Professional Values and Managerialist Practices: Values work by nurses in the emergency department. Organization Studies 2021, 42, 1435–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, D. E.; Ostroff, C. Understanding HRM–Firm Performance Linkages: The Role of the “Strength” of the HRM System. Academy of Management Review 2004, 29, 203–221. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, H.; Kuvaas, B. Human resource management systems, employee well-being, and firm performance from the mutual gains and critical perspectives: The well-being paradox. Human Resource Management 2020, 0, (0). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramony, M. A meta-analytic investigation of the relationship between HRM bundles and firm performance. Human resource management 2009, 48, 745–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables: | Items used: | Dimensions and Cronbach’s Alphas | |

|---|---|---|---|

| New Ways of Working (NWW) | Your organization offers flexible work arrangements. Please tell us whether you agree or disagree with the following proposals (1= I do not agree; 5= I completely agree). 1. I am free to determine my own work schedule 2. I am free to change my hours to choose when I start and finish my work3. I am free to determine where I work, at home or at work4. I am free to change where I work 5. I can find all the information necessary for my work on my computer, smartphone and/or tablet 6. I have access to all the information necessary for my work anywhere and at any time |

5 dimensions:

|

|

| Estimated model | |||

| Chi-square | 25.801 | ||

| Number of model parameters | 15.000 | ||

| Number of observations | 2733.000 | ||

| Degrees of freedom | 6.000 | ||

| P value | 0.000 | ||

| ChiSqr/df | 4.300 | ||

| RMSEA | 0.035 | ||

| GFI | 0.997 | ||

| SRMR | 0.014 | ||

| NFI | 0.996 | ||

| TLI | 0.992 | ||

| CFI | 0.997 | ||

| Well-being attribution (WB-attribution) | Consider the flexible work arrangements implemented in your organization. What are the objectives of these arrangements? (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree) Promote the well-being of employees, making them feel valued and respected |

||

| Productivity attribution (Prod-attribution) | Consider the flexible work arrangements implemented in your organization. What are the objectives of these arrangements? (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree) Increase employee productivity |

||

| Job goal clarity | In relation to the demands and constraints of your work, please tell us whether you agree or disagree with the following proposals (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree) I know exactly what is expected of me I know exactly what my job responsibilities are I know exactly what tasks I have to perform |

Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.84 | |

| Red tape | Some organizations have administrative rules and procedures that negatively affect their effectiveness. How would you rate the degree of such rules and procedures in your organization? (1 = very low; 5 = very high). |

||

| Autonomy | This section seeks to identify the main characteristics of your work, such as the level of skills required or the degree of independence. Please let us know if you agree with the following suggestions: (1= strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree) I take part in decisions about what my job entails I can participate in decisions that affect my work I am involved in decisions about the nature of my work I have direct influence on decisions made in my department/organization My job allows me to to take personal initiative |

Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.90 | |

| Cronbach's alpha | Composite reliability (rho_a) | Composite reliability (rho_c) | Average variance extracted (AVE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomy | 0.904 | 0.906 | 0.929 | 0.724 |

| Job goal clarity | 0.843 | 0.885 | 0.903 | 0.757 |

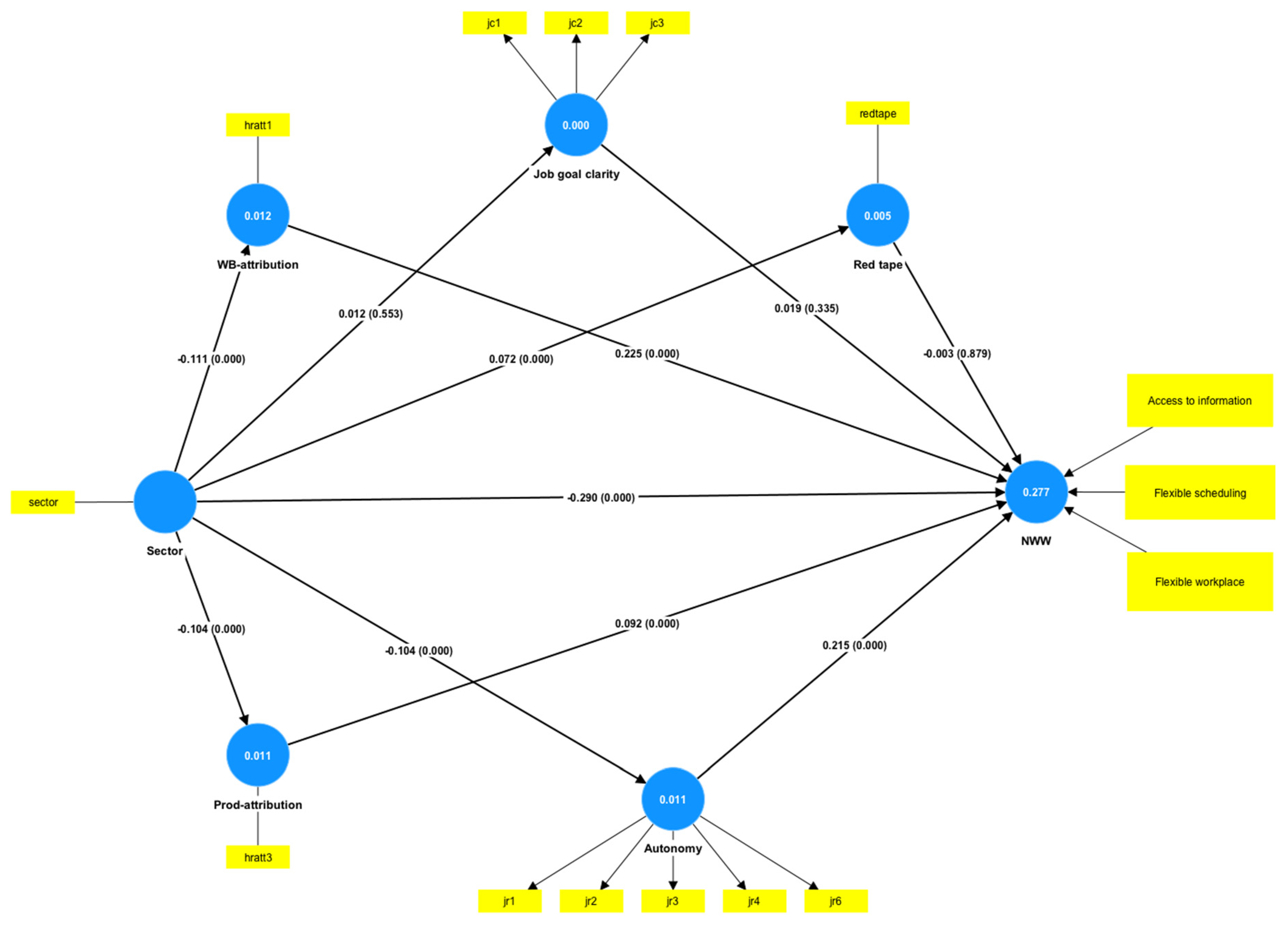

| Table 6: Path coefficients – Mean, STDEV, T values, p-values | |||||

| Original sample (O) | Sample mean (M) | Standard deviation (STDEV) | T statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p- values | |

| Autonomy -> NWW | 0.215 | 0.215 | 0.019 | 11.542 | 0.000 |

| Job goal clarity -> NWW | 0.019 | 0.019 | 0.020 | 0.970 | 0.332 |

| Prod-attribution -> NWW | 0.092 | 0.092 | 0.019 | 4.793 | 0.000 |

| Red tape -> NWW | -0.003 | -0.002 | 0.017 | 0.153 | 0.878 |

| Sector -> Autonomy | -0.104 | -0.105 | 0.017 | 6.023 | 0.000 |

| Sector -> Job goal clarity | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.020 | 0.602 | 0.547 |

| Sector -> NWW | -0.290 | -0.290 | 0.018 | 16.273 | 0.000 |

| Sector -> Prod-attribution | -0.104 | -0.104 | 0.018 | 5.634 | 0.000 |

| Sector -> Red tape | 0.072 | 0.072 | 0.018 | 4.023 | 0.000 |

| Sector -> WB-attribution | -0.111 | -0.111 | 0.018 | 6.270 | 0.000 |

| WB-attribution -> NWW | 0.225 | 0.225 | 0.021 | 10.598 | 0.000 |

| Original sample (O) | Sample mean (M) | Standard deviation (STDEV) | T statistics (|O/STDEV|) | P values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sector -> Prod-attribution -> NWW | -0.010 | -0.010 | 0.003 | 3.540 | 0.000 |

| Sector -> WB-attribution -> NWW | -0.025 | -0.025 | 0.005 | 5.355 | 0.000 |

| Sector -> Autonomy -> NWW | -0.022 | -0.023 | 0.004 | 5.221 | 0.000 |

| Sector -> Job goal clarity -> NWW | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.386 | 0.700 |

| Sector -> Red tape -> NWW | -0.000 | -0.000 | 0.001 | 0.148 | 0.882 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).