1. Introduction

In 1962, Rachel Carson analyzed the relationship between ecological conservation and economic development from the perspective of the ecosystem, which gradually make people realize the importance of ecological conservation [

1]. With the increasing severity of global climate change and biodiversity loss, the best solution to alleviate the contradiction between economic development and ecological conservation is being explored all over the world [

2,

3,

4]. Forest resources, as the main body of terrestrial ecosystems, are the most important ecological foundation for the survival and development of human society. Besides, they play an irreplaceable role in maintaining global ecological balance, guaranteeing ecological security and improving human living environment [

5]. In recent years, the conservation and development of global forest resources have received increasingly widespread attention from international organizations, national governments and the public. In response to the impact and challenges of a series of global problems, attaching importance to forests and protecting ecology has become a broad consensus of the international community and national strategies of various countries. As an important carrier of forest resources protection and forestry industry development, the use of forest land plays an important role in alleviating the contradiction between ecological protection and economic development. On the one hand, forest land, as an important part of forest resources, is an important basis for ecological environment quality and carrying capacity. Also it is an important reliance for forest existence and ecological restoration [

6]. On the other hand, forest land, as an important production factor for the development of forestry industry, is an important carrier of high-quality forestry development and an important capital for forest landowners to get rid of poverty and become rich [

7]. Meanwhile, as the main body of forest land management and utilization, forest landowners play an important role in the protection and utilization of forest resources, and their management intentions and behaviors will affect the protection of forest resources and the development of forestry industry. Therefore, foreign scholars have gradually started to focus on the research on forest landowners’ willingness [

8,

9,

10,

11] and behavior [

12,

13,

14,

15] to engage in forest management. Price (1997) concluded that factors such as forest land resource endowment and individual farmers’ characteristics have a certain degree of influence on the transformation of management behavior and willingness through the forestry production efficiency in the UK [

16]; Viitale (1998) found that reducing the input to public benefit forests inputs can appropriately change the generally low technical efficiency of production [

17]; Denis J (2011) suggested the importance of policy for developing forestry [

18]; Thant (2011) studied the role and influence of willingness and behavior of 200 households in Myanmar on achieving sustainable forestry [

19]; Goyke et al. (2019) examined the role and influence of the willingness and behavior of 200 households in Myanmar on achieving sustainable forestry through a study of selected US Southern African American forest landowners, they found that professional advice had the greatest degree of influence on forest landowners’ participation in forest management behavior [

20]; Jang-Hwan Jo et al. (2019) conducted a statistical analysis based on panel data from sustainable forest land management institutions in Korea and found that a number of elements related to the livelihood strategy level influenced farm household forestry income to varying degrees, and thus will also affect the willingness to engage in forest management and the sustainability of forestry [

21].

Collective forests as China’s important ecological barrier and forest products supply base. They can ensure the national timber and food security, cope with climate change, consolidate and expand the results of poverty alleviation. In order to give full play to the advantages of forest resources in ecological security and food security, and effectively stimulate the enthusiasm of forest landowners to engage in forest management, the General Office of the CPC Central Committee and the State Council in China issued the “Opinions on Comprehensively Promoting the Reform of Collective Forest Rights System”. The Opinions determined the foresters’ rights to use and engage in forest management and ownership of forest trees, and foresters gained the autonomy to engage in forest management. Through the collective forest reform, the cultivation of collective forest resources has been strengthened, and the forest stock of collective forests nationwide has increased by nearly 2.4 billion cubic meters compared with that before the forest reform. The transfer of collective forest rights has been steadily promoted, and the number of new business entities reached 294,300, operating more than 280 million mu of forest land. In recent years, although the reform of collective forest rights system has achieved good results, the productivity of collective forest land has not yet been fully released, the comprehensive benefits and operational efficiency of collective forestry [

22] are still not high, the economic income from forestry for forest landowners is relatively small [

23]. The enthusiasm of forest landowners and social capital to engage in forest management is not high, so how to pass the “last kilometer” to realize the ecological beauty and wealth of the people has become an urgent problem. The “last kilometer” has become an urgent problem to be solved. At the same time, with the continuous promotion of the reform of collective forest rights system, the management status of forest landowners, the characteristics of their management behavior and their willingness of management have become the focus of academic research in the process of forest landowners’ utilization. With the development of modern forestry, forest landowners’ management of forest land has developed from decentralization and diversification to centralization and unification [

24,

25], and joint-family operation and moderate scale operation can make up for the shortcomings of single-family operation and decentralized operation in terms of technology, efficiency, and cost [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. In addition, domestic scholars have found that there is often a gap between the consistency of forest landowners’ willingness of management and their operating behavior, and forest landowners with willingness to engage in forest management may not actually have operating behavior, and there are many influencing factors for the conversion of this [

26], such as forest land resource endowment [

31], individual forest landowners’ characteristics [

32], policy compensation [

33], and operating philosophy [

34]. For example, Xie concluded that factors such as forest land resource endowment and individual farmers’ characteristics have some influence on achieving the transformation of forest land management behavior and willingness through a study of 10 forest counties in Jiangxi Province [

35].

Yunnan Province is not only an ecological barrier in the southwest region, but also a community of ecological destiny and ecological interests with the people of South Asia and Southeast Asia. It undertakes the strategic task of safeguarding China’s and even international ecological security [

36]. Over the years, Yunnan Province has continuously strengthened cross-border biodiversity conservation and cultural exchanges with neighboring countries such as Laos, Vietnam, and Myanmar, and held the “China-Myanmar Forest Resources Protection and Community Development Forum” and the “China-Myanmar Forestry Cooperation Group First Consultation”. At the same time, the Greater Mekong Subregion, as a bridge connecting China’s southwestern region and Southeast Asian countries, the effective utilization and protection of forest resources and forest ecological restoration have increasingly become a hot issue in the Lancang-Mekong River Basin, especially the poverty problem [

37]. In addition, Yunnan, as a frontier province of Lancang-Mekong poverty reduction cooperation, actively exchanges poverty reduction experience with Mekong countries and continuously promotes the sustainable development of forestry in the Greater Mekong Subregion. For example, Myanmar and Yunnan use bamboo and rattan as a forestry poverty reduction product [

38], northeastern Thailand [

39] and northern Laos select ecotourism as a forestry poverty reduction breakthrough, Vietnam adopts a community forestry plan [

40], Cambodia’s community-based management of forestry [

41] makes forestry resources play a role or have a significant effect in poverty reduction. It is found that Yunnan and Thailand in China have made them the most effective countries or regions in poverty reduction in the Lancang-Mekong Basin through government-led or community-led approaches. However, due to historical reasons and production conditions, the fragmentation of land, the difficulty to engage in forest management and the increase of cost, especially in Yunnan minority regions, the low utilization rate of forest resources is serious, which has hindered the sustainable development of forestry and the sustainable livelihood of forest landowners. Based on the perspective of resource economics, the “tragedy of the commons” caused by the idle and excessive use of forest resources in efficiency is similar [

42]. Therefore, in this context, how to make full use of forest resources and explore forest landowners’ willingness of management has become a research focus on promoting the coordinated development of forestry ecology, economy and society in minority regions. As the direct subject of the protection and utilization of forest land resources, the willingness of forest landowners will affect the utilization and management efficiency of forest land, it will also have a certain impact on the accurate quality improvement of forest resources. Based on this, this study takes sustainable livelihoods as the analysis framework, takes typical minority regions in Yunnan Province as the research object, discusses the willingness of forest landowners’ management in minority regions and its influencing factors. Finally, we put forward countermeasures and suggestions to improve the willingness of minority regions’ farmers to manage, so as to promote the high-quality development of forestry industry and the accurate improvement of forest quality in minority regions of Yunnan Province. This paper can not only promote the improvement of farmers’ forest land management willingness and protection awareness in minority regions, but also realize the symbiosis of forestry industry and ecological protection. At the same time, it will also provide reference for neighboring countries or regions in Yunnan Province on forest land management, ecological poverty reduction and industrial development, with a view to jointly promoting the high-quality development of forestry.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area Overview

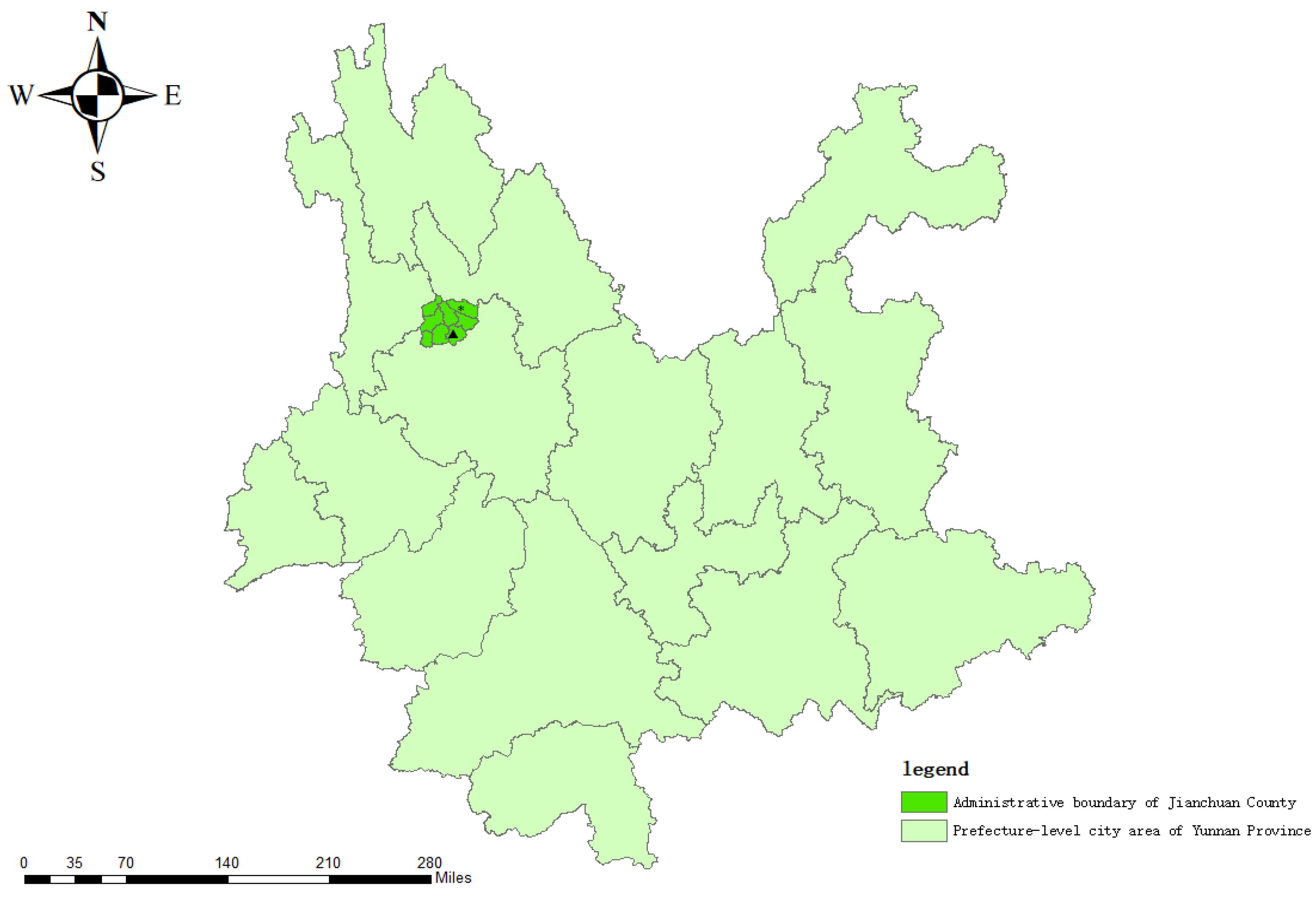

Jianchuan County located in the northwest of Yunnan Province and the north of Dali Prefecture, neighboring Heqing in the east and Lijiang in the north. It with a mountainous area of nearly 90% of the territory, and 96.2% of the county’s population is made up of minoritie. And the Bai accounting for 91.2% of the total population (

Figure 1). Jinhua and Shaxi are the two most populous townships (communities) in Jianchuan County, and are also rich in woodland resources. Jinhua community is dominated by public welfare forests, while Shaxi township has timber forests, economic forests, charcoal forests, protective forests, and other multi-purpose forests.

Pingbian County located in the south of Yunnan Province and the southeast of Honghe Prefecture, south of the Tropic of Cancer. It with wet and rainy forests and a forest coverage rate of 68.3%, and has the reputation of “natural oxygen zone “ (

Figure 2). The county’s minority population accounts for 67.5%, and is the only Miao autonomous county in Yunnan Province, with 44.68% of the county’s total population being Miao. The case sites were selected in Baihe Township and Baiyun Township of Pingbian County, where timber forests and ecological public welfare forests account for a relatively large area.

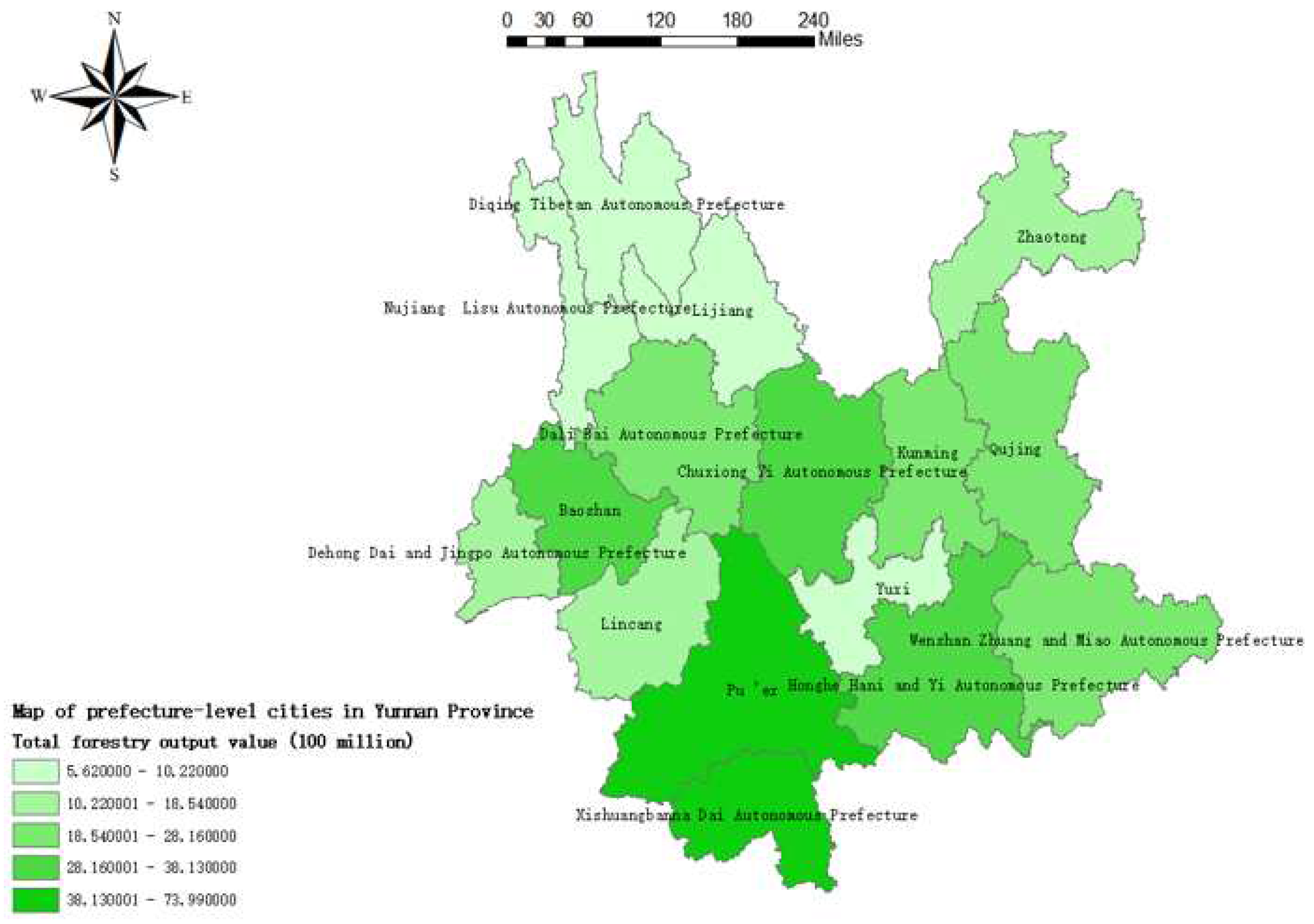

The case sites are located in states with abundant forest resources, and the data on the total forestry output value of each state and city from the 2021 Yunnan Statistical Yearbook are collated and divided. The two states are in the middle to upper class, with sufficient endogenous power for forestry industry development, and the study of forest land management behavior and willingness of their unique ethnic forest landowners is somewhat representative (

Figure 3).

2.2. Data sources

Since the full implementation of the collective forest rights system reform in Yunnan Province in 2007, a large amount of forest land resources has been allocated to ecological public welfare forests and natural forest protection areas. In order to gain an in-depth understanding of the basic overview of forest land management in minority regions of Yunnan after the collective forest rights system reform, the group was commissioned by the comprehensive research and evaluation project team of Peking University on August 23-September 4, 2021 to conduct a field The survey was conducted mainly by distributing forest landowner questionnaires and conducting structured interviews with groups such as village elders, forestry leaders, village cadres, and township leaders. The survey content focused on several aspects such as basic information of forest landowners, forest land management behavior, management mode, management intention and its influencing factors. The research team was divided into 2 groups, and the investigators were all enrolled through the recruitment system of collective forest rights system visitors, and were all college students or graduate students majoring in rural development, urban and rural planning, agricultural and forestry economic management, etc. Among the 5 investigators in Jianchuan County, 3 of them were local people from Jianchuan County; 1 of the 5 investigators in Pingbian County was a local person from Pingbian County. Under the leadership of the two county forestry and grassland bureaus, the investigators first conducted interviews with county leaders and explained the reason for the survey, followed by village leaders and village group leaders who led the investigators to interview households. The survey workers were issued to a total of 185 points of questionnaires, including 101 in Jianchuan County and 84 in Pingbian County. The survey randomly selected a total of 185 minority households including Bai, Yi, Lisu, Miao, etc. as interviewees, of which the number of valid questionnaires was 182, with an efficiency rate of 98.38%.

The field survey involved 185 minority farming households of 8 minority regions’ groups in 10 villages in Jianchuan and Pingbian counties of Yunnan Province (

Table 1).

2.3. Variable selection

The Sustainable Livelihoods Framework (SLA) is a research tool based on the British Development Agency, which has been widely used in livelihood vulnerability analysis [

43], poverty [

44]. At the same time, it can also consider the influencing factors and willingness of its behavior from the perspective of farmers, [

45] which can intuitively reflect the problems and needs at the micro level. William D.Sunderlin et al.summarized and summarized the research literature related to rural livelihoods such as forest resource protection, utilization, and poverty reduction in some developing countries [

46]. Nimai Das studied the impact of participatory forestry programs on rural livelihood sustainability in some poor households in India [

47]. The sustainable livelihood framework is also used as a research tool in the research on the sustainable development of grassland ecosystem [

48], the implementation effect of grassland ecological compensation policy [

49], joint forest management [

50] and other fields related to forestry ecological development. Therefore, the existing research and application of the SLA framework has been more common and extensive. The research areas are mostly concentrated in poverty-stricken areas, remote minority regions’ areas [

51], etc. The research content is mostly focused on the livelihood status of farmers, the livelihood factors that affect the income level or behavior of farmers, etc. There are few studies on ecological key functional areas such as Yunnan Province, and there are few studies on the influencing factors of SLA framework for the willingness of minority forest landowners to engage in forest management.

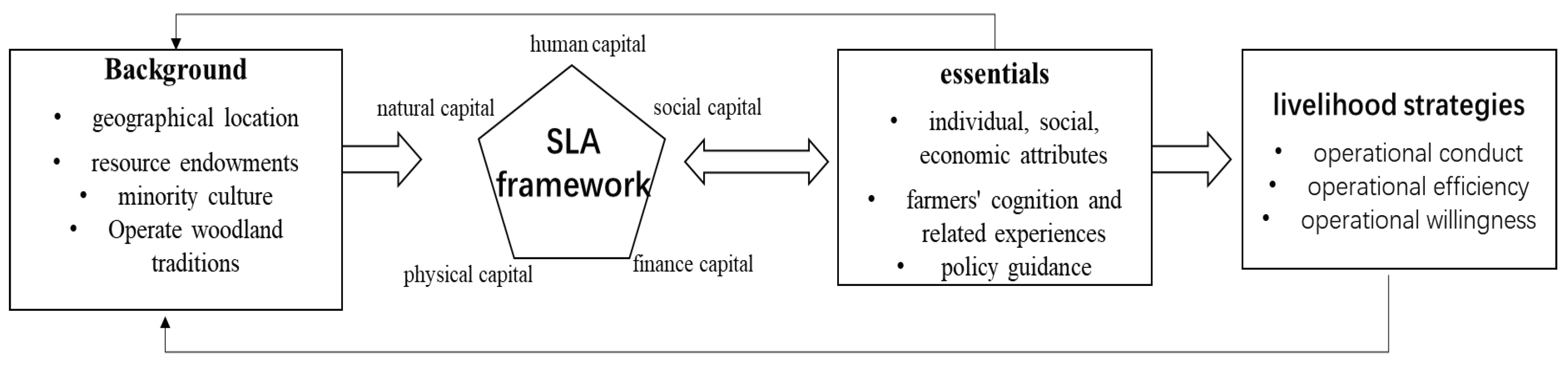

Forest land resources are the key production factors for landowners in minority regions to develop forestry industry. Forest landowners in minority regions are influenced by the traditional behaviors of their ancestors, from the primitive tribal group lifestyle to the traditional smallholder management model to modern management, and their production and living behaviors such as hunting and harvesting, food customs, and firewood construction are all involved in forest land management in a direct or indirect way, showing a high degree of dependence on forest resources by farmers in minority regions. This paper draws on human capital, natural capital, physical capital, financial capital, and social capital [

53] from the sustainable livelihood analysis framework (SLA) [

52], which can visually reflect the strengths or weaknesses of forest landowners in minority regions in terms of various capital elements in forest land management (

Figure 4).

Therefore, according to the SLA framework and combined with the field survey results, we used factors such as forest landowners’ identity, education level, living standard, forest land area, and forest land function type as indicators to respond to the influence of forest landowners’ individual level, economic level, and social level on the willingness of management, which will govern forest landowners’ operation efficiency and perception of operation risk. At the same time, the perceptions of joint-family operation and large-scale operation, and the participation in the project of returning farmland to forests and grasses were also used as variables influencing forest landowners’ perceptions and related experience levels on management intentions. In addition, the three variables of compensation for public welfare forests, satisfaction with collective forest rights system reform, and the strength of harvesting limit policy constraints will also reflect whether policy guidance has a subjective-level effect on minority forest landowners’ management intentions.

Adding to this, there are 3 points to think about for forest landowners in minority regions: first, forest landowners in minority regions may have stronger minority plot and land plot, and their deep-rooted beliefs form a self-protection mechanism compared to the management behavior and willingness of forest landowners in non-minority regions, so that even if they do not manage forest land, they will not engage in transfer behavior and are more willing to grasp forest land resources in their own hands or pass them on to the next generation. Second, based on the geographical characteristics and resource endowment of minority regions, the distance between forest plots and the problem of fragmentation are more prominent, which affects the forest revenue and the implementation of mechanized operations; and farmers, as rational economic people, the forest revenue directly affects the management behavior and thus the willingness to engage in forest management, and there are always some obstacles to the transformation of management behavior and willingness. Third, the proportion of ecological public welfare forests in Yunnan’s minority regions is high, and the harvesting target and quota policy greatly limit forest landowners’ enthusiasm and willingness of management.

In summary, three research hypotheses are proposed.

Hypothesis 1:

Individual socioeconomic attributes of forest landowners are conducive to strengthening forest landowners’ willingness to engage in forest management.

Hypothesis 2:

Forest landowners’ perceptions and related experiences are conducive to strengthening forest landowners’ willingness to engage in forest management.

Hypothesis 3:

Policy guidance is conducive to strengthening forest landowners’ willingness to engage in forest management.

The dependent variable is the willingness to engage in forest management, and about the willingness of citizens to act on land at the individual level as the dependent variable can be indexed subjectively to relevant studies [

54,

55,

56,

57,

58]. It was found that the subjective variables reflect the future behavior or preferences of individuals, and that the answers of the studies differed from one respondent to another and from one geographical area to another [

59] and were somewhat comparable.

As shown in

Table 2, in terms of the factors at the level of individual socioeconomic attributes of farmers, based on human capital and social capital considerations in the sustainable livelihoods framework, individual and social resource and capital endowments have different degrees of influence on forest management behavior, philosophy, and willingness; therefore, the factors that affect the willingness to engage in forest management include farmer’s identity, education level, living standard, forest land area [

60], forest land function type, and other factors that will constrain forest landowners’ management efficiency, future management risk, and judgment of management philosophy. In terms of factors at the level of forest landowners’ perceptions and related experiences, forest landowners judge the ease of future operation and benefits based on their perceptions of the operation mode [

61] and their actual participation in forestry-related projects in the past [

62], so as to assess whether it is worthwhile to continue operation in the future, and therefore, three variables including the perceptions of joint-family operation and large-scale operation, and the participation of returning farmland to forestry and grass are summarized. In terms of influencing factors at the policy guidance level, social capital considerations based on the sustainable livelihood framework can achieve subjective regulation and incentive effects on forest landowners’ willingness of management [

63,

64], including three variables of being subject to compensation for public welfare forests, satisfaction with collective forest rights system reform, and the strength of harvesting quota policy constraints.

2.4. Research Methodology

In the existing studies on the empirical analysis of factors influencing behavioral intentions, more models are used such as Probit regression model [

65], structural equation model [

66], and logistic regression model [

67]. With reference to the existing research and combined with the questionnaire data, the logistic regression model will be selected for the empirical analysis in this paper. In addition, the Y variable in this paper is a dichotomous variable, so the binary logistic regression model in the logistic regression model is used to analyze the influencing factors of different levels of forest landowners’ willingness to engage in forest management in minority regions.

First, we processed the data. In the study of forest landowners’ willingness to engage in forest management in minority regions, forest landowners’ identity, scale of operation, and living standard are all influencing factors, and variables such as forest landowners’ identity and living standard belong to a fixed category of data. First of all, we conduct data processing. When studying the impact of forest landowners ‘ willingness to engage in forest management in minority regions, forest landowners ‘ identity, scale management, living standards, etc. are all influencing factors. Variables such as forest landowners ‘ identity and living standards belong to categorical data. Therefore, virtual variable processing is carried out. Taking ‘ forest landowners ‘ identity ‘ as an example, the assignment of the answer option as ‘ cadres ‘ is 1, and the assignment of the answer option as ‘ ordinary people ‘ is 0.

Secondly, after completing the above data processing, the Y variable is encoded. Forest landowners in minority regions have two options of ‘willing’ and ‘unwilling’ for forest land management, which is a binary variable and a typical binary selection model. We assign a value of 1 to the willingness to engage in forest management and 0 to the non-willingness to manage. It is assumed that the error term obeys the Logistic distribution.

Second, after completing the above data processing, the data coding of Y variable was started. Forest landowners in minority regions have two options of “willing” and “unwilling” to engage in forest management, which is a dichotomous variable and belongs to a typical binary choice model. We assign a value of 1 to those who are willing to manage and 0 to those who are not willing to manage, and assume that the error term follows a logistic distribution.

Finally, the analysis of the influence relationship, binary logistic regression analysis, was performed. We first determine whether an influence factor appears to be significant (if the p-value is less than 0.05, then it is significant at the 0.05 level), and if it appears to be significant, then the independent variable has an influential relationship on the dependent variable of willingness to engage in forest management. After determining the influence relationship, the analysis was conducted in conjunction with the regression coefficient value, if the regression coefficient value is greater than 0, the influence relationship is positive, and vice versa, it is negative.

The binary logistic model equation is as follows:

Where: P(Y=1) represents forest landowners’ willingness to engage in forest management, P(Y=0) represents forest landowners’ lack of willingness to engage in forest management; denotes the ith influencing factor; α denotes the constant term; denotes the estimated parameter; denotes a random variable obeying Logistic distribution, and P(Y=1|X1,X2,X3•••Xi) is the probability that forest landowners in minority regions hold willingness to engage in forest management under the influence of i independent variables.

3. Results

3.1. Model regression results and tests

As shown in

Table 3, the model was evaluated or validated for validity and the overall model fit was: likelihood = 158.414, p = 0.000, which was significant at the level and rejected the original hypothesis, thus indicating that the model fit was good and valid overall. The classification effect of logistic regression can be measured in the evaluation results of classification indexes, where the value of accuracy is 0.808, which predicting the proportion of correct samples to the total samples, and the closer the value is to 1, the more the number of correct samples in the model classification evaluation indexes. The value of F1 reflects the reconciled average of accuracy and recall of the survey data, and the value is 0.794, which is a good effect; the value of AUC value is 0.836, which is closer to 1, indicating the better classification effect of the indicators, which also proves that the classification of factors influencing forest landowners’ willingness to engage in forest management in minority regions according to the sustainable livelihood framework is consistent with the model regression.

3.2. Effectiveness of Collective Forest Rights Reform and Forest landowners’ Willingness to engage in forest management

(1) The reform of collective forest rights system in Yunnan Province is effective. According to the questionnaire data, the number of plots owned by forest landowners in the case sites, the percentage of plots with forest land right certificates is 93.53%, among which 64.8% of minority regions’ forest landowners said they obtained forest land right certificates in 2007. This is at the stage of comprehensive reform of collective forest rights system in Yunnan Province, where clear property rights provide rights protection for activities such as forest land management, adjustment of disputes, and application for logging. And very few forest landowners (5.59%) used forest right certificates to mortgage loans to obtain operating capital, which indicates the special behavior and conservative attitude of forest landowners in minority regions towards mortgage risk and operating financing (

Table 5).

(2) Forest landowners’ willingness to produce and manage is strong. Among the 182 valid questionnaires collected, 131 minority forest landowners have the willingness to engage in forest management, accounting for 71.98%; 51 minority forest landowners do not have the willingness to engage in forest management, accounting for 28.02%. The main reasons for their unwillingness to engage in forest management were the low subsidy standard for public welfare forests and policy restrictions, and the high proportion of no harvesting targets, 41.18% and 27.45%, respectively (

Table 6), while some forest landowners responded that they were unwilling to continue to manage their forest land due to low income, the distance of the forest land, and the inconvenience of management.

4. Discussion

This paper makes up for the lack of micro-level studies related to minority regions and summarizes the behavior of forest landowners’ management in minority regions and their willingness to influence. At the same time, we answer the question based on the micro-level perspective to explain the reasons why farmers in minority regions manage forest land under the influence of different levels of philosophy, endowment, and policy, which lead to different results from those of studies in non-minority regions.

4.1. Significant differences in the influence of individual socioeconomic attributes of forest landowners on willingness to engage in management

(1) Literacy. The regression results showed a negative effect of “more education” and “less education” on the willingness of forest land management. The regression results show that literacy has a negative effect at the 1% significance level, indicating that the more educated forest landowners in minority regions are, the less willing they are to manage forest land, which is inconsistent with their hypothesis. Rong Niu also found a negative effect of literacy in his survey on the willingness of creditors to lend on farmland management rights in the western region [

68]. The reasons for this may include: first, the higher the literacy level, the easier it is for forest landowners to obtain stable, well-paid jobs, and the more willing they are to work outside the home to sustain their livelihoods, with higher opportunity and sunk costs of giving up their current positions. Secondly, forest landowners with relatively less education have earlier access to agricultural production and management activities and become the main force of forest land management. Compared with forest landowners with more education and schooling, their land sentiment is deeper, and they have fewer channels to obtain other sources of income and less sensitive information, which directly affects their behavioral attitude and willingness.

(2) Living standard. The effect of living standard on the willingness to engage in forest management was measured by the two options of “poor” and “rich”. The regression results show that the living standard has a positive effect at 1% significance level, forest landowners with relatively lower living standard are more willing to engage in forest management. In a study on multidimensional poverty in rural Bihar, India, Manjisha Sinha found that forest landowners with higher dependence on livelihood activities such as forestry and higher poverty levels were more affected by climate change and their business behavior is more influenced by objective factors [

69]. In contrast to the behavior of forest landowners in these areas without minority regions’ characteristics, the willingness of farmers in minority regions to manage is instead more influenced by subjective factors. Possible reasons for this are as follows: first, forest landowners with relatively low living standards have a weaker ability to bear risks, and agricultural production and management activities are less risky compared to other industries; while forest landowners with relatively high living standards have certain financial ability and prefer investment-oriented activities, and their behavioral attitudes make the willingness to engage in forest management in the future smaller. Secondly, the long payback period of forest land investment, low income and low efficiency of production, and the special nature of operation make the income cannot meet people’s living needs.

(3) Woodland area. The actual value of woodland area was used as an economic attribute variable to analyze the effect on forest landowners’ willingness of management in terms of mu (1 ha = 15 mu). The regression results show that woodland area has a positive effect at the 1% significance level, forest landowners with more woodland area are more willing to continue operating their woodlands. The per capita forest land area of the case sites reached 13.84 mu, which just confirms that forest landowners in minority regions have been in the forest-centered ecosystem for a long time and have more minority regions’ land sentiment, and the endowment of forest resources in minority regions provides an important material basis for farmers to maintain their livelihoods. Despite the ineffectiveness of forest land management, farmers who own more forest land are more willing to keep the resources in their own hands and have greater expectations of forest land, while comparing to some forestry households in Korea, the magnitude and direction of the impact of different acreage on different income types are inconsistent [

70], which is the difference in behavioral attitudes of farmers in minority regions compared to farmers in non-minority regions in terms of forest land management behavior and willingness.

4.2. Influence of forest landowners’ perceptions and related experiences on willingness to engage in forest management

Among the three variables of forest landowners’ perceptions and related experiences, most of the forest landowners in the minority regions studied did not participate in the large-scale management and joint-family management of forest land, so they did not know much about the concept, and thus these two variables did not have a significant effect on the willingness to engage in forest engagement. Only “ whether or not they have participated in the project of returning farmland to forest and grass” has a negative effect on the willingness to engage in forest management at 1% level of significance, which is not consistent with the expected hypothesis. However, the respondents were more satisfied with the policy of “returning farmland to forest and grass”, while the willingness of farmers in non-minority regions was more different [

71]. It may be due to the fact that most of the forest landowners used to cultivate food and burn firewood to cut firewood, but they had to change their cultivation habits due to policy restrictions after the implementation of the project; secondly, the basic farmland and non-basic farmland are intertwined in most of the minority regions in Yunnan, which makes the forest land more fragmented and more difficult to manage, and the subsidies for returning farmland to forest and grass are not proportional to their expectations. This has a direct impact on the attitude of forest landowners, which leads to a low willingness of forest landowners to engage in forest management.

4.3. Impact of policy guidance on willingness to engage in forest management

Among the three variables of policy guidance, ‘ whether it is compensated by public welfare forest ‘ has a significant negative impact on the willingness of forest land management, which is inconsistent with expectations. This is a special phenomenon in the factors affecting forest landowners’ willingness to manage in minority regions. Generally speaking, compensation tends to increase farmers ‘ willingness to engage in forest management [

72]. The reasons for this may be as follows: first, the proportion of ecological public welfare forests in minority regions is high, forest landowners are more restricted by the logging quota policy and the comprehensive ban on natural forests, they do not understand enough the institutional policy constraints, and with the increase of ecological awareness, the enthusiasm of management is greatly frustrated, and forest landowners prefer to keep the forest land use, ownership and use rights in their own hands. Secondly, during the research process, forest landowners, management entities and village leaders all gave feedback on the low compensation standard of ecological public welfare forests, reflecting the fact that the subjective norms of the policy directly affect forest landowners’ own economic rationality, thus leading to the occurrence of different management behavior and willingness.

In other scholars’ studies, it was found that, in terms of geographical location conditions, the more developed areas in east-central China, areas with good forestry resource endowment, and areas with significant reform are relatively more efficient in developing forestry and more effective in large-scale operation [

23], and academic research hotspots are also focused on relevant regions with more diversified business models and relatively obvious farmers’ willingness to engage in forest management, as concluded by Han [

73], Zheng [

24], and Hu [

74] in related studies; however, in this study, it is found that the factors of scale operation and diversification have no effect on the willingness of minority farmers to engage in forest management.

4.4. Research shortcomings and outlook

Through the empirical analysis of the behavioral performance and willingness of minority regions’ farmers regarding forest land in Jianchuan and Pingbian counties, the shortcomings of forest landowners in minority regions in terms to engage in forest management ideology and behavioral characteristics were found. The innovation of this paper is to adopt the framework of sustainable livelihood analysis from a sociological perspective as the theoretical support, and to explain the unique management behavior and willingness trends of forest landowners in minority regions from different perspectives such as ethnology and ecology, and to draw conclusions that are both identical to academic studies and reflect differences from non-minority regions in terms of the research results and the direction of the influence of factors on willingness.

Of course, there are some limitations in the study of this paper. There are 25 minority groups living in Yunnan Province, and this study only analyzes 8 of them, lacking research on the unique minority regions’ groups. Secondly, this study was commissioned by Peking University’s comprehensive research and evaluation project team of collective forest rights system reform to conduct a survey in Jianchuan and Pingbian counties. Since the questionnaire design mainly focuses on the content of reform effectiveness, the variables selected are limited, and the results of specific measurement of the factors influencing forest landowners’ willingness to manage in minority regions should vary according to the actual location and variables. Therefore, the follow-up study should focus on the dynamic follow-up of the factors influencing forest landowners’ willingness to engage in forest management in minority regions at the specific minority and micro levels.

5. Conclusions

A study was conducted on 185 minority farming households of 8 minority regions’ groups in 10 villages in Jianchuan and Pingbian counties, and a binary Logistic model was used to empirically analyze the effects of 3 dimensional variables, namely individual socio-economic attributes of farming households, cognitive and related experiences of farming households, and policy guidance, on willingness to engage in forest management. The results of the study show that: living standard and forest area have a significant positive influence on the willingness to engage in forest management, and literacy, whether or not they have participated in returning farmland to forest and grass, and whether or not they have been compensated by public welfare forest have a significant negative influence on the willingness to engage in forest management, while the rest of the variables have no significant influence on the willingness to engage in forest management of forest landowners in minority regions, and there are results that do not match with expectations. Compared with the factors influencing the management behavior and willingness of forest landowners in non-minority regions, the possible reasons for this are summarized as landscape, resource endowment, minority regions’ sentiment, historical habits, beliefs in ecological forestry concepts, etc.

First, the impact of individual socio-economic attributes variables on forest landowners’ willingness to engage in forest management is relatively significant. Since personal and economic capital are still at a low level, which greatly restricts landowners’ willingness to forestry, the main labor force of the family has to go out to work to maintain their livelihood, and there is also a phenomenon of talent spillover, and the older people become the main force of forest land management, and the plight of forest landowners in minority regions who cannot transform their “green hills” into “golden mountains” needs to be solved. Therefore, the government should promote large-scale forest land management to improve the efficiency of forest land management and strengthen the collective economy, so that the resource endowment can retain young and high-quality talents and make full use of the collective forest land that has not been divided into households. At the same time, the government should encourage new business entities to drive forest landowners to participate in forest land management, stimulate family capital and social capital to invest in diversified forest land management, improve forestry income to enhance the living standard of forest landowners, and place surplus rural labor in forest management to realize “employment close to home”.

Secondly, forest landowners’ cognition and related experiences have a significant negative impact on their willingness to engage in forest management “whether or not to participate in the fallow forestry and grass restoration project”. Considering the special resource endowment, landscape characteristics and minority regions’ sentiment in minority regions, the government can help by extending the subsidy period and increasing the subsidy standard, and strengthen scientific and standardized management according to the conditions of different fallow land plots. Since minority regions’ forest landowners have very low understanding of large-scale operation and joint-family operation, the government should reasonably adjust the plots to realize concentrated and large-scale operation, which will also break through the limitation of forest land fragmentation. In addition, forest landowners in minority regions should learn from the ancient ancestors’ concept of “knowing the land and making good use of it”, integrate the ecological wisdom of “slash-and-burn” forestry into modern management, and incorporate ecological ideas such as minorities’ beliefs and forest culture into mountain forest fire prevention and forest management to improve the effectiveness of forest resource protection.

Third, the analysis of the impact of public welfare forest compensation standards on the willingness of forest land management shows that the government should firmly establish the management concept of “logging is not equal to destruction, and not logging is not equal to protection”, appropriately adopt the measures of planting and cultivating, combining conservation and rotating logging limits, and from the perspective of “decentralization-management-service” actively promote logging indicators “into the village into the household”. At the same time, the government should coordinate the contradiction between the significant advantages of ecological resources in minority regions and the lagging management efficiency of forest land, scientifically utilize forest resources, and guarantee the sustainable development of forest resources.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.C. and Y.L.; methodology, H.C.; validation, H.C. and Y.D.; model analysis, H.C.; investigation, H.C. and Y.L.; resources, Y.L.; data curation, H.C.; writing—original draft preparation, H.C.; writing—review and editing, Y.D. and X.Z.; supervision, Y.D. and X.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the project “Comprehensive Survey and Evaluation of Collective Forest Rights System Reform”, Department of Development and Reform, National Forestry and Grassland Administration.

Informed Consent Statement

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any authors. Informed consent was obtained from all the individual participants included in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

All authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the people’s governments of Jianchuan County and Pingbian County, village leaders, business entities and minority regions’ forest landowners for their support of this survey. In particular, the project team for comprehensive investigation and evaluation of collective forest rights system Reform of Peking University has handled the survey and provided detailed survey data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Parks, P. Silent Spring, Loud Legacy: How Elite Media Helped Establish an Environmentalist Icon. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 2017, 94, 1215–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.X.; Liu, Z.X.; Li, W.M.; et al. Balancing ecological conservation with socioeconomic development. Ambio 2021, 50, 1117–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hametner, M. Economics without ecology: How the SDGs fail to align socioeconomic development with environmental sustainability. Ecological Economics 2022, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, W.E. Economic development and environmental protection: An ecological economics perspective. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2003, 86, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauppi, P.E.; Sandstrom, V.; Lipponen, A. Forest resources of nations in relation to human well-being. PLoS ONE 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, R.; Grundy, I.M.; van der Horst, D.; et al. Environmental incomes sustained as provisioning ecosystem service availability declines along a woodland resource gradient in Zimbabwe. World Development 2019, 122, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Q.R.; Kan, L.B.; Tsai, S.B. Analysis on Forestry Economic Growth Index Based on Internet Big Data. Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czajkowski, M.; Barczak, A.; Budziński, W.; et al. Preference and WTP stability for public forest management. Forest Policy and Economics 2016, 71, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekanayake, E.; Xie, Y.; Ahmad, S. Rural Residents’ Participation Intention in Community Forestry-Challenge and Prospect of Community Forestry in Sri Lanka. Forests 2021, 12, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halalisan, A.; Abrudan, I.; Popa, B. Forest Management Certification in Romania: Motivations and Perceptions. Forests 2018, 9, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubair, M.; Garforth, C. Farm Level Tree Planting in Pakistan: The Role of Farmers’ Perceptions and Attitudes. Agroforestry Systems 2006, 66, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, M.A.; Hartter, J.; Congalton, R.G.; et al. Characterizing Non-Industrial Private Forest Landowners’ Forest Management Engagement and Advice Sources. Society and Natural Resources 2019, 32, 204–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dung, N.V.; Thang, N.N. Forestland rights institutions and forest management of Vietnamese households. Post-Communist Economies 2017, 29, 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karki, L.B.; Karki, U.; Tiwari, A. Woodland Grazing: Untapped Resource to Increase Economic Benefits from Forestland. Journal of Animal Science 2021, 99, 7–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J.E. Ruminations on Economic Decision Modeling of Managing Forest Resources with a Focus on Family Forest Landowners. Journal of Forestry 2020, 118, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, C. Twenty-five years of forestry cost—Benefit analysis in Britain. Forestry: An International Journal of Forest Research 1997, 70, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viitala, E.-J.; Hänninen, H. Measuring the efficiency of public forestry organizations. Forest Science 1998, 44, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonwa, D.J.; Walker, S.; Nasi, R.; et al. Potential synergies of the main current forestry efforts and climate change mitigation in Central Africa. Sustainability Science 2011, 6, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thant, C. Sustainable agro-forestry in Myanmar: From intentions to behavior. Environment, Development & Sustainability 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyke, N.; Dwivedi, P.; Thomas, M. Do ownership structures effect forest management? An analysis of African American family forest landowners. Forest Policy and Economics 2019, 106, 101959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, J.H.; Roh, T.; Shin, S.; et al. Sustainable Assets and Strategies Affecting the Forestry Household Income: Empirical Evidence from South Korea. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.N.; Wei, Y.M.; Fang, W.; et al. New Round of Collective Forest Rights Reform, Forestland Transfer and Household Production Efficiency. Land 2021, 10, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Xiao, H.; Liu, C.; et al. The Impact of Collective Forestland Tenure Reform on Rural Household Income: The Background of Rural Households’ Divergence. Forests 2022, 13, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.F.; Ma, M.Y.; Sun, X.X.; et al. Comparative Analysis of Changes in Forest Management Methods Before and after the Reform—A Case Study of Fujian, Zhejiang and Jiangxi. Forestry Economics 2011, 11, 27–30. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, G.C.; Harris, V.; Stone, S.W.; et al. Deforestation, land use, and property rights: Empirical evidence from Darien, Panama. Land Economics 2001, 77, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.P.; Wang, L.; Liao, W.M. Policy Guidance, Poverty Level and Farmers’ Forestry Scale Management Behaviors. Problems of Forestry Economics 2020, 40, 147–154. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.B.; Su, S.P.; Zheng, Y.F.; et al. Analysis the Differences of Fujian Farmer Forestry TFP in Different Operation Scale after the Reform of Forest Property Right System. Forestry Economics 2014, 36, 55–59+78. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Peng, P.; Chou, X.L.; Zhao, R. Reality Analysis and Implementation Pathway of Scale Forest Management in Collective Forest Area in China. World Forestry Research 2018, 31, 86–90. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tian, J.; Shi, C.N. Allocation Efficiency of Forestry Producing Factors in Different Forest Land Scale Farmer and its Influencing Factors. Issues of Forestry Economics 2017, 37, 73–78+109. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Alchian, A.A.; Demsetz, H. Production, Information Costs, and Economic Organization. IEEE Engineering Management Review 1972, 62, 777–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, L.H.; Su, S.P.; Chen, S.F.; et al. Forest Fragmentation’s and Forest Land Circulation Behavior’s Impact on Efficiency of Forest Resource Allocation. Resource Development & Market 2016, 32, 1209–1213. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gao, L.; Xu, D.M. Influence of Individual Endowment and Cognition on the Behavior of Farmers in Forestland Circulation: Based on the View of Intention-Behavior Consistency. Scientia Silvae Sinicae 2018, 54, 137–145. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Du, J.; Hu, Y.P.; Zhu, S.B. Impact of Eco-Forest Compensation Policy on Farmers’Career Differentiation in Collective Forest Regions: A Case Study of Jiangxi Province. Journal of Agro-Forestry Economics and Management 2021, 20, 749–758. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Ke, S.F.; Yang, G.H.; et al. The cognitions and willingness analysis of forestland management in the latter forest reform period: Based on the 200 household survey data in the Liaoning province. Forestry Economic Review 2015, 6, 98–105. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xie, F.T.; Zhu, S.B.; Du, J.; et al. The Influence of Location Factors and Forestland Endowments of Collective Forest Area on Households’ Choice of Management Modes. Issues of Forestry Economics 2018, 38, 1–6+97. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jin, L.J.; Xu, Q.L.; Yi, J.H.; et al. Integrating CVOR-GWLR-Circuit model into construction of ecological security pattern in Yunnan Province, China. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2022, 29, 81520–81545. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Li, Z. Constraints on Poverty Reduction Cooperation Under the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation Mechanism. China Quarterly of International Strategic Studies 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.H.; Do Thi, H.T.; Lin, Y.G.; et al. Forestry Poverty Reduction in the Framework of Mekong Cooperation Mechanism. World Forestry Research 2020, 33, 111–116. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yoddumnern-Attig, B.; Attig, G.A.; Santiphop, T.; et al. Population Dynamics and Community Forestry in Thailand. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sunderlin, W.D. Poverty alleviation through community forestry in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam: An assessment of the potential. Forest Policy and Economics 2006, 8, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhem, S.; Lee, Y.J.; Phin, S. Policy implications for community-managed forestry in Cambodia from experts’ assessments and case studies of community forestry practice. Journal of Mountain Science 2018, 15, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, M. The Tragedy of the Anticommons: A Concise Introduction and Lexicon. Social Science Electronic Publishing 2013, 76, 6–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberlack, C.; Tejada, L.; Messerli, P.; et al. Sustainable livelihoods in the global land rush? Archetypes of livelihood vulnerability and sustainability potentials. Global Environmental Change 2016, 41, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahad, S.; Nguyen-Thi-Lan, H.; Nguyen-Manh, D.; et al. Analyzing the status of multidimensional poverty of rural households by using sustainable livelihood framework: Policy implications for economic growth. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2022, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, G.S.; Qi, Y.N.; Zou, Y.Y. How Does Livelihood Capital Affect Forest Ecosystem Service Dependence? An Empirical Study Based on Micro Data of Workers in Northeast State-Owned Forest Areas. Scientific Decision Making 2023, 142–158. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sunderlin, W.D.; Angelsen, A.; Belcher, B.; Burgers, P.; Nasi, R.; Santoso, L.; Wunder, S. Livelihoods, forests, and conservation in developing countries: An Overview. World Development 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, N. Impact of Participatory Forestry Program on Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: Lessons from an Indian Province. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy 2012, 34, 428–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Cui, L.Z.; Lv, W.C.; et al. Exploring the frontiers of sustainable livelihoods research within grassland ecosystem: A scientometric analysis. Heliyon 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, L.; Ma, J. Research on the Influence of Herders on the Response Behavior of Grassland Ecological Compensation Policy. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2021, 693, 012117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisui, S.; Roy, S.; Bera, B.; et al. Economical and ecological realization of Joint Forest Management (JFM) for sustainable rural livelihood: A case study. Tropical Ecology 2022, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.Y.; Ahmed, T. Farmers’ Livelihood Capital and Its Impact on Sustainable Livelihood Strategies: Evidence from the Poverty-Stricken Areas of Southwest China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DFID. Sustainable Livelihoods Guidance Sheets. DFID; p. 2007.

- Zhang, X.R.; Gao, J.Z. An Empirical Analysis of the Utilization Efficiency of Farmers’ Collective Forest Land from the Perspective of Livelihood Capital. Journal of Northwest A&F University Social Science Edition 2020, 20, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, S.L.; Ma, Z. The interconnectedness between landowner knowledge, value, belief, attitude, and willingness to act: Policy implications for carbon sequestration on private rangelands. Journal of Environmental Management. 2014, 134, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartter, J.; Stevens, F.R.; Hamilton, L.C.; et al. Modelling Associations between Public Understanding, Engagement and Forest Conditions in the Inland Northwest, USA. PLoS ONE 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Zhan, T.T.; Yu, J.N.; et al. Determinants of rural households’ afforestation program participation: Evidence from China’s Ningxia and Sichuan provinces. Global Ecology and Conservation 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lp, A.; Xz, B.; Wt, A.; et al. Analysis of dispersed farmers’ willingness to grow grain and main influential factors based on the structural equation model. Journal of Rural Studies 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Ning, C.W.; Xie, F.T.; et al. Influence of rural labor migration behavior on the transfer of forestland. Natural Resource Modeling 2021, 34, e12293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Xiao, H.; Wang, Q.J.; et al. Study on Farmers’ Willingness to Maintain the Sloping Land Conversion Program in Ethnic Minority Areas under the Background of Subsidy Expiration. Forests 2022, 13, 1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.Y.; Zhang, T.Y.; Cao, J.; et al. Heterogeneity Impacts of Farmers’ Participation in Payment for Ecosystem Services Based on the Collective Action Framework. Land 2022, 11, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hujala, T.; Butler, B.J. Transformations towards a New Era in Small Scale Forestry: Introduction to the Small-Scale Forestry Special Issue. Small-Scale Forestry 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, R. Application of rural household survey to returned cropland to forest or grassland project: Application of rural household survey to returned cropland to forest or grassland project. Chinese Journal of Eco-Agriculture 2009, 16, 995–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oniki, S.; Berhe, M.; Negash, T.; et al. Do economic incentives crowd out motivation for communal land conservation in Ethiopia? Forest Policy and Economics 2023, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Xie, B.G.; Li, X.Q.; et al. Ecological compensation standards and compensation methods of public welfare forest protected area. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology 2016, 27, 1893–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.H.; Ding, D.H. Factors Influencing Farmers’ Willingness and Behaviors in Organic Agriculture Development: An Empirical Analysis Based on Survey Data of Farmers in Anhui Province. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.Y.; Zhou, X.H.; Tan, W.X.; et al. Analysis of dispersed farmers? willingness to grow grain and main influential factors based on the structural equation model. Journal of Rural Studies 2022, 93, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yu, W.J.; Liu, X.B.; et al. Analysis of Influencing Factors and Income Effect of Heterogeneous Agricultural Households’ Forestland Transfer. Land 2022, 11, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, R.; Yan, X. Analysis on the Supply Willingness of Mortgage Loan of Farmland Management Right under the Government-Led Mode in China Western’s Region. African and Asian Studies 2020, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, M.; Sendhil, R.; Chandel, B.S.; et al. Are Multidimensional Poor more Vulnerable to Climate change? Evidence from Rural Bihar, India. Social Indicators Research: An International and Interdisciplinary Journal for Quality-of-Life Measurement 2022, 162, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, J.H.; Roh, T.; Shin, S. Sustainable Assets and Strategies for Affecting the Income of Forestry Household: Empirical Evidence from South Korea. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wang, S.; Fu, B. Multilevel analysis of factors affecting participants’ land reconversion willingness after the Grain for Green Program. Ambio 2021, 50, 1394–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, T.; Berhane, T.; Mulatu, D.W.; et al. Willingness to accept compensation for afromontane forest ecosystems conservation. Land Use Policy 2021, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.X.; Li, H.; Yang, Y.; et al. Study on the Availability and Influencing Factors of Forestry Socialization Services for Farmers with Different Commercial Forest Management Types—Survey from Farmers in Zhejiang and Jiangxi Province. Forestry Economics 2019, 41, 79–88+96. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.J.; Xu, J.Q.; He, D.H.; et al. Households’ willingness to develop under-forest economy and its determinants in collective forest areas of Zhejiang. Journal of Zhejiang A&F University 2018, 35, 537–542. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).