Submitted:

02 June 2023

Posted:

05 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

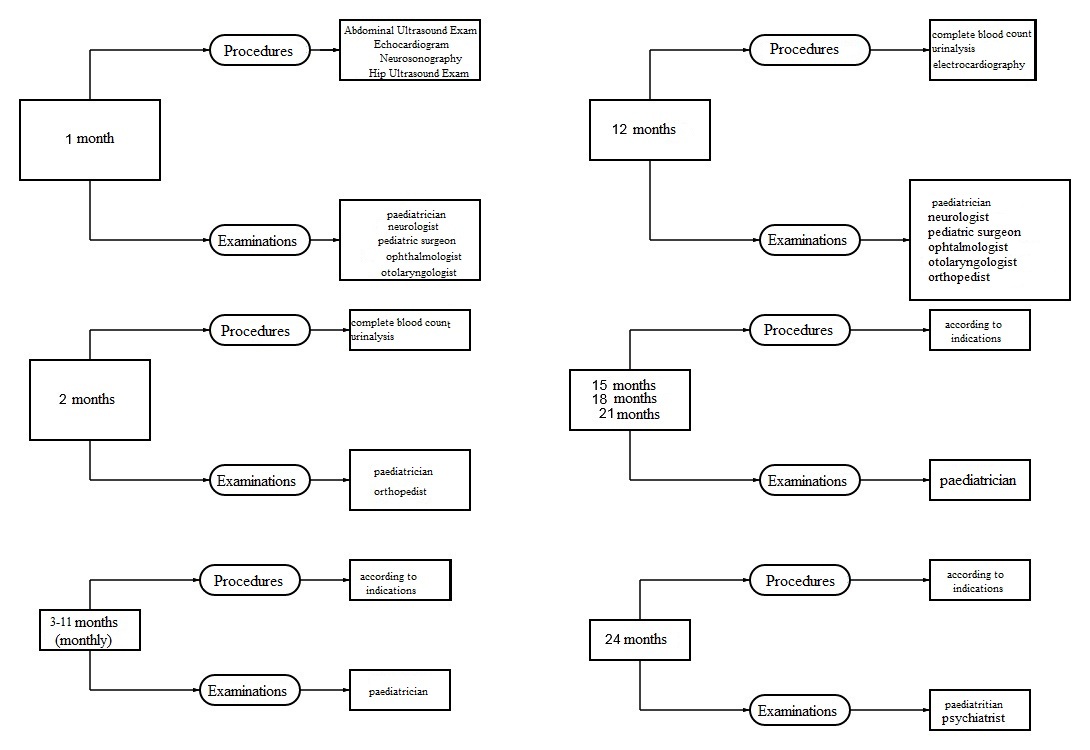

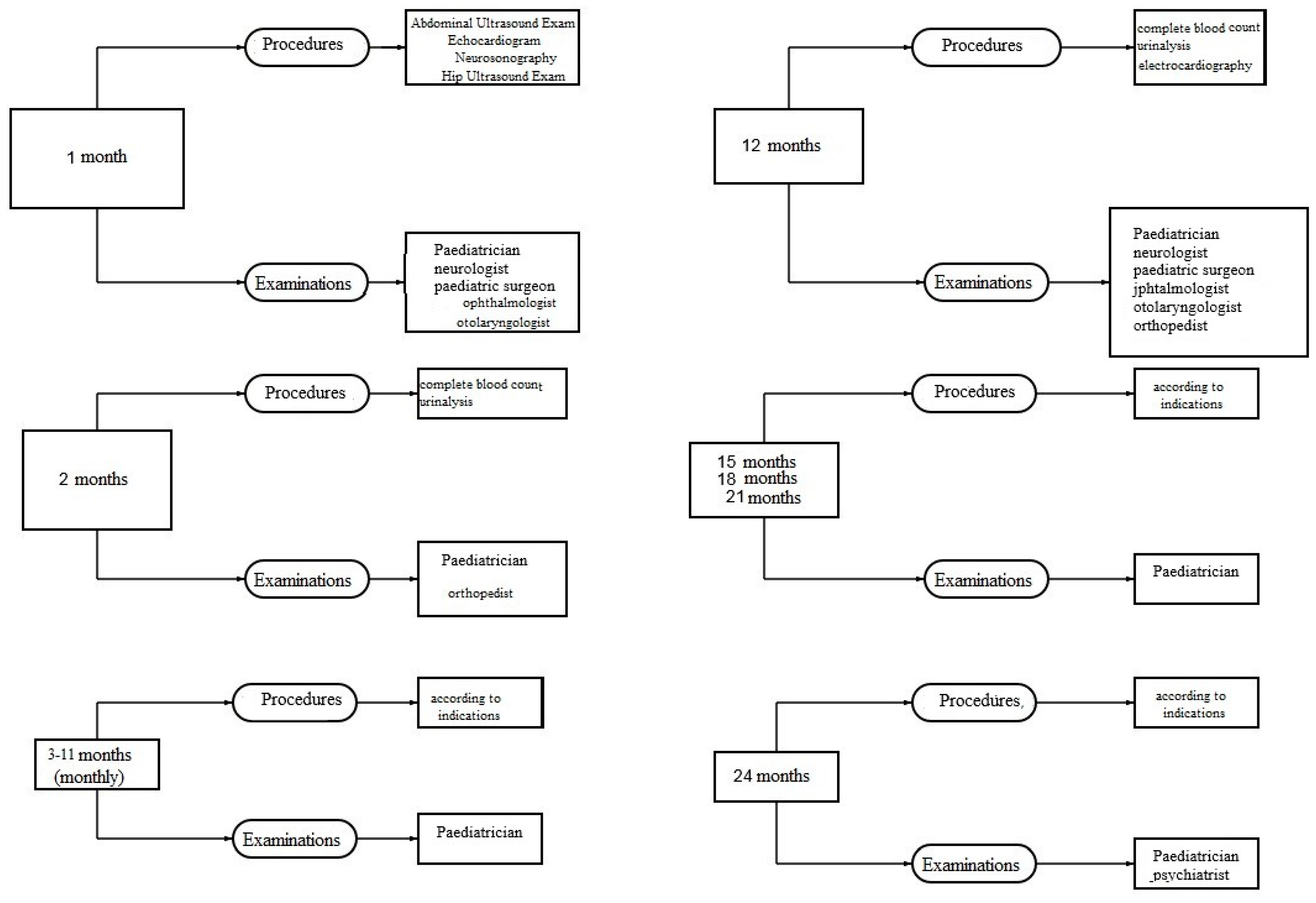

Materials and Methods

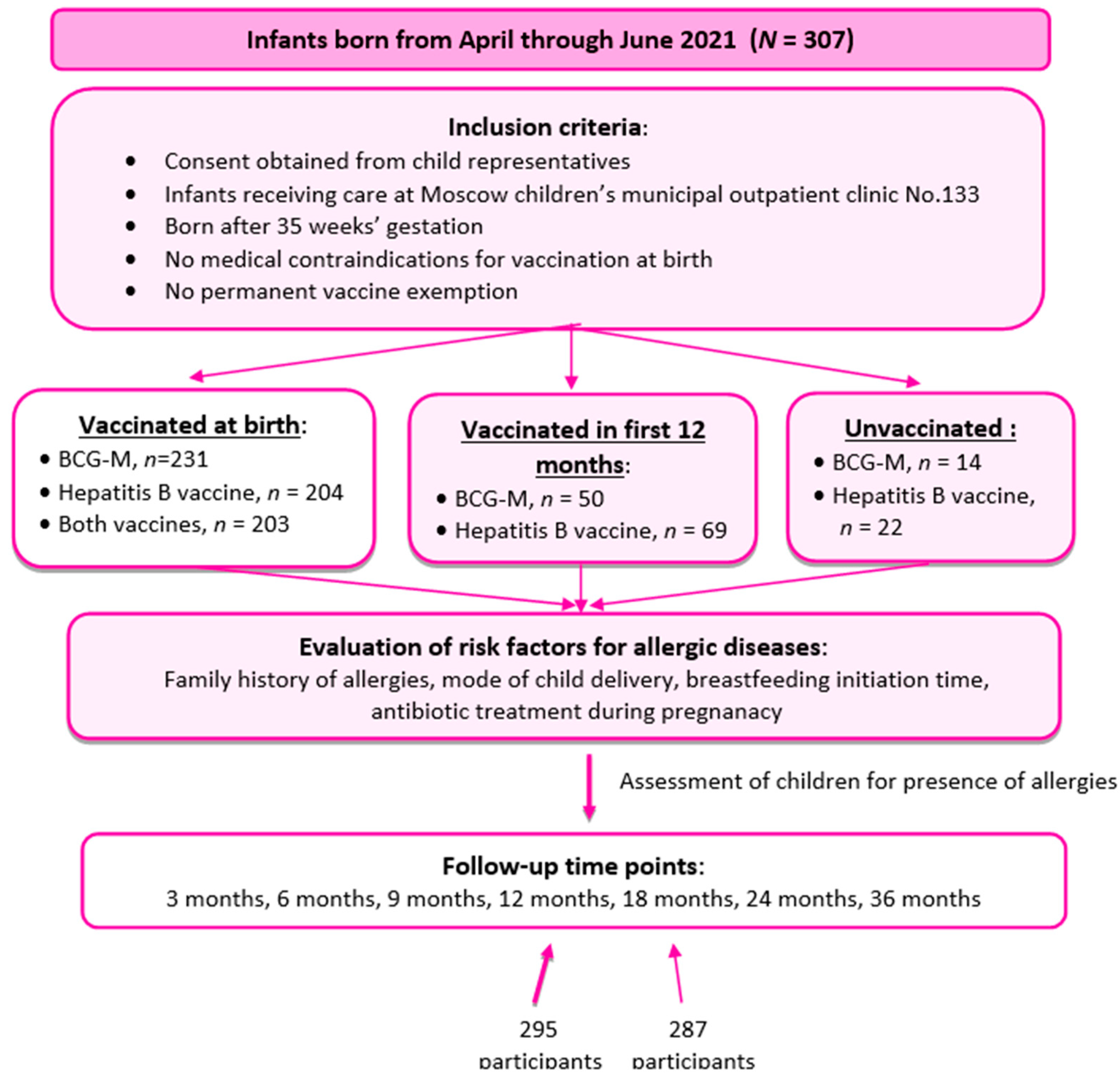

Participants and Data

- Vaccinated at birth (with BCG-M, hepatitis B vaccine or both). Vaccination was considered timely if it was performed within time limits specified in the National Immunization Schedule;

- Vaccinated in a catch-up mode in the first year of life (with BCG-M, hepatitis B vaccine or both);

- Unvaccinated in the first year of life.

- Cesarean birth;

- antibiotic treatment of the mother during pregnancy or antibiotic treatment of the neonate during first week of life;

- late breastfeeding initiation (more than 30 minutes after birth);

- allergic diseases in nearest relatives (a burdened family history).

Ethical Considerations

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria:

- consent obtained from parents or legal representatives;

- infants born from April through June 2021, residing in the area near Moscow children’s municipal outpatient clinic No.133 to which they are assigned and being permanently monitored at the said clinic;

- infants having no absolute medical contraindications for vaccination;

- infants having no reasonable temporary medical contraindications for vaccination at birth;

- infants born after 35 weeks’ gestation.

Exclusion criteria:

- change of health facility to which a child is assigned to;

- withdrawal of consent by the child’s representatives at any phase of the study.

Data Analysis and Statistics

Results

Discussion

- follow-up of children living in the same part of a big city and having similar social and living conditions;

- continuous health supervision of all children participating in the study starting from their birth which promotes active detection of early-onset disorders;

- uniform approach to organization and implementation of preventive vaccination and also to diagnosing AD;

- data on vaccination status is retrieved from electronic medical records which significantly minimizes the risk of data loss and the risk of getting wrong data.

Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- C. Avena-Woods. Overview of Atopic Dermatitis. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23:-S0.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 1. diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(2):338-351. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Ten great public health achievements--United States, 1900-1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999 Apr 2;48(12):241-3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). [PubMed]

- Ten great public health achievements--worldwide, 2001-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011 Jun 24;60(24):814-8. [PubMed]

- Anna, A. Minta et all. Progress Toward Regional Measles Elimination — Worldwide, 2000–2021. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2022;71(47):1489-1495.

- Wickens, K. , Crane J., Kemp T. et al. A case-control study of risk factors for asthma in New Zealand children. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2001; 25:44–49. 20. [CrossRef]

- Mullooly, JP. , Pearson J., Drew L. et al. Wheezing lower respiratory disease and vaccination of full-term infants. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2002; 11:21–30. [CrossRef]

- Henderson J, North K, Griffiths M, Harvey I, Golding J. Pertussis vaccination and wheezing illnesses in young children: prospective cohort study. The Longitudinal Study of Pregnancy and Childhood Team. BMJ. 1999; 318:1173–1176. [CrossRef]

- Nilsson L, Kjellman NI, Storsaeter J, Gustafsson L, Olin P. Lack of association between pertussis vaccination and symptoms of asthma and allergy. JAMA. 1996; 275:760. 23. [CrossRef]

- Nilsson L, Kjellman NI, Bjorksten B. A randomized controlled trial of the effect of pertussis vaccines on atopic disease. Arch PediatrAdolesc Med. 1998;152: 734–738. 7: 1998;152.

- Strachan, DP. Family size, infection and atopy: the first decade of the “hygiene hypothesis”. Thorax. 2000 Aug;55 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S2-10. PMID: 10943631; PMCID: PMC1765943. [CrossRef]

- Umetsu DT, McIntire JJ, Akbari O, Macaubas C, DeKruyff RH. Asthma: an epidemic of dysregulated immunity. Nat Immunol. 2002 Aug;3(8):715-20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matheson MC, Haydn Walters E, Burgess JA. et al. Childhood immunization and atopic disease into middle-age--a prospective cohort study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010 Mar; 21(2 Pt 1):301-6. Epub 2009 Dec 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prikaz MZ RF ot 06.12.2021 №1122n «Ob utverzhdenii natsionalnogo kalendarya profilakticheskikh provivok i kalendarya profilakticheskikh provivok po epidemicheskim pokazaniyam».

- Chen, J., Gao, L., Wu, X. et al. BCG-induced trained immunity: history, mechanisms and potential applications. J TranslMed 21, 106 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Moorlag SJCFM, Rodriguez-Rosales YA, Gillard J. et al. BCG Vaccination Induces Long-Term Functional Reprogramming of Human Neutrophils. Cell Rep. 2020 Nov 17;33(7):108387. PMID: 33207187; PMCID: PMC7672522. [CrossRef]

- Escobar LE, Molina-Cruz A, Barillas-Mury C. BCG vaccine protection from severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). PNAS. 2020; 117(30):17720–17726. [CrossRef]

- Miller A, Reandelar M-J, Fasciglione K, et al. Correlation between universal BCG vaccination policy and reduced morbidity and mortality for COVID-19: an epidemiological study. medRxiv. Preprint March 2020. [CrossRef]

- Hegarty P-K, Kamat A, Zafirakis H, DiNardo A. BCG vaccination may be protective against COVID-19. PreprintMarch 2020. 20 March. [CrossRef]

- Sala G., Miyakawa T. Association of BCG vaccination policy with prevalence and mortality of COVID-19. medRxiv. Preprint May 2020. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- Shet A, Ray D, Malavige N, et al. Differential COVID-19-attributable mortality and BCG vaccine use in countries. medRxiv. Preprint April 2020. 20 April. [CrossRef]

- Berg MK, Yu Q, Salvador CE, et al. Mandated BCG vaccination predicts flattened curves for the spread of COVID-19. medRxiv.Preprint April 2020. 20 April. [CrossRef]

- Untersmayr E., Bax HJ., Bergmann C. et al. AllergoOncology: Microbiota in allergy and cancer - A European Academy for Allergy and Clinical Immunology position paper. Allergy. 2019 Jun;74(6):1037-1051. Epub 2019 Mar 6. PMCID: PMC6563061. [CrossRef]

- Kiwako Yamamoto-Hanada et al. Influence of antibiotic use in early childhood on asthma and allergic diseases at age 5. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 119 (2017) 54-58.

- Hadi HA, Tarmizi AI, Khalid KA, Gajdács M, Aslam A, Jamshed S. The Epidemiology and Global Burden of Atopic Dermatitis: A Narrative Review. Life (Basel). 2021 Sep 9;11(9):936. PMID: 34575085; PMCID: PMC8470589. [CrossRef]

- Wollenberg A., Barbarot S., Bieber T. et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(5): 657–682. [CrossRef]

- Klinicheskiye recommendatsii «Atopichesky dermatit», odobrenniye Nauchno-prakticheskim sovetom Minzdrava Rossii. 2021.

- Kubanov A.A., Bogdanova E.V. Organizatsiya i rezultaty okazaniya meditsinskoi pomoschi po profilyu “dermatovenerologhiya” v Rossiiskoi Federatsii. Itoghi 2018 goda. Vestnik dermatologhii I venerologhii. 2019; 95(4):8–23. [CrossRef]

- Pittet LF, Messina NL, et al. Prevention of infant eczema by neonatal Bacillus Calmette-Guérin vaccination: The MIS BAIR randomized controlled trial. Allergy. 2022 Mar;77(3):956-965. Epub 2021 Aug 9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thøstesen LM, Kjaergaard J, et al. Neonatal BCG vaccination and atopic dermatitis before 13 months of age: A randomized clinical trial. Allergy. 2018 Feb;73(2):498-504. Epub 2017 Oct 9. [CrossRef]

- Farooqi IS, Hopkin JM. Early childhood infection and atopic disorder. Thorax. 1998;53:927–932.

- Shurmipa IA., Meshkova RYa., Sazonenkova LV. Rol’ sistemy tsitokinov u patsientov s allergopatologiei, privitykh rekombinantnymi vaktsinami protiv gepatita B. Mir virusnykh gepatitov. 2005; (11):5–6. (In Russ).33. Zhao K, Miles P, Hubbard R, et al. Bacille Calmette Guerin Vaccination in Early Childhood and Risk of Allergic Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of data from 13 large scale studies. Authorea. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Navaratna S, EstcourtM J, Burgess J, et al. Childhood vaccination and allergy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy. 2021;76(7):2135–2152. [CrossRef]

- Kemp T, Pearce N, Fitzharris P, et al. Is infant immunization a risk factor for childhood asthma or allergy? Epidemiology. 1997;8:678–680.

- Kiraly N, Koplin JJ, Crawford NW, Bannister S, Flanagan KL, Holt PG, et al. Timing of routine infant vaccinations and risk of food allergy and eczema at one year of age. Allergy. 2016;71:541–9. [CrossRef]

- Arnoldussen DL, Linehan M, Sheikh A. BCG vaccination and allergy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011 Jan;127(1):246-53, 253.e1-21. Epub 2010 Oct 8. PMID: 20933258. [CrossRef]

- Mary F. Linehan et al. Does BCG vaccination protect against childhood asthma? Final results from the Manchester Community Asthma Study retrospective cohort study and updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:688-95. [CrossRef]

- Thøstesen LM, Kjaer HF, Pihl GT, Nissen TN, Birk NM, Kjaergaard J, Jensen AKG, Aaby P, Olesen AW, Stensballe LG, Jeppesen DL, Benn CS, Kofoed PE. Neonatal BCG has no effect on allergic sensitization and suspected food allergy until 13 months. PediatrAllergyImmunol. 2017 Sep;28(6):588-596. [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto-Hanada et al. Cumulative inactivated vaccine exposure and allergy development among children: a birth cohort from Japan. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine. 2020; 25:27. [CrossRef]

| Number of subjects (absolute / %) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Boys / Girls | 155/140 | 52.5%/47.5% |

| Having risk factors for development of AD | 93 | 31.5% |

| BCG-М given at the maternity hospital | 231 | 78.3% |

| Hepatitis B vaccine (V1, or 1st dose) given at the maternity hospital | 204 | 69.2% |

| Both vaccines given at the maternity hospital | 203 | 68.8% |

| BCG-М given in the first year of life | 50 | 16.9% |

| Hepatitis B vaccine (V1, or 1st dose) given in the first year of life | 69 | 23.3% |

| BCG-М unvaccinated | 14 | 4.7% |

| Hepatitis B (V1, or 1st dose) unvaccinated | 22 | 7.5% |

| Onset of AD before 12 months of age (and percentage of infants with risk factors) |

73 (34) | 24.7% (46.6%) |

| Onset of AD between 12 and 18 months of age (and percentage of infants with risk factors) | 20 (20) | 6.8% (100%) |

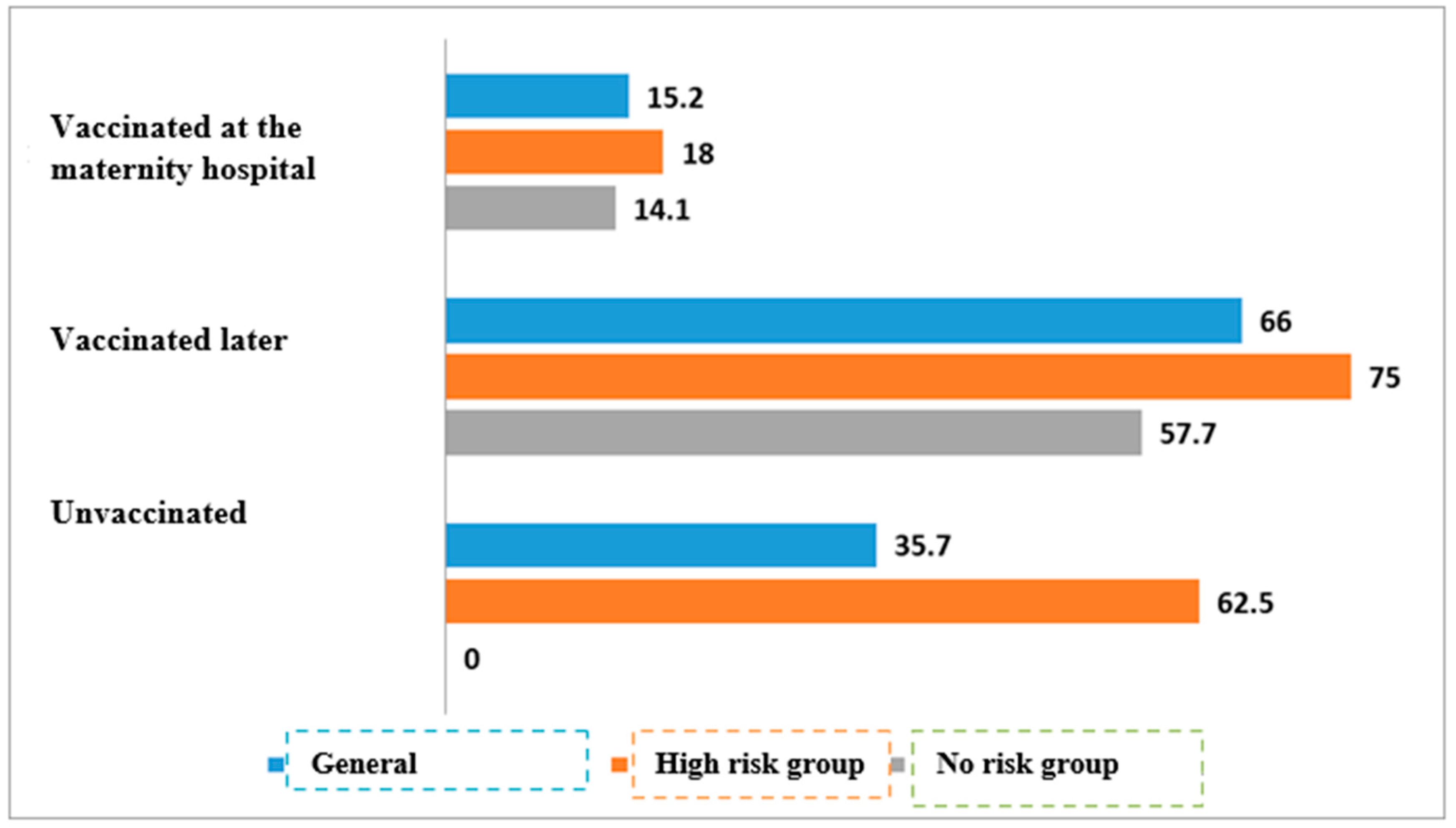

| 2А. TB vaccination | ||||||

| TB vaccination status, all infants | Аtopic dermatitis | P-value | ||||

| With AD (n/%) | Without AD (n/%) | |||||

| Vaccinated at the maternity hospital | 35/231 | 15.2% | 196/231 | 84.8% | <0.01 | |

| Vaccinated later | 33/50 | 66% | 17/50 | 34% | ||

| Unvaccinated | 5/14 | 35.7% | 9/14 | 64.3% | ||

| TB vaccination status, infants with risk for allergic diseases | Atopic dermatitis | P-value | ||||

| With AD (n/%) | Without AD (n/%) | |||||

| Vaccinated at the maternity hospital | 11/61 | 18% | 50/61 | 82% | <0.01 | |

| Vaccinated later | 18/24 | 75% | 6/24 | 25% | ||

| Unvaccinated | 5/8 | 62.5% | 3/8 | 37.5% | ||

| TB vaccination status, infants with no risk for allergic diseases | Atopic dermatitis | P-value | ||||

| With AD (n/%) | Without AD (n/%) | |||||

| Vaccinated at the maternity hospital | 24/170 | 14.1% | 146/170 | 85.9% | * | |

| Vaccinated later | 15/26 | 57.7% | 11/26 | 42.3% | ||

| Unvaccinated | 0/6 | 0% | 6/6 | 100% | ||

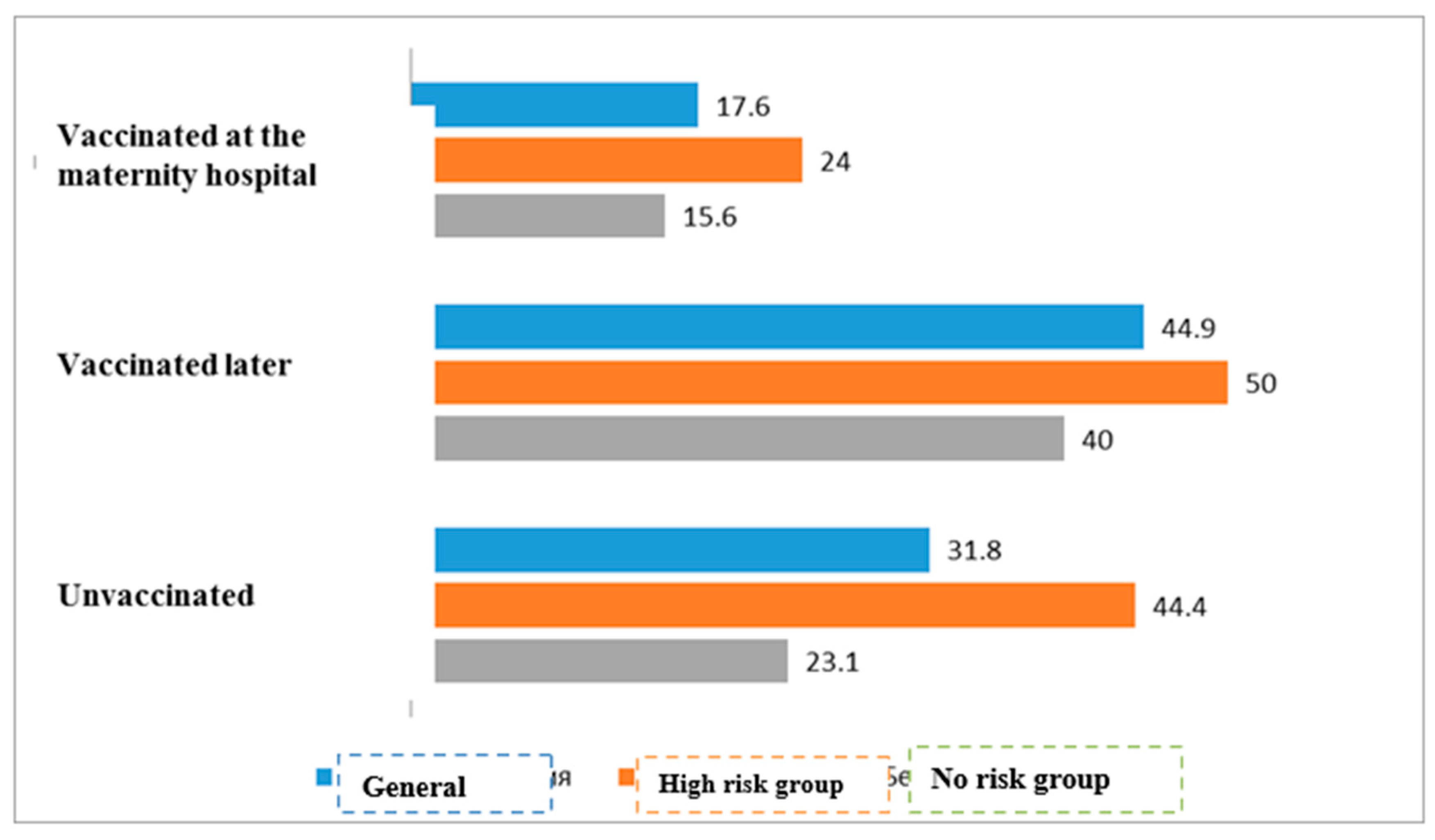

| 2В. Hepatitis B vaccination | ||||||

| Hepatitis B vaccination status, all infants | Atopic dermatitis | P-value | ||||

| With AD (n/%) | Without AD (n/%) | |||||

| Vaccinated at the maternity hospital | 36/204 | 17.6% | 168/204 | 82.4% | 0.043 | |

| Vaccinated later | 31/69 | 44.9% | 38/69 | 55.1% | ||

| Unvaccinated | 7/22 | 31.8% | 15/22 | 68.2% | ||

| Hepatitis B vaccination status, infants with risk of allergic diseases | Atopic dermatitis | P-value | ||||

| With AD (n/%) | Without AD (n/%) | |||||

| Vaccinated at the maternity hospital | 12/50 | 24.0% | 38/50 | 76.0% | <0.01 | |

| Vaccinated later | 17/34 | 50.0% | 17/34 | 50.0% | ||

| Unvaccinated | 4/9 | 44.4% | 5/9 | 55.6% | ||

| Hepatitis B vaccination status, infants with no risk for allergic diseases | Atopic dermatitis | P-value | ||||

| With AD (n/%) | Without AD (n/%) | |||||

| Vaccinated at the maternity hospital | 24/154 | 15.6% | 130/154 | 84.4% | * | |

| Vaccinated later | 14/35 | 400% | 21/35 | 60.0% | ||

| Unvaccinated | 3/13 | 23.1% | 10/13 | 76.9% | ||

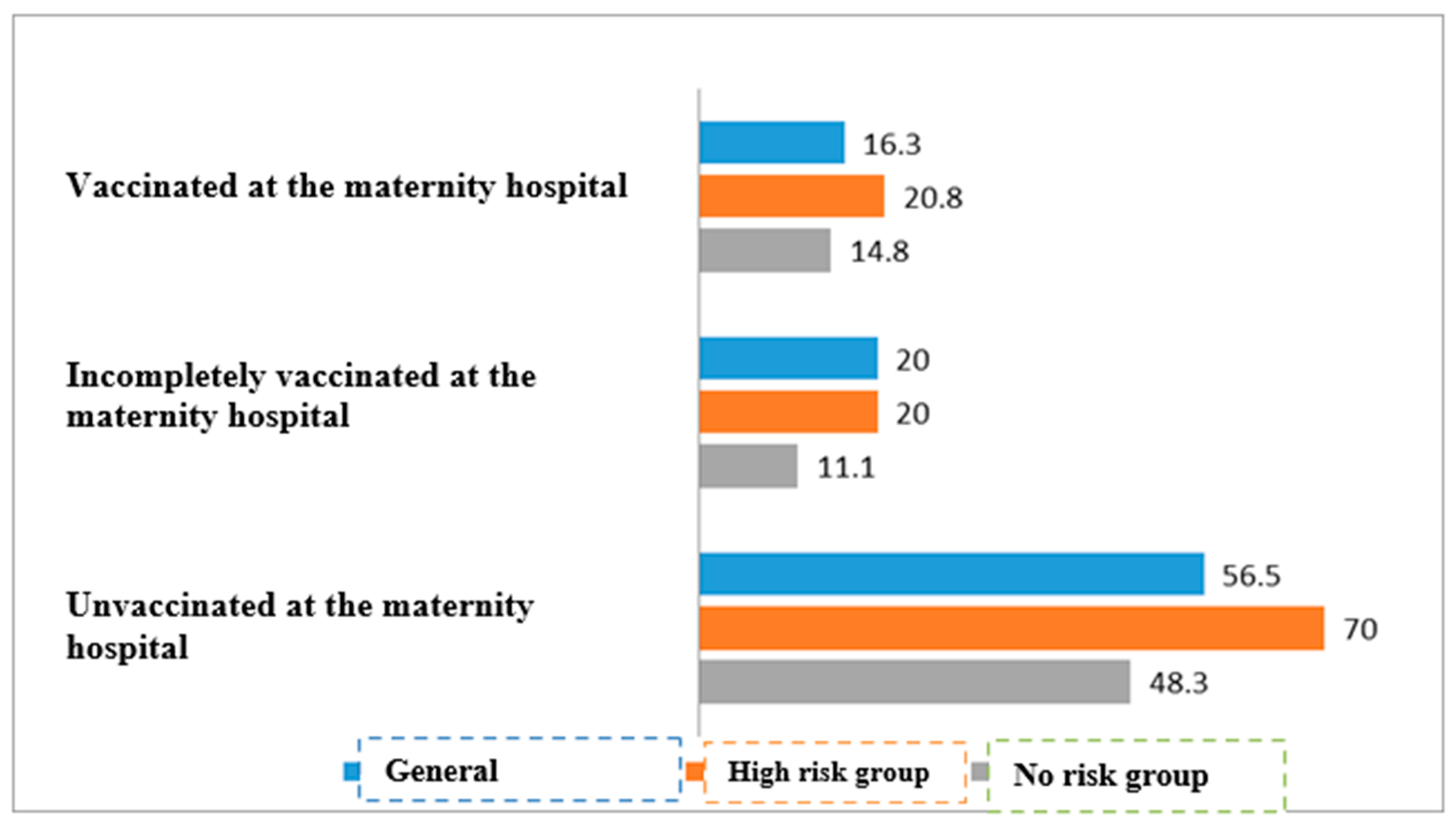

| 2С. TB and hepatitis B vaccination | ||||||

| TB and hepatitis B vaccination status, all infants | Atopic dermatitis | P-value | ||||

| With AD (n/%) | Without AD (n/%) | |||||

| Both vaccines given in maternity hospital | 33/203 | 16.3% | 170/203 | 83.7% | <0.01 | |

| At least one vaccine given in maternity hospital | 6/30 | 20.0 % | 24/30 | 80.0% | ||

| No vaccination available in maternity hospital | 35/62 | 56.5% | 27/62 | 43.5% | ||

| Tb and hepatitis B vaccination status, infants with risk for allergic diseases | Atopic dermatitis | P-value | ||||

| With AD (n/%) | Without AD (n/%) | |||||

| Both vaccines given in maternity hospital | 10/48 | 20.8% | 38/48 | 79.2% | <0.01 | |

| At least one vaccine given in maternity hospital | 3/15 | 20.0% | 11/15 | 80.0% | ||

| No vaccination available in maternity hospital | 21/30 | 70.0%% | 9/30 | 30.0% | ||

| TB and hepatitis B vaccination status, infants with no risk for allergic diseases | Atopic dermatitis | P-value | ||||

| With AD (n/%) | Without AD (n/%) | |||||

| Both vaccines given in maternity hospital | 23/155 | 14.8% | 132/155 | 85.2% | <0.01 | |

| At least one vaccine given in maternity hospital | 2/18 | 11.1% | 16/18 | 88.9% | ||

| No vaccination available in maternity hospital | 14/29 | 48.3% | 15/29 | 51.7% | ||

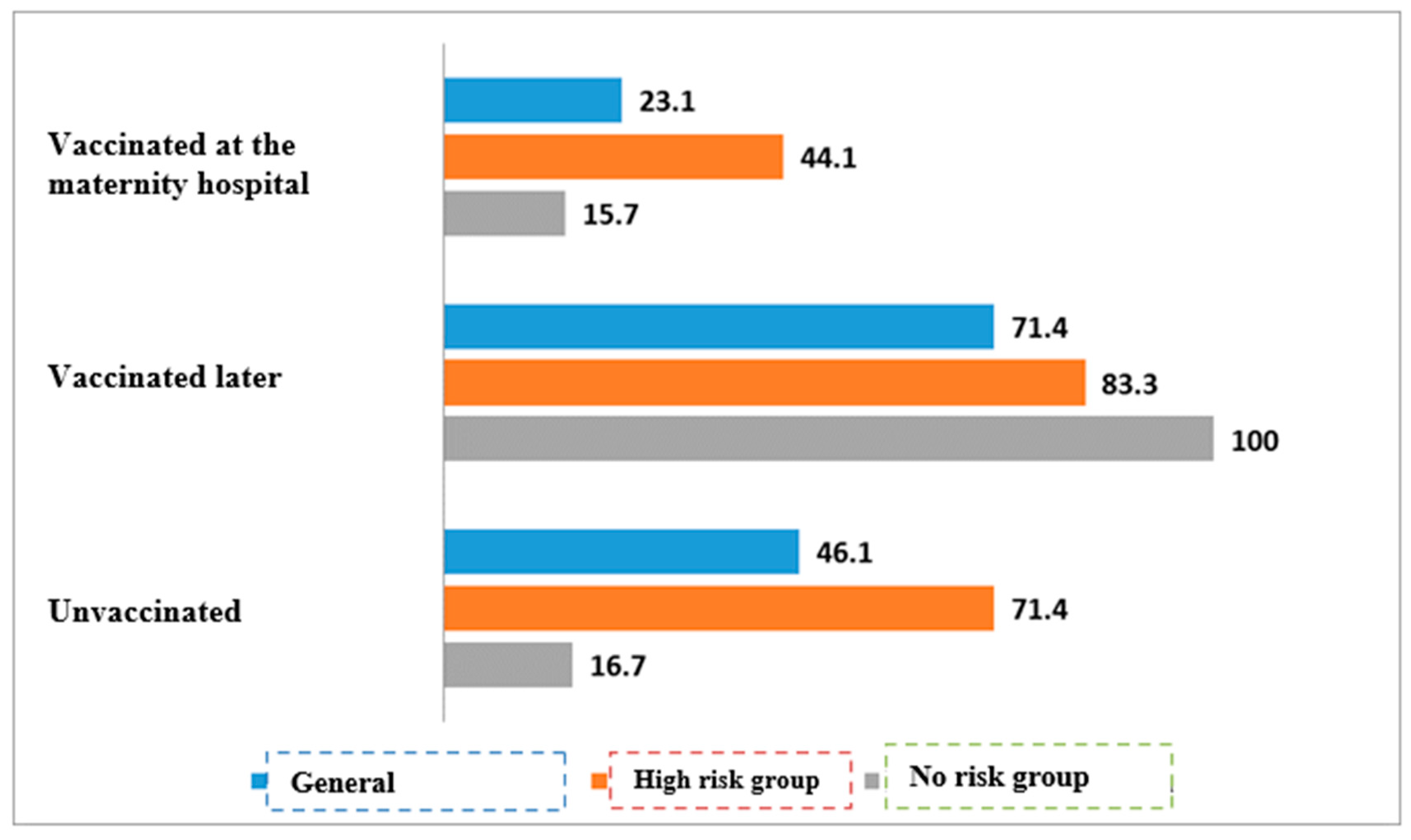

| 3А. Tuberculosis vaccination | ||||||

|

TB vaccination status, all infants |

Atopic dermatitis | P-value | ||||

| With AD (n/%) | Without AD (n/%) | |||||

| Vaccinated at the maternity hospital | 52/225 | 23.1% | 173/225 | 76.9% | <0.01 | |

| Vaccinated later | 35/49 | 71.4% | 14/49 | 28.6% | ||

| Unvaccinated | 6/13 | 46.2% | 7/13 | 53.8% | ||

| TB vaccination status, infants with risk of allergic diseases | Atopic dermatitis | P-value | ||||

| With AD (n/%) | Without AD (n/%) | |||||

| Vaccinated at the maternity hospital | 26/59 | 44.1% | 33/59 | 55.9% | <0.01 | |

| Vaccinated later | 20/24 | 83.3% | 4/24 | 16.7% | ||

| Unvaccinated | 5/7 | 71.4% | 2/7 | 28.6% | ||

| TB vaccination status, infants with no risk of allergic diseases | Atopic dermatitis | P-value | ||||

| With AD (n/%) | Without AD (n/%) | |||||

| Vaccinated at the maternity hospital | 26/166 | 15.7% | 140/166 | 84.3% | * | |

| Vaccinated later | 15/15 | 100,0% | 0/15 | 0% | ||

| Unvaccinated | 1/6 | 16.7% | 5/6 | 83.3% | ||

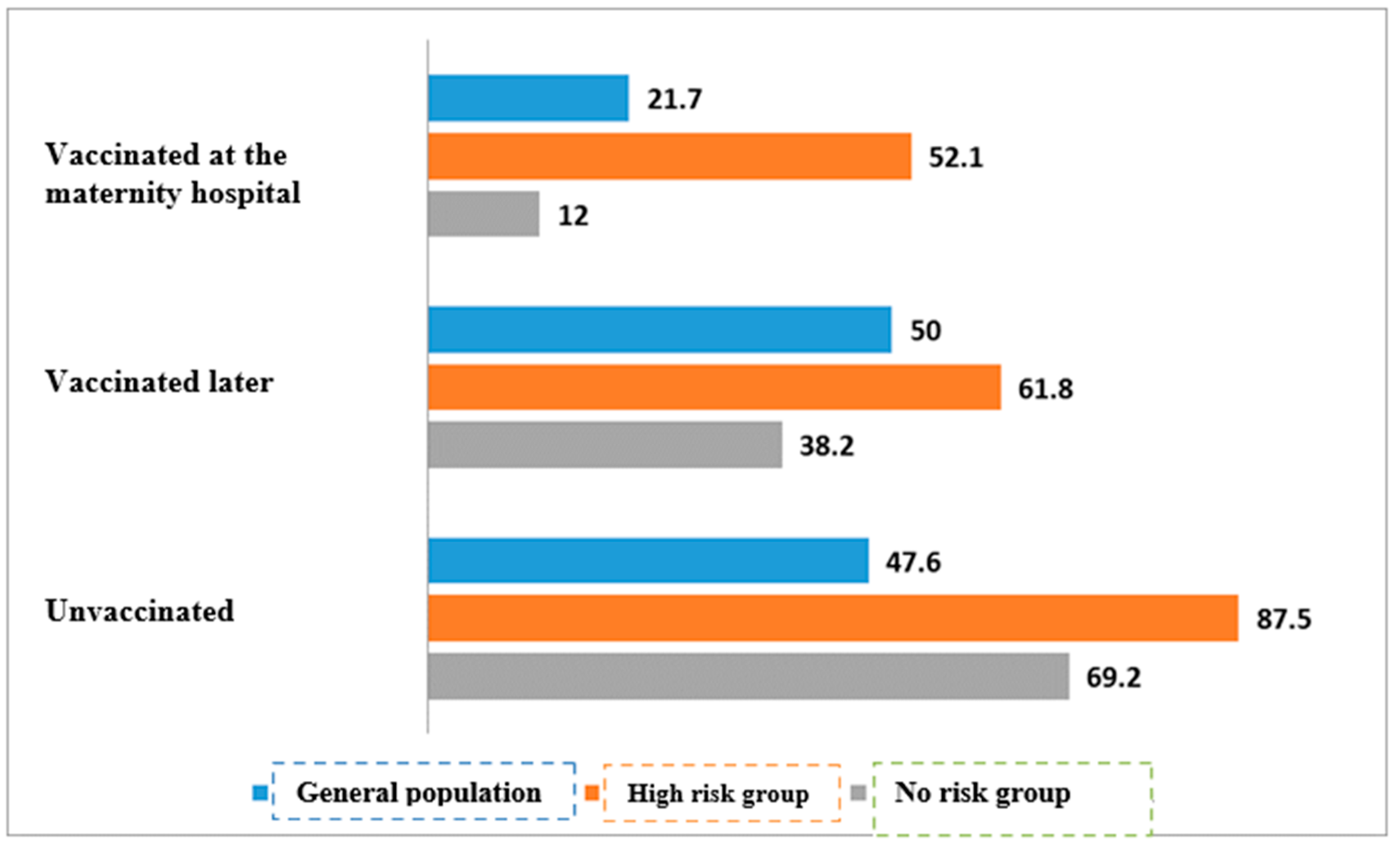

| 3В. Hepatitis B vaccination | ||||||

| Hepatitis B vaccination status, all infants | Atopic dermatitis | P-value | ||||

| With AD (n/%) | Without AD (n/%) | |||||

| Vaccinated at the maternity hospital | 43/198 | 21.7% | 155/198 | 78.3% | <0.01 | |

| Vaccinated later | 34/68 | 50.0% | 34/68 | 50.0% | ||

| Unvaccinated | 10/21 | 47.6% | 11/21 | 52.4% | ||

| Hepatitis B vaccination status, infants with risk of allergic diseases | Atopic dermatitis | P-value | ||||

| With AD (n/%) | Without AD (n/%) | |||||

| Vaccinated at the maternity hospital | 25/48 | 52.1% | 23/48 | 47.9% | * | |

| Vaccinated later | 21/34 | 61.8% | 13/34 | 38.2% | ||

| Unvaccinated | 7/8 | 87.5% | 1/8 | 12.5% | ||

| Hepatitis B vaccination status, infants with no risk of allergic diseases | Atopic dermatitis | P-value | ||||

| With AD (n/%) | Without AD (n/%) | |||||

| Vaccinated at the maternity hospital | 18/150 | 12.0% | 132/150 | 88.0% | <0.01 | |

| Vaccinated later | 13/34 | 38.2% | 21/34 | 61.8% | ||

| Unvaccinated | 9/13 | 69.2% | 4/13 | 30.8% | ||

| 3С. TB and hepatitis B vaccination | ||||||

| TB and hepatitis B vaccination status, all infants | Atopic dermatitis | P-value | ||||

| With AD (n/%) | Without AD (n/%) | |||||

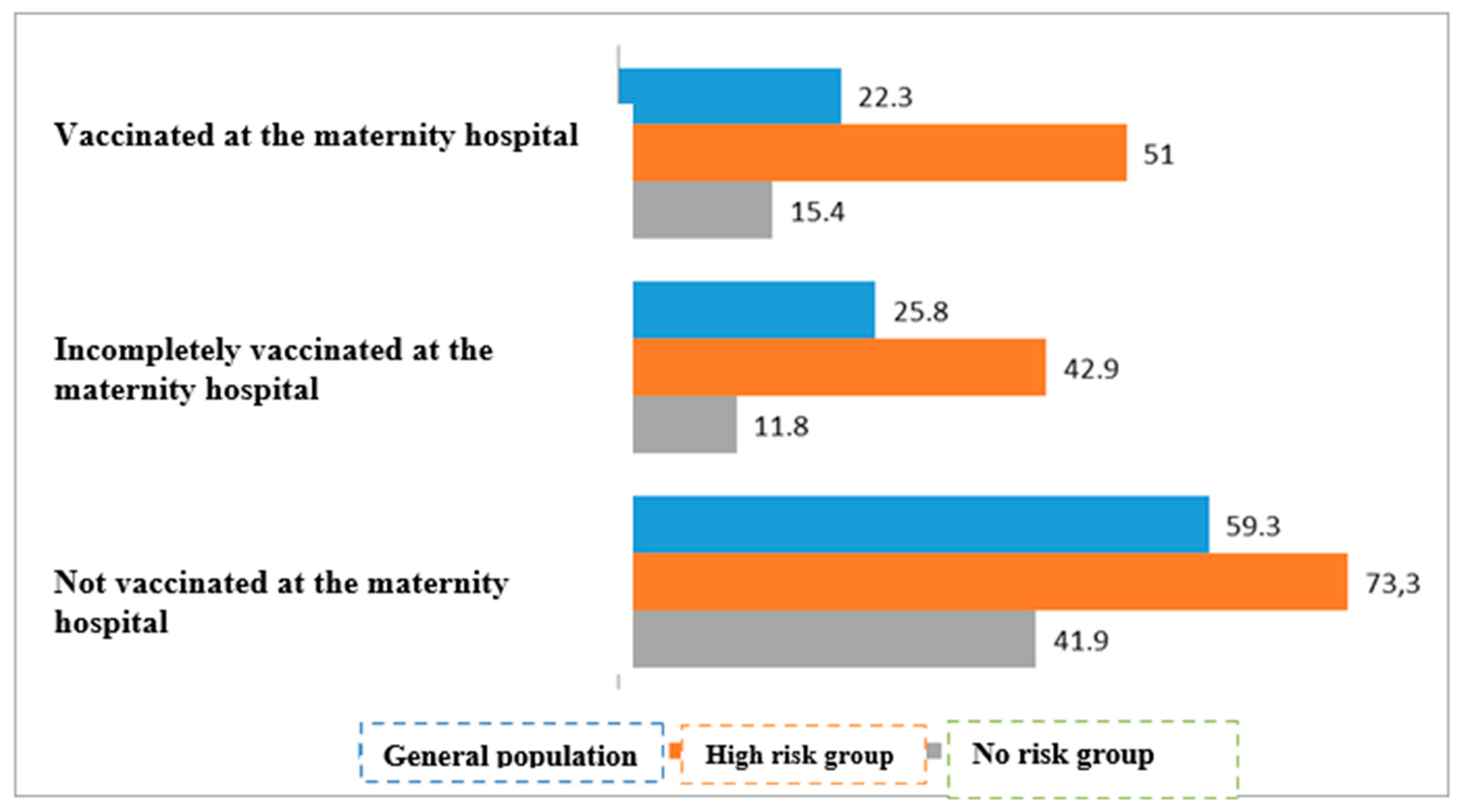

| Both vaccines given in maternity hospital | 44/197 | 22.3% | 153/197 | 77.7% | <0.01 | |

| At least one vaccine given in maternity hospital | 8/31 | 25.8% | 23/31 | 74.2% | ||

| No vaccination available in maternity hospital | 35/59 | 59.3% | 24/59 | 40.7% | ||

| TB and hepatitis B vaccination status, infants with risk of allergic diseases | Atopic dermatitis | P-value | ||||

| With AD (n/%) | Without AD (n/%) | |||||

| Both vaccines given in maternity hospital | 25/49 | 51.0% | 24/49 | 49.0% | <0.01 | |

| At least one vaccine given in maternity hospital | 6/14 | 42.9% | 8/14 | 57.1% | ||

| No vaccination available in maternity hospital | 22/30 | 73.3% | 8/30 | 26.7% | ||

| TB and hepatitis B vaccination status, infants with no risk of allergic diseases | Atopic dermatitis | P-value | ||||

| With AD (n/%) | Without AD (n/%) | |||||

| Both vaccines given in maternity hospital | 23/149 | 15.4% | 126/149 | 84.6% | <0.01 | |

| At least one vaccine given in maternity hospital | 2/17 | 11.8% | 15/17 | 88.2% | ||

| No vaccination available in maternity hospital | 13/31 | 41.9% | 18/31 | 58/1% | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).