Abstract The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) is known for its high car ownership and usage as well its high GDP per capita. This is combined with low/ or no provision of public transportation (PT) systems, has been resulting in perceptual attitudes of full dependency on private car travel. The level of awareness of the benefits of reducing car use and increasing the travel by more sustainable options, has a great impact on social change and behaviour. The Kingdom is currently progressing towards a new phase of “national transfer” through implementation of strategic and sustainable measures and programs. The city of Riyadh is construction a massive metro-system in Riyadh, that is nearing completion and operation. The public is aware of the national agenda, aware of the newly constructed projects and aware of the needed social change to realize the new vision of the country. This paper aims to assess travel behaviour and attitudes towards public transportation of Saudi travellers’ who are witnessing the new transformation in the Kingdom and who are aware of the new sustainable projects. Depicted from the theory of random utility, a discrete choice model of the intent to use public transportation is calibrated as a function of social and attitudinal factors. An online survey was designed and carried out using social media means; a completed 399 questionnaires have been obtained and studied. The methodology includes examining attitudes and preferences of the participants towards using public transportation options against participants’ socio-economic data. The analysis was carried out using ordinal logistic regression analysis (OLR) which is an efficient technique that is derived from the theory of random utility. The results show a good support for PT; a higher support for public transportation modes, form participants who are young females, lower income groups and the university graduates were reported. The level of support seems higher with the higher level of awareness about the new PT system.

1. Introduction

Travel attitudes in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) have become centred on the private car. This is a result of the very high car ownership and usage in the country, the high GDP per capita and the low or non-provision of public transportation options. There are very limited bus services in most KSA cities, and they are mostly used by the very low-income classes of the expatriates. In addition, in most Saudi cities, riding public transportation is culturally not adequate while car travel has become the normal travel option. Even the low-income Saudi families who do not own private cars, rely on contracted drivers or taxis for their travel rather than using public transportation. This is a major phenomenon that needs further consideration, given the KSA population, size and the national vision 2030.

For example, Riyadh city is situated in the centre of the Eastern part of the Najd hill and is the largest city of Saudi Arabia. There are 13 municipalities that house 209 districts that are accommodated within a 40-mile span of Riyadh [

1]. Riyadh’s population increased rapidly from 40,000 inhabitants in 1935 and 83,000 in 1949 to a total of 7.6 million inhabitant in the year 2019, making it the most- populated city in the KSA [

1,

2]. Of the current population, there is about 64.19% are Saudis, while the expatriates account for 35.81%. The female population accounts for over 43% of the total population with population density of 2379 inhabitants per square kilometre (ADA 2015). About 85% of the eight million daily trips are carried out by private cars whereas just 2% of the trips are undertaken by buses [

2,

3,

4]. Between 1996 and 2018, private vehicle ownership has increased by over 200%. Until recently, the vast majority of Riyadh population have never used public transportation, instead they completely rely on private cars in all their travel. Any world city of that size, population and volume of travel would most likely be operating a mass transit system; however, Riyadh city does not yet. The current Riyadh public transportation system consists of buses that are operated by the Saudi Public Transport authorities [

2,

3,

4]. These started operation in 1979 aiming to run high-level bus services locally and across neighbouring countries such as the Arab Gulf countries, Jordan, Turkey and Syria.

Compared to other neighbouring cities such as Dubai, Doha, or Kuwait, where there are more people support and use for the public transportation systems that are in operation, KSA is still behind. Although public transportation systems in those countries are also largely used by the expatriates who are familiar with and accustomed to using them, this is not a major issue there as majority of the population are expatriates and there is a good use of the public transportation system. KSA is a much bigger country however, with a much larger population and a much larger Saudi percentage of the population (e.g. about 65% of the city of Riyadh’s population are Saudi nationals). It is very important therefore, to encourage the Saudi nationals to accept the public transportation options and use them. It is hence, very important to evaluate the willingness of the Saudi nationals to use public transportation systems and to assess their level of support.

With the new national vision 2030, the city of Riyadh is constructing a number of public transportation options including a substantial metro system, costing a massive $22.5 billion, to encourage more sustainable travel patterns. The local population are aware of the newly constructed public transportation options through the construction work and delays. They are also aware of the proposed routes and conscious about possibilities of their use.

All the above developments are expected to result in changes in the Saudi’s social travel behaviour and attitudes towards the usage of public transportation systems; whilst public transportation modes of transport were not adequate nor acceptable in the past for Saudi nationals to use, it is hoped that the new era will improve the situation and encourage a shift towards more sustainable options of travel. Without a real social change, the newly constructed system could well deteriorate, the level of service decline and the newly built metro system become an infrastructure burden and a waste of investment in the city.

Social change occurs because of changes in population volumes, population composition, culture and technology, awareness about benefits or disbenefits, and environmental and natural changes. In the case of Saudi Arabia, social change is happening as a result of advancements in industrial and environmental technologies, higher awareness of the population of the benefits of the more sustainable options, and the growing population exposure to other societies and communities. In this paper, we attempt to assess the overall impact of changes in attitudes and behaviour towards travel choices in the city of Riyadh.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2. is overviewing relevant previous literature on modal choice models, travel choice studies, previous studies on travel behaviour, and attitudes in Riyadh and other neighbouring cities/ countries. The methodology is presented in

Section 3, including the experimental design and the ordered logistic regression model). General data statistics are presented in Chapter 4 and analysis of the survey results using ordered logistic regression is presented in

Section 5. The conclusions from the study are presented in

Section 6 while limitations are presented in

Section 7.

Previous Literature

Modal choice modelling and choices between public transport and private transport are very relevant and influential part for the understanding and prediction of future travel behaviour [

5,

6,

7]. Theories of social science have also been developed and used heavily to understand and assess travel behaviour [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. There are many studies in transportation planning processes that applied both travel behavioural and social science theories [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. In traditional modal split studies, the market would be divided mainly between private and public modes of travel. These models were presented as diversion curves that were essentially created on the basis of one or two characters of the trips that dominated the generalized cost functions of the choice models (eg. in vehicle travel time or cost) [

20,

21,

22]. Essentially, S-shaped curves, appear to characterise the relationship between the cost difference and the proportion of trips made by each option [

23,

24].

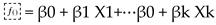

Figure 1 shows a typical S-shaped curve representation of the split and cost difference between two options (1&2). The components of the cost difference between the two options have been developed since to include qualitative and quantitative level of service factors, social, and attitudes and behavioural factors.

As

Figure 1 shows, most travellers have a choice between the two options (say PT and private travel options), with various levels of cost difference. In these cases, travellers assess the available travel options based on the level of service including travel time, travel cost, comfort, convenience, parking, walking, waiting times, age, preferences etc., and select the option that maximises their utilities [

25,

26]. Towards the two ends of the curve, there are the captives’ zones. At the right-hand side end, there are the captives to option 1 (say PT) with a very large cost difference; those who cannot access private cars because of the very high cost (they do not own cars, don’t possess driving license or physically impaired, and so on). At the left-hand side of the curve, there are the less usual type of travellers, those who are captives to option 2 (say private cars). Those are those travellers who do have access to the private cars but not to public transportation options because they live far from them for example or don’t perceive public transportation as a feasible option of travel for them as the case in Riyadh and many other similar cities. In most of the low-level of income countries’, there are more “captives” to public transportation options than to private cars.

In higher income cities and countries that have specific cultures, the captivity to the private car is experienced. For example, in the city of Riyadh and most cities in the KSA, almost all travellers are captives or confined to the private cars rather than being choosers between the private and public options of travel. This is a result of the relatively high-income levels in the country, very high level of car ownership and the very low level of provision of public transportation or in some cases the complete lack of it. This, in addition to the cultural norms of not accepting to ride on the public modes of travel, makes it a big challenge to expect travellers in these cities to use public transport.

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is working towards achieving more sustainable travel behaviour and attitudes by constructing very high level of service public transportation options including a state-of-the-art metro system, which is very near completion and operation. The local travellers, therefore, are aware of such options and aware of the need to shift some of their travel activities towards such options [

1,

4]. Moreover, a large proportion of the population have travelled abroad and to the neighbouring countries and acquired different travel experience and awareness of the public modes of transportation. All these factors are expected to lead to changing travel behaviour and attitudes towards public transportation systems.

The theory of random utility is based on the assumption that individuals make decisions that maximise their benefits or utilities and that they have full information on all available option in their choice sets. The theory is heavily used in travel behaviour and travel choices. The utilisation of the random utility, or discrete choice models that model decision-makers choices from a set of mutually exclusive options have been adopted in this study. The theory of random utility is based on the assumption that individuals make decisions that maximises their benefits or utilities and that they have full information on all available option in their choice sets. The theory is heavily used in travel behaviour and travel choices. The utilisation of the random utility, or discrete choice models that model decision-makers choices from a set of mutually exclusive options have been adopted in this study.

There are very few available publications on the modal choice and use of travel options in countries such as the KSA and other similar oil rich countries. Relevant studies on these focusses include who claim that high income and economic factors have contributed to shaping the lifestyle in Saudi Arabia that resulted in the high dependency on private cars [

3]. A study reported on a stated preference investigation that assessed the potential commuters’ perception towards the proposed metro system in Riyadh, as a function of some socio-economic as well as some level of service variables [

1,

4]. Other studies include investigation of public perception on public transportation system in Dammam [

28]. There is a lack of studies however, that are looking and investigating the public attitudes, perception and acceptability of public transportation systems in these countries.

Dubai is a neighbouring city to KSA, that was the first Arabic Gulf city to introduce integrated transport planning, implement travel demand management and build a metro system in order to achieve shifting car traffic to public transport traffic. The aim was also to reduce negative traffic impacts and achieve the sustainability goals. Such shift of demand for public service entails not only market motivations to bringdown private vehicle ownership and increase the public transport services, but also an understanding of how much peoples are willing to use and pay for improved public transport services. As well as building public transportation systems, Dubai has introduced financial incentives and disincentives, legislative measures and raising awareness programs in order to facilitate the shift. This approach has resulted in success to shift some of the car trips to public transportation, walking, cycling as well as increasing acceptability of such options [

29,

30].

Oman is another Middle Easter country that has identified the importance of public transportation modes of travel. In a public opinion study that was carried out in Oman, it was reported that public transport facilities in the city are minimal and do not meet the demand, and that the private car is still the main dominant mode of travel in the cities [

31]. Marketing of public transport services is constrained by certain issues including the socio-cultural and physical environments. The study produced recommendations to policy makers in Oman to establishing viable options to public transport solutions. Doha city in Qatar, addressing the rapid-growing demand on transportation in the city and in order to reduce the traffic congestion on the roads, the country has built a new metro system to connect all the major points in the country. The metro network has four lines with an overall length of approximately 340 km and 98 stations [

32].

Understanding issues related to travel behaviour and mode choices have dominated many researchers and scholars’ interest. Many studies have been performed on different aspects of travel patterns, choices and decisions. The factors that are included in the cost functions have been developed further on to include more characteristics such as social factors, modes’ characteristics such as comfort, reliability and attitudinal factors [

20,

21,

22,

23].

Impacts of social economic factors on travel behaviour and their influence on the modal choices are evident in the literature. A number of studies reported some gender differences in terms of accessibility and travel experiences in a case study of Sofia, Bulgaria and Germany [

32,

33,

34]. They report that women have less accessibility in comparison with men who use identical travel options. Another study investigated and reported on significant differences of the social implications for using different types of public transportation, including metro and buses in South Asia [

35]. Three studies looked at impact of gender and income, levels of education, age, employment status and car ownership on travel behaviour and choices with a specific interest on Saudi women [

35,

36,

37]. An investigation of mobility patterns and its impacts on culture and the structure of the household and relation to the transport patterns in terms of gender differences has been reported [

38]. The study concluded on the variables’ impact of cost of travel and time duration on the choices of modes of travel in relation to employment destinations. Commuters’ perceptions on the employment decentralization and impacts on their mode choices in Chine has been reported in [

37].

Swedish women attitudes towards sustainability have been investigated and reported [

39]. The outcome of the study shows that Swedish women are more affirmative towards sustainability and are more likely to reduce their car travel in comparison with men. A study reported on a recent UK research that young women tend to travel more than young men. The authors also concluded that young men travelled substantially less than their counterpart young men in previous generations, which could indicate that different generations face different socio-economic contexts which impact on mobility trends. Similarly, Germany studies have found that gender impacts also affect travel behaviour.

Household structure and patterns of mobility on modal choices in Paris have been investigated and reported [

40]. The impacts of position in the family on work trips behaviour and travel in Oslo have been assessed and stated [

41]. In a comparative assessment, assessed the lower income categories of women and their levels of accessibility to public transportation in China and India.

A study on the demographic variables in Libya such as age and gender has shown a significant contribution to explain mode choice behaviour. In addition, the study showed that men were less likely than women to shift to public transport [

43]. They also found that women tend to travel by car more often as passengers, while men tend to be the drivers. A study found that for students in Beirut, gender is one of the main factors affecting mode choice. Compared to females, males were more likely to use the bus. A study investigated the travel characteristics of female college students in Saudi Arabia. They found that 57% travelled as car (or van) passengers and 39% travelled by bus and over half (53%) were captives to their current mode of transport.

There has also been significant research on gender differences and travel patterns in the West with less research has been done in other part of the world including the Middle East, where cultural and background factors are significantly different than they are in the West, which could have impacts on travel behaviour [

38,

39,

40]. For example, some studies have attempted to examine gendered differences in travel behaviour in the Arab world [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45]. In such countries, women’s travel attitudes and behaviour are affected by economic and geographical factors as well as other social and cultural differences and restrictions.

Logistic regression analysis is a very extensively utilised analysis tool to analyse relationships between a dependent and a number of independent variables, using the concept of random utility. In regression analysis, the dependent variable is often discrete, with one or more possible options, and is considered binary or multiple classes. This type of analysis uses linear regression estimation and results in a logit function that best describe the function form between the dependent and independent variables. In regression analysis when the dependent variable Z is a continuous variable, given by eqn. (1):

where f (x) is linear in the parameters function and ε is the error term that can follow a distribution, and a model will result based on the type of utilised distribution ([

25,

26]. While the multinomial logit models allow for more than two categories of the dependent variable, the binary logit models allow only for two categories. The calibration of a binary or multinomial logistic regression model (with dependent variable classes) involves the calibration of the independent coefficients that predict the probability of the outcome of interest. One possible form of the function is the linear in the parameters form with probabilities are given by the following expression in eqn. [

46,

47]:

ln (prob.(an event occurring))/(1-prob.(an event occurring))

The coefficients in the logistic regression give information as to how much the logit changes depending on the independent variable values. This is applicable for two events, but when there are more than two events this binary logistic regression can be extended. The term on the left-hand side is referred to the log of the odds that an event occurs. The Logit model (binary or multiple) is mostly estimated using maximum likelihood estimation methods. These methods estimate the values of the parameters of an assumed probability distribution, given some observed data [

25]. Regression techniques are also used to evaluate many applications in the area of discrete choice analysis [

25].

Where the dependent variable is ordinal, the logistic regression analysis is referred to as ordinal logistic regression (OLR). When there is a systematic order in the de-pendent variable classes or categories, the ordinal logistic regression can be used to predict the dependent variable as a function of independent variables. To calibrate the coefficients of an ordinal logistic regression model, the levels of the dependent variable have to be defined [

25,

26,

27]. The mathematical formula of the odds of proportional of the OLR can then be written as in eqn. (3):

3. Methodology

3.1. Methodology Framework

As discussed above, the main aim of this research is to investigate attitudes and anticipated behaviour towards public transportation system in the city of Riyadh in the KSA in an era of national reform. The methodology is summarised under the following stages:

Design and implement a questionnaire survey to assess travellers’ attitudes, perception and behaviour towards public transportation options.

Carryout a general analysis of the results using R software. These general results show the main factors that affect choice behaviour and choice of modes of travel.

Identify relevant important factors that affect choice behaviour

Exploit these identified factors in an ordered logit model to assess the impact of the socio-economic factors on the stated attitudes and intended behaviour towards public transportation usage

Assess the model performance and discuss the results.

3.2. Experiment Design

An online questionnaire survey has been designed and piloted on a sample of 19 participants from the Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University (PNU) to test the clarity of the questions, the length of the questionnaire and the practicality and worth of each of the questions. The questionnaire was then finalised, administered and sent online to participants including both males and females using social media and Saudi’s universities through the research team and other colleagues at the PNU University in Riyadh. The questionnaire link was accessed by over 2000 potential participants. Finally, 399 completed questionnaires were received. The survey was implemented between August and November 2022. The final version of the questionnaire included questions to collect data on:

1. Modes of travel (frequently used modes, less frequently used modes, non-used modes, departure times, …)

2. Travel characteristics (travel time, travel costs, waiting time, walking time, number of times to fuel your car weekly, cost of fuelling, ..)

3. Personal socio-economic characteristics (age, gender, position in the family, income)

4. Household socio-economic characteristics (HH structure, number of driving licenses in the HH, number of private drivers, )

5. Education and employment

6. Attitudinal questions towards level of awareness of the new transportation systems in Riyadh

7. Attitudinal questions towards the importance of factors relate to the transportation system (safety, reliability, delays, congestion, …)

8. Attitudinal questions towards possible travel demand management measures (TDM) to include (pricing, parking, public transportation, access control, …)

9. Reported intent to use public transportation modes when they become available questions. The respondents were asked to report on their future intent to use public transportation modes, as they become available, and to report these intentions on a three-point Likert scale: {will definitely shift to PT, I might do and definitely will not shift to PT.

10. General questions on the experience with the questionnaire (time, clarity of questions, any further comments, etc.)

In this paper, information gathered from questions 1-6 & 9 above have been analysed and will be discussed. An initial assessment of the data that was collected was carried out in order to assess and finalise the selected factors/ variables in the final analysis as follows:

1. The socio-economic characteristics that are selected as independent variables are suggested from previous literature to be relevant to mode choice analysis considering the specific context.

2. A correlation analysis between each independent variable and the dependent variable was carried out in order to select the factors that are relevant for this research.

3. A correlation analysis between the independent variables to eliminate any highly correlated variables.

The list of the selected variables and their general statistics are presented in

Table 1 below.

3.3. Ordered Logistic Regression Model

The future intent to use public transportation modes responses were used to represent three ordered response values. In addition, from the responses which showed relevance to the stated attitudes towards public transportation systems, seven socio-economic independent variables were selected to assess the likelihood of Saudi population shifting to public transportation options. The stated responses to the questions regarding the likelihood of using public transportation was expressed on a three-point Likert scale. Therefore, the ordered logistic regression techniques are applied.

In this setting, the outcome (or dependent) variable of the model is the intention to use public transportation expressed on a three-point Likert scale {will definitely shift to PT, I might do, will definitely not shift to PT}, when the metro system and other public transportation modes are introduced in the city. The independent variables are socio-economic and attitudinal factors that proved relevant from the general statistics part of the analysis.

Assume V to be the total number of levels of the dependent variable (in this case V=3) and I to be the number of independent variables (I=6). The mathematical formula of the odds of proportional model can then be written as in eqn. (4):

Where, v is the level of an ordered category of the dependent variable = 1, 2, 3 and I corresponds to independent variables = 1,…6 as seen in

Table 2 below. In this case, v= 1 refers to ‘will definitely shift to PT’, v = 2 refers to ‘I might do’, v = 3 refers to ‘will definitely not shift to PT’. In addition, when i = 1 refers to ‘gender’ i = 2 refers to ‘position in the HH’, i = 3 refers to ‘possession of driving license’, i=4 refers to ‘education’, i = 5 refers to ‘number of people in the HH’ and i=6 refers to ‘individual monthly in-come’. An ordinal logistic regression or an ordered logit model was developed based on responses received from the survey.

The definitions of the ordinal logistic regression are that all the coefficients of the dependent variable across all categories have equal slope. This is tested using the parallel line test or the Brant test. In this investigation, a comparison of the ordinal model with one set of coefficient estimates for all categories of each of the independent variables (i.e. Null Hypothesis of the ordered model) is compared with a model that have a separate set of coefficients for each category (referred to here as the “General model”), and the assumptions of the ordered model have been accepted. The objective behind using OLR is to predict the dependent variable (V) as a function of the five independent parameters that are presented in Table 3.

4. Analysis of Survey Data

4.1. General Statistics of the Analysis

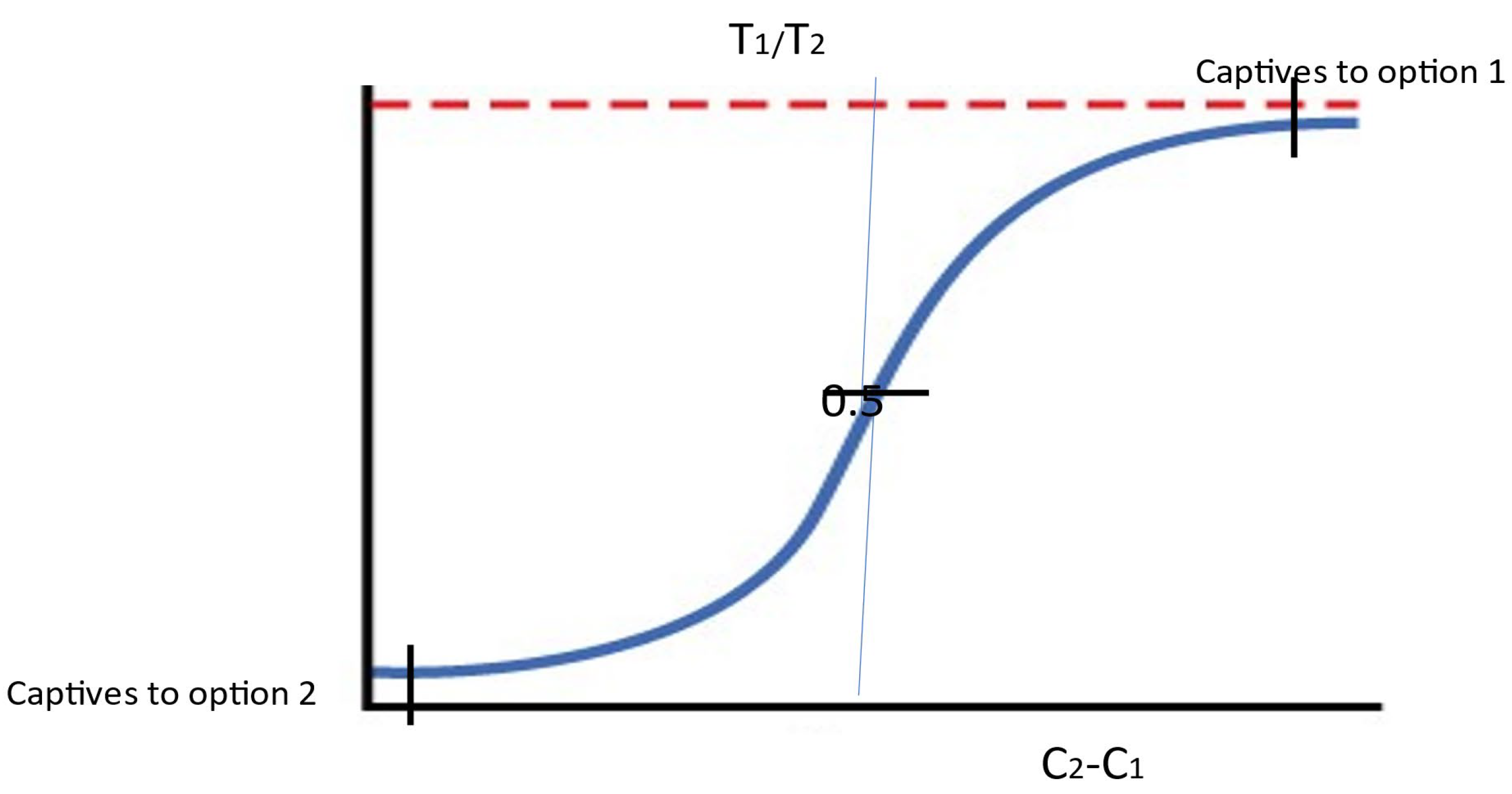

The analysis of the outcome of the survey that was carried out with 399 participants is presented in this section. The number of those surveyed categorised by each socio-economic group and overall percentages withing each category as presented in

Table 1 and

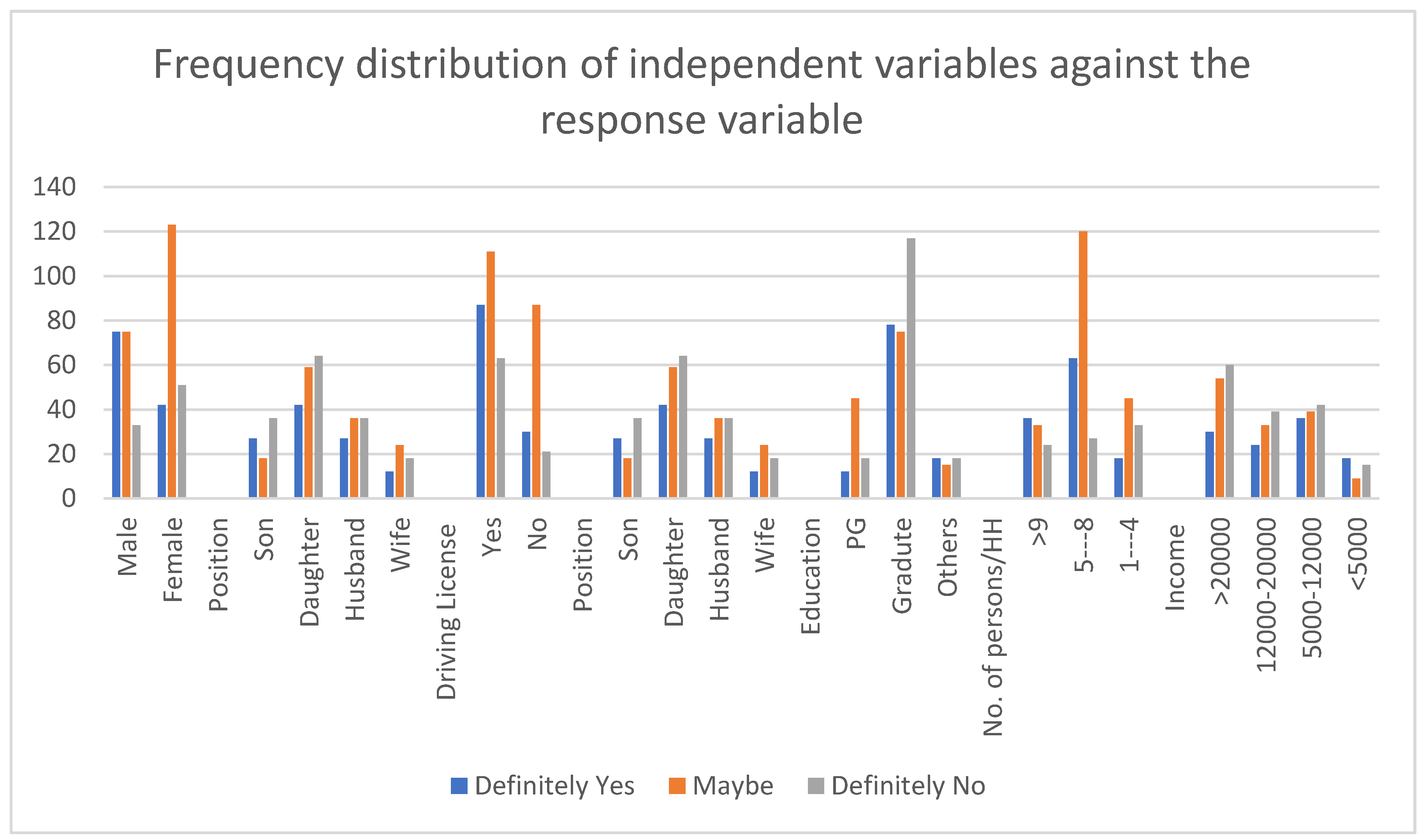

Figure 2 (a-f).

The general characteristics of the participants show that 54.14% of participants were female and 45.86% were male. The age question was not included in the survey since this kind of questions might be considered a sensitive piece of information which might cause the participants to be uncomfortable. It was also thought that there are other questions in the survey that would be a sufficient indicator of the participant’s age. The participants were also asked to report on their position of them in the family. The results indicated that the “daughter” is the majority reported position in the sample (40.60%), this is followed by the husband (24.81%), the son ((21.05%) then lastly the wife (13.53%).

Other socio-economic characteristics include possession of driving license. About 67% of the participants reported that they possess a driving license while 33% do not. Majority of those who don’t possess a driving license are the daughters and wives. Over 70% of those who do not possess a driving license in Riyadh are daughters and over 20% are wives. Sons and husbands are minorities in this category. It should be noted here that Saudi women just started driving five years ago and the numbers of female drivers have been increasing constantly. In terms of education, three levels are defined; PG holders represent 18.05% of the sample, the university graduates represent 67.67% while other education levels combined represent 14.29% of the sample.

The total number and percentages of participants falling in four categories of number of persons in the household, show that the category of 5-7 persons per household is the largest category in the sample in terms of number of participants (52.63%). The two categories (1-4 persons/HH and 7-9 persons/HH) are equal and each category represents about 22.5% with the category >9 persons/HH is the lowest category with a percentage of 1.5% only. It is well documented in the literature that in Saudi Arabia, there are the extended families and that the family size is generally of a larger number of persons than the case in the West.

The general statistics also show the distribution of the participants to the four in-come groups. Just over 36% of the sample fall in the income category monthly of >20,000 SR (>$5300). The second largest category is just over 29% of participants fall in the cat-egory of monthly income of 5000-12000 SR ($1330-3200), about 24% fall in the category 12,000-20,000 SR ($3200-5300) and the final category represents only 9% of participants of monthly income <SR 5000.

4.2. Travel Characteristics of Participants

Participants were also asked to report on their travel experience and on their most frequently used modes of travel over the previous month. The information on mode of travel were coded to include “always” and “almost always” categories. This is because most participants in the survey and in the Kingdom mostly use the private cars (>70%).

Table 2 provides a summary of the mode choice statistics of the participants against some socio-economic characteristics. From the Table, it appears that the private car is the most dominant mode of transportation in Riyadh. It also appears that the public transportation is the most unused mode of travel in the city (<0.8%). When participants asked about how often they use public modes of transportation, which is currently the bus, only three working females reported that they use it always. The three females are of the lowest income group, do not own a private car and they all in the category of household size of 5-7 persons in the household. In another question in the survey, the participants were asked to report on their level of awareness of the new public transportation systems that are currently constructed in Riyadh. About 25% of the participants said that they are not aware of the newly introduced public transportation options while 75% said they are aware of the new options of travel including the metro. This is an important piece of information, as the level of awareness could well have an impact on the level of acceptability.

Sustainability is a big call however, in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia at the current time and the measure makers are very keen to implement measures to encourage more walking activities. While walking is a very important mode of travel in particular for the short journeys, as well as one of the sustainable modes of travel, in most world cities, in Riyadh walking is not a popular option. Walking trips to work, only about 8% reported that they always go to work walking; these were all journeys of less than 30 minutes. This of course makes sense since Saudi Arabia is a hot country in the whole and not many people would be observed to be making their daily trips to work on foot. About 60% of participants reported that they never walk to work, and the rest reported that sometimes they walk to work. The reported journey times for over 70% of this latest category is also less than 30 minutes, while for the other 30% of them the journey time is between 30-60 minutes.

5. Ordered Logit Regression Model

As discussed, instead of investigating the currently used modes of travel as the selected option, the participants were asked to report their intention to use public transportation option when these become available such as the Riyadh metro which is planned to open in the very near future. It is believed therefore, that the expressed responses will be realistic since the participants are aware of the option presented to them rather than asking about some hypothetical options.

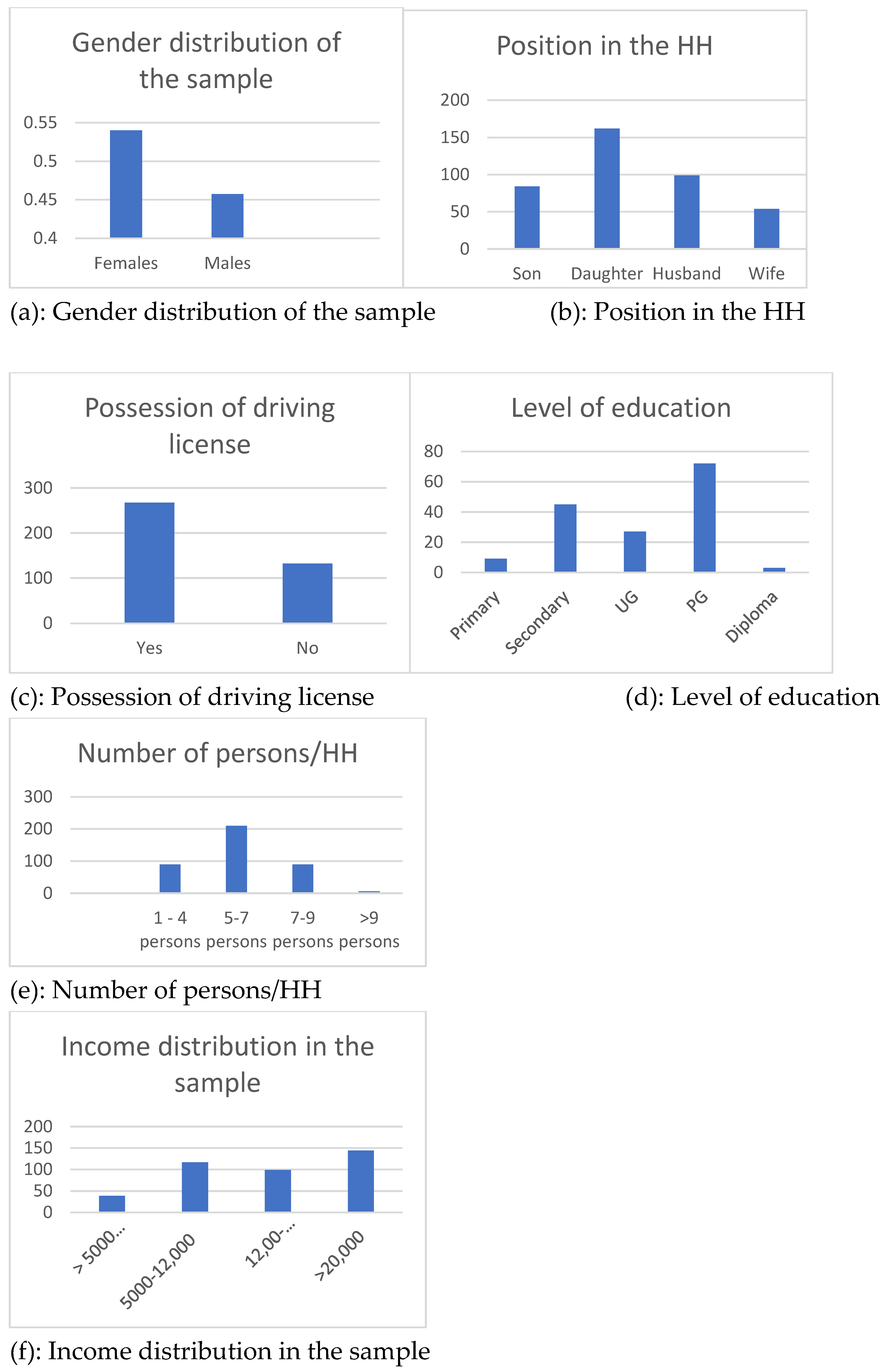

From the results it appears that about 40% of the sample reported that they would definitely shift to PT, 40% said they might shift and just under 20% reported that they definitely would not shift to PT options. These responses were used to represent an ordered response values and were modelled alongside the selected seven independent social economic variables to assess the likelihood of Saudi population shifting to public transportation options using the ordered logistic regression. The model’s parameters estimations are presented in

Table 2. The analysis was carriedout using R software [

48]. The odds of proportional model can then be written as:

logit [P(Y≤ v)] = αv – ΣβiXi (4)

An ordinal logistic regression or an ordered logit model was developed based on responses received from the survey. The coefficients’ estimates of the independent variables, the odd rations and goodness of fit statistics of the OLR model are presented in

Table 5 and

Figure 3 below.

Figure 4 shows the frequency distribution of independent variables against the response variable. From the graph it appears that there is an overall positive intention towards using the public transportation systems in Riyadh when they start operation from the participants population. It appears that males as keen as women on using public transportation. Previous literature suggest that women are extra supportive of public transportation modes than men [

37,

38]. Participants who possess a driving li-cense seem to have higher intent to use public transportation than those who don’t. In terms of position in the family, daughter showed highest interest in using public transportations over the other members of the family. University graduates showed most interest in public transportation modes than participants with other qualifications. Assessing the impact of income on the intent of using public transportation showing that participants with highest income groups indicated highest percentage of rejecting the use of PT, which might be expected and also supported by previous literature.

The results are dedicated on the intent to use public transportation services, once they become available, in order to achieve sustainability and improve overall travel efficiencies.

Table 5 shows the coefficient estimates of the OLR model, the odd ratios and the t-statistical significance values. coefficient’s estimates and their exponential values. From the Table, it is evident that the proportional odds model shows the positive effects of all coefficients, which are statistically significant (p <0.05) according to Wald test. From the results, for a one unit increase in the “male” group, we expect a 0.775 increase in the log odds of being at the higher likelihood to use future public transportation, given all other variables in the model are held constant. Furthermore, for a one unit increase in the “male” gender group, the odds of being at the highest level of using public transportation versus the combined two other levels, is 2.171 greater, given that all of the other variables in the model are held constant. For a one unit increase in the “Son” position cate-gory, we expect a 0.501 increase in the log odds of being at the higher level of using future public transportation given all of the other variables in the model are held constant. Furthermore, for a one unit increase in the “Son” position category, the odds of being at the highest level of using public transportation versus the combined two other levels, is 1.6665 greater, given that all of the other variables in the model are held constant. On the other hand, for a one unit increase in the “daughter” position category, we expect a 1.274 increase in the log odds of being at the higher level of using future public transportation given all of the other variables in the model are held constant. Furthermore, for a one unit increase in the “daughter” position category, the odds of being at the highest level of using public transportation versus the combined two other levels, is 3.575 greater, given that all of the other variables in the model are held constant.

For a one unit increase in the “Yes” category of driving license variable, we expect a 2.809 increase in the log odds of being at the higher likelihood to use future public transportation, given all of the other variables in the model are held constant. Furthermore, for a one unit increase in the “Yes” category of driving license category, the odds of being at the highest level of using public transportation versus the combined two other levels, is 16.593 greater, given that all of the other variables in the model are held constant. For a one unit increase in the “University Graduates” category of level of education variable, we expect a 3.213 increase in the log odds of being at the higher likelihood to use future public transportation, given all of the other variables in the model are held constant. Furthermore, for a one unit increase in the “university graduates” category of level of education category, the odds of being at the highest level of using public transportation versus the combined two other levels, is 24.853 greater, given that all of the other variables in the model are held constant.

For a one unit increase in the “Income >20K” category of Income variable, we expect a -1.443 reduction in the log odds of being at the higher likelihood to use future public transportation, given all of the other variables in the model are held constant. Moreover, for a one unit increase in the “university graduates” category of level of education category, the odds of being at the highest level of using public transportation versus the combined two other levels, is 0.236 greater, given that all of the other variables in the model are held constant. The cut points shown at the bottom of the coefficient estimates, indicate where the latent variable is cut to make the three levels that we observe in the data. Table 4 also provides evidence for the model’s goodness of fit and its ability to predict the outcome variable. The loglikelihood values of the model with zero coefficients are compared with those of the final model with all independent variables, which demonstrates the improvement in the goodness of fit of the model. The p-values show the level of significance of the models. The results of the test of parallel lines show evidence for the appropriateness of the ordinal logit model and its estimates (Null Hypothesis of the ordered model) that is superior to a model with a separate set of coefficients for each category, which is the general model.

A factor that could affect social change is the level of awareness of the new PT systems in Riyadh. For a one unit increase in the “Yes” category of level of awareness variable, we expect a 2.611 increase in the log odds of being at the higher likelihood to use future public transportation, given all of the other variables in the model are held constant. Furthermore, for a one unit increase in the “Yes” category of level of aware-ness category, the odds of being at the highest level of using public transportation versus the combined two other levels, is 13.626 greater, given that all of the other variables in the model are held constant.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

The paper investigates the perceptions, attitudes and anticipated behaviour in Riyadh city towards public transportation systems taking into account the current situation, the current vision of the country and the expressed preferences and attitudes of the individuals. This is a very significant contribution; if social change is emerging and modal shift to public transportation is increasing, that would be very important momentous towards achieving sustainability in the Kingdom. Currently, over 98% of the trips in the city of Riyadh are carried out by the private car while the government is progressing towards sustainable travel behaviour. The country is constructing a massive metro system which is being near completion and operation. The new metro system is being known and witnessed by all residents of the city, during the construction phases, and so it is hoped that it will encourage positive attitudes and behaviour of the citizens to become more sustainable. It is very timely and critical therefore, to investigate and assess the potential intent to use this system.

The study involves an on-line questionnaire survey that has been designed, piloted, finalised, administered and sent online to participants including both males and females using social media. The questionnaire link was accessed by over 2000 potential participants and 399 were finally completed. The survey was implemented between August and November 2022. The final version of the questionnaire included information on modes of travel, travel characteristics, personal and household Socio-economic characteristics, education and employment, attitudinal questions towards the transportation system in Riyadh, attitudinal questions towards the importance of factors relate to the transportation system, attitudinal questions towards possible travel demand management and reported intent to use public transportation modes when they become available. In this paper, individual and HH socio economic data, education, income and attitudinal questions towards the transportation system in Riyadh were exploited and analysed.

A mode choice model for the future choices of public transportation was calibrated including seven independent variables: gender, possession of driving license, position in the family, level of education, number of persons in the family and income. This is in addition to a variable that would affect social change; the level of awareness of the newly introduced PT systems in Riyadh has been included.

The ordered logistic regression analysis (OLR) was utilised in this research. The response variable was expressed as three points on the Likert scale representing intentions of participants to use public transportation option, as they become available. The model results show statistical significance of all the variables that were used with an overall significant goodness of fit of the model. The model’s results show that overall, it appears that about 40% would be definitely shifting to PT should a decent public transportation option become available, 40% said they might shift and just under 20% reported that they definitely would not shift to PT options. This shows a much-improved modal split towards public transportation than what is the current case which shows that the current use of the public transportation is only about 2%.

The results also show that the “daughters” in the family were the highest devotes and keen to use public transportation options than the sons and the husbands. This finding is compatible with previous research which showed that females in general are keener and more supportive to use public transportation options. This is an interesting finding as well from the point of view that the current era in the KSA is characterized by empowering women; This is to be added to many other examples and evidence that reflect and witness women’s achievements [

13]. Participants with highest income groups were less keen to use public transportation and they were reporting more “definitely not going to use PT”, than other income groups. This is an expected finding, since often higher income individuals sustain higher values of times and are less keen to use public transportation options [

25].

For a one unit increase in the “Yes” category of level of awareness variable, we expect a 2.611 increase in the log odds of being at the higher likelihood to use future public transportation, given all of the other variables in the model are held constant. Furthermore, for a one unit increase in the “Yes” category of level of awareness category, the odds of being at the highest level of using public transportation versus the combined two other levels, is 13.626 greater, given that all of the other variables in the model are held constant. It is very important therefore to try to increase awareness about travelling by public transportation options rather than private car. This is in particularly relevant in cultures of high car dependency and high-income countries.

The paper adds value to the literature by offering a first investigation of willingness to use public transportation in the city of Riyadh, at a very critical time where there is abundant knowledge and experience of both the new public transportation options that are being constructed and very soon will be operated in the city, and the very high level of congestion that everyone in the city have experience with. The paper suggests that the choice of mode of choice, as a rational choice, is determined by the travellers’ social and economic characteristics as well as the influences from the national vision.

The social studies are very expedient for the understanding of the attitudes and behaviour, and hence to allow the design and planning for appropriate travel services and programs that would support the national vision [

28,

29,

30]. With the local transportation authority in Riyadh is about to start operating the new metro system, the findings from this research could offer help for better understanding of the Riyadh’s population attitudes and preferences. Carrying out this type of research is a possible means of raising awareness and inform the travellers of the available transport options and resources to gain public support that is very critical for the success of public transportation projects.

7. Limitations

This is an original and pioneering research in the area of travel behaviour, and attitudes. There are however various limitations of the research as discussed in this section. The survey was distributed and administered using online means with more than 2000 access to the link. Only 399 completed surveys, however, were received. While this number is acceptable for the analysis, larger feedback would no doubt provide more accurate results. The online survey might have affected the types of respondents; not all population are able to get access to online surveys. This is in particularly true for the older population. Ordered logit models have been used to analyse the willingness to public transportation. Other types of models could have been employed including logistic regression and linear and continuous models. The results presented in this research is limited to one city which is Riyadh. This research should be extended to other cities in the Kingdom. Further research needs to be carried out involving local authorities and transport planners, so actual measures and programs can be built in the design of the surveying methodology. The current research includes seven independent variables, that were showing positive correlation with the response variable. Other variables could also be included in future research including age, level of employment, altitudinal opinions, stated preferences surveys and other methodological approaches.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, through the Research Funding Program, Grant No. (FRP-1443-17).

References

- Omar Alotaibi & Dimitris Potoglou (2017) Perspectives of travel strategies in light of the new metro and bus networks in Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia, Transportation Planning and Technology, 40:1, 4-27. [CrossRef]

- Alqahtany, A. 2014. The Development of a Consensus-Based Framework for a Sustainable Urban Planning of the City of Riyadh. Cardiff: Cardiff School of Engineering, Cardiff University.

- Mubarak, F. A.2004.“Urban Growth Boundary Policy and Residential Suburbanization: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.”Habitat International28 (4): 567–591.

- Youssef, Zaher, Habib Alshuwaikhat, and Imran Reza. 2021. "Modeling the Modal Shift towards a More Sustainable Transport by Stated Preference in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia" Sustainability 13, no. 1: 337. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, C. R., A generalized multiple duration proportional hazard model with an application to activity behaviour during the evening work-to-.

- home commute, Transportation Research Part B 30, 1996, 465-480.

- Tim Schwanen, Patricia L. Mokhtarian, What affects commute mode choice: neighborhood physical structure or preferences toward. n: Mokhtarian, What affects commute mode choice. [CrossRef]

- neighborhoods?, Journal of Transport Geography, 13, 2005, 83–99.

- Sofia Martin-Puerta, Commuting mode choice: Motivational determinants and road users profile, Transport Research Arena, 2014, Paris.

- Boudon R (1982) The Unintended Consequences of Social Action. London: Macmillan Press. Coleman JS (1990) Foundations of Social Theory. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Aguiar F, de Francisco A (2009) Rational choice, social identity, and beliefs about oneself. Philosophy of the Social Sciences 39(4): 547–71.

- Coleman JS (1990) Foundations of Social Theory. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Coleman JS (1986) Social theory, social research, and a theory of action. Am J Sociol 91:1309–1335.

- Liebe, U., Preisendörfer, P. (2010). Rational Choice Theory and the Environment: Variants, Applications, and New Trends. In: Gross, M., Heinrichs, H. (eds) Environmental Sociology. Springer, Dordrecht. [CrossRef]

- Saleh, W.; Malibari, A. (2021) Saudi Women and Vision 2030: Bridging the Gap? Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 132. [CrossRef]

- ang, X., Day, J. E., Langford, B. C., Cherry, C. R., Jones, L. R., Han, S. S., & Sun, J. (2017). Commute responses to employment decentralization: Anticipated versus actual mode choice behaviors of new town employees in Kunming, China. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 52, 454-470. [CrossRef]

- A Vega, Amaya, Reynolds-Feighan, Aisling (2008)Employment Sub-centres and Travel-to-Work Mode Choice in the Dublin Region. Journal of Urban Studies. 1747-1768, Volume 45, Number 9.

- Yang, X., Day, J. E., Langford, B. C., Cherry, C. R., Jones, L. R., Han, S. S., & Sun, J. (2017). Commute responses to employment decentralization: Anticipated versus actual mode choice behaviors of new town employees in Kunming, China. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 52, 454-470. [CrossRef]

- Polk, M. Are Women Potentially More Accommodating Than Men to a Sustainable Transportation System in Sweden? Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 2005, 8, 75–95.

- Bernard, A.; Seguin, A.; Bussiere, Y. Household Structure and Mobility ‘Patterns of Women in O-D Surveys: Methods and Results Based on the Case Studies of Montreal and Paris; The National Academies of Sciences: Washington, DC, USA, 2013.

- Hjorthol, R.J. Same city--different options: An analysis of the work trips of married couples in the metropolitan area of Oslo. J. Transp. Geogr. 2000, 8, 213–220. [CrossRef]

- Frank, L., Bradley, M., Kavage, S. et al. (2008) Urban form, travel time, and cost relationships with tour complexity and mode choice. Transportation 35, 37–54. [CrossRef]

- Roya Etminani-Ghasrodashti, Mahyar Ardeshiri, (2015) Modeling travel behavior by the structural relationships between lifestyle, built environment and non-working trips, Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, Volume 78, Pages 506-518, ISSN 0965-8564. [CrossRef]

- Narisra Limtanakool, Martin Dijst, Tim Schwanen (2006) The influence of socioeconomic characteristics, land use and travel time considerations on mode choice for medium- and longer-distance trips, Journal of Transport Geography, Volume 14, Issue 5, Pages 327-341, ISSN 0966-6923. [CrossRef]

- Salter, R.J. (1976). Modal split. In: Highway Traffic Analysis and Design. Palgrave, London. [CrossRef]

- Lathrop, G. T., Hamburg, J.R., and Young, G. F. Opportunity-Accessibility Model for Allocating Regional Growth. Highway Research Record 102, 1965, pp. 54-66.

- De Dios Ortúzar, J. & Willumsen, L. G. (2011) Modelling transport, John wiley & sons.

- W.H. Greene, D.A. Hensher (2003) A latent class model for discrete choice analysis: contrasts with mixed logit. Transportation Research Part B: Methodologica.

- Al-Rashid, M.A.; Nahiduzzaman, K.M.; Ahmed, S.; Campisi, T.; Akgün, N. (2020) Gender-Responsive Public Transportation in the Dammam Metropolitan Region, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability, 12, 9068.

- Al-Fouzan, S.A. (2012) Using car parking requirements to promote sustainable transport development in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Cities, 29, 201–211. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, G.A., 2012. Evolution of the transportation system in Dubai. Network Industries Quarterly, 14(1), pp.7-11.

- Abouelhamd, I., Radwan, I. and Abed, O., 2020. Conceptual Development Solutions for Traffic Jams & Accidents in Dubai City.

- Rakesh Belwal, Shweta Belwal, (2010) Public Transportation Services in Oman: A Study of Public Perceptions, Journal of Public Transportation, Volume 13, Issue 4, Pages 1-21, ISSN 1077-291X. [CrossRef]

- Kwan, M.-P.; Kotsev, A. Gender differences in commute time and accessibility in Sofia, Bulgaria: A study using 3D geovisualisation. Geogr. J. 2014, 181, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Best, H.; Lanzendorf, M. Division of labour and gender differences in metropolitan car use: An empirical study in Cologne, Germany. J. Transp. Geogr. 2004, 13, 109–121. 2004; 13, 109–121. [CrossRef]

- Boarnet, M.G.; Sarmiento, S. Can Land-use Policy Really Affect Travel Behaviour? A Study of the Link between Non-work Travel and Land-use Characteristics. Urban Stud. 1998, 35, 1155–1169. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.P., Sustainable commute in a car-dominant city: factors affecting alternative mode choices among university students, Transportation Research Part A – Policy and Practice 46. 2012, 1013–1029. [CrossRef]

- Saleh, W.; Malibari, A. (2021) Saudi Women and Vision 2030: Bridging the Gap? Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 132. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X., Day, J. E., Langford, B. C., Cherry, C. R., Jones, L. R., Han, S. S., & Sun, J. (2017). Commute responses to employment decentralization: Anticipated versus actual mode choice behaviors of new town employees in Kunming, China. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 52, 454-470. [CrossRef]

- A Vega, Amaya, Reynolds-Feighan, Aisling (2008)Employment Sub-centres and Travel-to-Work Mode Choice in the Dublin Region. Journal of Urban Studies. 1747-1768, Volume 45, Number 9.

- Polk, M. Are Women Potentially More Accommodating Than Men to a Sustainable Transportation System in Sweden? Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 2005, 8, 75–95.

- Bernard, A.; Seguin, A.; Bussiere, Y. Household Structure and Mobility ‘Patterns of Women in O-D Surveys: Methods and Results Based on the Case Studies of Montreal and Paris; The National Academies of Sciences: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. The National Academies of Sciences: Washington, DC, USA.

- Hjorthol, R.J. Same city--different options: An analysis of the work trips of married couples in the metropolitan area of Oslo. J. Transp. Geogr. 2000, 8, 213–220. [CrossRef]

- Sirnivasan, S. A Spatial Exploration of the Accessibility of Low-Income Women; Chengdu, China and Chennai, India. In Gendered Mobilities; Uteng, T.P., Cresswell, T., Eds.; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 2008; pp. 173–192.

- Abuhamoud, M.; Rahmat, R.; Ismail, A. Transportation and its concerns in Africa: A review. Soc. Sci. 2013, 6, 21–63. [CrossRef]

- Al-Ahmadi, H.M. Travel Characteristics of Female Students to Colleges in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J. Eng. Res. 2006, 3, 79–83. [CrossRef]

- Hamed, M.; Olaywah, H. Travel-related decisions by bus, service taxi, and private car commuters in the city of Amman, Jordan. Cities 2000, 17, 63–71. [CrossRef]

- Mangham, L.J., Hanson, K. and McPake, B., (2009). How to do (or not to do?). Designing a discrete choice experiment for application in a low-income country. Health policy and planning, 24(2), pp.151-158. [CrossRef]

- Ledolter, J., (2013). Multinomial logistic regression. Data Mining and Business Analytics with R, pp.132-149.

- Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, Bolstad B, Dettling M, Dudoit S, Ellis B, Gautier L, Ge Y, Gentry J, Hornik K, Hothorn T, Huber W, Iacus S, Irizarry R, Leisch F, Li C, Maechler M, Rossini AJ, Sawitzki G, Smith C, Smyth G, Tierney L, Yang JY, Zhang J. Genome Biol 2004: 5(10); R80.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).