1. Introduction

Cardiac myosin powers heart contraction through the ATP-dependent cyclic interactions between myosin cross-bridges and actin-tropomyosin (Tm)-troponin (Tn) thin filaments [

1]. In addition to the known Ca

2+-Tm-Tn regulatory system [

2], myosin together with the regulatory (RLC) and essential (ELC) light chains play important roles in the regulation of muscle contractility and heart performance [

3,

4]. Many genetic mutations in cardiac sarcomeric proteins, including myosin RLC and ELC, were found responsible for the modulation of myosin motor function and affecting heart performance [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. As myosin light chains are important regulators of the actin-myosin interaction, they constitute a potential drug target for rescue strategies to ameliorate or reverse myosin motor dysfunction and abnormal disease phenotypes [

10,

11,

12,

13].

One such strategy is associated with myosin light chain kinase (MLCK)-dependent phosphorylation of cardiac RLC that has been shown in many studies to be critical for normal heart function [

14,

15,

16]. Myosin regulatory light chain phosphorylation is a critical determinant of myosin motor function and heart performance in healthy and cardiomyopathic hearts; still, little is known about the underlying mechanisms. Cardiac MLCK, the enzyme that phosphorylates RLC, was shown to play a role in cardiogenesis [

17] and myofibrillogenesis [

18]. Upregulation of MLCK is considered a mechanism to promote sarcomere reassembly and enhanced contractility of the failing heart [

17]. Constitutive RLC phosphorylation at ~40% was shown to stabilize myosin motor function in continuously beating hearts [

19]. In the human heart, myosin RLC phosphorylation occurs at serine 15 (Ser-15) and this site was recently shown to be superior to other potential phosphorylation sites of RLC [

20]. We also showed that phosphomimetic RLC variant, in which Ser-15 was replaced by aspartic acid (S15D) mitigated detrimental hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) phenotypes

in vivo [

21] and

in vitro [

20] when placed in the background of HCM-associated RLC mutations.

In the current study, we aimed to test whether the adverse effects of restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM)-E143K ELC and dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM)-D94A RLC mutations that exert severe myofilament impairments could be rescued by phosphomimetic S15D-RLC reconstituted in Tg-E143K versus Tg-WT ELC fibers and in Tg-D94A versus Tg-WT RLC preparations. Left ventricular papillary muscle (LVPM) fibers from Tg mice were depleted of endogenous RLC and subsequently reconstituted with recombinant human cardiac S15D-RLC protein. The data showed beneficial effects of the phosphomimetic RLC on myosin contractile and energetic states in RCM and DCM myocardium that were comparable to the effects achieved with Omecamtiv Mecarbil (OM), an agent used to treat heart failure and systolic dysfunction [

22,

23].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Transgenic mice

All transgenic (Tg) mouse models used in the current study have been characterized in previous papers and used widely in our laboratory [

24,

25,

26]. The following mice were used: Tg-WT RLC (L2, expressing 100% of human ventricular RLC, Swiss-Prot: P10916), Tg-D94A RLC (L1 and L2 expressing 53% and 50% human ventricular mutant D94A RLC), and Tg-WT ELC (L1 and L4, expressing 76% and 71% of human ventricular ELC, Swiss-Prot: P08590) and one Tg-E143K ELC (L2 expressing 55% human ventricular mutant E143K ELC). Male (M) and female (F) mice were used in experiments.

2.2. Recombinant RLC proteins – cloning, expression and purification

To generate recombinant RLC proteins for reconstitution in cardiac muscle fibers, the cDNAs of human cardiac WT-RLC, phosphomimetic RLC variant (S15D-RLC) and DCM-D94A RLC mutant were cloned by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction using primers based on the published cDNA RLC sequences (WT RLC - GenBank Accession No. AF020768, S15D RLC - GenBank accession number ON950401), using standard methods as described previously [

8,

27,

28]. Obtained cDNAs were used for transformation into BL21 expression host cells to express proteins in 16 L cultures that were subsequently purified by ion-exchange chromatography using an S-Sepharose column (equilibrated with 2 M urea, 20 mM sodium citrate, 0.1 mM PMSF, 1 mM DTT, 0.02% NaN

3, pH 6.0) followed by a Q-Sepharose column (equilibrated with 2 M urea, 25 mM Tris–HCl, 0.1 mM PMSF, 1 mM DTT, 0.02% NaN

3, pH 7.5). The RLC proteins were eluted with a salt gradient of 0–450 mM NaCl, and their final purity was evaluated using 15% SDS–PAGE [

8,

27,

28].

2.3. Mechanical and ATP turnover measurements in skinned left ventricular papillary muscle (LVPM) fibers from transgenic Tg-RLC and Tg-ELC mice

2.3.1. Preparation of skinned LVPM fibers

LVPM fibers were isolated from the hearts of 3 to 11 mo-old Tg mice (Tg-WT RLC, Tg-D94A RLC, Tg-WT ELC, and Tg-E143K ELC). Muscle bundles were separated and dissected into small muscle strips (2-3 mm in length and 0.5-1 mm in diameter) in ice-cold pCa 8 solution {10

-8 M [Ca

2+], 1 mM free [Mg

2+] [total MgPr (propionate) =3.88 mM], 7 mM EGTA, 2.5 mM [Mg-ATP

2-], 20 mM MOPS pH 7.0, 15 mM creatine phosphate, and 15 U/ml of phosphocreatine kinase, ionic strength = 150 mM adjusted with KPr} that contained 30 mM BDM and 15% glycerol. After dissection, the bundles were transferred to pCa 8 solution mixed with 50% glycerol (storage solution) and incubated for 1 h on ice. Then the strips were chemically skinned with 1% Triton X-100 and 50/50 (%) pCa 8 and glycerol overnight at 4°C. The fibers were transferred to a fresh storage solution and kept at -20°C for 5–10 days [

24].

2.3.2. Depletion of endogenous RLC from LVPM and reconstitution with recombinant RLC proteins

Tg mouse LVPM preparations underwent extraction of endogenous RLC and reconstitution with recombinant RLC proteins as described previously [

20]. Briefly, depletion of endogenous RLC was achieved by treating small muscle strips ~ 100 µm wide and ~ 1.5 mm long (isolated from glycerinated papillary muscle bundles) with the following buffer: 5 mM CDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 50 mM KCl, 40 mM Tris, 0.6 mM NaN

3, 0.2 mM PMSF at pH 8.4, supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail for 40 min at room temperature. Since depletion of the endogenous RLC may result in partial extraction of the endogenous TnC, cardiac TnC (15 µM) was added to the CDTA-treated strips and incubated in pCa 8 solution for 15 minutes. This reaction was followed by reconstitution of the RLC-depleted muscle strips with the following recombinant proteins: WT-RLC or S15D-RLC for Tg-WT ELC and Tg-E143K ELC, and WT-RLC, S15D-RLC or D94A-RLC for Tg-D94A RLC muscle strips in a pCa 8 solution containing 40 µM RLC of interest for 45 minutes at room temperature. Extraction and reconstitution reactions were carried out with the muscle strips either attached to the arms of a force transducer or free-floating in a 96-well plate. RLC and TnC reconstituted LVPM fibers were then washed in pCa 8 buffer and subjected to force-pCa and super-relaxed (SRX) state measurements or transferred to fresh storage solution and kept at -20°C for 1 – 5 days until used for SRX experiments. The extent of RLC extraction and reconstitution was determined by running experimental LVPM fibers on 15% SDS–PAGE. After staining protein bands with Coomassie Brilliant Blue, the gels were imaged using the Odyssey infrared imaging system (LICOR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA). Determination of the level of RLC depletion and reconstitution was achieved by densitometry analysis (ImageJ software;

https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/). The RLC/ELC band intensities were measured in Tg native, RLC-depleted, and RLC-reconstituted LVPM preparations. The myosin ELC was used as a loading control as it is not affected during the RLC-depletion/reconstitution procedures [

29].

2.3.3. Steady-state force measurements and Ca2+ dependence of force development in Tg skinned muscle strips

All mechanical experiments were performed on skinned LVPM fibers of approximately ~1.5 mm in length and ~100 μm in diameter. The small muscle strips were attached by tweezer clips to the force transducer of the Guth Muscle Research System (Heidelberg, Germany) and then skinned in 1% Triton X-100 dissolved in pCa 8 buffer for 30 min (in a 1 ml cuvette). Next, muscle fibers were washed in pCa 8 buffer (3 times x 5 min), and their sarcomere length was adjusted to 2.1-2.2 μm. LVPM fibers were then placed in pCa 4 solution (composition is the same as pCa 8 buffer except for the [Ca

2+] = 10

-4 M) to test maximal steady-state force development and then relaxed in pCa 8 solution. To determine the force–pCa dependence, the muscle strips were exposed to solutions of increasing Ca

2+ concentration from pCa 8 to pCa 4, and the level of force was measured in each “pCa” solution. Maximal tension readings (in pCa 4) were taken before and after the force-pCa curve, averaged, then divided by the cross-sectional area of fibers and expressed in kN/m

2. The diameter of fibers was estimated using an SZ6045 Olympus microscope, with the measurement taken at 3 points along the fiber length and averaged. Force-pCa data were analyzed using the Hill equation yielding the pCa

50 (free Ca

2+ concentration which produces 50% of the maximal force; represents the measure of Ca

2+ sensitivity of force) and n

H (Hill coefficient; the measure of myofilament cooperativity) for LVPM from Tg-WT ELC, Tg-E143K ELC, Tg-WT RLC and Tg-D94A RLC mice, as described previously [

11,

20,

24].

2.3.4. Mant-ATP chase experiments

LVPM fibers from Tg-WT ELC, Tg-E143K ELC, Tg-WT RLC and Tg-D94A RLC mice reconstituted with recombinant RLC proteins were subjected to measurements of the SRX state of myosin using ATP turnover measurements, as previously described [

12,

30]. The fluorescent N-methylanthraniloyl (mant)-ATP was exchanged for nonfluorescent (dark) ATP in skinned LVPM fibers from all groups of mice using the IonOptix instrumentation. The experiment was initiated with the incubation of fibers with 250 μM mant-ATP (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in a rigor solution [120 mM KPr, 5 mM MgPr, 2.5 mM K

2HPO

4, 2.5 mM KH

2PO

4, 50 mM 3-(n-morpholino) propanesulfonic acid (MOPS), pH 6.8, and fresh 2 mM DTT] until maximum fluorescence reached a plateau. Then, mant-ATP was chased with 4 mM unlabeled ATP (in rigor buffer), resulting in fluorescence decay as hydrolyzed mant-ATP was exchanged for dark ATP. Fluorescence intensity isotherms were collected over time and were subsequently fitted to a two-exponential decay equation:

Using a nonlinear least-squares algorithm in GraphPad PRISM version 7 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA), we derived the amplitudes of the fast (P1) and slow (P2) phases of fluorescence decay and their respective T1 and T2 lifetimes (in seconds) [

11,

12,

20,

24]. P1 and T1 represent the initial fast decay in fluorescence intensity and describe the myosin in the DRX state and the release of nonspecifically bound mant-ATP, which is presumably also fast, while P2 and T2 are associated with the slow decrease in fluorescence intensity due to myosin in the SRX state [

31]. The P1 phase of the fluorescence decay was corrected for the fast release of nonspecifically bound mant-ATP in the sample and was derived experimentally using a competition assay, as described in [

30]. The fraction of nonspecifically bound mant-ATP was established as 0.44±0.02, and the amount of myosin heads directly occupying the SRX state was calculated as P2/(1-0.44) [

30].

2.4. Treatment of skinned muscle strips with Omecamtiv Mecarbil (OM)

In separate sets of experiments, native LVPM fibers from Tg mice were subjected to treatment with a myosin activator, Omecamtiv Mecarbil (OM) (APExBIO Technology LLC, Houston, TX, USA) versus placebo. All steps/reactions were carried out with the muscle strips either attached to the arms of a force transducer or freely floating in a 96-well plate. Glycerinated LVPM strips were rinsed several times in the pCa 8 solution and then skinned with 1% Triton X-100 dissolved in pCa 8 solution for 30 min, followed by washing in pCa 8 buffer. For fibers undergoing force–pCa measurements, the maximal force (pCa4) was determined first. Then fibers were subjected to treatment with 3 µM OM in pCa 8 buffer or placebo (pCa 8) for 25 minutes at room temperature. Maximal tension determination and the force-pCa dependence were done before and after OM treatment, as described in section 2.3.3. For ATP turnover experiments, the fibers were incubated with 250 μM mant-ATP in a rigor solution ±3 µM OM for 25 min at room temperature. The mant-ATP chase experiment was performed in the presence and absence of 3 µM OM as described in section 2.3.4.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All values are shown as means ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance (p<0.05) was determined using Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (GraphPad PRISM software version 7.0 for Windows).

3. Results

3.1. Effect of phosphomimetic S15D-RLC on force measurements in LVPM fibers from Tg-ELC mouse model of RCM

Here, we aimed to investigate the effects of the phosphomimetic S15D-RLC variant on cardiac muscle contraction when reconstituted in skinned LVPM strips from the Tg mouse model of RCM. As we showed recently, the myocardium of Tg-E143K ELC mic was poorly phosphorylated and this low level of RLC phosphorylation coincided with abnormal myocardial function in this RCM model [

4,

25]. LVPM fibers from Tg-E143K ELC mice, along with Tg-WT ELC control, were depleted of endogenous RLC and reconstituted with recombinant S15D-RLC or WT-RLC proteins. The efficiency of depletion/reconstitution was tested on SDS-PAGE (

Figure S1A), and the results are presented in

Figure S1B. As published previously [

8,

12,

20,

28,

29,

32,

33,

34], we could successfully remove endogenous cardiac RLC from LVPM fibers and efficiently reconstitute them with the RLC mutant of choice (

Figure S1).

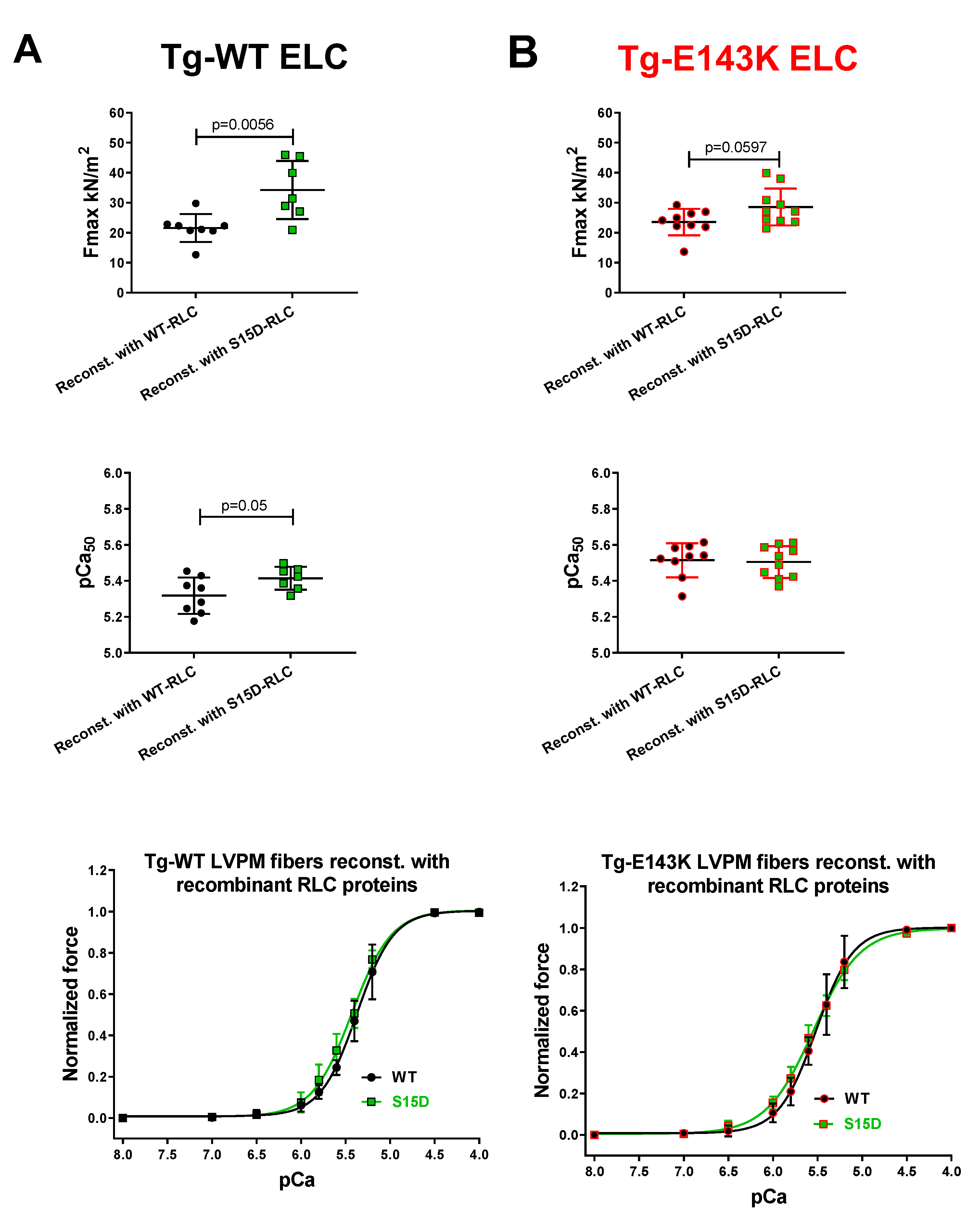

Maximal isometric force per cross-section of muscle (in kN/m

2) and pCa

50 measured for LVPM from Tg-WT ELC mice reconstituted with recombinant S15D-RLC protein were significantly higher compared with WT-RLC reconstituted (

Figure 1A,

Table 1). This result is consistent with a previously observed RLC phosphorylation-mediated increase in Ca

2+ sensitivity of contraction [

14,

35]. For LVPM fibers from Tg-E143K mice, Fmax and pCa

50 were similar between S15D-RLC and WT-RLC reconstituted, but a significant difference between WT and S15D mutant was observed for the Hill coefficient, n

H (

Figure 1B,

Table 1). The lack of an increase in the calcium sensitivity of force for LVPM fibers from RCM-E143K mutant reconstituted with S15D-RLC versus WT-RLC was most likely due to the higher Ca

2+-sensitivity observed in LVPM from Tg-E143K (5.51±0.09) versus Tg-WT ELC (5.32±0.1) reconstituted with WT-RLC and the addition of phosphomimetic S15D-RLC did not further increase calcium sensitivity of force in the RCM mutant fibers (

Table 1).

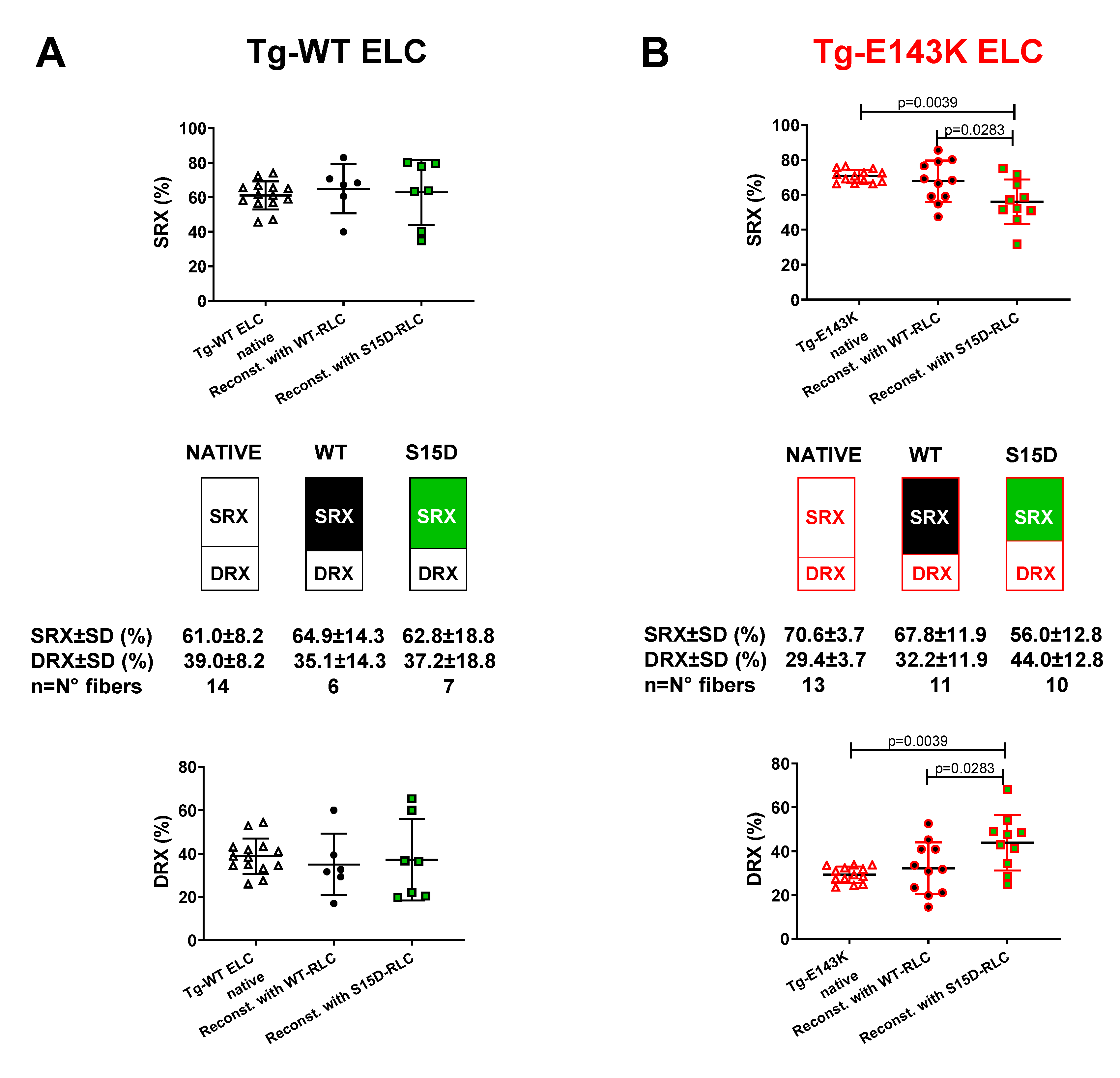

3.2. Effect of phosphomimetic S15D-RLC on super-relaxed state in LVPM fibers from Tg-ELC and Tg-RLC mouse modes of RCM and DCM.

Under resting muscle conditions, cardiac myosin can be characterized by two states, a disordered relaxed state (DRX), and a super-relaxed state (SRX) [

31]. In DRX, myosin cross-bridges protrude into the interfilament space but are restricted from binding to thin filaments and producing force. In SRX, they display an asymmetrical head arrangement along the thick filament axis and a highly inhibited ATP turnover rate [

36,

37]. The presence of the folded state of myosin, where the heads interact with each other and with the S2 part of myosin heavy chain (MHC) forming an interacting head motif (IHM), is thought to structurally underlie the biochemical SRX state.

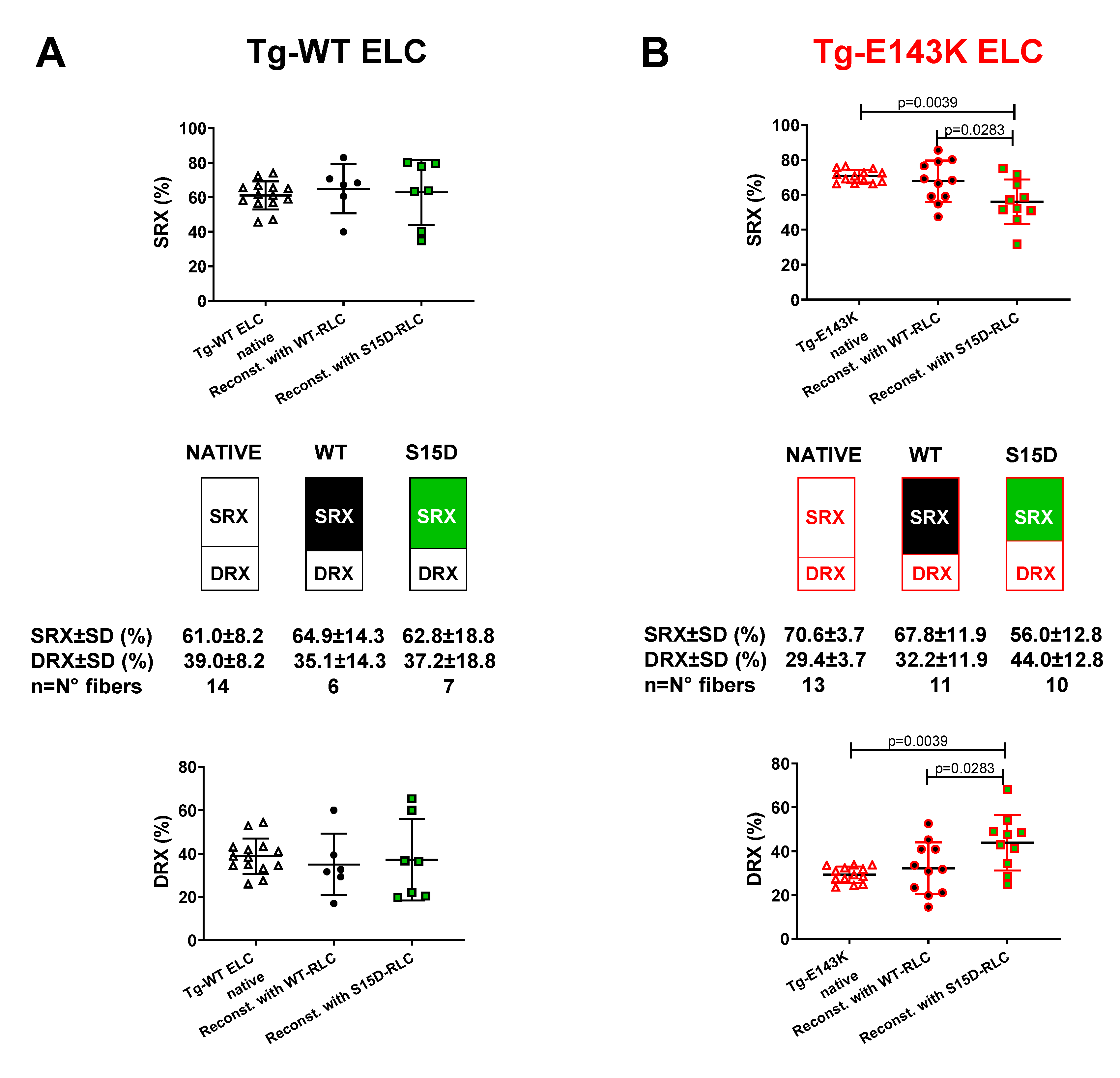

3.2.1. Transgenic ELC mice

To study the SRX state and SRX↔DRX equilibrium in reconstituted LVPM fibers from Tg-E143K ELC versus Tg-WT ELC mice, fibers were incubated in a solution containing 250 µM mant-ATP until the fluorescence intensity stabilized [

20,

30]. Then, upon addition of non-labeled ATP (4 mM), fluorescence decay curves versus time were collected and fitted to a two-state exponential equation as described is section 2.3.4. No differences were recorded on S15D-RLC versus WT-RLC in Tg-WT ELC animals (

Figure 2A,

Table 2). However, as expected, LVPM from Tg-E143K mice decreased % SRX heads upon reconstitution with the phosphomimetic S15D-RLC compared with WT-RLC reconstituted (

Figure 2B,

Table 2). Therefore, the pseudo-phosphorylation of poorly phosphorylated RLCs in Tg-E143K preparations promoted a shift in SRX↔DRX equilibrium toward DRX, making more heads available for muscle contraction compared with WT-RLC reconstituted.

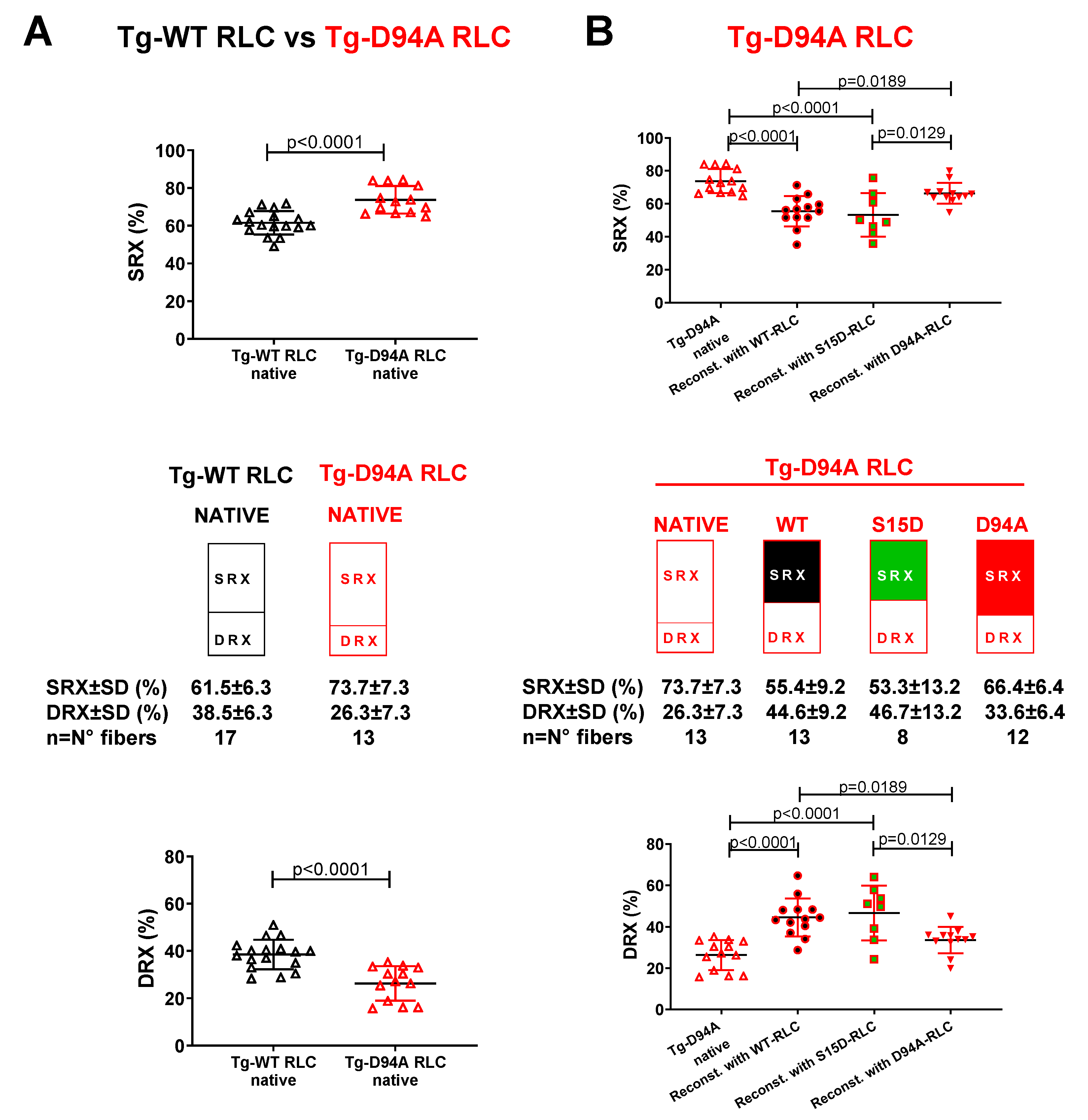

3.2.2. Transgenic RLC mice

We have recently shown the beneficial effect of the phosphomimetic S15D-RLC variant when reconstituted in LVPM fibers preparations from HCM-RLC models of cardiomyopathy [

12,

20,

28]. Here, we aimed to test whether S15D-RLC may rescue some DCM-related abnormalities when reconstituted in fibers from the DCM RLC model, Tg-D94A mice. In particular, we investigated whether the abnormal SRX/DRX ratio found in this Tg-D94A model previously [

30] could return to normal when the endogenous RLC was replaced by recombinant phosphomimetic S15D-RLC protein. LVPM from Tg-D94A mice were depleted of endogenous RLC and reconstituted with recombinant S15D-RLC, and the results were compared to native, WT, or D94A -RLC reconstituted fibers (

Figure 3,

Table 3). As observed earlier [

30], LVPM from native Tg-D94A RLC mice demonstrated ~73% myosin heads in the SRX state (

Figure 3A), indicating that DCM heads favor the energy conserving SRX state. Tg-D94A LVPM fibers reconstituted with S15D-RLC protein showed a significant decrease in % of SRX heads (53.3±13.2) compared with native (73.7±7.3) or D94A (66.4±6.4) reconstituted fibers (

Figure 3B,

Table 3). There was no difference in % heads occupying the SRX state between S15D-RLC and WT-RLC (55.1±10.2) reconstituted fibers (

Figure 3B), suggesting that phosphorylatable WT-RLC is also able to rescue the DCM-induced SRX phenotype.

3.3. Treatment of RCM and DCM mice with Omecamtiv Mecarbil (OM).

In another series of experiments, we applied Omecamtiv Mecarbil (OM), a positive cardiac inotrope, to skinned LVPM fibers from mice and tested its effect on Ca

2+-activated muscle contraction and on the SRX-to-DRX ratio in resting cardiac muscle. The drug was developed to treat systolic heart failure by targeting the cardiac MHC to increase myocardial contractility [

38]. OM has been shown to improve cardiac function in patients with heart failure (HF) with a reduced ejection fraction, and among patients who received OM, a lower incidence of a heart failure event or death than those who received a placebo was observed [

39]. Research studies on OM showed that the drug could prolong actomyosin attachment and increase the myocardial force by cooperative thin-filament activation [

40]. It was also shown that OM’s ability to increase cardiac force production may depend on the phosphorylation of myosin-binding protein C [

41].

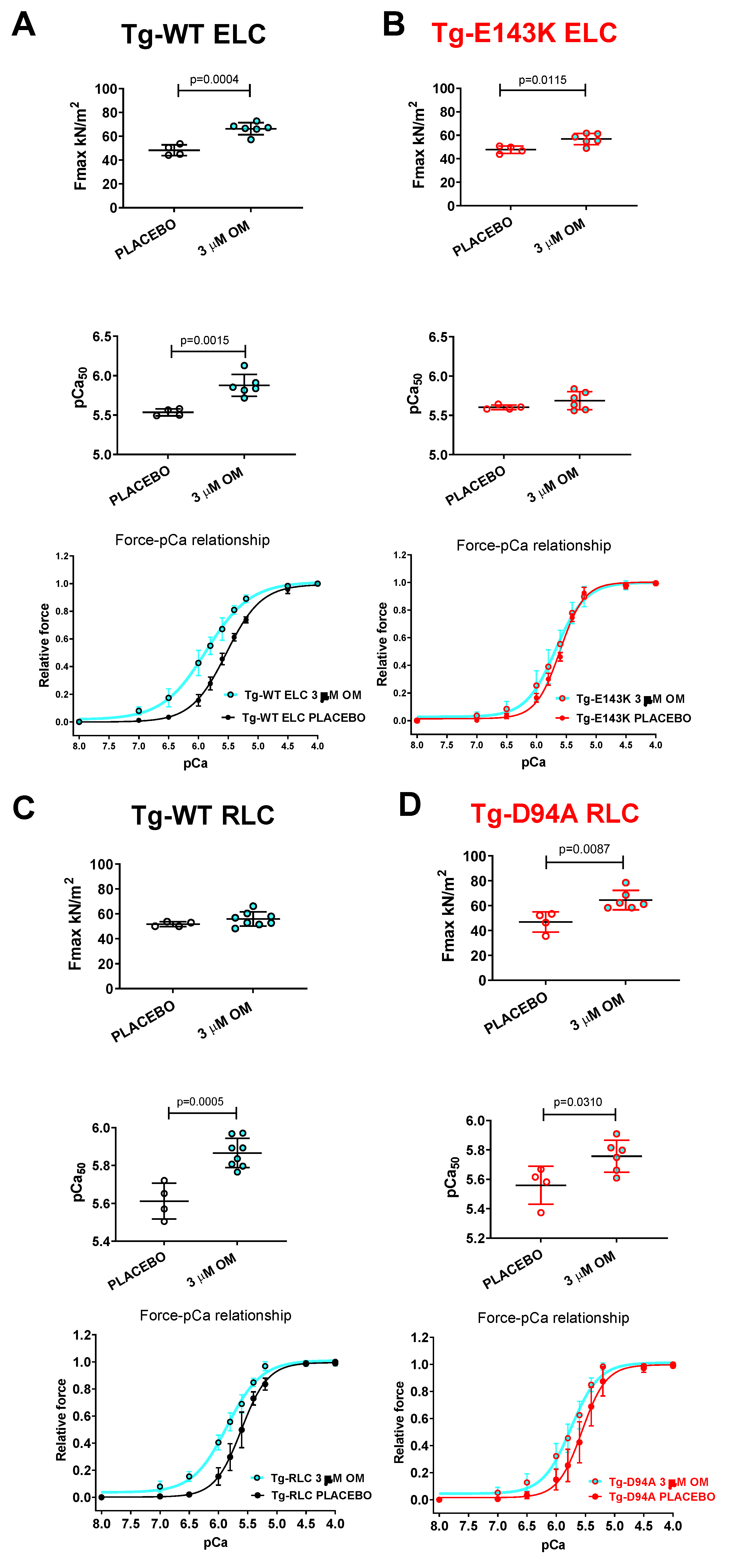

3.3.1. Steady-state force and force-pCa relationship

LVPM isolated from all Tg mouse models were subjected to treatment with 3 µM OM, and the results were compared with fibers treated with placebo (pCa 8 buffer). Exposure of LVPM fibers from Tg-WT ELC and Tg-E143K ELC mice to OM resulted in significantly higher maximal isometric force per cross-section of muscle (in kN/m

2) (

Figure 4AB,

Table 4). Additionally, the treatment with OM resulted in a significantly higher calcium sensitivity (larger pCa

50) of force for Tg-WT ELC, while no change was observed for Tg-E143K ELC mice (

Figure 4AB,

Table 4).

On the other hand, treatment with 3 µM OM of LVPM fibers from Tg-D94A RLC mice resulted in significantly higher maximal pCa 4 force per cross-section of muscle fibers and higher Ca

2+ sensitivity of force in Tg-WT RLC and Tg-D94A RLC mice compared with placebo-treated fibers (

Figure 4CD,

Table 4).

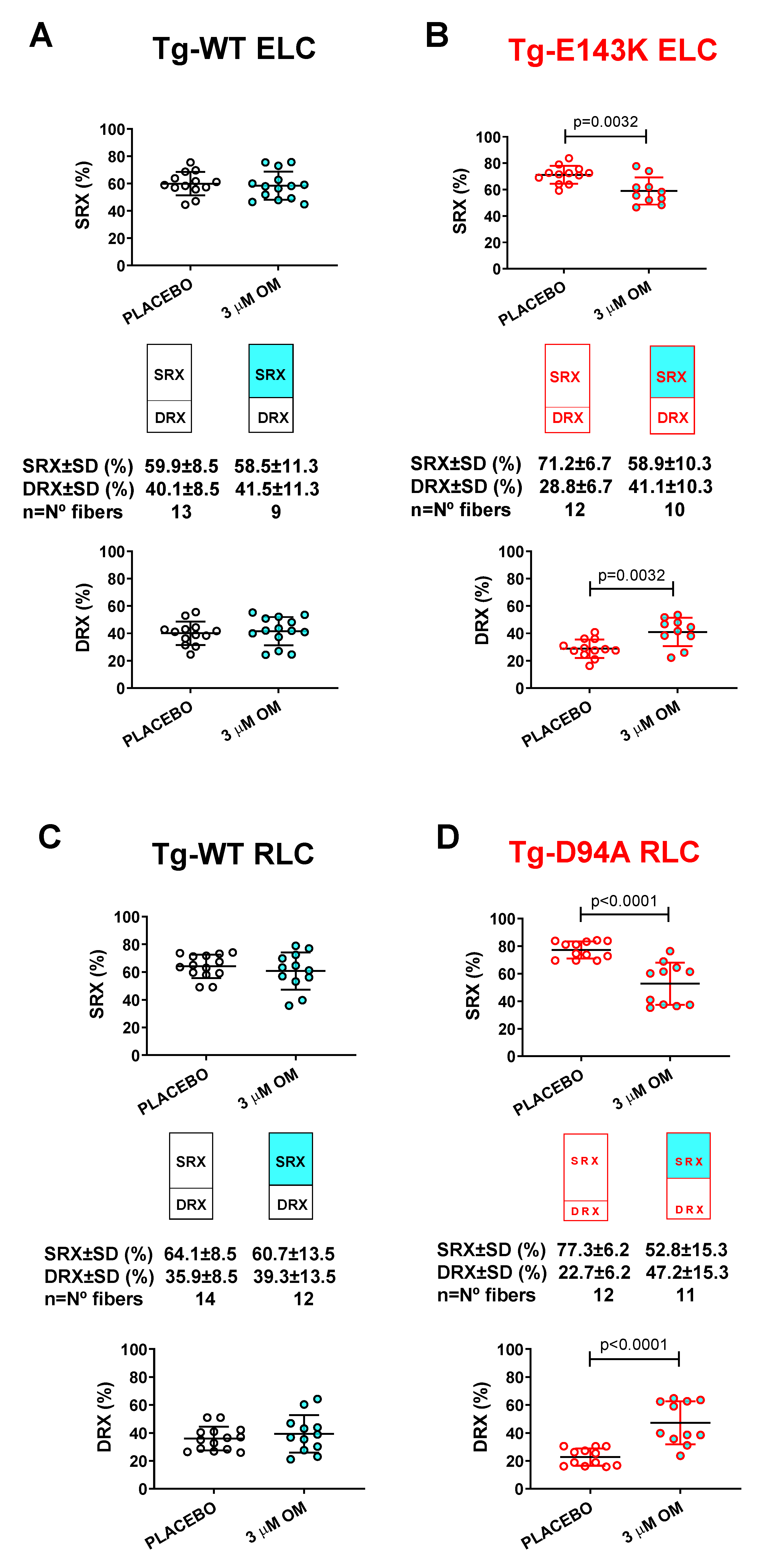

3.3.2. SRX↔DRX equilibrium in LVPM fibers from RCM and DCM mice

Next, we tested the effect of treatment with 3 µM OM of LVPM fibers from Tg RCM and DCM mouse models and their respective Tg-WT mice and the balance between the SRX and DRX states in treated versus placebo (pCa 8 buffer) (

Figure 5). Despite significant effects of OM on muscle contraction in transgenic WT-ELC and WT-RLC mice (

Figure 4AC), no effect upon treatment with OM versus placebo was observed in relaxed muscle fibers, which maintained their SRX-to-DRX ratios unchanged (

Figure 5AC,

Table 5). However, LVPM from RCM-ELC and DCM-RLC mutant mice demonstrated a significantly lower % of the SRX heads with OM treatment compared with placebo-treated fibers (

Figure 5BD,

Table 5). As we showed previously, both models, Tg-E143K ELC and Tg-D94A RLC, favored the energy conservation SRX state where myosin heads cycled ATP with highly inhibited rates [

26,

30]. In both models, treatment with 3 µM OM produced a switch from the SRX to the DRX state, where more myosin heads become disordered relaxed, and readily available for interaction with actin and force production (

Table 5). These results indicated a drug-related rescue of the RCM-E143K ELC (

Figure 5B) and DCM-D94A RLC (

Figure 5D) SRX phenotypes.

4. Discussion

Myosin RLC phosphorylation is a critical determinant of myosin motor function and heart performance in normal healthy hearts and plays an especially important role in cardiomyopathy. Genetic mutations in sarcomeric proteins, including cardiac myosin RLC and ELC, have been implicated in familial cardiomyopathies, and many of them lower myosin phosphorylation occurring at the N-terminus of myosin RLC (Ser-15) [

10,

42,

43,

44]. Pseudo-phosphorylation of myosin RLC by substituting Asp acid for Ser-15 has been widely used

in vitro and

in vivo as a genetic approach to normalizing RLC phosphorylation [

45]. Our lab has demonstrated several studies where the pseudo-phosphorylated variant (S15D) of the human ventricular RLC was able to rescue heart function in cardiomyopathy mice [

11,

21] and in reconstituted LVPM systems [

12,

20,

28]. Still, little is known about the primary mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of RLC phosphorylation. We hypothesized that one of the mechanisms involves the regulation of the myosin’s super-relaxed state, which is considered central to modulating sarcomeric force production and energy utilization in cardiac muscle [

46]. Particularly, we hypothesized that mutation-specific redistribution of myosin energetic states and abnormal SRX↔DRX equilibrium is one of the key mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of HCM, RCM, or DCM, and successful therapy should target anomalous SRX/DRX ratio.

We have recently shown the beneficial effect of phosphomimetic S15D-RLC when reconstituted in LVPM fibers from Tg-R58Q RLC and Tg-D166V RLC mice [

12,

20,

28]. In the current report, we aimed to test whether S15D-RLC may rescue RCM-related Tg-E143K ELC and DCM-related Tg-D94A RLC phenotypes when reconstituted in fibers from mice. We demonstrated that LVPM from Tg-E143K mice decreased % SRX heads upon reconstitution with the phosphomimetic S15D-RLC compared with WT-RLC reconstituted. Similarly, the abnormal SRX/DRX ratio found in this Tg-D94A RLC model previously [

30] returned to normal when the endogenous RLC was replaced by recombinant phosphomimetic S15D-RLC protein. Therefore, the pseudo-phosphorylation of RLCs in the RCM-ELC and DCM-RLC models promoted a shift in SRX↔DRX equilibrium toward the DRX state, making more heads available for muscle contraction compared with WT-RLC reconstituted, highlighting the rescue potential of phosphomimetic S15D-RLC variant.

The effects of the phosphomimetic S15D-RLC were also compared to Omecamtiv Mecarbil, a positive cardiac inotrope, testing its effect on Ca

2+-activated muscle contraction and the SRX-to-DRX ratio in resting cardiac muscle. In accord with experiments targeting cardiac myosin contractility [

38], the exposure of LVPM fibers from Tg-WT ELC and Tg-E143K ELC mice to OM resulted in significantly higher maximal isometric force per cross-section of muscle and significantly higher calcium sensitivity of force in Tg-WT ELC mice. A similar effect was observed in OM-treated LVPM fibers from Tg-D94A RLC mice, where significantly higher maximal pCa 4 force per cross-section of muscle and higher Ca

2+ sensitivity of force in Tg-WT RLC and Tg-D94A RLC mice were measured.

Similarly to the reconstitution of LVPM with S15D-RLC, treatment with 3 µM OM caused a shift from the super-relaxed state to the disordered relaxed state in RCM-E143K ELC and DCM-D94A RLC myocardium. Both models favored the energy conservation SRX state where myosin heads cycled ATP with highly inhibited rates [

26,

30]. Treatment with the drug produced more myosin heads occupying the DRX state and decreased the number of slowly cycling SRX heads, indicating a drug-related rescue of the RCM-E143K ELC and DCM-D94A RLC phenotypes.

Our collected results suggest that the number of functionally accessible myosin cross-bridges for their interaction with actin is the major determinant of the power output and different disease-causing mutations may differently impact the equilibrium between the ON↔OFF states. Clinical phenotypes associated with different cardiomyopathies discussed in this report are expected to be improved following the S15D-RLC or OM treatment. Biochemical destabilization of the SRX with both therapeutic agents is anticipated to enhance myosin activity via increasing the rate of ATP turnover and accelerating Pi release, which is the rate-limiting step in the actin-myosin ATPase cycle. Destabilizing the SRX state would lead to an increased number of myosin heads that bind to actin in a force-producing state.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: Representative SDS-PAGE of RLC-depleted and mutant RLC-reconstituted LVPM preparations from Tg-WT ELC, Tg-E143K ELC, and Tg-D94A RLC mice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, supervision, project administration and visualization, K.K. and D.S.-C., investigation, J.L., K.K., L.G.M. and N.K.S., validation, formal analysis, K.K., D.S.-C., L.G.M. and N.K.S., writing—original draft preparation, K.K.; writing, review and editing D.S.-C.; funding acquisition, D.S.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant numbers R01-HL143830 and R56-HL146133] to D.S.C.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All animal studies were conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines and the protocol was reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine (UMMSM) (protocol 21-106, approved 6/25/2021). UMMSM has an Animal Welfare Assurance (A-3224-01, approved through November 30, 2023) on file with the Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare (OLAW), National Institutes of Health. Mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation that was followed by cervical dislocation.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to Deonte Farmer-Walton for help in SRX reconstitution experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Geeves, M. A.; Holmes, K. C. , The molecular mechanism of muscle contraction. Adv Protein Chem 2005, 71, 161–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKillop, D.; Geeves, M. Regulation of the interaction between actin and myosin subfragment 1: evidence for three states of the thin filament. Biophys. J. 1993, 65, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunello, E.; Fusi, L.; Ghisleni, A.; Park-Holohan, S.-J.; Ovejero, J.G.; Narayanan, T.; Irving, M. Myosin filament-based regulation of the dynamics of contraction in heart muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 8177–8186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Yuan, C.-C.; Kazmierczak, K.; Szczesna-Cordary, D.; Burghardt, T.P. Single cardiac ventricular myosins are autonomous motors. Open Biol. 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, J.P.; Debold, E.P.; Ahmad, F.; Armstrong, A.; Frederico, A.; Conner, D.A.; Mende, U.; Lohse, M.J.; Warshaw, D.; Seidman, C.E.; et al. Cardiac myosin missense mutations cause dilated cardiomyopathy in mouse models and depress molecular motor function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006, 103, 14525–14530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcalai, R.; Seidman, J.G.; Seidman, C.E. Genetic Basis of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: From Bench to the Clinics. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2008, 19, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burghardt, T.P.; Sikkink, L.A. Regulatory Light Chain Mutants Linked to Heart Disease Modify the Cardiac Myosin Lever Arm. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 1249–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Liang, J.; Yuan, C.-C.; Kazmierczak, K.; Zhou, Z.; Morales, A.; McBride, K.L.; Fitzgerald-Butt, S.M.; Hershberger, R.E.; Szczesna-Cordary, D. Novel familial dilated cardiomyopathy mutation inMYL2affects the structure and function of myosin regulatory light chain. FEBS J. 2015, 282, 2379–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Szczesna-Cordary, D. Molecular mechanisms of cardiomyopathy phenotypes associated with myosin light chain mutations. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 2015, 36, 433–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthu, P.; Kazmierczak, K.; Jones, M.; Szczesna-Cordary, D. The effect of myosin RLC phosphorylation in normal and cardiomyopathic mouse hearts. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2012, 16, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.-C.; Muthu, P.; Kazmierczak, K.; Liang, J.; Huang, W.; Irving, T.C.; Kanashiro-Takeuchi, R.M.; Hare, J.M.; Szczesna-Cordary, D. Constitutive phosphorylation of cardiac myosin regulatory light chain prevents development of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E4138–E4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, S.; Kazmierczak, K.; Liang, J.; Sitbon, Y.H.; Szczesna-Cordary, D. Phosphomimetic-mediated in vitro rescue of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy linked to R58Q mutation in myosin regulatory light chain. FEBS J. 2018, 286, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sitbon, Y.H.; Kazmierczak, K.; Liang, J.; Yadav, S.; Veerasammy, M.; Kanashiro-Takeuchi, R.M.; Szczesna-Cordary, D. Ablation of the N terminus of cardiac essential light chain promotes the super-relaxed state of myosin and counteracts hypercontractility in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutant mice. FEBS J. 2020, 287, 3989–4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeney, H.L.; Bowman, B.F.; Stull, J.T. Myosin light chain phosphorylation in vertebrate striated muscle: regulation and function. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 1993, 264, C1085–C1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E Kamm, K.; Stull, J.T. The Function of Myosin and Myosin Light Chain Kinase Phosphorylation in Smooth Muscle. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1985, 25, 593–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamm, K.E.; Stull, J.T. Signaling to Myosin Regulatory Light Chain in Sarcomeres. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 9941–9947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seguchi, O.; Takashima, S.; Yamazaki, S.; Asakura, M.; Asano, Y.; Shintani, Y.; Wakeno, M.; Minamino, T.; Kondo, H.; Furukawa, H.; et al. A cardiac myosin light chain kinase regulates sarcomere assembly in the vertebrate heart. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 2812–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, M.; Walker, D.D.; Ferrari, M.B. Protein Phosphatase Activity Is Necessary for Myofibrillogenesis. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2006, 45, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, A.N.; Battiprolu, P.K.; Cowley, P.M.; Chen, G.; Gerard, R.D.; Pinto, J.R.; Hill, J.A.; Baker, A.J.; Kamm, K.E.; Stull, J.T. Constitutive Phosphorylation of Cardiac Myosin Regulatory Light Chain in Vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 10703–10716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazmierczak, K.; Liang, J.; Gomez-Guevara, M.; Szczesna-Cordary, D. Functional comparison of phosphomimetic S15D and T160D mutants of myosin regulatory light chain exchanged in cardiac muscle preparations of HCM and WT mice. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 988066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Yuan, C.-C.; Kazmierczak, K.; Liang, J.; Huang, W.; Takeuchi, L.M.; Kanashiro-Takeuchi, R.M.; Szczesna-Cordary, D. Therapeutic potential of AAV9-S15D-RLC gene delivery in humanized MYL2 mouse model of HCM. J. Mol. Med. 2019, 97, 1033–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamidi, R.; Li, J.; Gresham Kenneth, S.; Verma, S.; Doh Chang, Y.; Li, A.; Lal, S.; dos Remedios Cristobal, G.; Stelzer Julian, E. , Dose-Dependent Effects of the Myosin Activator Omecamtiv Mecarbil on Cross-Bridge Behavior and Force Generation in Failing Human Myocardium. Circulation: Heart Failure 2017, 10, (10), e004257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teerlink, J. R.; Felker, G. M.; McMurray, J. J.; Ponikowski, P.; Metra, M.; Filippatos, G. S.; Ezekowitz, J. A.; Dickstein, K.; Cleland, J. G.; Kim, J. B.; Lei, L.; Knusel, B.; Wolff, A. A.; Malik, F. I.; Wasserman, S. M.; Investigators, A.-A. , Acute Treatment With Omecamtiv Mecarbil to Increase Contractility in Acute Heart Failure: The ATOMIC-AHF Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016, 67, (12), 1444–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.-C.; Kazmierczak, K.; Liang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Yadav, S.; Gomes, A.V.; Irving, T.C.; Szczesna-Cordary, D. Sarcomeric perturbations of myosin motors lead to dilated cardiomyopathy in genetically modified MYL2 mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E2338–E2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, C.-C.; Kazmierczak, K.; Liang, J.; Kanashiro-Takeuchi, R.; Irving, T.C.; Gomes, A.V.; Wang, Y.; Burghardt, T.P.; Szczesna-Cordary, D. Hypercontractile mutant of ventricular myosin essential light chain leads to disruption of sarcomeric structure and function and results in restrictive cardiomyopathy in mice. Cardiovasc. Res. 2017, 113, 1124–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sitbon, Y.H.; Diaz, F.; Kazmierczak, K.; Liang, J.; Wangpaichitr, M.; Szczesna-Cordary, D. Cardiomyopathic mutations in essential light chain reveal mechanisms regulating the super relaxed state of myosin. J. Gen. Physiol. 2021, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szczesna, D.; Ghosh, D.; Li, Q.; Gomes, A.V.; Guzman, G.; Arana, C.; Zhi, G.; Stull, J.T.; Potter, J.D. Familial Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Mutations in the Regulatory Light Chains of Myosin Affect Their Structure, Ca2+Binding, and Phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 7086–7092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthu, P.; Liang, J.; Schmidt, W.; Moore, J.R.; Szczesna-Cordary, D. In vitro rescue study of a malignant familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy phenotype by pseudo-phosphorylation of myosin regulatory light chain. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2013, 552-553, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, K.; Watt, J.; Greenberg, M.; Jones, M.; Szczesna-Cordary, D.; Moore, J.R. Removal of the cardiac myosin regulatory light chain increases isometric force production. FASEB J. 2009, 23, 3571–3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C. C.; Kazmierczak, K.; Liang, J.; Ma, W.; Irving, T. C.; Szczesna-Cordary, D. , Molecular basis of force-pCa relation in MYL2 cardiomyopathy mice: Role of the super-relaxed state of myosin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022, 119, (8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooijman, P.; Stewart, M. A.; Cooke, R. , A new state of cardiac Myosin with very slow ATP turnover: a potential cardioprotective mechanism in the heart. Biophys J 2011, 100, (8), 1969–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczesna-Cordary, D.; Guzman, G.; Ng, S.-S.; Zhao, J. Familial Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy-linked Alterations in Ca2+ Binding of Human Cardiac Myosin Regulatory Light Chain Affect Cardiac Muscle Contraction. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 3535–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthu, P.; Huang, W.; Kazmierczak, K.; Szczesna-Cordary, D., Functional Consequences of Mutations in the Myosin Regulatory Light Chain Associated with Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. In: Veselka J (Ed.) 2012, Cardiomyopathies – From Basic Research to Clinical Management. Ch. 17. InTech, Croatia, pp 383-408.

- Greenberg, M.J.; Kazmierczak, K.; Szczesna-Cordary, D.; Moore, J.R. Cardiomyopathy-linked myosin regulatory light chain mutations disrupt myosin strain-dependent biochemistry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 17403–17408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulcastro, H.C.; Awinda, P.O.; Breithaupt, J.J.; Tanner, B.C. Effects of myosin light chain phosphorylation on length-dependent myosin kinetics in skinned rat myocardium. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2016, 601, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alamo, L.; Ware, J. S.; Pinto, A.; Gillilan, R. E.; Seidman, J. G.; Seidman, C. E.; Padron, R. , Effects of myosin variants on interacting-heads motif explain distinct hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy phenotypes. Elife 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodhead, J.L.; Zhao, F.-Q.; Craig, R.; Egelman, E.H.; Alamo, L.; Padrón, R. Atomic model of a myosin filament in the relaxed state. Nature 2005, 436, 1195–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, F.I.; Hartman, J.J.; Elias, K.A.; Morgan, B.P.; Rodriguez, H.; Brejc, K.; Anderson, R.L.; Sueoka, S.H.; Lee, K.H.; Finer, J.T.; et al. Cardiac Myosin Activation: A Potential Therapeutic Approach for Systolic Heart Failure. Science 2011, 331, 1439–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teerlink, J. R.; Diaz, R.; Felker, G. M.; McMurray, J. J. V.; Metra, M.; Solomon, S. D.; Adams, K. F.; Anand, I.; Arias-Mendoza, A.; Biering-Sørensen, T.; Böhm, M.; Bonderman, D.; Cleland, J. G. F.; Corbalan, R.; Crespo-Leiro, M. G.; Dahlström, U.; Echeverria, L. E.; Fang, J. C.; Filippatos, G.; Fonseca, C.; Goncalvesova, E.; Goudev, A. R.; Howlett, J. G.; Lanfear, D. E.; Li, J.; Lund, M.; Macdonald, P.; Mareev, V.; Momomura, S. I.; O'Meara, E.; Parkhomenko, A.; Ponikowski, P.; Ramires, F. J. A.; Serpytis, P.; Sliwa, K.; Spinar, J.; Suter, T. M.; Tomcsanyi, J.; Vandekerckhove, H.; Vinereanu, D.; Voors, A. A.; Yilmaz, M. B.; Zannad, F.; Sharpsten, L.; Legg, J. C.; Varin, C.; Honarpour, N.; Abbasi, S. A.; Malik, F. I.; Kurtz, C. E. , Cardiac Myosin Activation with Omecamtiv Mecarbil in Systolic Heart Failure. N Engl J Med 2021, 384, (2), 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woody, M.S.; Greenberg, M.J.; Barua, B.; Winkelmann, D.A.; Goldman, Y.E.; Ostap, E.M. Positive cardiac inotrope omecamtiv mecarbil activates muscle despite suppressing the myosin working stroke. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamidi, R.; Holmes, J.B.; Doh, C.Y.; Dominic, K.L.; Madugula, N.; Stelzer, J.E. cMyBPC phosphorylation modulates the effect of omecamtiv mecarbil on myocardial force generation. J. Gen. Physiol. 2021, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, T.P.; Jones, M.; Kazmierczak, K.; Liang, H.-Y.; Pinheiro, A.C.; Wagg, C.S.; Lopaschuk, G.D.; Szczesna-Cordary, D. Diastolic dysfunction in familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy transgenic model mice. Cardiovasc. Res. 2009, 82, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazmierczak, K.; Xu, Y.; Jones, M.; Guzman, G.; Hernandez, O.M.; Kerrick, W.G.L.; Szczesna-Cordary, D. The Role of the N-Terminus of the Myosin Essential Light Chain in Cardiac Muscle Contraction. J. Mol. Biol. 2009, 387, 706–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Ajtai, K.; Burghardt, T.P. Ventricular myosin modifies in vitro step-size when phosphorylated. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2014, 72, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Chakravorty, S.; Song, W.; Ferenczi, M.A. Phosphorylation of the regulatory light chain of myosin in striated muscle: methodological perspectives. Eur. Biophys. J. 2016, 45, 779–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toepfer, C.N.; Garfinkel, A.C.; Venturini, G.; Wakimoto, H.; Repetti, G.; Alamo, L.; Sharma, A.; Agarwal, R.; Ewoldt, J.K.; Cloonan, P.; et al. Myosin Sequestration Regulates Sarcomere Function, Cardiomyocyte Energetics, and Metabolism, Informing the Pathogenesis of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circ. 2020, 141, 828–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Contractile function in skinned LVPM from Tg-WT ELC (A) and Tg-E143K ELC (B) mice reconstituted with recombinant RLC proteins. Maximal force (top panels), Ca2+ sensitivity of force (middle panels) and force-pCa relationship (bottom panels) were measured in LVPM from Tg-WT ELC and Tg-E143K preparations depleted of endogenous RLC and reconstituted with recombinant WT-RLC (black filled points), S15D-RLC (green filled points) proteins. Data are the average ±SD of n = 7-8 reconstituted LVPM fibers from Tg-WT ELC (2 animals-1F, 1M) and n= 9-10 reconstituted LVPM fibers from Tg-E143K ELC (3 animals-2F, 1M). Significance (p values) was calculated by Student’s t-test.

Figure 1.

Contractile function in skinned LVPM from Tg-WT ELC (A) and Tg-E143K ELC (B) mice reconstituted with recombinant RLC proteins. Maximal force (top panels), Ca2+ sensitivity of force (middle panels) and force-pCa relationship (bottom panels) were measured in LVPM from Tg-WT ELC and Tg-E143K preparations depleted of endogenous RLC and reconstituted with recombinant WT-RLC (black filled points), S15D-RLC (green filled points) proteins. Data are the average ±SD of n = 7-8 reconstituted LVPM fibers from Tg-WT ELC (2 animals-1F, 1M) and n= 9-10 reconstituted LVPM fibers from Tg-E143K ELC (3 animals-2F, 1M). Significance (p values) was calculated by Student’s t-test.

Figure 2.

Summary of the SRX study for LVPM fibers from Tg-WT ELC (A) and Tg-E143K ELC (B) reconstituted with WT-RLC versus phosphomimetic S15D-RLC. The proportion of myosin heads in SRX state (top panels) and DRX states (bottom panels) is shown for native (clear points), WT- (black filled points), S15D- (green filled points) RLC reconstituted Tg fibers. Note that % SRX is increased in native Tg-E143K fibers compared to Tg-WT ELC native controls (~71% versus ~61%). For Tg-E143K fibers reconstituted with WT-RLC or S15D-RLC, the latter significantly decreased % of myosin heads in SRX (~56%) compared with WT-RLC reconstituted (68%) or native Tg-E143K fibers (71%). Data are expressed as mean ± SD for n=14 Tg-WT ELC native fibers (4 animals-2F, 2M); n= 6-7 (4 animals-2F, 2M) for Tg-WT ELC fibers reconstituted with WT-RLC or S15D-RLC. For Tg-E143K set, n=13 fibers for native Tg-E143K (4 animals-2F, 2M); n=10-11 fibers for Tg-E143K (5 animals-3F, 2M) reconstituted with WT-RLC or S15D-RLC were used. The significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

Figure 2.

Summary of the SRX study for LVPM fibers from Tg-WT ELC (A) and Tg-E143K ELC (B) reconstituted with WT-RLC versus phosphomimetic S15D-RLC. The proportion of myosin heads in SRX state (top panels) and DRX states (bottom panels) is shown for native (clear points), WT- (black filled points), S15D- (green filled points) RLC reconstituted Tg fibers. Note that % SRX is increased in native Tg-E143K fibers compared to Tg-WT ELC native controls (~71% versus ~61%). For Tg-E143K fibers reconstituted with WT-RLC or S15D-RLC, the latter significantly decreased % of myosin heads in SRX (~56%) compared with WT-RLC reconstituted (68%) or native Tg-E143K fibers (71%). Data are expressed as mean ± SD for n=14 Tg-WT ELC native fibers (4 animals-2F, 2M); n= 6-7 (4 animals-2F, 2M) for Tg-WT ELC fibers reconstituted with WT-RLC or S15D-RLC. For Tg-E143K set, n=13 fibers for native Tg-E143K (4 animals-2F, 2M); n=10-11 fibers for Tg-E143K (5 animals-3F, 2M) reconstituted with WT-RLC or S15D-RLC were used. The significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

Figure 3.

Summary of the SRX study performed on reconstituted LVPM fibers from the model of DCM, Tg-D94A mice. A. SRX comparison between Tg-WT RLC and Tg-D94A RLC mice. B. The proportion of myosin heads in the SRX (top) and DRX (bottom) states. LVPM reconstituted with WT-RLC are shown in black filled symbols, while S15D-RLC in green filled symbols. D94A-RLC reconstituted fibers are depicted with red filled symbols. Data are expressed as mean ± SD of n= N° fibers: n=13, 4 animals-3F, 1M for native Tg-D94A, n=17, 5 animals-2F, 3M for Tg-WT native, and n=8-13, 4 animals-1F, 3M for LVPM fibers from Tg-D94A reconstituted with RLC proteins. The significance was calculated by Student’s t-test (A) and one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (B).

Figure 3.

Summary of the SRX study performed on reconstituted LVPM fibers from the model of DCM, Tg-D94A mice. A. SRX comparison between Tg-WT RLC and Tg-D94A RLC mice. B. The proportion of myosin heads in the SRX (top) and DRX (bottom) states. LVPM reconstituted with WT-RLC are shown in black filled symbols, while S15D-RLC in green filled symbols. D94A-RLC reconstituted fibers are depicted with red filled symbols. Data are expressed as mean ± SD of n= N° fibers: n=13, 4 animals-3F, 1M for native Tg-D94A, n=17, 5 animals-2F, 3M for Tg-WT native, and n=8-13, 4 animals-1F, 3M for LVPM fibers from Tg-D94A reconstituted with RLC proteins. The significance was calculated by Student’s t-test (A) and one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (B).

Figure 4.

Contractile function in skinned LVPM fibers from Tg-WT ELC (A), Tg-E143K ELC (B), Tg-WT RLC (C), and Tg-D94A RLC (D) mice treated with 3 µM OM versus placebo (pCa 8 buffer). Maximal force (top panels), Ca2+-sensitivity of force (middle panels), and force-pCa relationships (bottom panels) were measured in fibers treated with 3 µM OM (cyan filled points) compared with placebo (pCa 8 solution) (clear points). Data are the average ± SD of n = 4-8 fibers (1-2 mice) per group. P values were calculated by Student’s t-test.

Figure 4.

Contractile function in skinned LVPM fibers from Tg-WT ELC (A), Tg-E143K ELC (B), Tg-WT RLC (C), and Tg-D94A RLC (D) mice treated with 3 µM OM versus placebo (pCa 8 buffer). Maximal force (top panels), Ca2+-sensitivity of force (middle panels), and force-pCa relationships (bottom panels) were measured in fibers treated with 3 µM OM (cyan filled points) compared with placebo (pCa 8 solution) (clear points). Data are the average ± SD of n = 4-8 fibers (1-2 mice) per group. P values were calculated by Student’s t-test.

Figure 5.

Rescue of SRX↔DRX equilibrium in LVPM from RCM-ELC and DCM-RLC mouse models treated with 3 µM OM. Fibers treated with 3 µM OM (cyan filled points) were compared with placebo-treated controls (clear points). A. Tg-WT ELC, B. Tg-E143K ELC, C. Tg-WT RLC, and D. Tg-D94A RLC mice. Data are the average ± SD of n = 9-14 fibers of 1-2 mice per group. P values were calculated by Student’s t-test.

Figure 5.

Rescue of SRX↔DRX equilibrium in LVPM from RCM-ELC and DCM-RLC mouse models treated with 3 µM OM. Fibers treated with 3 µM OM (cyan filled points) were compared with placebo-treated controls (clear points). A. Tg-WT ELC, B. Tg-E143K ELC, C. Tg-WT RLC, and D. Tg-D94A RLC mice. Data are the average ± SD of n = 9-14 fibers of 1-2 mice per group. P values were calculated by Student’s t-test.

Table 1.

Maximal tension and force-pCa relationship in LVPM from Tg-WT ELC and Tg-E143K ELC mice.

Table 1.

Maximal tension and force-pCa relationship in LVPM from Tg-WT ELC and Tg-E143K ELC mice.

Force parameter

/recombinant RLC-reconstituted LVPM |

LVPM from Tg-WT ELC mice |

LVPM from Tg-E143K mice |

| WT |

S15D |

WT |

S15D |

| N° fibers |

8 |

7 |

9 |

10 |

| Fmax (kN/m2) ± SD |

21.56±4.64 |

34.25±9.66** |

23.56±4.42 |

28.58±1.95 |

| pCa50 ± SD |

5.32±0.1 |

5.41±0.06* |

5.51±0.09 |

5.51±0.09 |

| nH ± SD |

2.03±0.74 |

1.87±0.41 |

2.2±0.61 |

1.73±0.24* |

Table 2.

The SRX state of myosin assessed in LVPM from Tg-WT ELC and Tg-E143K mice reconstituted with recombinant RLC proteins.

Table 2.

The SRX state of myosin assessed in LVPM from Tg-WT ELC and Tg-E143K mice reconstituted with recombinant RLC proteins.

| Scheme . |

LVPM from Tg-WT ELC mice |

LVPM from Tg-E143K mice |

| Native |

WT |

S15D |

Native |

WT |

S15D |

| N° fibers |

14 |

6 |

7 |

13 |

11 |

10 |

| DRX (%) ± SD |

38.9±8.2 |

35.1±14.2 |

37.2±18.8 |

29.4±3.7##

|

32.3±11.9 |

44±12.8* |

| SRX (%) ± SD |

61.1±8.2 |

64.9±14.2 |

62.8±18.8 |

70.6±3.7##

|

67.8±11.9 |

56±12.8* |

| T1 (s) ± SD |

4.4±2.4 |

6.6±4.9 |

5.3±2.5 |

4.2±2.5 |

4.8±3.6 |

7±5.2 |

| T2 (s) ± SD |

129.8±67 |

125.3±81.3 |

173.4±167.7 |

126.5±81.2 |

92.2±64 |

136.4±116.5 |

Table 3.

The SRX state of myosin assessed in LVPM from Tg-D94A mice reconstituted with recombinant RLC proteins.

Table 3.

The SRX state of myosin assessed in LVPM from Tg-D94A mice reconstituted with recombinant RLC proteins.

| SRX parameter / recombinant RLC-reconstituted LVPM |

LVPM from Tg-D94A mice |

| Native |

WT |

S15D |

D94A |

| No. fibers |

13 |

13 |

8 |

12 |

| DRX±SD |

26.3±7.3 |

44.9±10.2****, ^ |

46.7±13.2****, ^ |

33.6±6.4 |

| SRX±SD |

73.7±7.3 |

55.1±10.2****, ^ |

53.3±13.2****, ^ |

66.4±6.4 |

| T1±SD |

6.5±3.3 |

4.9±2.8 |

5.7±5.1 |

2.7±1.7* |

| T2±SD |

161.8±149 |

136.9±103.1 |

117.7±130.8 |

67.4±77.3 |

Table 4.

Maximal tension (pCa 4) and force-pCa relationship in LVPM from Tg-WT ELC, Tg-E143K ELC, Tg-WT RLC, and Tg-D94A RLC mice treated with omecamtiv mecarbil versus placebo.

Table 4.

Maximal tension (pCa 4) and force-pCa relationship in LVPM from Tg-WT ELC, Tg-E143K ELC, Tg-WT RLC, and Tg-D94A RLC mice treated with omecamtiv mecarbil versus placebo.

| Force parameter // OM vs placebo treated fibers |

LVPM from Tg-WT ELC mice |

LVPM from Tg-E143K mice |

LVPM from Tg-WT RLC mice |

LVPM from Tg-D94A mice |

| OM |

placebo |

OM |

placebo |

OM |

placebo |

OM |

placebo |

| No. fibers |

6 |

4 |

6 |

4 |

8 |

4 |

6 |

4 |

| Fmax (kN/m2) ± SD |

66.4±5.1*** |

48.3±4.5 |

56.8±4.8* |

47.8±3.2 |

55.8±5.7 |

51.7±2 |

64.5±7.8** |

46.9±8.1 |

| pCa50 ± SD |

5.9±0.1** |

5.5±0.04 |

5.7±0.1 |

5.6±0.03 |

5.9±0.1*** |

5.6±0.1 |

5.8±0.1* |

5.6±0.1 |

| nH ± SD |

1.2±0.1* |

1.5±0.2 |

1.8±0.2* |

2.2±0.1 |

1.5±0.2** |

2±0.2 |

1.9±0.3* |

2.2±0.2 |

Table 5.

The SRX state of myosin study assessed in LVPM from Tg-WT ELC, Tg-E143K ELC, Tg-WT RLC, and Tg-D94A RLC mice treated with OM versus placebo.

Table 5.

The SRX state of myosin study assessed in LVPM from Tg-WT ELC, Tg-E143K ELC, Tg-WT RLC, and Tg-D94A RLC mice treated with OM versus placebo.

| SRX parameter // OM vs placebo treated fibers |

LVPM from Tg-WT ELC mice |

LVPM from Tg-E143K mice |

LVPM from Tg-WT RLC mice |

LVPM from Tg-D94A mice |

| OM |

placebo |

OM |

placebo |

OM |

placebo |

OM |

placebo |

| No. fibers |

14 |

13 |

10 |

12 |

12 |

14 |

11 |

12 |

| DRX±SD |

41.6±10.4 |

40.1±8.5 |

41.1±10.3** |

28.8±6.7 |

39.3±13.4 |

35.9±8.5 |

47.2±15.3**** |

22.7±6.2 |

| SRX±SD |

58.4±10.4 |

59.9±8.5 |

58.9±10.3** |

71.2±6.7 |

60.7±13.4 |

64.1±8.5 |

52.8±15.3**** |

77.3±6.2 |

| T1±SD |

3.7±3.4 |

3.2±1.8 |

3.7±2.4 |

4.2±2.7 |

4.2±3 |

5.6±3.8 |

3.7±1.9* |

6.9±4.1 |

| T2±SD |

101.4±152.5 |

69±38.5 |

89.3±78.9 |

112.9±94.3 |

123.8±86.8 |

119.6±122.4 |

83.1±65.6* |

230.6±213.8 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).