1. Introduction

To achieve universal access to water and sanitation services (WSS), a substantial investment of approximately US$ 1.7 x1012 will be necessary (Hutton and Varughese, 2016), requiring a more collaborative approach where all stakeholders must play an active role (Kolker et al., 2016). Further significant investments are required to fully achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), e.g., covering water resources management and irrigation (Nagpal et al., 2018). The financing needs for WSS alone are significant, particularly considering their historical trend, however, this amount must be put into perspective, as when compared to the global economy, it represents “only” about 0.10% of low- and middle-income countries GDP (Perard, 2018).

The limited access to an adequate WSS has among its origins the misalignment of the sector's governance, represented by its public policies, institutions, and regulation (PIR), depriving the overall complementarity between policy objectives, instruments, and the wider political context, i.e., not fostering a policy coherent environment and, thus, compromising policy effectiveness (Mathieu, 2022). This situation tends to harm a favorable operating environment and not establish adequate incentives to achieve the SDGs (Mumssen et al., 2018). Particularly with infrastructure investments, an understanding of the processes that drive public spending allocations and their efficiency, is essential to ensure equitable and sustainable WSS (Manghee and Berg, 2012). The de jure reforms must turn into de facto reforms, to allow the achievement of sustainable WSS in its financial, social, and environmental dimensions (Lindberg et al., 2017). The sustainable development of WSS depends on significant investments, which are clearly not met by the current funding efforts (Machete and Marques, 2021, and OECD, 2019).

WSS governance may be defined by the institutional, political-economic, and social dimensions that organize the human influenced water cycle. Governance is the practice of interaction by actors to coordinate such cycle, to engage in political and power relations, while considering technical and planning needs, as with access to WSS (GWSP, 2021; Bolognesi et al., 2022). The concept of multi-level governance used by the OECD represents the sharing of policy making, responsibilities, development, and execution at different administrative and territorial levels (Akhmouch et al., 2017). Social structures can affect economic results, consequently organizational governance practices influence the behavior of decision makers and the ability to obtain expressive results of collective interest (Ostrom, 2010). The water sector governance challenges include considerable differences between territories, multiple actors in WSS policy, low capacity of subnational governments, fragile institutional structures, ineffective regulatory framework, and irregular financial management (Akhmouch, 2014; Marques et al. 2016).

The universalization of access to WSS, especially for the most vulnerable population, must target the inequality between and within local and regional territories, with different patterns bounded by legal or informal constraints (Cetrulo et al., 2020a). As an example, peri-urban areas and informal settlements experience a lower access to WSS, as these territories are often excluded from public policies (Mitlin and Walnycki, 2020). WSS public policies should ideally be articulated with other urban and rural development, and social progress programs, stimulating employment and income (UN, 2020). This multidisciplinary requirement is key to improving territorial resilience to unpredictable climate (Pinto et al. 2021) or pandemic stressors (Elleuch et al., 2021), as well as to mitigating the impacts from inadequate access to WSS (Novaes et al., 2022).

Water sector challenges, including governance and infrastructure, are particularly pronounced in developing economies, often reflecting and exacerbating existing inequalities. In those countries, territorial segregation may lead to asymmetric situations in terms of capacity (e.g. infrastructures and resources), where WSS do not meet the SDGs. Thus, regionalization may come as a solution, possibly leading to improvements in (Lieberherr et al., 2022): 1) Service efficiency and/or effectiveness; 2) Human resources / capacity development; 3) Accountability and participation. Point 1) by exploiting scale and scope efficiencies, improved access, equity in delivery. Point 2) by building capacity in smaller local WSS and allowing to tap into more qualified human resources. Point 3) by incorporating civil society in planning and delivery, improved transparency and accountability. Naturally, the aim is to attain a suitable scale able to facilitate investment plans, resulting in improved access and quality of WSS, particularly in smaller municipalities where such improvements would otherwise be unattainable. Those improvements hinge on the presence of robust governance principles, with operational and risk management procedures, able to enhance efficiency and effectiveness in overall management.

Brazil is an interesting case, where despite the advances promoted by, e.g., Law No. 11,445/07, the Brazilian population still faces difficulties in accessing WSS (Narzetti and Marques, 2021a, Cetrulo et al., 2020b). The overall situation of WSS is alarming and with significant asymmetries. Governmental projections (PLANSAB) indicate that Brazil would need to invest around R$26 x109 in WSS per year, around 0.4% of annual GDP, in the period 2013-2033 (MDR, 2019).

However, other studies calculate that the investments needed to universalize access to WSS would be much higher, e.g., R$ 753 x109 in the period 2018-2033, an average of R$ 47 x109 per year (KPMG and ABCON, 2020). The average investment made in the last 10 years was R$ 12 x109 per year, less than half of the volume required according to PLANSAB. In addition to the low volume of investments, financial flows are unequal and are concentrated in the southern regions, contrasting the priorities that should be the North and Northeast regions, those with the greatest deficits. The universalization of WSS would provide enormous benefits to the country, namely: on direct effects on the sector, generation of employment, income, and taxes; or from indirect benefits such as reduced health costs, increased productivity, real estate appreciation, tourism and social welfare (ExAnte, 2018). Faced with this worrying investment scenario, the population without suitable WSS amounts to almost 35 million without drinking water services, and about 100 million without sanitation services (SNIS, 2020).

The state of Santa Catarina is a particular case in Brazil, where disparities are significant. While it stands out in a series of quality-of-life indicators and has an HDI of 0.774 (UNDP, 2022), ranking third in Brazil, when it comes to WSS, it faces evident challenges. Thus, the topic of regionalization rises as a possible solution to improve WSS, e.g., allowing sustainable investments able to improve WSS accessibility, as well as regional growth and development. Thus, the research objectives are:

Assess the constraints of reaching universal access to WSS in Santa Catarina (case study), and the role of regionalization to achieve it.

Analyze the financial-economic viability of regional utilities, using a cash flow analysis and evaluating the tariff break-even point to support costs and investments to achieve universal access by 2033 (coverage: 99% water supply and 90% sanitation).

Evaluate the social impacts, namely the household commitment with WSS (affordability), and identify the need for direct or cross subsidies.

After this brief introduction, we present the methodology used to assess the viability of regional entities, followed by an empirical analysis, where the institutional and legal framework is outlined and the results are presented. This document ends with key policy implications and concluding remarks, particularly with a discussion on the need for an enabling environment through context-suitable water governance and financing pathways.

2. Methodology

2.1. The Framework: General Remarks

To evaluate the contribution of regionalization of WSS utilities towards achieving universal access, it is crucial to establish an integrated framework that comprehensively assesses their financial-economic and social sustainability. This integration allows to go beyond the “recovery of recurring opex to keep operations running” (Pinto et al., 2018) and ensure the long-term feasibility of regional utilities while promoting equitable and affordable access to WSS. The following outlines the key components of the framework:

- 1.

Financial-economic sustainability assessment:

Evaluate the financial viability of regional utilities, considering revenue streams, operational costs, and investment requirements.

Assess the efficiency of financial management, including revenue collection, cost recovery mechanisms, and budget planning.

Analyze the economic viability of services, including cost-effectiveness of service provision, and pricing mechanisms.

Analyze strategies for revenue diversification, cost optimization, and resource allocation to enhance financial stability.

- 2.

Social sustainability assessment:

Evaluate the inclusiveness and equity of service provision, considering access to services across geographic areas, income groups, and marginalized populations.

Assess WSS affordability for different income segments.

- 3.

Integrated evaluation:

Integrate findings into political decision-making, covering strategic planning and policy formulation, to foster improvements (e.g., universal access tows).

By employing this comprehensive framework, regional utilities can assess and strengthen their financial, economic, and social sustainability, ultimately working towards achieving universal coverage of water and sanitation services in an equitable, affordable, and sustainable manner.

2.2. The Financial-Economic Evaluation: Assumptions and Criteria

To effectively attain universal access to WSS, it is essential to foster diverse revenue streams as part of the enabling environment. Relying solely on traditional funding sources may prove insufficient to meet the substantial investment requirements in infrastructure, maintenance, and service provision. By exploring and promoting alternative revenue streams, we can bolster the financial sustainability of WSS systems. This multi-faceted approach to revenue generation ensures a more resilient and robust funding, supporting the long-term viability of “WSS for all”.

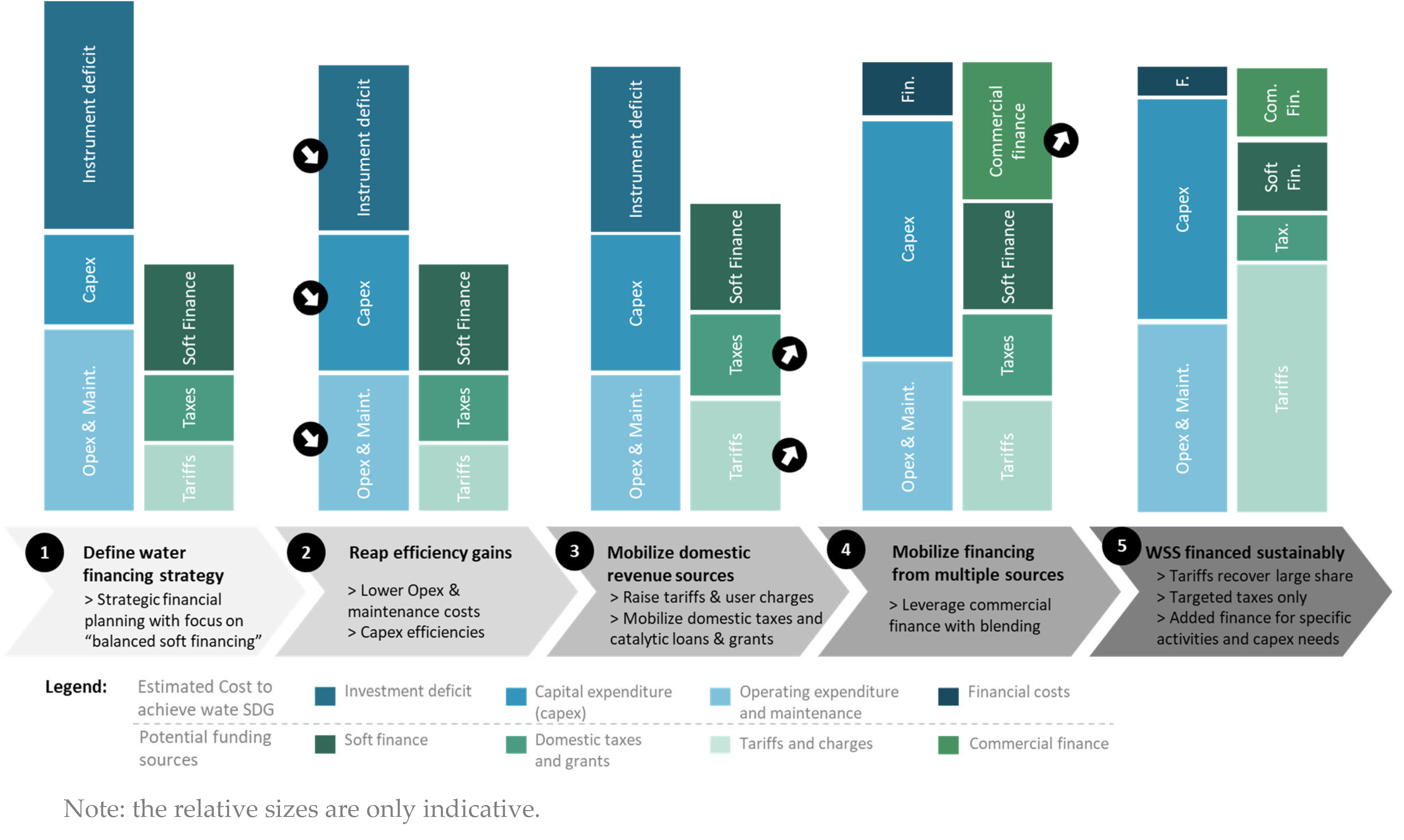

Establishing a strong connection between different costs and diverse revenue sources is vital in creating sustainable WSS (Cetrulo et al., 2019). It is crucial to align the costs associated with infrastructure development (and other capital charges), operation, maintenance, and possible opportunity costs and externalities with the corresponding revenue streams (Boukhari et al., 2020). This ensures a balance between financial obligations and available resources. By carefully analyzing cost structures and exploring revenue opportunities, we can establish a coherent financial framework that supports the affordability, quality, and accessibility of WSS for all segments of society. There is a need to ensure revenue from different sources such as tariffs, taxes, and transfers (3 Ts of OECD, 2019), as well as other streams for, e.g., investment flexibility, as loans. The devil will be in the detail, i.e., the role of cross-subsidization, the characteristics of those loans (e.g., soft loans have better interest rates, grace periods, or a combination of both), fund allowances, subsidies, grants, and targeted charges.

Figure 1 highlights the role of different revenue streams of a financing pathway to achieve water SDGs, e.g., universal access to WSS.

The financial-economic evaluation relies on a cash flow analysis, considering nominal or current year prices by default. This approach ensures that relative price changes and price level changes are appropriately accounted for. In specific instances, such as cost-benefit measurements, all values are deflated to a chosen year’s price level (Jenkins, 1978) to maintain consistency. Additionally, a “stock and flow” thinking will be employed, utilizing balance sheets and financial statements to enhance transparency and enable accurate tracking of progress and outcomes.

To adequately evaluate a utility's financial position, it is crucial to select appropriate financial-economic indicators from a comprehensive set of financial dimensions. These indicators aim to provide insights into efficiency and operational performance, creditworthiness, and liquidity, as well as profitability. However, it is important to note that while the selected indicators offer valuable information and highlight areas for further investigation, they do not alone provide definitive answers regarding the financial condition of a utility.

In

Table 1, we outline the various dimensions of financial analysis and their underlying rationale (Yepes and Dianderas, 1996). Depending on the context of each case study, such as the availability of information, a suitable set of indicators needs to be chosen. To foster a more representative picture, certain indicators, which may exhibit high volatility from year to year, might be calculated using median or average values extracted from the balance sheets and financial statements over a defined period. Ultimately, the approval of the utility's financial condition will depend on the comparison of each indicator against its respective reference value.

The cost assumptions are contingent upon the investments required to be made within a defined timeframe, particularly to achieve the targets of universalization. The coverage target must be established by considering population projections over the defined timeframe. Those projections allow to estimate the connected and unconnected households, defining the investment needed to achieve the prescribed coverage targets. This estimation accounts for the necessity of expansion to accommodate both demographic growth and the extension of coverage to areas where WSS do not yet reach. In cases where the population growth rate is zero or negative, a constant population will be assumed.

In general, the reference standards respect the assumptions of Financial-Economic balance of contracts and projects, that is, the required Total Revenue (TR*) of a certain period is the sum of Total Costs/Expenses (TC), Taxes (T), and Investment (I). The Free Cash Flow (FCF) is defined as the cash balance available to a company after considering its investments. It serves as an indicator of the company's financial position. The FCF model relies on three key categories of variables to project the cash flow: (a) revenues, (b) operating costs and taxes, and (c) investments. The analysis of the Financial-Economic model adopted observes the following:

The Net Present Value (NPV) of the project is the sum of cash flows (at present values) over the life of the project (Damodaran, 2004), thus, it allows to determine the present value of future payments discounted at an appropriate interest rate, less the cost of the initial investment. NPV represents the present value of an investment and its income (World Bank, 2013).

It is the calculation used to measure how much future payments plus an initial cost would currently be worth without neglecting the concept of the time value of money. In this regard, the cost of capital is also an important factor in the regulation of WSS. Therefore, regulators determine the cost of capital provided by investors to the utility, and then set tariffs designed to allow the company to earn its cost of capital (Brigham and Ehrhardt, 2012).

The Financial-Economic balance of a contract or project is achieved when the sum of actual FCF, discounted over time by the predetermined rate of return, equals zero. In other words, it is when the NPV reaches zero. This indicates that the TR generated is sufficient to cover all costs, expenses, taxes, and investments. If the NPV is greater than zero, it means that the expected returns from the project or contract exceed the established benchmarks. If the NPV is less than zero, it indicates that the expected returns fall below the projected/contracted requirements.

2.3. The Social Impact Evaluation: Assumptions and Criteria

Performing a comprehensive social impact evaluation of regional utilities is crucial in the pursuit of universal access to WSS. To effectively assess the social implications of the required investments, it is important to identify the key social dimensions that are relevant to WSS access. In general terms, it covers aspects such as coverage, affordability, service quality, equity, and customer satisfaction. However, at this stage, and considering the others as assumptions, affordability (of the required investments) will be the key issue.

Affordability, in this context, aims to guarantee that all individuals can access an adequate amount of water while paying a fair and reasonable price. This justifies providing special support (e.g., subsidies) to low-income households to meet their basic water needs (Pinto and Marques, 2016). This issue is particularly significant in developing countries characterized by wide income disparities and severe poverty challenges.

In this initial assessment of affordability, we evaluate how the average income of families corresponds to the potential increase in tariffs required for expanding investments and achieving universal access goals. To begin, we calculate the Tariff Review Index (TRI) based on the current average tariff and the required one (to allow reaching the universal access to WSS under the defined timeframe), which helps us determine the requirements to achieve financial-economic balance. This allows us to establish the average tariff required to achieve universalization. By using this information, we can calculate the disposable income commitment to WSS. The results of this calculation, specifically the percentage of income commitment, are then compared to the affordability thresholds set by the United Nations (UN). The UN recommends that the portion of disposable income allocated to WSS, for a standardized amount of water, should be below 5% (UN, 2011). Comparing the results to established affordability benchmarks helps us assess the financial burden on households (according to their income level) and determine if additional measures, such as subsidies, are needed to ensure affordable and equitable access to WSS.

Based on the findings, specific strategies, policies, or programs can be proposed to enhance affordability. These recommendations can inform future decision-making and guide the utility's efforts in improving its social impact.

3. Empirical analysis: State of Santa Catarina, Brazil

3.1. The Legal, Institutional, and Operational Context

Federal Law n.º 14,026/2020 established targets for providing 99% of the population with drinking water and 90% with sewage collection and treatment by 2033. However, this is an audacious goal for the State of Santa Catarina, which currently has 90% of water supply coverage and 25% of sewage network coverage (of which 94% are treated) (SNIS, 2020). This section is dedicated to presenting the legal and institutional context in the state of Santa Catarina for achieving these goals. The effective responsibility for implementing and promoting access to services lies with the municipality, the service holder, which can provide them directly or through delegation. Regarding regulators, their functions are established by Article 22 of Law No. 11,445/07, namely, creating standards and norms and ensuring compliance with the conditions and goals defined in contracts and WSS plans. In addition, they must define tariffs that balance the financial and economic sustainability of operators with reasonable tariffs. Specifically on the universalization of services, in accordance with Law No. 11,445/07, the service holder must prepare a municipal WSS plan (MWSSP), which should include investment plans and expansion of service coverage. If the municipality delegates the provision of services, the contracts must include these goals. In this context, the role of regulatory agencies is to require service providers (direct or delegated) to comply with the goals, investments and indicators set out in contracts or in the MWSSP.

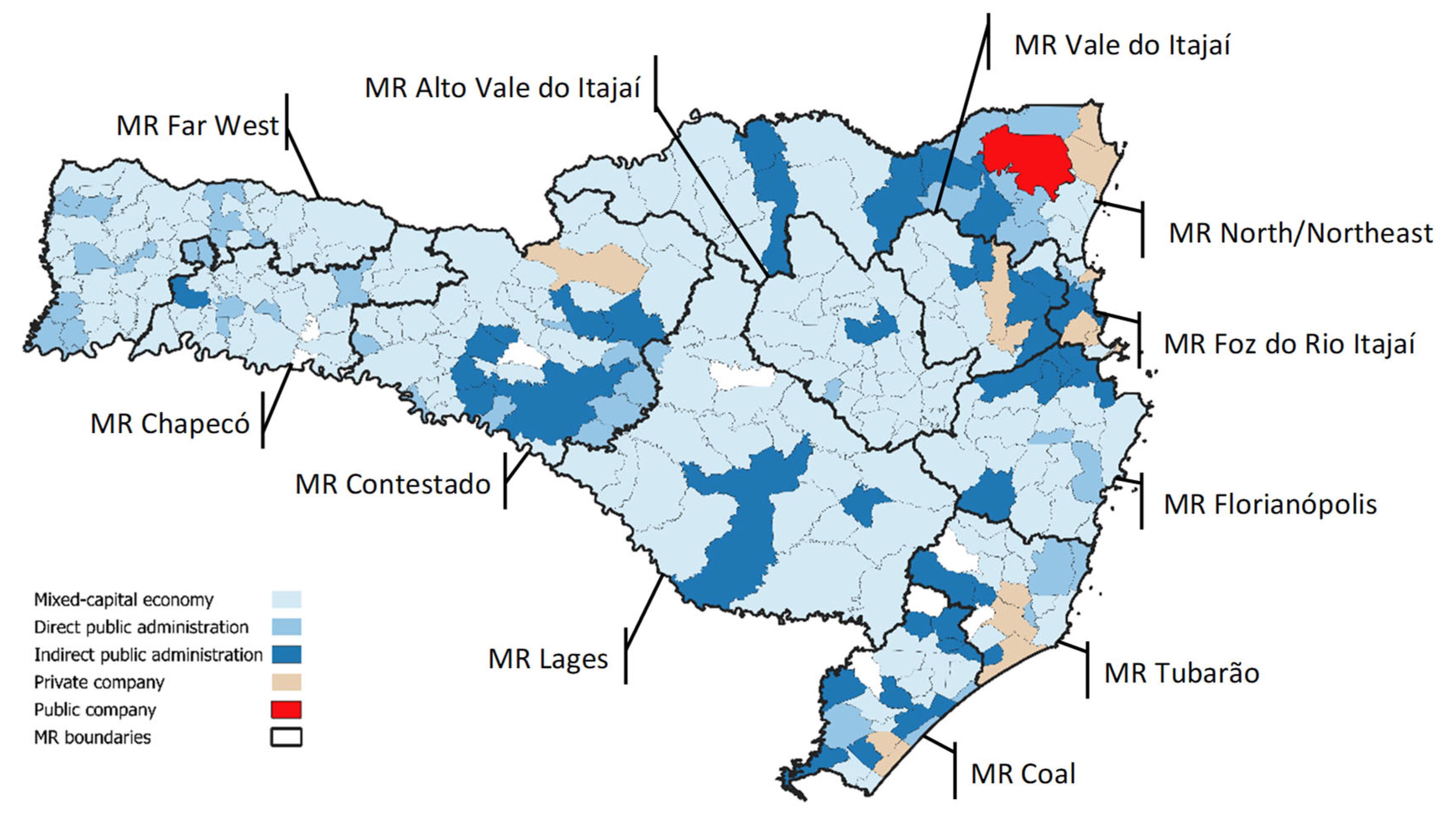

Regarding the legal status of service providers (

Figure 2), most (62.7%) of the 295 municipalities in the State of Santa Catarina are supplied by a mixed-capital company, Casan (Catarinense WSS Company). The second largest group of municipalities are delivered through direct public administration (18.01%) or indirect public administration (14.47%). And finally, those supplied by private companies (4.5%) or public companies (0.32%). However, there are changes in this proportion when looking at the actual population covered. Mixed-capital companies supply 43% of the population, direct public administration 10%, indirect public administration 27%, private companies 12%, and public companies’ cover 8%.

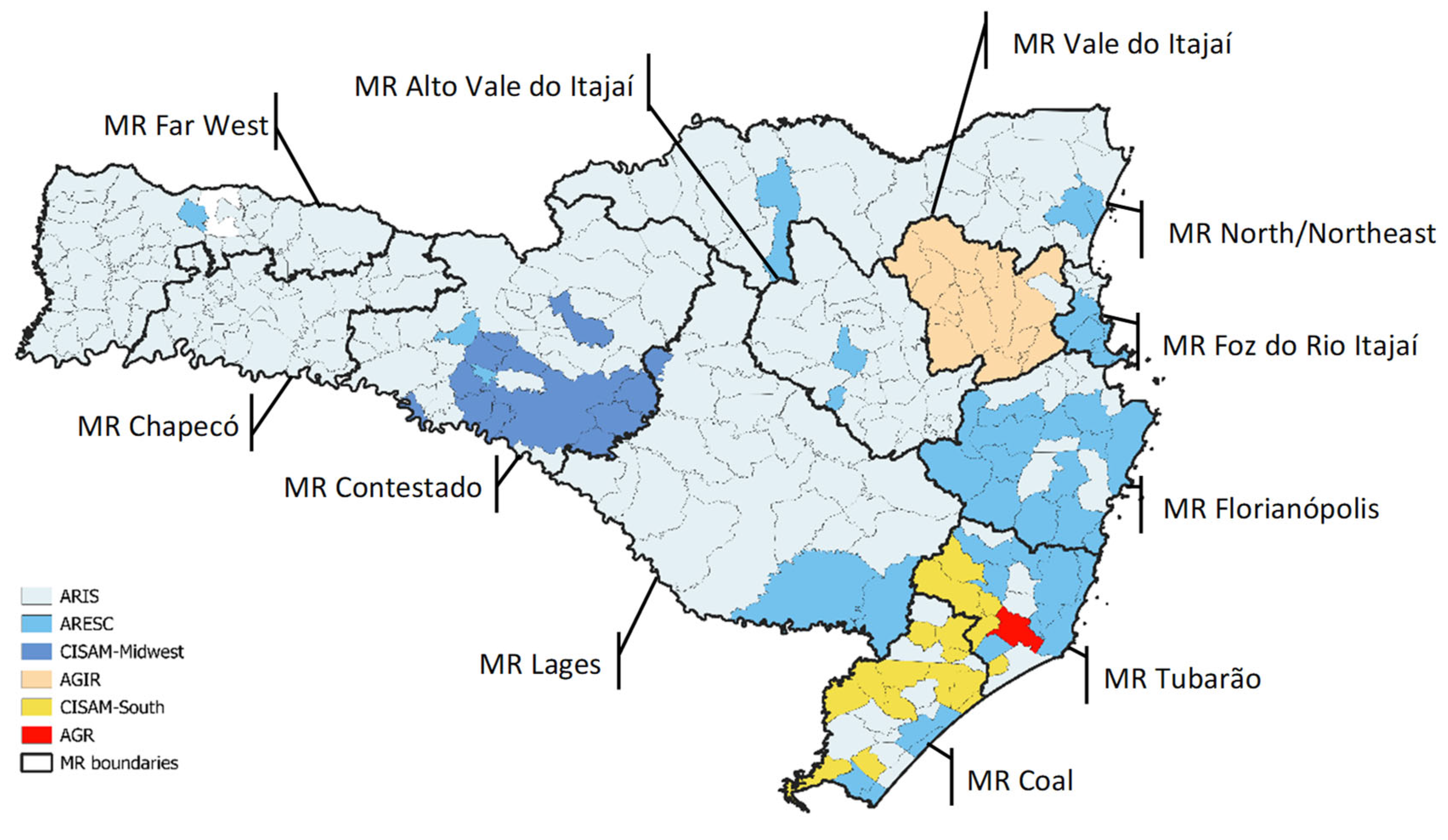

In Santa Catarina, 99% of the municipalities have a regulatory agency responsible for monitoring the water supply and sewage systems (

Figure 3). The state has six regulatory agencies: a) Agência Reguladora de Serviços Públicos de Santa Catarina – ARESC (State agency), which is responsible for 15% of the municipalities and 25% of the population; b) Agência Reguladora Intermunicipal de Saneamento – ARIS (intermunicipal consortium), with great capillarity throughout the state, serving 70% of the municipalities and 53% of the population; c) Agência Intermunicipal de Regulação do Médio Vale do Itajaí – AGIR (intermunicipal consortium), responsible for 5% of the municipalities and 11% of the population; d) Consórcio Intermunicipal de Saneamento Ambiental – CISAM (intermunicipal consortium), regulates the operators of 13 municipalities in the midwest region, which represents 3% of the population; and e) the Agência Reguladora de Saneamento de Tubarão – AGR (municipal agency), responsible for the regulation of Tubarão city’s utility.

A criticism of regulation in the State is that a share of the regulators does not effectively exercise all the functions delegated to them (their role is reduced to tariff definition/revision). One of the main factors is the lack of technical structure to monitor all contracts and MWSSP. Regarding the decision-making independence of these regulators, it is observed that there is a formal autonomy (de jure) guaranteed by the adopted public administrative models, which provide administrative and financial autonomy. However, in practice (de facto) there are significant concerns regarding political interference. The frequent changes in personnel and positions within the governing body, coupled with financial limitations, contribute to a sense of distrust.

Finally, a specificity of Santa Catarina is the attempt to promote regional WSS (Santa Catarina established the regionalization of WSS, State Decree No. 1,372/2021). The regional WSS units were divided by Metropolitan Region (MR), according to Complementary Law nº 495, 2010, and by Complementary Law No. 636, 2014. The 11 MRs have different characteristics related to their territories, population density and level of WSS coverage. Only two regions have more than one million inhabitants, the MR North/Northeast of Santa Catarina, and the MR Florianópolis. Nonetheless, to keep the analysis simpler and comparable, these metropolitan regions were used as territorial blueprints for the regional WSS utilities.

The population dynamics in urban areas demonstrate an average urban population of around 85%, with the highest concentration reaching 96% and the lowest at 58%. To further understand the scope of the challenge in achieving universal access, only “improved” WSS will be considered (as in Pinto et al., 2015), including full network and decentralized (e.g., septic tanks) systems. On average, the territory has a 90% coverage rate for water services (households supplied), with the highest index being 98% and the lowest at 73%. Regarding sanitary sewage services provided through networks, the average coverage stands at approximately 40%, with the best level at about 74% and the worst around 18%. For detailed information on each of the regional utilities, please see

Table 2, which provides comprehensive data on WSS coverage rates and population, emphasizing the proportion of urban residents.

3.2. Financial-Economic Viability of Regional Utilities

The evaluation of financial-economic viability of regional utilities, again for comparability purposes, will be done through the indicators proposed in Decree 10,710/2021 that sets a methodology to evaluate the financial-economic viability of utilities towards the universal access to WSS (particularly useful for Public-Private Partnerships, PPP). Thus, as defined in

Section 2.2, the indicators defined in

Table 3 will be calculated through the median values of data extracted from the balance sheets and statements of the last five financial years. The evaluation will then be made against the reference value of each indicator.

The cost assumptions, including the required investments to achieve the targets defined in

Section 3.1, will follow the estimations published by the Ministry of Cities in 2011, duly updated to present values through the National Construction Cost Index (INCC until Dec/19). Thus, it is possible to establish reference values to estimate the required investments to universalize WSS by 2033.

Table 2 presents the average values of investment to expand the coverage of services.

Since the values in

Table 4 depend on the Population, and the number of households, of each region in 2033 (target date), the values will be estimated considering the data available in SNIS (2020), e.g., WSS coverage data, and the population growth rate used by IBGE. For cases in which the population growth rate is equal to (or less than) zero, then a constant population was considered. Depending on the assumptions made regarding population growth projections and the estimated investment requirements for achieving universal access in all cities by 2033, cash flow projections were made for a 30-year time frame. In other words, using the available information from 2019, projections were made until 2051, and the net present value for each municipality was calculated using a discount rate of 10% per year. In a preliminary analysis of the current situation of each regional utility (by aggregating all respective local utilities), the available information allows to observe that only four, out of the eleven regional utilities, are in surplus over a five-year cycle (2015 to 2019), as highlighted in

Table 5.

The required investments, to universalize access to WSS, are then compiled in three phases for each regional utility (

Table 6). The project is divided into three phases: the first phase spans 5 years, the second phase lasts for 4 years, and the final phase covers a duration of 3 years. These phases are designed to demonstrate the financial resources that each utility must secure before the investment execution period begins.

For the investments estimated in

Table 6, and considering similar operational efficiencies and revenue streams (i.e., no increase in tariffs, direct subsidies, or others), the NPV of each regional utility, under a discount rate of 10%, is negative. Hence, without revising the initial conditions, there is no financial-economic balance within the utilities, and thus, the indicators in

Table 3 will be used as constraints (to be fulfilled) when assessing the required revenue increases.

3.3. The social Impact of Regional Utilities

The analysis undertaken to assess the financial and economic feasibility of each utility, used a “business-as-usual” approach (no tariff increases were considered). To achieve a financial-economic balance, the revenue requirement was used as an adjustment tool, employing a TRI and demanding compliance with the indicators highlighted in

Table 3. This index represents a revenue multiplier over the project horizon that ensures the NPV equals zero, while considering a discount rate of 10%. The aim was to identify the necessary revenue adjustments that would establish a balanced financial and economic outcome for each utility.

The results obtained are shown in

Table 7, which presents the TRI required to achieve a Financial-Economic balance. The results achieved allow to perceive significant tariff increase requirements for some regional utilities. Thus, it is important to assess whether that increase can be solely absorbed by the tariffs, or if additional sources of finance (

Figure 1) are required. To promote such an analysis, the statal minimum wage (for 2021: R

$ 1281) for two household non-dependents was used. The standardized amount of water to be included in the affordability measurements will be 10 m3 (2x for WSS), due to the usual tariff structures employed in Brazil which include a consumption (guaranteed volume) of 10m3 (Pinto et al., 2021).

4. Discussion and Policy Implications

The results achieved highlight a considerable need for investments to achieve universal access to WSS. Additionally, to face the negative financial-economic balance, brought upon a current fragile standing and the mentioned investments, there is a need to optimize operating costs to generate greater efficiency, and increase financing sources. Those funding requirements may be absorbed significantly by WSS tariffs, nonetheless, further sources such as soft financing and subsidies are required to keep affordability.

The achievement of these WSS coverage goals, as well as other water SDGs, require an enabling environment through context-suitable water governance and financing pathways to reach universal access to WSS. The case of Santa Catarina highlights a complex legal environment with disaggregated regulatory standards that may constrain the regionalization of WSS.

The need for restructuring the sector while allowing to promote scale efficiencies and gain access to improved human resources seems a promising endeavor, however, there is also a need consider transaction costs. In fact, among the many delivery models devised to cope with the financial hurdles of local governments, there may be a latent opportunism that may hinder their application. The PPPs are such an example, where the operational efficiency gains are balanced out by the political willingness to promote concession fees (to finance other political initiatives), which will have to be recovered through tariffs, as highlighted in (Vajdic et al., 2023).

The requirement for further financing sources and, perhaps, cross-subsidization, is also a challenging topic. Overall, as highlighted in

Figure 1, there is a requirement to improve opex, maintenance, and capex efficiencies throughout the whole financial strategic pathway to enable better financing conditions (e.g., relationship with lenders and other organizations). Regarding the different funding possibilities, in Brazil and certainly in most developing economies, there is a high risk related with exchange rate exposure on external loans and financing as they hold highly fluctuating currencies. During the renowned scarcity event in São Paulo (Brazil) in 2014-2016, the reliance on external finance escalated the problem (Pinto et al. 2021). Cross-subsidization may also be a challenging topic, as depending on who subsidizes who, there may be reduced business incentives to water intensive industries (when industry subsidizes domestic customers), or there may be a particular case of “double taxation” (when domestic customers subsidize other domestic customers). Some authors highlight that it may not be the best or even a suitable way to do it (Barraqué, 2011).

Lastly, there is the case of informal settlements. Universalizing access to WSS in informal settlements presents significant challenges due to the unique characteristics of these areas. Informal settlements, often characterized by their unplanned nature, lack of basic infrastructure, and absence of legal recognition, which casts out these local communities from official data. Thus, assessing the size of the problem and estimating the costs of developing WSS infrastructure in informal settlements pose significant challenges. Often, informal settlements are located in hazardous zones, such as flood-prone areas or steep slopes, making it essential to consider the relocation of those households or develop temporary solutions. Overall, there is a requirement to mitigate risks when designing and implementing WSS solutions. To address these challenges, urban planning, regularization efforts, and local community engagement are crucial. Legalizing informal settlements and providing secure land tenure can facilitate the integration of these areas into the formal urban fabric, enabling targeted investments in infrastructure, including WSS. Engaging local communities in the decision-making process ensures that solutions are tailored to their specific needs and priorities, fostering a sense of ownership and long-term sustainability. Indeed, achieving universal access to WSS in informal settlements requires a comprehensive and multi-dimensional approach that addresses legal, financial, technical, and social complexities.

5. Concluding Remarks

Achieving universal access to WSS in developing countries is an undertaking that requires a favorable and coherent legal, political, and institutional environment, as well as a clear and strategic financial pathway. It is evident that territories facing local disparities, marginalized communities, economic inequalities, and disaggregated governance structures encounter greater challenges in this regard. Therefore, regionalizing WSS services becomes crucial to improve and promote various aspects. Regionalization offers the potential for economies of scale, allowing for more efficient use of resources and cost savings. It facilitates the sharing of expertise and resources among different areas, promoting collaboration and knowledge exchange. Additionally, regionalization strengthens institutional capacity by establishing or reinforcing regional governance structures, enabling better coordination and decision-making. It also allows for risk diversification, ensuring service continuity in the face of shocks or crises. Furthermore, regionalization enhances policy coordination, enabling alignment between regional development strategies, service delivery plans, and national development goals. It fosters integrated and sustainable approaches to WSS. Additionally, it provides opportunities for stakeholder engagement and participation, involving local communities and civil society.

The cornerstone of regionalization will be ensuring the financial-economic viability of regional utilities, considering the social impacts in terms of affordability. This means striking a balance between cost-effectiveness and the ability of communities to afford the services.

Using the State of Santa Catarina as a case study, an assessment was conducted to understand the present condition of both individual municipalities and their aggregated regional utilities. The analysis revealed that only four regional utilities generate revenue exceeding their costs, but this revenue is insufficient to meet the investment requirements. This indicates the necessity to review the design parameters to address this shortfall. For regions where utilities do not demonstrate financial and economic viability in terms of customers' ability to pay, technical and financial support from federal level, the States and/or Municipalities will be required to ensure commitment to universal access goal, i.e., introducing additional sources of finance (

Figure 1).

The results achieved indicate that each regional utility has the potential to achieve universal access to WSS by adjusting the tariff structures, and in particular cases, additional finance adjustments. These adjustments must be made in a way that ensures affordability for families, without surpassing their ability to pay for WSS.

The text continues here.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.N., D.N. and F.S.P.; methodology, W.N., D.N. and F.S.P; investigation, W.N., D.N., F.S.P and T.C.; writing—original draft preparation, W.N., D.N., F.S.P and T.C.; writing—review and editing, F.S.P.; supervision, F.S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

F.S.P. and D.N. are grateful for the Foundation for Science and Technology’s support through funding 2022.13852.BD from the research unit CERIS.

Acknowledgments

Any errors and omissions are the responsibility of the authors. The usual disclaimer applies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Akhmouch, A. (2014). Water Governance in OECD Countries: A Multi-Level Approach. The “water crisis” is largely a governance crisis. OECD Water. (pp. 1-8). London, IWA Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Akhmouch, A.; Romano, O.; Gammeltoft, P. (2017). Governance of Drinking WSS Infrastructure in Brazil. p. 61.

- Barraqué, B. (2011). Is Individual Metering Socially Sustainable? The Case of Multifamily Housing in France. Water Alternatives, 4(2).

- Bolognesi, T., Pinto, F. S., & Farrelly, M. (Eds.). (2022). Routledge Handbook of Urban Water Governance. Taylor & Francis.

- Boukhari, S., Pinto, F. S., Abida, H., Djebbar, Y., & de Miras, C. (2020). Economic analysis of drinking water services, case of the city of Souk-Ahras (Algeria). Water Practice and Technology, 15(1), 10-18. [CrossRef]

- Brasil (2016). Altera o Ato das Disposições Constitucionais Transitórias, para instituir o Novo Regime Fiscal, e dá outras providências. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/ constituicao/ emendas/emc/emc95.htm.

- Brigham, E. F.; Ehrhardt, M. C. (2012). Administração financeira: teoria e prática. Cengage Learning, São Paulo. p. 328.

- Cetrulo, T.B.; Marques, R.C.; Malheiros, T.F. (2019). An analytical review of the efficiency of water and sanitation utilities in developing countries. Water Research 161, 372-380. [CrossRef]

- Cetrulo, T.B.; Marques, T.B.; Malheiros, T.F.; Cetrulo, N.M (2020a). Monitoring inequality in water access: Challenges for the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Science of the Total Environment, 727, 138746. [CrossRef]

- Cetrulo, T.B.; Ferreira, F.C; Marques, T.B.; Malheiros, T.F. (2020b). Water utilities performance analysis in developing countries: On an adequate model for universal access. Journal of Environmental Management, 268, 110662.Damodaran, A. (2004). Finanças Corporativas: Teoria e Prática. São Paulo: Bookman Companhia. [CrossRef]

- Elleuch, M. A., Hassena, A. B., Abdelhedi, M., & Pinto, F. S. (2021). Real-time prediction of COVID-19 patients health situations using Artificial Neural Networks and Fuzzy Interval Mathematical modeling. Applied soft computing, 110, 107643. [CrossRef]

- ExAnte (2018). Benefícios econômicos e sociais da expansão do saneamento no Brasil. Report. Instituto Trata Brasil.

- 1WSP (2020). Publications & Knowledge. Global Water Security & Sanitation Partinership. Washington: The World Bank Group. https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/global-water-security-sanitation-partnership/publications.

- Hutton, G.; Varughese, M. (2021). the Costs of meeting the 2030 Sustainable Development Goal targets on Drinking Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Summary report.

- Jenkins, G., 1978. Inflation and Cost-Benefit Analysis. Development Discussion Papers. JDI Executive Programs.

- Kolker, J. E., Kingdom, B., Trémolet, S., Winpenny, J., Cardone, R. (2016). Financing Options for the 2030 Water Agenda. [s.l.] World Bank, Washington, DC. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/25495.

- KPMG, ABCON (2020). Quanto custa universalizar o saneamento no Brasil? São Paulo.

- Lieberherr, E., Hüesker, F., & Pakizer, K. (2022). Rethinking urban water governance and infrastructure in Europe: Challenges and opportunities of regionalization and organizational autonomy. Routledge Handbook of Urban Water Governance, 272-283. [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, S.; Lührmann, A.; Mechkova, V. (2017). From de-jure to de-facto: Mapping dimensions and sequences of accountability. Background Paper for the World Development Report 2017. http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/585311486396458329/WDR17-BP-Accountability-paper.pdf.

- Machete, I., & Marques, R. (2021). Financing the WSS sectors: a hybrid literature review. Infrastructures. 6 (1). 1-9.

- Manghee, S., & Berg, C. V. D. (2012). Public Expenditure Review from the Perspective of the WSS Sector - GUIDANCE NOTE. June. Washington D.C.: World Bank.

- Marques, R. C., Pinto, F. S., & Miranda, J. (2016). Redrafting water governance: guiding the way to improve the status quo. Utilities Policy, 43, 1-3. [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, E. (2022). Policy coherence versus regulatory governance. Electricity reforms in Algeria and Morocco. Regulation & Governance, in press. [CrossRef]

- MDR (2019). Plano Nacional de Saneamento Básico. Brasília: Secretaria Nacional de Saneamento. https://antigo.mdr.gov.br/images/stories/ArquivosSDRU/ArquivosPDF/ Versao_Conselhos_Resolu%C3%A7%C3%A3o_Alta_-_Capa_Atualizada.pdf.

- Mitlin, D., & Walnycki, A. (2020). Informality as experimentation: water utilities’ strategies for cost recovery and their consequences for universal access. In: The Journal of Development Studies. 56. pp. 259–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2019.1577383. [CrossRef]

- Mumssen, Y., Saltiel, G., Kingdom, B. (2018). Aligning Institutions and Incentives for Sustainable Water Supply and Sanitation Services. Aligning Institutions Incent. Sustain. Water Supply Sanit. Serv.

- Nagpal, T., Malik, A., Eldridge, M., Kim, Y., & Hauenstein, C. (2018). Mobilizing Additional Funds for Pro-Poor Water Services. School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University. September. Washington D.C. https://www.oecd.org/water/Background-Document-OECD-GIZ-Conference-Urban-Institute-GIZ-Innovative-Financing-Mechanisms-final.pdf.

- Narzetti, D.A., Marques, R.C (2021a). Access to water and sanitation services in Brazilian vulnerable areas: The role of regulation and recent institutional reform. Water 13. [CrossRef]

- Narzetti, D.A., Marques, R.C (2021b). Isomorphic mimicry and the effectiveness of water-sector reform in Brazil. Utilities Policy 70, 101217. [CrossRef]

- Novaes, C., Silva Pinto, F., & Marques, R. C. (2022). Aedes Aegypti—Insights on the Impact of Water Services. Geohealth, 6(11), e2022GH000653. [CrossRef]

- OECD (2019). Making Blended Finance Work for WSS: Unlocking Commercial Finance for SD G6. OECD Studies on Water. Paris: OECD.

- Ostrom, E (2010). Beyond markets and states: polycentric governance of com- plex economic systems. Am. Econ. Rev. 100 (3).

- Perard, E (2018). Financial and economic aspects of the sanitation challenge: A practitioner approach. Utilities Policy, v. 52, n. March, p. 22–26. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, F. S., de Carvalho, B., & Marques, R. C. (2021). Adapting water tariffs to climate change: linking resource availability, costs, demand, and tariff design flexibility. Journal of Cleaner Production, 290, 125803. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, F. S., Figueira, J. R., & Marques, R. C. (2015). A multi-objective approach with soft constraints for water supply and wastewater coverage improvements. European Journal of Operational Research, 246(2), 609-618. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, F. S., & Marques, R. C. (2016). Tariff suitability framework for water supply services: establishing a regulatory tool linking multiple stakeholders’ objectives. Water Resources Management, 30, 2037-2053. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, F. S., Tchadie, A. M., Neto, S., & Khan, S. (2018). Contributing to water security through water tariffs: some guidelines for implementation mechanisms. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 8(4), 730-739. [CrossRef]

- EMADS-MG (2021). Nota Técnica: Metodologia de Construção das Unidades Regionais de Saneamento Básico Estado de Minas Gerais. Secretaria de Meio Ambiente e Desenvolvimento Sustentável, Governo do Estado de Minas Gerais. Belo Horizonte, Brasil.

- UN (2011). The Human Right to WSS Media brief.

- UN (2020). WSS – United Nations Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/water-and-sanitation/.

- UNDP (2022). Atlas Brazil. http://www.atlasbrasil.org.br/ranking.

- Vajdic, N., Mladenovic, G., & Queiroz, C. (2023). Enhancing the feasibility of airport PPP projects with hybrid funding. Transportation Research Procedia, 69, 600-607. [CrossRef]

- WORLD BANK; IFC; ASSOCIADOS, GO. (2013). Water utilities performance-based contracting manual in Brazil-WAUPBN. International Finance Corporation and World Bank Group.

- Yepes, G., & Dianderas, A. (1996). Water & wastewater utilities: indicators 2nd edition. Water and Sanitation Division, The World Bank.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).