Submitted:

05 June 2023

Posted:

06 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Study Overview

1.2. Perceptual Assessment and Urban image

1.3. Logistic Regression Model

2. Methods

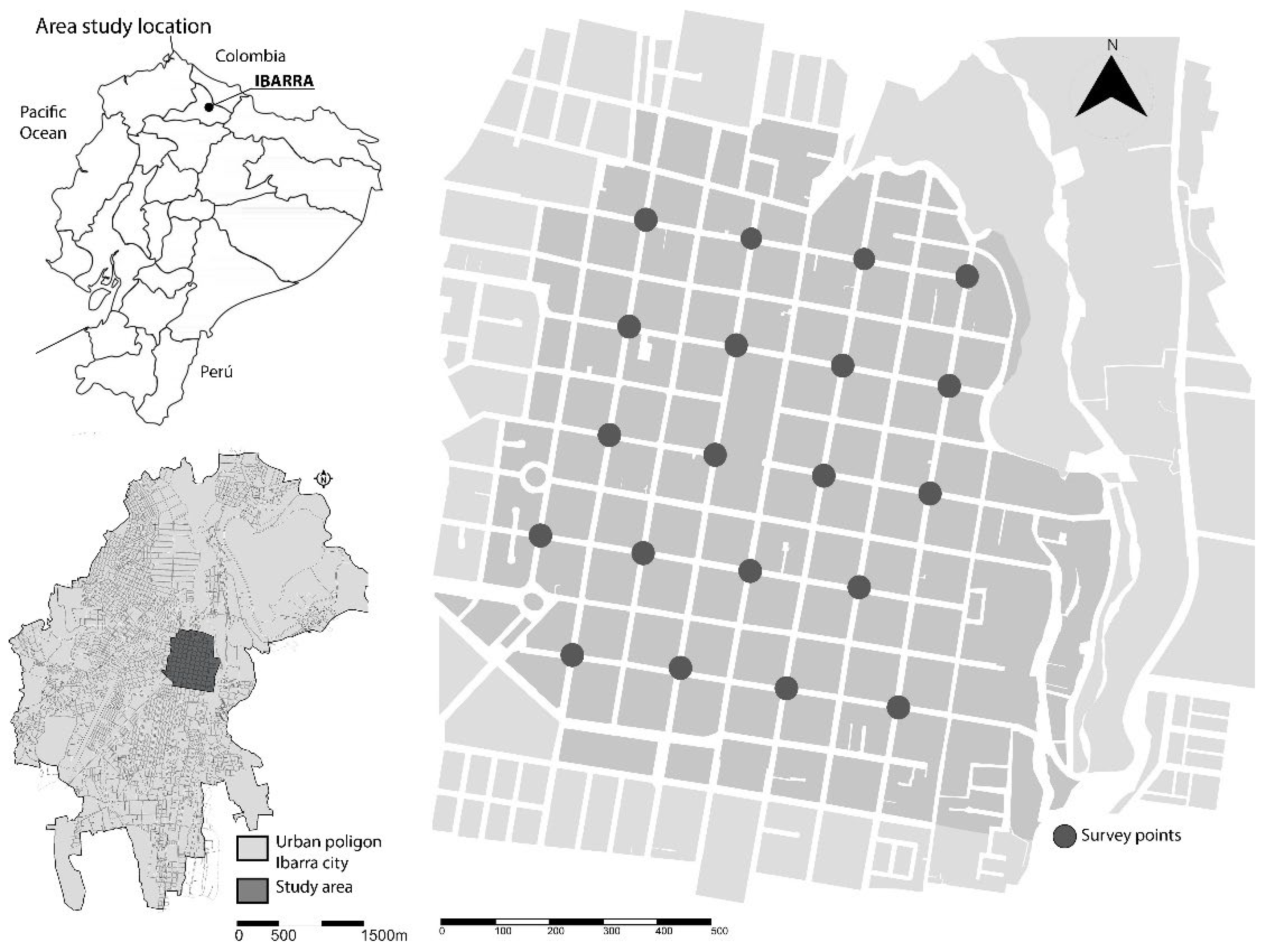

2.1. Spatial Scope of the Historic Landscape of Ibarra

2.2. The Survey

- Likes to: What are the three places, objects, buildings, or roads that you like the most in the historic downtown of the city of Ibarra?

- Dislikes to: What are the three places, objects, buildings, or roads that you most dislike in the historic downtown of the city of Ibarra?

2.3. Quantitative Data Analysis

2.4. Planimetry

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis of Liking and Disliking

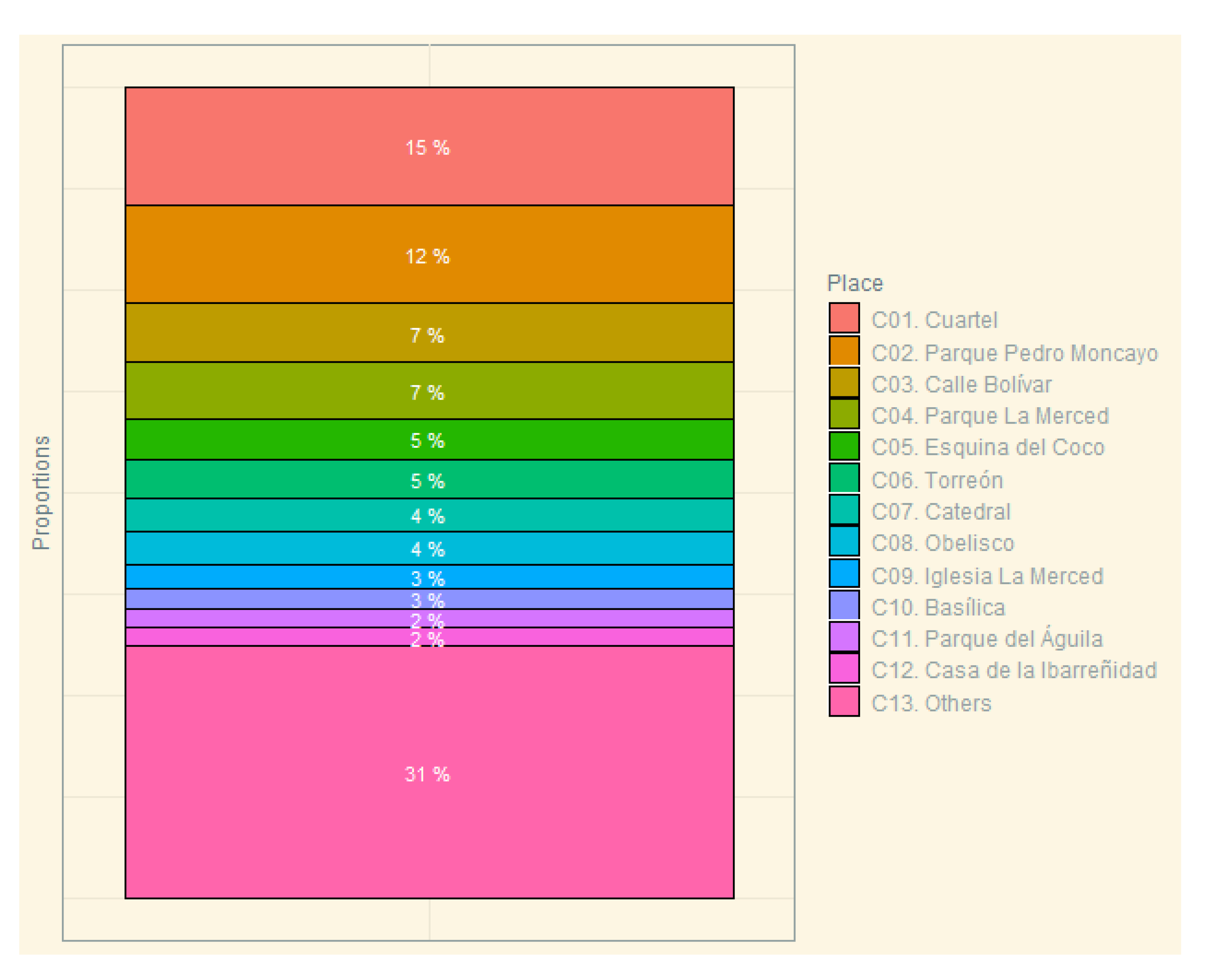

3.1.1. Description of Liking

- The foundational nucleus in the center of the map, formed by the elements close to the Pedro Moncayo and La Merced Parks. In these places the natural elements are remembered as the reason for liked.

- To the south, is the “Esquina del Coco”, Águila square, joined to Bolívar Street.

- To the southwest, the Obelisk near train station.

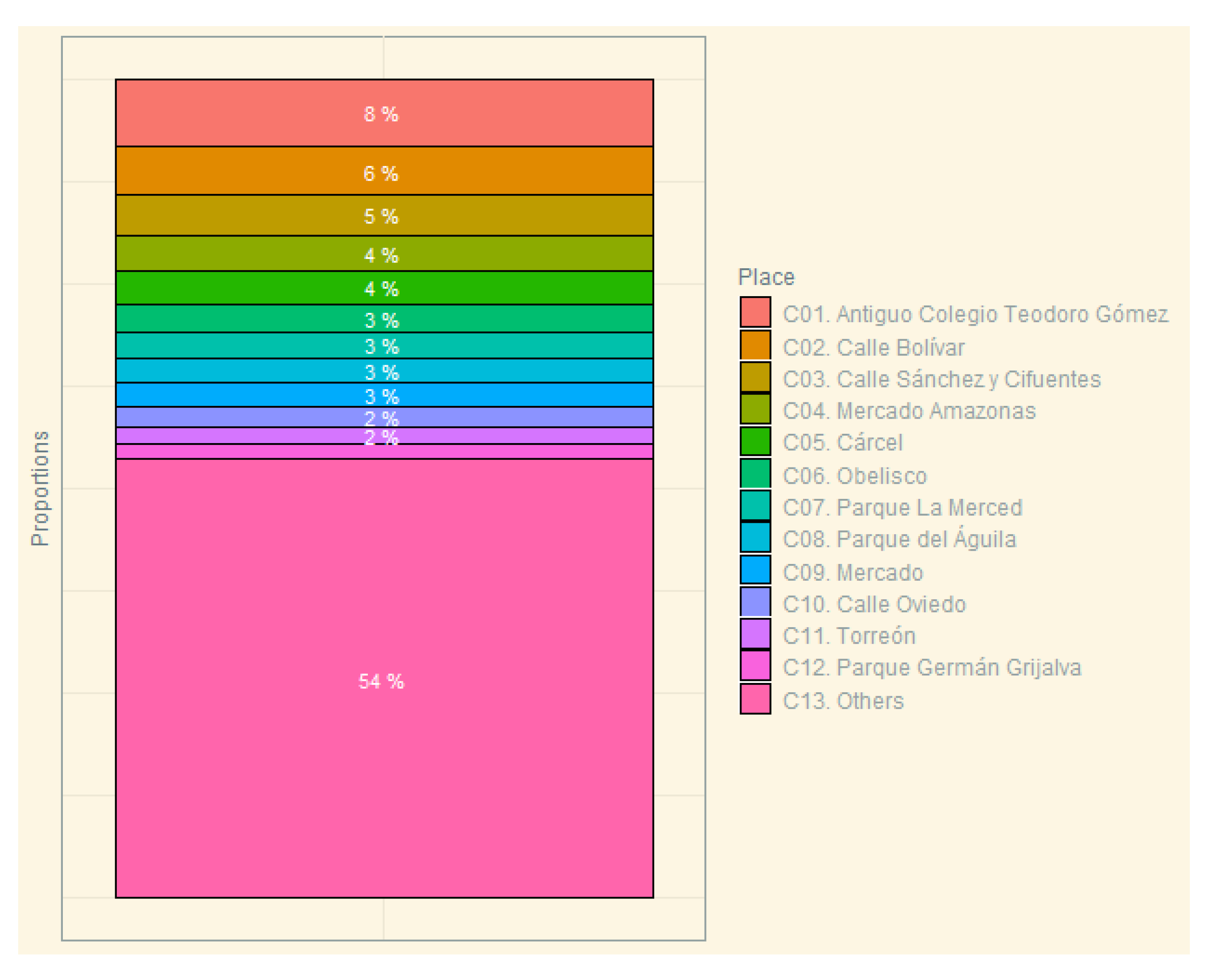

3.1.2. Description of Disliking

- The central nucleus (the Teodoro Gómez School and the Torreón, the Municipality and the La Merced and Moncayo Parks stand out).

- To the southwest, the Obelisk and the Amazon Market.

- To the northeast, the jail (“La Cárcel”), as a third sequence linked to the edge of the slope of the Tahuando River, a predominantly residential sector.

- To the northwest, the Santo Domingo market linked to Boyacá Park to the north.

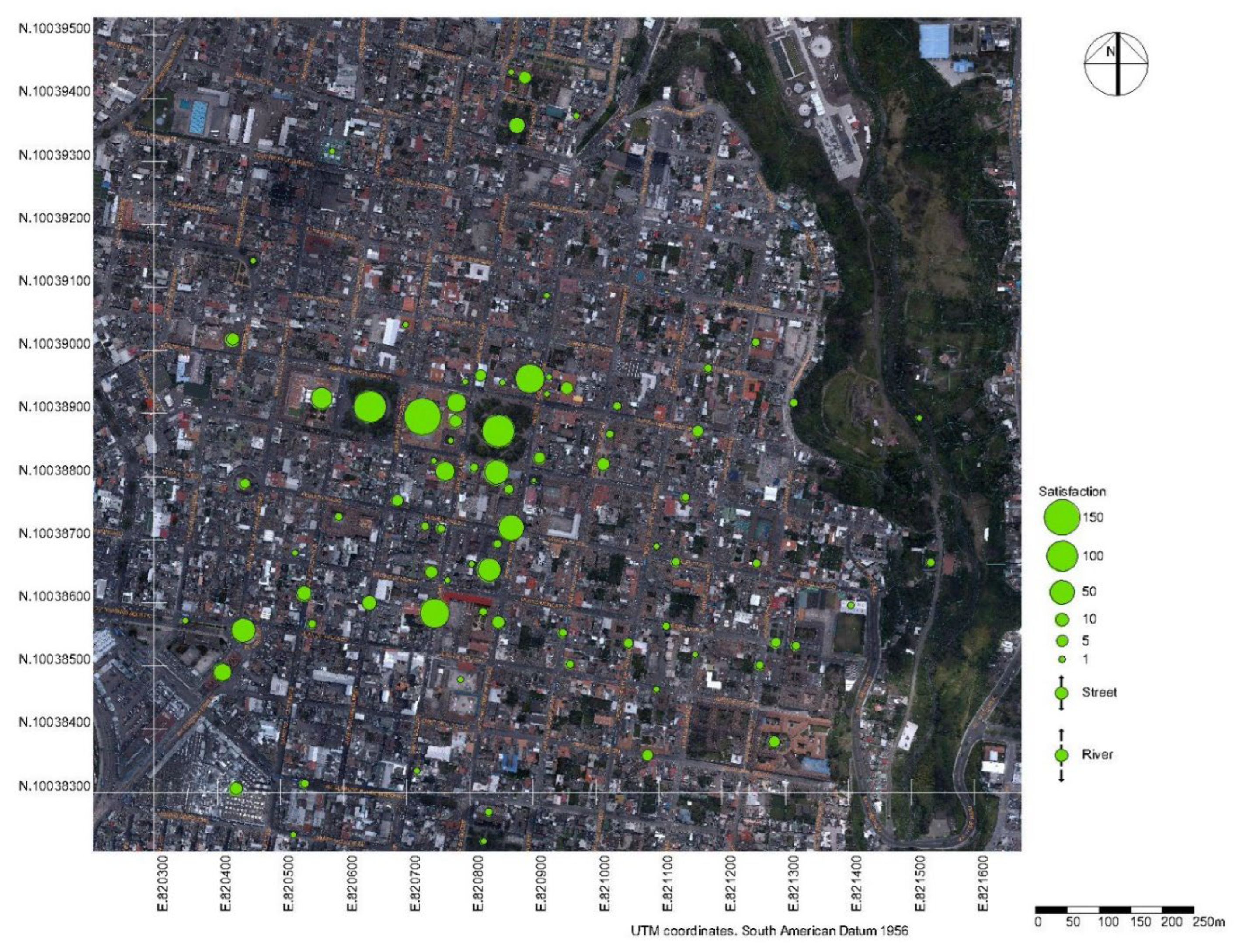

3.2. Net Liking Description

- The Cuartel, Pedro Moncayo Park, La Merced Park, the Cathedral stand out for the pleasure they represent. For the church of La Merced and the house of Ibarreñidad, liking diminishes. Of this central nucleus, the Old Teodoro Gómez School stands out due to felt disliking. Towards the south, the “Esquina del Coco”, shows more liking than disliking.

- “Santo Domingo” market to the northwest, shows greater disliking.

- The jail (“La Cárcel”) to the northeast shows greater disliking.

- The train station and the Obelisk to the southwest, complete the access to the historic downtown as places that like and dislike, respectively.

3.3. Explanatory Analysis of Liking

3.4. Explanatory Analysis of Disliking

4. Discussion

- Gender in 4 opportunities,

- Age 5 times,

- Level in 2 opportunities.

- Frequency in 3 opportunities.

- Gender in 7 opportunities,

- Age 8 times,

- Level in 2 opportunities.

- Frequency in 11 opportunities.

- Mitigate the public's perception of dislike for the historic downtown.

- Strengthen the perception of the public's liking for said sector.

5. Conclusions

References

- Agresti, A. (2015). Foundations of Linear and Generalized Linear Models. (J. W. & Sons. (Ed.)).

- Aguilar, A. (2006). Algunas consideraciones teóricas en torno al paisaje como ámbito de intervención institucional. Redalyc, 79, 5–20.

- Briceño Ávila, M., Sánchez Villarreal, A., Tamayo Revilla, J., Izquierdo Guerrero, H., Ponsot Balaguer, E., Ulloa Quintero, R., & Camacho Peña, L. (2021). Capas Historicas del Paisaje Urbano de Ibarra. Revista Geográfica Venezolana, 62 (1), 256–271.

- Chenoweth, R. E., & Gobster, P. H. (1990). The Nature and Ecology of Aesthetic Experiences in the Landscape. Landscape Journal, 9(1). [CrossRef]

- Galindo, M. P., & Corraliza, J. A. (2012). Estética ambiental y bienestar psicológico: algunas relaciones existentes entre los juicios de preferencia por paisajes urbanos y otras respuestas afectivas relevantes. Apuntes De Psicología, 30(1–3).

- Gatersleben, B., Wyles, K. J., Myers, A., & Opitz, B. (2020). Why are places so special? Uncovering how our brain reacts to meaningful places. Landscape and Urban Planning, 197. [CrossRef]

- Hilbe, J. M. (2009). Logistic Regression Models. (C. & Hall. (Ed.); 1st. editi).

- Hussein, F., Stephens, J., & Tiwari, R. (2020). Cultural memories and sense of place in historic urban landscapes: The case of Masrah Al Salam, the demolished theatre context in Alexandria, Egypt. Land, 9(8). [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS. (2014). The Florence Declaration on Heritage and Landscape as Human Values. 18th General Assembly, 7.

- Instituto Nacional de Patrimonio Cultural, Ecuador. (n.d.). https://www.patrimoniocultural.gob.ec/.

- Kaplan, S. y Kaplan, R. (1982). Cognition and Environment. Functioning in an uncertain world (P. Publishers (Ed.)).

- Kent, J. L., Ma, L., & Mulley, C. (2017). The objective and perceived built environment: What matters for happiness? Cities and Health, 1(1). [CrossRef]

- Luo, T., Xu, M., Liu, J., & Zhang, J. (2019). Measuring and Understanding Public Perception of Preference for Ordinary Landscape in the Chinese Context: Case Study from Wuhan. Journal of Urban Planning and Development, 145(1). [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K. (2015). La imagen de la ciudad. (Tercera ed). Gistavo Gili.

- Marshall, S. (2012). Science, pseudo-science and urban design. Urban Design International, 17(4), 257–271. [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, R. H., & Kaplan, R. (2008). People needs in the urban landscape: Analysis of Landscape And Urban Planning contributions. In Landscape and Urban Planning (Vol. 84, Issue 1). [CrossRef]

- MCCullagh, P.; Nelder, J. (1989). Generalized Linear Models. (C. & Hall. (Ed.); 2d. editio).

- McHarg, I. (2000). Proyectar con la naturaleza. (G. Gili (Ed.)).

- Méndez, M. L., Otero, G., Link, F., López Morales, E., & Gayo, M. (2021). Neighbourhood cohesion as a form of privilege. Urban Studies, 58(8), 1691–1711. [CrossRef]

- Mondschein, A., Blumenberg, E., & Taylor, B. D. (2006). Cognitive mapping, travel behavior, and access to opportunity. Transportation Research Record, 1985. [CrossRef]

- Nassauer, J. I., Webster, N. J., Sampson, N., & Li, J. (2021). Care and safety in neighborhood preferences for vacant lot greenspace in legacy cities. Landscape and Urban Planning, 214. [CrossRef]

- Ode, A., Fry, G., Tveit, M. S., Messager, P., & Miller, D. (2009). Indicators of perceived naturalness as drivers of landscape preference. Journal of Environmental Management, 90(1), 375–383. [CrossRef]

- Ode, Å. K., & Fry, G. L. A. (2002). Visual aspects in urban woodland management. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 1(1), 15–24. [CrossRef]

- Ponsot, Briceño, Izquierdo, Rondón, Sánchez, Tamayo, Ulloa, C. (2019). Imagen urbana del centro histórico de Ibarra. Reporte estadístico. (P. Coeditado PUCE (Ed.); 1ra. Edici).

- R Core Team. (2018). “R: A language and environment for statistical computing.” R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.

- Russell, J. A. (1980). A circumplex model of emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(6), 1161–1178.

- Russell, J. A. (2003). Core Affect and the Psychological Construction of Emotion. Psychological Review, 110(1), 145–172. [CrossRef]

- Russell, J. A., & Pratt, G. (1980). A description of the affective quality attributed to environments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38(2), 311–322. [CrossRef]

- Saltos, R. y Torres, F. (1999). Inventario arquitectónico y urbano de Ibarra y Caranqui. Tomos I, II, III, IV.

- Scheaffer, Richard L.; Mendenhall III, William; Lyman Ott, R.; Gerow, K. (2012). Elementary Survey Sampling. (C. L. Brooks/Cole (Ed.); 7th. editi).

- Sotoudeh, H., & Abdullah, W. M. Z. W. (2013). Evaluation of fitness of design in urban historical context: From the perspectives of residents. Frontiers of Architectural Research, 2(1). [CrossRef]

- Verdaguer, C. (2005). I FORO URBANO DE PAISAJE VITORIA-GASTEIZ 2005 Periferias : hacia dentro , hacia fuera ”. 1–11.

- von Schönfeld, K. C., Bertolini, L., Jalaladdini, S., Oktay, D., Gavrilidis, A. A., Ciocănea, C. M., Niţă, M. R., Onose, D. A., Năstase, I. I., Santos, H., Valença, P., Fernandes, E. O., Zhang, Y., Wei, T., Talen, E., Wheeler, S. M., Anselin, L., Said, S., Samadi, Z., … Werthmann, C. (2018). Urban Streets between Public Space and Mobility. Landscape and Urban Planning, 177(August 2017), 221–229. [CrossRef]

| Place | Mentions | Gender | Age | Level | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bolívar Street | 83 | 0.7416429 | 0.0292015 | 0.4441903 | 0.8351808 |

| La Merced Park | 81 | 0.8628450 | 0.4893984 | 0.0650289 | 0.9683314 |

| “Coco” corner | 56 | 0.0657850 | 0.1754848 | 0.1495044 | 0.1942257 |

| Águila park | 27 | 0.1416262 | 0.0383923 | 0.9390357 | 0.7279376 |

| House of Ibarreñidad | 25 | 0.0230201 | 0.7701085 | 0.2145067 | 0.3100739 |

| Municipality | 21 | 0.0009448 | 0.0927905 | 0.9212920 | 0.0688232 |

| Parks | 15 | 0.8958459 | 0.6263178 | 0.9172531 | 0.0243222 |

| Amazonas market | 9 | 0.3999454 | 0.1323162 | 0.0051522 | 0.4088890 |

| Gubernation | 8 | 0.0698998 | 0.8883960 | 0.9436454 | 0.3407143 |

| House of Culture | 7 | 0.9483484 | 0.0118852 | 0.9738643 | 0.6938977 |

| San Agustin Park | 5 | 0.3028039 | 0.3634427 | 0.9376864 | 0.0468278 |

| Santo Domingo Park | 5 | 0.4086241 | 0.0238938 | 0.5796059 | 0.7864686 |

| Place | Mentions | Gender | Age | Level | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old School Teodoro Gómez | 77 | 0.8866097 | 0.0024428 | 0.7303522 | 0.0072908 |

| Bolívar street | 55 | 0.0785330 | 0.1869312 | 0.3509629 | 0.0855646 |

| Oviedo street | 23 | 0.5743604 | 0.7984397 | 0.0480603 | 0.2813004 |

| Torreón | 19 | 0.0193507 | 0.0075865 | 0.2009983 | 0.0699608 |

| Sucre street | 15 | 0.0676320 | 0.6716970 | 0.9360196 | 0.3390099 |

| Streets | 14 | 0.0253150 | 0.3562462 | 0.4202115 | 0.2437234 |

| Águila corner | 14 | 0.0922955 | 0.3790603 | 0.5076561 | 0.7452506 |

| Colón street | 10 | 0.4276690 | 0.7525072 | 0.5390799 | 0.0418257 |

| La Merced | 9 | 0.8858647 | 0.4555600 | 0.7361766 | 0.0536881 |

| Parks | 9 | 0.8858647 | 0.0775044 | 0.1658753 | 0.7805286 |

| CDP | 9 | 0.5883539 | 0.9530894 | 0.0283807 | 0.2666959 |

| Pérez Guerrero avenue | 8 | 0.3107308 | 0.0409240 | 0.9105563 | 0.5584130 |

| Rocafuerte street | 7 | 0.1095277 | 0.0453028 | 0.1493349 | 0.0853283 |

| García Moreno Street | 7 | 0.1151545 | 0.0946186 | 0.3550165 | 0.2340110 |

| Downtown | 7 | 0.1151545 | 0.1869640 | 0.9520019 | 0.0662332 |

| Maldonado street | 7 | 0.4573733 | 0.0907178 | 0.6540553 | 0.2565751 |

| Cuartel | 6 | 0.0366411 | 0.7813976 | 0.1682423 | 0.0209531 |

| Houses | 5 | 0.4198078 | 0.3989958 | 0.8965343 | 0.0310402 |

| Sidewalks | 5 | 0.0031974 | 0.9016575 | 0.1029840 | 0.4694090 |

| Buildings | 4 | 0.7495943 | 0.7064859 | 0.1802656 | 0.0391396 |

| Pedro Moncayo street | 4 | 0.4744064 | 0.0720332 | 0.9868813 | 0.9342418 |

| Heritage houses | 4 | 0.1804498 | 0.1468933 | 0.9488239 | 0.0370756 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).