1. Introduction

It is well established that cardiac resynchronisation therapy (CRT) implantation in patients with heart failure reduces overall mortality and improves quality of life [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

International guidelines have been very clear when it comes to patient selection for de novo implant in recipients who meet the criteria; however, the evidence is less clear when it comes to upgrading an existing pacemaker implanted for bradyarrhythmia or an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) to CRT. This leads to a hypothesis of whether we are under-treating a population that would otherwise benefit from CRT [

7].

The 2013 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronisation gives a class IB indication to upgrading an existent pacemaker or an ICD to CRT in patients with heart failure, New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III, high burden right ventricular pacing and left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (EF) <35% despite optimal medical treatment [

8]. The 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronisation, however, give a class IIa level of evidence B indication for the same group. These give a class I level of evidence for an indication for CRT with chronic right ventricular (RV) pacing for patients with an EF <40% regardless of NYHA class [

9].

The BUDAPEST-CRT trial is the only randomised clinical trial to date in upgrade patient groups [

10]. The only other trials are small study group retrospective studies that have been carried out to identify whether upgrading to a CRT from a conventional pacemaker or an ICD is indeed of clinical benefit.

A study by Fang et al. involving 93 patients, revealed that half of the patients would develop heart failure (HF) and impaired systolic function due to high burden right ventricular pacing [

11]. The BLOCK-HF trial demonstrated that in patients with atrioventricular block and systolic dysfunction, biventricular (BiV) pacing not only reduces the risk of mortality/morbidity, but also leads to better clinical outcomes, including improved quality of life and HF status, compared to RV pacing [

12]. Several other studies have demonstrated that in patients with HF and chronic right ventricular pacing, upgrade to CRT was similar to de novo CRT implant in the long term in terms of mortality, reverse LV remodelling and symptomatic improvement [

6,

13,

14,

15,

16].

As upgrading to CRT covers both conventional pacemakers and ICDs, there have only been a few small studies comparing the two. Studies so far are encouraging when it comes to upgrading a conventional pacemaker to a CRT; however, this is not the same with the ICD group. In a study by Vamos et al., it was demonstrated that both clinical response and long-term survival were less favourable in patients undergoing cardiac resynchronisation therapy – Defibrillator (CRT-D) upgrade compared to de novo implantations [

17,

18].

In this multicentre retrospective study, we evaluated patients with a conventional pacemaker implanted for bradycardia indication or post-atrioventricular (AV) node ablation with high burden right ventricular pacing and patients with an existent primary/secondary prevention defibrillator with high burden right ventricular pacing or broad QRS complex and severely impaired LV systolic function and HF who underwent an upgrade to CRT. This observational study is the highest in terms of numbers of participants being evaluated.

2. Materials and Methods

Study design

This is the largest multicentre retrospective study so far that includes in total, 151 (93 upgrades to cardiac resynchronisation therapy – Pacemaker (CRT-P) and 58 upgrades to CRT-D) participants who had an upgrade to a CRT device between January 2010 and January 2020. Patient data were collected from Derriford, Lincoln and Milton Keynes Hospitals in the UK. Participants had their upgrade either at the time of their pacemaker generator box change or as an inpatient following admission with decompensated HF and severely impaired LV systolic dysfunction.

More than 100 patients were excluded from the study due to not meeting the inclusion criteria; they either had incomplete investigation or records were not available for analysis.

This was part of a multicentre national audit with the following registration numbers: CA_2022-23-281 and CA_2022-23-282.

Patient selection and sample size

All 151 participants in this study had their echocardiographic assessment performed by British Society of Echocardiography -accredited physiologists; device interrogations and optimisation were performed by a British Heart Rhythm Society-accredited physiologist; the decision to upgrade was either made by a consultant cardiologist or through an HF multi-disciplinary team.

Pacemaker interrogation

Participants reviewed in this study had a pre-upgrade pacemaker/ICD interrogation showing the percentage of RV pacing. Physical notes were analysed in those without electronic records to obtain the necessary information. A post-implant CRT interrogation was performed in all patients showing percentage BiV pacing.

Echocardiography

Only patients with an echocardiogram before the upgrade and at least 6–18 months thereafter were included in this study. Parameters, such as LVEF by Simpson’s biplane, left ventricle end diastolic volume (LVEDV), left ventricle end systolic volume (LVESV) and left ventricle internal dimension in diastole (LVIDd) were analysed before and after upgrade. Participants with incomplete echocardiographic assessments were excluded from the study.

Aetiology of LV dysfunction, NYHA classification, medication history, associated comorbidities and post-upgrade complications were recorded from patients electronic and/or physical notes.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA), together with the XLSTAT add-on for MS Excel (Addinsoft SARL, Paris, France). The descriptive analysis of the study group was performed with Excel, while normality tests (Anderson–Darling) and complex statistical tests (chi squared, Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon) were performed using XLSTAT.

Because most of the numerical variables recorded in our study did not have a normal (Gaussian) distribution, the nonparametric Mann–Whitney test was primarily used to detect significant differences between the values in the compared data series for patient groups.

Multivariate linear regression was used to compare the effects of aetiology, medication history, percentage right ventricular pacing (RVP) and comorbidities on post-upgrade NYHA and EF change.

3. Results

A total of 93 patients were upgraded from a conventional pacemaker to CRT, the sex ratio was 70% in favour of male patients (64 male and 29 female). The median age was 82±10 years old. There were 82 patients (88.17%) with >40% RVP and 11 (11.83%) patients with <40% RVP. Post-upgrade BiV pacing was >90 % in 93.55% of the participants. The distribution of patients based on aetiology of cardiomyopathy, medication history and associated comorbidities are listed in “

Table 1”.

The mean pre-upgrade QRS duration was 181±21 ms, compared to 114±15 ms after upgrade, showing a narrower QRS duration of at least 66±25 ms, which was a statistically significant difference with a P value <0.0001. The pre-upgrade LVESV was 121±33 ml and after upgrade was 84±33 ml with a post-upgrade decrease in LVESV of 36±24 ml; P value of 0.0001 showing significant statistical difference. The pre-upgrade LVIDd measured in 2M-mode was 5.6±0.7 cm compared to 5.1±0.7cm after upgrade, showing a decrease in LVIDd of 0.5±0.4 cm with a P value of 0.0011. The pre-upgrade mean LVEDV was 170±50 ml and post-upgrade LVEDV was 128±46 ml, with a median decrease in LVEDV of 41±29 ml and P value of 0.0003, showing a statistically significant difference. The mean LVEF before upgrade was 30±9% and 43±11% after upgrade, showing an increase in LVEF of 12±9%, which was statistically significant with a P value of 0.0002. The mean NYHA class before upgrade was II/III compared to a post-upgrade NYHA class of I/II, showing at least a one-grade classification decrease in NYHA class, which was statistically significant with a P value of <0.0001.

Patients who were on an angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor (ARNi) had a better LVEF before upgrade of 34±7% compared to 26±10% in those without ARNi and responded better (46±9%) compared to those without (40±11%), which was statistically significant with a P value of 0.0053.

Patients who were on an SGLT-2 inhibitor had a better LVEF before upgrade but there was no statistical difference; the same applied to those who were on a mineral receptor antagonist (MRA) and beta-blockers.

Patients with ischaemic heart disease had a similar pre-upgrade NYHA classification compared to those with non-ischaemic aetiology; however, patients with non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy had a greater decrease in NYHA class compared to ischaemic cardiomyopathy. Patients with ischaemic heart disease had a greater LVIDd before upgrade compared to those with non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy (5.8±0.5 cm versus 5.4±0.7 cm) with no statistical difference after upgrade. There was a greater increase in EF in patients with non-ischaemic heart disease compared to those with ischaemic heart disease; however, this was not statistically significant.

Analysis of upgrade to CRT-D participants

A total of 58 patients were included in the CRT-D upgrade, predominantly male (72%) with a median age of 76±10 years. Overall, 28 patients (48.28%) were RVP > 40% and 30 patients (51.72%) were <40% RVP. Full descriptions of the categorical variable are listed in “Table 2”. Percentage BiV pacing was similar to the permanent pacemaker (PPM) group. Overall, 72% of the patients were in sinus rhythm and 28% were in atrial arrhythmia; there was no statistically significant difference between those in sinus rhythm compared to those with atrial arrhythmia. The aetiology of cardiomyopathy was predominantly of ischaemic aetiology (72%) as expected. The mean pre-upgrade QRS duration was 170±25 ms, compared to after upgrade, which was 117±12 ms, showing a narrower QRS duration of at least 52±25 ms. Pre-upgrade LVESV was 151±47 ml and after upgrade this was 128±58 ml with a post-upgrade decrease in LVESV of 22±32 ml. Pre-upgrade LVIDd measured in 2M-mode was 6.3±0.9 cm compared to 5.9±1 cm after upgrade, showing a decrease in LVIDd of 0.38±0.53 cm. The pre-upgrade mean LVEDV was 220±69 ml and the post-upgrade LVEDV was 187±81 ml, with a median decrease in LVEDV of 32±56 ml. The mean LVEF before upgrade was 23±11 % and post-upgrade LVEF was 33±13%, showing an increase in LVEF of 10±14%. The mean NYHA class before upgrade was III/IV compared to a post-upgrade NYHA class of II/III, showing at least a one-grade classification decrease in NYHA class. The improvements in all the analysed parameters were statistically significant.

Patients treated with ARNi had a better pre-upgrade NYHA class but no significant echocardiographic improvement. On the other hand, patients treated with SGLT-2i showed statistically significant improvement LVIDd after upgrade as well as better NYHA class, whereas patients treated with MRA had a better post-upgrade LVESV decrease, better NYHA class, as well as improvement in EF.

Table 2.

Description of the categorical variables recorded for the CRT-D group.

Table 2.

Description of the categorical variables recorded for the CRT-D group.

| Dermographics |

- 3.

Male |

42 (73%) |

- 4.

Female |

16 (27%) |

| Underlying Ryhthm |

- 3.

Sinus |

42 (73%) |

- 4.

Atrial arryhthmia |

16 (33%) |

| Age |

76±10 years old |

| Aetiology |

- 5.

Ischaemic cardiomyopathy |

42 (72.4%) |

- 6.

Non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy |

11 (18.9%) |

- 7.

Inherited Cardiac Conditions |

9 (15.5%) |

- 8.

Valvular heart disease |

3 (5.17%) |

| Medication History |

- 5.

Beta-Blockers |

58 (100%) |

- 6.

Mineral receptor antagonists (MRA) |

44 (75.8%) |

- 7.

Angiotensin receptor-neprilysin Inhibitors ( ARNi) |

36 (62%) |

- 8.

Sodium-glucose transport protein 2 inhibitors ( SGLT-2) |

- 9.

-

33 (57%)

|

| Comorbidities |

- 4.

Diabetes |

29 (50%) |

- 5.

-

CKD stage

2.1: CKD Stage II

2.2: CKD stage IIIa

2.3: CKD stage IIIb

2.4 CKD stage IV

2.5 CKD Stage V

|

23 (39.6%)

19 (32.7%)

8 (13.8%)

6 (10.34%)

-

|

- 6.

Hypertension |

49 (84.5%) |

Statistical analysis comparing upgrade to CRT-P to CRT-D

The sex ratio was similar in both groups, close to 70% in favour of male patients. Patients with an upgrade to ICD were younger (median 76±10 years compared to 82±10 years in the CRT-P group). As expected, there was a high prevalence of patients with ischaemic cardiomyopathy in the ICD group, with a higher prevalence of non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy in PPM participants. Both groups had a similar distribution of the use of HF medication. Participants in the ICD group had a higher prevalence of diabetes compared to those in the PPM group. The distribution of the groups according to chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage was non-significant.

As expected, the PPM group had a higher percentage RVP compared to those with an ICD; multivariate linear regression analysis demonstrated that the post-upgrade increase in EF was higher in patients with RVP > 40% compared to those with RVP < 40% (44.34±10.57 versus 35.73±13.94%).

In the ICD group, a reduction in post-upgrade LVIDd was much higher in patients with a high percentage RVP (>40%) compared to <40% RVP (5.65±1.04 versus 6.21±1.06). The post-upgrade LVEDV reduction was similarly higher in patients with pre-upgrade high percentage RVP (165.82±70 versus 207.18±87.16). The post-upgrade EF in patients with >40 % pre-upgrade RVP was also better but this was not statistically significant at P = 0.4533.

The pre-upgrade QRS duration in CRT-P upgrade participants was higher compared to the CRD-D group mainly due to a high percentage of RV pacing in CRT-P versus CRT-D defined as >40% in this study (88.17% versus 48.28%). The mean pre-QRSD in the PPM group with RVP > 40% was 184.34±19.36 ms compared to those with RVP < 40%, which was 160.82±26.89 ms. The post-upgrade reduction in QRSD was higher in patients with a higher percentage RVP (69.28±24.62 ms) versus (47.27±24.29) in patients with RVP < 40%. These statistical analyses were similar in the ICD groups.

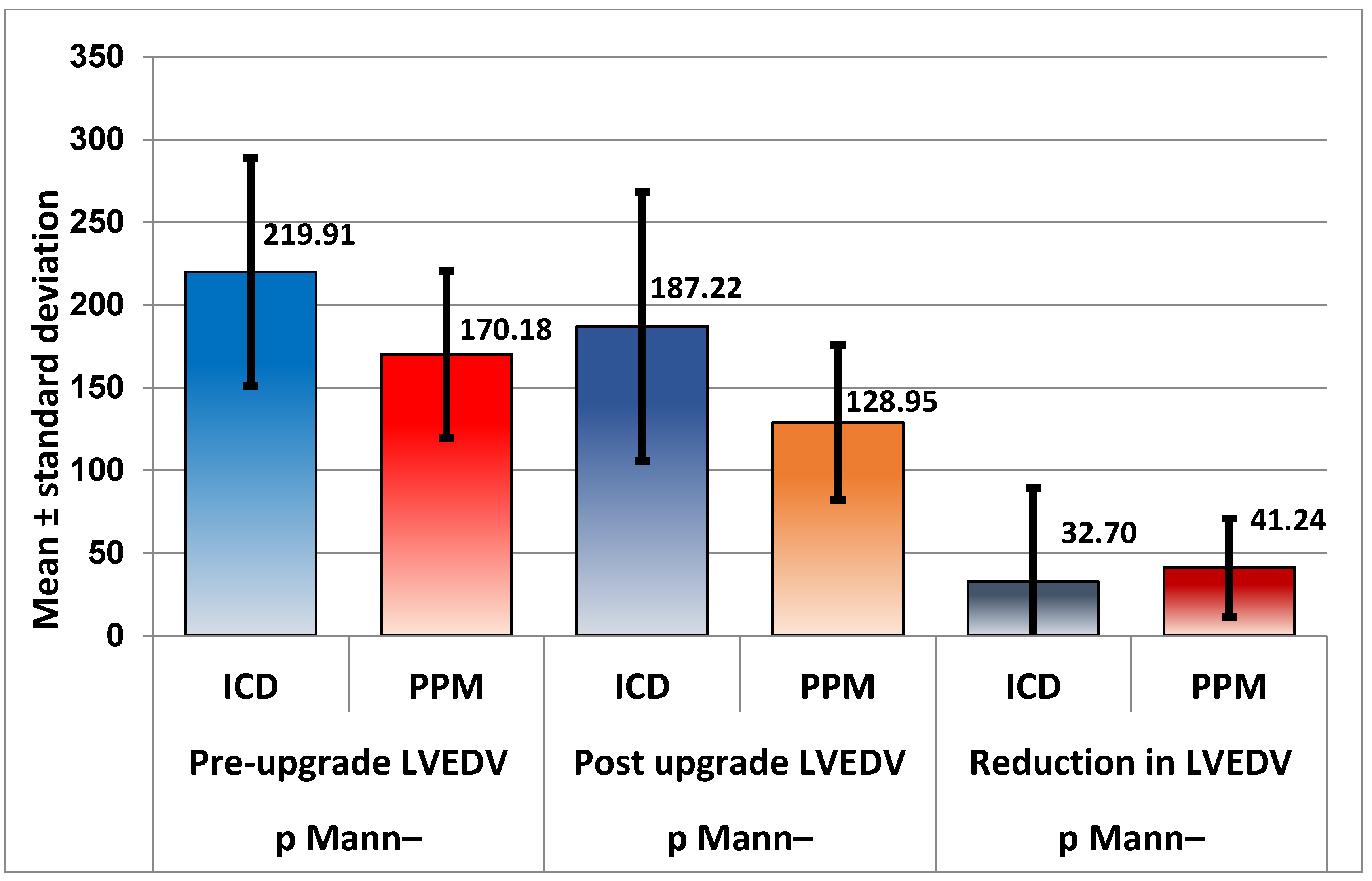

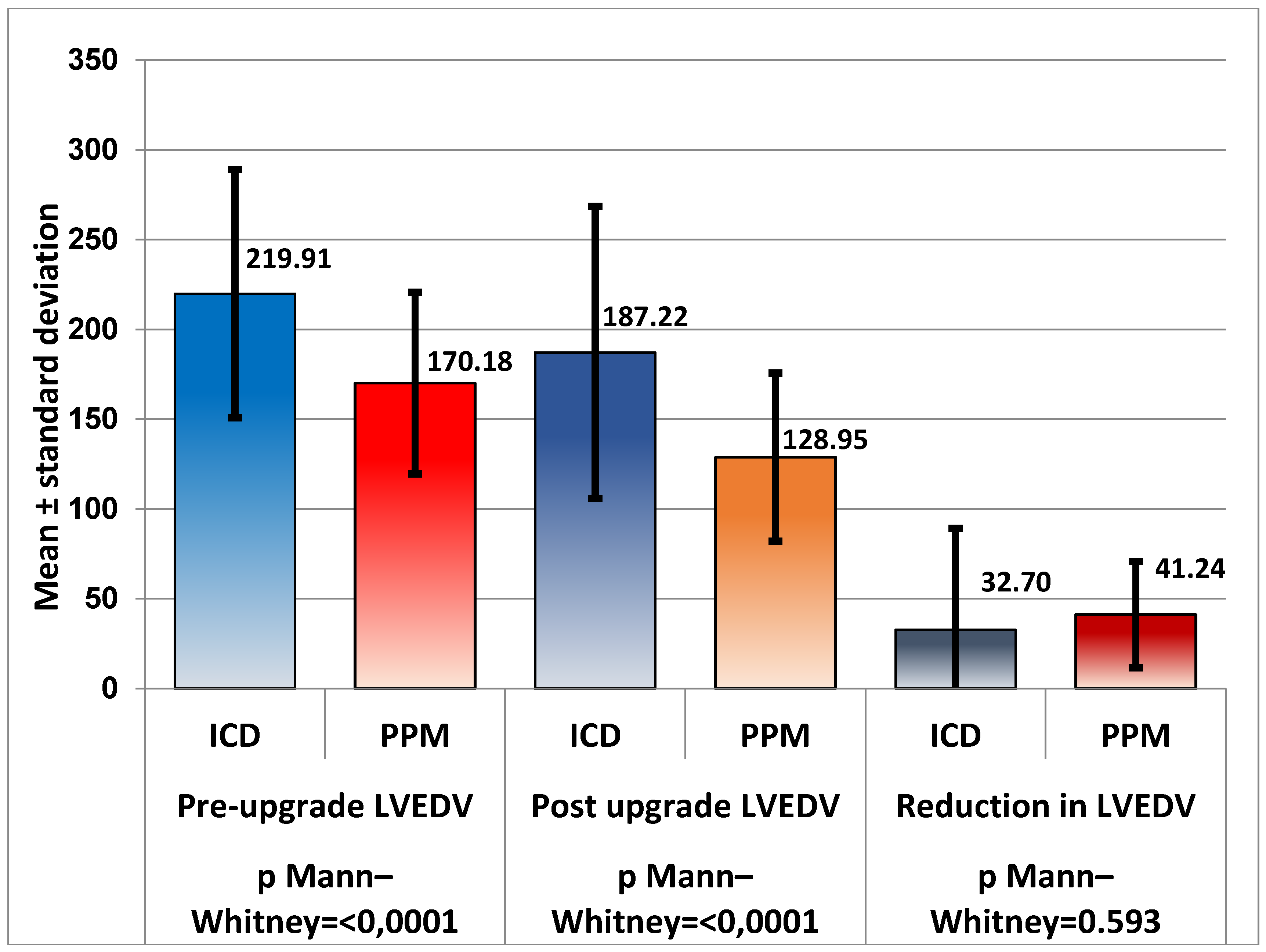

Echocardiography

Pre-upgrade LVESV in the ICD group was significantly higher than in the PPM group and participants in the PPM group had significantly better reduction in LVESV compared to those from the ICD group (22±32 ml in the CRT-D group versus 36±24 ml in the CRT-P group), P = 0.019, showing that participants in the CRT-P group respond better. The same applied to LVEDV; however, the post-upgrade reduction in LVEDV comparing the two groups was not statistically significant, P = 0.593.

The pre-upgrade LVIDd in patients with ICDs was higher than in those with PPM; however, although in both groups there was significant reduction in LVIDd after upgrade, the direct comparison between the two groups was not significant, P = 0.123.

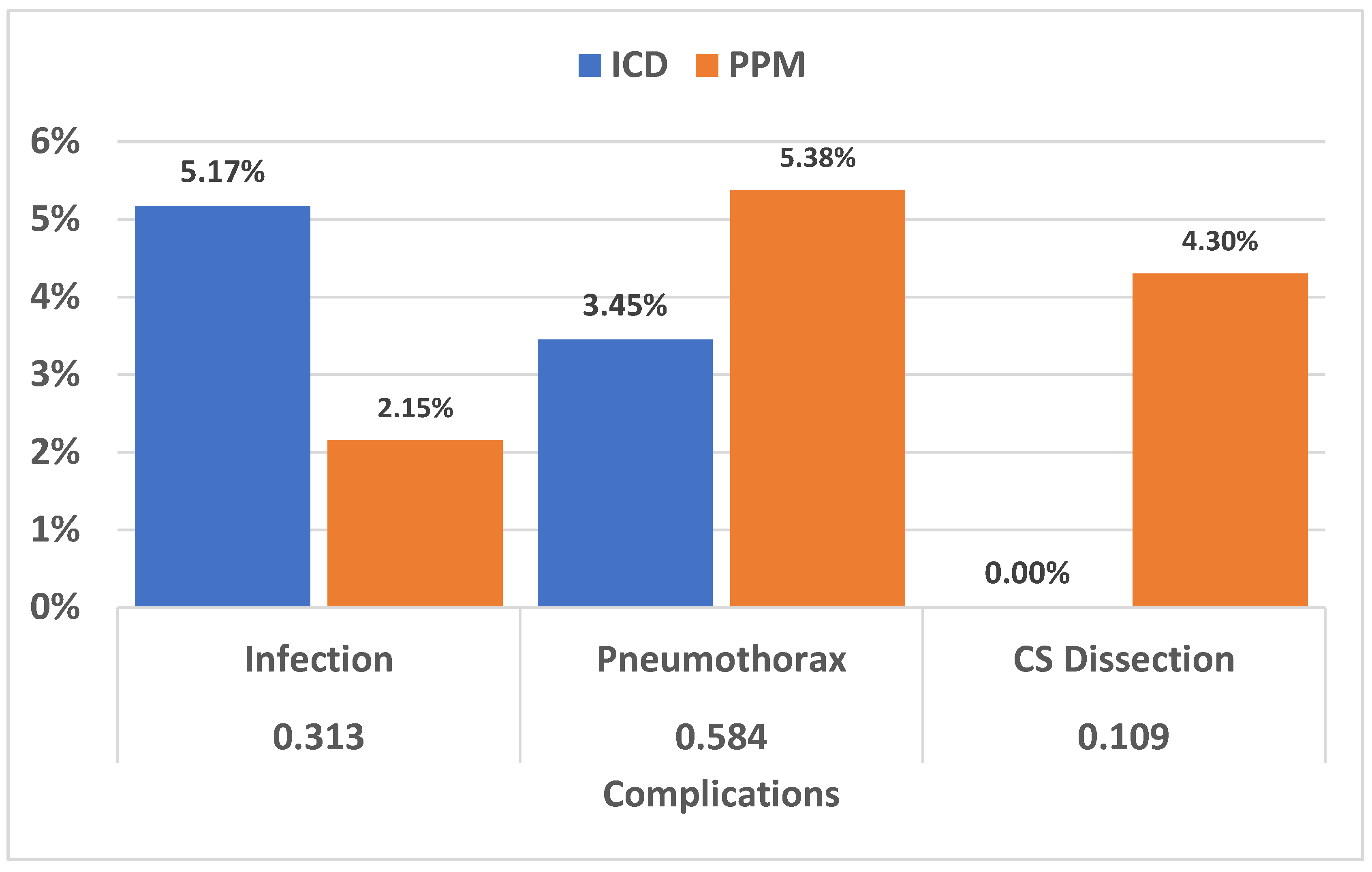

When it came to post-upgrade complications, there were three upgrades complicated with infection in the ICD group (5.17%) compared to two in the PPM group (2.15%), two cases of pneumothorax in CRT-D participants (3.45%) compared to five in the PPM group (5.38%) and zero cases of cardiac tamponade due to coronary sinus (CS) dissection in the ICD group compared to four in the CRT-P group (4.30%).

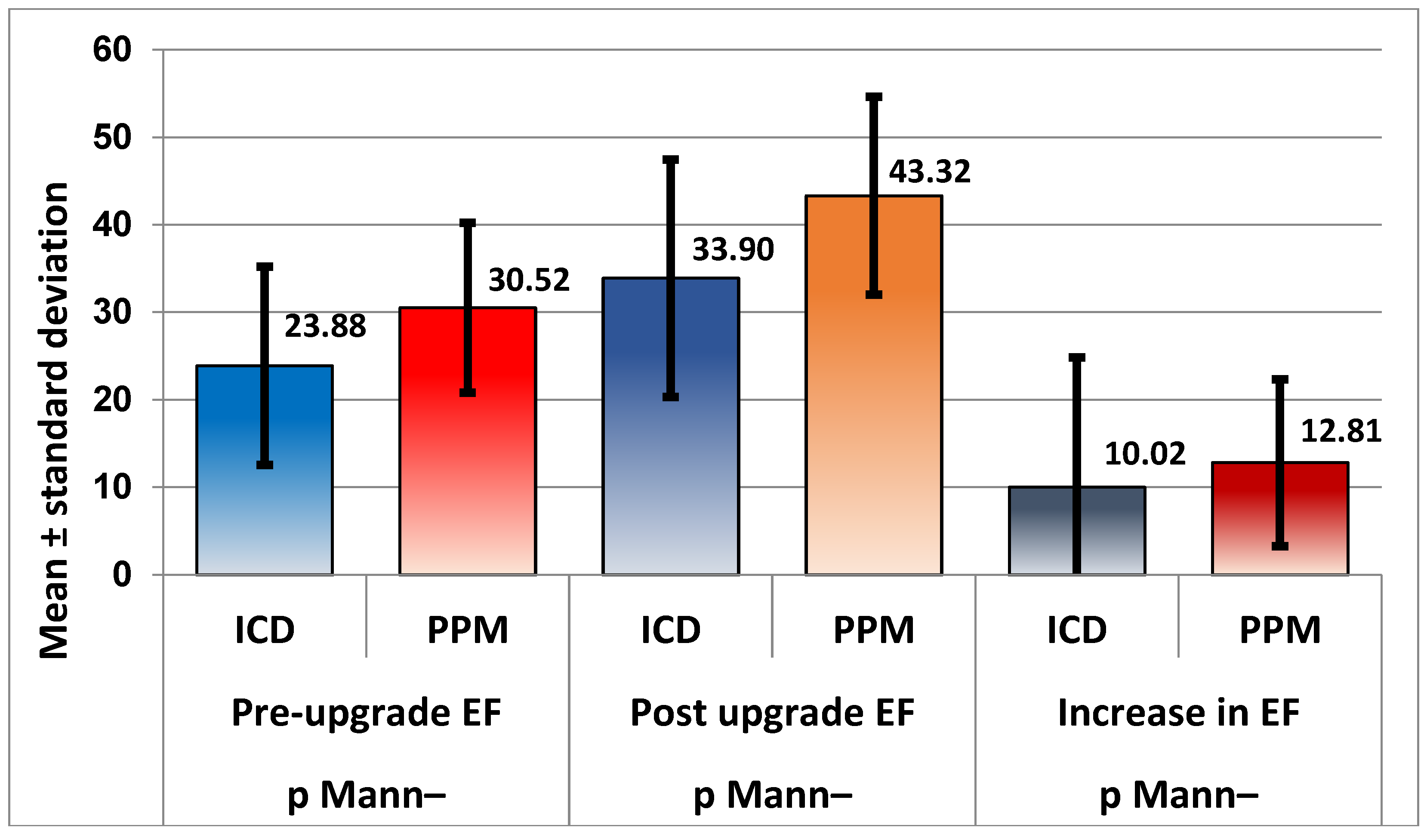

EF was significantly lower in the ICD group before upgrade compared to the PPM group (23±11% versus 30±9) and the post-upgrade increase in patients with CRT-P was significantly higher compared to the CRT-D group (10±14 versus 12.8±9.53), P = 0.032.

Patients in the ICD group were in a higher NYHA class before upgrade compared to the PPM group, and there was significant improvement in both groups after upgrade to CRT but a direct comparison was not statistically significant, P = 0.537.

Figure 1.

EF was greater in patients with PPM, with a highly significant level of confidence (P < 0.001) both before and after upgrade. Moreover, the increase in EF percentage was significantly greater in patients with PPM (P = 0.032; Mann–Whitney).

Figure 1.

EF was greater in patients with PPM, with a highly significant level of confidence (P < 0.001) both before and after upgrade. Moreover, the increase in EF percentage was significantly greater in patients with PPM (P = 0.032; Mann–Whitney).

Figure 2.

Patients with ICD have, on average, an NYHA class ranking greater than PPM patients, both before and after upgrade, the differences being statistically significant (P = 0.035 and 0.013, respectively), with an almost identical decrease in ranking (P = 0.537).

Figure 2.

Patients with ICD have, on average, an NYHA class ranking greater than PPM patients, both before and after upgrade, the differences being statistically significant (P = 0.035 and 0.013, respectively), with an almost identical decrease in ranking (P = 0.537).

Figure 3.

As expected, after comparing LVESV; LVEDV was also significantly greater in patients with ICD, both before and after upgrade (P < 0.001), but for LVEDV, the decrease was similar for the two groups. Even if PPM patients showed a greater decrease, the difference was not statistically significant, with the Mann–Whitney test returning P = 0.593.

Figure 3.

As expected, after comparing LVESV; LVEDV was also significantly greater in patients with ICD, both before and after upgrade (P < 0.001), but for LVEDV, the decrease was similar for the two groups. Even if PPM patients showed a greater decrease, the difference was not statistically significant, with the Mann–Whitney test returning P = 0.593.

Figure 4.

Even if there were differences between the occurrences of infection (5.17% versus 2.15%), pneumothorax (3.45% versus 5.38%) and CS dissection (0% versus 4.30%), the differences were not statistically significant, in all three cases the chi squared P value was >0.05.

Figure 4.

Even if there were differences between the occurrences of infection (5.17% versus 2.15%), pneumothorax (3.45% versus 5.38%) and CS dissection (0% versus 4.30%), the differences were not statistically significant, in all three cases the chi squared P value was >0.05.

4. Discussion

The study demonstrates that upgrades to BiV pacing have a similar risk of complications compared to de novo implant. This is close to the findings of a study conducted by Pothineni et al. [

19] and a survey by Bogale et al., comparing the outcomes between de novo implants with upgrades to CRT [

20].

Patients with ARNi had a better EF before upgrade in patients with non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy and had a greater increase in EF compared to those without ARNi. Participants from the ICD group who were on SGLT-2 had a greater reduction in LVIDd. Post-upgrade EF, NYHA class and LVESV were better in patients with CRT-D who were on an MRA. This makes a case for goal-directed therapy and the advancement of synergic medical optimisation in conjunction with CRT.

In summary, this study demonstrates the presence of adverse LV remodelling due to chronic RVP. Upgrade to CRT improved EF, reduced LVESV, LVEDV and LVIDd and led to a significant improvement in clinical NYHA class in both groups but a significantly higher improvement in CRT-P. These findings are very similar to a systematic review and meta-analysis performed by Kaza et al. in patients who had an upgrade to CRT [

21,

22].

5. Conclusions

These data show that the PPM group patients have a greater response to upgrade to CRT compared to those from the ICD group. This has been demonstrated in other trials but in patients with non-ischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) who seem to demonstrate an improved response to CRT driven by left bundle branch block (LBBB) electrical dyssynchrony over and above a poor underlying substrate. It also demonstrates that patients with non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy are better responders compared to those with ischaemic aetiology. One can make a case that a pure electrical dyssynchrony is more likely to respond if CRT demonstrates more native activation and this is the rationale for ongoing trials comparing CRT to conduction system pacing. As chronic RV pacing cardiomyopathy patients have no intrinsic muscle disease one would predict that they are more likely to be responders to effective CRT.

6. Limitations

This is a retrospective study with data available only on clinical and echocardiographic assessments of the patients before and after the upgrade. A useful tool would have been brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) measurement; however, most of the patients did not have the measurements taken before and after the upgrade to CRT. Another useful analysis would have been a 6-minute walk test; however, with the study undertaken during the COVID-19 pandemic, this proved to be impossible.

With the BUDAPEST-CRT trial to be published soon, we will have more answers on whether BiV pacing is truly superior to only RV pacing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Arsalan Farhangee and Ion Mindrila; methodology, Arsalan Farhangee, Mark Davies and Ion Minrila.; software, Arsalan Farhangee.; validation, Mark Davies, Ion Mindrila, David Morgan, Ben Sieniewics; formal analysis, Arsalan Farhangee, Ion Mindrila; investigation, Arsalan Farhangee.; resources, Arsalan Farhangee.; data curation, Arsalan Farhangee, Katie Gaughan and Robyn Meyrick; writing—original draft preparation, Arsalan Farhangee; writing—review and editing, Arsalan Farhangee, Mark Davies and Ion Mindrila.; visualization, Arsalan Farhangee.; supervision, Ion Mindrila.; project administration, Arsalan Farhangee; funding acquisition, none. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This was part of a multicentre national audit with the following registration numbers: CA_2022-23-281 and CA_2022-23-282.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to making part of a national audit.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the contributions made by the physiologist from Derriford Hospital, Lincoln County Hospital and Milton Keynes University Hospital.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Moss AJ, Hall WJ,. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy for the prevention of heart-failure events. N Engl J Med 2009;361(14):1329-38. PMID: 19723701. [CrossRef]

- Abraham WT, Fisher WG,. Multicenter InSync randomized clinical evaluation. Cardiac resynchronization in chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med 2002;346(24):1845-53. PMID: 12063368. [CrossRef]

- Higgins SL, Hummel JD. Cardiac resynchronization therapy for the treatment of heart failure in patients with intraventricular conduction delay and malignant ventricular tachyarrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42(8):1454-9. PMID: 14563591. [CrossRef]

- Abraham WT, Young JB. Effects of cardiac resynchronization on disease progression in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction, an indication for an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, and mildly symptomatic chronic heart failure. Circulation 2004;110(18):2864-8. PMID: 15505095. [CrossRef]

- Dewhurst MJ, Linker NJ. Current evidence and recommendations for cardiac resynchronisation therapy. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev 2014;3(1):9-14. PMID: 26835058; PMCID: PMC4711566. [CrossRef]

- Kosztin A, Vamos M. De novo implantation vs. upgrade cardiac resynchronization therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Fail Rev 2018;23(1):15-26. PMID: 29047028; PMCID: PMC5756552. [CrossRef]

- Scott PA, Whittaker A. Rates of upgrade of ICD recipients to CRT in clinical practice and the potential impact of the more liberal use of CRT at initial implant. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2012;35(1):73-80. PMID: 22054072. [CrossRef]

- European Society of Cardiology (ESC), European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), Brignole M, Auricchio A, Baron-Esquivias G, Bordachar P, et al. 2013 ESC guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy: the Task Force on Cardiac Pacing and Resynchronization Therapy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA). Europace 2013;15(8):1070-118. PMID: 23801827. [CrossRef]

- Glikson M, Nielsen JC. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(35):3427-3520. Erratum in: Eur Heart J 2022;43(17):1651. PMID: 34455430. [CrossRef]

- Merkely B, Kosztin A. Rationale and design of the BUDAPEST-CRT Upgrade Study: a prospective, randomized, multicentre clinical trial. Europace 2017;19(9):1549-1555. PMID: 28339581; PMCID: PMC5834067. [CrossRef]

- Fang F, Chan JY. Prevalence and determinants of left ventricular systolic dyssynchrony in patients with normal ejection fraction received right ventricular apical pacing: a real-time three-dimensional echocardiographic study. Eur J Echocardiogr 2010;11(2):109-18. PMID: 19933290. [CrossRef]

- Curtis AB, Worley SJ. Improvement in clinical outcomes with biventricular versus right ventricular pacing: the BLOCK HF Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67(18):2148-2157. PMID: 27151347. [CrossRef]

- Foley PW, Muhyaldeen SA. Long-term effects of upgrading from right ventricular pacing to cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with heart failure. Europace 2009;11(4):495-501. PMID: 19307283. [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich G, Steffel J. Upgrading to resynchronization therapy after chronic right ventricular pacing improves left ventricular remodelling. Eur Heart J 2010;31(12):1477-85. PMID: 20233792. [CrossRef]

- Marai I, Gurevitz O, Carasso S. Improvement of congestive heart failure by upgrading of conventional to resynchronization pacemakers. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2006 Aug;29(8):880-4. PMID: 16923005. [CrossRef]

- Kiehl EL, Makki T. Incidence and predictors of right ventricular pacing-induced cardiomyopathy in patients with complete atrioventricular block and preserved left ventricular systolic function. Heart Rhythm 2016;13(12):2272-2278. PMID: 27855853. [CrossRef]

- Anand IS, Carson P. Cardiac resynchronization therapy reduces the risk of hospitalizations in patients with advanced heart failure: results from the Comparison of Medical Therapy, Pacing and Defibrillation in Heart Failure (COMPANION) trial. Circulation 2009;119(7):969-77. PMID: 19204305. [CrossRef]

- Vamos M, Erath JW. Effects of upgrade versus de novo cardiac resynchronization therapy on clinical response and long-term survival: results from a multicenter study. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2017;10(2):e004471. PMID: 28202628. [CrossRef]

- Pothineni NVK, Gondi S. Complications of cardiac resynchronization therapy: comparison of safety outcomes from real-world studies and clinical trials. J Innov Card Rhythm Manag 2022;13(8):5121-5125. PMID: 36072440; PMCID: PMC9436403. [CrossRef]

- Bogale N, Witte K. The European Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy Survey: comparison of outcomes between de novo cardiac resynchronization therapy implantations and upgrades. Eur J Heart Fail 2011;13(9):974-83. PMID: 21771823. [CrossRef]

- Kaza N, Htun V. Upgrading right ventricular pacemakers to biventricular pacing or conduction system pacing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace 2023;25(3):1077-1086. PMID: 36352513; PMCID: PMC10062368. [CrossRef]

- Van Geldorp IE, Veernoy K. Beneficial effects of biventricular pacing in chronically right ventricular paced patients with mild cardiomyopathy. Europace 2010;12(2);223–229. [CrossRef]

- Foley PWX, Muhyaldeen SA. Long-term effects of upgrading from right ventricular pacing to cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with heart failure. Europace 2009;11(4):495–501. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).