Submitted:

07 June 2023

Posted:

07 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Job Obligations and Responsibilities of IVD International Salespeople

1.2. Effort–reward Imbalance

1.3. Health-Promoting Leadership and Health Climate

1.4. Positive mental health

1.5. Socio-demographic Characteristics

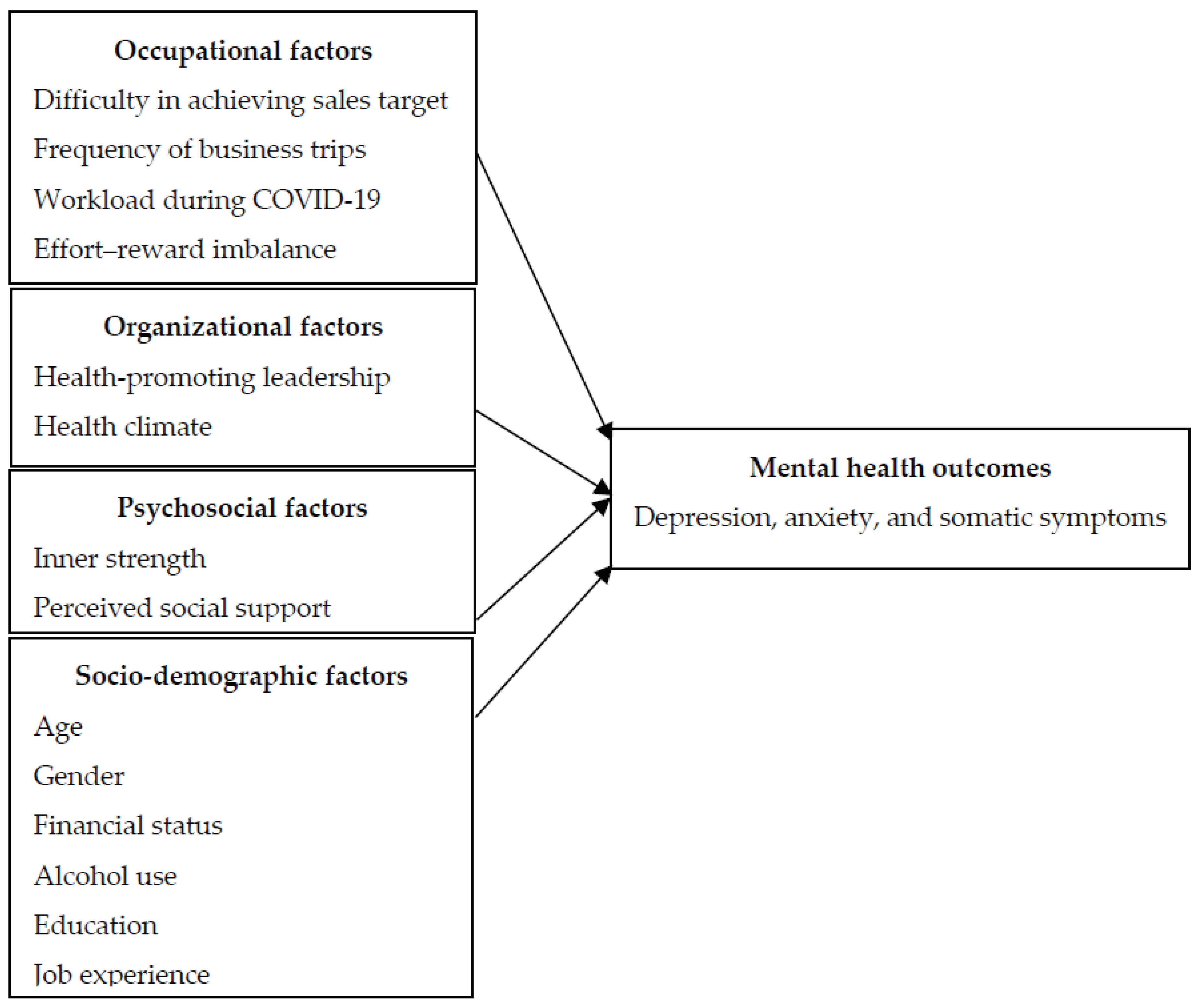

1.6. Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Measurements

2.4.1. Core Symptoms Index

2.4.2. Effort–reward Imbalance

2.4.3. Health-promoting Leadership

2.4.4. Health Climate

2.4.5. Inner Strength-Based Inventory

2.4.6. Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support

2.4.7. Characteristics of Participants

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Socio-demographic and Psychological Characteristics of Participants

3.2. Psychological Variables and Characteristics of Participants

| Variables | Mean (SD) or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, n (%) | |

| 18-24 | 34 (13.9) |

| 25-34 | 130 (53.3) |

| 35-44 | 67 (27.5) |

| 44-54 | 11 (4.5) |

| 54 and order | 2 (0.8) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 126 (51.6) |

| Female | 118 (48.4) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Single | 108 (44.3) |

| Married/living together/cohabiting | 134 (54.9) |

| Divorced/separated | 2 (0.8) |

| Educational, n (%) | |

| Bachelor’s degree or below | 195 (79.9) |

| Master’s degree or above | 49 (20.1) |

| Alcohol use, n (%) | |

| Yes | 100 (41.2) |

| No | 143 (58.8) |

| Job experience, n (%) | |

| Less than a year | 52 (21.4) |

| 1-3 years | 85 (35.0) |

| 4-6 years | 57 (23.4) |

| More than 6 years | 49 (20.2) |

| Financial status, n (%) | |

| Not enough income or incurring debt | 19 (7.8) |

| Barely sufficient income, adequate income without debt | 102 (41.8) |

| Enough income without savings | 56 (23.0) |

| Enough income with some savings | 67 (27.4) |

| Occupational factors | |

| Frequency of business trip, n (%) | |

| 0 trips/year | 98 (40.2) |

| 1–3 trips/year | 101 (41.4) |

| >3 trips/year | 45 (18.4) |

| Workload during COVID-19, n (%) | |

| Significantly decreased | 55 (22.5) |

| Decreased | 40 (16.4) |

| Not changed | 37 (15.2) |

| Increased | 74 (30.3) |

| Significantly increased | 38 (15.6) |

| Effort–reward imbalance (>1 imbalance), n (%) | 78 (32.0) |

| Sales target, n (%) | |

| Easily achievable | 74 (30.4) |

| Difficult to achieve | 152 (62.6) |

| Not achievable | 17 (7.0) |

| Organizational factors | |

| Health-promoting leadership (range 0–15) | 9.79 (2.63) |

| Health climate (range 0–25) | 17.21 (3.96) |

| Psychological factors | |

| Inner strength (range 10–50) | 31.18 (8.08) |

| Perceived social support–Total score (range 12–84) | 54.36 (13.44) |

| Perceived social support from significant others (mean scores range 1–7) | 4.43 (1.20) |

| Perceived social support from family members (mean scores range 1–7) | 4.48 (1.16) |

| Perceived social support from friends (mean scores range 1–7) | 4.57 (1.27) |

| Mental health outcomes, n (%) and mean (SD) | |

| CSI total score (range 0–60) | 12.89 (10.68) |

| CSI-depression score (range 0–18) | 4.69 (4.11) |

| CSI-anxiety score (range 0–13) | 3.81 (3.00) |

| CSI-somatization (somatic symptoms) (range 0–17) | 4.38 (4.32) |

| Major depression (CSI depression score≥9), n (%) | 45 (18.4) |

| Anxiety disorder (CSI anxiety score≥9), n (%) | 25 (10.2) |

| Variables | N (%) | CSI Total Score | Anxiety Score | Somatic Score | Major depression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean ± SD | p-Value | Mean ± SD | p-Value | Mean ± SD | p-Value | Non-MD N (%) |

MD N (%) |

p-Value | |

| 35 or older 18 –34 years |

80 (32.8) 164 (67.2) |

10.36 ± 9.88 14.13 ± 10.87 |

.009 | 2.98 ± 2.82 4.23 ± 3.20 |

.003 | 3.91 ± 4.23 4.61 ± 4.36 |

.238 | 71 (35.7) 128 (64.3) |

9 (20.0) 36 (80.0) |

.053 |

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male Female |

126 (51.6) 118 (48.4) |

10.05 ± 8.54 15.93 ± 11.88 |

<0.001 | 3.17 ± 2.49 4.51 ± 3.57 |

<0.001 | 3.34 ± 3.61 5.49 ± 4.74 |

<0.001 | 116 (58.3) 83 (41.7) |

10 (22.2) 35 (77.8) |

<0.001 |

| Marital status | ||||||||||

| In relationship Single |

134 (54.9) 110 (45.1) |

11.31 ± 10.14 14.82 ± 11.05 |

.010 | 3.36 ± 2.98 4.37 ± 3.23 |

.012 | 4.07 ± 4.34 4.76 ± 4.29 |

.211 | 113 (56.8) 86 (43.2) |

21 (46.7) 24 (53.3) |

.247 |

| Education | ||||||||||

| Bachelor’s degree or below Master’s degree or above |

195 (79.9) 49 (20.1) |

13.27 ± 10.84 11.41 ± 10.02 |

.277 | 3.85 ± 3.11 3.67 ± 3.23 |

.723 | 4.66 ± 4.41 3.27 ± 3.78 |

.043 | 158 (79.4) 41 (20.6) |

37 (82.2) 8 (17.8) |

.837 |

| Alcohol use | ||||||||||

| No Yes |

143 (58.8) 100 (41.2) |

12.20 ± 10.19 13.88 ± 11.39 |

.230 | 3.66 ± 2.95 4.06 ± 3.39 |

.326 | 4.10 ± 4.21 4.76 ± 4.49 |

.247 | 120 (60.6) 78 (39.4) |

23 (51.1) 22 (48.9) |

.246 |

| Job experience | ||||||||||

| More than 1 year Less than a year |

191 (78.6) 52 (21.4) |

12.25 ± 10.26 15.13 ±12.02 |

.085 | 3.67 ± 3.05 4.33 ± 3.41 |

.181 | 4.19 ± 4.19 5.08 ± 4.79 |

.190 | 165 (82.9) 34 (17.1) |

26 (59.1) 18 (40.9) |

<0.001 |

| Financial status | ||||||||||

| Sufficient income Insufficient income |

123 (50.4) 121 (49.6) |

11.01 ± 10.11 14.80 ± 10.95 |

.005 | 3.37 ± 2.98 4.26 ± 3.23 |

.026 | 3.77 ± 4.01 5.00 ± 4.55 |

.026 | 109 (54.8) 90 (45.2) |

14 (31.1) 31 (68.9) |

.005 |

| Frequency of business trip | ||||||||||

| 0 trips/year >1 trips/year |

199 (81.6) 45 (18.4) |

13.48 ± 10.81 10.29 ± 9.82 |

.070 | 3.98 ± 3.14 3.09 ± 3.03 |

.085 | 4.48 ± 4.35 3.96 ± 4.23 |

.466 | 158 (79.4) 41 (20.6) |

41 (91.1) 4 (8.9) |

.087 |

| Workload during COVID-19 | ||||||||||

| Decreased or not changed Increased |

132 (54.1) 112 (45.9) |

13.27 ± 10.24 12.45 ± 11.21 |

.055 | 3.80 ± 3.09 3.83 ± 3.19 |

.946 | 4.89 ± 4.10 3.78 ± 4.50 |

.044 | 105 (52.8) 94 (47.2) |

27 (60.0) 18 (40.0) |

.411 |

| Sales target | ||||||||||

| Easy to achieve Difficult or not achievable |

74 (30.5) 169 (69.5) |

12.28 ± 10.49 13.12 ± 10.81 |

.574 | 3.36± 3.06 4.00 ± 3.16 |

.143 | 4.89 ± 4.31 4.15 ± 4.33 |

.222 | 63 (31.7) 136 (68.3) |

11 (25.0) 33 (75.0) |

.470 |

| VARIABLE | CSI | Depression | Anxiety | Somatic | ERI | HPL | HC | SBI | MSPSS total | MSPSS—Family | MSPSS—Friends | MSPSS—SO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSI | 1 | |||||||||||

| Depression | .928** | 1 | ||||||||||

| Anxiety | .915** | .798** | 1 | |||||||||

| Somatic symptom | .926** | .763** | .778** | 1 | ||||||||

| ERI | .310** | .361** | .320** | .192** | 1 | |||||||

| HPL | -.092 | -.113 | -.085 | -.059 | -.126* | 1 | ||||||

| HC | -.115 | -.132* | -.053 | -.120 | -.096 | .743** | 1 | |||||

| SBI | -.300** | -.306** | -.278** | -.248** | -.240** | .537** | .534** | 1 | ||||

| MSPSS—Total | -.195** | -.186** | -.194** | -.166** | -.012 | .550** | .546** | .481** | 1 | |||

| MSPSS—family members | -.228** | -.237** | -.223** | -.176** | -.044 | .529** | .534** | .411** | .896** | 1 | ||

| MSPSS—friends | -.147* | -.128* | -.165** | -.121 | .014 | .490** | .449** | .421** | .932** | .816** | 1 | |

| MSPSS—significant others | -.163* | -.153* | -.164* | -.139* | -.035 | .535** | .549** | .469** | .921** | .726** | .781** | 1 |

3.3. Pearson’s Correlation among Psychological Variables

| Variable | Predictor | B | SE | β | P | 95% LL-CI | 95% UL-CI |

| CSI total score*** | Age Gender Marital status Financial status ERI–score SBI–score MSPSS–total score |

1.502 3.898 .021 -.233 7.132 -.217 -.091 |

1.497 1.285 1.416 1.328 1.352 .091 .053 |

.066 .183 .001 -.011 .312 -.164 -.114 |

.317 .003 .988 .861 .000 .018 .086 |

-1.447 1.366 -2.768 -2.849 4.468 -.395 -.195 |

4.451 6.430 2.809 2.384 9.795 -.038 .013 |

| Major depression** | Age Gender Job experience Financial status ERI–score SBI–score MSPSS–total score |

-.629 -1.399 -.725 -.083 -1.988 -.083 -.028 |

.501 .443 .441 .432 .434 .032 .016 |

1.875 4.052 2.065 1.086 7.303 .920 .973 |

.209 .002 .100 .848 .000 .009 .087 |

.703 1.702 .870 .465 3.119 .865 .942 |

5.003 9.647 4.900 2.535 17.103 .979 1.004 |

| Anxiety score*** | Age Gender Marital status Financial status ERI–score SBI–score MSPSS–total score |

.704 .813 -.011 -.236 1.958 -.059 -.029 |

.450 .386 .425 .399 .406 .027 .016 |

.106 .130 -.002 -.038 .292 -.152 -.124 |

.119 .036 .980 .554 .000 .031 .069 |

-.181 .053 -.848 -1.022 1.158 -.113 -.060 |

1.590 1.574 .827 .550 2.758 -.005 .002 |

| Somatic score*** | Gender Education Financial status Workload during COVID-19 ERI–score SBI–score MSPSS–total score |

1.508 -1.301 -.243 -1.056 2.454 -.078 -.023 |

.536 .647 .551 .542 .570 .038 .022 |

.175 -.121 -.028 -.122 .265 -.146 -.073 |

.005 .046 .659 .052 .000 .039 .289 |

.451 -2.576 -1.328 -2.123 1.332 -.153 -.067 |

2.565 -.025 .842 .011 3.577 -.004 .020 |

3.4. Factors Predicting Mental Health Outcomes in IVD International Salespeople

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lelliott, P.; Tulloch, S.; Boardman, J.; Harvey, S.; & Henderson, H. Mental health and work. 2008.

- OECD. Health at a Glance: Europe 2018: State of Health in the EU Cycle, OECD Publishing, Paris. ISBN 978-92-64-30335-5.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing: Summary of Results. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/mental-health/national-study-mental-health-and-wellbeing/latest-release#content (accessed on 21 January 2022).

- Zhuxiao. The relationship between Organizational Commitment and Metal Health in Import and Export Company Employee. Master's thesis, Ningbo University. 2008. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CMFD2011&filename=2010025913.nh (accessed on 11 January 2020).

- Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; yu, X.; Yan, J.; Yu, Y.; Kou, C.; Xu, X.; Lu, J.; Zhizhong, W.; He, S.; Xu, Y.; He, Y.; Li, T.; Guo, W.-J.; Tian, H.; Xu, G.; Xu, X.; Wu, Y. Prevalence of mental disorders in China: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. The Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li Qing, C. L. , [Employee Assistance Program (EAP): An Effective Way to Improve Employee Mental Health]. Journal of Minjiang University 2004, (02), 125–128. [Google Scholar]

- The Lancet Global Health, Mental health matters. The Lancet Global Health. Available online: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langlo/article/PIIS2214-109X(20)30432-0/fulltext (accessed on 8 November 2020).

- Dragioti, E.; Li, H.; Tsitsas, G.; Lee, K. H.; Choi, J.; Kim, J.; Choi, Y. J.; Tsamakis, K.; Estradé, A.; Agorastos, A.; Vancampfort, D.; Tsiptsios, D.; Thompson, T.; Mosina, A.; Vakadaris, G.; Fusar-Poli, P.; Carvalho, A. F.; Correll, C. U.; Han, Y. J.; Park, S.; Il Shin, J.; Solmi, M. A large-scale meta-analytic atlas of mental health problems prevalence during the COVID-19 early pandemic. J Med Virol 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Yan, L.; Ding, X.; Gan, Y.; Kohn, N.; Wu, J. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general Chinese population: Changes, predictors and psychosocial correlates. Psychiatry Res 2020, 293, 113396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Monetary Fund, Global Economic Growth Slows Amid Gloomy and More Uncertain Outlook. Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, Ed. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2022/07/26/blog-weo-update-july-2022 (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- World Health Organization, Mental health at work. 28 September 2022; Vol. 2023. 28 September.

- Vashist, S. K. , In Vitro Diagnostic Assays for COVID-19: Recent Advances and Emerging Trends. Diagnostics (Basel) 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjivan Gill; O. S. In Vitro Diagnostics IVD Market Research Report. Available online: https://www.marketresearchengine.com/reportdetails/global-in-vitro-diagnostics-ivd-market# (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- Kalorama Information. 2021 IVD Market Update and COVID-19 Impact. Bruce Carlson.,: 2021; Vol. 21-016.

- Erbach, G. In vitro diagnostic medical devices. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2014/542151/EPRS_BRI (accessed on 16 October 2020).

- O'Connor, B.; Pollner, F.; Fugh-Berman, A. Salespeople in the Surgical Suite: Relationships between Surgeons and Medical Device Representatives. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0158510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wondfo Biotech. Guangzhou Wondfo Biotech Co., Ltd. 2021 Annual Report; 2022.

- Atif, M.; Bashir, A.; Saleem, Q.; Hussain, R.; Scahill, S.; Babar, Z. U. Health-related quality of life and depression among medical sales representatives in Pakistan. Springerplus 2016, 5, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S. B.; Meena, J. S.; Sb, P.; Js, M. Work Induced Stress among Medical Representatives in Aurangabad City, Maharashtra. National journal of community medicine 2013, 4, 277–281. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Ding, M.; Pu, X.; Xie, C. [Mental health status of 239 foreign employees in Guangzhou]. South China J Prev Med. 2011, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Pensri, P.; Janwantanakul, P.; Chaikumarn, M. Prevalence of self-reported musculoskeletal symptoms in salespersons. Occup Med (Lond) 2009, 59, 499–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkholder, J. D.; Joines, R.; Cunningham-Hill, M.; Xu, B. Health and well-being factors associated with international business travel. J Travel Med 2010, 17, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for disease control and prevention. Sleep and Sleep Disorders. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/sleep/index.html (accessed on 11 March 2022).

- Siegrist, J.; Wahrendorf, M. Work Stress and Health in a Globalized Economy: The Model of Effort-Reward Imbalance. 2016.

- Ren, C.; Li, X.; Yao, X.; Pi, Z.; Qi, S. Psychometric Properties of the Effort-Reward Imbalance Questionnaire for Teachers (Teacher ERIQ). Front Psychol 2019, 10, 2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Y. Q.; Li, S.; Wang, J.; Liu, X. M.; Ren, J.; Wang, C. Association of occupational stress with job burnout and depression tendency in workers in Internet companies. Zhonghua Lao Dong Wei Sheng Zhi Ye Bing Za Zhi 2018, 36, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M. P. Early predictors of job burnout and engagement. J Appl Psychol 2008, 93, 498–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, L.; Li, P.; Wildy, H. Health-Promoting Leadership: Concept, Measurement, and Research Framework. Frontiers in Psychology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bregenzer, A.; Felfe, J.; Bergner, S.; Jiménez, P. How followers’ emotional stability and cultural value orientations moderate the impact of health-promoting leadership and abusive supervision on health-related resources. German Journal of Human Resource Management 2019, 33, 307–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, F.; Felfe, J.; Pundt, A. The Impact of Health-Oriented Leadership on Follower Health: Development and Test of a New Instrument Measuring Health-Promoting Leadership. German Journal of Human Resource Management 2014, 28, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonderlin, R.; Schmidt, B.; Müller, G.; Biermann, M.; Kleindienst, N.; Bohus, M.; Lyssenko, L. Health-Oriented Leadership and Mental Health From Supervisor and Employee Perspectives: A Multilevel and Multisource Approach. Frontiers in Psychology 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Song, Z.; Xiao, J.; Chen, P. How and When Health-Promoting Leadership Facilitates Employee Health Status: The Critical Role of Healthy Climate and Work Unit Structure. Frontiers in Psychology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuang, L. [Influencing Mechanism of Health-Promoting Leadership on Health Human Capital]. Southwestern University of Finance and Economics, 2018.

- Goetzel, R. Z.; Ozminkowski, R. J. The health and cost benefits of work site health-promotion programs. Annu Rev Public Health 2008, 29, 303–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crump, C. E.; Earp, J. A.; Kozma, C. M. Hertz-Picciotto, I., Effect of organization-level variables on differential employee participation in 10 federal worksite health promotion programs. Health Educ Q 1996, 23, 204–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribisl, K. M.; Reischl, T. M. Measuring the climate for health at organizations. Development of the worksite health climate scales. J Occup Med 1993, 35, 812–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buddhaghosa, B. The path of purification (Visuddhimagga). Available online: https://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/nanamoli/PathofPurification2011.pdf. (accessed on 16 March 2021).

- Seligman, M. E. P.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist 2000, 55, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongpakaran, N.; Wongpakaran, T. Strength-Based Therapy (SBT): Incorporation of the ‘Great Human Strength’ concept within the psychotherapy model. 2013.

- Boman, E.; Gustafson, Y.; Häggblom, A. Santamäki Fischer, R.; Nygren, B., Inner strength - associated with reduced prevalence of depression among older women. Aging Ment Health 2015, 19, 1078–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viglund, K.; Jonsén, E.; Strandberg, G.; Lundman, B.; Nygren, B. Inner strength as a mediator of the relationship between disease and self-rated health among old people. J Adv Nurs 2014, 70, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongpakaran, N.; Wongpakaran, T.; Kuntawong, P. Development and validation of the (inner) Strength-Based Inventory. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 2020, 23, 263–273. [Google Scholar]

- Pongpitpitak, N.; Wongpakaran, N.; Wongpakaran, T.; Nuansri, W. Buffering Effect of Perseverance and Meditation on Depression among Medical Students Experiencing Negative Family Climate. Healthcare (Basel) 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petkari, E.; Ortiz-Tallo, M. Towards Youth Happiness and Mental Health in the United Arab Emirates: The Path of Character Strengths in a Multicultural Population. Journal of Happiness Studies 2018, 19, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brummett, B. H.; Mark, D. B.; Siegler, I. C.; Williams, R. B.; Babyak, M. A. Clapp-Channing, N. E.; Barefoot, J. C., Perceived social support as a predictor of mortality in coronary patients: effects of smoking, sedentary behavior, and depressive symptoms. Psychosom Med 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sand, G.; Miyazaki, A. The impact of social support on salesperson burnout and burnout components. Psychology and Marketing 2000, 17, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y. J.; Jung, W. C.; Kim, H.; Cho, S. S. Association of Emotional Labor and Occupational Stressors with Depressive Symptoms among Women Sales Workers at a Clothing Shopping Mall in the Republic of Korea: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J. J.; Kim, J. Y.; Chang, S. J.; Fiedler, N.; Koh, S. B.; Crabtree, B. F.; Kang, D. M.; Kim, Y. K.; Choi, Y. H. Occupational stress and depression in Korean employees. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2008, 82, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M. B.; Gjerstad, J.; Frone, M. Alcohol use among Norwegian workers: associations with health and well-being. Occup Med (Lond) 2018, 68, 96–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, A.; Van de Velde, S.; Vilagut, G.; de Graaf, R.; O'Neill, S.; Florescu, S.; Alonso, J.; Kovess-Masfety, V. Gender differences in mental disorders and suicidality in Europe: results from a large cross-sectional population-based study. J Affect Disord 2015, 173, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, C. P.; Asnaani, A.; Litz, B. T.; Hofmann, S. G. Gender differences in anxiety disorders: prevalence, course of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness. J Psychiatr Res 2011, 45, 1027–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Medical Products Administration. Situation of Chinese medical device manufacturers in 2020. 2020.

- Wongpakaran, N.; Wongpakaran, T.; Lertkachatarn, S.; Sirirak, T.; Kuntawong, P. Core Symptom Index (CSI): testing for bifactor model and differential item functioning. Int Psychogeriatr 2019, 31, 1769–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siergist, J. Adverse health effects of high effort-low reward conditions at work. J Occup Health Psychol 1996, 1, 27–43. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.; Li. J. Measurement of psychosocial factors in the workplace—application of two occupational stress detection model. Chinese Journal of Occupational Health and Occupational Diseases 2004, 6, 22–26.

- Dai, J.; Yu, H., Wu, J., Fu, H. [Development of a concise occupational stress questionnaire and construction of an assessment model]. Fudan Journal (Medical Edition) 2007, 5, 656–661.

- Yu, H. [An Empirical Study on Job Burnout from the Aspect of Effort-Reward Imbalance East China University of Science and Technology], 2013.

- Köppe, C.; Kammerhoff, J.; Schütz, A. Leader-follower crossover: exhaustion predicts somatic complaints via StaffCare behavior. Journal of Managerial Psychology 2018, 33, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B. [Health-Promotion Leadership: Its Definition, Measurement and Effect on Employees’ Health]. China Human Resource Development 2016, 15, 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Basen-Engquist, K.; Hudmon, K. S.; Tripp, M.; Chamberlain, R. Worksite health and safety climate: scale development and effects of a health promotion intervention. Prev Med 1998, 27, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimet, G. D.; Dahlem, N. W.; Zimet, S. G.; & Farley, G. K. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Journal of Personality Assessment 1988, 52, 30–41.

- Wang, X.; Wang. X.; Ma H. [An updated version of the Manual of Mental Health Rating Scale]. Beijing: Chinese Journal of Mental Health 1999, 131–133.

- Lei, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, X. [The influence of social support on depression in adolescents: an analysis of moderated mediating effects]. Psychological Monthly 2022, 17, 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Meng, H.; Zhong, W. [Employees’ Core Self-evaluation and Life Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Perceived Social Support]. Journal of Psychological Science 2014, 37, 1232–1237. [Google Scholar]

- Cotrin, P.; Moura, W.; Gambardela-Tkacz, C. M.; Pelloso, F. C.; Santos, L. D.; Carvalho, M. D. B.; Pelloso, S. M.; Freitas, K. M. S. Healthcare Workers in Brazil during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Online Survey. Inquiry 2020, 57, 46958020963711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, B. J.; Li, G.; Chen, W.; Shelley, D.; Tang, W. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation during the Shanghai 2022 Lockdown: A cross-sectional study. J Affect Disord 2023, 330, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, Y.; Ma, J.; Wu, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, H.; Hall, B. J. Immediate and delayed psychological effects of province-wide lockdown and personal quarantine during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Psychol Med 2022, 52, 1321–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aknin, L. B.; Andretti, B.; Goldszmidt, R.; Helliwell, J. F.; Petherick, A.; De Neve, J. E.; Dunn, E. W.; Fancourt, D.; Goldberg, E.; Jones, S. P.; Karadag, O.; Karam, E.; Layard, R.; Saxena, S.; Thornton, E.; Whillans, A.; Zaki, J. Policy stringency and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal analysis of data from 15 countries. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e417–e426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian Z. China to Remove Quarantine for Inbound Travelers Starting January 8, 2023. China Briefing December 27, 2022. 8 January.

- Xu, W.; Tan, W.; Li, X.; Huang, Z.; Zheng, H.; Hou, C.; Jia, F.; Wang, S. Prevalence and correlates of depressive and anxiety symptoms among adults in Guangdong Province of China: A population-based study. Journal of Affective Disorders 2022, 308, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R. L.; Williams, J. B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wei, Y.; Zeng, L.; Yang, J.; Li, Y.; Song, X.; Li, H.; He, H.; Li, T.; Wu, K.; Yang, M.; Wu, F.; Ning, Y.; Zhang, X. Differences in the Association of Anxiety, Insomnia and Somatic Symptoms between Medical Staff and the General Population During the Outbreak of COVID-19. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2021, 17, 1907–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; H, J.; Tsai, W.; Kodish, T.; Trung, L. T.; Lau, A. S.; Weiss, B. Cultural variation in temporal associations among somatic complaints, anxiety, and depressive symptoms in adolescence. J Psychosom Res 2019, 124, 109763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalibatseva, Z.; Leong, F.; T, L. Cultural Factors, Depressive and Somatic Symptoms Among Chinese American and European American College Students. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 2018, 49, 1556–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. Depression and Culture - A Chinese Perspective. Canadian Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy 2007, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Bekhuis, E.; Boschloo, L.; Rosmalen, J. G.; Schoevers, R. A. Differential associations of specific depressive and anxiety disorders with somatic symptoms. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2015, 78, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lallukka, T.; Mekuria, G. B.; Nummi, T.; Virtanen, P.; Virtanen, M.; Hammarström, A. Co-occurrence of depressive, anxiety, and somatic symptoms: trajectories from adolescence to midlife using group-based joint trajectory analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Mental Health. Depression. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Farhane-Medina, N. Z.; Luque, B.; Tabernero, C.; Castillo-Mayén, R. Factors associated with gender and sex differences in anxiety prevalence and comorbidity: A systematic review. Science Progress 2022, 105, 00368504221135469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Droogenbroeck, F.; Spruyt, B.; Keppens, G. Gender differences in mental health problems among adolescents and the role of social support: results from the Belgian health interview surveys 2008 and 2013. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delisle, V. C.; Beck, A. T.; Dobson, K. S.; Dozois, D. J.; Thombs, B. D. Revisiting gender differences in somatic symptoms of depression: much ado about nothing? PLoS One 2012, 7, e32490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, C.; Angst, J. The Zurich Study. XII. Sex differences in depression. Evidence from longitudinal epidemiological data. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1992, 241, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, B. Gender differences in the prevalence of somatic versus pure depression: a replication. Am J Psychiatry 2002, 159, 1051–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Xiong, Y.; Michaëlsson, M.; Michaëlsson, K.; Larsson, S. C. Genetically predicted education attainment in relation to somatic and mental health. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 4296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang-Quan, H.; Zheng-Rong, W.; Yong-Hong, L.; Yi-Zhou, X.; Qing-Xiu, L. Education and risk for late life depression: a meta-analysis of published literature. Int J Psychiatry Med 2010, 40, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E. L.; Howe, L. D.; Wade, K. H.; Ben-Shlomo, Y.; Hill, W. D.; Deary, I. J.; Sanderson, E. C.; Zheng, J.; Korologou-Linden, R.; Stergiakouli, E.; Davey Smith, G.; Davies, N. M.; Hemani, G. Education, intelligence and Alzheimer's disease: evidence from a multivariable two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Int J Epidemiol 2020, 49, 1163–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, N. M.; Hill, W. D.; Anderson, E. L.; Sanderson, E.; Deary, I. J.; Davey Smith, G. Multivariable two-sample Mendelian randomization estimates of the effects of intelligence and education on health. Elife 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roche. Sales Representative- Diagnostic. Available online: https://careers.roche.com/global/en/job/ROCHGLOBAL202305111374EXTERNALENGLOBAL/Sales-Representative-Diagnostic (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Dixon, J. M.; Banwell, C.; Strazdins, L.; Corr, L.; Burgess, J. Flexible employment policies, temporal control and health promoting practices: A qualitative study in two Australian worksites. PLoS ONE 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halpern, D. How time-flexible work policies can reduce stress, improve health, and save money. Stress and Health 2005, 21, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, X.; Gao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Ge, H.; Sun, X.; Ma, X.; Liu, J. Associations of occupational stress with job burn-out, depression and hypertension in coal miners of Xinjiang, China: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e036087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackmore, E.; Stansfeld, S.; Weller, I.; Munce, S.; Zagorski, B.; Stewart, D. Major Depressive Episodes and Work Stress: Results From a National Population Survey. American journal of public health 2007, 97, 2088–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keser, A.; Li, J.; Siegrist, J. Examining Effort–Reward Imbalance and Depressive Symptoms Among Turkish University Workers. Workplace Health & Safety 2018, 67, 131–136. [Google Scholar]

- Zweber, Z. M.; Henning, R. A.; Magley, V. J. A practical scale for Multi-Faceted Organizational Health Climate Assessment. J Occup Health Psychol 2016, 21, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, H.; Zacher, H.; Lippke, S. The Importance of Team Health Climate for Health-Related Outcomes of White-Collar Workers. Front Psychol 2017, 8, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S.; Pundt, A. Organisational health behavior climate: Organisations can encourage healthy eating and physical exercise. Applied Psychology 2016, 65, 259–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boman, E.; Gustafson, Y.; Häggblom, A.; Santamäki Fischer, R.; Nygren, B. Inner strength – associated with reduced prevalence of depression among older women. Aging & Mental Health 2015, 19, 1078–1083. [Google Scholar]

- Wongpakaran, T.; Yang, T.; Varnado, P.; Siriai, Y.; Mirnics, Z.; Kövi, Z.; Wongpakaran, N. The development and validation of a new resilience inventory based on inner strength. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moe, A.; Hellzen, O.; Ekker, K.; Enmarker, I. Inner strength in relation to perceived physical and mental health among the oldest old people with chronic illness. Aging Ment Health 2013, 17, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundman, B.; Aléx, L.; Jonsén, E.; Norberg, A.; Nygren, B.; Santamäki Fischer, R.; Strandberg, G. Inner strength--a theoretical analysis of salutogenic concepts. Int J Nurs Stud 2010, 47, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamanian, H.; Amini-Tehrani, M.; Jalali, Z.; Daryaafzoon, M.; Ala, S.; Tabrizian, S.; Foroozanfar, S. Perceived social support, coping strategies, anxiety and depression among women with breast cancer: Evaluation of a mediation model. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2021, 50, 101892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eom, C. S.; Shin, D. W.; Kim, S. Y.; Yang, H. K.; Jo, H. S.; Kweon, S. S.; Kang, Y. S.; Kim, J. H.; Cho, B. L.; Park, J. H. Impact of perceived social support on the mental health and health-related quality of life in cancer patients: results from a nationwide, multicenter survey in South Korea. Psychooncology 2013, 22, 1283–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saikkonen, S.; Karukivi, M.; Vahlberg, T.; Saarijärvi, S. Associations of social support and alexithymia with psychological distress in Finnish young adults. Scand J Psychol 2018, 59, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrech, A.; Riedel, N.; Li, J.; Herr, R. M.; Mörtl, K.; Angerer, P.; Gündel, H. The long-term impact of a change in Effort–Reward imbalance on mental health—results from the prospective MAN-GO study. European Journal of Public Health 2017, 27, 1021–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faber, J.; Fonseca, L. M. How sample size influences research outcomes. Dental Press J Orthod 2014, 19, 27–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).