Submitted:

07 June 2023

Posted:

08 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- What is the most frequently used type of clause interdependence in both groups?

- Do children with SLI/DLD exhibit similar patterns of development in different types of clause interdependence compared to children with TD, from a longitudinal perspective?

- Are there significant differences in the use of clause interdependence relationships between children with SLI/DLD and TD in each grade, from a cross-sectional perspective?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

| AGE | GENDER | SCHOOL TYPE* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1° | 2° | 4° | female | male | public | private | |

| SLI/DLD | 6.7 | 7.7 | 9.7 | 10 | 14 | 21 | 3 |

| TD | 6.5 | 7.5 | 9.5 | 10 | 14 | 21 | 3 |

2.2. Procedure

| Clauses | Types of taxis | Clause complex |

|---|---|---|

| Simplex | ||

| Hypotaxis | ||

| Parataxis | ||

| Time-related parataxis | ||

|

La ardillita solo miraba por la ventana. * (The little squirrel just looked out the window.) |

Simplex | 1 |

|

No podía salir de su casita ese día (She couldn't leave his house that day) |

2 | |

|

ni jugar con los amiguitos (nor play with friends) |

Parataxis | |

|

porque estaba muy gorda, gorda (because she was very fat, fat) |

Hypotaxis | |

|

y se puso muy triste (and she became very sad) |

Time-related parataxis | |

|

porque no podía salir (because she couldn’t go out) |

Hypotaxis | |

|

y ahí la llamaban los animalitos (and the little animals called her) |

Time-related parataxis | |

|

y ella no podía salir y eso. (and she couldn’t get out and so). |

Time-related parataxis |

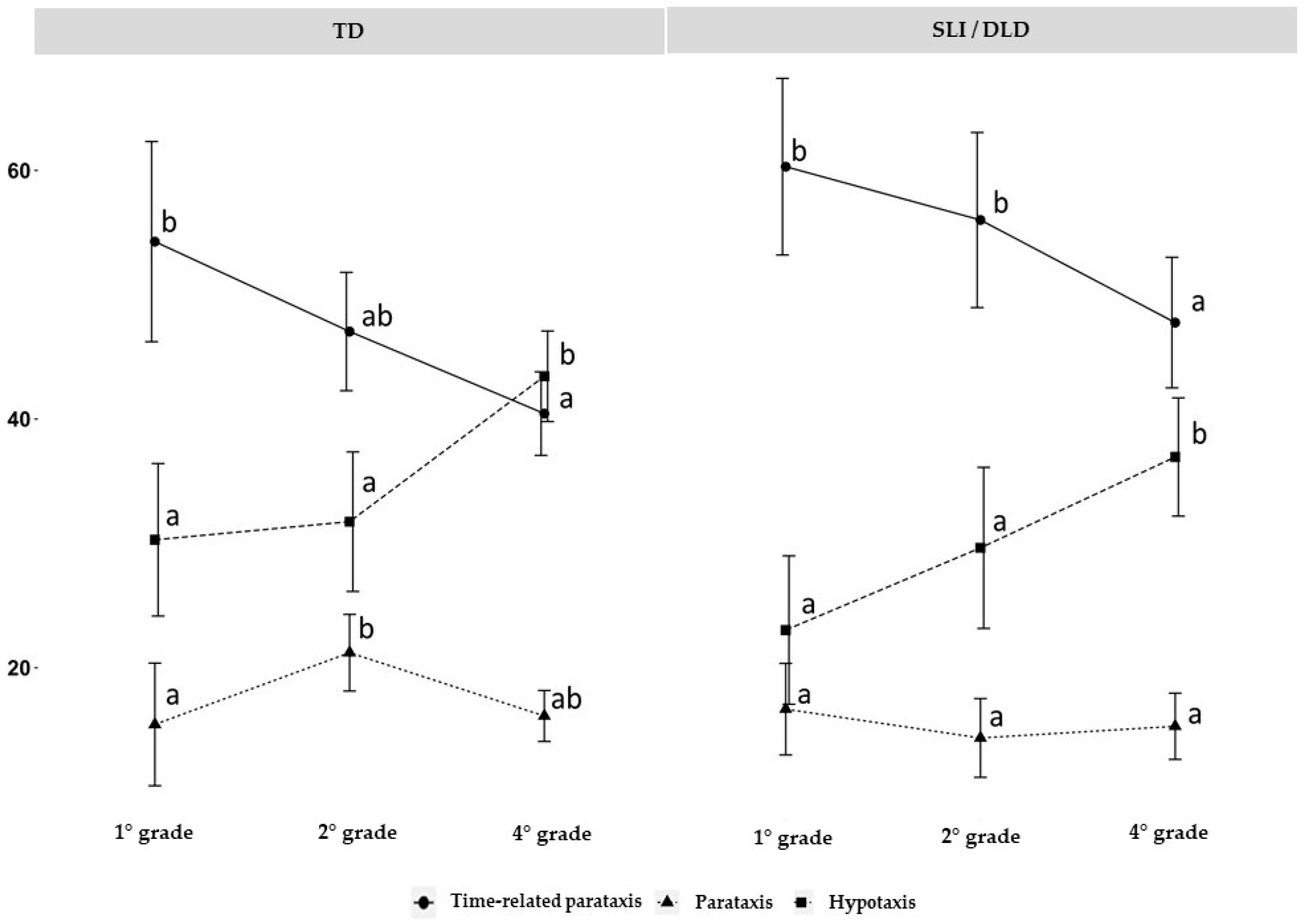

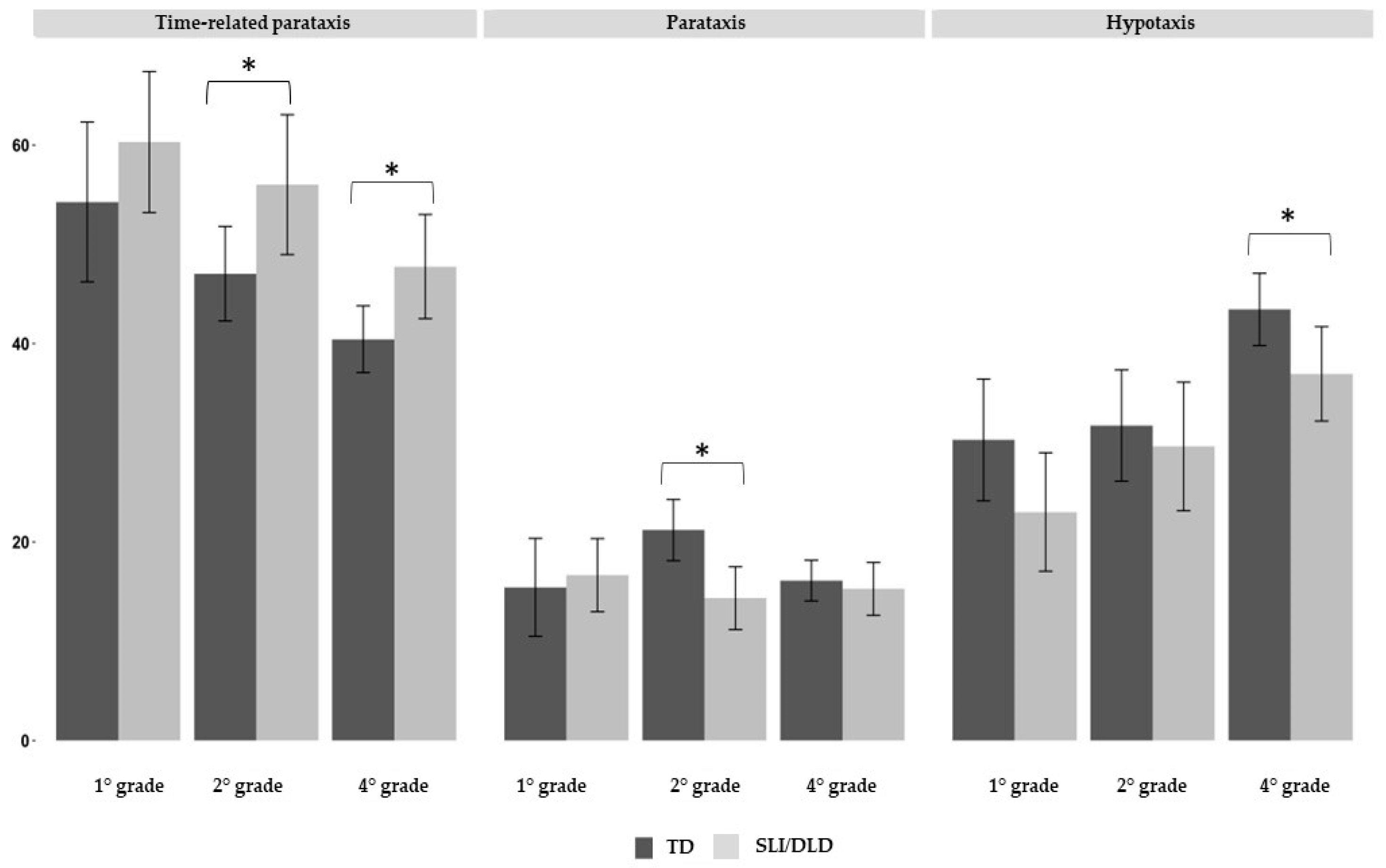

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Taxis | Group | TR parataxis* | Parataxis | Hypotaxis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1° grade | SLI/DLD | b | a | a |

| TD | c | a | b | |

| 2° grade | SLI/DLD | c | a | b |

| TD | c | a | b | |

| 4°grade | SLI/DLD | C | a | b |

| TD | B | a | b |

Appendix B

| Taxis | Group | 1° grade | 2° grade | 4°grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TR parataxis* | SLI/DLD | B | b | a |

| TD | B | ab | a | |

| Parataxis | SLI/DLD | A | a | a |

| TD | A | b | ab | |

| Hypotaxis | SLI/DLD | A | A | b |

| TD | A | A | b |

References

- Tomblin, B. Children with specific language impairment. In The Cambridge handbook of child language, 1st ed.; Bavin, E., Ed.; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, England, 2009; pp. 417–431. [Google Scholar]

- Andreu, L.; Ahufinger, N.; Igualada, A.; Sanz-Torrent, M. Descripción del cambio de TEL a TDL en contexto angloparlante. Rev Investig Logop. 2021, 11, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Botting, N. Specific language impairment. In Encyclopedia of language development, 1st ed.; Hoff, E., Shatz, M., Eds.; SAGE Publications: California, USA, 2014; pp. 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinis, T. On the nature and cause of specific language impairment: A view from sentence processing and infant research. Lingua 2011, 121, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auza, A. ¿Qué es el trastorno del lenguaje? Un acercamiento teórico y clínico a su definición. Lenguaje 2009, 37, 365–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedore, LM.; Leonard, LB. Specific language impairment and grammatical morphology: A discriminant function analysis. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 1998, 41, 1185–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, LB.; Miller, C.; Gerber, E. Grammatical morphology and the lexicon in children with specific language impairment. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 1999, 42, 678–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, LB. Specific Language Impairment, 1st ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza, E. Trastorno Específico del Lenguaje (TEL). Avances en el estudio de un trastorno invisible, 1st ed.; Pirámide: Madrid, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Conti-Ramsden, G. Processing and linguistic markers in young children with Specific Language Impairment (SLI). Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2008, 60, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson-Maldonado, D.; Maldonado, R. Grammaticality differences between Spanish-speaking children with specific language impairment and their typically developing peers. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2017, 52, 750–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, E.; Carballo, G.; Muñoz, J.; Fresneda, M.D. Evaluación de la comprensión gramatical: un estudio translingüístico. Rev Logop Foniatr Audiol. 2005, 25, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, V.M.; Axpe, Á.; Moreno, A.M. El estudio de la agramaticalidad en el discurso narrativo del trastorno específico del lenguaje. Onomázein 2014, 29, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buiza, JJ.; Adrián, JA.; González, M.; Rodríguez-Parra, MJ. Evaluación de marcadores psicolingüísticos en el diagnóstico de niños con trastorno específico del lenguaje. Rev. de Logop. Foniatr. y Audiol. 2004, 24, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, LB.; Wong, A.; Deevy, P.; Stokes, SF.; Fletcher, P. The production of passives by children with specific language impairment: Acquiring English or Cantonese. Appl Psychoinguist. 2006, 27, 267–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinellie, S.A. Complex syntax used by school-age children with Specific Language Impairment (SLI) in child-adult conversation. J Commun Disord. 2004, 37, 517–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A. La intervención en morfosintaxis desde un enfoque interactivo: un estudio de escolares con retraso de lenguaje. Rev. de Logop. Foniatr. y Audiol. 2003, 23, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuele, CM.; Tolbert, L. Omissions of obligatory relative markers in children with specific language impairment. Clin. Linguist. Phon. 2001, 15, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, M.; Serrat, E.; Solé, R.; Bel, A.; Aparici, M. La adquisición del lenguaje, 1st ed.; Ariel: Barcelona, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Schuele, CM.; Dykes, JC. Complex syntax acquisition: A longitudinal case study of a child with specific language impairment. Clin. Linguist. Phon. 2005, 19, 295–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hincapié, L.; Giraldo, M.; Lopera, F.; Pineda, D.; Castro, R.; Lopera, JP.; Mendieta, N.; Jaramillo, A.; Arboleda, A.; Aguirre, D.; Lopera, E. Trastorno Específico del Desarrollo del Lenguaje en una población infantil colombiana. Univ. Psychol. 2008, 7, 557–569. [Google Scholar]

- Buiza, J.; Rodríguez-Parra, MJ.; González-Sánchez, M.; Adrián, J. Specific language impairment: Evaluation and detection of differential psycholinguistic markers in phonology and morphosyntax in Spanish-speaking children. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 58, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auzá, A.; Chávez, A. ¿Qué me cuentas? Narraciones y desarrollo lingüístico en niños hispanohablantes, 1st ed.Auza, A., Hess, K., Eds.; Ediciones De Laurel: Monterrey, Mexico, 2013; pp. 59–84. [Google Scholar]

- Thordardottir, E. Language-specific effects of task demands on the manifestation of specific language impairment: A comparison of English and Icelandic. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2008, 51, 922–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coloma, CJ.; Araya, C.; Quezada, C.; Pavez, MM.; Maggiolo, M. Grammaticality and complexity of sentences in monolingual Spanish-speaking children with specific language impairment. Clin. Linguist. Phon. 2016, 30, 649–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro, P.; Crespo, N.; Alvarado, C. Complejidad sintáctica en narraciones de niños con desarrollo típico, trastorno específico del lenguaje y discapacidad intelectual. Sintagma: Rev. Ling. 2016, 28, 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Barako Arndt, K.; Schuele, CM. Production of infinitival complements by children with specific language impairment. Clin Linguist Phon. 2012, 26, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson-Maldonado, D.; Maldonado, R. La complejidad sintáctica en niños con y sin Trastorno Primario de Lenguaje. In Lingüística Funcional, 1st ed.; Rodríguez Sánchez, I., Vázquez, E., Eds.; Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro: Querétaro, México, 2015; pp. 253–301. [Google Scholar]

- Ferinú, L.; Ahufinger, N.; Pacheco-Vera, F.; Andreu, L.; Sanz-Torrent, M. Dificultades morfosintácticas en niños de 5 a 8 años con trastorno del desarrollo del lenguaje a través de subpruebas del CELF-4. Rev. Logop. Foniatr. Audiol. 2021, 41, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, C.; Windsor, J. General Language Performance Measures in Spoken and Written Narratives and Expository Discourse of School-Age Children with Language Learning Disabilities. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2000, 43, 324–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilla-Earls, AP.; Eriks-Brophy, A. Spontaneous language measures in monolingual preschool Spanish-speaking children. Rev. Logop. Foniatr. Audiol. 2012, 32, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, R.A. Desarrollo del lenguaje, 1st ed.; Octaedro: Barcelona, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Auzá, A.; Alarcón, L. Cláusulas subordinadas y coordinadas en dos tareas narrativas producidas por niños mexicanos de primero de primaria. In Proceedings of the XVI Congreso Internacional de la ALFAL Alcalá de Henares, 6-9 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez-Clellen, VF.; Hofstetter, R. Syntactic complexity in Spanish narratives: A developmental study. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 1994, 37, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coloma, CJ.; Peñaloza, C.; Fernández, R. Producción de oraciones complejas en niños de 8 y 10 años. RLA: Rev. Ling. Teor. Apl. 2007, 45, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavez, M.; Coloma, CJ.; Araya, C.; Maggiolo, M.; Peñaloza, C. Gramaticalidad y complejidad en narración y conversación en niños con trastorno específico del lenguaje. Rev. Logop. Foniatr. Audiol. 2015, 35, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coloma, CJ.; Araya, C.; Quezada, C.; Pavez, M.; Álvarez, C.; Maggiolo, M. Development of grammaticality and sentence complexity in monolingual Spanish-speaking children with specific language impairment: an exploratory study. Sintagma: Rev. Ling. 2019, 31, 87–101. [Google Scholar]

- Domsch, C.; Richels, C.; Saldana, M.; Coleman, C.; Wimberly, C.; Maxwell, L. Narrative skill and syntactic complexity in school-age children with and without late language emergence. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2012, 47, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, L. Children with Specific Language Impairment, 1st ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Law, J.; Tomblin, B.; Zhang, X. Characterizing the Growth Trajectories of Language-Impaired Children Between 7 and 11 Years of Age. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2008, 51, 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo Allende, N.; Alfaro-Faccio, P.; Góngora-Costa, B.; Alvarado, C.; Marfull-Villanueva, D. Perfil sintáctico de niños con y sin Trastornos del Desarrollo del Lenguaje: Un análisis descriptivo. Rev. Signos. 2020, 53, 619–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, ML. Growth models of developmental language disorders. In Developmental language disorders, 1st Ed.; Rice, ML., Ed.; Psychology Press: London, England, 2004; pp. 214–247. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R. A First Language: The Early Stages, 1st ed.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Checa, I. Madurez sintáctica y subordinación: los índices secundarios clausales. Interlingüística. 2003, 14, 191–206. [Google Scholar]

- Coloma, CJ.; Silva, M.; Palma, S.; Holtheuer, C. Reading Comprehension in Children with Specific Language Impairment: An Exploratory Study of Linguistic and Decoding Skills. Psykhe 2015, 24, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, M.; Smolik, F.; Perpich, D.; Thompson, T.; Rytting, N.; Blossom, M. Mean length of utterance levels in 6-month intervals for children 3 to 9 years with and without language impairments. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2010, 53, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.; Lynce, S.; Carvalho, S.; Cacela, M.; Mineiro, A. Extensão média do enunciado-palavras em crianças de 4 e 5 años com desenvolvimento típico da linguagem. Rev CEFAC. 2015, 17, 1143–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon-Cereijido, G.; Gutierrez-Clellen, VF. Spontaneous language markers of Spanish language impairment. Appl Psycholinguist. 2007, 28, 317–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedore, LM.; Pena, ED.; Gillam, RB.; Ho, TH. Language sample measures and language ability in Spanish-English bilingual kindergarteners. J Commun Disord. 2010, 43, 498–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, K.W. Grammatical Structures Written at Three Grade Levels. NCTE Res Rep 1965, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, KW. Recent measures in syntactic development. Elem Engl. 1966, 43, 732–739. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, M.A.K.; Matthiessen, C.M. Introduction to Functional Grammar, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Eggins, S. Introduction to Systemic Functional Linguistics, 1st ed.; Ayc Black: London, England, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, MAK. ; Webster, J. The Language of Early Childhood, 1st ed.; Bloomsbury: London, England, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, G. Introducing Functional Grammar, 1st ed.; Arnold: London, England, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Educación. Decreto Supremo, 170/2010, Ley 20201, Unidad de Educación Especial. 2010.

- Pavez, MM. Test Exploratorio de Gramática Española de A. Toronto. Aplicación en Chile, 1st ed.; Ediciones UC: Santiago de Chile, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, R.; Souto, S. The use of articles by monolingual Puerto Rican Spanish-speaking children with specific language impairment. Appl Psycholinguist. 2005, 26, 621–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedore, LM.; Leonard, LB. Verb inflections and noun phase morphology in the spontaneous speech of Spanish-speaking children with specific language impairment. Appl Psycholinguist. 2005, 26, 195–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, G.; Restrepo, A.; Auza, A. Comparison of Spanish morphology in monolingual and Spanish–English bilingual children with and without language impairment. Biling Lang Cogn. 2013, 16, 578–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raven, J. Test de Matrices Progresivas. Escala Coloreada, General y Avanzada, 1st ed.; Paidós: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, G.; Flaxman, S.; Brunskill, E.; Mascarenhas, M.; Mathers, CD.; Finucane, M.; et al. Global and regional hearing impairment prevalence: an analysis of 42 studies in 29 countries. Eur J Public Health. 2013, 23, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavez, MM. , Coloma, CJ., Maggiolo, M. El Desarrollo narrativo en niños. Una propuesta práctica para la evaluación y la intervención en niños con trastorno del lenguaje, 1st ed.; Ars Médica: Barcelona, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson-Maldonado, D. La identificación del Trastorno Específico de Lenguaje en Niño Hispanohablantes por medio de Pruebas Formales e Informales. Rev Neuropsicol Neuropsiquiatr Neurocienc. 2011, 11, 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis, 1st ed.; Springer-Verlag: New York, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Gili Gaya, S. Estudios del Lenguaje Infantil, 1st ed.; Bibliograph, SA: Barcelona, Spain, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- van der Lely, HK.; Marshall, CR. Grammatical-specific language impairment: A window onto domain specificity. In The handbook of psycholinguistics and cognitive processes: Perspectives in communication disorders, 1st Ed.; Gouendouzi, J., Loncke, F., Williams, MJ., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, USA. 2011; pp. 401–418. [Google Scholar]

- Alarcón, L.; Auzá, A. Uso y función de nexos en la subordinación y coordinación. Evidencia de dos tareas narrativas de niños mexicanos de primero de primaria. Estudios de Lingüística Funcional 2015, 5, 23–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, DV.; Snowling, MJ.; Thompson, PA.; Greenhalgh, T.; Adams, C.; Archibald, L.; Baird, G.; Bauer, A.; Bellair, J.; Boyle, C.; Catalise-2 Consortium. Phase 2 of CATALISE: A multinational and multidisciplinary Delphi consensus study of problems with language development: Terminology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2017, 58, 1068–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, KB.; Schuele, CM. Multiclausal utterances aren't just for big kids: A framework for analysis of complex syntax production in spoken language of preschool-and early school-age children. Top Lang Disord. 2013, 33, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwitserlood, R.; van Weerdenburg, M.; Verhoeven, L.; Wijnen, F. Development of morphosyntactic accuracy and grammatical complexity in Dutch school-age children with SLI. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2015, 58, 891–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M. L. El estudio de la sintaxis infantil a partir del diálogo con niños: Aportes metodológicos. Interdisciplinaria 2010, 27, 277–296. [Google Scholar]

- Schleppegrell, MJ. The language of schooling: A functional linguistics perspective, 1st Ed. ed; Routledge: New York, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Moss, G. Textbook language, teacher mediation, classroom interaction and learning processes: The case of natural and social science textbooks in Barranquilla, Colombia. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Systemic Functional Congress. San Paulo: Brazil. 10 – 15 July 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, MAK. Towards a language-based theory of learning. Linguist Educ. 1993, 5, 9–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, D. Towards a reading-based theory of teaching. Proceedings of 33rd International Systemic Functional Congress.

| Instruments | Normal | At Risk | Deficit |

|---|---|---|---|

| STSG (expressive)* | > 36 | 26 - 36 | < 26 |

| STSG (receptive) | > 41 | 38 - 41 | < 35 |

| Raven | > 15 | ||

| Audiometry test | < 20 dB |

| Grade | Taxis | Group | Measure | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1° Grade | TR parataxis* | SLI/DLD | 54,27 | 19,07 |

| TD | 60,3 | 16,82 | ||

| Parataxis | SLI/DLD | 15,44 | 11,68 | |

| TD | 16,67 | 8,72 | ||

| Hypotaxis | SLI/DLD | 30,29 | 14,52 | |

| TD | 23,03 | 14,13 | ||

| 2° Grade | TR parataxis | SLI/DLD | 47,04 | 11,27 |

| TD | 56,01 | 16,68 | ||

| Parataxis | SLI/DLD | 21,21 | 7,3 | |

| TD | 14,35 | 7,5 | ||

| Hypotaxis | SLI/DLD | 31,75 | 13,29 | |

| TD | 29,64 | 15,34 | ||

| 4° Grade | TR parataxis | SLI/DLD | 40,44 | 7,96 |

| TD | 47,76 | 12,43 | ||

| Parataxis | SLI/DLD | 16,12 | 4,85 | |

| TD | 15,29 | 6,31 | ||

| Hypotaxis | SLI/DLD | 43,44 | 8,62 | |

| TD | 36,95 | 11,26 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).