Submitted:

08 June 2023

Posted:

08 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

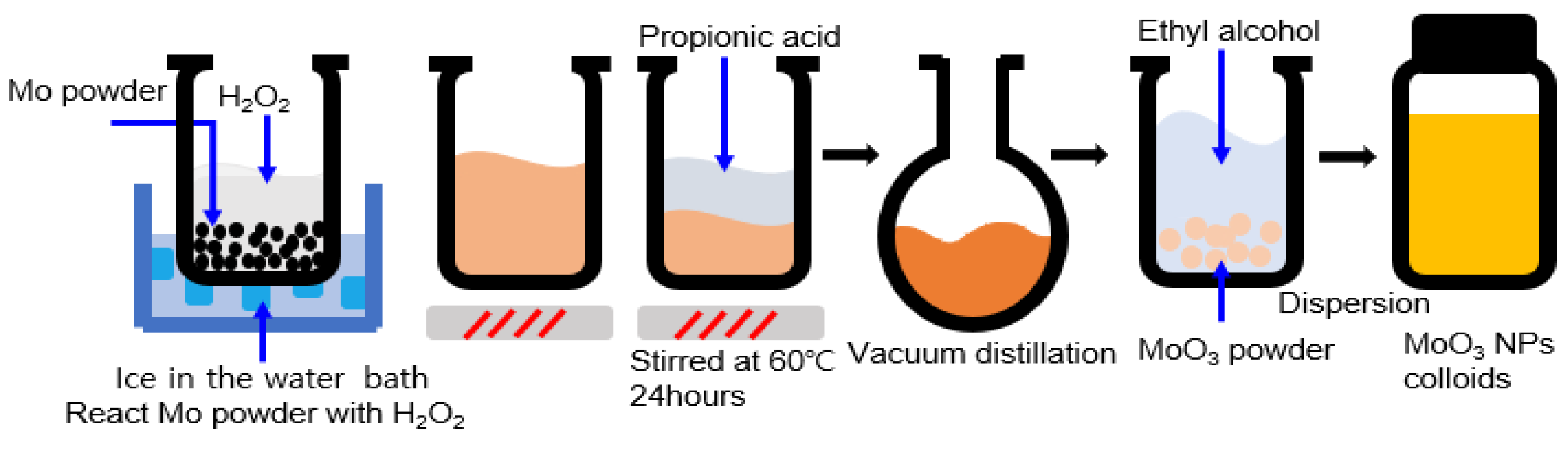

2.1. Synthesis of Materials

2.2. Device Fabrication

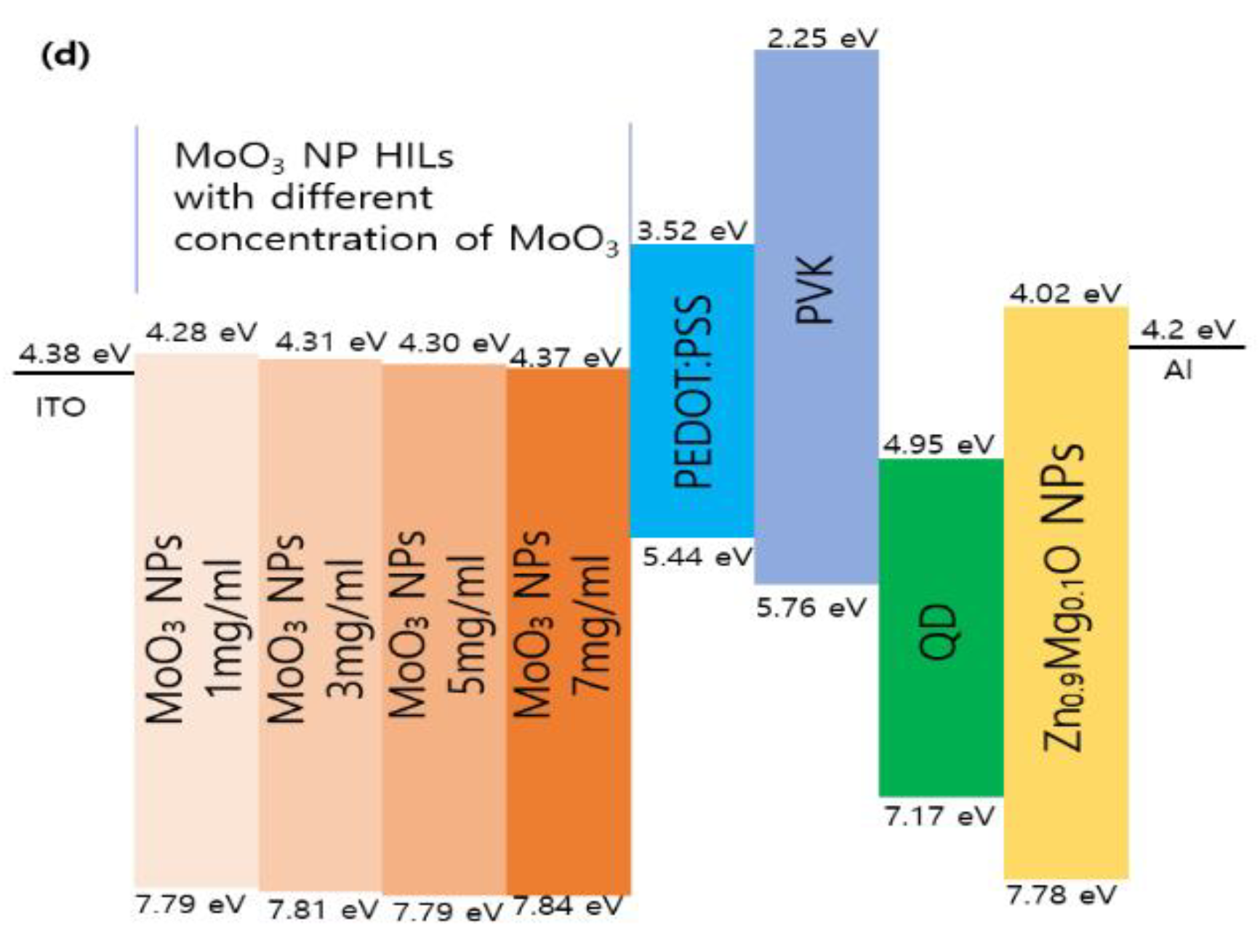

- A solution of MoO3 NPs was spin-coated onto the ITO substrate at a speed of 2000 rpm for 20 s at room temperature.

- Poly(N-vinyl-carbazole) (PVK) (Sigma Aldrich) was dissolved at a concentration of 1.2 wt%. The PVK solution was then spin-coated onto the patterned ITO glass substrate. The spin-coating process consisted of spinning at 600 rpm for 5 s, followed by spinning at 1500 rpm for 15 s, both at room temperature.

- CdSe/ZnS QDs (Zeus) were dissolved in heptane at a concentration of 5 mg/mL to create the EML. The QD solution was spin-coated onto the ITO/PVK substrate at a speed of 3000 rpm for 5 s at room temperature.

- A solution of Zn0.9Mg0.1O NPs was spin-coated onto the ITO/MoO3/PVK/QD substrate at a speed of 2000 rpm for 20 s at room temperature.

2.3. Characterizations

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Colin, V.L.; Schlamp, M.C.; Alivisators, A.P., Light-Emitting Diodes Made from Cadmium Selenide Nanocrystals and a Semiconducting Polymers. Nature, 1994, 370, 354–357. [CrossRef]

- Wood, V.; Bulović, V., Colloidal Quantum Dot Light-Emitting Devices, Nano. Rev. 2010, 1, 5202. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M. Lee; Shin, D,; Cho, N.-K.; Yi, Y.; Kang, S. J., A Solution-Processable Inorganic Hole Injection Layer that Improves the Performance of Quantum-Dot Light-Emitting Diodes, Curr. Appl. Phys. 2017, 17, 442-447.

- . [CrossRef]

- Bae, W. K.; Lim, J.; Lee, D.; Park, M.; Lee, H.; Kwak, J.; Char, K.: Lee, C.; Lee, S., R/G/B Natural White Light Thin Colloidal Quantum Dot-Based Light-Emitting Devices, Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 6387-6393. [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Chen, J.; Zhao, D.; Huang, Q.; Khan, Q.; Liu, X.; Tao, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Lei, W., Surface Plasmon-enhanced Quantum Dot Light-emitting Diodes by Incorporating Gold Nanoparticles, Opt. Express, 2016, 24, A33–A43.

- . [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z. W.; Han, D. B.; Tang, J. L.; Bai, Z. L.; Zhong, H. Z., Alcohol-Soluble Quantum Dots: Enhanced Solution Processability and Charge Injection for Electroluminescence Devices, IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron., 2017, 23, 1900708. [CrossRef]

- Caruge, J. M.; Halpert, J. E.; Wood, V.; Bulovic, V.; Bawendi, M. G., Colloidal Quantum-Dot Light-Emitting Diodes with Metal-Oxide Charge Transport layers, Nature Photonic. 2008, 2, 247-250. [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Zheng, Y.; Xue, J.; Holloway, P. H., Stable and Efficient Quantum-Dot Light-Emitting Diodes Based on Solution-Processed Multilayer Structures, Nature Photonics, 2011, 5, 543-548. [CrossRef]

- Shirasaki, Y.; Supran, G. J.; Bawendi, M. G.; Bulović, V., Emergence of Colloidal Quantum-Dot Light-Emitting Technologies, Nature Photon. 2013, 7, 13– 23. [CrossRef]

- Mashford, B. S.; Stevenson, M.; Popovic, Z.; Hamilton, C.; Zhou, Z.; Breen, C.; Steckel, J.; Bulović, V.; Bawendi, M.; Coe-Sullivan, S.; Kazlas, P. T., High-Efficiency Quantum-Dot Light-Emitting Devices with Enhanced Charge Injection, Nat. Photon. 2013, 7, 407-412. [CrossRef]

- Rhee, S.; Kim, K.; Roh, J.; Kwak, J., Recent Progress in High-Luminance Quantum Dot Light-Emitting Diodes, Curr. Opt. Photon. 2020, 4, 161-173. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., Ye, Y.; Pu, C.; Deng, Y.; Dai, X.; Chen, X.; Chen, D.; Zheng, X.; Gao, Y.; Fang, W.; Peng, X.; Jin, Y., High-Performance, Solution-Processed, and Insulating-Layer Free Light-Emitting Diodes Based on Colloidal Quantum dots, Adv. Mater. 2018, 1801387. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hou, X.; Dai, X.; Yao, Z.; Lv, L.; Jin, Y.; Peng, X., Stoichiometry-Controlled InP-Based Quantum Dots: Synthesis, Photoluminescence, and Electroluminescence, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 6448-6452. [CrossRef]

- Kwak, J; Bae, W. K.; Lee, D.; Park, I.; Lim, J.; Park, M.; Cho, H.; Woo, H.; Yoon, D. Y.; Char, K.; Lee, S.; Lee, C., Bright and Efficient Full-Color Colloidal Quantum Dot Light-Emitting Diodes Using an Inverted Device Structure, Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 2362-2366. [CrossRef]

- Son, D. I.; Kwon, B. W.; Park, D. H.; Seo, W. S.; Yi, Y.; Angadi, B.; Lee, C. L.; Choi, W. K., Emissive ZnO-Graphene Quantum Dots for White-Light-Emitting Diodes, Nat. Nanotechnol. 2012, 7, 465. [CrossRef]

- Haung, J.; Miller, P. F.; Wilson, J. S.; de Mello, J. C.; Bradly, D. D. C., Investigation of the Effects of Doping and Post-Deposition Treatments on the Conductivity, Morphology, and Work Function of Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)/Poly(styrene sulfonate) Films, Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015, 15, 290-296. [CrossRef]

- Murase, S., Yang, Y., Solution Processed MoO3 Interfacial Layer for Organic Photovoltaics Prepared by a Facile Synthesis Method, Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 2459-2462. [CrossRef]

- Jasieniak, J. J.; Seifter, J.; Jo, J.; Mates, T.; Heeger, J., A Solution-Processed MoOx Anode Interlayer for Use within Organic Photovoltaic Devices, Adv. Func. Mater. 2012, 22, 2594-2605. [CrossRef]

- de Jong, M. P.; van Ijzendoorn, L. J.; de Voigt, M. J. A., Stability of the Interface between Indium-Tin-Oxide and Poly(3,4-Ethylenedioxythiophene)/Poly(Styrenesulfonate) in Polymer Light-Emitting Diodes, Appl. Phys. Lett. 2000, 77, 2255-2257. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Mutlugun, E.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, Y.; Leck, K. S.; Ma, Y.; Ke, L.; Tan, S. T.; Dimir, H. V.; Sun, X. W., Solution Processed Tungsten Oxide Interfacial Layer for Efficient Hole-Injection in Quantum Dot Light-Emitting Diodes, Small, 2014, 10, 247-252. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Qu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Xiong, J.; Cai, P.; Xue, X.; Liu, L.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X., Facile Solution-Processed Aqueous MoOx for Feasible Application in Organic Light-Emitting Diode, Opt. Laser Technol. 2018, 101, 85-90. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, B.; Park, M.; Kwon, Y.; An, M.; Shin, D.; Jeon, J.; Kim, J.; Lee, W.; Lim, J.; Lee, D., Hole Injection of Quantum Dot Light-Emitting Diodes Facilitated by Multilayered Hole Transport Layer, Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 558, 149944. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-S.; Yang, S.-H.; Tseng, W.-C.; Chen, W.; Lu, Y.-C., Utilization of Nanoporous Nickel Oxide as the Hole Injection Layer for Quantum Dot Light-Emitting Diodes, ACS Omega, 2021, 6, 13447-13455. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, Y.; Ki, J., Solution-Processed NiO as a Hole Injection Layer for Stable Quantum Dot Light-Emitting Diodes, Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4422. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Dai, X.; Liang, X.; Chen, D.; Zheng, X.; Li, Y.; Deng, Y.; Du, H.; Ye, Y.; Chen, D.; Lin, C.; Ma, L.; Bao, Q.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L., High-Performance Quantum-Dot Light-Emitting Diodes Using NiOx Hole-Injection Layers with a High and Stable Work Function, Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1907265. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, D.; Kim, B.; Hwang, B.; Kim, C., Improved Performance of Quantum Dot Light-Emitting Diodes by Introducing WO3 Hole Injection Layers, Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 2021, 735, 51-60. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, S.; Li, D.; Fang, Y.; H. Shen; L. Li; Z Du, Simultaneous Improvement of Efficiency and Lifetime of Quantum Dot Light-Emitting Diodes with a Bilayer Hole Injection Layer Consisting of PEDOT:PSS and Solution-Processed WO3, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2018, 10, 24232. [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Sang, D.; Zou, L.; Wang, Q.; Liu, C., A Review on the Properties and Applications of WO3 Nanostructure-Based Optical and Electronic Devices, Nanomater. 2021, 11, 2136. [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Seok, H.; Rhee, S.; Hahm, D.; Bae, W.; Kim, H., Magnetron-Sputtered Amorphous V2O5 Hole Injection Layer for High Performance Quantum Dot Light-Emitting Diode, J. Alloy. Compound. 2021, 878, 160303. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Xu, K.; Zheng, Q.; Xu, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Liu, L., Aqueous Solution-Processed Vanadium Oxide for Efficient Hole Injection Interfacial Layer in Organic Light-Emitting Diode, Phys. Status Solidi A, 2018, 215, 1800047. [CrossRef]

- Heo, S.; Yu, J.; Kim, M.; Yi, Y.; Lee, J.; Kim, H., Interfacial Electronic Structure between a W-doped In2O3 Transparent Electrode and a V2O5 Hole Injection Layer for Inorganic Quantum-Dot Light-Emitting Diodes, RSC Advances, 2019, 9, 11996-12000. [CrossRef]

- Matsushima, T.; Kinoshita, Y.; Murata, H., Formation of Ohmic Hole Injection by Inserting an Ultrathin Layer of Molybdenum Trioxide between Indium Tin Oxide and Organic Hole-Transporting Layers, Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 91, 253504. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.; Shu, A.; Kröger, M.; Kahn, A., Effect of Contamination on the Electronic Structure and Hole-Injection Properties of MoO3/Organic Semiconductor Interfaces, Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010, 96, 133308. [CrossRef]

- You, H.; Dai, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, D., Improved Performances of Organic Light-Emitting Didoes with Metal Oxide as Anode Buffer, J. Appl. Phys. 2007, 101, 026105. [CrossRef]

- Matsushima, T.; Jin, G.-H.; Murata, H., Marked Improvement in Electroluminescence Characteristics of Organic Light-Emitting Diodes Using an Ultrathin Hole-Injection Layer of Molybdenum Oxide, J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 104, 054501. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; You, F.; Zheng, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Ping, Z.; Cai, P.; Xue, X.; Xiong, J.; Zhang, J., Solution-Processed MoOx Hole Injection Layer Toward Efficient Organic Light-Emitting Diode, Org. Electron. 2016, 39, 43-49. [CrossRef]

- Eun, Y.; Jang, G.; Yang, J.; Kim, S.; Chae, Y.; Ha, M.; Moon, D.; Kim, C., Performance Improvement of Quantum Dot Light-Emitting Diodes Using a ZnMgO Electron Transport Layer with a Core/Shell Structure, Mater. 2023, 16, 600. [CrossRef]

- Alwan, R. M.; Kadhim, Q. A.; Sahan, K. M.; Ali, R., A.; Mahdi, R. J.; Kassim, N. A.; Jassim, A. N., Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles via Sol-Gel Route and Their Characterization, NanoSci. Nanotechnol. 2015, 5(1), 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Viezbicke, B.; Patel, S.; Davis, B.; Birnie, D., Evaluation of the Tauc Method for Optical Absorption Edge Determination: ZnO Thin Films as a Model System, Phys. Status Solidi Basic, 2015, 252, 1700–1710. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, J.; Park, J.; Shin, E.; Roh, Y., Improving Hole Injection Ability Using a Newly Proposed WO3/NiOx Bilayer in Solution Processed Quantum Dot Light-Emitting Diodes, Curr. Appl. Phys. 2022, 38, 81-90. [CrossRef]

- Wood, V.; Panzer, M.; Caruge, J.; Halpert, J.; Bawendi, M.; Bulovic, V., Air-Stable Operation of Transparent, Colloidal Quantum Dot Based LEDs with a Unipolar Device Architecture, Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 24-29. [CrossRef]

- Veijo, J.; Jensen, K.; Mattoussi, H.; Michel, J.; Dabbousi, B.; Bawendi, M., Cathodoluminescence and Photoluminescence of Highly Luminescence CdSe/ZnS Quantum Dot Composite, Appl. Phys. Lett. 1997, 70, 2132-2134. [CrossRef]

- Empedocles, S.; Bawendi, M., Quantum-Confined Stark Effect in Single CdSe Nanocrystallite Quantum Dots, Science, 1997, 278, 2114-2117. [CrossRef]

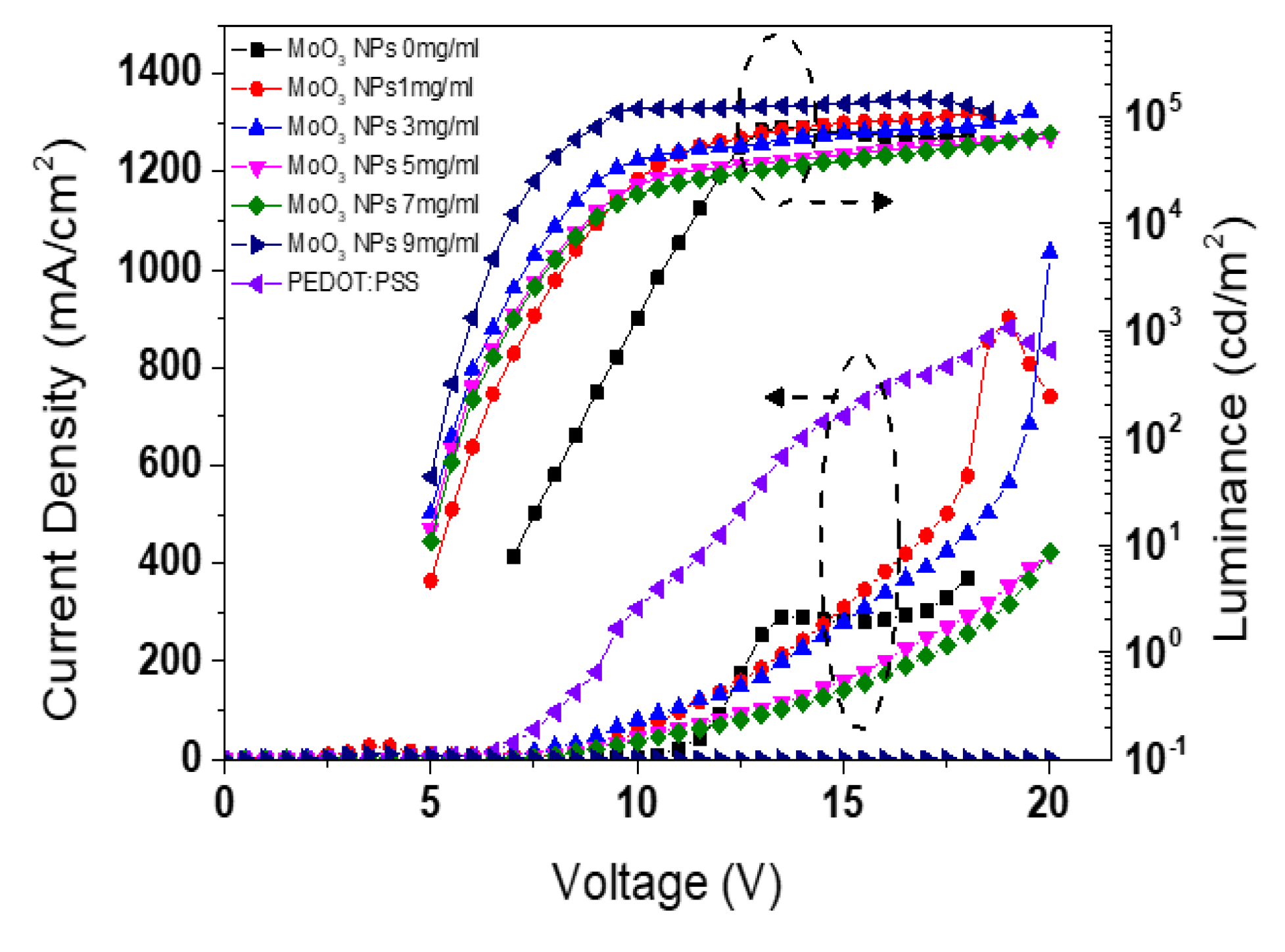

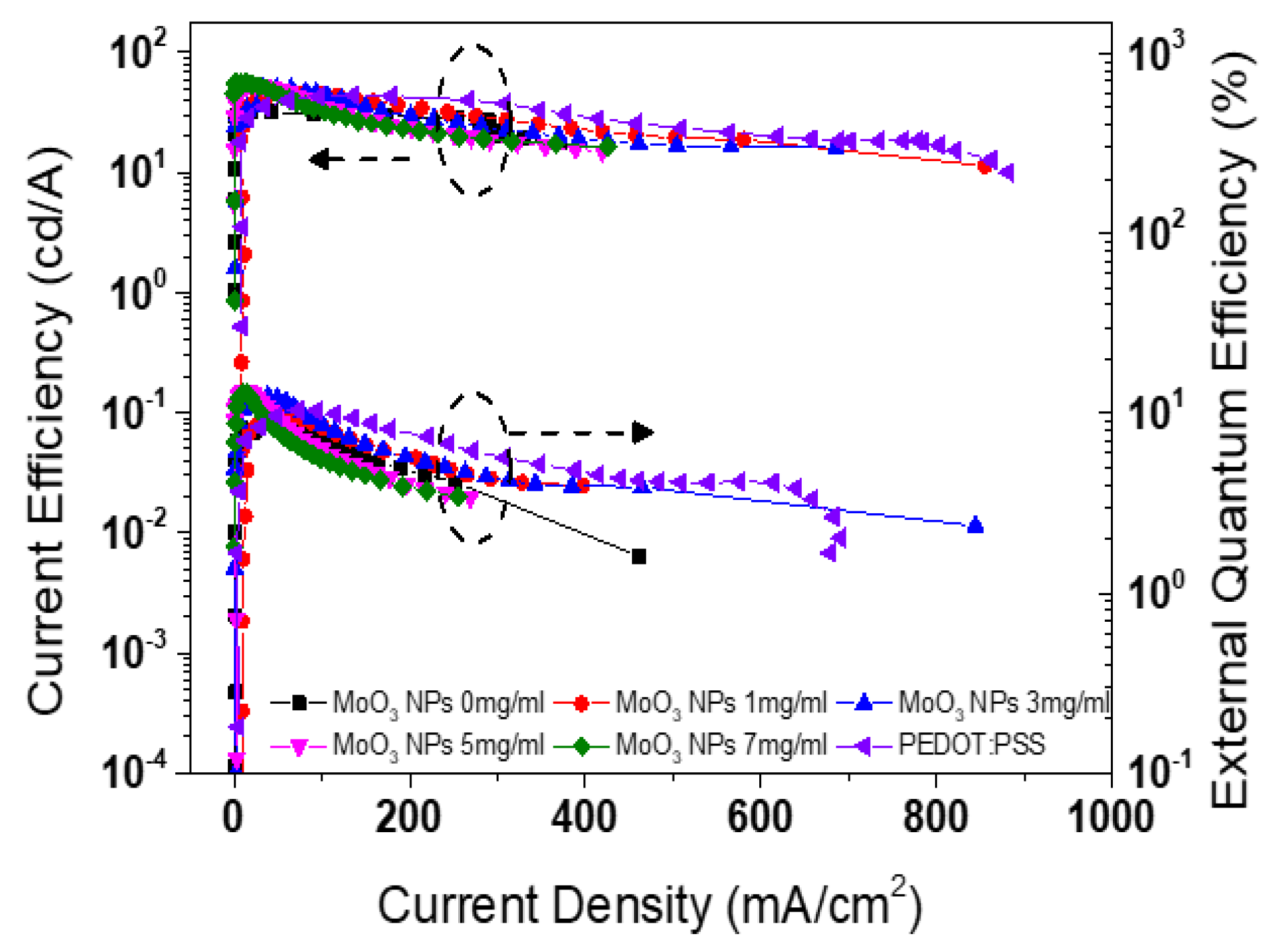

| Types of HIL | Current density at 16 V (mA/cm2) | Maximum luminance (cd/m2) |

Maximum luminous efficiency (cd/A) | Maximum EQE (%) |

| PEDOT:PSS MoO3 NPs of 0 mg/ml |

761.2 285.2 |

143,510.7 71,993.7 |

44.3 35.1 |

11.0 9.25 |

| MoO3 NPs of 1 mg/ml | 384.0 | 109,013.4 | 45.5 | 10.3 |

| MoO3 NPs of 3 mg/ml | 339.7 | 111,781.8 | 50.4 | 12.5 |

| MoO3 NPs of 5 mg/ml | 202.5 | 63,334.8 | 53.9 | 12.9 |

| MoO3 NPs of 7 mg/ml | 173.7 | 69,240.7 | 56.0 | 13.2 |

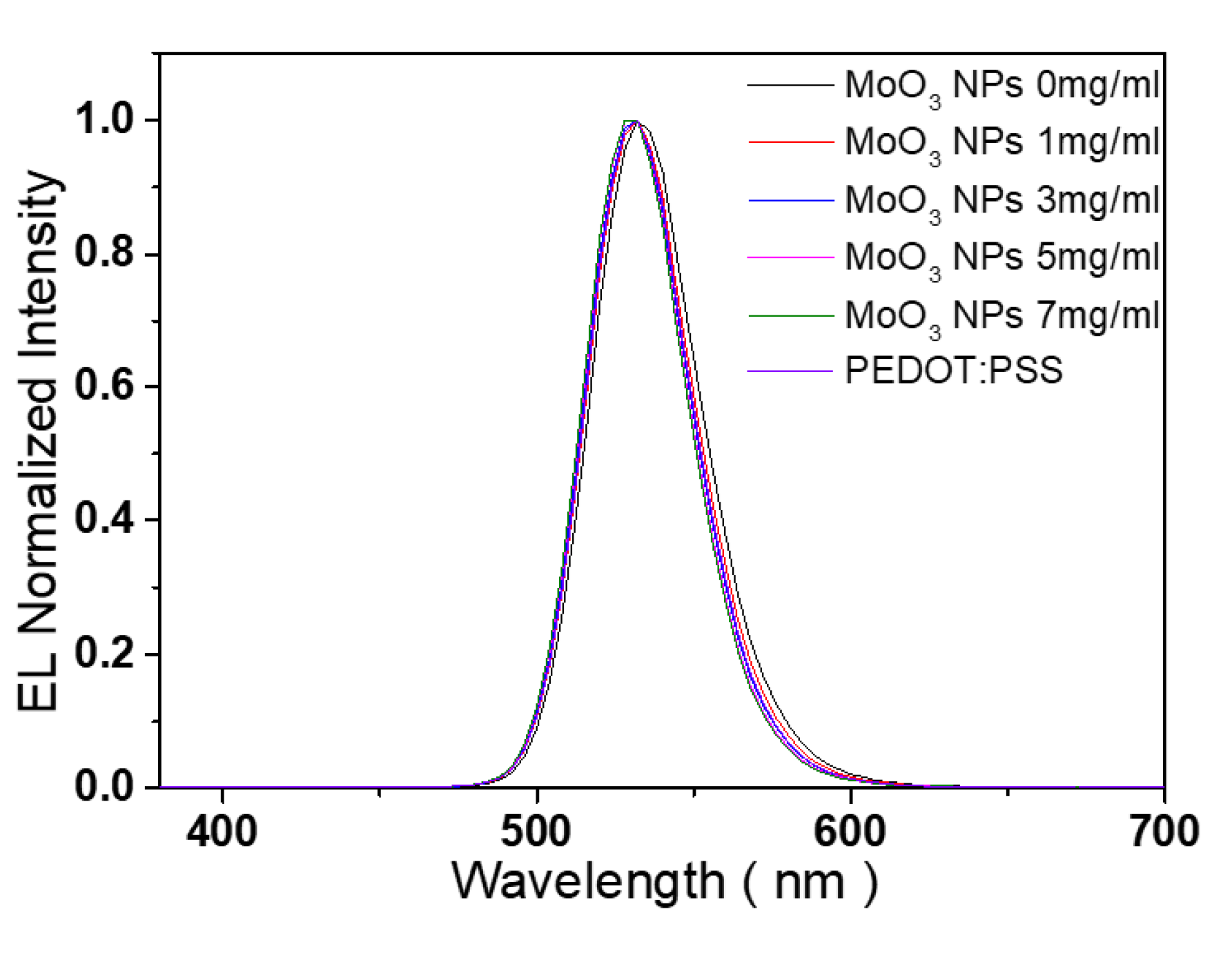

| sample | Peak (nm) | FWHM (nm) |

| PL of QD | 544 | 33.3 |

| EL of QLED with 0 mg/ml MoO3 NP HIL |

532 | 41.0 |

| EL of QLED with 1 mg/ml MoO3 NP HIL |

532 | 35.9 |

| EL of QLED with 3 mg/ml MoO3 NP HIL |

532 | 36.0 |

| EL of QLED with 5 mg/ml MoO3 NP HIL |

532 | 36.6 |

| EL of QLED with 7 mg/ml MoO3 NP HIL |

532 | 37.2 |

| EL of QLED with PEDOT:PSS HIL | 532 | 39.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).