1. Introduction

Despite numerous nutrition intervention, programs that have been implemented over the previous four decades, undernutrition is still an important health issue in India (Meshram, I.I. et al., 2018).In demographics view, this Adivasis, or tribal communities, account for 8.6% of India's population (Xaxa, V., 2014). According to the 2011 Census, the tribal community in West Bengal accounts for around 5.8% of the overall population of the state. West Bengal's tribal population accounts for around 5.08% of the country's overall tribal population (Tribal Development Department, Govt. of West Bengal). It seems that, among tribal children they have higher amounts of undernourishment than children from more wealthy backgrounds; according to the CNNS 2016-18 study, over 40% of under-five indigenous children in India are stunted (Tribal Nutrition, UNICEF, India). From recent report, it’s found that, India ranks 107th out of 121 nations in the global hunger index, which measures child nutritional deficiencies, stunting, wasting, and child mortality (India Global Hunger Index, 2022). Also others, reported in the Registrar General of India's (RGI) Sample Registration System (SRS) Report, West Bengal's Infant Mortality Rate (IMR) in 2019 is 20 children per one thousand live births, which is more compared to numerous other states (Press Information Bureau, 2022).From these its clear that, India's indigenous societies continue to be the most nutrient socially deprived communities in the nation; they traditionally lead diverse lifestyles and their standard of living is indigenous; they are also more vulnerable to poor nutrition, which is identified as a predominant health issue, primarily due to underutilization of different governmental facilities, that has serious and long effects for the child's well-being and negatively influences the development of the country. Primitive kids have a higher probability to be malnourished at a young age because of the lack of parental information about the necessity of breast feeding, adequate nutritional food intake, vaccination, care during illness, safe drinking water, hygienic practices, and so on (Dey, U. and Bisai, S., 2019).

Moreover, tribal inhabitants are unable to get sufficient healthcare services because of poverty, limited access, and maximum service costs, as well as high out-of-pocket expenses in health and nutrition, which results in impoverishment and indebtedness, ultimately that leads to suffer from disease and micronutrient deficiencies (Babu, B.V. and Kusuma, Y.S., 2007). Most notably, widespread undernourishment is substantially associated with and unquestionably directly connected to high infant mortality (Black, R.E. et al., 2008). There is almost no part or dimension of existence that does not have one or more of these characteristics. Even children were not able to escape the all-encompassing impact of such characteristics. Tribal groups are among the most marginalized and underprivileged groups in Indian society. Despite the fact that many policies and practices have been sought and implemented for their social as well as economic betterment in post-Independence India, all development initiatives reveal them to be the most marginalized from mainstream Indian society (Xaxa, V., 2011). The nutritional concerns of tribal societies are fraught with ambiguity, and relatively few extensive research on the populations' food habits and nutritional health are available (Ahmad Khanday, Z. and Akram, M., 2012).

In this regard, researchers used the WHO criteria for undernutrition prevalence as underweight, stunting, and wasting by percentage prevalence of these three indicators between children to assess the total nutritional stress and severity of undernutrition among tribal children (World Health Organization, 1995). To recover from this undernutrition status, the is a need to strengthen the children's nutritional condition in the nation, where, mothers must be sufficiently educated about feeding procedures as well as the importance of following appropriate sanitation and good hygiene practises. Additionally, special care must be paid to all of these indigenous tribes, with much more policy measures and initiative, as these people are frequently cut-off from mainstream of society and may be unaware of, so they cannot benefit from, the different schemes that are provided (Padmanabhan, P.S. and Mukherjee, K., 2016). So, for this, the intent of this paper is to explore and comprehend the factors affecting the nutritional status of tribal children in West Bengal.

2. Objectives

To analyze the effect of household, child, and maternal characteristics on actual children under the age of five.

The study's objective is to figure out the relationship between some specified factors and the nutritional status of scheduled tribal children.

3. Hypotheses

Maternal characteristics and the socioeconomic status of the family, as well as sanitation, have an impact on their child's nutritional health.

Moreover, the children's characteristics impact their anthropometrics and stagnant their entire cognitive development.

4. Study Area

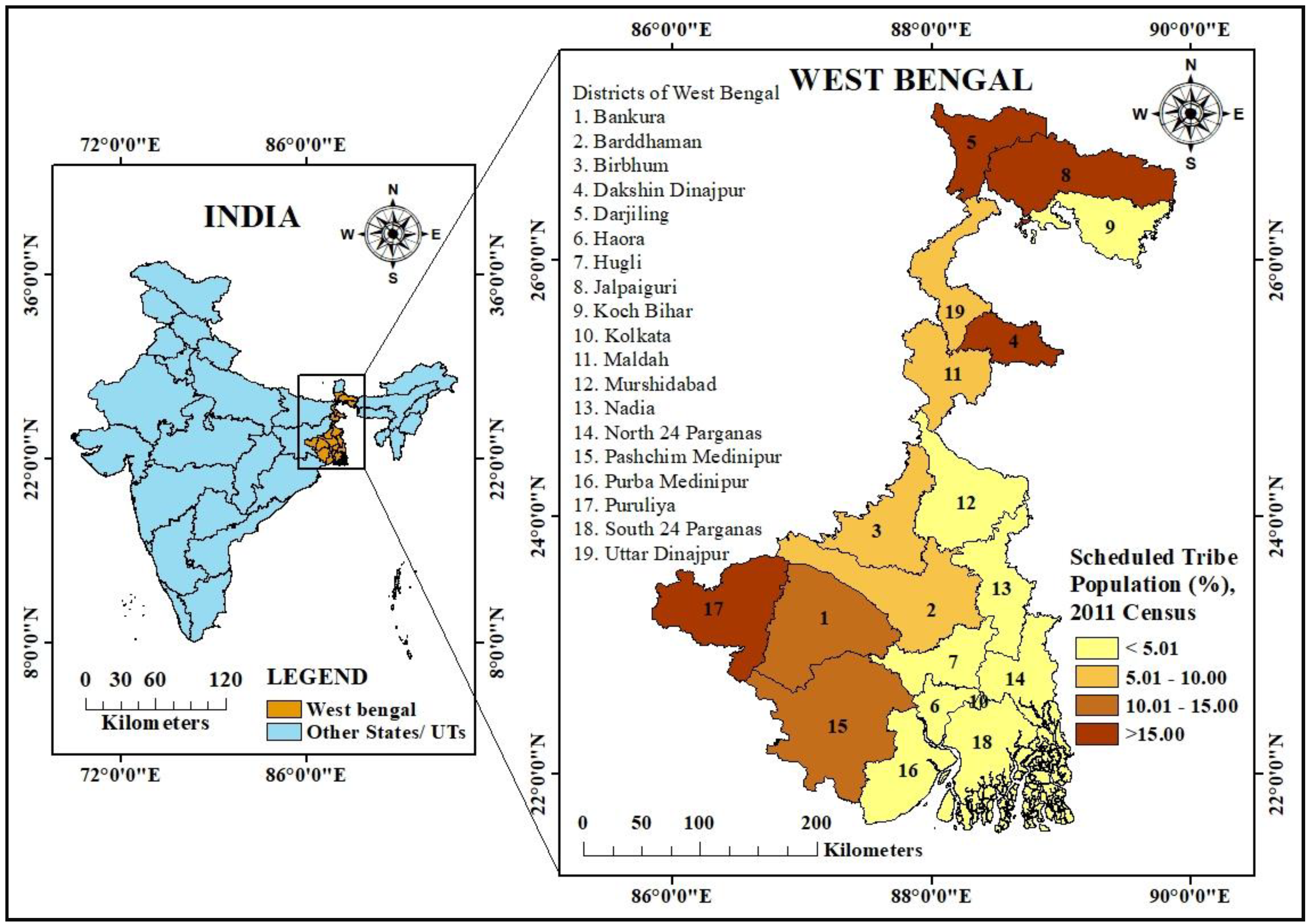

According to the 2011 Indian Census, there are total 19 districts in West Bengal with more than 5.2 million tribal people, representing for around 5.8% of the state's overall population. Tribal populations may be found in every district in the state. But some of the districts with a higher proportion of tribal people include Darjeeling, Jalpaiguri, Puruliya, Dakshin Dinajpur, Bankura, and Pashchim Medinipur. As Per NFHS-5 (2019-20) in West Bengal, Neonatal Mortality Rate (NNMR) found 15.5, Infant Mortality rate (IMR) 22.0, Under five Mortality Rate (U5MR) 25.4, counted as per 1000 live birth, which is still higher than the many other states of India.

Figure 1.

Location map of the study area, West Bengal, India.

Figure 1.

Location map of the study area, West Bengal, India.

5. Materials & Methods

5.1. Source of Data

In this study, “PR” file (People datasets) and “KR” file (Children under five of interviewed women file datasets) of NFHS-IV (2015-16) & NFHS-V (2019-20) is taken to assess the nutritional conditions of children (U5 age), their biological mother and their household characteristics datasets were taken from the Demographic Health Survey site (

https://dhsprogram.com/data/dataset_admin/index.cfm) of NFHS-IV & V, and this is regulated by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, and the International Institute of Population Sciences (IIPS) serves as a nodal agency for this survey.

5.2. Measurement of Children Nutritional Status

Three anthropometric indicators were utilized for tracking undernutrition of ST children to evaluate nutritional health: stunting (low height-for-age); underweight (low weight-for-age); and wasting (low weight-for height). Where the, Underweight is the combination of stunting and wasting among all these three indices, and this study examined stunting, wasting, and underweight. All of the parameters applied in this study were established by the WHO (2006) child growth guidelines (

Table 1).

5.3. Variables

There are many associated factors that determines the children nutritional status which leads thir anthropometrical development status. For this among under 5 age ST children nutritional status, some selected determinant factors are taken as mothers characteristics (mothers age, mother’s educational status, mothers anemia status, children under currently breastfeeding), children characteristics ( child age, children’s sex, birth order of children according to birth history, size of children during their birth) and household characteristics (type of place of residence, drinking water facility, toilet facility, types of cooking fuel).

5.4. Data Analysis

Data analysis was carried out using SPSS (26.0 Version) software. Where, Chi-square (

) test, bivariate analysis was done to study association between ST children’s (under 0-59 months age) undernutrition status by three anthropometrical indicies as dependent variable with the mothers, children, household characteristics as independent variable to find out the prevalence and association between those variables of undernutrition of two rounds of NFHS data. To prepare the mean of standardized Z-Score by 3 months age group (by line graph) of under 5year age Scheduled Tribe children, here Ms-excel is used.

where,

, is the observed frequency count for ith level of the categorical variable

, is the expected frequency count for ith level of the categorical variable.

6. Result & Discussions

The study counts scheduled tribe children 357 for NFHS-IV & 292 for NFHS-V (

Table 2). In NFHS-IV it’s found that 38.9 % children were stunted, 29.4% wasted and 42.9% underweight. Out of total children’s mother, majority of the mothers (38.4%) age ranges from 20-24 year. Educational level of mother is very low (1.1%) in higher education as its high (42.5%) in secondary education, also no education is not at a negligible point (36.7%). There was 80.6% of child’s mother found anemic. 83.8% children found under Currently breastfeeding. Highest number of children (24.4%) found at their antenatal stage. Nearly half (47.9%) of the children come under birth order 1. Most of the child’s birth size was average (64.4%). In terms of the gender, female children found high as of the male. Tribals are indigenous people they live mostly near forest or the rural, remote places. Very high percent (89.1%) of tribal household live in the rural area. In the perspective of religion here majority of Hindu tribals (91.6%) exists as of other religious tribes. Half of the tribes (53.8%) found in the poorest category as well as below the poverty line. Source of drinking water is still unimproved some part of tribals area (16.5%). Surprisingly the toilet facility is not improved (72%) found huge, it’s a major cause of concern. Day to day traditional cooking fuel uses also found very high (91.9%) among the tribes.

Simultaneously, for NFHS-V it’s found that 42.5 % children were stunted, 24.3% wasted and 58.9% underweight. Out of total children’s mother, majority of the mothers (37.7%) age ranges from 20-24 year. Educational level of mother is very low (2.7%) in higher education as its high (45.5%) in secondary education, also no education is not at a negligible point (31.2%). There was 85.3% of child’s mother found anemic. 77.4% children found under Currently breastfeeding. Highest number of children (24.4%) found at their antenatal stage. 45.9% of the children come under birth order 1. Most of the child’s birth size was average (69.2%). In terms of the gender, female children found 0.3% high as of the male. Tribals are indigenous people they live mostly near forest or the rural, remote places. Almost all (97.9%) of tribal household live in the rural area. In the perspective of religion here majority of Hindu tribals (88.7%) exists followed by Christian, Buddhist and other tribes. Most of the tribes (78.1%) found below the poverty line. Source of drinking water is still unimproved some part of tribals area (5.8%). About half of the toilet facility is not improved (53.8%), it’s a major cause of concern. Traditional cooking fuel uses also found very high (90.4%) among the tribes.

Table 3, shows the prevalence of undernutrition (stunted, wasted and underweight) by NFHS-IV (2015-16) & NFHS-V (2019-20), among the sample scheduled tribe children aged 0-59 months, measured by z-scores. There are mid to large variations in childhood undernutrition across mothers, their biological children and the household characteristics. In (

Table 3) it’s found that higher the mothers age group the occurrence of stunting, underweight is high (about 50%), when it comes to mother’s higher educational status there is a no stunting cases found. Interestingly difference between anaemic and non-anaemic mother’s child nutritional status, here its clear that non anaemic mother’s children are high (more than 60%) prone of this undernutrition. In NFHS-IV children in the age group of 13-23months seems high prevalence of undernutrition, but in NFHS-V high prevalence of undernutrition found in the child age group 48-59 months. When the birth order number is above 4

th then the stunting and underweight prevalence is high in both the NFHS rounds. In NFHS-IV only its resulted that very small size of child at birth has been undernourished as of normal size of child at birth. From the sex of child overall the undernutrition is seen among the male children. As rural areas having the backwardness in terms of facilities as compare to urban area, here the data also tells the ground reality that the rural children having more nutritional lacks as compare to the urban. In religion perspective view here in most of the cases Muslim and Christian tribal children are mostly undernourished. When the household comes under below poverty level there obviously lack of nutrition presents, similarly here also the poorest, poorer household’s children are highly nutritionally poor. Beside this factors household sanitation and hygiene also plays important role on children’s nutritional status.

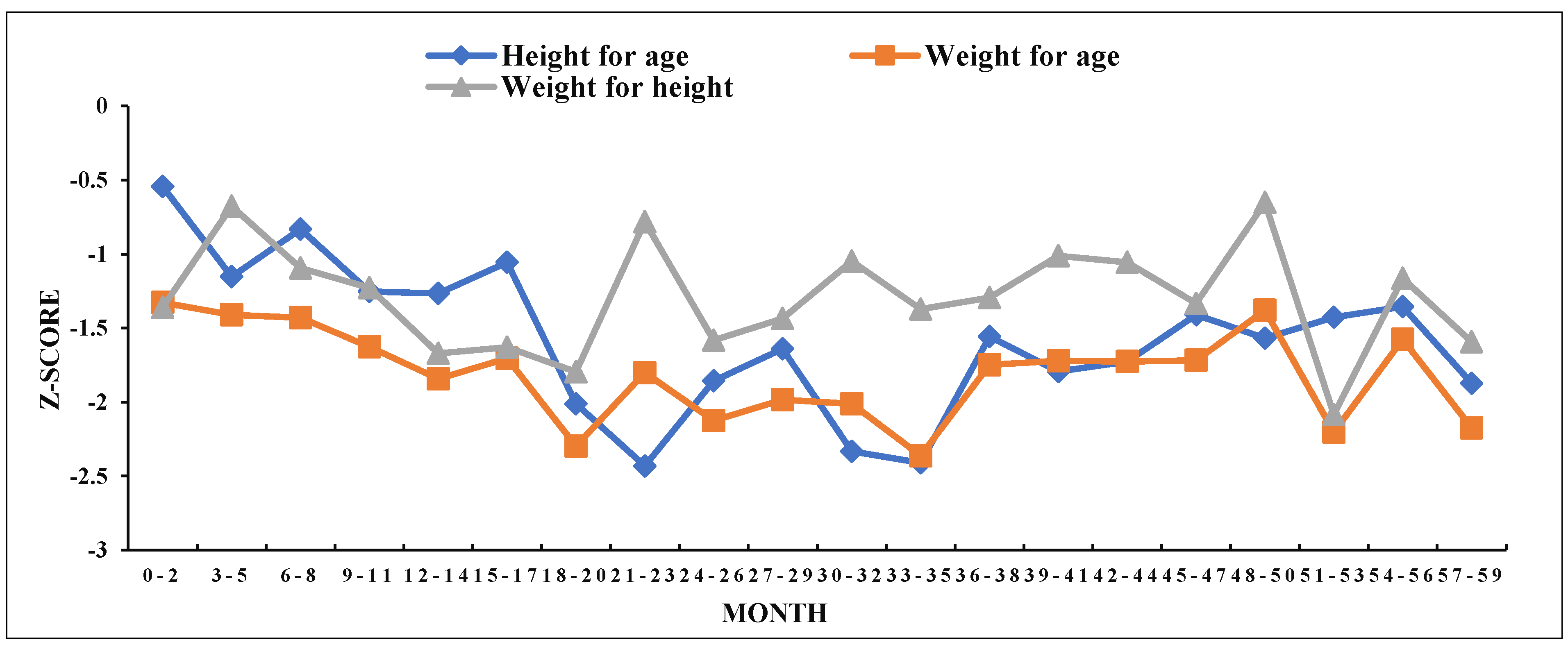

The graph of NFHS-IV (

Figure 2) depicts changes in mean z-scores by age of children aged 0 to 59 months, stratified by three-month age group. The general trends of the z-scores matched those seen in 39 developing nations (Shrimpton, R.

et al., 2001). Weight-for-height scores were lower than the other indices. Both weight-for-age and height-for-age decreased between the ages of 18 and 24 months and before the age of 36 months, which is considered a crucial period in child development (

Growth and development), there is no stabilization. Afterwards the, height-for-age rebounded somewhat and remained between -2.0 and -1.5 until the 60th month of age. Height-for-age and weight-for-height change more than the other indices, ranging from -2.5 to -0.4.

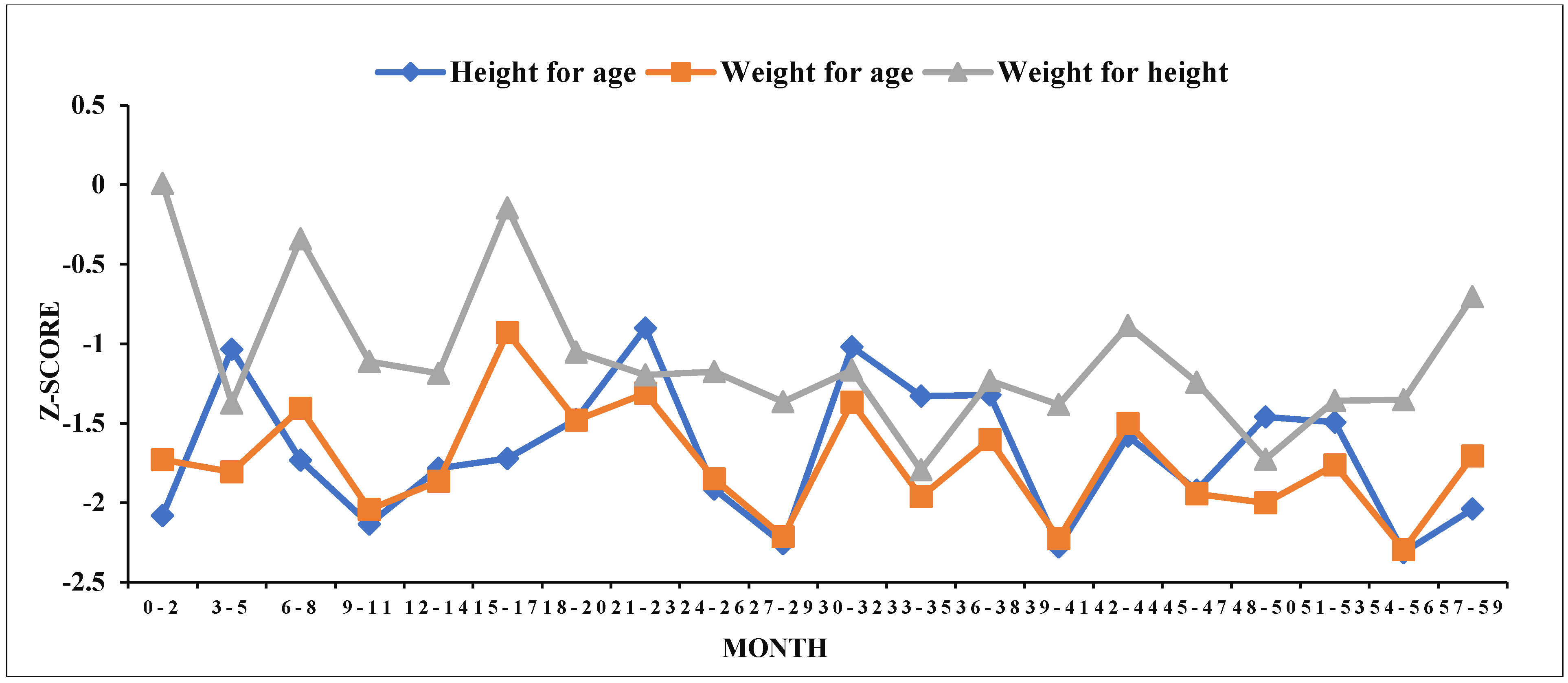

The NFHS-V graph (

Figure 3) depicts changes in mean z-scores by age of children aged 0 to 59 months, segmented by three-month age group. Weight-for-height scores were lower than the other indices. Weight-for-age and height-for-age both dropped significantly between the three age groups (27-29, 39-41 & 54-56 months). Weight-for-height improved little, remaining between -1.75 and -0.75 until the 60th month of life. Height-for-age and weight-for-height changed more than the other indices between -2.4 and -1.

Table 4 shows the mean z-scores of communities for both NFHS-IV and V. It was found that there was a significant difference in children's nutritional condition between the best and poorest communities according to all the z-scores. In NFHS-IV, for contrast, mean height-for-age z-scores ranged from -5.99 in the poorest community to 4.51 in the best. Likewise, height-for-weight z-scores range from -4.87 to 4.12, whereas weight-for-age z-scores range from -5.03 to 1.67, which appears to be less broad than height-for-age and height-for-weight. In addition, the mean height-for-age z-scores in NFHS-V ranged from -5.97 in the poorest community to 5.13 in the best. Similarly, height-for-weight z-scores range from -4.83 to 3.33, whereas weight-for-age z-scores range from -4.99 to 2.14, which appears to be less broad than height-for-age and height-for-weight. The considerable variance in z-scores among communities suggests that there are significant differences at the community level that impact the nutritional condition of tribal children under the age of five.

The association between scheduled tribe under 5year age children’s nutrition status by their anthropometric indices stunted, wasted and underweight (dependent variable), with different variables related to mothers, children’s and their household background characteristics using Pearson chi-square test to see whether there is any association between those selected variables (mother’s age in 5 year age group, educational level, anaemia condition, currently breastfeeding, children’s age group in months, birth order number, size of child at birth, sex of child, type of place of residence, religion, wealth index, drinking water facility, toilet facility, type of cooking fuel). And it’s found significant results (95% confidence interval at 5% level of significance) for all the variables mentioned below (

Table 5).

Table 5, reveals that there are 10 independent variables, which statistically significant at different levels with 3 dependent variables. The independent variables which have been found significant association with stunted are: “Mother’s educational status”, “Child age group in months”, “Childs birth order number”, “Size of child at birth”. Only one independent variable: “Mother’s anaemia status” significant association with wasted. But there are 5 independent variables “Currently breastfeeding”, “child age group in months”, “size of child at birth”, “toilet facility”, “type of cooking fuel” found significant association with underweight.

Beside the significantly associated variables (at 5% level of significance) there, was some independent variables which has a small effect (0.1) with the dependent variable, which shown by the phi correlation coefficient (φ) (strength of coefficient). Here (

Table 5) 3 independent variables “mothers age in 5-year age group”, “mothers anaemia status”, “household wealth index” has small effect with stunting, 4 independent variables “mothers age in 5-year age group”, “Currently breastfeeding”, “Child age group”, “Child birth order number”, “size of child at birth” has small effect with wasting and 6 independents variables “mothers age in 5-year age group”, “mothers educational status”, “mother educational status”, “Child birth order number”, “religion”, “households wealth index” has small effect with underweight.

The association between scheduled tribe under 5year age children’s nutrition status by their anthropometric indices stunted, wasted and underweight (dependent variable), with different variables related to mothers, children’s and their household background characteristics using Pearson chi-square test to see whether there is any association between those selected variables (mother’s age in 5 year age group, educational level, anaemia condition, currently breastfeeding, children’s age group in months, birth order number, size of child at birth, sex of child, type of place of residence, religion, wealth index, drinking water facility, toilet facility, type of cooking fuel). And we found significant results (95% confidence interval at 5% level of significance) for all the variables mentioned below (

Table 6).

Table 6, reveals that there are 14 independent variables and 3 dependent variables are statistically significant at different levels. The independent variables which have been found significant association with stunted are: “Mother’s educational status”, “Childs birth order number”, “type of place of residence”. Only one independent variable: “Mother’s age in 5-year groups” significant association with wasted. But there are 6 independent variables “Mother’s educational status”, “sex of child”, “type of place of residence”, “households wealth index”, “toilet facility”, “type of cooking fuel” found significant association with underweight.

Beside the significantly associated variables (at 5% level of significance) there, was some independent variables which has a small effect (0.1) with the dependent variable, which shown by the phi correlation coefficient (φ) (strength of coefficient). Here (

Table 6) 3 independent variables “mothers age in 5-year age group”, “religion”, “wealth index” has small effect with stunting, 4 independent variables “mother’s educational status”, “Child birth order number”, “size of child at birth”, “wealth index” has small effect with wasting and 3 independents variables “Child birth order number”, “size of child at birth”, “religion” has small effect with underweight.

There are many reasons that lied upon different factors, among such factors there are some important socio-demographic factors that determines the children nutritional status, which is found from the various evidenced based studies as discussed in this study. Children of uneducated mothers are at a higher risk of malnutrition (Meshram, I.I. et al., 2012). Also, the Anaemia is such condition where its shown to be much worse within tribal children when compared to other groups, and a significant number of children are undernourished, with mothers as well undernourished (Das, S., and H. Sahoo, 2011). Whereas, also the findings differ in that older children have a higher risk of malnutrition when compared to new-borns (Meshram, I.I. et al., 2012). But, in another study its found that children aged 1-3 years were at a higher risk of malnutrition than older children (3-6 years), (Bisai, S., et. al., 2008). Therefore, gender wise, Male under-five children have a higher probability than females to be underweight, stunted, and wasting (Meshram, I.I. et al., 2012). In research that has been done in Maharashtra, it was also shown that males have a higher risk of malnutrition than girls (Meshram, I.I. et al., 2012). It is often assumed that when parents have a new child that requires a lot of attention and care, they pay less attention to their older children (Das, S. and Sahoo, H., 2011).Overall its insights that, Underweight, stunting, and wasting are the three basic markers used to identify undernutrition. They are typically associated with recurrent exposure to poor economic situations, inadequate sanitation, and the complex effects of insufficient energy and nutritional intakes and illness (Joshi, H.S. et al., 2016). Similarly key factors of child nutritional status are the availability of good water supplies and sanitary conditions (UNICEF, 1990). Socioeconomic factors, such as poverty, illiteracy, a lack of understanding about the quality of food products, and inadequate sanitation, are the factors related with children's undernutrition.

7. Conclusion & Recommendations

This study utilized scheduled tribe mother, children and household characteristics status as a proxy of the stunting, wasting and underweight and examined its effect and association on undernutrition of scheduled tribe children under age 0-59 months. To find out the determinant factors which are associated to the nutritional status of scheduled here some selected 14 independent variables with 3 anthropometric nutritional indices taken. And to analyse this we use recent NFHS-V (2019-20) and previous NFHS-IV (2015-16), where the data contains 354 sample (scheduled tribe mother with their biological children) in NFHS-IV and 294 sample (scheduled tribe mother with their biological children) in NFHS-V in West Bengal. After the analysis it’s found that in NFHS-IV, 38.9% children were stunted and the selected variables “mother’s educational status”, “child age group in months”, “child birth order number”, “size of child at birth” has significant effect on child stunted status. Where, there was 29.4% of children were wasted, and the variable “mother anaemia status” only has a significant effect, but in case of underweight 42.9% of children, and its significant with the variable “currently breastfeeding”, “child age group in months”, “size of child at birth”, “toilet facility”, “type of cooking fuel”. Similarly, in NFHS-V, stunted children were 42.5% and its significantly associated with the variables “mother’s educational status”, “birth order number”, “type of place of residence”. Wasted children was 24.3% and its significantly associated with the variable “mother age in 5year groups”. And underweight children exist 58.9%, which significantly associated with “mother’s educational status”, “sex of child”, “type of place of residence”, “wealth index”, “toilet facility”, “type of cooking fuel”. In this study we conclude that, mother’s nutritional status plays an important dominants factor on malnutrition (low weight-for-age) of children under age 5 in West Bengal.

These nutrient insufficiency throughout childhood can result in irreversible cognitive development, poor health conditions, and a higher mortality threat, and has also been linked to inadequate human capital creation, potentially reducing the country's economic output in the long term (Menon, P. et al., 2018). As a result, well-planned poverty alleviation initiatives, as well as universal health and nutrition education, are required, with a specific emphasis on both the economically and socially vulnerable segments of the population, particularly the primitive scheduled tribes as well as the indigenous tribes. Additional anganwadi and ICDS centres must be constructed, particularly in the remote and tribal regions, to protect children and mothers from undernutrition (Ahmad Khanday, Z. and Akram, M., 2012). Additionally, the facilitating determinants, which are the administrative, economical, societal, cultural, and environmental circumstances that should be supportive in order to provide optimal nourishment for children and women, should be in existence (UNICEF Conceptual Framework). Strategic plan and integrating the work of Anganwadi workers underneath the Integrated Child Development Service (ICDS), Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA) under National Rural Health Mission, and effective community involvement will lead to improved delivery of services to target groups at the grass roots level of the community (Menon, P. et al., 2018).

Funding

There was no funding received to assistance with the creation of this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The corresponding author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Credit Author Statement

Manabindra Barman1: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Writing-original draft. Dr. Indrajit Roy Chowdhury2: Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Writing-reviewing.

Abbreviations

Scheduled Tribe (ST), Demographic Health Survey (DHS), National Family Health Survey (NFHS), Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW).

References

- Ahmad Khanday, Z. and Akram, M. (2012) “Health status of marginalized groups in India,” International Journal of Applied Sociology, 2(6), pp. 60–70. [CrossRef]

- Babu, B.V. and Kusuma, Y.S., 2007. Tribal health problems: some social science perspectives. Health dynamics and marginalised communities. Jaipur: Rawat Publications, pp.67-95.

- Bisai, S. , Bose, K. and Ghosh, A., 2008. Prevalence of undernutrition of Lodha children aged 1-14 years of Paschim Medinipur district, West Bengal, India.

- Black, R.E. et al. (2008) “Maternal and child undernutrition: Global and regional exposures and health consequences,” The Lancet, 371(9608), pp. 243–260. [CrossRef]

- Das, S. and Sahoo, H. (2011) “An investigation into factors affecting child undernutrition in Madhya Pradesh,” The Anthropologist, 13(3), pp. 227–233. [CrossRef]

- Dey, U. and Bisai, S. (2019) “The prevalence of under-nutrition among the Tribal Children in India: A systematic review,” Anthropological Review, 82(2), pp. 203–217. [CrossRef]

- Growth and development, ages 12 to 24 months PeaceHealth. Available online: https://www.peacehealth.org/medical-topics/id/te7089 (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- India Global Hunger Index (GHI) - peer-reviewed annual publication designed to comprehensively measure and track hunger at the global, regional, and country levels. Available online: https://www.globalhungerindex.org/india.html (accessed on 7 December 2022).

- Joshi, H.S. et al. (2016) “Sociodemographic correlates of nutritional status of under-five children,” Muller Journal of Medical Sciences and Research, 7(1), p. 44. [CrossRef]

- Menon, P. et al. (2018) “Understanding the geographical burden of stunting in India: A regression-decomposition analysis of district-level data from 2015–16,” Maternal & Child Nutrition, 14(4). [CrossRef]

- Meshram, I. I., Mallikharjun Rao, K., Balakrishna, N., Harikumar, R., Arlappa, N., Sreeramakrishna, K., & Laxmaiah, A. (2018). Infant and young child feeding practices, sociodemographic factors and their association with nutritional status of children aged <3 years in India: Findings of the National Nutrition Monitoring Bureau Survey, 2011–2012. Public Health Nutrition, 22(1), 104–114. [CrossRef]

- Meshram, I.I., Arlappa, N., Balakrishna, N., Laxmaiah, A., Mallikarjun Rao, K., Gal Reddy, C., Ravindranath, M., Sharad Kumar, S. and Brahmam, G.N.V., 2012. Prevalence and determinants of undernutrition and its trends among pre-school tribal children of Maharashtra State, India. Journal of Tropical pediatrics, 58(2), pp.125-132.

- Meshram, I.I., Arlappa, N., Balakrishna, N., Rao, K.M., Laxmaiah, A. and Brahmam, G.N.V., 2012. Trends in the prevalence of undernutrition, nutrient and food intake and predictors of undernutrition among under five-year tribal children in India. Asia Pacific journal of clinical nutrition, 21(4), pp.568-576.

- Padmanabhan, P.S. and Mukherjee, K. (2016) “Nutrition in Tribal Children of Yercaud Region, Tamil Nadu,” Indian Journal of Nutrition, 3(2).

-

Scheduled tribes of west Bengal, Tribal Development Department, Government of West Bengal. Available online: https://adibasikalyan.gov.in/html/st.php (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Shrimpton, R. et al. (2001) “Worldwide timing of growth faltering: Implications for nutritional interventions,” Pediatrics, 107(5). [CrossRef]

-

Status of IMR and MMR in India (2022) Press Information Bureau. Available online: https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1796436 (accessed on 7 December 2022).

- Tribal Nutrition UNICEF India. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/india/what-we-do/tribal-nutrition#:~:text=About%2040%20per%20cent%20of,of%20them%20are%20severely%20stunted. (accessed on 1 December 2022).

-

UNICEF Conceptual Framework (no date) UNICEF. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/documents/conceptual-framework-nutrition (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Van de Poel, E. (2008) “Socioeconomic inequality in malnutrition in developing countries,” Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 86(4), pp. 282–291. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (1995) Physical Status: The Use and Interpretation of Anthropometry. rep. Geneva: WHO.

- Xaxa, V., 2011. The status of tribal children in India: A historical perspective. IHD-UNICEF working paper, (7).

- Xaxa, V., 2014. Report on the high-level committee on socio-economic, health and educational status of tribal communities of India.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).