1. Introduction

Blastomycosis is an endemic fungal disease often manifested as pulmonary disease, however it can disseminate to the skin, bones, and genitourinary tract. [

1] This may include pulmonary disease with an indolent pneumonia, skin disease manifested as verrucous skin lesions and cold abscesses, bone disease with painless osteomyelitis and chronic draining sinus tracts, and genitourinary disease leading to prostatitis, epididymitis, endometritis, salpingitis, and tubo-ovarian abscess [

1]. Additionally, blastomycosis is present endemically in North America, notably often bordering areas surrounding the Mississippi, Ohio and St. Lawrence Rivers and the Great Lakes. Particularly in Canada, blastomycosis is present amongst four Canadian provinces from Saskatchewan to Quebec [

1]. In such endemic regions, Blastomyces spp. often inhabit an ecologic niche of forested, sandy soils, decaying vegetation or organic material, and rotting wood located near water sources [

1].

While most infections are sporadic, occupational and recreational activities that disrupt soil such as construction, clearing brush or cutting trees, hunting, canoeing, boating and fishing have all been associated with outbreaks of the disease [

1]. Outbreaks of Blastomyces infections have been reported throughout the United States, ranging from endemic regions to areas of Colorado, postulated to be related to vector transmission with prairie dog relocation [

1]. However, undescribed in the literature is the association of blastomycosis with the handling of wood with axe throwing, a leisurely activity often performed in a group setting or sporting event. We present a case report of a young, healthy male in Southern California diagnosed with disseminated blastomycosis with a constellation of notable physical exam findings in the setting of a unique occupational exposure of axe throwing.

2. Case Report

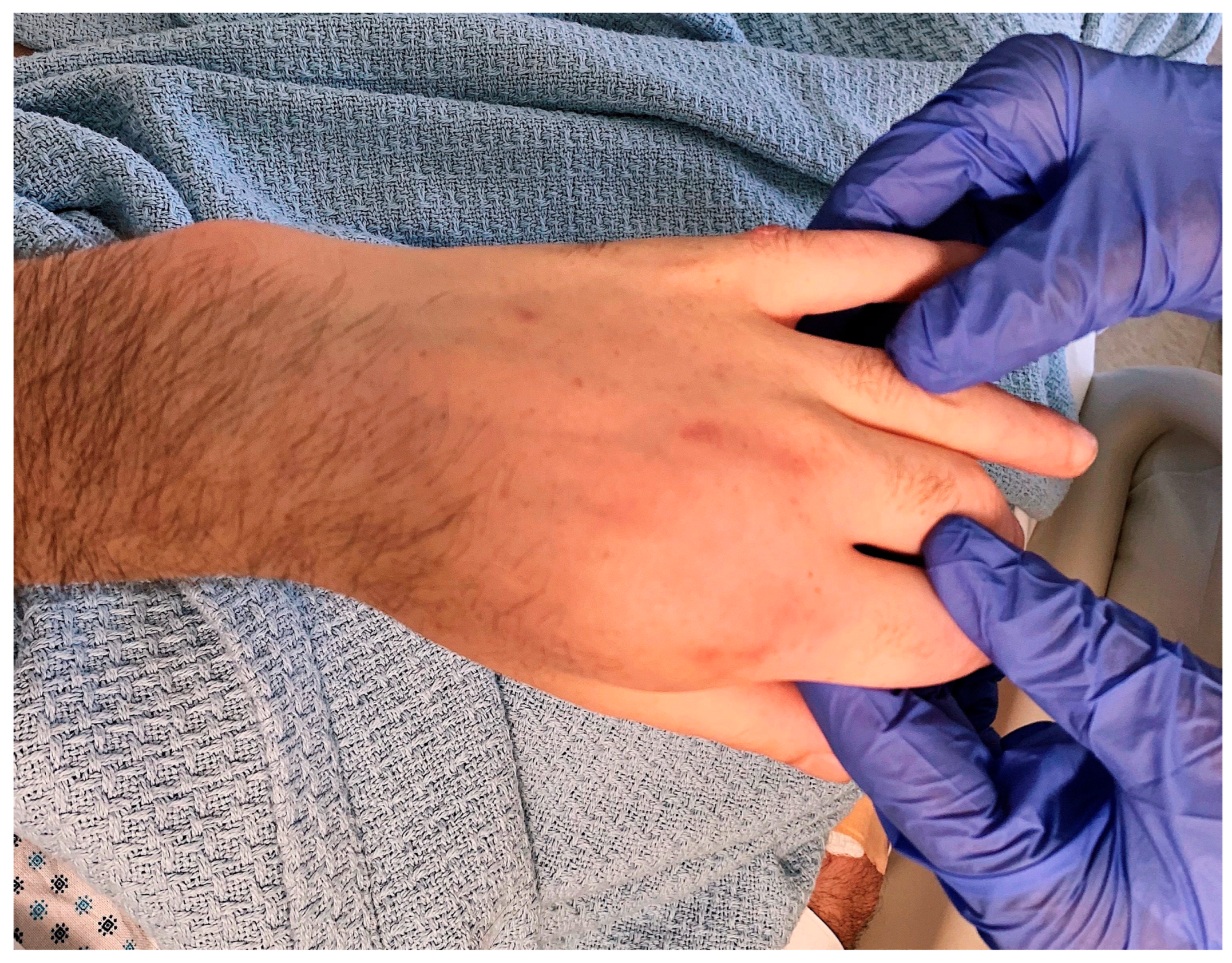

A 29-year-old man presented to the hospital with a three-month history of non-productive cough and progressively worsening joint pain in his wrists, knees, and ankles. He moved from Toronto, Canada to Los Angeles, California eight months prior to his presentation. He previously was unemployed in Toronto and began working at an axe throwing factory upon moving to Los Angeles; his duties included chopping wood for customers to use. He reported having a single monogamous female partner and no recent interactions with livestock, or other animals outside of his pet dog. His initial presenting symptom several months prior was the presence a cyst in his left lower abdomen which eventually evolved into an abscess with purulent drainage. Several weeks later, he developed a verrucous lesion on his left face near his nasolabial fold, followed by other similar lesions throughout his face over the next several months (

Figure 1). Gradually, he began having a worsening non-productive cough leading to fatigue and dyspnea on exertion, and subsequently, he presented with swelling in both hands, knees, and ankles. Finally, he was found to have a soft, fluctuant mass in his right occipital region and fixed, hard mass across the roof of his mouth (

Figure 1). He denied the presence of fevers throughout his course. On examination, he had weight loss with marked cachexia and temporal wasting in addition to the aforementioned physical exam findings. The absence of fevers and his joint swelling without erythema or warmth pointed towards a more indolent infectious etiology.

Lab work was significant for an initial serum white blood cell count (WBC) of 15.5 K/cumm [4.5-10.0 K/cumm], hemoglobin 10.9 g/dL [13.5-16.5 g/dL], and platelet count of 627 K/cumm [160-360 K/cumm]. Serum creatinine was 0.58 mg/dL [0.50-1.20 mg/dL] and liver function test (LFT) results were within normal limits. The high sensitivity C-reactive protein was 264.5 mg/L [0.0-7.0 mg/L] and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 77 mm/hr [no reference range]. Notably, 4th generation HIV Ag/Ab testing was negative.

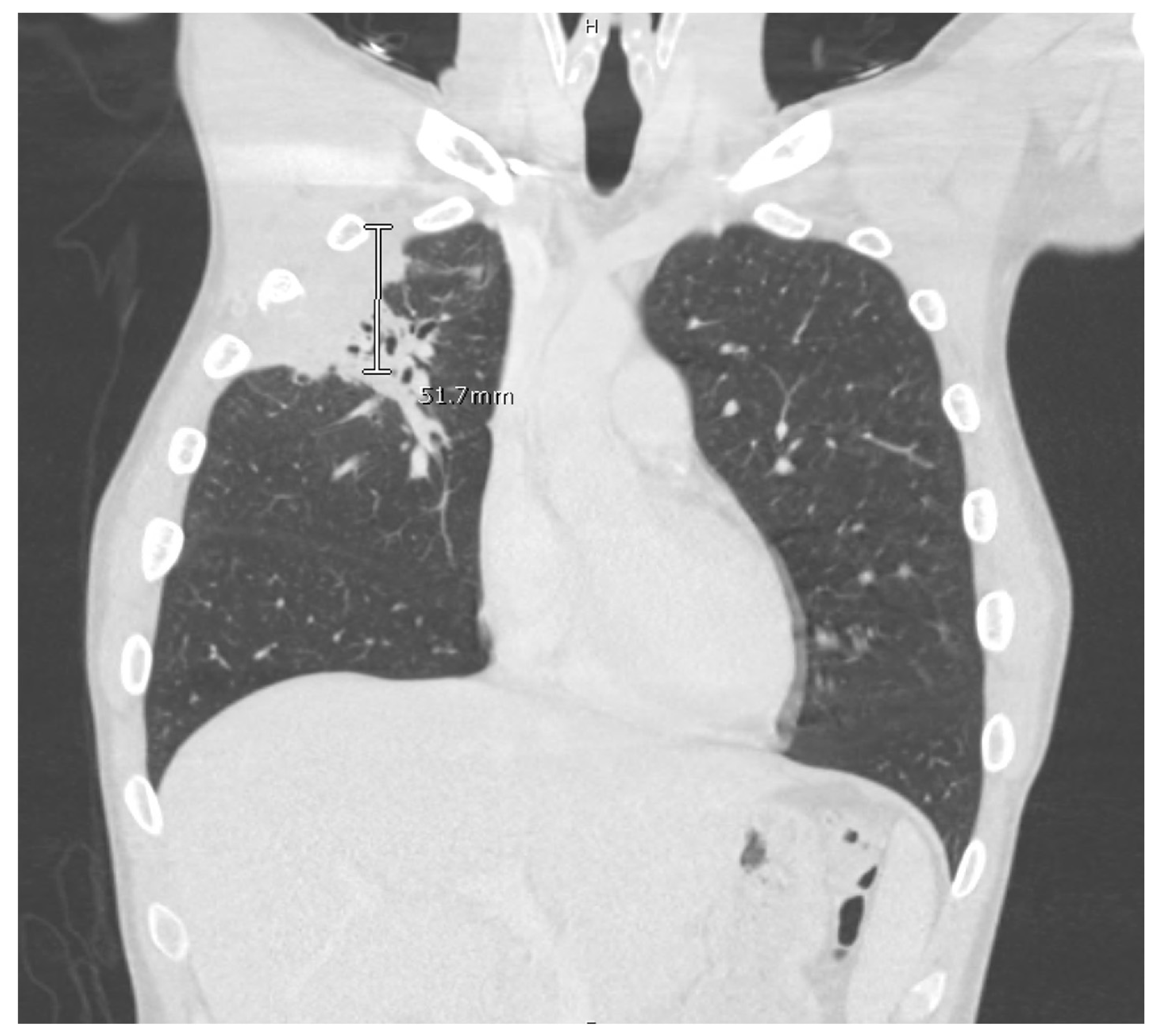

Computed tomography (CT) scan of his chest and abdomen revealed a right upper lobe cavitary lesion abutting the ribs and a sinus tract from his left ischium to the skin over his left lower abdomen (

Figure 2). Additionally, a magnetic resonance image (MRI) of his head was obtained which demonstrated a mass extending from his right occipital skull with evidence of skull erosion as well (

Figure 3).

Given the MRI findings, a lumbar puncture was performed for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis which showed CSF WBC 0/cumm [0-9/cumm], RBC 0/cumm [0/cumm], Glucose 66 mg/dl [40-70 mg/dL], and Protein 28 mg/dL [15-45 mg/dL]. CSF bacterial, fungal, and acid-fast bacilli (AFB) cultures were negative. A synovial fluid analysis of his right knee was also taken which was described as cloudy fluid demonstrating an RBC count of 151/cumm [no reference range], WBC count of 4,242/cumm [0-199/cumm] with 87% neutrophils, 9% lymphocytes, and 4% monocytes, and no crystals present. Bacterial, fungal, and AFB cultures of the synovial fluid of the knee were negative as well.

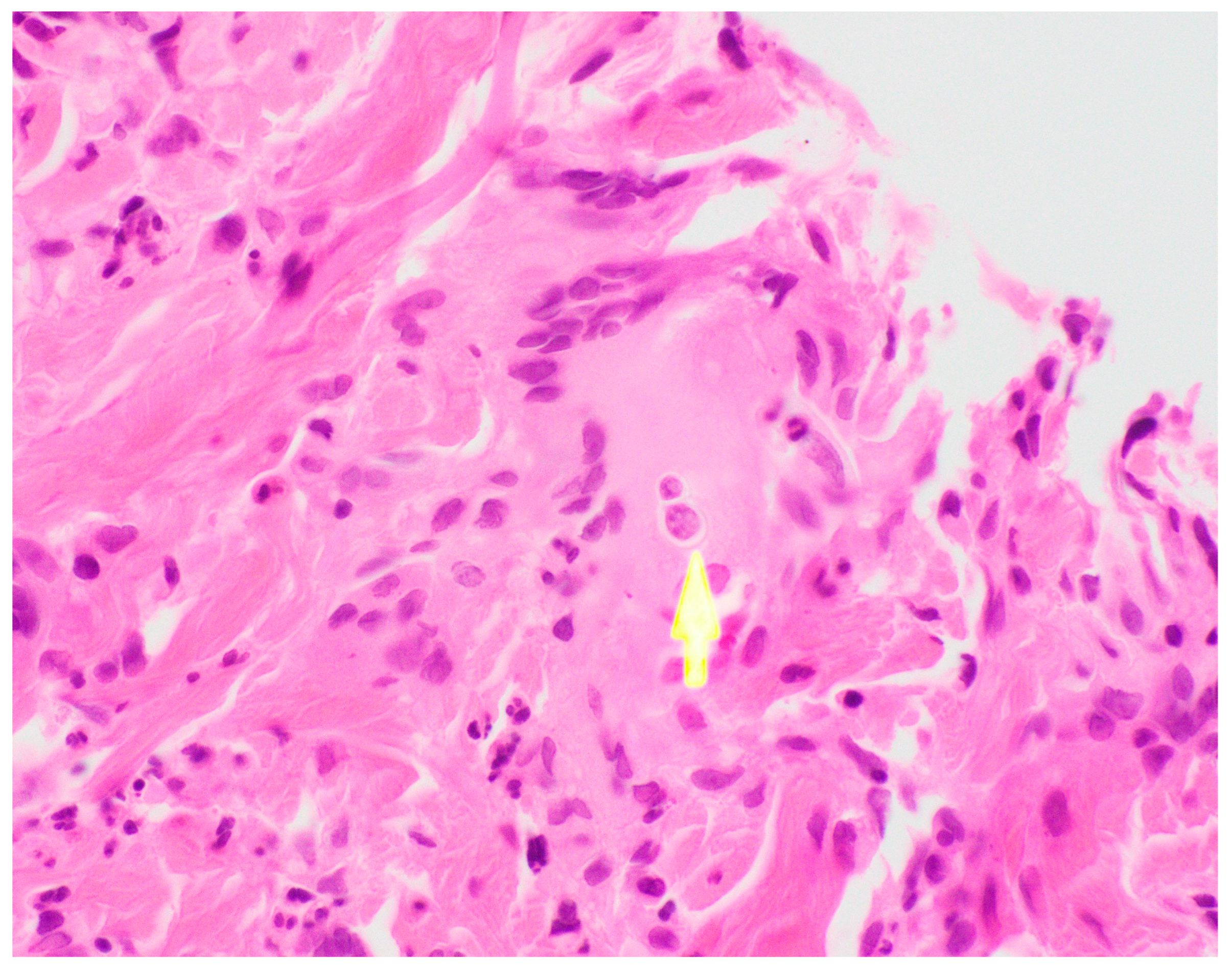

Ultimately, a punch biopsy of his left second metacarpophalangeal joint was taken in addition to cultures from the left hip sinus tract drainage which revealed the presence and growth of

Blastomyces dermatitidis, respectively (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). Serology testing was also ordered, which was positive for Blastomyces antibody immunodiffusion (ID), though negative for Blastomyces antibody complement fixation (CF). Notably, a urine histoplasma antigen test was positive with a result of > 25.0 ng/mL with a negative histoplasma antibody ID test, likely indicating a component of cross-reactivity in the presence of

Blastomyces dermatitidis.

In light of the diagnosis, treatment with liposomal amphotericin was initiated for two weeks. Throughout his liposomal amphotericin therapy, he began experiencing improvement in his lesions and respiratory symptoms. Upon completion of his two weeks of intravenous therapy, he was started on oral itraconazole treatment. He followed up several months following the initial diagnosis in the infectious disease clinic while on oral itraconazole, with full clinical recovery and normalization of his cutaneous, mucosal, and joint findings. Ultimately, he was treated with a full twelve months of itraconazole therapy, with appropriate serum therapeutic dosing levels, until discontinuation of therapy.

3. Discussion

Our case highlights several important clinical aspects surrounding blastomycosis. For instance, the patient presented with an indolent, disseminated disease which illustrates the full spectrum of characteristic findings seen with the disease [

1]. However, his presentation also included mucosal findings with a fixed mass on his hard palate which improved with targeted antifungal therapy. Mucosal lesions are infrequently described in the literature, as they are uncommon with Blastomyces infections [

2]. The indolent nature of the Blastomyces infection and non-specific clinical manifestations often lead to a delayed diagnosis, particularly when not considered on the differential diagnosis in a non-endemic region and when an atypical presentation may be present.

The diagnosis of blastomycosis may be difficult even with a high index of clinical suspicion. A key factor to achieving a clinical diagnosis is a compatible social history, both to clarify an endemic risk and activities associated with acquisition of the disease. Blastomyces in household pets, such a as dogs, can suggest a common source of exposure that may predict human infection, which our patient endorsed having a pet dog that would frequent the outdoors in Canada [

1]. Outside of objective, radiographic data, the diagnosis of blastomycosis can also be confirmed via culture and microscopy [

1]. Additionally, serology may be helpful to support a diagnosis, though often encountered in the context of poor sensitivity and specificity. In our case, the Blastomyces antibody ID was positive, and the antibody CF was negative. However, given the microscopic, pathologic results consistent with Blastomyces and the growth of

Blastomyces dermatitidis on culture a definitive diagnosis had been established.

Cross reactivity may be seen with histoplasma antigen assays in the presence of alternate endemic mycoses [

3]. Particularly in this case, the patient may have had an endemic risk factor for histoplasmosis, though not highly endemic geographically [

4]. In our case, the histoplasma antigen was markedly positive, which may raise confusion for an alternate diagnosis. However, the presence and growth of

Blastomyces dermatitidis helped to determine the ultimate etiology of the patient’s presentation. Notably, treatment for disseminated blastomycosis may be different in terms of a recommended regimen for intravenous amphotericin, which fortunately the diagnosis was achieved to offer the patient optimal therapy.

Outside of behavior risk factors, there are no frequently described cases where HIV/AIDS as an immunocompromising condition plays a role in the acquisition of blastomycosis and its dissemination [

5]. In sampling hospital admissions for patients diagnosed with blastomycosis, a concomitant diagnosis of HIV/AIDS is seen in approximately 5% of cases, pointing to the fact that it may not represent as an opportunistic infection [

5]. Our patient was sexually active in a monogamous relationship, but his HIV testing was negative, lowering the suspicion of an opportunistic infection from AIDS that may infrequently be seen with blastomycosis, and more frequently seen with other endemic mycoses such as histoplasmosis [

6].

There is an average incubation period of approximately three to three and a half months for Blastomyces infections [

7]. In our case, the patient moved from Toronto to Los Angeles eight months prior to his presentation and began handling wood at work imported from northern regions of North America, presumably contracting his infection in a non-endemic region. This raises the suspicion for an occupational exposure, irrespective of his history of residing in an endemic region in Canada prior to moving to Los Angeles. The patient reported that the wood related to axe throwing was imported throughout various regions in North America, and would often sit out in rainy weather before being curated and prepared for axe throwing. As Blastomyces often grows with decaying, moist wood, this is likely the optimal environment for imported wood to be infected with Blastomyces [

1]. Taken into account, the patient’s incubation period coincides with a prolonged duration beyond the described incubation period characteristic of blastomycosis, representing a unique circumstance for the inoculation of the disease.

Another highlight of this case is the fact that the diagnosis was made in Los Angeles, California. Blastomycosis is a disease seen prominently in North America, namely in the northern region of the continent [

8]. While Blastomyces is endemic to such a region, approximately eight percent of hospitalization for Blastomyces infections occur outside of endemic regions. However, within this context, California is a rare region for such a hospitalization to occur [

5]. In our case, not only was the case diagnosed in Los Angeles, but the patient is assumed to have contracted the infection in Los Angeles as well due to an occupational exposure. Such a diagnosis may be difficult for local providers to establish given the lack of experience with this particular pathogen causing endemic mycosis. To date, outbreaks have been reported throughout various states in the United States, but no outbreak has been reported in California [

5,

7]. While our case may not represent an outbreak, the potential based on exposure risk may be a harbinger for a potential future outbreak in a non-endemic region.

Lastly, the occupational exposure in this case represents a new risk factor. There is an undescribed correlation between the occupation and such an infection both in medical literature and the lay population; this may implicate axe throwing as an emerging occupational exposure that may be linked to blastomycosis. Axe throwing is an age-old activity that has gained popularity in Canada for nearly a decade and has now expanded to both a sporting and leisurely activity on an international level [

9]. In communities throughout the United States, axe throwing is an opportunity for people to gather and partake in the sport both in the capacity of an organized league and social gathering.

9 As axe throwing becomes more popular, it will likely expand beyond the North American region to other parts of the world. Certainly, an important role around the risks of infection with axe throwing is the process of wood handling. As wood is often exported throughout different regions of the country, this profession involves both workers and consumers to become more exposed to several types of wood and the endemic fungi that are regionally linked to the wood. With this activity gaining increased popularity internationally, the risks should be acknowledged to safely handle wood and materials. This should prompt providers to become aware of the risk factor of this sport and to appropriately raise suspicion in the correct clinical context to screen for this activity in patients.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, at our institution and based on the region in Southern California, blastomycosis is not a routine diagnosis. This case represents a clinical syndrome of disseminated blastomycosis with hallmark findings with skin and bone involvement with the presence of sinus tracts, in addition to unique findings such as the oral cavity and hard palate involvement. While there was concomitant radiographic imaging with erosions present, the diagnosis was made both based on clinical presentation and the forthcoming of the patient’s profession working at an axe throwing factory with wood being imported from the northern regions of the North America. Postulated that the endemic history of residing in Canada may be pertinent, the incubation period of the disease may point away from the inoculation occurring at that time given his departure from Canada 8 months prior to his presentation. Fortunately, the patient responded well to the intravenous amphotericin therapy for a two-week course and completed twelve months of itraconazole therapy with resolution of his symptoms clinically. Importantly is the presence of this new occupational risk factor of axe throwing, that is gaining increasingly popularity. Risk factors related to the sport rely on the handling and exposure to wood, which may serve as a vector for the transmission of endemic mycoses outside of classically thought to believe endemic regions. As the sport gains greater popularity worldwide, attention should be brought via possible surveillance to help determine if increased cases and outbreaks are being observed. On the level of the provider, it should be explored moving forward to determine the risks of workers and consumers who may be exposed to Blastomyces both nationally and internationally.

Author Contributions

All authors have substantially contributed to the conceptualization, drafting, and editing of the case report. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

We would like to thank the patient for allowing us to be involved in his care and describe his clinical course. The patient’s written consent has been obtained prior to publication and conforms with the current standards in the country of origin for patient consent and confidentiality.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- McBride JA, Gauthier GM, Klein BS. Clinical Manifestations and Treatment of Blastomycosis. Clin Chest Med. 2017;38(3):435-449. doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2017.04.006. [CrossRef]

- Reder PA, Neel HB. Blastomycosis in otolaryngology: review of a large series. Laryngoscope. 1993; 103:53-58. doi.org/10.1288/00005537-199301000-00010. [CrossRef]

- Wheat J, Wheat H, Connolly P, Kleiman M, Supparatpinyo K, Nelson K, Bradsher R, Restrepo A. Cross-reactivity in Histoplasma capsulatum variety capsulatum antigen assays of urine samples from patients with endemic mycoses. Clin Infect Dis. 1997 Jun;24(6):1169-71. doi: 10.1086/513647. PMID: 9195077. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention. Sources of Histoplasmosis. National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Centers of Diseases Control and Prevention. 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/histoplasmosis/causes.html.

- Seitz AE, Younes N, Steiner CA, Prevots DR. Incidence and trends of blastomycosis-associated hospitalizations in the United States. PLoS One. 2014 Aug 15;9(8):e105466. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105466. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan JE, Benson C, Holmes KK, Brooks JT, Pau A, Masur H; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); National Institutes of Health; HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Guidelines for prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from CDC, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2009 Apr 10;58(RR-4):1-207; quiz CE1-4. PMID: 19357635.

- Klein BS, Vergeront JM, Weeks RJ, Kumar UN, Mathai G, Varkey B, Kaufman L, Bradsher RW, Stoebig JF, Davis JP. Isolation of Blastomyces dermatitidis in soil associated with a large outbreak of blastomycosis in Wisconsin. N Engl J Med. 1986 Feb 27;314(9):529-34. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198602273140901. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention. Sources of Blastomycosis. National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Centers of Diseases Control and Prevention. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/blastomycosis/causes.html.

- Knibbs K. Unbury the Hatchet: How Competitive Ax-Throwing Went From a Canadian Fad to a Global Pastime. The Ringer. 2018 Oct 18 https://www.theringer.com/sports/2018/10/18/17992498/axe-throwing-organized-sport.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).