1. Introduction

Lectins are carbohydrate-binding proteins that play significant roles in the interactions between biological molecules and cells by recognizing specific carbohydrate chains. They are present in a wide range of organisms, from viruses to higher mammals and function in the recognition of complex glycan structures with great variety due to the combinations of constituent monosaccharides and their linkages [

1,

2]. Originally discovered in plant seeds, lectins agglutinate erythrocytes by binding to the cell surface glycans and crosslinking them. They play crucial roles in recognizing cell surface glycans as glycoproteins and glycolipids, which are essential for maintaining cell membrane structure and function as receptors to transmit intercellular information. Lectins have also been found in various animal tissues and fluids and serve as essential tools in the recognition of molecules and cells, especially in cell adhesion, immunity, and molecular transport [

3].

Animal lectins are categorized into several families based on the structures of their carbohydrate-recognition domains (CRDs) [

3,

4]. Among them, galectins [

5] and C-type lectins [

6], are the two major families, which are widely distributed in various organisms and tissues and include several subfamilies. Galectins are characterized by their binding specificity for β-galactosides, such as N-acetyllactosamine (Galβ1-4GlcNAc) [

5,

7]. The CRD of galectins shares a common structural feature of a β-sandwich composed of approximately 135 amino acid residues. Galectins have a wide range of functions, including development/differentiation, apoptosis, cell adhesion, and RNA splicing. In contrast to galectins, whose specificities are mostly restricted to β-galactosides, the C-type lectins, named based on their Ca

2+-dependency [

8], contain CRDs that vary in carbohydrate-binding specificities. In mammals, most of the C-type CRDs are found as carbohydrate-binding modules fused to different domains [

6]. One Ca

2+ ion is usually located in their carbohydrate binding site and serves to bind specific carbohydrates by forming coordinate bonds [

9]. A number of C-type CRD-containing receptors play important roles in the innate immune system [

10,

11,

12].

Other families of animal lectins also play crucial roles in various cellular functions, such as protein folding (calnexin, calreticulin) [

13,

14], transport of secretory proteins (L-type lectin) (3, 14), transport of lysosomal proteins (P-type lectin) [

15], cell adhesion and immune responses (siglec, I-type lectin) [

16,

17,

18]. These lectins are localized to more specific sites to perform specialized functions involving the recognition of carbohydrate chains. The involvement of various lectins in recognition processes between intercellular molecules indicates the importance of carbohydrate chains as versatile tags that distinguish molecules.

While most information concerning the structure and function of animal lectins has been obtained from higher vertebrates, particularly mammals, an increasing number of studies on lectins of other species, including invertebrates, have been reported recently and shown to play important roles in their defense mechanisms. Since invertebrates lack acquired immunity, lectins may be particularly important in innate immunity to recognize foreign molecules. This review will mainly focus on lectins from marine animals, particularly invertebrates. These animals encompass an extremely diverse group of species, and therefore, novel lectins with unique structures and functions are expected to exist. Elucidating their structures and functions may provide valuable insights into the roles of lectins with an evolutionary perspective.

2. Involvement of C-type lectins in immunity

C-type lectins contain C-type CRDs comprising 120-130 amino acid residues, which require Ca

2+ ions for their carbohydrate-binding activity. However, various proteins with C-type CRD-like structures that function without Ca

2+ have also been found, and they are referred to as C-type lectin-like domains (CTLDs). Proteins containing CTLD play a wide range of functions and can recognize ligands other than carbohydrates, such as proteins, lipids, and inorganic compounds [

6,

9]. Many C-type lectins are known to be involved in innate immunity as pattern-recognition molecules (PRMs) [

19]. In mammals, most C-type lectins are composed of C-type CRDs and different domains to exert specific functions. Particularly, many C-type lectins are involved in immunity in both soluble and membrane-bound forms. The latter includes a variety of receptors expressed on the surface of immune cells through the transmembrane domain [

11].

The mammalian mannose-binding lectin (MBL) was the first C-type lectin to have its CRD structure determined by X-ray crystallography [

20]. MBL is a soluble C-type lectin found in mammalian serum, composed of an N-terminal collagen-like domain and a C-type CRD. It forms a trimer linked at its collagen-like and cysteine-rich domains, which further assemble into larger bouquet-like oligomers. In this structure, the carbohydrate-binding sites of the CRDs are oriented in the same direction to bind to the surface mannose-rich glycans on microorganisms. MBL acts as a PRM that recognizes characteristic structures of microorganisms, thereby activating the lectin pathway of the complement system through the activation of MBL-associated serine proteases (MASPs) [

21,

22,

23]. Similar C-type lectins containing collagen-like domains are categorized as collectins, including pulmonary surfactant proteins, SP-A and SP-D [

24]. Membrane-bound C-type lectins on the surface of lymphocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells serve as receptors for the surface molecules of pathogens [

25].

In contrast to the C-type CRDs found in mammals, many invertebrate C-type lectins consist solely of a single C-type CRD in a polypeptide chain, while some are composed of multiple CRDs or other functional domains [

26,

27,

28]. Invertebrate C-type lectins have been shown to agglutinate microorganisms by binding to surface molecules such as lipopolysaccharides, peptidoglycans, and β-glucans, which leads to phagocytosis [

27,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. Additionally, their expression is enhanced when challenged with microorganisms [

31,

34,

35,

36]. These observations strongly suggest that invertebrate C-type lectins function as PRMs and play a role in innate immunity. The importance of C-type lectins for the immune system in invertebrates is supported by the wide distribution of C-type CRDs or C-type CRD-like domains (CTLDs) among different animal species [

37,

38,

39].

3. Carbohydrate recognition mechanisms of marine invertebrate C-type lectins

The carbohydrate-binding mechanism of C-type lectin CRDs was elucidated through X-ray crystallographic analysis of rat mannose-binding lectin (MBL) MBP-A [

20]. The CRD of MBP-A contains three Ca

2+ ions at the top of the domain, one of which is involved in mannose binding through coordinate bonds with the 2- and 3-hydroxy groups of mannose (

Figure 1A) [

6].The binding of mannose is further stabilized by a hydrogen bond network between the 2- and 3-hydroxy groups and nearby residues, Glu185 and Asn187. In addition to Pro186, these residues are known as the EPN (Glu-Pro-Asn) motif that determines mannose-specificity of C-type CRDs, while the QPD (Gln-Pro-Asp) motif is associated with galactose specificity [

40]. These three-amino-acid motifs differ in the hydrogen donor/acceptor pair at the first and third positions (Glu/Gln and Asn/Asp), leading to a difference in the orientations of the hydroxy groups at the 2- and 3-positions of the bound monosaccharides, discriminating between mannose and galactose.

Although this relationship between mannose/galactose specificity and the motifs applies to many C-type CRDs, different motifs have been found in invertebrate C-type CRDs [

26,

41,

42,

43,

44], suggesting the diversity of binding specificity in these lectins. For example, despite having the EPN motif (Glu113-Pro114-Asn115) in the binding site, the C-type lectin CEL-IV from the sea cucumber (

Cucumaria echinata) recognizes galactose [

45]. X-ray crystallographic analysis of CEL-IV/carbohydrate complexes revealed that the nonreducing galactose residues of melibiose and raffinose were recognized in an inverted orientation compared to mannose-binding C-type CRDs containing the EPN motif. This recognition mode was facilitated by a stacking interaction with a tryptophan residue (Trp79) (

Figure 1B). A similar contribution of tryptophan residues to the recognition of galactose is also exemplified [

46]. The significance of stacking interactions between the galactose residue and aromatic side chains was further demonstrated in the mutant of CEL-I, another

C. echinata C-type lectin [

47,

48]. Although mutations from QPD to EPN motifs were insufficient to change its binding preference from N-acetylgalactosamine to mannose, additional mutation of a tryptophan residue (Trp105), which forms the stacking interaction with the hydrophobic face of galactose, to histidine resulted in a higher affinity for mannose than GalNAc (

Figure 1C,D).

While most invertebrate C-type lectins are known to be Ca

2+-dependent, there are some lectins that exhibit Ca

2+-independent binding activity [

42,

49,

50]. For instance, the bivalve

Saxidomus purpuratus possesses two isolectins, SPL-1 and SPL-2, showing specificity for GlcNAc and GalNAc [

51], although typical C-type CRDs exhibit distinct specificities for these monosaccharides, which have different configurations of the 4-hydroxy groups. The crystal structure of the SPL-2/GalNAc complex revealed that the bound GalNAc is primarily recognized through stacking interactions with tyrosine and histidine residues, as well as hydrogen bonds with aspartate and asparagine residues. In fact, the QPD/EPN motifs are replaced by RPD (Arg-Pro-Asp) or KPD (Lys-Pro-Asp) in the subunits of SPL-1 and SPL-2, which are not directly involved in carbohydrate recognition. While Ca

2+ is not essential for carbohydrate binding, its presence can enhance the binding affinity of SPL-1 and SPL-2 by coordinating two water molecules that form hydrogen bonds with the 3- and 4-hydroxy groups of the carbohydrates. These lectins likely function in recognizing the acetamido groups present on the surface molecules of microorganisms. The diverse ligand recognition abilities of CTLDs may be achieved through structural variations in their binding sites, which are supported by the versatile fold of the C-type CRD.

4. Marine animal lectins with novel structures and carbohydrate-recognition mechanisms

4.1. Oyster lectin

CGL1 (CgDM9CP-1) is a mannose-binding lectin isolated from the Pacific oyster (

Crassostrea gigas) [

52,

53]. This lectin consists of two identical subunits of 15.5 kDa. The protomer of CGL1 consists of tandemly repeated sequences of approximately 70 amino acid residues, which exhibit homology with DM9 repeats found in the fruit fly (

Drosophila melanogaster) genome [

54]. The two carbohydrate-binding sites are located in the pockets between the two DM9 domains. This lectin possesses a unique fold with the DM9 domain structure, distinct from other known lectins [

52]. In the crystal structure of the CGL1/mannose complex (

Figure 2), the bound mannose molecules are recognized through hydrogen bonds formed between the 2-, 3-, and 4-hydroxy groups of mannose and the side chains of Asp22, Lys43, and Glu39, resulting in high specificity for terminal mannose in various oligosaccharides. This is consistent with the results obtained from frontal affinity chromatography and glycan array measurements [

52,

53]. Besides CGL1, similar DM9 domain lectins have been identified in

C. gigas, and they have been suggested to be involved in innate immunity based on their ability to bind several pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) such as lipopolysaccharide, peptidoglycan, mannan, and β-1,3-glucan [

53,

55,

56].

While DM9 domain proteins from

C. gigas have demonstrated mannose-specific lectin activity, the functions of most DM9 domain proteins from other species remain unclear. For instance, the DM9 protein from the parasitic flatworm (

Fasciola gigantica) (FgDM9-1) has been shown to possess mannose-binding ability and can agglutinate erythrocytes and bacteria [

57]. Interestingly, FgDM9-1 was found to be relocated to vesicular structures within the cell under conditions of bacterial, drug, and heat stress [

58]. A similar intracellular relocation into vesicle-like structures has been observed for another DM9 domain protein, PRS1, from the mosquito (

Anopheles gambiae) [

59]. PRS1 was induced in the epithelial cells of the salivary glands upon invasion by the malaria parasite

Plasmodium, and it was also relocated to vesicle-like structures [

59]. These findings suggest that DM9 proteins may be involved in innate immunity by interacting with mannose-containing molecules and related molecules of pathogens and parasites. In vertebrates, DM9 repeat motifs have only been identified as domains of fish venom proteins (59, 60).

4.2. Sea anemone lectin

A novel lectin named AJLec (18.5 kDa) was discovered in the cnidarian

Anthopleura japonica (sea anemone) [

62]. AJLec is a dimeric lectin composed of two identical subunits linked by two disulfide bonds, forming a helical-rod shape with lactose binding sites located at both termini. AJLec exhibits Ca

2+-dependent carbohydrate-binding activity, similar to C-type lectins. However, its amino acid sequence and tertiary structure show no resemblance to any known lectins, including C-type CRDs. In the carbohydrate-binding site (

Figure 3), one Ca

2+ ion is located, forming two coordinate bonds with the 2- and 3-hydroxy groups of the galactose residue of lactose. Binding is further stabilized by hydrogen bonds with nearby residues, including Ca

2+-coordinating ones (Glu141 and Asp150). Arg64 appears to be crucial for the recognition of galactose as it forms a hydrogen bond with the 4-axial hydroxy group of the galactose residue. This represents a significant difference in the galactose recognition mode compared to galactose-specific C-type CRDs, which form coordinate bonds and hydrogen bond networks between Ca

2+ and the 3- and 4-hydroxy groups of galactose. AJLec preferentially binds to galactose and glycoproteins with β-linked terminal galactose residues but not to N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc), which is commonly recognized by many other galactose-binding lectins. This difference is due to the involvement of a coordinate bond between the Ca

2+ ion and the 2-hydroxy group of galactose, which is replaced by an acetamido group in N-acetylgalactosamine.

Notably, genes encoding AJLec homologues are exclusively found in cnidarians, such as sea anemones and corals. This may be related to unique features in the life of these organisms. On the other hand, the dimeric structure of AJLec with carbohydrate-binding sites protruding on both sides of the molecule suggests a potential role in crosslinking carbohydrate chains on invading microorganisms, leading to their neutralization or activation of phagocytes.

5. Lectins as toxins from marine animals

Many plant lectins have the ability to induce cellular toxicity, likely due to their role in self-defense against invading organisms such as pathogenic bacteria or insects [

63,

64]. This toxicity arises from their capacity to cross-link surface carbohydrate-containing molecules on target cells, influencing the signaling pathways within those cells. Moreover, when incorporated into protein toxins, lectin domains can function as cell-binding modules to exert potent toxicity. A well-known example of a toxic lectin is ricin, which was the first discovered toxic lectin derived from the castor bean (

Ricinus communis) [

65]. Ricin consists of an A chain with N-glycosidase activity that inactivates eukaryotic ribosomes and a B chain that serves as a lectin subunit. The B chain assists in delivering the A chain to the cytosol by binding to cell surface glycans [

66,

67]. Similar toxins with enzymatic “A” subunits and receptor-binding “B” subunits (lectin subunits) are referred to as AB toxins and are also produced by various pathogenic bacteria [

68]. Another type of toxic lectin includes pore-forming proteins, which form ion -permeable pores in the target cell membrane after binding to cell surface glycans through the lectin domains. These examples demonstrate the important roles that lectins often play in the actions of protein toxins. It has also been revealed that venomous marine animals produce various toxins containing lectin domains, suggesting a close association between their carbohydrate-binding activity and their toxic actions.

5.1. Lectin from the venomous sea urchin Toxopneustes pileolus

The venom of the globiferous pedicellariae of the venomous sea urchin

T. pileolus contains several toxic proteins that exert various biological effects [

69]. Among these proteins, the galactose-specific lectin SUL-I exhibits various activities, such as chemotactic activity on guinea pig neutrophils and mitogenic activity on murine splenocytes [

70,

71]. The amino acid sequence of SUL-I indicates that it belongs to the L-rhamnose-binding lectins (RBLs), many of which have been found in fish eggs [

72]. SUL-I is composed of 284 residues (30.5 kDa) with three repetitive sequence regions, each showing similarity to CRDs of rhamnose-binding lectins (RBLs) [

73]. The three-dimensional structure of the rSUL-I/L-rhamnose complex was determined by X-ray crystallographic analysis with a resolution of 1.8 Å (

Figure 4) [

74]. The overall structure of rSUL-I consists of three distinctive CRDs, which share structural similarities with the CRDs of CSL3, the rhamnose-binding lectin from chum salmon (

Oncorhynchus keta) eggs [

75]. The bound L-rhamnose molecules are primarily recognized by rSUL-I through hydrogen bonds between their 2-, 3-, and 4-hydroxy groups and Asp, Asn, and Glu residues in the binding sites. When interactions of rSUL-I with oligosaccharides were examined, a higher affinity was observed for galactosylated (asialylated) N-glycans, suggesting that the potential target carbohydrate structures are galactose-terminated N-glycans. While the CRDs of rSUL-I adopt similar folds compared to those of CSL3, a significant difference was found around the variable loop in the carbohydrate-binding sites, which may be related to the difference in binding specificities for oligosaccharides between these lectins. SUL-I has carbohydrate-binding sites in its three domains, all oriented towards the same side of the protein. This structure could be advantageous for cross-linking specific membrane glycoproteins containing galactose-terminated carbohydrate chains, thereby triggering cellular responses.

5.2. Hemolytic lectin from the sea cucumber C. echinata

CEL-III is a galactose-specific lectin from

C. echinata, which also contains the previously mentioned C-type lectins CEL-I and CEL-IV. Although CEL-III shows Ca

2+-dependent carbohydrate binding, it belongs to the R (ricin)-type lectin family, characterized by two β-trefoil folds [

76]. Interestingly, it exhibits strong hemolytic activity and cytotoxicity [

77]. Hemolysis induced by this lectin is prominent in the alkaline region above pH 7 in the presence of Ca

2+ and can be inhibited by galactose and carbohydrates containing galactose at non-reducing ends. These observations suggest that the Ca

2+-dependent galactose binding ability is a prerequisite for its hemolytic action. CEL-III mediates hemolysis by forming pores in the target erythrocytes, relying on its galactose-specific lectin activity. Structural analyses of CEL-III have revealed that it consists of two R-type lectin domains (domains 1 and 2) in the N-terminal two-thirds and a C-terminal one-third with a β-sheet-rich novel domain (domain 3) (

Figure 5) [

78,

79]. Domain 1 contains two carbohydrate-binding sites, while domain 2 contains three. The binding of galactose-related carbohydrates is mediated by coordinate bonds with Ca

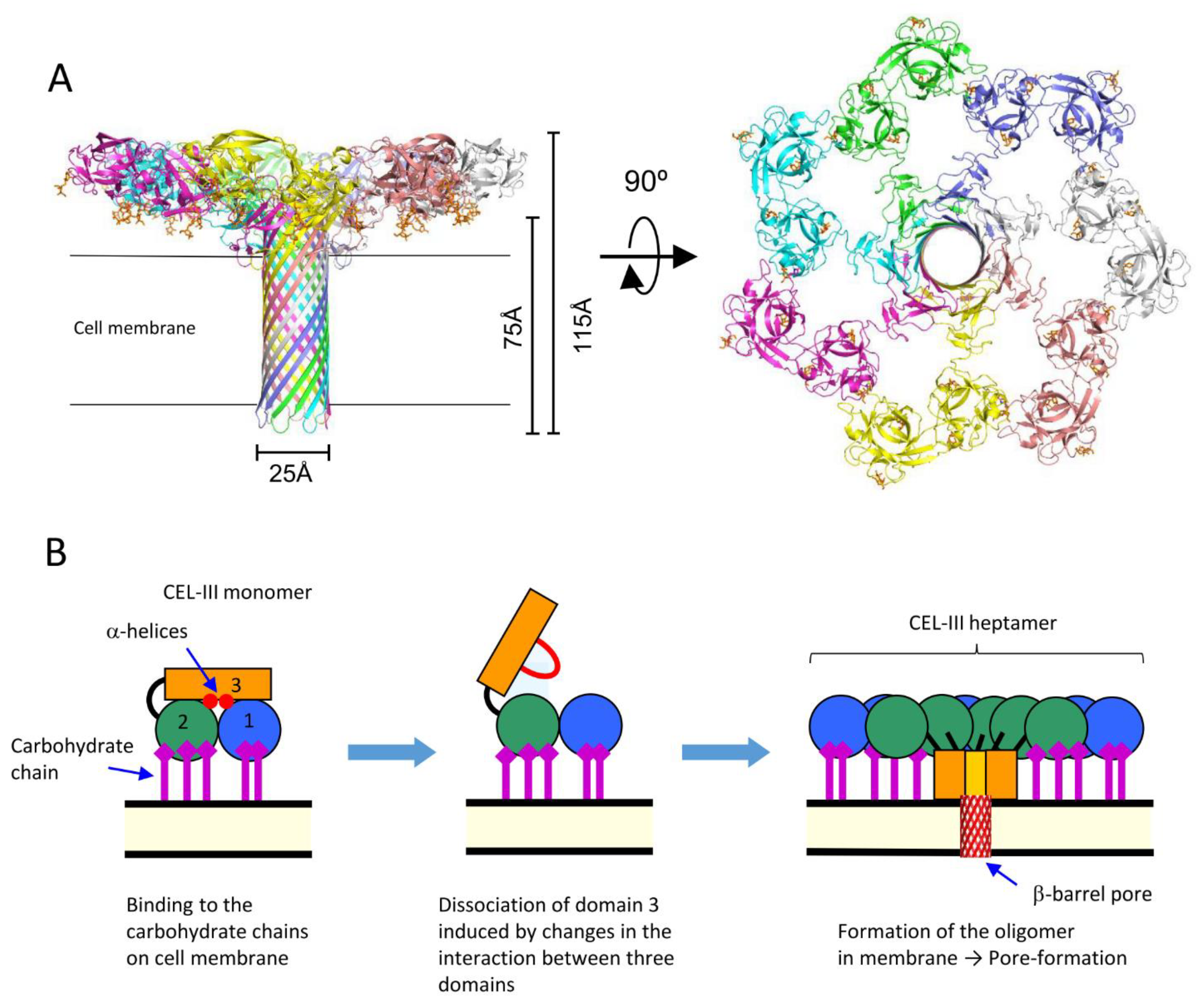

2+ ions bound in the carbohydrate-binding sites, along with hydrogen bond networks involving nearby amino acid residues. This mechanism shares similarities with the carbohydrate-recognition mechanism of C-type CRDs, despite the lack of homology in the amino acid sequences between CEL-III and C-type CRDs.

The crystal structure of the soluble oligomer of CEL-III, induced by the binding of lactulose, a galactose-containing disaccharide, revealed that CEL-III heptamerizes upon binding to galactose-containing carbohydrates (

Figure 6). This binding leads to the formation of a β-barrel structure (25 Å) composed of the C-terminal β-sheet-rich domain [

79]. When these conformational changes occur on the target cell surface, the β-barrel forms a membrane pore, allowing the passage of small molecules and ions across the cell membrane. This drastic change in the tertiary structure of domain 3 from a soluble form to a membrane-penetrating β-barrel is driven by the formation of numerous hydrogen bonds within the β-barrel and hydrophobic interactions between the hydrophobic face of the β-barrel and the nonpolar interior of the membrane.

Oligomerization of CEL-III can be triggered by β-galactoside-containing disaccharides, including lactose (Galβ1-4Glc), lactulose (Galβ1-4Fru), and N-acetyllactosamine (Galβ1-4GlcNAc), but not by galactose, N-acetylgalactosamine, and melibiose (Galα1-6Glc) [

80]. This suggests that heptamerization of CEL-III on the target cell surface is induced by cell surface receptors containing β-galactoside linkages, particularly glycosphingolipids such as lactosyl ceramide, which has been demonstrated to be an effective receptor for membrane pore formation in artificial lipid vesicles [

81]. It appears that the drastic conformational change of CEL-III is triggered by the structural changes in the binding of the specific carbohydrate into domains 1 and 2, which are then transmitted to domain 3, leading to the opening of the interface with domain 3 [

79].

The presence of β-trefoil fold domains containing QXW motifs [

82] has been observed in a wide range of proteins, including lectins, toxins, carbohydrate-related enzymes, and immune cell surface receptors, which function as carbohydrate-binding modules. Structural analysis of the hemolytic lectin LSL, isolated from the mushroom

Laetiporus sulphureus, has revealed that it also comprises an N-terminal carbohydrate-binding domain with a β-trefoil fold and a C-terminal pore-forming domain [

83]. Notably, the pore-forming domain of this lectin exhibits remarkable structural similarity to those found in pore-forming toxins of pathogenic bacteria such as

Aeromonas hydrophila and

Clostridium perfringens [

84]. Based on these findings, it can be inferred that LSL, similar to CEL-III, exhibits hemolytic activity by binding to cell surface glycans through its carbohydrate-binding domain and subsequently inserting a pore-forming domain into the cell membrane. Although the pore-forming domain of LSL does not share structural similarity with domain 3 of CEL-III, both domains are characterized by elongated β-sheets, which likely contribute to a favorable structure for penetrating the cell membrane.

5.3. Fish spine toxins containing lectin-like domains

Some fish species possess stinging spines that contain protein toxins. Among them, a toxin called natterin has been isolated from the spines of

Thalassophryne nattereri [

60]. Additionally, a homologous protein Ij-natterin has been found to be expressed in the spine venom of

Inimicus japonicus [

51]. Natterin and Ij-natterin consist of an N-terminal lectin domain, which is homologous to the oyster lectin CGL1 (DM9 domain protein) [

52], and a C-terminal aerolysin-like pore-forming domain (

Figure 7A). Although the specific carbohydrate-binding activity of the lectin domain has not been reported to date, its amino acid sequence similarity with CGL1 suggests that it may have mannose-specific lectin activity.

Proteins that have C-terminal domains homologous to those of natterin, called natterin-like proteins, are also widely distributed in fish skin [

85,

86]. The crystal structure of Dln1, one of the natterin-like proteins from zebrafish (

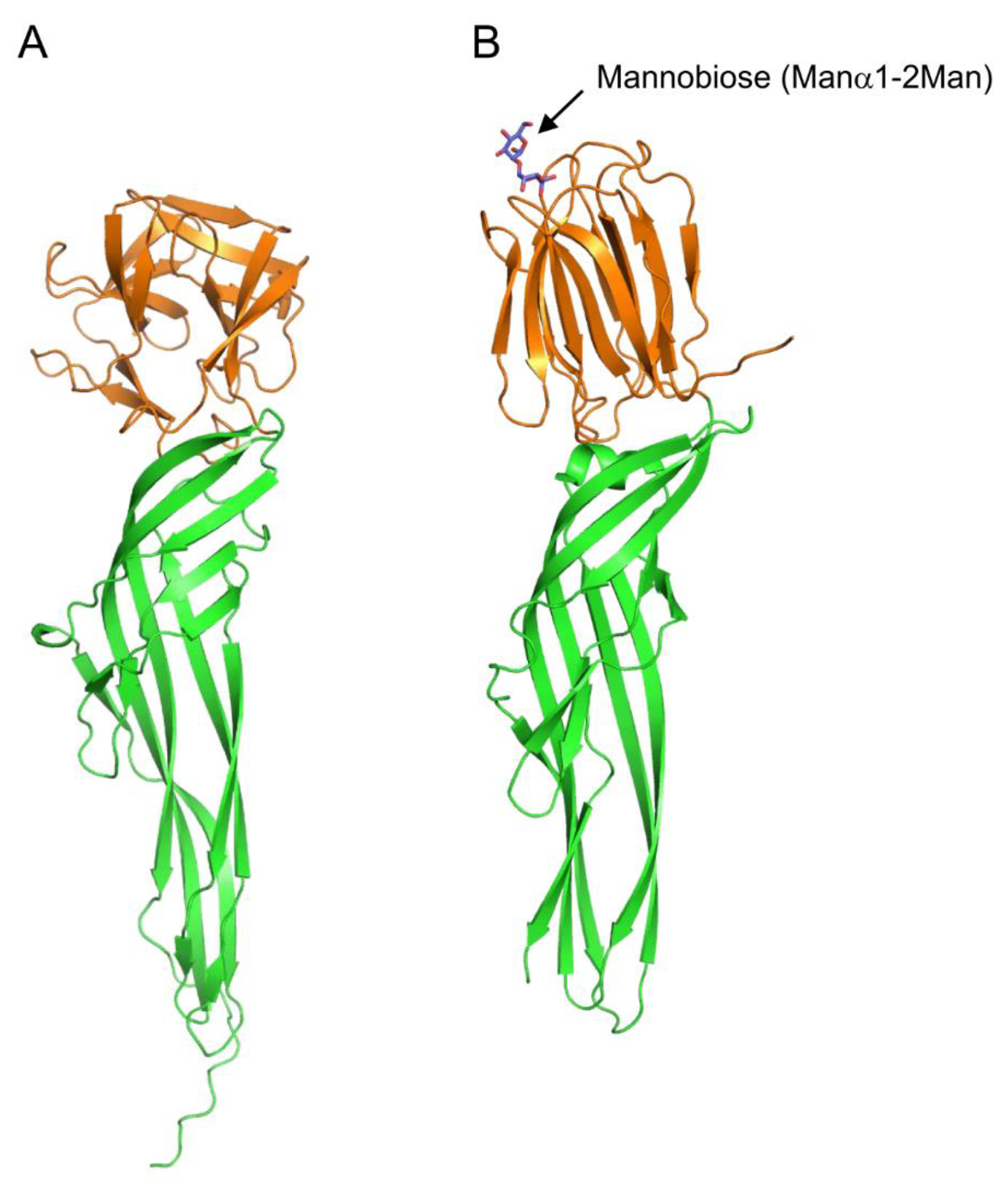

Danio rerio), revealed that Dln1 consists of an N-terminal jacalin-like lectin domain and a C-terminal aerolysin-like domain (

Figure 7B) [

87]. The lectin domain was found to bind mannobiose (Manα1-2Man and Manα1-3Man), indicating that Dln1 exhibits an affinity for high-mannose glycans. Furthermore, electron microscopic analysis revealed that upon binding to high-mannose glycans Dln1 undergoes significant conformational changes, leading to the formation of octameric pores in the lipid membrane.

Although natterin and natterin-like proteins possess C-terminal aerolysin-like domains in common, they differ in N-terminal lectin domains; the former shows a CGL1-like DM9 domain fold, while the latter has a jacalin-like domain. Considering the large conformational change during the pore-forming process of Dln1, it seems highly likely that natterin (and Ij-natterin) also induce significant conformational changes upon binding to target cell surface glycans, leading to oligomerization and pore formation. Similar large conformational changes after binding to cell surface carbohydrate chains are also observed in the course of pore formation by the hemolytic lectin CEL-III (

Figure 6B). The lectin domains of these pore-forming proteins not only play roles in binding to specific carbohydrate chains on the target cell but also trigger subsequent conformational changes leading to the formation of oligomers with transmembrane pores.

6. Conclusions

Lectins, initially discovered as hemagglutinins in plant seeds, have been found to be widely distributed in living organisms and play crucial roles in molecular and cellular recognition through carbohydrate chains. In this review, our primary focus has been on lectins from marine animals, which exhibit novel structures and functions. Marine animals, especially invertebrates, demonstrate a higher degree of diversity compared to higher vertebrates. Therefore, exploring novel proteins with unknown structures and functions among these organisms, including lectins, is expected to yield valuable information. An increasing number of studies have highlighted the crucial roles of lectins in immune systems. Lectins are particularly important in innate immunity as PRMs, enabling the recognition of foreign substances. Since information on the innate immune systems of marine invertebrates has been limited thus far, investigating lectins involved in the innate immunity of these animals is highly likely to provide valuable insights into the innate immune systems of marine animals.

Additionally, lectins that act as binding modules for various protein toxins are intriguing targets for understanding biological defense systems as well as the mechanisms of protein-carbohydrate and protein-lipid membrane interactions. Numerous pore-forming proteins containing lectin domains, including those found in marine animals, have been identified. In these pore-forming proteins, lectin domains not only serve as binding modules to target specific cells but also trigger subsequent conformational changes that lead to oligomerization and the formation of membrane-penetrating pore structures. In addition to their role as toxins, pore-forming proteins are involved in various functions in organisms, such as immune systems [

88] and apoptosis [

89]. Examining the structural changes of pore-forming lectins during the oligomerization process may provide important clues for understanding the conformational changes triggered by receptor binding.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Organization for Marine Science and Technology, Nagasaki University, and Nagasaki University Grant for Co-creation Research.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Sharon, N.; Lis, H. History of Lectins: From Hemagglutinins to Biological Recognition Molecules. Glycobiology 2004, 14, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltner, H.; Gabius, H.J. Sensing Glycans as Biochemical Messages by Tissue Lectins: The Sugar Code at Work in Vascular Biology. Thromb. Haemost. 2019, 119, 517–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilpatrick, D.C. Animal Lectins: A Historical Introduction and Overview. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Gen. Subj. 2002, 1572, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabius, H.J. Animal Lectins. Eur. J. Biochem. 1997, 243, 543–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leffler, H.; Carlsson, S.; Hedlund, M.; Qian, Y.; Poirier, F. Introduction to Galectins. Glycoconj. J. 2002, 19, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelensky, A.N.; Gready, J.E. The C-Type Lectin-like Domain Superfamily. FEBS J. 2005, 272, 6179–6217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modenutti, C.P.; Capurro, J.I.B.; Di Lella, S.; Martí, M.A. The Structural Biology of Galectin-Ligand Recognition: Current Advances in Modeling Tools, Protein Engineering, and Inhibitor Design. Front. Chem. 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drickamer, K. Two Distinct Classes of Carbohydrate-Recognition Domains in Animal Lectins. J. Biol. Chem. 1988, 263, 9557–9560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drickamer, K. C-Type Lectin-like Domains. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1999, 9, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weis, W.I.; Taylor, M.E.; Drickamer, K. The C-Type Lectin Superfamily in the Immune System. Immunol. Rev. 1998, 163, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.D.; Willment, J.A.; Whitehead, L. C-Type Lectins in Immunity and Homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 18, 374–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambi, A.; Koopman, M.; Figdor, C.G. How C-Type Lectins Detect Pathogens. Cell. Microbiol. 2005, 7, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuribara, T.; Usui, R.; Totani, K. Glycan Structure-Based Perspectives on the Entry and Release of Glycoproteins in the Calnexin/Calreticulin Cycle. Carbohydr. Res. 2021, 502, 108273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozlov, G.; Gehring, K. Calnexin Cycle – Structural Features of the ER Chaperone System. FEBS J. 2020, 287, 4322–4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahms, N.M.; Hancock, M.K. P-Type Lectins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Gen. Subj. 2002, 1572, 317–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crocker, P.R.; Paulson, J.C.; Varki, A. Siglecs and Their Roles in the Immune System. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 7, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, S.; Paulson, J.C. Siglecs as Immune Cell Checkpoints in Disease. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 38, 365–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murugesan, G.; Weigle, B.; Crocker, P.R. Siglec and Anti-Siglec Therapies. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2021, 62, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Song, X.; Wang, L.; Song, L. Pathogen-Derived Carbohydrate Recognition in Molluscs Immune Defense. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weis, W.I.; Kahn, R.; Fourme, R.; Drickamer, K.; Hendrickson, W.A. Structure of the Calcium-Dependent Lectin Domain from a Rat Mannose-Binding Protein Determined by MAD Phasing. Science (80-. ). 1991, 254, 1608–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilpatrick, D.C. Mannan-Binding Lectin: Clinical Significance and Applications. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Gen. Subj. 2002, 1572, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świerzko, A.S.; Cedzyński, M. The Influence of the Lectin Pathway of Complement Activation on Infections of the Respiratory System. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjaer, T.R.; Le, L.T.M.; Pedersen, J.S.; Sander, B.; Golas, M.M.; Jensenius, J.C.; Andersen, G.R.; Thiel, S. Structural Insights into the Initiating Complex of the Lectin Pathway of Complement Activation. Structure 2015, 23, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Teh, C.; Kishore, U.; Reid, K.B.M. Collectins and Ficolins: Sugar Pattern Recognition Molecules of the Mammalian Innate Immune System. Nefrol. Biophys. Acta 2002, 1572, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Fresno, C.; Iborra, S.; Saz-Leal, P.; Martínez-López, M.; Sancho, D. Flexible Signaling of Myeloid C-Type Lectin Receptors in Immunity and Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Yang, C.; Liu, R.; Xu, J.; Jia, Z.; Song, L. The Sequence Variation and Functional Differentiation of CRDs in a Scallop Multiple CRDs Containing Lectin. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2017, 67, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Huang, M.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L.L.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.L.; Qiu, L.; Song, L. CfLec-3 from Scallop: An Entrance to Non-Self Recognition Mechanism of Invertebrate C-Type Lectin. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, X.; You, M.; Rao, X.J.; Yu, X.Q. Insect C-Type Lectins in Innate Immunity. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2018, 83, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Melo, A.A.; Carneiro, R.F.; de Melo Silva, W.; Moura, R.d.M.; Silva, G.C.; de Sousa, O.V.; de Sousa Saboya, J.P.; do Nascimento, K.S.; Saker-Sampaio, S.; Nagano, C.S.; et al. HGA-2, a Novel Galactoside-Binding Lectin from the Sea Cucumber Holothuria Grisea Binds to Bacterial Cells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014, 64, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvennefors, E.C.E.; Leggat, W.; Hoegh-Guldberg, O.; Degnan, B.M.; Barnes, A.C. An Ancient and Variable Mannose-Binding Lectin from the Coral Acropora Millepora Binds Both Pathogens and Symbionts. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2008, 32, 1582–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Runsaeng, P.; Puengyam, P.; Utarabhand, P. A Mannose-Specific C-Type Lectin from Fenneropenaeus Merguiensis Exhibited Antimicrobial Activity to Mediate Shrimp Innate Immunity. Mol. Immunol. 2017, 92, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tetreau, G.; Pinaud, S.; Portet, A.; Galinier, R.; Gourbal, B.; Duval, D. Specific Pathogen Recognition by Multiple Innate Immune Sensors in an Invertebrate. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.-W.; Gao, J.; Xu, Y.-H.; Xu, J.-D.; Fan, Z.-X.; Zhao, X.-F.; Wang, J.-X. Novel Pattern Recognition Receptor Protects Shrimp by Preventing Bacterial Colonization and Promoting Phagocytosis. J. Immunol. 2017, 198, 3045–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Zhang, D.; Li, F.; Wang, M.; Huang, M.; Zhang, H.; Song, L. A Novel C-Type Lectin from Crab Eriocheir Sinensis Functions as Pattern Recognition Receptor Enhancing Cellular Encapsulation. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2013, 34, 832–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.W.; Xu, W.T.; Wang, X.W.; Mu, Y.; Zhao, X.F.; Yu, X.Q.; Wang, J.X. A Novel C-Type Lectin with Two CRD Domains from Chinese Shrimp Fenneropenaeus Chinensis Functions as a Pattern Recognition Protein. Mol. Immunol. 2009, 46, 1626–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Huang, M.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Qiu, L.; Song, L. CfLec-3 from Scallop: An Entrance to Non-Self Recognition Mechanism of Invertebrate C-Type Lectin OPEN. Nat. Publ. Gr. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Li, L.; Guo, X.; Litman, G.W.; Dishaw, L.J.; Zhang, G. Massive Expansion and Functional Divergence of Innate Immune Genes in a Protostome. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pees, B.; Yang, W.; Zárate-Potes, A.; Schulenburg, H.; Dierking, K. High Innate Immune Specificity through Diversified C-Type Lectin-like Domain Proteins in Invertebrates. J. Innate Immun. 2016, 8, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saco, A.; Suárez, H.; Novoa, B.; Figueras, A. A Genomic and Transcriptomic Analysis of the C-Type Lectin Gene Family Reveals Highly Expanded and Diversified Repertoires in Bivalves. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drickamer, K. Engineering Galactose-Binding Activity into a C-Type Mannose-Binding Protein. Nature 1992, 360, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Qiu, L.; Wang, H.; Song, L. C-Type Lectin in Chlamys Farreri (CfLec-1) Mediating Immune Recognition and Opsonization. PLoS One 2011, 6, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Z.; Shao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Bao, Y.; Li, C. Novel Ca2+-Independent C-Type Lectin Involved in Immune Defense of the Razor Clam Sinonovacula Constricta. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019, 84, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.Y.; Ma, K.Y.; Bai, Z.Y.; Li, J. Le Molecular Cloning and Characterization of Perlucin from the Freshwater Pearl Mussel, Hyriopsis Cumingii. Gene 2013, 526, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Song, X.; Wang, L.; Kong, P.; Yang, J.; Liu, L.; Qiu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Qiu, L.; Song, L. AiCTL-6, a Novel C-Type Lectin from Bay Scallop Argopecten Irradians with a Long C-Type Lectin-like Domain. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2011, 30, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatakeyama, T.; Kamiya, T.; Kusunoki, M.; Nakamura-Tsuruta, S.; Hirabayashi, J.; Goda, S.; Unno, H. Galactose Recognition by a Tetrameric C-Type Lectin, CEL-IV, Containing the EPN Carbohydrate Recognition Motif. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iobst, S.T.; Drickamer, K. Binding of Sugar Ligands to Ca2+-Dependent Animal Lectins. II. Generation of High-Affinity Galactose Binding by Site-Directed Mutagenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 15512–15519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatakeyama, T.; Ishimine, T.; Baba, T.; Kimura, M.; Unno, H.; Goda, S. Alteration of the Carbohydrate-Binding Specificity of a C-Type Lectin CEL-I Mutant with an EPN Carbohydrate-Binding Motif. Protein Pept. Lett. 2013, 20, 796–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriuchi, H.; Unno, H.; Goda, S.; Tateno, H.; Hirabayashi, J.; Hatakeyama, T. Mannose-Recognition Mutant of the Galactose/N-Acetylgalactosamine-Specific C-Type Lectin CEL-I Engineered by Site-Directed Mutagenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Gen. Subj. 2015, 1850, 1457–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unno, H.; Itakura, S.; Higuchi, S.; Goda, S.; Yamaguchi, K.; Hatakeyama, T. Novel Ca2+-Independent Carbohydrate Recognition of the C-Type Lectins, SPL-1 and SPL-2, from the Bivalve Saxidomus Purpuratus. Protein Sci. 2019, 28, 766–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Liao, K.; Shi, P.; Xu, J.; Ran, Z.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, L.; Cao, J.; Yan, X. Involvement of a Novel Ca2+-Independent C-Type Lectin from Sinonovacula Constricta in Food Recognition and Innate Immunity. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020, 104, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unno, H.; Higuchi, S.; Goda, S.; Hatakeyama, T. Novel Carbohydrate-Recognition Mode of the Invertebrate C-Type Lectin SPL-1 from Saxidomus Purpuratus Revealed by the GlcNAc-Complex Crystal in the Presence of Ca2+. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Commun. 2020, 76, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unno, H.; Matsuyama, K.; Tsuji, Y.; Goda, S.; Hiemori, K.; Tateno, H.; Hirabayashi, J.; Hatakeyama, T. Identification, Characterization, and X-Ray Crystallographic Analysis of a Novel Type of Mannose-Specific Lectin CGL1 from the Pacific Oyster Crassostrea Gigas. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Wang, L.; Huang, M.; Jia, Z.; Weinert, T.; Warkentin, E.; Liu, C.; Song, X.; Zhang, H.; Witt, J.; et al. DM9 Domain Containing Protein Functions as a Pattern Recognition Receptor with Broad Microbial Recognition Spectrum. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponting, C.P.; Mott, R.; Bork, P.; Copley, R.R. Novel Protein Domains and Repeats in Drosophila Melanogaster: Insights into Structure, Function, and Evolution. Genome Res. 2001, 11, 1996–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, P.; Wang, W.; Dong, M.; Wang, M.; Gong, C.; Jia, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, A.; Wang, L.; et al. A DM9-Containing Protein from Oyster Crassostrea Gigas (CgDM9CP-2) Serves as a Multipotent Pattern Recognition Receptor. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2018, 84, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhao, Q.; Yuan, P.; Li, J.; Song, X.; Liu, Z.; Ding, D.; Wang, L.; Song, L. A DM9-Containing Protein from Oyster Crassostrea Gigas (CgDM9CP-3) Mediating Immune Recognition and Encapsulation. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2021, 116, 103937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phadungsil, W.; Grams, R. Agglutination Activity of Fasciola Gigantica DM9-1, a Mannose-Binding Lectin. Korean J. Parasitol. 2021, 59, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phadungsil, W.; Smooker, P.M.; Vichasri-Grams, S.; Grams, R. Characterization of a Fasciola Gigantica Protein Carrying Two DM9 Domains Reveals Cellular Relocalization Property. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2016, 205, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chertemps, T.; Mitri, C.; Perrot, S.; Sautereau, J.; Jacques, J.C.; Thiery, I.; Bourgouin, C.; Rosinski-Chupin, I. Anopheles Gambiae PRS1 Modulates Plasmodium Development at Both Midgut and Salivary Gland Steps. PLoS One 2010, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magalhães, G.S.; Lopes-Ferreira, M.; Junqueira-De-Azevedo, I.L.M.; Spencer, P.J.; Araújo, M.S.; Portaro, F.C.V.; Ma, L.; Valente, R.H.; Juliano, L.; Fox, J.W.; et al. Natterins, a New Class of Proteins with Kininogenase Activity Characterized from Thalassophryne Nattereri Fish Venom. Biochimie 2005, 87, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatakeyama, T.; Kishigawa, A.; Unno, H. Molecular Cloning and Characterization of the Two Putative Toxins Expressed in the Venom of the Devil Stinger Inimicus Japonicus. Toxicon 2021, 201, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unno, H.; Nakamura, A.; Mori, S.; Goda, S.; Yamaguchi, K.; Hiemori, K.; Tateno, H.; Hatakeyama, T. Identification, Characterization, and X-Ray Crystallographic Analysis of a Novel Type of Lectin AJLec from the Sea Anemone Anthopleura Japonica. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.E.; Drickamer, K. Mammalian Sugar-Binding Receptors: Known Functions and Unexplored Roles. FEBS J. 2019, 286, 1800–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, M.E.; Drickamer, K. Convergent and Divergent Mechanisms of Sugar Recognition across Kingdoms. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2014, 28, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsnes, S. The History of Ricin, Abrin and Related Toxins. Toxicon 2004, 44, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, J.M.; Roberts, L.M.; Robertus, J.D. Ricin: Structure, Mode of Action, and Some Current Applications. FASEB J. 1994, 8, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, M.R.; Lord, J.M. Cytotoxic Ribosome-Inactivating Lectins from Plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Proteins Proteomics 2004, 1701, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odumosu, O.; Nicholas, D.; Yano, H.; Langridge, W. AB Toxins: A Paradigm Switch from Deadly to Desirable. Toxins (Basel). 2010, 2, 1612–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.A.; Abe, J.; Siddiq, A.; Nakagawa, H.; Honda, S.; Wada, T.; Ichida, S. UT841 Purified from Sea Urchin (Toxopneustes Pileolus) Venom Inhibits Time-Dependent 45Ca2+ Uptake in Crude Synaptosome Fraction from Chick Brain. Toxicon 2001, 39, 1223–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, H. , Hashimoto, T., Hayashi, H., Shinohara, M., Ohura, K., Tachikawa, E. Isolation of a Novel Lectin from the Globiferous Pedicellariae of the Sea Urchin Toxopneustes Pileolus. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1996, 391, 213–223. [Google Scholar]

- Takei, M.; Nakagawa, H. A Sea Urchin Lectin, SUL-1, from the Toxopneustid Sea Urchin Induces DC Maturation from Human Monocyte and Drives Th1 Polarization in Vitro. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2006, 213, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tateno, H. SUEL-Related Lectins, a Lectin Family Widely Distributed throughout Organisms. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2010, 74, 1141–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatakeyama, T.; Ichise, A.; Yonekura, T.; Unno, H.; Goda, S.; Nakagawa, H. CDNA Cloning and Characterization of a Rhamnose-Binding Lectin SUL-I from the Toxopneustid Sea Urchin Toxopneustes Pileolus Venom. Toxicon 2015, 94, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatakeyama, T.; Ichise, A.; Unno, H.; Goda, S.; Oda, T.; Tateno, H.; Hirabayashi, J.; Sakai, H.; Nakagawa, H. Carbohydrate Recognition by the Rhamnose-Binding Lectin SUL-I with a Novel Three-Domain Structure Isolated from the Venom of Globiferous Pedicellariae of the Flower Sea Urchin Toxopneustes Pileolus. Protein Sci. 2017, 26, 1574–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirai, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Lee, M. sub; Ogawa, T.; Muramoto, K. Structure of Rhamnose-Binding Lectin CSL3: Unique Pseudo-Tetrameric Architecture of a Pattern Recognition Protein. J. Mol. Biol. 2009, 391, 390–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatakeyama, T.; Unno, H.; Kouzuma, Y.; Uchida, T.; Eto, S.; Hidemura, H.; Kato, N.; Yonekura, M.; Kusunoki, M. C-Type Lectin-like Carbohydrate Recognition of the Hemolytic Lectin CEL-III Containing Ricin-Type β-Trefoil Folds. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 37826–37835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatakeyama, T.; Kohzaki, H.; Nagatomo, H.; Yamasaki, N. Purification and Characterization of Four Ca2+-Dependent Lectins from the Marine Invertebrate, Cucumaria Echinata. J. Biochem. 1994, 116, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, M.; Tabata, S.; Sugihara, K.; Kouzuma, Y.; Kimura, M.; Yamasaki, N. Primary Structure of Hemolytic Lectin CEL-III from Marine Invertebrate Cucumaria Echinata and Its CDNA: Structural Similarity to the B-Chain from Plant Lectin, Ricin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Protein Struct. Mol. Enzymol. 1999, 1435, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unno, H.; Goda, S.; Hatakeyama, T. Hemolytic Lectin CEL-III Heptamerizes via a Large Structural Transition from a-Helices to a b-Barrel during the Transmembrane Pore Formation Process. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 12805–12812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatakeyama, T.; Furukawa, M.; Nagatomo, H.; Yamasaki, N.; Mori, T. Oligomerization of the Hemolytic Lectin CEL-III from the Marine Invertebrate Cucumaria Echinata Induced by the Binding of Carbohydrate Ligands. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 16915–16920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatakeyama, T.; Sato, T.; Taira, E.; Kuwahara, H.; Niidome, T.; Aoyagi, H. Characterization of the Interaction of Hemolytic Lectin CEL-III from the Marine Invertebrate, Cucumaria Echinata, with Artificial Lipid Membranes: Involvement of Neutral Sphingoglycolipids in the Pore-Forming Process. J. Biochem. 1999, 125, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazes The Qxw Motif: A Flexilble Lectin Fold. Protein Sci. 1996, 5, 1490–1501.

- Mancheño, J.M.; Tateno, H.; Goldstein, I.J.; Martínez-Ripoll, M.; Hermoso, J.A. Structural Analysis of the Laetiporus Sulphureus Hemolytic Pore-Forming Lectin in Complex with Sugars. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 17251–17259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podobnik, M.; Kisovec, M.; Anderluh, G. Molecular Mechanism of Pore Formation by Aerolysin-like Proteins. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2017, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, B.; Patel, D.M.; Kitani, Y.; Viswanath, K.; Brinchmann, M.F. Novel Mannose Binding Natterin-like Protein in the Skin Mucus of Atlantic Cod (Gadus Morhua). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2017, 68, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, C.; Disner, G.R.; Alice, M.; Falc, P.; Seni-silva, A.C.; Luis, A.; Maleski, A.; Souza, M.M.; Cristina, M.; Tonello, R.; et al. Structure , and Immune Function. 2021.

- Jia, N.; Liu, N.; Cheng, W.; Jiang, Y.; Sun, H.; Chen, L.; Peng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Structural Basis for Receptor Recognition and Pore Formation of a Zebrafish Aerolysin-like Protein. EMBO Rep. 2016, 17, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosado, C.J.; Kondos, S.; Bull, T.E.; Kuiper, M.J.; Law, R.H.P.; Buckle, A.M.; Voskoboinik, I.; Bird, P.I.; Trapani, J.A.; Whisstock, J.C.; et al. The MACPF/CDC Family of Pore-Forming Toxins. Cell. Microbiol. 2008, 10, 1765–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarado-Mesén, J.; Solano-Campos, F.; Canet, L.; Pedrera, L.; Hervis, Y.P.; Soto, C.; Borbón, H.; Lanio, M.E.; Lomonte, B.; Valle, A.; et al. Cloning, Purification and Characterization of Nigrelysin, a Novel Actinoporin from the Sea Anemone Anthopleura Nigrescens. Biochimie 2019, 156, 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly Accurate Protein Structure Prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).