1. Introduction

Approximately 61% of the 357 extant turtle species [

1] are endangered or extinct [

2]. Among them, reptiles such as turtles and tortoises reportedly face more serious extinction risks than other vertebrates [

2,

3,

4,

5]. Artificial human activities are the main cause underlying the decrease in the turtle population, and the invasion of the natural ecosystems by alien species further accelerates the population decrease of existing turtles [

5].

Invasive alien species are organisms that disturb or are likely to disturb the balance of the ecosystem [

6]. In South Korea, invasive alien species are designated and managed according to the law to respond to their impact on the ecosystem. In South Korea, the genus

Trachemys spp. and five species,

Pseudemys concinna,

Mauremys sinensis,

Macrochelys temminckii,

Pseudemys nelson, and

Chelydra serpentina were designated as invasive alien species in 2001, 2020, 2020, 2021, and 2022, respectively. Most of the invasive alien turtles found in the wild were bred as pets and then abandoned or released for religious ceremonies. Among them,

Trachemys scripta was the first to be introduced to South Korea in the late 1970s for religious and pet-keeping purposes. To date, DNA barcoding analysis of eggshells has confirmed the reproduction of

T. scripta,

Pseudemys spp., and

C. serpentina, and hatchlings were found for

T. scripta and

P. concinna, indicating successful settlement ([

6,

7,

8], Koo et al. unpublished).

T. scripta is the most exported species in the United States, along with

T. scripta troostii,

G. pseudogeographic, and

P.

nelsoni [

9], with 43.6 million exports from 1989 to 1997 and 52 million exports from 1998 to 2022 [

10]. According to The Human Society of the United States (2001), more than 8.7 million

T. scripta were exported from the United States in 1997, of which

T. scripta elegans accounted for 93.2%. In the same year, South Korea was the third largest import nation after China and Hong Kong, with live turtle imports from the United States exceeding 1 million.

According to Koo et al. [

11], 677 alien amphibians and reptiles species were sold online in 2019 in South Korea being approximately 2.1 times higher than officially imported species in 2015. To date, ten invasive turtle species have been found in the native ecosystem of the Korean peninsula (

C. serpentina,

M. sinensis,

Chrysemys picta bellii,

Graptemys ouachitensis,

Graptemys pseudogeographica,

P. concinna,

P. nelsoni,

Pseudemys peninsularis,

Pseudemys rubriventris, and

T. scripta [

12]). Among these, five species (50%) are designated as invasive alien species. The prevention and control of invasive species have received considerable attention worldwide owing to both the ecological impact on native species and the economic resources spent on removal [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. Management measures for

T. scripta include elimination, public education, and the provision of suggestions on management strategies [

10,

18]. To date, only two studies on the management of invasive turtle species have been conducted in South Korea [

19,

20]. However, studies on the current status and management of invasive alien turtle species in South Korea are insufficient.

Therefore, this study aimed to identify the current domestic reuse status of T. scripta, as well as the current import status of invasive turtles in South Korea. In addition, we suggest an effective management plan for turtles, focusing on invasive alien turtle species in particular.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Distribution of T. scripta in South Korea

To confirm the distribution of

T. scripta, data from the “National Habitat Survey of Alien Species” conducted by the National Institute of Ecology (NIE) from 2014 to 2022 were analyzed. The data used in this study are stored in NIE ECObank (

http://doi.or.kr/10.22756/ASD.20220000000812) as open-source data. The survey was conducted in all cities of the Korean Peninsula (excluding Ulleung-gun). The target species included all alien organisms introduced in South Korea; in the case of alien amphibian reptiles, there were a total of 363 species (25 amphibian and 338 reptile species). Among these, the key species were invasive alien species and those with potential risks to ecosystems. Reservoirs, ecological parks, and rivers were subject to investigation, and data on all species (including species, individuals, sizes, and places of discovery) were recorded.

2.2. Turtle sales status in traditional markets

A survey was conducted from February to October 2022 in 13 traditional markets across South Korea to determine the reuse of T. scripta. The traditional markets included Cheonggyecheon (Seoul), Moran Market (Seongnam, Gyeonggi), Jayu Market (Mokpo, Jeonnam), Chilseong Market (Daegu), Seomun Market (Daegu), Gwanmun Market (Daegu), Bujeon Market (Busan), and Dongnae Market (Busan), where sales of foreign turtles have been confirmed since 2020. The species, carapace length, and price of the sold turtles were recorded.

2.3. Management status of abandoned and lost turtles

To identify cases of abandoned or lost T. scripta, cases reported by the Animal Protection Management System of the Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency from December 2019 to December 2022 were recorded. Registered turtles were classified into adoption, release, return, donation, announcement (still on resale), euthanasia, and natural death categories, of which the cases categorized as adoption, release, return, donation, and announcement were classified as reuses and converted into total percentages.

In addition, media items, such as news articles recorded after the 2000s were searched to find out the release status of alien turtles for religious purposes.

2.4. Import status of alien turtles

Since

T. scripta was designated as an invasive alien species in 2001, the import status of alien turtles was investigated from 2002 to 2022. The Ministry of Environment selected 23 items that were highly likely to be recorded when reporting imported organisms, and turtles were classified as item number (HS code) 0106203000. The item number refers to all imported turtles; thus, details on the purpose and number of turtle species could not be confirmed. Data from the Trade Statistics Service (TRASS,

https://www.bandtrass.or.kr/index.do) were used to confirm information on turtles imported into South Korea for 21 years. Data in TRASS are classified by item, country, continent, airport/port, domestic region, customs, payment method, transaction classification, and transaction type. In this study, trade by items using HS code (0106203000) statistical data were used, and the country, weight (kg), and value (

$) of turtles imported into South Korea yearly were confirmed.

2.5. Data analysis

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was performed in order to confirm the normality of the cases of abandoned and lost alien turtles; none of the variables met the normality assumptions. Therefore, an analysis of the cases of abandoned and lost alien turtles differences of each variable was performed using the Kruskal-Wallis H test, a nonparametric test. All analyses were carried out using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) [

21].

3. Results

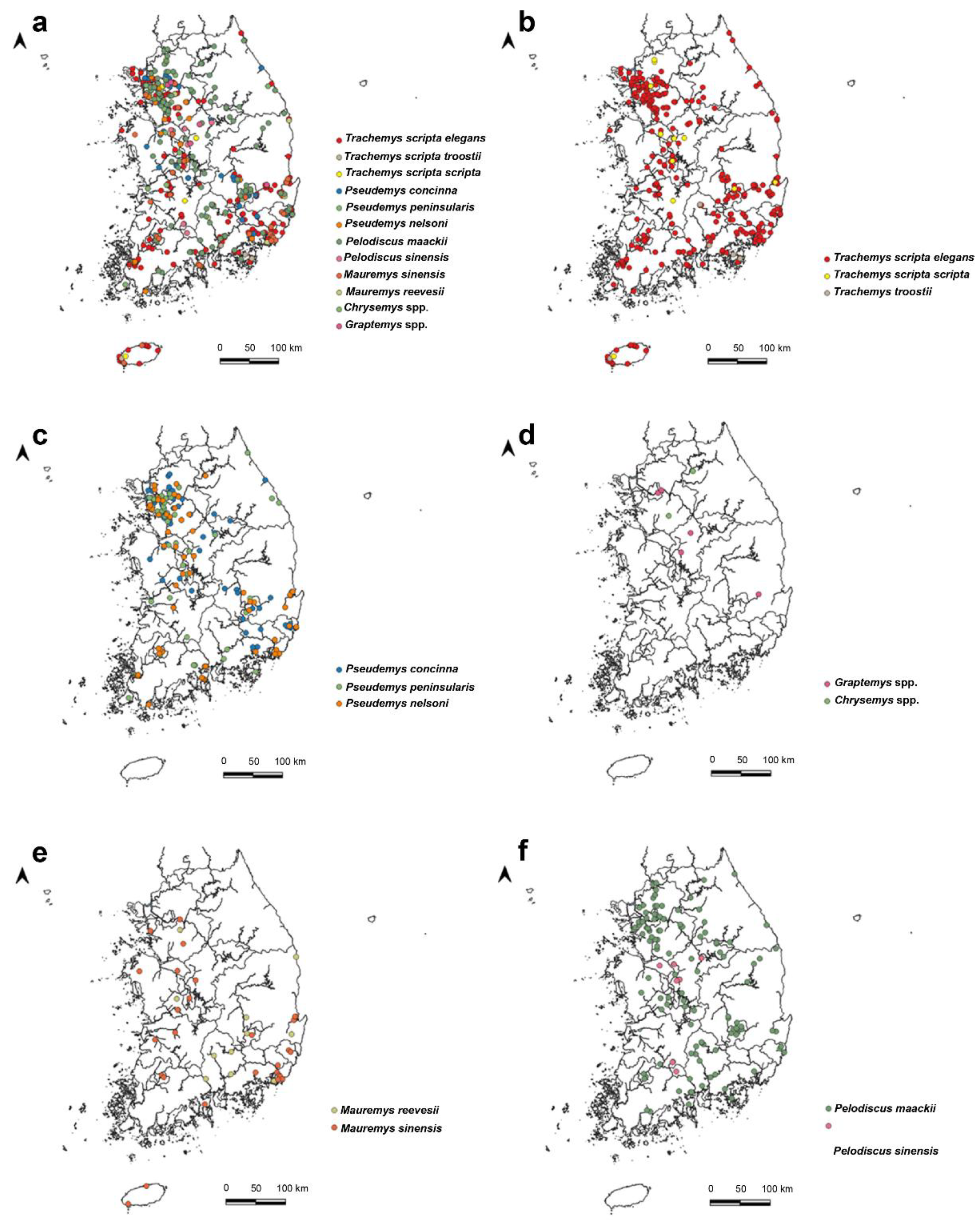

3.1. Distribution of T. scripta and other alien turtles in South Korea

For a total of nine years (2014–2022), the habitats of ten alien turtle species were confirmed at 341 points in 109 of 161 cities in South Korea. The alien turtle species identified were

T. scripta,

P. concinna,

P. nelsoni,

P. peninsularis,

M. sinensis,

C. picta picta,

C. dorsalis,

G. pseudogeographica, G. ouachitensis, and

P. sinensis. In total, 2,174 individuals from 10 species were identified (

Table 1). The distribution status of alien turtle species in South Korea is shown in

Figure 1 and

Table 1.

Among the T. scripta subspecies, T. s. elegans were overwhelmingly abundant and their habitats were widely distributed in South Korea, from artificially created urban ecological parks to reservoirs and rivers located in natural ecosystems, excluding some island areas such as Ulleungdo and Dokdo.

3.2. Sales status of turtles in traditional markets

Sales of 11 alien turtle species (T. scripta, Pseudemys concinna, P. nelsoni, P. peninsularis, M. sinensis, P. sinensis, C. picta, Sternotherus carinatus, Kinosternon subrubrum, Emydura subglobosa, and M. reevesii) were confirmed in nine traditional markets nationwide (

Table 2).

By identifying the trade status by species and focusing on invasive alien species, 69 T. scripta individuals were identified in five traditional markets; their carapace lengths ranged from 5 to 40 cm and prices ranged from $11 to $118. Fifteen P. concinna individuals were identified in five traditional markets; their carapace lengths ranged from 15 to 40 cm and prices ranged from $11 to $118, similar to those of T. scripta. Two P. nelsoni individuals were identified in one market; their carapace lengths ranged from 20 to 40 cm and prices ranged from $23 to $39. Nine M. sinensis individuals were identified in three markets; their carapace lengths ranged from 20 to 40 cm and prices ranged from $15 to $39. In addition, the trade of M. reveesii, which is designated an endangered species and natural monument, was confirmed. In the case of invasive turtles, the price was determined according to the size of the carapace length: the larger the carapace, the higher the transaction price.

3.3. Management status of abandoned and lost turtles

To understand the current status of lost turtles, freshwater turtles registered in the animal protection management system (

https://www.animal.go.kr/) for approximately three years (from December 1, 2019 to December 19, 2022), were analyzed. A total of 169 cases and 178 individuals were confirmed; 46 cases were species identified at the time of registration in the system, of which 8 cases were misidentified. Through the re-identification of turtles based on the registered photographs, the species of 142 cases were identified and 27 cases remained unidentified. The identified species were

T. scripta,

P. concinna,

P. nelsoni,

Pseudemys peninsularis,

M. sinensis,

Chrysemys spp.,

S. carinatus,

Pelomedusa subrufa,

Podocnemis unifilis,

Carettochelys insculpta,

P. maackii, and

C. serpentina (

Table 3). To determine the reuse status of all abandoned turtles, euthanasia and natural death were excluded, and adoption, release, return, donation, and announcement were identified. Of these, 84 cases were adopted by new breeders, 9 cases were re-released to the place of capture, 3 cases were returned to their breeders, 7 cases were donated, and 5 cases were under announcement. Reuse status by adoption was significantly higher than other cases with an average of 7.1 cases (χ

2=26.928,

p <0.001).

T. scripta accounted for 31% of the registered turtles; 34 cases were confirmed. Of these, T. s. elegans accounted for 26 cases, T. s. scripta accounted for 6 cases, and T. s. troostii accounted for two cases. T. s. elegans was found to be overwhelmingly abundant and was most common among all lost turtles. Twenty-nine adoptions of lost T. scripta were confirmed, including one release, two donations, and two announcements. Only 10 cases of euthanasia and 8 cases of natural death were found, confirming that 65% of the T. scripta was reused.

As a result of searching for records of turtles released for religious purposes, a total of 6 news articles were found from 2012 to 2022. The release period varied from February to December. The locations were diverse, such as large reservoirs, small ponds in ecological parks, and coastal areas, and

T. scripta,

M. sinensis, and

C. picta were identified [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. The turtles had the name and date of birth of the person who released them written on their carapace or plastron, in addition to some wish fulfillment phrases, such as university acceptance or the birth of a son.

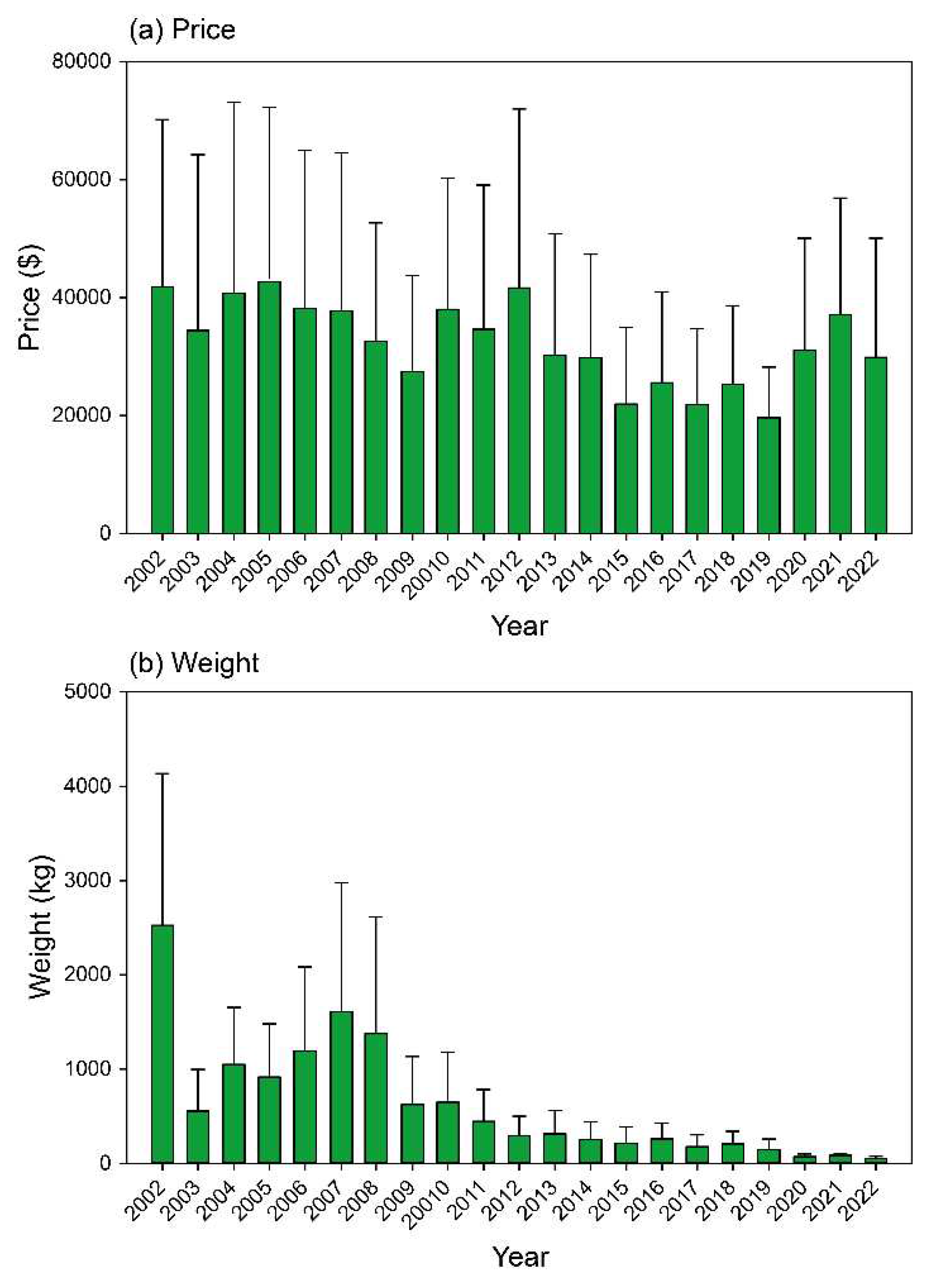

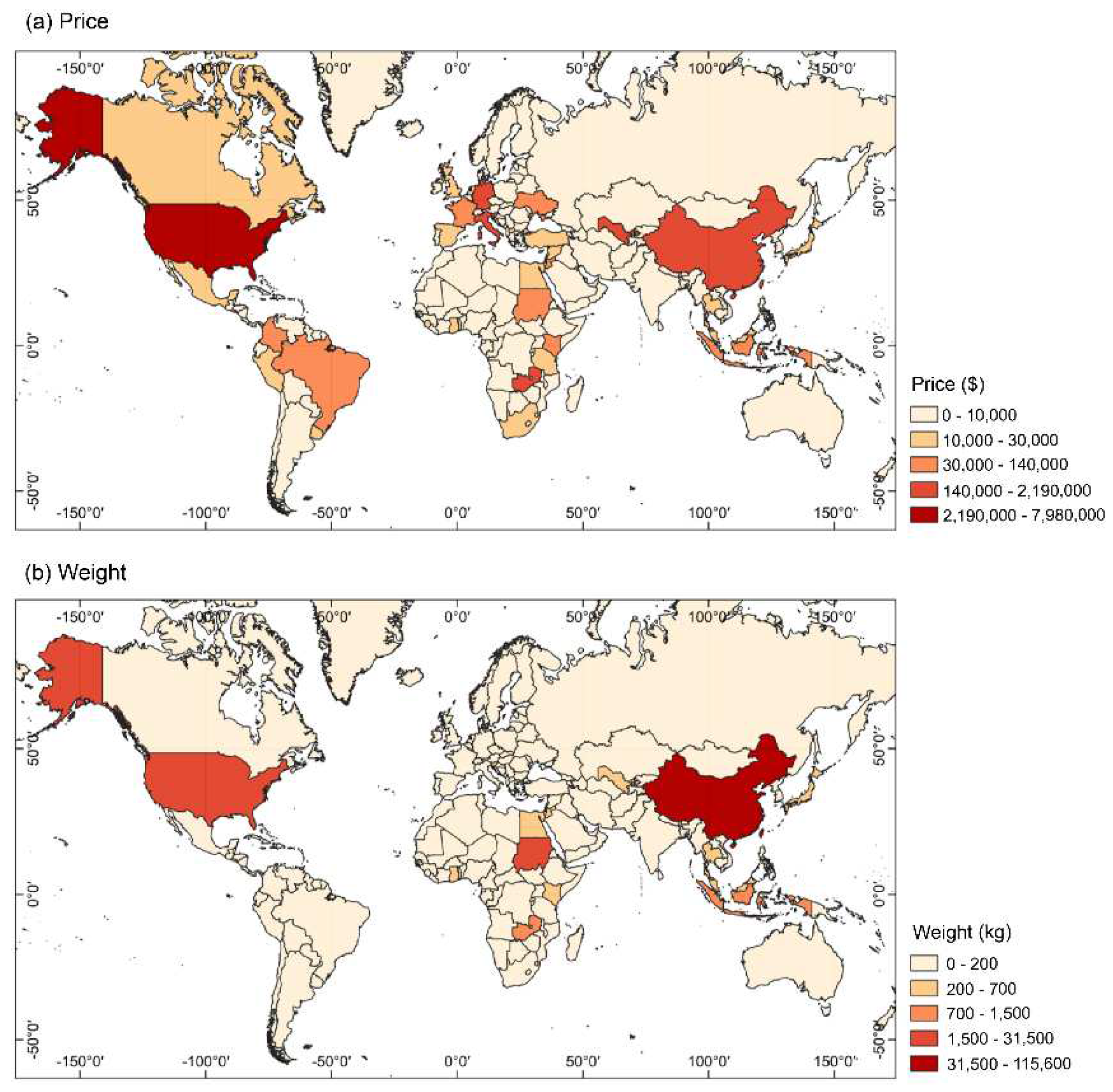

3.4. Import status of turtles for 21 years

To elucidate the import status of domestic turtles, we analyzed the import and export statistics from the Trade Statistics Service (TRASS). A total of 161,725 kg (>161 tons) and

$12,784,022 worth of turtles were imported from 63 countries over the past 21 years (2002–2022) (

Table 4). Since 2002, the overall volume of imports decreased, whereas the number of imports and countries from which the imports came steadily increased, with an average of 20 importing countries (

Table 5,

Figure 2).

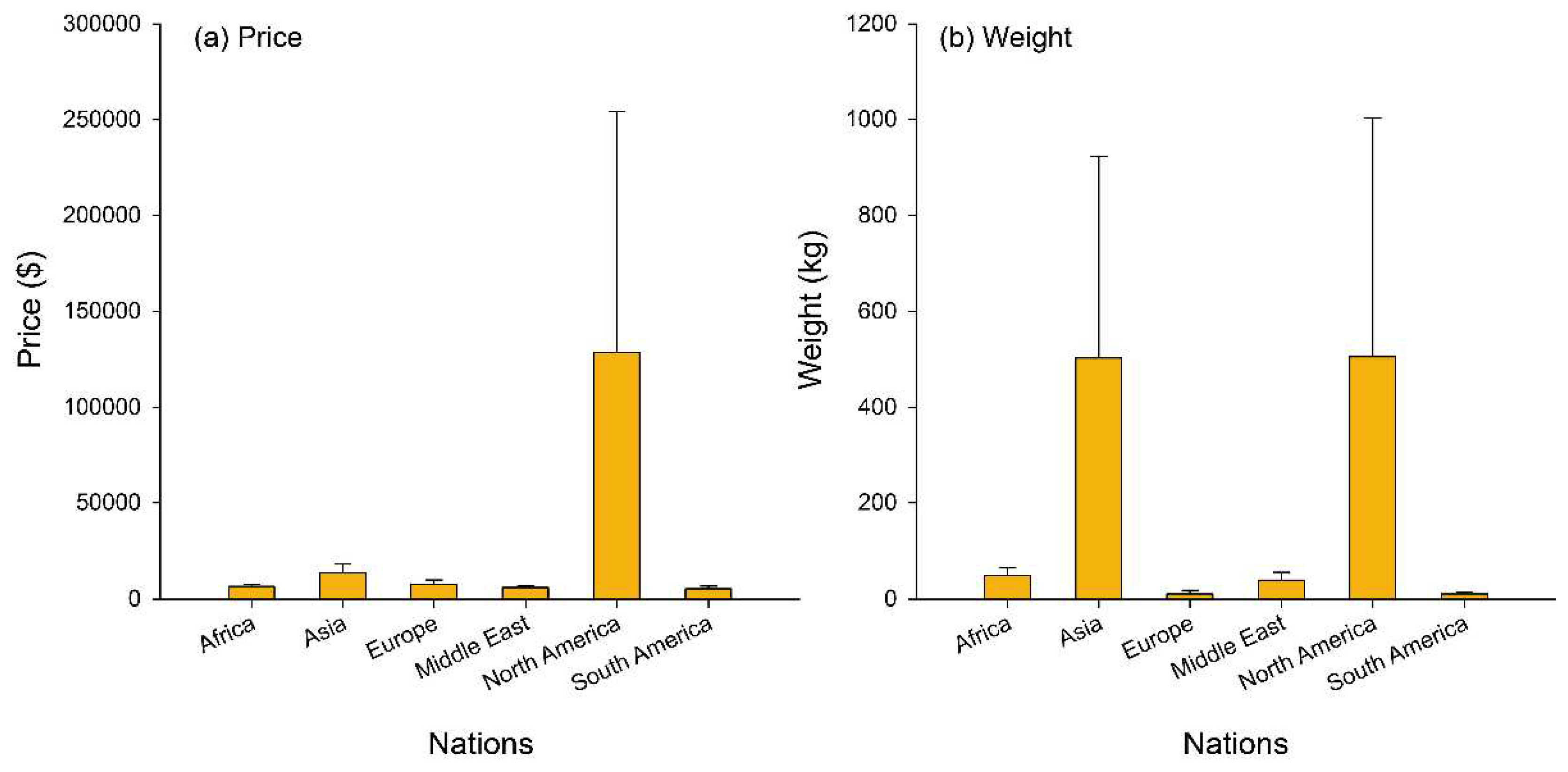

In 2016, imports were made from 36 countries (

Table 5,

Figure 2). Continental imports included Africa (16 countries), Asia (13 countries), Europe (15 countries), Central Asia (5 countries), North America (3 countries), and South America (11 countries). Asia provided the largest volume of imports, which was approximately three times higher than that of North America, whereas North America had the highest import value, which was approximately 3.5 times higher than that of Asia (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

In this study, the current status of abandoned and lost turtles in traditional markets and animal protection management systems was identified to examine the reuse status of the invasive alien species T. scripta. In addition, the domestic distribution status of alien turtles, including that of T. scripta, was determined, and the import status of turtles imported into South Korea was confirmed.

A total of 1,360

T. scripta individuals were identified in 103 cities (295 sites), which accounted for most of the discovered alien turtles.

T. scripta were mainly concentrated in metropolitan cities and, unlike other alien turtles, they were distributed across a wide area, including mountainous islands (

Figure 1). Their distribution area is wider than that of

M. reevesii and

P. maackii, which are native to South Korea. Furthermore, along with the DNA analysis to confirm the success breeding of

T. scripta we confirmed the successful establishment and spread of

T. scripta since their introduction to South Korea in 1970.

Since the

T. scripta was designated as an invasive alien species in 2001, five species of alien turtles were additionally designated as ecosystem disturbing organisms. If an alien turtle species is designated as invasive, existing breeders can apply for the “Approval of Breeding and Grace for IAS” program. However, because this program is limited to initial one-time reporting and follow-up monitoring is not compulsory, its continuous management is impossible [

19]. In addition, because the application period is limited to six months after an alien species is designated as invasive, existing breeders are often unaware of this program owing to a lack of publicity. Moreover, it was confirmed that turtles who had difficulties in breeding were abandoned in nature after they had been designated as an invasive alien species. Additionally, as application for this breeding program is only possible via mail, turtles could be abandoned owing to the hassle of registration. The abandonment of invasive turtles accounted for 61% of all alien turtles (

Table 3); after being designated as an invasive alien species, it has been revealed that the observation of the species has remarkably increased from the following year [Koo et al. unpublished].

The eradication of invasive alien species is voluntarily carried out by the Ministry of Environment, local governments, and environmental organizations. However, because there is no considerable regulation on the post-processing system, it is difficult to confirm the exact post-processing unless the Ministry of Environment independently conducts a removal event. Regarding the size of T. scripta individuals being sold in traditional markets, carapace lengths of 20–30 cm were the most common, and individuals with carapace lengths over 30 cm were also identified. Since invasive alien species cannot be reared or bred, it was discerned that T. scripta individuals were being resold in traditional markets after their capture in nature. Since the main purpose of their trade is to release them, it poses a fundamental problem, as the individuals captured in nature are traded in the market and returned to nature. Ritualized animal release is a Buddhist and Shamanistic ritual during which captive animals are released into nature to accumulate merit. These release events occur intensively each year in May on Buddha’s birthday. Since 2012, the release of turtles has become a social issue, and it has been confirmed that invasive alien turtles, such as T. scripta or M. sinensis, have been released. Abandoned freshwater turtles released in coastal areas and natural ecosystems are sometimes collected by animal rescue organizations and local governments, but since most of them are invasive alien turtles, post-processing practices other than euthanasia are practically impossible. Alternatively, there are cases in which animals are rescued by animal rescue organizations and then readopted due to misidentification. In fact, by confirming the loss of freshwater turtles from 2020 to 2022, we confirmed that T. scripta individuals rescued from Haeundae, Busan, were adopted due to misidentification. In the animal protection management system, the initial identification of these turtles was successful in 22% of cases, and the reuse rate (adoption, release, donation, and announcement) of T. scripta was 65% owing to misidentification.

Approximately 110 species of alien turtles and tortoises were imported into South Korea, and although there was no considerable difference between the number of imported species between 2015 and 2019 [

11], the number of imports decreased, and the monetary value of these imports increased considerably (

Table 5,

Figure 2). The total monetary value of these imports is inversely proportional to the trade of alien turtles for ornamental or pet-keeping purposes and is considered to reflect the desire of the public to possess increasingly rare and exotic turtles. According to Koo et al. [

11], 110 alien turtles were sold in domestic online pet shops in 2019, and their price ranged from

$6.4 to

$14,460. In addition, 47 species of turtles and tortoises corresponded to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) index, accounting for 42.7% of the total traded tortoises. Alien turtles found in the wild are inexpensive and relatively easy to purchase [

11,

12,

28] and in South Korea, alien turtles found in the natural ecosystem are large freshwater turtles with low selling prices. Among them, the observed rate of invasive alien turtles disturbing the ecosystem was remarkably high (92%), and

T. scripta turtles were the most frequently identified (66%) (

Table 1). Similar results were observed in turtles sold in traditional markets or lost owing to abandonment. In this study, it was confirmed that the types of turtles sold online vary by season and are traded in various ways, such as being sold at officially registered stores only when the quantity is received in a guerrilla way. Therefore, it is impossible to determine the exact import purpose, species, and quantity of turtles imported and distributed in South Korea, and revision of the import registration system is required to clearly identify the use and quantity of turtles.

This study confirmed that a notable number of T. scripta are adopted and reused in traditional markets. Going forward, the following should be considered: 1) To prevent the reuse of captured T. scripta and other invasive alien turtles through traditional markets and animal protection systems, the eradication project of invasive alien species should be post-processed in the form of purchases by the Ministry of Environment. 2) The accuracy of initial species identification for abandoned and lost exotic turtles should be improved and the results should be shared with research institutes and private experts to prevent missing cases. 3) In the case of additional invasive alien species designation, active publicity is required, such as actively publicizing additional designation notices of invasive alien species and distributing related brochures to each online/physical pet shop. 4) Finally, efforts should be made to reduce the rate of abandoned turtles by changing the application of existing breeders to an online, rather than postal, application system, and by extending the application period to up to one year. The current post-management strategies of invasive alien species are insufficient; therefore, the Ministry of Environment, local governments, and research institutes must cooperate to develop suitable monitoring and follow-up management plans for invasive alien species.

5. Conclusions

This study examined the domestic reuse of T. scripta from 2002 to 2022, after it had been designated an invasive alien species. The reuse of a considerable number of T. scripta and other invasive alien turtles was confirmed through the analysis of traditional markets and sales announcements of abandoned or lost animals. Thereby, the gravity and importance of invasive alien species management, after their designation as such, was revealed. To compensate for this, measures have been proposed for an efficient follow-up management system for alien turtles that have been designated and announced as invasive. The crucial information elucidated in this study could be used to guide future national policies. However, since this study could not identify the source of the T. scripta that were sold in traditional markets, it could not suggest a solution to this fundamental problem that could block supply and demand. Therefore, future research and investigations related to this issue are essential.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Hae-jun Baek; Data curation, Hae-jun Baek, Soyeon Cho, Minjeong Seok, Joo-won Shin and Dae-in Kim; Formal analysis, Soyeon Cho; Investigation, Hae-jun Baek, Joo-won Shin and Dae-in Kim; Software, Soyeon Cho; Visualization, Soyeon Cho and Joo-won Shin; Writing – original draft, Hae-jun Baek; Writing – review & editing, Hae-jun Baek, Soyeon Cho, Minjeong Seok, Joo-won Shin and Dae-in Kim. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by grants from the National Institute of Ecology funded by the Ministry of Environment of South Korea (grant numbers NIE-A-2023-08, NIE-A-2023-09, and NIE-A-2023-12).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Ecology funded by the Ministry of Environment of South Korea (grant numbers NIE-A-2023-08, NIE-A-2023-09, and NIE-A-2023-12). We would like to thank the members of the Invasive Alien Species Team at the National Institute of Ecology for helping us to carry out the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Thomson, SA. Turtles of the world: annotated checklist and atlas of taxonomy, synonymy, distribution, and conservation status. Phyllomedusa. J. Herpetol. 2021, 20, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovich JE, Ennen JR, Agha M, Gibbons JW. Where have all the turtles gone, and why does it matter? BioScience 2018, 68, 771–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanford CB, Rhodin AGJ, van Dijk PP, Horne BD, Blanck T, Goode EV, Hudson R, Mittermeier RA, Currylow A, Eisemberg C, Frankel M, Georges A, Gibbons PM, Juvik JO, Kuchling G, Luiselli L, Haitao S, Singh S, Walde A (2018) Turtles in trouble: The world’s 25+ most endangered tortoises and freshwater turtles-2018. Turtle Conservation Coalition, Hemlock Printers, Canada.

- Kraus F (2009) Alien reptiles and amphibians: a scientific compendium and analysis. Springer, Dordrecht.

- Garber SD, Burger J. A 20-yr study documenting the relationship between turtle decline and human recreation. Ecol. Appl. 1995, 5, 1151–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Ecology (2022) Monitoring of Invasive Alien Species Designated by the Act on the Conservation and Use of Biological Diversity (Ⅵ). Ministry of Environment: Seocheon, Korea, pp 61–69.

- National Institute of Ecology (2021) Investigation Ecological Risk of Alien Species. Ministry of Environment: Seocheon, Korea, pp 93–113.

- National Institute of Ecology (2019) Monitoring of Invasive Alien Species Designated by the Act on the Conservation and Use of Biological Diversity (Ⅵ). Ministry of Environment: Seocheon, Korea, pp 61–69.

- Roy HE, Rabitsch W, Scalera R (2018). Study on invasive alien species–development of risk assessments to tackle priority species and enhance prevention. Final report. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/c01568d9-025e-11e8-b8f5-01aa75ed71a1/language-en. (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- Ramsay NF, Ng PKA, O’Riordan RM, Chou LM (2007) The red-eared slider (Trachemys scripta elegans) in Asia: a review. In: Gherardi F (ed) Biological invaders in inland waters: Profiles, distribution, and threats. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 161–174.

- Koo KS, Park HR, Choi JH, Sung HC. Present status of non-native amphibians and reptiles traded in Korean online pet shop. Korean J. Environ. Ecol. 2020, 34, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo KS, Song S, Choi JH, Sung HC. Current distribution and status of non-native freshwater turtles in the wild, Republic of Korea. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin PC (2018) Managing invasive species. F1000Research, 7.

- Larson DL, Phillips-Mao L, Quiram G, Sharpe L, Stark R, Sugita S, Weiler A. A framework for sustainable invasive species management: Environmental, social, and economic objectives. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pimentel D, Zuniga R, Morrison D. Update on the environmental and economic costs associated with alien-invasive species in the United States. Ecol. Econ. 2005, 52, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine JM, Vilà M, D’Antonio CM, Dukes JS, Grigulis K, Lavorel S. Mechanisms underlying the impacts of exotic plant invasions. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2003, 270, 775–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilcove DS, Rothstein D, Dubow J, Phillips A, Losos E. Quantifying threats to imperiled species in the United States: Assessing the relative importance of habitat destruction, alien species, pollution, overexploitation, and disease. BioScience 1998, 48, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teillac-Deschamps P, Delmas V, Lorrillière R, Servais V, Cadi A, Prévot-Julliard AC (2008) Red-eared slider turtles (Trachemy scripta elegans) introduced to French urban wetlands. An integrated research and conservation program. Herpetological Conservation 3, 535–537. Available online: https://orbi.uliege.be/bitstream/2268/28797/1/TiellacCS12.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- Kim P, Yeun S, An H, Kim SH, Lee H. Breeding status and management system improvement of Pseudemys concinna and Mauremys sinensis designated as invasive alien turtles in South Korea. Ecology and Resilient Infrastructure 2020, 7, 388–395. [Google Scholar]

- Oh HS, Hong CE. Current conditions of habitat for Rana catesbeiana and Trachemys scripta elegans imported to Jeju-do, including proposed management plans. Korean J. Environ. Ecol. 2007, 21, 311–317. [Google Scholar]

- SPSS (2016) IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; Version 24.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA.

- Bang JH (2012) Who did the bad things to turtle and his shell??. 매일신문사. Available online: http://mnews.imaeil.com/page/view/2012061410461163218 (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Kim HJ (2012) ‘Poor release, it hurts me.’ Call of the Red-eared slider. Brainworld Korea. Available online: https://www.brainmedia.co.kr/BrainTraining/9197 (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Park JH (2016) Respect for life through release? Rather kill life. OhmyNews. Available online: http://www.ohmynews.com/NWS_Web/View/at_pg.aspx?CNTN_CD=A0002185995 (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Park GE (2019) Named on the turtle shell with paint and release it.?... Killing, not releasing.노컷뉴스. Available online: https://www.nocutnews.co.kr/news/5263572.

- Park YS (2020) [Camera news] Freshwater turtle abandoned in the sea with red writing on the plastron. Yonhapnews. Available online: https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20200210116400062 (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Choi HJ (2022) ‘The plastron is full of people’s name’ Why do freshwater turtles go to sea. ilyo. Available online: https://m.ilyo.co.kr/?ac=article_view&entry_id=427395 (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Masin S, Bonardi A, Padoa-Schioppa E, Bottoni L, Ficetola GF (2014) Risk of invasion by frequently traded freshwater turtles. Biol Invasions 16, 217–231. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).