1. Introduction

In recent years, women are increasingly taking advantage of opportunities in the job market because of increased levels of education and a greater necessity to supplement household income. In Sri Lanka, the employment rate for women is 92.1%, with nearly half of them (46.7%) engaged in the service sector and the rest working in industry and agriculture [

1]. However, the changed social status of women resulted in additional workload and stress resulting in adverse effects on the health and nutritional status of working women. There is increasing concern that working women may contribute to the growing burden of non-communicable diseases such as high blood pressure, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, cancer etc. [

2,

3]. In Sri Lanka, about 24% of working-age women have been suffering from various chronic diseases [

2]. Thus, malnutrition in women can significantly affect their participation in the job market and their productivity, which in turn leads to economic losses for families and societies [

4,

5]. Besides, adequate nutritional status of women is critical not only for their health but also for their children’s health and well-being [

6,

7,

8].

Previous studies have reported poor dietary patterns or unhealthy eating habits among working women [

9,

10,

11]. Poor diet patterns with a lack of a balanced diet are known to be the primary causes of malnutrition [

12]. Earlier studies in different population groups have also shown that adequate nutrition knowledge is an important factor to promote healthier eating habits [

9,

13,

14,

15]. Yet, nutrition knowledge alone may not be sufficient for healthier dietary habits and hence in addition there is a need for a positive attitude toward healthy eating [

16,

17].

To date, no studies have focused on dietary patterns and/or eating behaviours of working women in Sri Lanka. Further, there is a lack of studies on the nutrition knowledge and attitude towards healthy eating practices of working women in Sri Lanka. As mentioned earlier that a significant proportion of working women in Sri Lanka suffer from malnutrition and chronic diseases, accessing their dietary patterns and current nutrition knowledge is necessary to develop an appropriate intervention for improving their overall health and nutrition status. Hence, the present study was undertaken to assess the dietary pattern, nutrition knowledge and attitude towards healthy eating practices of working women in Western Province, Sri Lanka.

2. Subjects and Methodology

Study Design and Participants

A cross-sectional study design was utilized to collect data from 300 women aged 20-60 years, who were employed in both public and private organizations in Western Province, Sri Lanka. The working women who were pregnant and lactating were excluded from the study. The study was approved by the Ethical Review Committees of Wayamba University, Sri Lanka and Griffith University, Australia. The study was conducted from January to July 2022.

Sampling

Study participants were selected in two stages: First, both public and private sector organizations were selected from all three districts (Colombo, Gampaha and Kalutara) of Western Province using a simple random sampling technique. In the second stage, convenience sampling was applied to select an equal number (150) of participants from two sectors, with a total of 300 participants.

Data Collection

The purpose and exact nature of the study were explained to all eligible working women, and those who agreed to participate were requested to sign a consent form before including them in the study. After receiving informed consent, trained interviewers collected the data using a pre-tested structured questionnaire. The questionnaire comprised socio-demographic information, dietary pattern, nutrition-related knowledge, and attitudes.

Socio-Demographic Characteristics:

Information on age, marital status, level of education, number of family members, living status, spouse’s education level and household monthly income were collected.

Dietary Pattern:

The information on usual food consumption patterns was assessed by interviewing the participants using a 7-day food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) containing 78 food items that are commonly consumed by the Sri Lankan population. The FFQ questionnaire was adopted from the national nutrition and micronutrient survey [

18], modified and pre-tested in the study population. The food items included in the questionnaire: various grains (rice, bread and cereals and their products); roots and tubers (sweet potato, manioc and other yams, potato, jak and breadfruit); meat (chicken, beef, pork, mutton, liver and other organ meat, processed meat); fish, shellfish, dry fish and eggs; pulses (soya meat, cowpea, chickpeas, green grams, black grams, lentils); milk and milk products (milk powder and liquid milk, curd and yoghurt, ice cream, butter, cheese and ghee); vegetables (pumpkin, carrots, beans, beetroot, cabbage, brinjals, okra etc.) and seasonal green leaves; fruits (banana, papaya, guava, avocado, pineapple, oranges, mango etc.); nuts and oils, fast foods, tea and coffee, sugar-sweetened beverages, fruit juice and snacks (biscuit, cake, chocolate etc.). The FFQ was focused on the frequency of intake of selected food items only and information on the portion size was not included. Food frequency intake responses were collected days/week and time/day, then expressed as the total frequency of consumption/week (days/week X time/day).

Dietary Diversity Score (DDS):

DDS was assessed using ten food groups based on food group definitions and scoring guidelines recommended by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) for women of reproductive age [

19]. All food items included in FFQ were categorised into 10 food groups as follows: (1) grains, roots and tubers; (2) pulses; (3) nuts and seeds; (4) dairy; (5) meat, poultry and fish; (6) eggs; (7) dark green leafy vegetables; (8) vitamin A rich fruit and vegetables; (9) other vegetables and (10) other fruits. The DDS was calculated from the data on frequency intake responses collected days/week. The consumption of all food items within a food group was summed up, then divided by seven and expressed as a frequency of consumption of each food group/day. Then, consumption of a food group was given a score of “1” and non-consumption was given a score of “0”, with a maximum score of 10. The DDS was defined as the total number of food groups consumed in a day.

Anthropometric Assessment:

Height was measured with the head in Frankfort horizontal plane and barefoot, to the nearest 0.1cm using a stadiometer. Weight was measured without shoes to the nearest 0.1kg using an electronic scale. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as body weight in kg divided by height in meter square (kg/m

2). Then, the participants were classified as underweight (<18.5 kg/m

2), normal (18.5-<25.0 kg/m2), overweight (25.0-29.9 kg/m

2) and obese (

>30.0 kg/m

2) using the cut-off values recommended by WHO [

22].

Statistical Analysis:

The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS statistical software version 26 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The data were presented as frequencies and proportions for all categorical variables, and mean, standard deviations and median for continuous variables. Socio-demographic variables were divided into groups based on prior logical categories. The median value of knowledge scores was used as a cut-off to estimate the proportion of women with good knowledge (

>median value) and poor knowledge (<median value). Similarly, the median value of attitude scores was used as a cut-off to estimate the proportion of women with good attitudes (

>median value) and poor attitudes (<median value). The proportion of women meeting the minimum DDS (consumption of 5 out of 10 food groups in a day) was calculated using scoring guidelines recommended by the FAO for women of reproductive age [

19]. Pearson’s correlation test was performed to examine the association of DDS with nutritional knowledge and attitudes, and various socio-demographic variables. Backward stepwise multiple regression analysis was carried out to examine the independent association of DDS with nutritional knowledge, attitudes and selected socio-demographic variables. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant in all analyses.

3. Results

Table 1 delineates the socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants. The majority (45.7%) of the participants were aged between 31 to 40 years. Of the participants, an equal proportion had either an advanced level or diploma degree, 43% had a bachelor's degree or above, and only 16% had an ordinary level or below. Nearly 55% of the participants belong to families with four members, and nearly two-thirds (65%) were nuclear and living separately from their parents. Additionally, spouses' education level, 22.4%, 20.7%, 16.3% and 40.7% had ordinary level and below, advanced level, diploma, and bachelor’s degree and above respectively. An almost equal proportion of the participants had either a monthly income between LKR 50 000 to 100 000 (42.6%) or more than LKR 100 000 (40.5%). Based on BMI, 38% of the working women were overweight, 13% were obese and only 2.7% were underweight.

The median frequency of intake of chicken, other meat (beef, mutton, pork), organ meat, fish, shellfish, dry fish, eggs, and milk and milk products were 2, 0, 0, 5, 1, 3, 2 and 9, respectively, per week (

Table 2). Thirty-five per cent of the women had chicken, 30.6% had eggs, 69.7% had fish and 57.7% had milk and milk products at least four times in the week preceding the interview (

Table 2). The median frequency of intake of green leafy vegetables (GLV), other vegetables and fruits were 5, 10 and 10, respectively, per week (

Table 2). Two-thirds (67%) of the women consumed green leafy vegetables and 82% had fruits at least four times a week. On the other hand, 80% of the women never had other meat (beef, mutton, or pork), 90% never had liver or any other organ meat, and 23% never had milk and milk products. A large majority of the women never had shellfish (prawns, crabs, shrimps; 47%), processed meat (43%), fast food (46%), fruit juice (45%) and sugar-sweetened beverages (71%), while over 60% of women had tea and coffee with sugar 7 times or more per week.

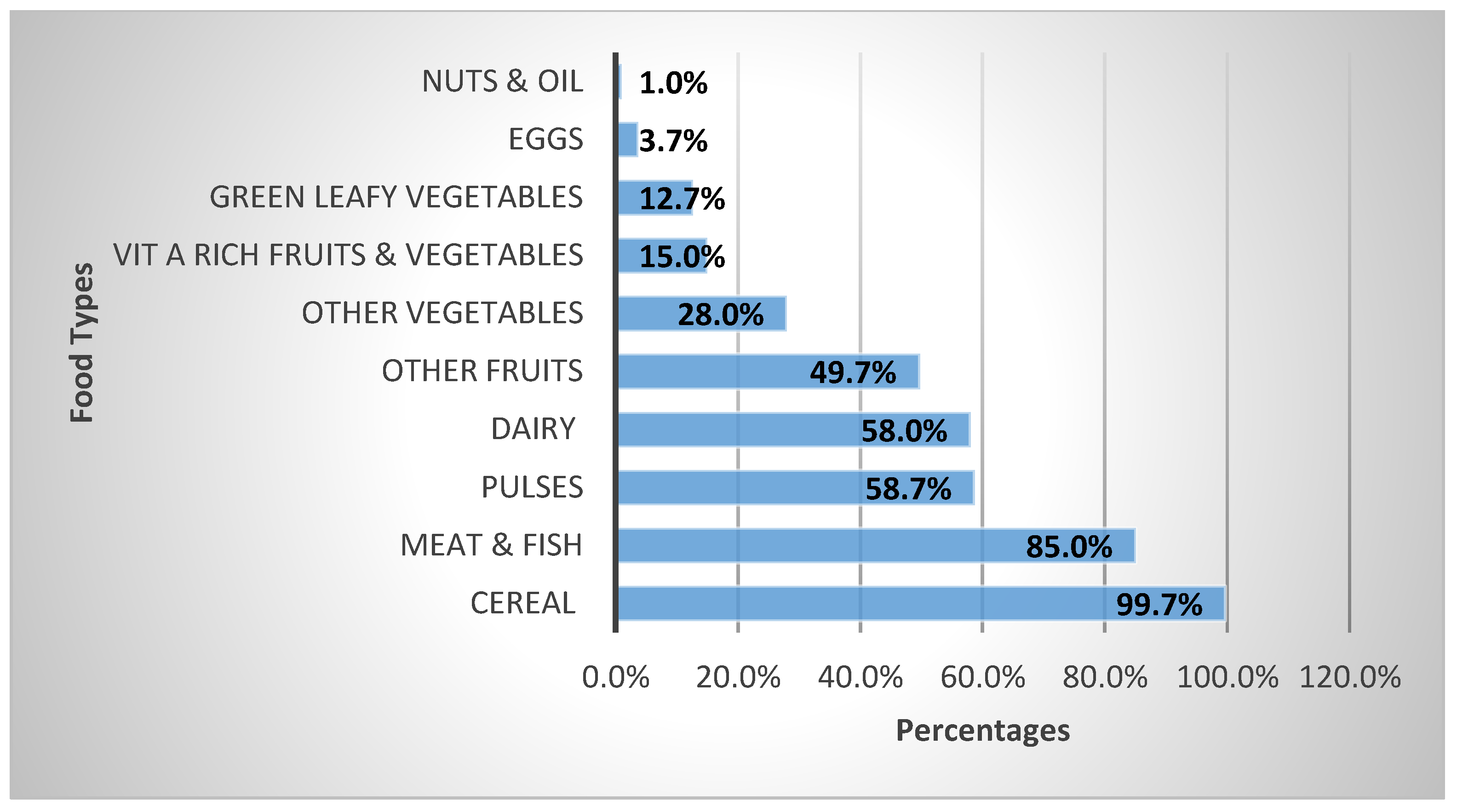

Figure 1 shows the consumption of different food groups by the participants at least one time per day over one week. Almost all women had consumed grains, roots and tubers. Eighty-five per cent of the women had meat, poultry and fish. On the other hand, a large majority of the women did not consume nuts and seeds (99%), eggs (96%), vitamin A-rich fruit and vegetables (85%), GLV (87%), other vegetables (72%) and other fruits (50%). Over 40% of the women did not consume dairy and pulses. The mean (SD) DDS was 4.12 (

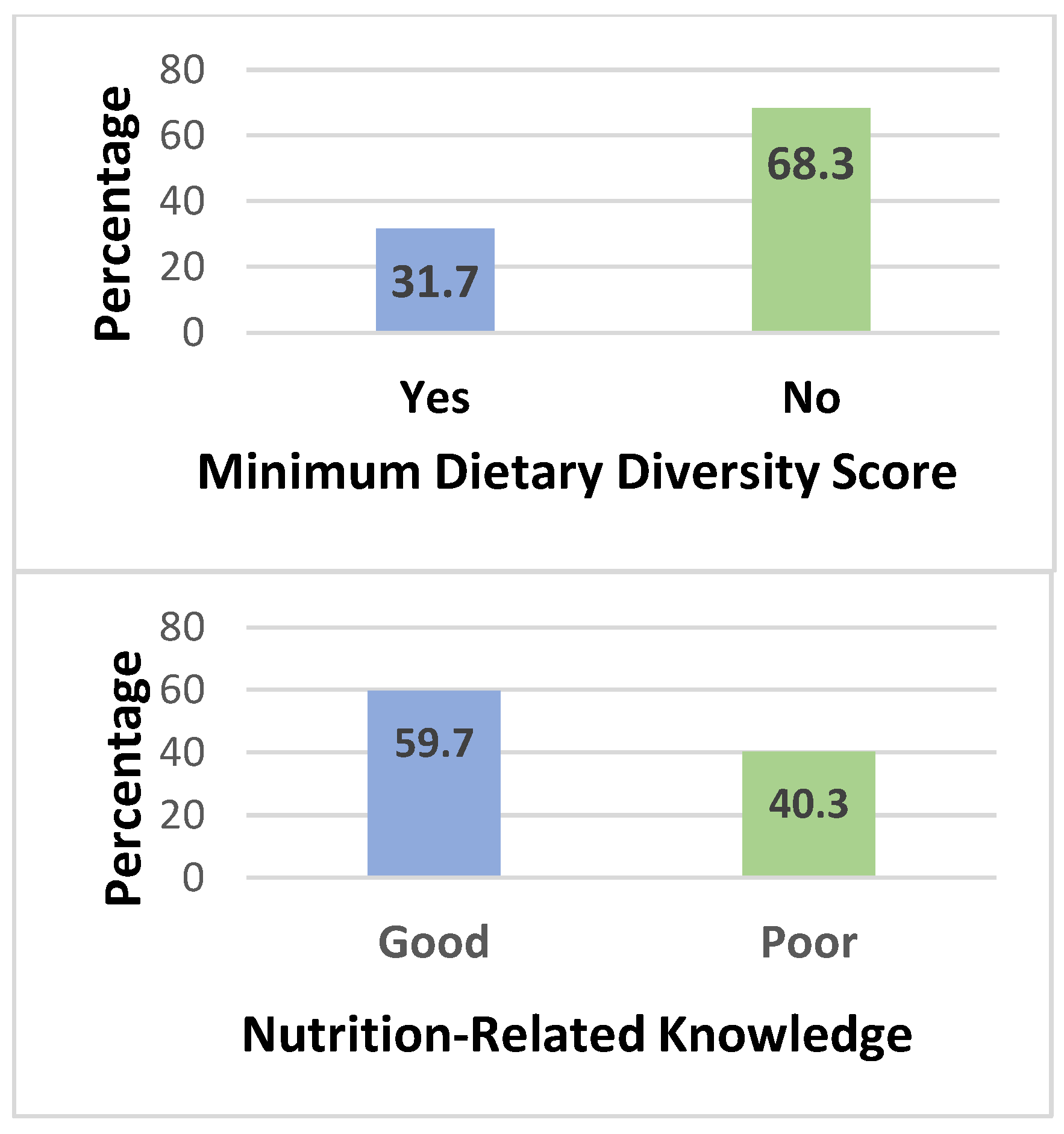

+1.49), with a median (range) of 4.0 (1-9). Nearly 65% of the working women did not meet the minimum DDS (Figure 2).

Table 3 depicts the proportion of working women who correctly answered nutrition-related knowledge questions. Over 80% of the working women answered correctly about a balanced diet. More than 95% of the women knew about the good sources of protein (98.7%), carbohydrates (96%) and fat (98%). Over 80% of the women knew about the foods that are rich in iron, the foods that can increase and/or decrease iron absorption, and about health consequences of low intake of iron-rich foods. Over half (53.3%) of the women articulated that the importance of fruits and vegetables is only due to their vitamin and mineral contents. Around 70% of the women stated that vitamins as a good source of energy and 60% reported skipping a meal is a good way to lose weight which were incorrect. Nearly half (45%) of the women did not know that oily fish contains healthier fat than red meat fat. A similar proportion (44.3%) also did not know that obesity is associated with chronic diseases such as heart disease.

The mean (SD) nutrition-related knowledge score was 11.95 (+2.04), with a median (range) of 12.0 (2-16). As shown in Figure 2, about sixty (59.7%) of the women had good knowledge (knowledge score >12), while the rest (40.3%) had poor knowledge (knowledge score <12).

The study participants were asked about their feelings towards their current weight status, healthy eating, and behaviours (

Table 4). Over a quarter (28.3%) of the women stated that their current body weight is harmful to their health and nearly 40% of women said they were motivated to lose weight. Twenty-one per cent of the women said they are not satisfied with their current level of physical activities, while another 28% said they are satisfied. A quarter of the study participants said small and frequent meals help in weight reduction. A large majority (88%) said eating breakfast is part of a healthy lifestyle, while 36% of the women said eating a mixed diet regularly is a healthy eating behaviour.

The mean (SD) nutrition-related attitude score was 21.8 (

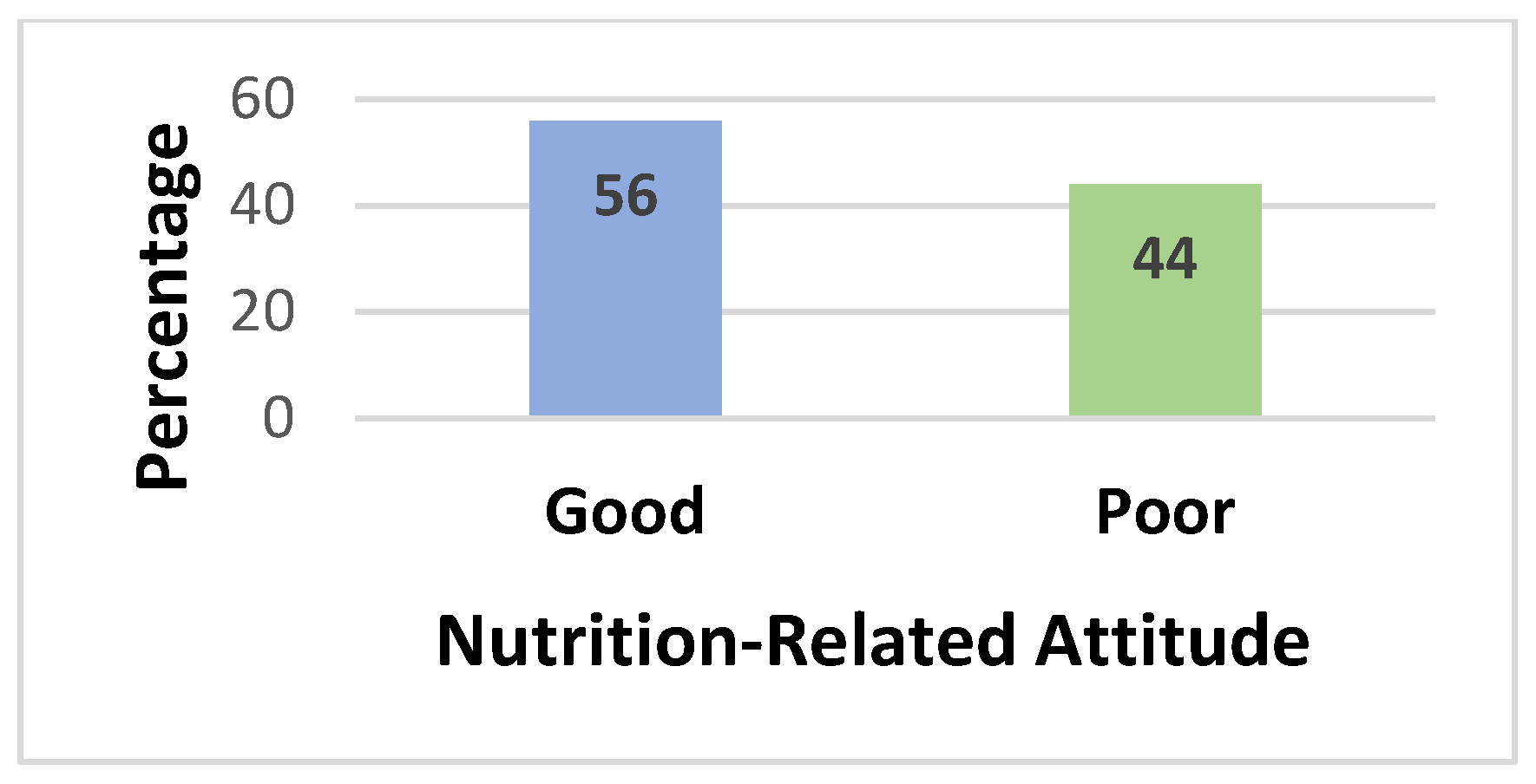

+3.50), with a median (range) of 22.0 (13-29). Overall, 56.0% of the participants had good attitudes (attitude score

>22) and the rest of the 44.0% had poor attitudes (attitude score <22;

Figure 2).

The association of DDS with nutrition-related knowledge, attitudes and various sociodemographic variables were tested using Pearson’s correlation. There were significant positive associations between the DDS and age of the participants (r=0.157;

p=0.006), education level of the participants (r=0.214;

p=0.000), spouse’s education level (r=0.202;

p=0.000), household income (r=0.273;

p=0.000) and nutrition-related knowledge (r=0.159;

p=0.006). On the other hand, the dietary diversity score was negatively associated with the duration of work/week (r=-0.209;

p=0.000). Factors influencing the DDS of the working women were evaluated using a backward stepwise multiple regression analysis (

Table 5).

When age, level of education, duration of work (hours/week), spouse’s education level, household income, nutrition-related knowledge and attitudes were included in the analysis and using a p=0.10 for exclusion level of education, duration of work (hours/week), spouse’s education level dropped out of the model. Among the variables left in the equation, age and household income were significantly independently related to DDS, while nutrition-related attitudes were negatively associated. There was a positive independent association between DDS and nutrition-related knowledge, however, it did not reach statistical significance (p=0.057). The household income bore a stronger association with DDS compared to other variables judged by the comparable beta coefficient. The overall F ratio was 8.46 (df=4) and was highly significant (p=0.000). The adjusted R square was 0.093 (multiple R=0.325) suggesting the variables in the equation accounted for a 9.3% variance in dietary diversity score.

4. Discussion

This study provides insight into the nutritional status, dietary pattern and nutrition-related knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating among working women in Western Province, Sri Lanka. To our knowledge, this is the first study that focused on working women in Sri Lanka. Overall, the majority of the participants came from educated families and relatively higher social positions and better economic conditions.

Over half of the working women were either overweight (38%) or obese (13%), whereas only a few (2.7%) were underweight. While there are no data on working women, Sri Lankan Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) 2016 reported a 32% of prevalence of overweight and a 13% prevalence of obesity among ever-married women aged 15-49 years [

23], which is very similar to our study findings.

The data on usual dietary patterns, based on 7-day FFQ, revealed a wide variation in intake patterns. First, comparing the frequency of intake of the foods of animal origin each week, fresh fish was most frequently consumed, followed by dry fish, chicken, and eggs. Looking at the distribution of the frequency of consumption, nearly 70% of the working women had fresh fish and 43% had dry fish at least 4 times a week. Both fresh fish and dry fish are good sources of protein in the Sri Lankan diet. Additionally, fish, particularly oily fish contain omega-3 fatty acids and regular consumption of fish may help reduce the risk of heart disease, and stroke [

24]. Over two-thirds of the working women had eggs only occasionally (1-3 times a week) or no eggs at all. Eggs are a very good source of protein and some vitamins, such as vitamins A, D, and B

12. Quite surprisingly, red meat such as mutton, pork, beef, and organ meat was not so popular- over 80% of the working women did not consume these foods at all in the week preceding the interview. While there is a lack of data on detailed food consumption patterns of Sri Lankan women, a study conducted among rural adults in dry-zone Sri Lanka also reported a very similar eating pattern with 54% having fish, 12.5% having eggs and only 7.5% had meat and meat products, and there was no significant difference in mean consumption pattern between males and females [

25]. However, this study assessed the food consumption pattern used 24-h dietary recall method. Of note, low intake of red meat, and organ meat are healthy eating habits, as regular consumption of larger quantities of red meat may be associated with an increased risk of colorectal cancer [

26] and associated with increased consumption of saturated fat, unless lean meat, a known risk factor for cardiovascular disease [

27].

The food consumption data also revealed that the intake of pulses is reasonably high with 85% of the women consumed at least 4 times a week. While not directly comparable, the Sri Lankan DHS 2016 reported, based on 24-h dietary recall, that over two-thirds of the women of reproductive age had legumes/pulses on the day preceding the interview [

23]. Pulses are a good source of plant protein, and fibre, as well as a significant source of vitamins and minerals, such as iron, zinc, folate, and magnesium, and regular consumption of pulses is associated with reduced risk of several chronic diseases [

28].

In the present study, we found that one in four working women did not consume milk and milk products at all and another 20% of the women had it occasionally. The Sri Lankan DHS 2016 also showed that only 20% of the women had milk and yoghurt on the day preceding the interview [

23]. Dairy products contain vitamin D and other minerals for instance calcium, phosphorus which is important for the maintenance of bone health and reducing fractures [

29,

30].

The intake of other vegetables and fruit intakes was reasonably high among the study participants with median consumption of 10 times/week. Further, our data showed more than 80% of women had other vegetables and fruits at least 4 times per week. However, one-third of the women had GLV only occasionally, i.e., 1-3 times a week or not at all. These foods are nutrient-dense, relatively low in energy and are good sources of minerals and vitamins, dietary fibre and a range of phytochemicals including carotenoids [

31]. The health benefits of consuming diets high in vegetables and fruit have been reported for decades [

32,

33].

Almost all the participants (99%) regularly consumed grains/cereals with a mean consumption of 20 times/week, which is expected as rice is the staple food in Sri Lanka. Further, tubers (mostly starchy vegetables) intake was also relatively high with a mean consumption of 4.5 times a week. Typical Sri Lankan cuisine contains mainly a larger portion of boiled or steamed rice with a curry of fish or meat or egg along with other curries made with lentils (pulses), starchy vegetables such as potato, breadfruit, jackfruit, manioc- predominantly carbohydrate diet. The Sri Lankan DHS 2016 also reported that 96% of the women had grains and 55% had roots and tubers on the day preceding the interview [

23].

In the present study, we observed a mean DDS of 4.12 based on the consumption of different food groups at least one time, irrespective of portion size, per day over one week. Looking at the findings of DDS, a large majority of the women did not consume eggs (96%), vitamin A-rich fruit and vegetables (85%), or GLV (87%) at least one time a day in the week preceding the survey. Additionally, nearly half of the women did not consume other fruits, dairy and pulses. Similar to the findings of our study, Abeywickrama et al. in their study reported that only 10% of the rural adults in dry-zone Sri Lanka had any fruit, and around 40% had GLV [

25]. The Sri Lankan DHS 2016 also reported that 88% of the women of reproductive age did not consume vitamin A rich fruits and vegetables, 50% had no other fruits, and 69% had no legumes/pulses on the day preceding the interview [

23]. However, Abeywickrama et al. and the DHS 2016 reported the consumption of various food groups based on 24-h dietary recall method [

23,

25]. Moreover, the food groups used were also not comparable with our study, except few. We also estimated the proportion of women meeting the minimum DDS according to FAO guidelines [

19], which indicates micronutrient adequacy in the diet [

34]. Nearly two-thirds of the women did not meet the minimum DDS indicating that they are unlikely to meet their daily micronutrient needs.

Processed meat, fast food and snacks are classified as discretionary choices because they are energy dense and high in saturated fat, trans fat and/or salt. Regular consumption of these foods is known to be associated with an increased risk of becoming overweight or obese, which can lead to the development of several chronic diseases [

35]. In the present study, we found that about half of the women had processed meat (49%) or fast food (50%) 1-3 times a week preceding the interview, while the consumption of snacks was very high with a mean intake of 4.8 times/week. A study conducted among working mothers of preschool children in Mumbai, India also reported high consumption of fast food [

10]. Like the findings of the present study, a study conducted among working women in Jabalpur, India has also reported the habit of taking snacks in a regular pattern [

11]. Another study from Odisha, India also reported that two-thirds of the working women had snacks once a day [

36]. Our data also showed that nearly two-thirds of the working women consumed tea and coffee with sugar seven times or more per week. Nearly half of the working women had fruit juice and 27% of the women had sugar-sweetened beverages 1-3 times a week. Consumption of added sugars has been associated with an increased risk of obesity [

37] as well as increased risk factors for developing diabetes [

38].

According to the Knowledge, Attitude and Practice theory, the process of human behaviour change occurs in three steps: acquiring knowledge, generating attitudes/beliefs, and forming practice/behaviours [

39]. The present study revealed that more than half of the working women had good basic nutrition-related knowledge and favourable attitudes to weight status and healthy eating. A study conducted among reproductive-age women in marginalized areas in Sri Lanka showed that the average knowledge score of employed women was higher than unemployed women [

15].

In the present study, we also identified factors associated with DDS in working women. Our findings revealed that age and household monthly income were significantly independently associated with DDS. Household income, an indicator of socio-economic status, has been consistently found to be associated with the consumption of a better-quality diet. For example, a study among US adults suggested that a better socioeconomic status index is independently associated with adequate fruit and vegetable intake and overall diet quality [

40]. Another study from Iran also showed that families with good socio-economic status significantly consumed more fruit, vegetable, dairy group, red meat, chicken and poultry, fish and egg [

14]. The positive association between age and DDS could be due to the relatively better nutrition knowledge among older women, and their ability to make better food choices. Of note, we observed a positive correlation between age and nutrition-related knowledge (data not shown). Similarly, previous studies have shown that older women have better nutrition knowledge [

41]. Earlier studies have shown that nutrition-related knowledge is associated with a healthy eating pattern [

14,

41,

42]. In the present study, we found a trend of a positive association between nutrition-related knowledge and DDS, with a marginally significant (

p=0.057). While we observed a possible association between knowledge and attitudes (data not shown), nutrition-related attitudes were negatively associated with DDS. The reason for this unexpected finding could be due to the content of attitudes questions not well-captured the dietary diversity rather focused on weight status. Further, studies are warranted to confirm the association between attitudes and DDS

The present study has some limitations. First, this study was conducted on a convenience sample; thus, the study findings may not be representative of the wider population, so the results should be interpreted with caution. Second, the sample size was relatively small considering the nature of the data, which may have introduced some bias. Third, the lack of data on portion size limits information regarding the actual consumption of energy and nutrient intake. Forth, data obtained using a cross-sectional survey did not allow us to determine the causality.

One of the strengths of our study is that the DDS calculation was based on the average daily consumption of any food groups over a reference period of the previous 7 days. Thus, this method is likely to give more accurate and reliable estimates of the diversity of diet than a DDS calculated using a single 24-hour recall. The present study used multivariate analysis to identify the potential determinants of DDS, by controlling the effect of confounders, in this population group. In addition, this study, for the first time, provided a snapshot of the dietary pattern, nutrition-related knowledge and attitudes of working women in Sri Lanka and their association, which can help design further research to improve the overall situation of this population group.