1. Introduction

Surgery by primary laryngectomy has long been the only therapeutic option for laryngeal cancer; however, in the second half of the 20th century surgical and non-surgical options for effectively curing laryngeal cancer avoiding total laryngectomy have been progressively validated [

1]. In the nineties, non-surgical organ preservation protocols (primary radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy (CRT) were validated as curative options for treatment of a subgroup of patients with locoregionally moderately advanced laryngeal cancers (stage II to IVa, with the exclusion of cT4a). Such protocols have been reported to obtain survival rates non inferior to surgery while allowing laryngeal preservation, with a reported success rate up to 75%, thus improving patient’s quality of life by preserving larynx-related functions, such as breathing, swallowing and speech. Such non-surgical laryngeal preservation protocols are now considered the standard method of treatment in many guidelines [

2]. However, despite the effectiveness of radio(chemo)therapy in managing these cases, many patients (up to 50%) still need a total laryngectomy afterwards [

3]. The indications for surgery include persistent or recurrent tumors (salvage laryngectomy), the development of chondronecrosis, or a dysfunctional larynx [

2,

4].

Radiotherapy and chemotherapy harm the normal tissues around the tumor in the clinical target volume (CTV), causing a considerable inflammatory response, dose-dependent vascular damage, altered perfusion, ischemia, extensive scarring, and fibrotic tissue remodeling, impairing the supply of nutrients and oxygen necessary for tissue regeneration and affecting tissues’ ability to heal [

2,

5]. As a consequence, complications rate will increase up to 64% in case of a total laryngectomy after irradiation [

4]. The most important and common complication caused by defective tissue healing is pharyngocutaneous fistula (PCF) with a reported incidence between 30 and 75% [

2,

6,

7].

Bulky tumors, supraglottic tumors, hypopharyngeal tumor extension, positive surgical margin, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, low postoperative hemoglobin level <12.5 g/dL, hypoalbuminemia, concurrent neck dissection, prior tracheotomy, lengthy operation, and type of closure of neopharynx are all factors affecting PCF development after post-radiotherapy salvage laryngectomy [

8,

9].

As a result of PCF, hospital stay is prolonged with a resultant increase in costs and delay in the start of both adjuvant therapy (when recommended and if possible), and oral feeding: in fact, the persistence of the fistula and/or the resultant stricture may lead to a long-term feeding tube dependence [

2].

Furthermore, PCF also leads to an increase in mortality rate, mostly through bleeding from vascular blowouts due to the erosion of major neck arteries [

9]. For these reasons, large and/or persistent PCF may require revision surgeries.

The high rate of PCF and its complications led many authors to recommend surgical measures to reduce the incidence of fistulae following total laryngectomies after irradiation [

2]. These surgical measures mostly involve the transfer of well vascularized and non-irradiated tissues, such as those coming from free microvascular flaps and pedicled regional flaps (pectoralis major is the most commonly used) [

1]. By doing this, the hypoxic fibrotic tissues receive better local oxygen and nutrient delivery, enhancing their capacity to heal [

5]. Pectoralis major flap is the most commonly used method of reconstruction as it is bulky, easy to be harvested, requires less time when compared to free flaps, and is used as a patch for defective mucosal parts in the neopharynx or is onlayed over sutured areas in the neopharynx, therefore reducing STL complications [

10,

11].

This study aims to review the outcomes in patients undergoing salvage total laryngectomy and reconstruction by pectoralis major flap (PMMF) (onlay myofascial flap or myocutaneous flap) either immediately (as prophylaxis) or after the development of pharyngocutaneous fistulae.

2. Materials and Methods

Interventionary studies involving animals or humans, and other studies that require ethical approval, must list the authority that provided approval and the corresponding ethical approval code. This is a retrospective observational study held at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) in Egypt including all cases of total laryngectomy with or without partial pharyngectomy, performed after radio(chemo)therapy with a radical intent and reconstructed by pectoralis major flap (either myofascial or myocutaneous), immediately or after the onset of fistula, in the period going from January 2015 to December 2021. We reviewed paper- and computer-based records and data extracted from the hospital information system including the data displayed in

Table 1 for each patient.

Cases of primary total or subtotal laryngectomy, patients who did not complete radio(chemo)therapy, patients still alive with a follow up shorter than 6 months and patients submitted to laryngectomy for tumors not originating from the larynx were excluded.

The minimal staging work up of laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma in the National Cancer Institute of Egypt includes a High Definition (HD) videolaryngoscopy, a microlaryngoscopy under general anesthesia, and a multislice-spiral contrast enhanced CT of the neck and of the lungs.

Surgical Technique and Post-Operative Management

Indication to total laryngectomy was given only for resectable lesions and in the absence of distant metastases in the post-irradiation work-up.

A standard total laryngectomy was carried out, along with or without a thyroidectomy, neck dissection, or partial pharyngectomy, depending on the tumor spread. If the tumor had invaded the skin, it was removed en bloc with the larynx. In cases with sufficient surface of pharyngeal mucosa after the laryngectomy (i.e., without a major pharyngectomy defect) a primary closure of the pharynx was performed with a T-shaped, two-layer vicryl 3-0 suture.

In some of these cases such reconstruction can be deemed sufficient, in the present series these cases have been included because of a following fistula treated with myocutaneous pectoralis major flap.

In most cases of primary closure of the pharynx, a myofascial flap of the pectoralis major was lifted and tunneled into the neck, and the muscle and its fascia were stitched to the base of the tongue, prevertebral fascia, and constrictor muscles as an onlay graft. The myocutaneous pectoralis major flap was recommended in case of: large pharyngeal defects not allowing T Shaped primary pharyngeal closure: in these cases the skin portion was employed to replace the missing mucosal surface as an interposition flap and cervical skin defects: in these cases the cutaneous paddle of the flap was used to restore the skin in the cervical defect.

An elective selective (levels II to IV) neck dissection was performed in high risk cN0 patients at the original and preoperative work up while a comprehensive (level I to VI) neck dissection was performed in cN+ cases at the original and/or preoperative work up; the neck was managed by observation in low risk cN0 cases at the original and preoperative work up.

Size 12 Fr vacuum drainage tubes were positioned two centimeters away from the pharyngeal suture line, along each side of the neopharynx. Feeding by nasogastric (NG) tube started on the first postoperative day. By the eighth postoperative day, if there was no sign of fistula or pus in the tube drains, a liquid and soft diet was introduced, and on the following day, the NG tube was withdrawn, after the removal of neck drains.

Tracheoesophageal puncture was never performed at the time of laryngectomy, but delayed upon complete recovery from surgery.

Statistical analysis

The primary endpoints included overall survival and disease-specific survival calculated from the time of salvage (OS and DSS) surgery. Survival curves were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. For comparing survival curves, we used the Wilcoxon test. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed by Cox’s proportional hazards model. The α level was set at 0.05 for all statistical tests. Statistical analysis was computed using the JMP in software, release 7.0.1, from the SAS institute.

3. Results

Detailed descriptive statistics are displayed in

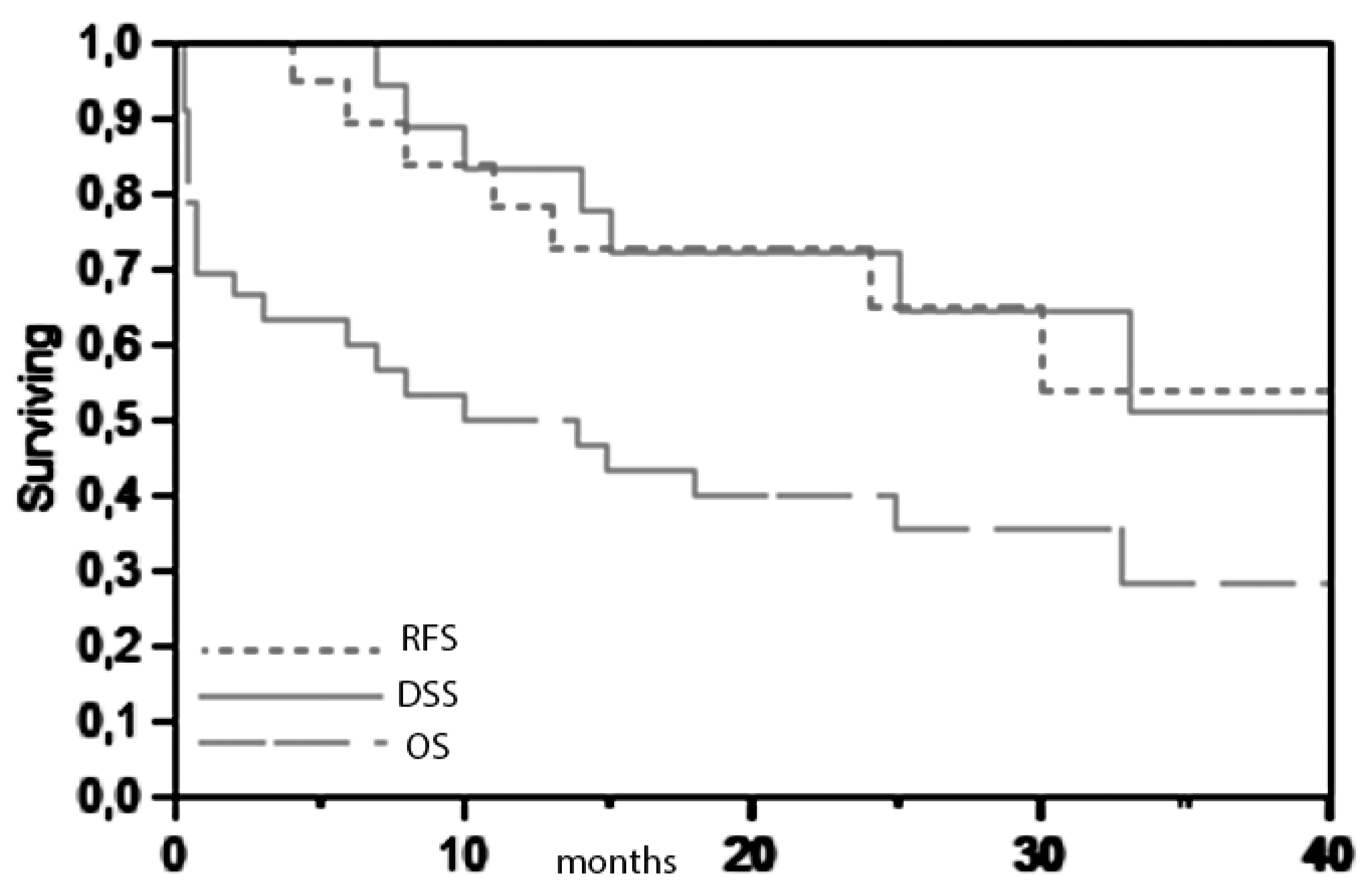

Table 1. The 3-year overall and disease specific survival in the present series are respectively 28% and 51% (

Figure 1).

In the present series, all the patients with recurrences died from the disease, therefore, by checking the impact on DSS of the different parameters, we also evaluated the impact on relapse free-survival. Only 7 recurrences (2 distant and 5 locoregional) and 7 consequent deaths for cancer were recorded. The other 14 deaths derived from other causes, mostly (9/14) related to the treatments (irradiation and salvage surgery).

The relatively small dimensions of the sample and the high number of deaths for causes differing from cancer prevented our ability to obtain statistical significance for any of the parameters evaluated in relation to disease control (disease specific survival). Anyway, notably and not surprisingly, all cases with R1 laryngectomy samples died within 15 months after the surgery (both for cancer and other causes).

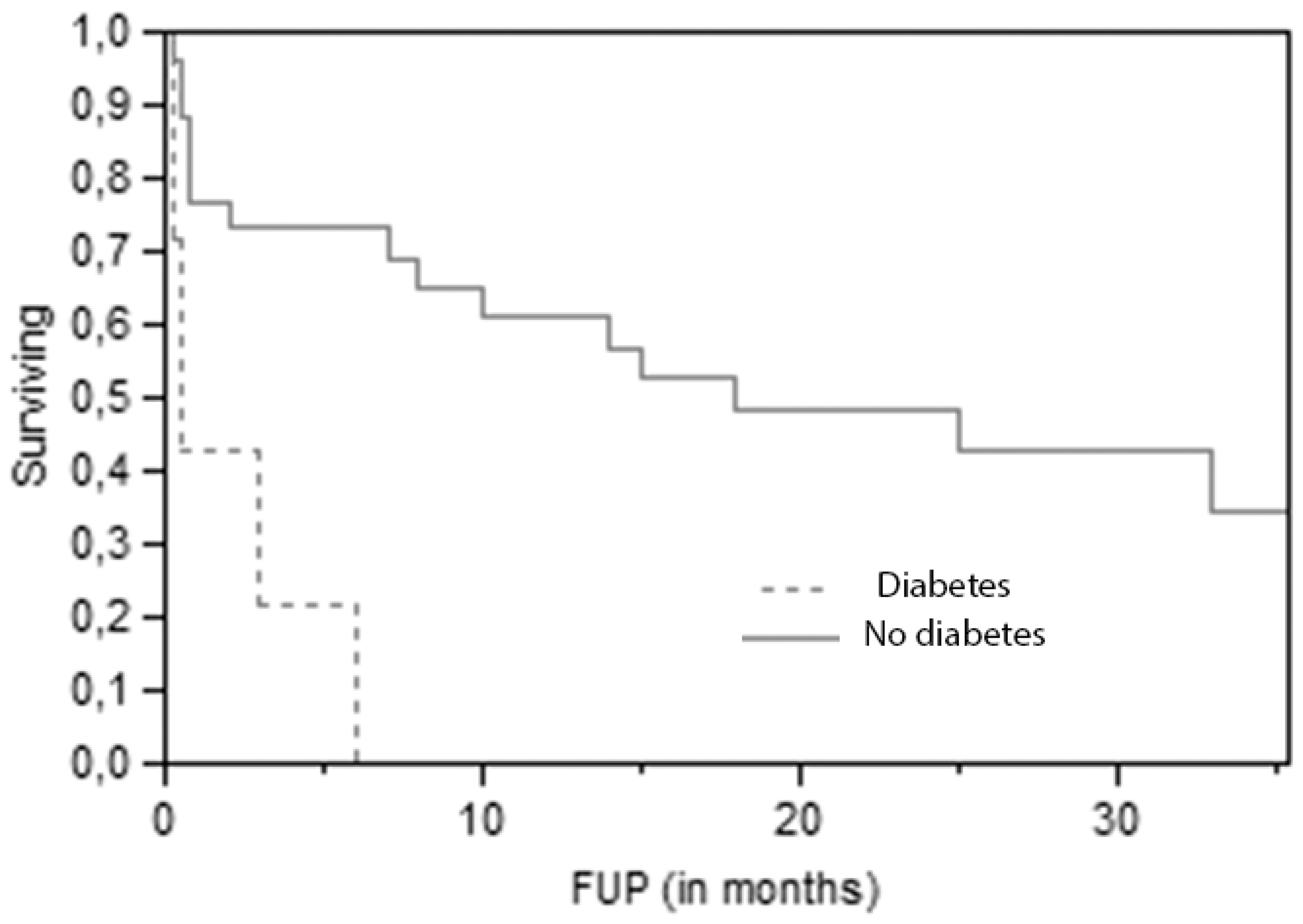

The most significant (p=0,0009 at Log-Rank test) predictive parameter for overall survival is diabetes (

Figure 2).

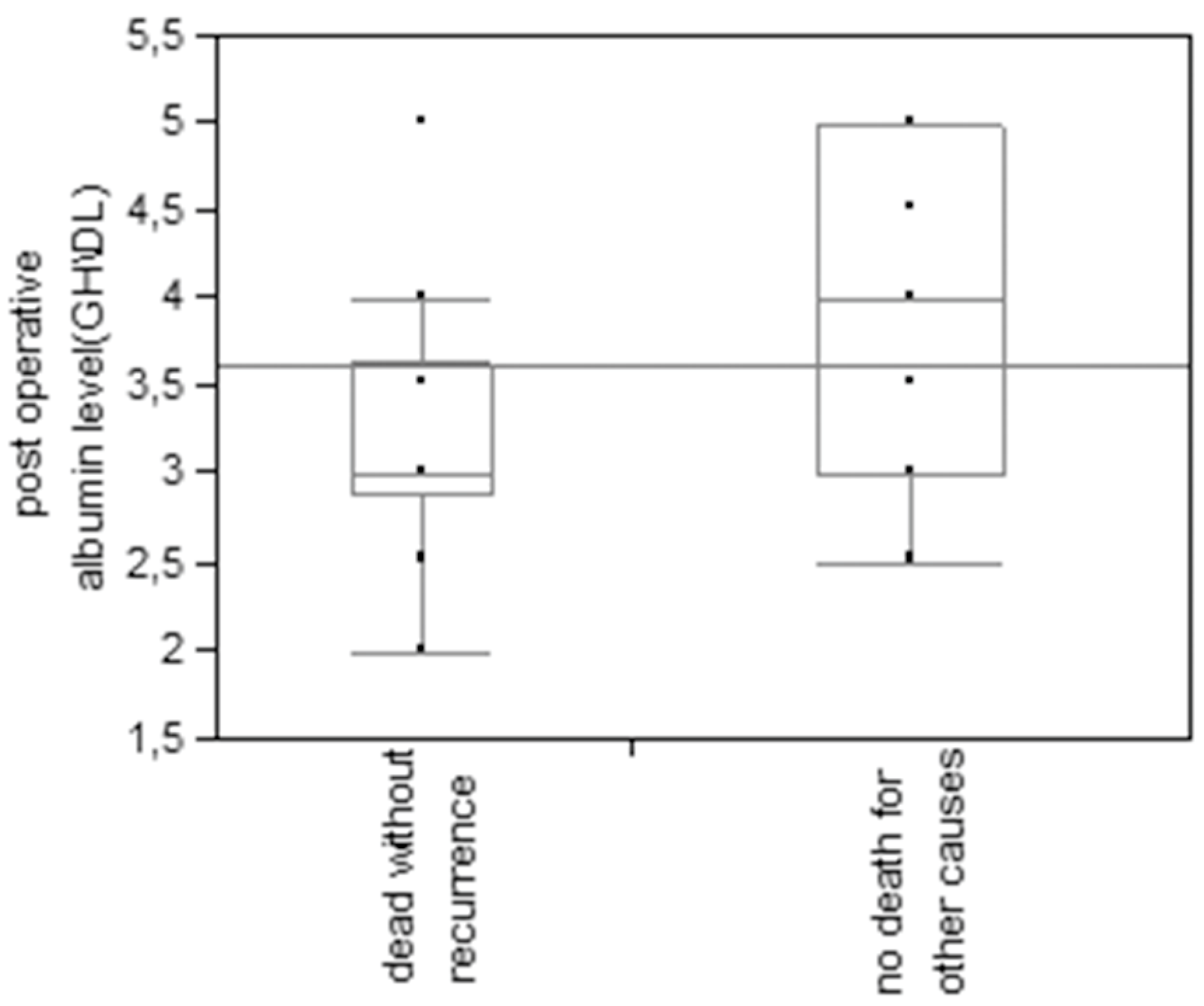

This finding is even more striking when only non-cancer-related deaths are considered, as only 30,8% of patients without diabetes died for other causes, against 69,2% of diabetic patients (p=0.009 at Pearson test). Also lower postoperative albumin levels (on the fifth day after surgery) were associated with a higher risk of death for other causes (p=0.008 at t test) (

Figure 3).

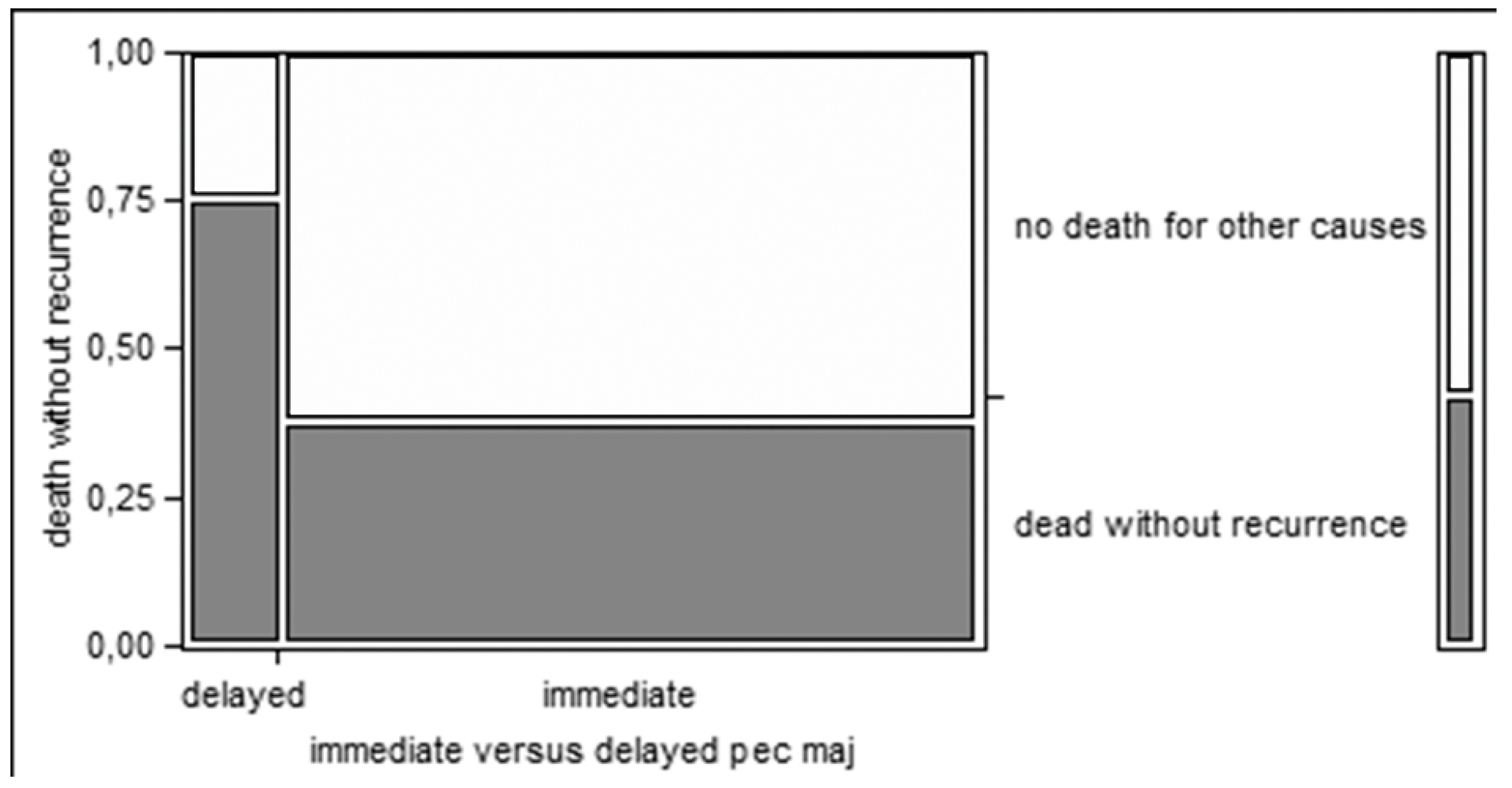

Moreover, delayed reconstruction after the onset of fistula, rather than immediate reconstruction, seems associated with a higher risk of non cancer-related deaths (75% vs. 38%), even if without statistical significance (

Figure 4).

40.5% of patients had a voice prosthesis. All the voice prostheses were placed secondarily after a careful selection and were successfully used by patients for voice rehabilitation.

4. Discussion

Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted. The 5-year OS of laryngeal cancer in United States went from 67% in 1977 to 64% in 2004, and it remains, together with the adenocarcinoma of the uterine body, the only major human cancer without a significant improvement of survival in the past 30 years in many Western countries, despite the evident technical, technological and methodological advances of head and neck oncology. These data are even more striking if compared with the ones reported for oral SCC, the other most frequent head and neck malignancy, which passed from a 53% to a 60% 5-year survival in the same period [

12,

13,

14].

Many explanations have been suggested to justify such trend [

15]. Among them many authors cite the increasing push toward surgical and non surgical function preserving treatments [

16]. In fact nowadays, more than ever before, in clinical oncology a premium is placed on returning the patient to a productive and useful lifestyle (i.e., quality of life after cancer treatment); this attitude is demonstrated more keenly in the treatment of larynx cancer than with almost any other malignancy; and swallowing, phonation, breathing and esthetic appearance of a patient treated for laryngeal cancer have become pretty relevant endpoints. This led to the emergence of conservative strategies, both surgical, with the codification of partial operations, and non-surgical, with a variety of combinations and sequences of chemotherapy and radiotherapy; the common aim is organ and/or function preservation [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24].

As for non-surgical strategies, they have been tested for cT3 and selected cT4 LSCCs with oncological results reportedly comparable with total laryngectomy. In particular the Veteran Affairs study group showed that a treatment strategy involving induction chemotherapy and definitive radiation therapy in responders can be effective in preserving the larynx in a high percentage of patients (64% at 2 years), without compromising overall survival (the estimated 2-year survival was 68 percent for both treatment groups), if compared with total laryngectomy, followed by adjuvant radiotherapy in the non-responders group [

24]. A more recent study [

17] demonstrated that primary treatment with radiotherapy and concurrent cisplatin (100 mg per square meter on days 1, 22, and 43), while obtaining the same results as for overall survival (75% at 2 years, 55% at 5), was associated with a significantly higher relapse free survival (78% vs 61%) and consequently higher larynx preservation rate (88% vs 75%) than induction chemotherapy plus definitive radiotherapy. At present the concurrent radiotherapy plus cisplatin as described by Forastiere remains therefore the standard non-surgical organ preservation protocol [

25] which has been employed also in the vast majority of the patients in the present study as primary treatment.

Some studies, contradicting the results by the Veteran Affair Study Group and Forastiere, reported a survival advantage for patients treated primarily with surgery [

26], leading to hypothesize that the reason for the failure in improving prognosis of laryngeal cancer is the diffusion of chemoradiotherapy as primary treatment in stage II, III and IV [

27]. Actually definite scientific statistical proofs supporting such thesis are lacking, and the thesis itself does not consider the wide diffusion, not supported by robust statistical evidence, of organ preserving operations as well.

In fact, if non-surgical preservation strategies by radiochemotherapy are supported by large amount of data and are included in the most important international guidelines [

25] for stage III and selected stage IV LSCC, surgical preservation strategies had not been validated by large prospective studies, neither extensively compared with radiochemotherapy, but are included among the treatment options for LSCC [

16,

28] basing upon several clinical series. These studies reported a 5-year overall survival rate over 80% in stage III and IV LSCC, comparable with total laryngectomy [

18] [

19,

28,

29,

30]. Not every advanced LSCC is anyway susceptible of a supracricoid resection, the main contraindications according to most authors are: true arytenoid fixation, base of tongue involvement, massive preepiglottic space or vallecular invasion, cricoid cartilage involvement (10mm anterior / 5 mm posterior), interarytenoid involvement, extensive thyroid cartilage involvement, inability to adhere to post-operative care and rehabilitation [

23,

31].

Anyway primary total laryngectomy (with neck dissection and, when indicated, followed by RT+ CT) still remains the gold standard for disease specific survival, and the comparison term for every clinical trial evaluating the oncological outcome of organ/function preserving strategies in advanced LSCC also in the future.

The non-surgical laryngeal preservation protocols, and namely radiotherapy, induction chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy and concomitant radiochemotherapy, were reported to obtain a laryngeal preservation rate up to, respectively, 70%, 75% and 88 %, at two years [

17] in advanced laryngeal cancer. Anyway, the long term follow up of the same series shows that laryngectomy free-survival rate continues to decrease along the years more rapidly in the concomitant group (with an higher rate of laryngeal preservation but a higher mortality for non-cancer causes) with less than 30% of patients surviving after 10 years with their larynx in place in all three groups [

32].

Most importantly, the anatomic preservation of the larynx is not equivalent to its functional preservation at all, so most patients submitted to irradiation (especially if combined with chemotherapy) for moderately advanced laryngeal cancer complain about dysphagia [

33]. Also, differently from surgery, long term toxicities deriving from radio and chemoradiotherapy tend to worsen along years, with tissue remodeling, fibrosis, scar, edema, sensitivity issues, xerostomia, leading to recurrent aspiration pneumonia and weight loss and causing significant morbidity and mortality.

It also means that laryngectomies continue to be performed for a long time after non-surgical preservation protocols both for treating cancer recurrence and for functional issues after radiotherapy + chemotherapy.

The present work is an analysis of what happens in a real-world group of patients who need a total laryngectomy and a pectoralis major reconstruction after radiochemotherapy, both for oncological and for functional reasons. Pectoralis major reconstruction, in case of total laryngectomy, is performed to prevent or to solve an issue; therefore, the present series provides real-world information about an unfavorable group of total laryngectomies after irradiation.

We do believe that such data is precious because it is what happens in daily clinical practice, outside of the controlled environment of randomized clinical trials, where post-irradiation recurrences are often diagnosed late in patients with frequently severe comorbidities.In the present series, the number of patients (9/21 deaths) dying because of comorbidities and direct consequences of previous treatments (irradiation, chemotherapy, salvage surgery) is higher than the number of patients dying for cancer itself (7/21). In general, deaths without recurrences (14) are twice the deaths for cancer progression (n=7).

The high morbidity of laryngeal salvage surgery is deeply influenced by the general condition of the patients [

34]. In the present real world series, it turns out that the most relevant parameters predicting success and survival in major salvage surgery of the larynx are not cancer-related but patient-related parameters (diabetes, postoperative albumin levels).

Also the functions, and in particular swallowing, are often compromised in surviving patients, with only about 30% of patients reporting normal oral feeding (see

Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

| Age at diagnosis |

Mean

Range |

55.5

30-71 |

| Sex no. (%) |

Male

Female |

36(97.3%)

1(2.7%) |

| Cigarette smoking no.(%) |

Yes

No |

35(94.6%)

2(5.4%) |

| Diabetes no.(%) |

Yes

No |

7(18.9%)

30(81.1%) |

| T classification of primary tumor (before irradiation)- no. (%) |

1

2

3 |

2(5.4%)

22(59.5%)

13(35.1%) |

| N classification of primary tumor (before irradiation)- no. (%) |

0

1 |

35(94.6%)

2(5.4%) |

| Site of primary tumor no. (%) |

Glottic

Supraglottic |

27 (73%)

10 (27%) |

| Pathology of primary tumor no. (%) |

Squamous cell carcinoma

Adenocarcinoma |

36(97.3%)

1(2.7%) |

| Grading of primary tumor no. (%) |

I

II

III |

4(10.8%)

31(83.8%)

2(5.4%) |

| Duration between diagnosis and beginning of radiotherapy (months) |

Mean

Range |

3,2

1-15 |

| Primary organ preservation protocol, chemoradiotherapy no. (%) |

Radiotherapy alone

Concomitant chemoradiotherapy

Induction chemotherapy followed by concomitant chemoradiotherapy |

14(37.8%)

18(48.7%)

5(13.5%) |

| Duration between end of irradiation and recurrence (months) |

Mean

Range |

11,5

1-65 |

| T classification of recurrence, yT no. (%) |

2

3

4 |

2(5.4%)

19(51.4%)

16(43.2%) |

| N classification of recurrence, yN no.(%) |

0

1 |

34(91.9%)

3(8.1%) |

| Duration between diagnosis of recurrence and operation (months) |

Mean

Range |

2.6

1-7 |

| Partial pharyngectomy no.(%) |

Yes

No |

19(51.4%)

18(48.6%) |

| Cervical skin excision no. (%) |

Yes

3(8.1%)

No

34 (91.9%) |

| Pharyngeal closure of total laryngectomy defect no. (%) |

Interpositioned myocutaneous flap for mucosal defect

Myocutaneous flap, onlay insetting for pharynx, skin for external surfacing

Primary closure with onlay myofascial flap.

Primary closure |

18(48.7%)

3(8.1%)

12(32.4%)

4(10.8%) |

| Type of pectoralis major flap for total laryngectomy defect no.(%) |

Myocutaneous

Myofascial

Not done |

21(56.8%)

12(32.4%)

4(10.8%) |

| Thyroidectomy no. (%) |

Total

Hemithyroidectomy

Not done |

7(19%)

13(35.1%)

17(45.9%) |

| Neck dissection no. (%) |

Bilateral

Monolateral

Not done |

25(67.6%)

3 (8.1%)

9 (24.3%) |

| Surgical time(h) |

Mean

Range |

4.3

3-5 |

| Date of neck drain removal post-surgery(d) |

Mean

Range |

9

6-20 |

| T classification of total laryngectomy sample, pT no.(%) |

0 (Necrotic tissue)

3

4 |

1(2.7%)

11(29.7%)

25(67.6%) |

| N classification of neck dissection sample, pN (n=28) no. (%) |

0

1 |

20(71.4%)

8(28.6%) |

| Margins no.(%) |

R1

R0

Necrotic tissue |

8(21.6%)

28(75.7%)

1(2.7%) |

| Thyroid gland infiltration(n-20) no. (%) |

Infiltrated

Not infiltrated |

4(20%)

16(80%) |

| Duration of hospital stay postoperative(days) |

mean

range |

14

6-30 |

| Postoperative albumin level(gh\dl) |

mean

range |

3,6

2-5 |

| Pharyngocutaneous fistula no.(%) |

Yes

No

No data |

20(54.1%)

13(35.1%)

4(10.8%) |

| Postoperative day of appearance of fistula |

Mean

Range |

8.5

4-14 |

| Effects of fistula no. (%) |

Minor fistula

Wound dehiscence

Bleeding and death |

7(35%)

11(55%)

2(10%) |

| Date of repair of fistula since appearance(d) |

Mean

Range |

31.5

3-113 |

| Management of fistula no. (%) |

Conservative treatment

Trimming and primary closure

Trimming and repair by PMMF |

10(55.6%)

3(16.7%)

5(27.7%) |

| Results of management no.(%) |

Closed

Persistence and follow up

Necrosis of flap and repair by LD flap

Bleeding and death |

10(55.5%)

3(16.7%)

1(5.6%)

4(22.2%) |

| Postoperative bleeding no. (%) |

Yes

No

No data |

11(29.7%)

22(59.5%)

4(10.8%) |

| Site no. (%) |

Donor site

Neck |

3(27.3%)

8(72.7%) |

| Timing of bleeding (postoperative day) |

Mean

Range |

10.3

4-21 |

| Outcome of bleeding no. (%) |

Controlled by operation under GA

Death |

4(36.4%)

7(63.6%) |

| Recurrent malignancy no.(%) |

Yes

No

No data |

7(18.9%)

26(70.3%)

4(10.8%) |

| Type of recurrence no. (%) |

Local

Distant |

5(71.4%)

2(28.6%) |

| Management of recurrence no.(%) |

| Palliative chemotherapy |

7(100%) |

| Outcome of recurrent malignancy after surgical salvage no.(%) |

| Death |

7(100%) |

| Postoperative swallowing problems no. (%) |

Normal oral feeding

Tube feeding

Dysphagia requiring dilatation

Dysphagia not requiring dilatation

No data |

11(29.7%)

12(32.4%)

4(10.8%)

6(16.2%)

4(10.8%) |

| Postoperative speech rehabilitation by tracheoesophageal puncture and prosthesis no.(%) |

Inserted and functioning

Not inserted

No data |

15(40.5%)

18(48.7%)

4(10.8%) |

| Timing of TEP (months after surgery) |

Mean

Range |

6.9

6-12 |

| Outcome of follow up no.(%) |

Under follow up

Died

No data |

12(32.4%)

21(56.8%)

4(10.8%) |

| Cause of death no. (%) |

Carotid blowout

Venous blowout

Local recurrence

Distant metastases

Myocardial infarction

Septic shock

Intracranial hemorrhage

Sudden arrest

Obstruction of tracheostomy by secretions

Covid-19 |

6(28.6%)

1(4.8%)

5(23.8%)

2(9.4%)

2(9.4%)

1(4.8%)

1(4.8%)

1(4.8%)

1(4.8%)

1(4.8%) |

5. Conclusions

There is a certain debate in the literature about the indications to pectoralis major in salvage laryngectomy, with some authors [

7,

35,

36] advocating the routine use of pectoralis major in all laryngeal salvage surgeries after irradiation. The present data support such an attitude as a delayed reconstruction seems to be associated with a higher risk of non-cancer-related deaths also deriving from surgical complications.

In general, overall survival after post-irradiation laryngectomy and reconstruction with pectoralis major is low (28%) with most deaths (66%) not deriving from cancer progression or recurrence.

We can conclude that in these cases the main predictors are patients’ general conditions (in the present series diabetes and postoperative albumin levels).

These findings support the criticism about radio-chemotherapy as preferred primary treatment in T2/T3 laryngeal cancer, supported mostly by randomized clinical trials [

4] but already questioned by real-world data [

27] and by the epidemiologic data describing a decrease in survival of laryngeal cancer in recent decades in the US [

37,

38]. On the other hand, these results highlight the importance that pre- and post-operative medical management and nutritional care could have in improving the prognosis and the results of such demolitive surgeries, even more than the surgical technique itself.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Abdelghany, Amin, Hassan, Ftohy and Bussu; methodology, Abdelghany, Amin, Degni, Crescio, Hassan, Ftohy and Bussu; validation, Abdelghany, Amin, Degni, Crescio, Hassan, Ftohy and Bussu; formal analysis, Degni, Crescio and Bussu; investigation, Abdelghany, Amin, Degni, Crescio, Hassan, Ftohy and Bussu; data curation, Abdelghany, Degni, Crescio and Bussu; writing— original draft preparation, Abdelghany, Degni, and Bussu; writing—review and editing, Abdelghany, Amin, Hassan, Crescio, Ftohy and Bussu; supervision, Abdelghany and Bussu; project administration, Abdelghany and Bussu. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bussu F, Miccichè F, Rigante M, Dinapoli N, Parrilla C, Bonomo P, et al. Oncologic outcomes in advanced laryngeal squamous cell carcinomas treated with different modalities in a single institution: a retrospective analysis of 65 cases. Head Neck. 2012;34: 573–579. [CrossRef]

- Cabrera CI, Joseph Jones A, Philleo Parker N, Emily Lynn Blevins A, Weidenbecher MS. Pectoralis Major Onlay vs Interpositional Reconstruction Fistulation After Salvage Total Laryngectomy: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;164: 972–983. [CrossRef]

- Bussu F, Paludetti G, Almadori G, De Virgilio A, Galli J, Miccichè F, et al. Comparison of total laryngectomy with surgical (cricohyoidopexy) and nonsurgical organ-preservation modalities in advanced laryngeal squamous cell carcinomas: A multicenter retrospective analysis. Head Neck. 2013;35: 554–561. [CrossRef]

- Weber RS, Berkey BA, Forastiere A, Cooper J, Maor M, Goepfert H, et al. Outcome of salvage total laryngectomy following organ preservation therapy: the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group trial 91-11. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129: 44–49. [CrossRef]

- Anschütz L, Nisa L, Elicin O, Bojaxhiu B, Caversaccio M, Giger R. Pectoralis major myofascial interposition flap prevents postoperative pharyngocutaneous fistula in salvage total laryngectomy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273: 3943–3949. [CrossRef]

- Sassler AM, Esclamado RM, Wolf GT. Surgery after organ preservation therapy. Analysis of wound complications. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;121: 162–165. [CrossRef]

- Patel UA, Moore BA, Wax M, Rosenthal E, Sweeny L, Militsakh ON, et al. Impact of pharyngeal closure technique on fistula after salvage laryngectomy. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139: 1156–1162. [CrossRef]

- Ikiz AO, Uça M, Güneri EA, Erdağ TK, Sütay S. Pharyngocutaneous fistula and total laryngectomy: possible predisposing factors, with emphasis on pharyngeal myotomy. J Laryngol Otol. 2000;114: 768–771. [CrossRef]

- Paydarfar JA, Birkmeyer NJ. Complications in head and neck surgery: a meta-analysis of postlaryngectomy pharyngocutaneous fistula. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132: 67–72. [CrossRef]

- Silverman DA, Puram SV, Rocco JW, Old MO, Kang SY. Salvage laryngectomy following organ-preservation therapy - An evidence-based review. Oral Oncol. 2019;88: 137–144. [CrossRef]

- Bussu F, Gallus R, Navach V, Bruschini R, Tagliabue M, Almadori G, et al. Contemporary role of pectoralis major regional flaps in head and neck surgery. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2014;34: 327–341.

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59: 225–249.

- Cann CI, Fried MP, Rothman KJ. Epidemiology of squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1985;18: 367–388. [CrossRef]

- Barclay TH, Rao NN. The incidence and mortality rates for laryngeal cancer from total cancer registries. Laryngoscope. 1975;85: 254–258.

- Almadori G, Bussu F, Cadoni G, Galli J, Paludetti G, Maurizi M. Molecular markers in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma: towards an integrated clinicobiological approach. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41: 683–693. [CrossRef]

- American Society of Clinical Oncology, Pfister DG, Laurie SA, Weinstein GS, Mendenhall WM, Adelstein DJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline for the use of larynx-preservation strategies in the treatment of laryngeal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24: 3693–3704. [CrossRef]

- Forastiere AA, Goepfert H, Maor M, Pajak TF, Weber R, Morrison W, et al. Concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy for organ preservation in advanced laryngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349: 2091–2098. [CrossRef]

- de Vincentiis M, Minni A, Gallo A. Supracricoid laryngectomy with cricohyoidopexy (CHP) in the treatment of laryngeal cancer: a functional and oncologic experience. Laryngoscope. 1996;106: 1108–1114. [CrossRef]

- de Vincentiis M, Minni A, Gallo A, Di Nardo A. Supracricoid partial laryngectomies: oncologic and functional results. Head Neck. 1998;20: 504–509. [CrossRef]

- Adelstein DJ, Li Y, Adams GL, Wagner H Jr, Kish JA, Ensley JF, et al. An intergroup phase III comparison of standard radiation therapy and two schedules of concurrent chemoradiotherapy in patients with unresectable squamous cell head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21: 92–98. [CrossRef]

- Pfister DG, Strong E, Harrison L, Haines IE, Pfister DA, Sessions R, et al. Larynx preservation with combined chemotherapy and radiation therapy in advanced but resectable head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9: 850–859. [CrossRef]

- Karp DD, Vaughan CW, Carter R, Willett B, Heeren T, Calarese P, et al. Larynx preservation using induction chemotherapy plus radiation therapy as an alternative to laryngectomy in advanced head and neck cancer. A long-term follow-up report. Am J Clin Oncol. 1991;14: 273–279. [CrossRef]

- Laccourreye H, Laccourreye O, Weinstein G, Menard M, Brasnu D. Supracricoid laryngectomy with cricohyoidopexy: a partial laryngeal procedure for selected supraglottic and transglottic carcinomas. Laryngoscope. 1990;100: 735–741. [CrossRef]

- Department of Veterans Affairs Laryngeal Cancer Study Group, Wolf GT, Fisher SG, Hong WK, Hillman R, Spaulding M, et al. Induction chemotherapy plus radiation compared with surgery plus radiation in patients with advanced laryngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1991;324: 1685–1690. [CrossRef]

- Forastiere AA, Ang KK, Brizel D. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Head and neck cancer www nccn org.

- Richard JM, Sancho-Garnier H, Pessey JJ, Luboinski B, Lefebvre JL, Dehesdin D, et al. Randomized trial of induction chemotherapy in larynx carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 1998;34: 224–228. [CrossRef]

- Hoffman HT, Porter K, Karnell LH, Cooper JS, Weber RS, Langer CJ, et al. Laryngeal cancer in the United States: changes in demographics, patterns of care, and survival. Laryngoscope. 2006;116: 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Laudadio P, Presutti L, Dall’olio D, Cunsolo E, Consalici R, Amorosa L, et al. Supracricoid laryngectomies: long-term oncological and functional results. Acta Otolaryngol. 2006;126: 640–649. [CrossRef]

- Nakayama M, Okamoto M, Miyamoto S, Takeda M, Yokobori S, Masaki T, et al. Supracricoid laryngectomy with cricohyoidoepiglotto-pexy or cricohyoido-pexy: experience on 32 patients. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2008;35: 77–82. [CrossRef]

- Rizzo D, Crescio C, Tramaloni P, De Luca LM, Turra N, Manca A, et al. Reliability of a Multidisciplinary Multiparametric Approach in the Surgical Planning of Laryngeal Squamous Cell Carcinomas: A Retrospective Observational Study. J Pers Med. 2022;12. [CrossRef]

- Holsinger FC, Weinstein GS, Laccourreye O. Supracricoid partial laryngectomy: an organ-preservation surgery for laryngeal malignancy. Curr Probl Cancer. 2005;29: 190–200. [CrossRef]

- Forastiere AA, Zhang Q, Weber RS, Maor MH, Goepfert H, Pajak TF, et al. Long-term results of RTOG 91-11: a comparison of three nonsurgical treatment strategies to preserve the larynx in patients with locally advanced larynx cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31: 845–852. [CrossRef]

- Hutcheson KA, Lewin JS, Barringer DA, Lisec A, Gunn GB, Moore MWS, et al. Late dysphagia after radiotherapy-based treatment of head and neck cancer. Cancer. 2012;118: 5793–5799. [CrossRef]

- Mattioli F, Bettini M, Molteni G, Piccinini A, Valoriani F, Gabriele S, et al. Analysis of risk factors for pharyngocutaneous fistula after total laryngectomy with particular focus on nutritional status. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2015;35: 243–248.

- Guimarães AV, Aires FT, Dedivitis RA, Kulcsar MAV, Ramos DM, Cernea CR, et al. Efficacy of pectoralis major muscle flap for pharyngocutaneous fistula prevention in salvage total laryngectomy: A systematic review. Head Neck. 2016;38 Suppl 1: E2317–21. [CrossRef]

- Gendreau-Lefèvre A-K, Audet N, Maltais S, Thuot F. Prophylactic pectoralis major muscle flap in prevention of pharyngocutaneous fistula in total laryngectomy after radiotherapy. Head Neck. 2015;37: 1233–1238. [CrossRef]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69: 7–34.

- Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Parkin DM, Piñeros M, Znaor A, et al. Cancer statistics for the year 2020: An overview. Int J Cancer. 2021. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).