1. Introduction

Digital transformation is currently ongoing with an increased pace, particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic, during which citizens and organizations were forced to accelerate digital technologies’ adoption and integration [

1,

2]. Such rapid change requires all organizations to adapt the way they operate and deliver value to customers. This is obviously also the case of the public sector, in which organizations intend to become more modernized, closer to the needs of citizens, taking advantage of the full potential of digital technologies [

3,

4]. This endeavor is a very demanding one, since public services are constantly being challenged to improve service delivery, with less bureaucracy and more openness in interactions, in a timely and responsible manner and minimizing administrative costs, which are financed by citizens’ taxes.

Digital transformation in the public sector, however, can become slow and complex when workers have lacking skills. Considering that formal education takes too long to adapt curricula and, afterwards, to provide the labor force with digitally-skilled workers, training the active population and, particularly workers in the public sector, is paramount do address the digital skills’ shortage [

5]. In fact, through training, organizations are able to empower workers with the desired skills and knowledge which will contribute to reinforce productivity [

4,

6]. Additionally, and according to the endogenous growth theory developed, for example, by Robert Lucas [

7], physical capital, human capital and technology are complementary, which means that the effect of technologic advances, like those related with digital transformation, on productivity and growth is leveraged when accompanied by the reinforcement of physical resources as well as the adequate reskilling of human resources.

Being aware of these challenges, the European Council and the Commission have defined digital transformation as a strategic path to guide Europe’s development in the upcoming years. Accordingly, planned investments and reforms under the Recovery and Resilience Facility dedicate 46 billion euros to the area of digitalization of public services and government processes [

2]. In Portugal, the national context of the present study, the Recovery and Resilience Plan (RRP) defined a specific component related to Empowerment, Digitization, Interoperability and Cybersecurity in public administration, with a foreseen investment amount of 578 million euros, of which 86 million euros are dedicated to public servants’ training and capacity building [

8].

Considering the increased political relevance attributed to digital transformation and training in the public sector, studies that contribute to help organizations understanding the major digital needs and who tends to participate more in professional training in the digital field, are essential to facilitate and to make the process of digital transformation more efficient.

In such context, the main goal of this research is to investigate, in the Portuguese public sector, which professional and demographic characteristics are related with the attendance of professional training in general and, particularly, in the digital field. Additionally, we aim to relate the level of digital competencies of public sector workers with their perceived training needs in digital tools. Finally, and considering the importance of workers’ motivation to participate in training, it is also a purpose of this work to identify the main benefits of training in the participants’ perspective.

This paper relies on the human capital theoretical framework, namely the seminal works of Becker [

9] and Mincer [

10], to empirically study training incidence and training perceived benefits (from the workers’ perspective). In spite of the consolidated literature concerning training incidence determinants, for instance in [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18], the application of it to the specific fields of the public sector and of the training in digital skills has been somewhat neglected. Additionally, although there is an increasing amount of literature devoted to the importance of digital transformation in the public sector, with recent examples such as [

1,

19,

20], the majority of studies has tended to rely mainly on case studies, analyzing their processes and implementation success factors, without paying sufficient attention to the crucial role of workers’ training on those processes. Recently published systematic literature reviews covering the theme of digital transformation in the public sector, make it evident that the specific topic of workers’ training has been overlooked [

3,

21-

22]. Hence, this paper intends to address this literature gap, developing a study on training incidence and training benefits, with a particular approach to digital training, and applying it to the specific context of the public sector.

The adopted methodology consisted of a quantitative approach, using primary data. The instrument used to collect the data was the survey by questionnaire, available on several online platforms. 618 responses were obtained, of which 573 were considered complete and therefore validated. Based on the human capital theory, a probabilistic regression model was used to relate several workers’ and job characteristics, such as education, age, marital status, parenthood, job tenure, professional qualification, type of professional contract and subsector, with the likelihood to participate in training in digital and non-digital fields.

The paper is organized in the following way: after this introduction, previous theoretical and empirical contributions on this topic are reviewed. The third section presents the data collection instrument and the model specification. Next, the results obtained from models’ estimations and statistics related with digital skills, training needs and training benefits are discussed and, finally, the conclusion section closes the paper.

2. Theoretical Framework and research hypotheses

The term digital transformation in public sector is generally understood as a strategic mechanism of change which, through the use of digital technologies, allows public administration to improve interactions with users, leading to a more efficient and effective public service, with higher value creation for citizens and organizations [

1,

3,

23]. Digital transformation is currently an endeavor for governments all over the world, that try to keep up with the tremendously fast development of new information and communication technologies, moved by several motives: improve efficiency in resource use and service quality, increase users’ access, inclusion and participation, enhance accountability and transparency, and, through a better service deliver, improve the governments’ image and public trust [

20,

21]. The principle of user-centered digital services – putting the needs of citizens and organizations at the heart of public sector reforms – is the main element that characterizes the paradigm shift that has been occurring from the earlier stages of e-government – mere online presence, provision of information, online interactions and transactions – to digital transformation [

19,

23].

In spite of the numerous programs implemented by governments worldwide to boost progress towards digital transformation, according to the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) produced by the European Commission, progress has been uneven across EU countries and “services for citizens are less likely to be available online when compared to services for businesses” [

2] (p.3). DESI is a composite index which accounts for 5 sub-dimensions within the dimension of digital public services: i) e-government users, measuring the percentage of internet users that use it to interact with the public services; ii) availability of pre-filled forms, following the “once only” principle; iii) digital public services for citizens, provided online, through a government portal; iv) digital public services for businesses, measuring the degree to which those services are interoperable and work cross-border and v) the government’s commitment to open data policy. In 2021, Portugal ranked in the 14th position, scoring 67.9/100 and being aligned with the EU average. Such overall score results from the fact that Portugal scores slightly above the EU average in all sub-dimensions, except in the one related to open data, in which the Portuguese score is the 5th worst among European countries [

2].

The Portuguese government has implemented several programs designed to improve digitalization of public services, which recently received an investment boost related to the implementation of the national RRP. In this context, the specific capacity building program “AP Digital 4.0” should be highlighted, since it is specifically designed to train public sector workers and leaders for digital transformation, based on the understanding of emerging technologies, such as the management of big data, algorithms, digital innovation, robotics, artificial intelligence and cybersecurity, aiming to train above 60,000 public servants until 2025 [

24]. However, more basic competencies concerning established information and communication technologies might also lack in public sector workers, justifying a general approach to capacity building, in order to narrow the gap between existing and needed digital competencies. The Citizens' Digital Competence Framework, known as DigComp (updated in 2022), identifies key areas of digital competence, serving as a reference for EU-wide policymakers in this field of building digital competences through education and training initiatives. In this framework, digital competencies are grouped into five areas: Information and data literacy; Communication and collaboration; Digital content creation; Safety; and Problem solving. Each competence area is then broken down into more specific competencies [

25]. This European framework, complemented by the recent literature review provided by [

26] and by experts’ consultation, was used to define digital competencies used in this study.

According to the human capital theory, the decision of investing in human capital – either formal education or training -, is made when the present value of future expected benefits exceeds the current (direct and opportunity) costs associated to that investment [

9]. In the case of training and when it is from the organization’s initiative, costs include those directly related with training provision and the foregone productivity associated with on-the-job hours spend in training sessions; the benefits are mainly related to future workers’ productivity gains. From the employee perspective, the assessment of benefits is concerned with the expected consequences of training skills attainment on wages and career development prospects [

16]. Previous literature generally points out that the benefits outweigh the costs (in [

27], for example, positive internal rates of return were obtained for both organizations and workers) which leads to training offered and participation. However, the expected benefits and costs of training might depend on workers and job characteristics, thus, the probability of participation in professional training may be unevenly distributed across different groups of workers.

Regarding the influence of individual attributes on training incidence, the education level assumes a prominent role. The likelihood to participate in training has been positively related to the worker's level of schooling by a vast number of empirical studies [

11,

12,

28,

29,

30]. This relationship, supported by the human capital theory, relies on the argument that workers who have a greater learning capacity may be able to make better use of the knowledge taught (absorptive capacity), increasing the efficiency of training [

10,

11,

31]. In fact, formal education is seen as “a complementary factor of training at work in the production of human capital” [

10] (p.10), with this complementarity being associated with the achievement of higher levels of productivity.

Although the dominant literature corroborates a positive relationship between education level and training incidence, past findings are not completely consensual. For instance, a negative relationship between education level and training was obtained in [

15] and [

18]. The former authors justify their results arguing that, when the decision is made autonomously by the worker, the expected marginal benefits (in terms of wage differential or career prospects) will be higher in the case of workers with less formal education while the latter claims that this negative relation occurs because firms use workplace training to close the gap between the competencies needed for the job and the ones already attained by the worker. Nevertheless, in this research we followed the majority of the literature in forming our hypothesis of a positive relationship between education level and training. We recognize, however, that the current context is extremely distinct from what it was years ago: skills requirements, particularly, digital skills, are changing at a much quicker pace than before, thus justifying a new study to confirm (or not) previous results.

Moreover, qualification level or occupational category has been proven to influence training participation, as higher ranked qualification levels may require more demanding competencies and skills [

16]. [

15] show that the likelihood of participating in non-mandatory training is higher for workers holding a higher hierarchical position. Accordingly, [

28] find that training participation is higher in more skilled workers, being this applicable to the public sector. In their recent study, [

5] conclude that workers with higher qualification levels (“white-collar” as opposed to “blue collar”) present a higher probability of receiving training.

Supported by the previous arguments, we hereby establish the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1a. Professional training incidence is positively related with worker’ education level.

Hypothesis 1b. Professional training incidence is positively related with worker’ professional qualification.

Similar arguments associated to the human capital model have been put forward to negatively associate worker’s age and/or job tenure with professional training participation [

12]. According to [

9], it is expected that younger professionals receive more on-the-job training than older people, since the return on investment is higher the longer the worker is expected to stay in the company. In developed countries, that are dramatically recording an ageing active population, this potential negative effect of age is certainly worrying, since it may inhibit the necessary upskilling and reskilling of workers, particularly in face of digital transformation processes [

32]. The negative impact of age on training incidence has been confirmed by several empirical studies (e.g. [

18], analyzing participation in employer-sponsored training, and [

15,

17], applied to non-mandatory training). The study of [

5] also supports this negative effect of age, which holds even after including variables that control for workplace features. A slightly different result was found in [

28], where an inverse U-shaped relationship between age and training participation was identified, meaning that in earlier ages participation is lower, increasing after a few years of job experience and decreasing in older workers. In [

12] age and job tenure are both used as potential explanatory variables of training participation, among other employee and employer characteristics, concluding that the influence of age is not statistically significant; yet, job tenure is found to have a significant and negative effect. Age and job tenure were both considered in [

33], evidencing that, in the case of public sector, age does not have a significant effect, while job tenure has a significant and negative influence in training propensity.

Based on the above, it is intended to test the following research hypotheses, testing the effect of age and job tenure separately:

Hypothesis 2a. Professional training incidence is negatively related with worker’ age.

Hypothesis 2b. Professional training incidence is negatively related with job tenure of the worker.

The study upon the influence of gender in training incidence can also be framed within the human capital model, under the argument that it is not gender, per se, that determines propensity to engage in training initiatives (either employer or employee-sponsored), but rather the degree of job attachment and expected tenure [

34]. Under such argument, and considering the still existing gender discrimination concerning family care responsibilities, it could be expected that females are more subject to job interruptions, thus decreasing the likelihood of both employers and female employees themselves to invest in training efforts [

14]. Another possible explanation relies on the gender segmentation that prevails in labor markets: more demanding occupations and industries in terms of continuous upskilling (i.e.: technological-related) tend to be held mostly by men, hence justifying a higher participation of males in job-related training [

15]. These arguments support the findings of empirical studies that negatively relate female gender with training incidence, such as [

12] and [

28]. But when other variables, such as professional qualification, businesses sectors and parenthood, are included in the model, different results may be found.

Some authors have concluded for an opposite influence of gender on training incidence. According to [

35], the circumstance of often job breaks that affect more women may actually instigate them to use work-related training opportunities to catch up and close the skills’ gap. In the study carried out by [

36], women demonstrate a higher attendance of training sessions than men and have general more positive attitudes towards training. The author explains this relationship by considering that “training is more beneficial due to the technical nature of the work functions that are being placed on women (who may not feel prepared for these functions)” [

36] (p.9). [

15] also found that women are more likely than men to participate in non-mandatory training. Similar results were found in [

14], even controlling for other employer and employee features. [

5] also test for the influence of gender on the likelihood of receiving training, but the results for this variable were not statistically significant.

Hence, the following hypothesis is established for empirical testing:

Hypothesis 3. Professional training incidence is determined by gender, being higher in female workers than in men.

Work stability also has a potential influence on training incidence. Organizations are more willing to invest in training of workers with longer employment contracts, since they guarantee a greater return than the investment made in workers with temporary contracts. The predisposition of workers or organizations to bear training costs is intertwined with the likelihood of labor turnover [

9]. From the perspective of [

10], workers who receive training in the workplace are those who have lower turnover rates, since training aimed at increasing the skill and productivity rates of an organization is not fully applicable in other organizations. For this reason, it is expected that workers with more precarious contractual ties, and therefore with a higher turnover rate, have less training than the remaining [

16]. This theoretical rational has been tested empirically in studies such as [

15] and [

18], who posit that full-time employees are more prone to participate in training than part-time employees. However, results obtained in those studies did not fully corroborated this hypothesis. In their research comparing the public sector with the private sector regarding training incidence, [

33] validate the positive influence of permanent contracts in both sectors.

Hypothesis 4. Professional training incidence is positively influenced by labor contract stability of workers.

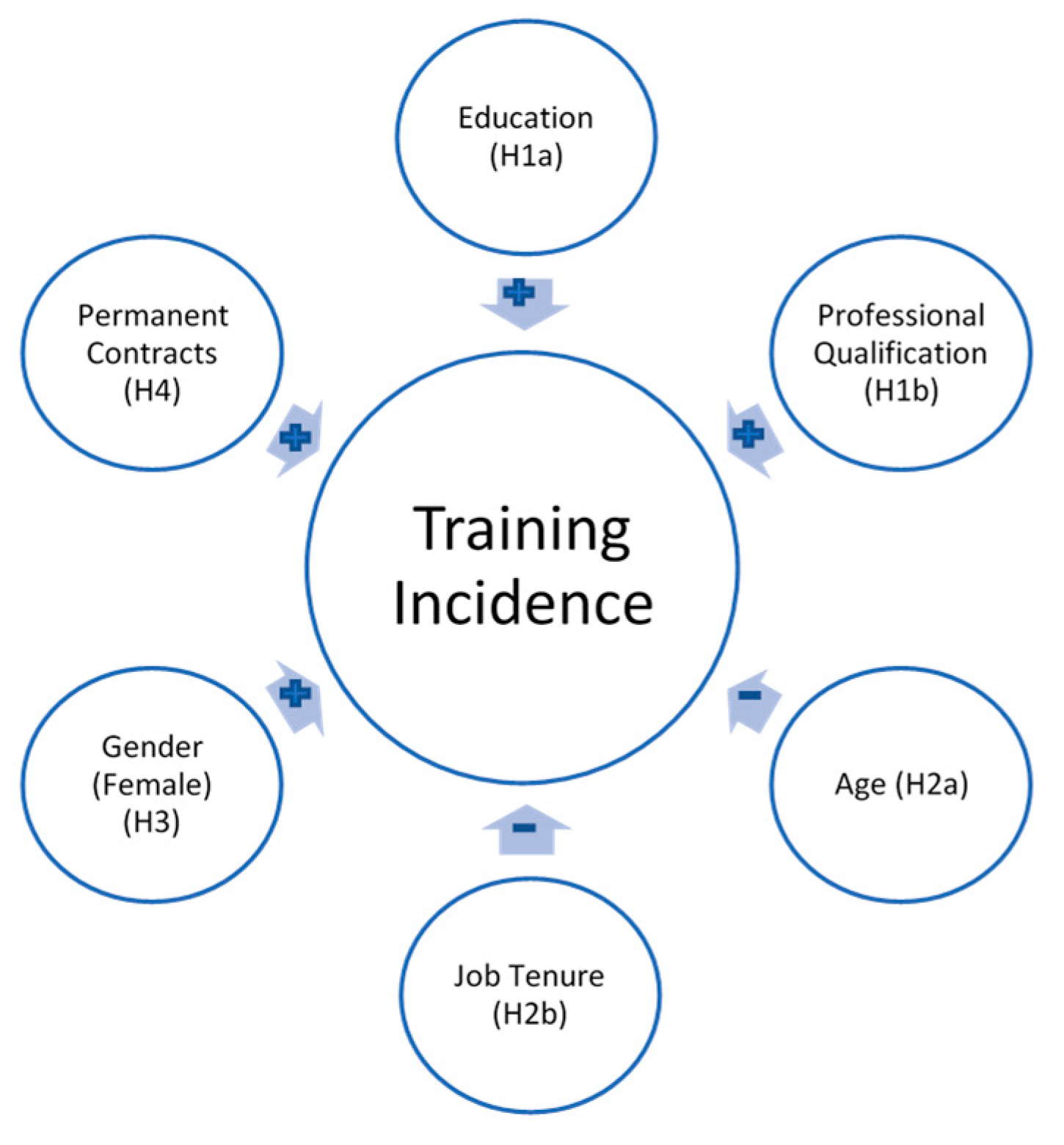

Although there is a vast literature relating individual characteristics with training propensity, little is known about this relationship for the specific case of training in the digital field. Thus, we aim to contribute to the emerging literature on digital learning, by testing the abovementioned hypotheses in both cases of training in digital and non-digital fields, through the conceptual model presented in

Figure 1. Additionally, and by following other contributions, such as those of [5, 18, 28], we opted for including other potentially relevant variables in the empirical model to accurately capture the influence of each determinant. Thus, control variables like marital status, parenthood, and public subsector were also considered.

3. Materials and Methods

Data collection relied on primary data, obtained through an online questionnaire. Such method for data collection is particularly suited when information to be gathered is compatible with rather standardized and closed questions and when there is a wide geographical area to be covered. This was the case of this study, aiming to collect information and perceptions of the nation-wide public sector workers on their professional training and considering the inexistence of secondary data with the variables needed to test our hypotheses. Other advantages attributed to online questionnaires include their ease and low cost to be administered, fast delivery and the fact that respondents may answer when and where they wish, at their convenience, within the deadline indicated [

37].

Given the novelty of this specific topic – digital training in the public sector – we could not identity a previously implemented questionnaire with a similar object of interest, which could be adopted or adapted in this study. Thus, all questions were developed from scratch, but based on the relevant literature and experts’ opinions and having in mind the variables needed to test our hypotheses.

The questionnaire included four sections, following an introduction that aimed to clarify the scientific objectives of the survey, provide the necessary information regarding anonymity assurance and obtain the respondents’ consent to use the obtained data, exclusively for academic purposes, applying a macro-level analysis. In the first section, information about training incidence and training benefits was asked, considering the previous two years. Incidence of training was distinguished between training in general and in the digital fields; between organization- and worker-initiative and between on-the-job and off-the-job training. A perception of the importance of training sessions for 12 potential financial and non-financial benefits was also inquired, considering a 1-5 Likert scale (with 1 corresponding to “no contribution” and 5 to “high contribution”). The potential benefits considered were: Wage increase; Career progression; Techniques actualization; Improvement in general competences; Productivity/performance improvement; Adaptation to new tasks; Improvement in legal domains; Improvement in software manipulation; Better relationship with citizens; Improvement in foreign languages; Better relationship with peers; Better relationship with chiefs (a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.86 was obtained revealing a good internal consistence). Then, a variable (perceived training benefits) was determined by the average of the level of importance attributed to each training benefit and corresponds to a proxy of the value each worker gives to professional training.

In the second section, each worker was asked to classified their knowledge in 12 digital competences, using a 1-5 Likert scale between “no qualified” and “highly qualified”. These digital competencies were defined by combining information obtained from the DigComp framework, from existing training programs for public administration in digital tools and through experts’ consultation (particularly, with the contribution of three higher education professors, who also collaborate with the public sector in specific digital training programs). The list of the 12 digital competencies includes: Word; Excel; Software for presentations; Internet and email; Communication systems; Dataset management; Big data management; Cybersecurity; Social media; Cloud technology; Web pages construction; and Video/images edition (and the internal consistence is excellent considering a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.92).

In the third part, the respondents were asked to identify their training needs in the digital fields by classifying the importance (from 1-“nothing important” to 5-“extremely important” in a Likert scale) of having training in the 12 digital competences used in the previous section (Cronbach’s alpha of 0.90).

In the last section, demographic and professional information was requested, namely: gender, age, schooling, marital status, parenthood, residence county, occupation, job tenure, type of professional contract and public subsector.

After being submitted to a pre-test by human resources’ specialists working in distinct subsectors of public services and having made the necessary adjustments, the questionnaire was sent by e-mail for several public organizations in the whole country: Local Government entities, Employment Offices, Social Security Offices, Schools, Courts, Fiscal Offices and Public Hospitals and was posted in social media. The answers were collected for a month, between 11 November and 16 December 2020. Complete information was obtained for 573 workers.

The participants' answers were extracted from the Google Forms platform through an Excel file. After this procedure, the data were exported to Stata software in order to estimate models and other relevant statistics. In

Table 1, some summary statistics are presented considering the sample distributed between three groups of workers:

(a) No-training group (including all the individuals that referred not having participated in training over the last two years) with 132 workers - Column 1;

(b) Non-digital training group (those that had participated in training sessions, but not in the digital fields) with 281 workers - Column 2;

(c) Digital training group (those that had participated in training sessions in the digital fields) with 160 workers - Column 3.

Although we did not apply a probability sampling technique, preventing us to make statistical inferences about the population’s characteristics, our sample statistics are very similar to statistics of the population of Portuguese public service workers considering its composition according to gender, age and job contracts. Regarding the education level, our sample composition reveals a higher weight of highly educated people, when compared to the generic profile of public sector workers. In order to evaluate results’ sensitiveness to this mismatch, we compared the results obtained by estimating the model for different subsamples.

The majority of workers are female and this proportion is especially high in the second group – workers with training in other fields than digital. The average age is around 46 years old and slightly higher for those who participate in training. Education is measured by years of schooling, and the average is closer to the number of years that corresponds to an undergraduate degree. Also, schooling years are higher in case of the last group of workers, suggesting that workers with higher levels of schooling participate more in training in the digital fields. Workers in this third group are more often married and have higher job tenure.

Professional qualification is a variable with values between 1 to 6, that was constructed by considering worker occupation (for example, the value 1 was attributed to operational assistants, 2 to technical assistants and 6 to local government representatives). This variable is related with skills acquired at work, and since its average is higher in column (3), this might suggest a positive relation between digital training and job-specific skills. Permanent contracts are predominant among workers in the sample (88% in the whole sample) with the percentage of temporary workers being higher in the group of non-trained workers (15.2% against 10.6% and 12.5% in columns (2) and (3)).

The distribution of workers between public subsectors is also very different between columns (1), (2) and (3), which might be associated with greater/lesser willingness to participate in training from workers/organizations in different subsectors. Clearly, local administration has a high weight in the sample, but this percentage is lower between workers who participated in training in the last two years and even lower when only training in the digital field is considered. On the other hand, workers in the finance subsector correspond to 28.8% of total workers that had trained in digital fields, a much higher percentage than its importance in the total sample, which also occurs with workers in the education subsector.

For workers that had participated in non-digital training, the average is of 3.8 participations in the last two years, while for those that participated in training in digital tools, the average is higher and corresponds to 5.4. On-the-job training has a higher percentage between the group of workers that had digital training and self-initiative participation is higher in non-digital training, suggesting that public organizations recognize the importance and promote training in digital fields more often. Finally, workers that had participated in training in digital fields recognize more benefits from training than those in general (non-digital) fields.

In accordance with the literature (e.g. [

5]), we use a linear probability model to estimate a binary variable

that will be =1 if worker i participated in training sessions over the last two years and =0 otherwise:

corresponds to a set of personal characteristics of worker i as gender (=1if female, =0 if male), age (in years), schooling (in years), marital status (=1 if married, =0 otherwise) and parenthood (=1 if the individual has children, =0 if not). is a vector that identifies professional characteristics of worker i like professional qualification (a variable with values between 1 and 6, where 1 corresponds to the lowest qualification); job tenure (in years); and public subsector (education, health, justice, finance, social security, other subsectors and local administration which is the baseline category).

Then, a similar model is used to investigate how personal and professional characteristics influence the probability of participating in training in the particular case of digital fields

:

3. Results

3.1. Competences and training needs in digital fields

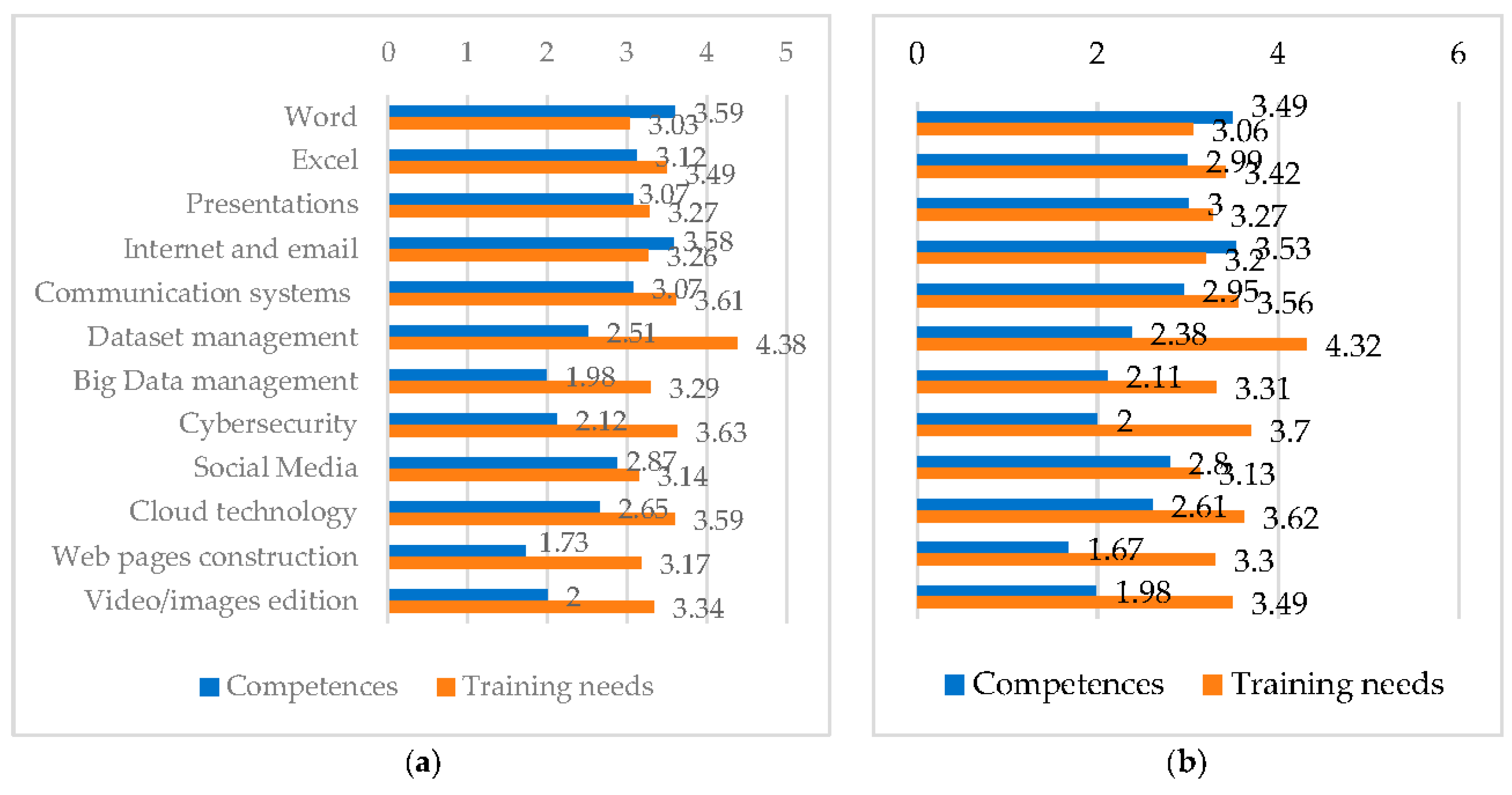

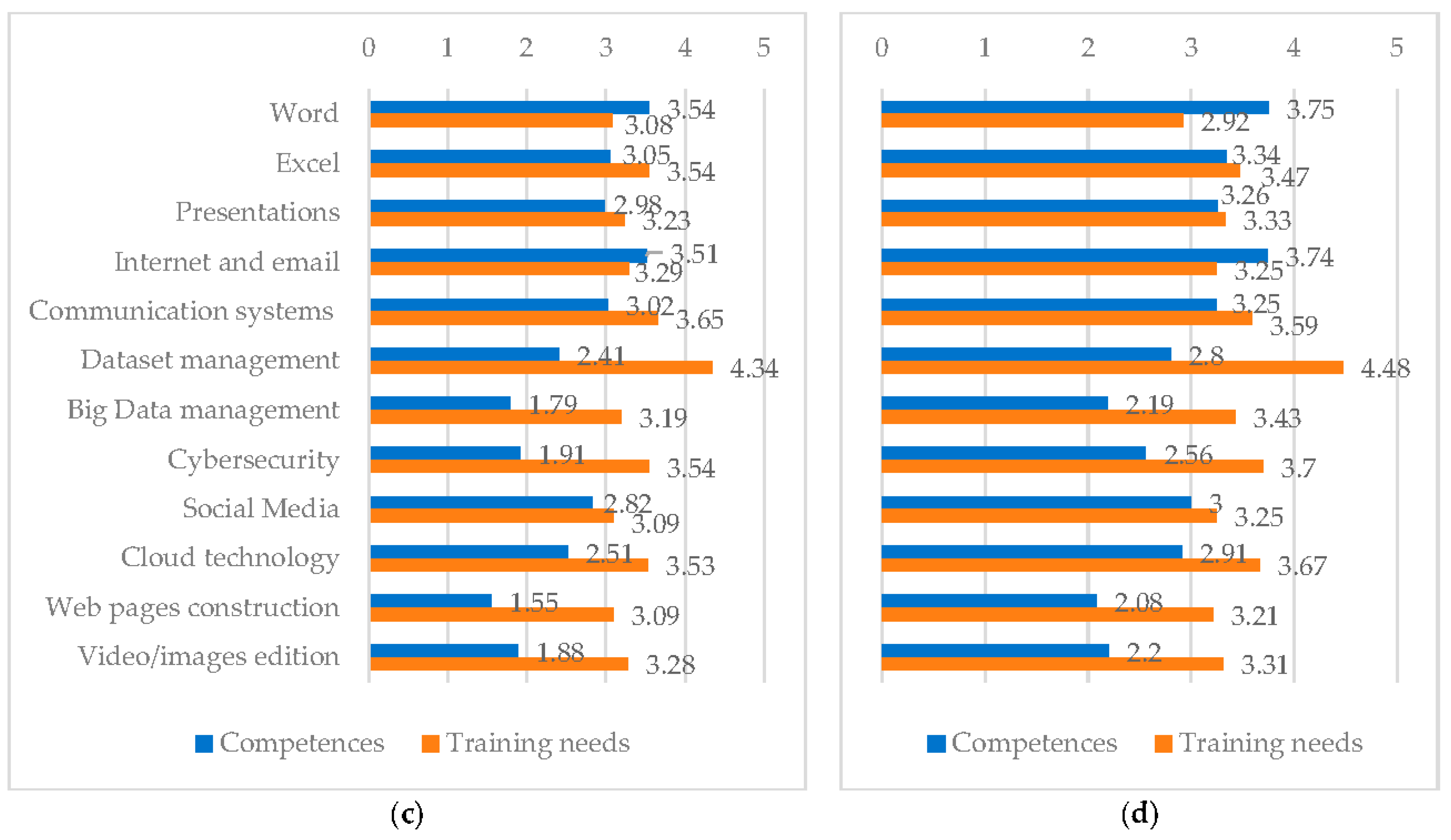

In

Figure 2, the competences in the digital fields perceived by workers as well as their training needs are presented for the whole sample and for the three groups of workers. The respondents classified their digital literacy between the basic and the intermediate level (average = 2.70 in a 1-5 scale). Word, (3.59), Internet and email (3.58) and Excel (3.12) are the competences with highest average values of perceived knowledge. On the contrary, workers consider to have lower knowledge in the Construction/management of web pages (1.73), in the Big data management (1.98) and in Image/video editing (2.00). When the sample is separated by groups, the same competences are pointed as those with the highest and lowest level of perceived knowledge (and in case of the “no-training” group also Cybersecurity is included in the list of the lower competences), but the average level of perceived knowledge of the digital training group is significantly higher than the average level of the other two groups (with particularly higher values for Dataset and Big data management, Social media and Cloud technology).

In relation to training needs, the higher average value is in the case of Dataset management (4.38) – this clearly indicates the importance that workers give to this competence since it is not in the list of the lowest knowledge. For those that have already had training in digital fields, and although recognizing a higher knowledge in Dataset management than the remaining workers, this competence is even more valued - the average of the importance of training in this skill is of 4.48. Although not presented in

Figure 2, further analysis of our dataset allowed us to conclude that this training need is especially high in the subsectors of health and social security.

Also, by comparing previous knowledge with training needs, it seems that training in Communication systems is valued as a means to reinforce the knowledge already attained, whereas training in Cybersecurity is also considered to be very important (particularly, in the subsectors of justice and health), but, in this case, in order to overcome the weak knowledge revealed by the workers. In contrast, Web pages construction and Video/images editing are not very important in the perspective of workers in the public sector since, even though they recognize low knowledge, they do not spot high training needs in this field. Finally, training needs are low in case of Word and Social media, which could be explained by the higher values presented for the perceived knowledge in these fields.

Interestingly, the group that gives more importance to future training in the digital field is the digital training group (that had already acquired some skills in this field) which might be due to these workers being able to recognize more benefits to training. In order to investigate this possibility, in

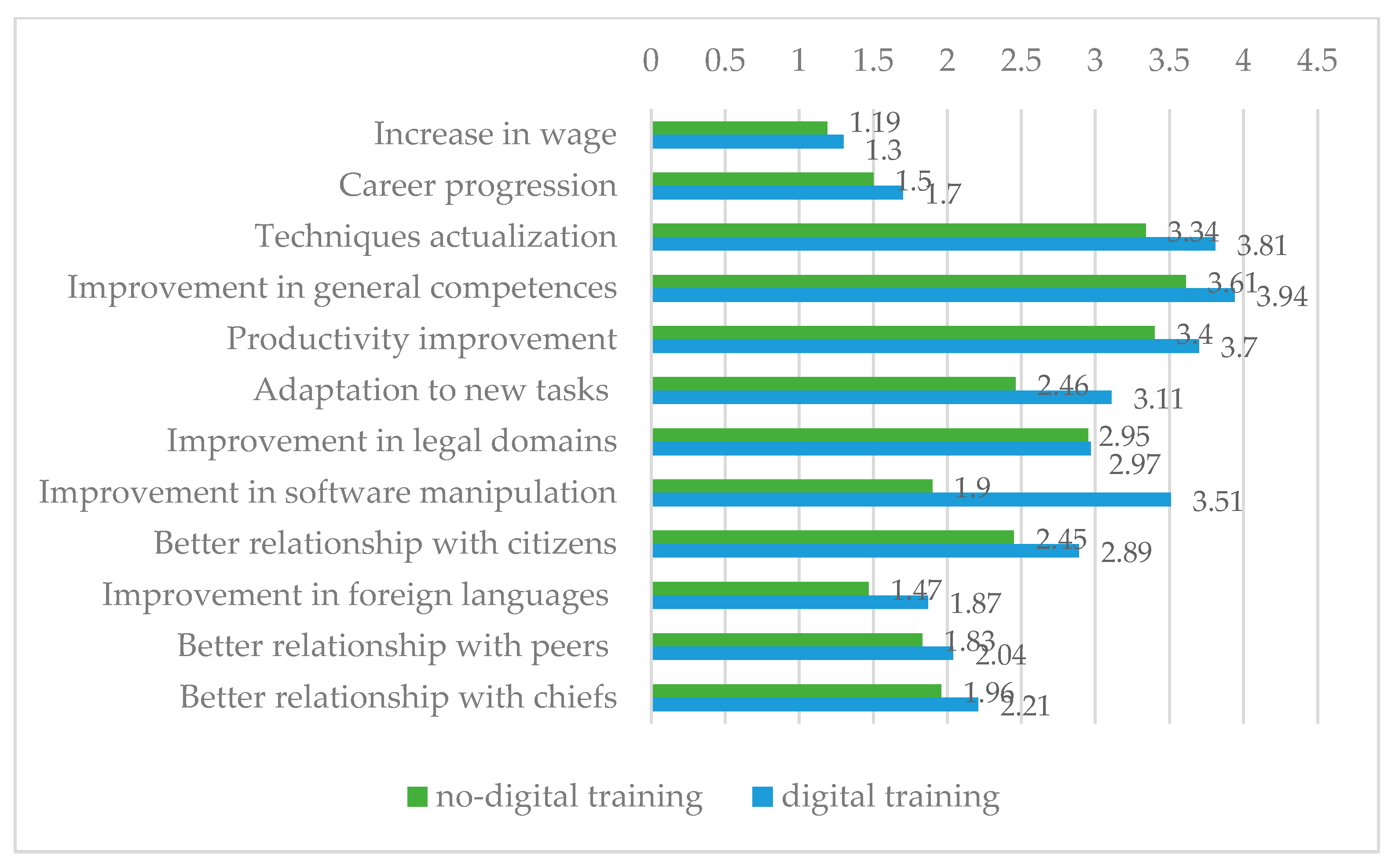

Figure 3, we present the average of the perceived contributions of training to the various potential benefits for the “non-digital training” group and the “digital training” group.

3.2. Perceived benefits of training

Professional training contributes mainly to the improvement of skills in general, to the updating of techniques and the improvement of the worker's performance/productivity. In turn, the workers in the sample express that participation in training has little or no contribution to wages increases, career progression and to improve communication in foreign languages.

Comparing the two groups of workers, we conclude that the digital training group perceives a higher value from all the potential benefits of training than the other group. As expected, considering the type of training received, differences are especially higher in case of improvement in software manipulation, but also higher in case of adaptation to new tasks, techniques actualization and the contribution to improve the relationship with citizens. Although not observable in

Figure 3, we also note that workers who take the initiative to participate in training are those who mostly value the contributions of professional training.

3.3. Models’ estimation - Propensity to participate in professional training

In

Table 2, we present the results obtained by estimating equation (1) – Column (1) and equation (2) – Column (2). The log-likelihood ratio with a p-value<0.001 indicates that some demographic and professional variables of workers influence their propensity to participate in professional training and the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) tests (average of 1.35 and a maximum value of 2.29) point to the inexistence of multicollinearity problems.

In relation to schooling, the results are in line with previous authors, who argue that workers with higher levels of education are those who are more involved in training, pointing to schooling and training as complementary [

5,

10,

11,

12,

28,

29]. Thus, Hypothesis (1a) is verified and for both types of training – in digital and non-digital fields. On the other hand, professional qualification seems to be determinant for the incidence of digital training, but not significant for non-digital training, partially confirming Hypothesis (1b). Therefore, complementarity between training and job-specific skills is more important in the case of the digital field.

Neither age and job tenure are significant determinants for the incidence of training. In the case of job tenure, a deeper analysis allowed to observe that workers with higher tenure in organizations take the initiative to participate in training more often than recent workers (which may show the willingness to be up-to-date), while organizations tend to offer training especially to apprentices and other newcomers in order to prepare them for their occupations. These two effects balanced each other and may justify the non-significance of the coefficient of tenure in the probability of training. Thus, Hypothesis (2a) is not validated, but Hypothesis (2b) is partially confirmed as organizations are more prone to offer training to recent workers.

Also, according to

Table 2, we observe a higher propensity to participate in professional training in case of female workers but only in the non-digital field, which partially confirms Hypothesis (3). This is in line with [

36] investigation, that justify this result by claiming that women have a more positive attitude towards training than men, and with the findings of [

15] and [

14].

Generally, the literature indicates that workers with more precarious employment contracts participate less in training, since organizations are less willing to invest in workers with a weak bond with the institution [

10]. However, the non-significant coefficient obtained to the temporary contracts may be explained by considering the particularities of public sector, namely the fact that training is, in the Portuguese public administration system, a condition to obtain a permanent contract. In fact, if we estimate an alternative model where the intensity of training (number of sessions) is used as dependent variable instead of the incidence (and considering the same set of explanatory variables), we obtain a positive coefficient for workers with temporary contracts, which contradicts Hypothesis (4).

Considering the statistically significant and positive coefficients of the finance subsector in columns (1) and (2), we conclude that individuals in the sample who work in this subsector are more likely to attend professional training, both in the digital and non-digital fields. If we take into consideration the information on the self/organization-initiative to participate, we observe that this higher propensity to train is particularly evident in organization-initiative training. In other words, organizations from the finance subsector offer training to their workers more often than other public subsectors. Social security workers are also more propense to participate in digital training than the workers from the remaining subsectors.

Finally, equation (2) was also estimated by including the variable of the perceived training benefits in order to understand if workers who recognize higher training benefits have a higher probability of participating in digital training (among workers who participate in training). A positive and statistically significant coefficient for this variable was obtained, confirming the importance of motivation in training incidence for the particular case of the digital field.

4. Discussion

The focus of this study relied on training incidence and training benefits, addressing particularly digital training, in the specific context of the public sector. 72% of the public sector workers that answered our questionnaire had not participated in training in the digital field in the last two years. This is a worrying observation, especially when combined with their own perception of a low level of knowledge in digital domains (between the basic and the intermediate level) which forces the adoption of rudimentary procedures in the execution of certain functions, leading to a lack of effectiveness and efficiency in work performance.

Therefore, the promotion of training programs in a regular basis by organizations and the incentive to participate in training sessions in the digital field (using mechanisms to reward workers for their participation) is essential to enhance the digital competences of public sector workers, and better prepare them for the digital transformation process, already ongoing. Workers participation might also be triggered by the dissemination of training benefits, as workers’ perception of these benefits seems to be an important motivator for participating in training in digital tools.

Nevertheless, the results of our study are encouraging since the majority (87%) of respondents reveal a willingness to participate in training in the digital field in the future and recognize significant training needs in this field. Particularly, the workers in the sample show significant interest in participating in training in Dataset management and Communication systems, to reinforce prior knowledge, and in Cybersecurity, to fulfil in the knowledge gap in this dimension.

On the relation between acquired skills and training needs, we observe a negative correlation for the most basic competences (less knowledge, greater need for training), and a positive correlation for the more advanced digital domains (like Database management; Big data management; and Website construction) suggesting that, in this case, those who know more are more interested in reinforcing their knowledge.

This investigation also sought to study the relationship between demographic and professional characteristics and the propensity for professional training through a probabilistic regression model. One of the main results obtained, both for training in digital and non-digital skills, is the evidence that training does not act as a substitute for formal education, but rather as a complement to the knowledge obtained through schooling. In fact, high qualified and educated workers (and with higher levels of digital skills) had participated more in training and showed greater interest in participating in training in the future, especially in more advanced domains. This raises an important issue concerning employees with lower human capital levels (lower schooling and / or lower qualification levels): their reduced participation in training may result in widening the skills gap, with inherent risks for the organization and the workers themselves. Possible interventions to contradict such risk include, on the one hand, putting in place motivating incentives to participate (such as public recognition, financial rewards or consideration for career progression) and, on the other hand, designing appropriate training strategies with a sequential approach to contents’ demand, so that workers with lower educational levels are able to follow and benefit from training.

The results revealed that female workers tend to attend more training sessions in non-digital training than men, but not in the digital fields. A positive relationship was obtained between job tenure and participation in training sessions by worker initiative, which might countervail the higher propensity of organizations to provide training to newer workers. Subsectors are also important determinants of the incidence of training, with finance and social security workers having higher propensity to participate in training in the digital fields.

Our investigation extends human capital theory to the specific field of digital knowledge and it provides information on training of workers in the public sector, which is essential for public organizations to better prepare for digital transformation. Information concerning the groups that participate more in training may support policymakers to focus their efforts towards less participating groups. Given the methodology used – survey by questionnaire – it was possible to obtain a significant amount of information and consider the opinion of a very large number of participants. Although a non-probability sampling technique was adopted, preventing us to make statistical inferences about the population’s characteristics, our sample statistics are very similar to statistics of the population of Portuguese public service workers considering gender, age and job contracts. Non neglectable differences were observed concerning the education level, but when models are tested considering different subsamples to overcome this limitation, we obtain robust results, suggesting that they are not very sensitive to this mismatch. However, a possible enlargement of the database, as well as the extension of the study to the private sector (where the process of digital transformation is also of increasing importance), allowing comparisons between the private and public sectors, are suggestions for future investigations.

Supplementary Materials

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Individual contributions of the different authors of this article occurred as follows. Conceptualization: Ana Lopes and Joana Farto; Methodology: Ana Lopes, Ana Sargento and Joana Farto; Formal analysis (statistical techniques): Ana Lopes and Ana Sargento; Investigation (data collection): Joana Farto; Writing (original draft preparation): Ana Lopes, Ana Sargento and Joana Farto; Writing (review and editing): Ana Lopes and Ana Sargento; Visualization (results’ presentation): Ana Lopes; Supervision: Ana Lopes. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by UIDB/04928/2020-FCT–Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

This paper is financed by National Funds of the FCT – Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology within the project “UIDB/04928/2020”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bondarenko, S.; Liganenko, I.; Mykytenko, V. Transformation of public administration in digital conditions: world experience, prospects of Ukraine. J. Sci. Pap. Social Dev. Secur.I 2020, 10(2), 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission, Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) 2022 - Digital Public Services 2022. [Online]. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/digital-economy-and-society-index-desi-2021 8 (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Alvarenga, A.; Matos, F.; Godina, R.; Matias, J. Digital transformation and knowledge management in the public sector. Sustain. 2020, 12(14), 5824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, Z.; Rainayee, A. Examining the Mediating Role of Person–Job Fit in the Relationship between Training and Performance: A Civil Servant Perspective. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2019, 20(2), 529–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, M.; Gomez, R.; Kaufman, B.; Wilkinson, A.; Zhang, T. Is it ‘you’ or ‘your workplace’? Predictors of job-related training in the Anglo-American world. Int. J. Train. Dev. 2020, 24(3), 173–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stofkova, J.; Poliakova, A.; Stofkova, K.; Malega, P.; Krejnus, M.; Binasova, V.; Daneshjo, N. Digital Skills as a Significant Factor of Human Resources Development. Sustain. 2022, 14(20), 13117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, R. On the mechanics of economic development. J. Monet. Econ. 1988, 22(1), 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Governo de Portugal, “Plano de Recuperação e Resiliência - Componente 19 - Transição Digital da Administração Pública: CApacitação, Digitalização, Interoperabilidade e Cibersegurança.,” 2021. Available online: https://dados.gov.pt/s/resources/documentacao-do-prr/20210502-190342/39-20210421-componente19vf.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- Becker, G. Investment in Human Capital: A Theoretical Analysis. J. Polit. Econ. 1962, 70(5), 9–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mincer, J. Human capital, technology, and the wage structure: what do time series show? Stud. Hum. Cap. 1991, 3581, 366–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altonji, J.; Spletzer, J. Worker characteristics, job characteristics, and the receipt of on-the-job training. Ind. Labor Relations Rev. 1991, 45(1), 58–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazis, H.; Gittleman, M.; Joyce, M. Correlates of Training: an analysis using both employer and employee characteristics. Ind. Labor Relations Rev. 2000, 53(3), 443–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Icardi, R. Does workplace training participation vary by type of secondary level qualification? England and Germany in comparison. Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 2019, 38(6), 615–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Halloran, P. Gender differences in formal on-the-job training: Incidence, duration, and intensity. Labour 2008, 22(4), 629–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaud, S.; Lakhdari, M.; Morin, L. The determinants of participation in non-mandatory training. Relations Ind. 2004, 59(4), 724–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, S.; Weiss, F.; Hubert, T. Explaining the class gap in training: The role of employment relations and job characteristics. Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 2011, 30(2), 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, P.; Birdi, K. Employee age and voluntary development activity. Int. J. Train. Dev. 1998, 2(3), 190–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Lin, Z. Participation in workplace employer-sponsored training in Canada: Role of firm characteristics and worker attributes. Contemp. Econ. Policy 2011, 29(3), 416–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, R.; Gomes, M. Do Governo Eletrónico à Governança Digital: Modelos e Estratégias de Governo Transformacional. Ciências e Políticas Públicas / Public Sci. Policies 2021, 7(1), 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ţicu, D. New tendencies in public administration: from the new public management (NPM) and new governance (NG) to e-government. MATEC Web Conf. 2021, 342, 08002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, F.; Almeida, W.; Varajão, J. Digital transformation success in the public sector: A systematic literature review of cases, processes, and success factors. Inf. Polity 2022, 1, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, A.; Weerakkody, V.; Daowd, A. Studying Transformational Government: A review of the existing methodological approaches and future outlook. Gov. Inf. Q. 2020, 37(2), 101458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. The OECD Digital Government Policy Framework: Six dimensions of a Digital Government 02. 2020. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1787/f64fed2a-en (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- European Commission. Índice de Digitalidade da Economia e da Sociedade (IDES) de 2021 - Portugal. 2022. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/countries-digitisation-performance (accessed on 31/01/2023).

- Vuorikari, R.; Kluzer, S.; Punie, Y. DigComp 2.2. The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens. With new examples of knowledge, skills and attitudes. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberländer, M.; Beinicke, A.; Bipp, T. Digital competencies: A review of the literature and applications in the workplace. Comput. Educ. 2020, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.; Teixeira, P. Productivity, wages, and the returns to firm-provided training: fair shared capitalism. Int. J. Manpow. 2013, 34(7), 776–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgellis, Y.; Lange, T. Participation in continuous, on-the-job training and the impact on job satisfaction: Longitudinal evidence from the German labour market. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 18(6), 969–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.; Urwin, P. Age and Participation in Vocational Education and Training. Work. Employ. Soc. A J. Br. Sociol. Assoc. 2001, 15(4), 763–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farto, J. A Formação na Administração Pública: Preparação para a Transformação Digital. Tese de Mestrado; Polytechnic Institute of Leiria: Leiria, 10-11-2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lazear, E. Firm-specific human capital: a skill-weights approach. J. Polit. Econ. 2009, 117(5), 914–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falck, O.; Lindlacher, V.; Wiederhold, S. Elderly Left Behind? How Older Workers Can Participate in the Modern Labor Market. CESifo Forum. 2022, 23(5), 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, P.; Latreille, P.; Jones, M.; Blackaby, D. Is there a public sector training advantage? Evidence from the workplace employment relations survey. Br. J. Ind. Relations 2008, 46(4), 674–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, J.; Black, D.; Loewenstein, M. Gender Differences in Training, Capital, and Wages. J. Hum. Resour. 1993, 28(2), 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzenberger, B.; Muehler, G. Dips and floors in workplace training: Gender differences and supervisors. Scott. J. Polit. Econ. 2015, 62(4), 400–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truitt, D. Effect of training and development on employee attitude as it relates to training and work proficiency. SAGE Open 2011, 1(3), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research methods for business students, Eight Ed. ed; Pearson Education: New York, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).