Submitted:

13 June 2023

Posted:

14 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature review

2.1. Communication on sustainable development

2.2. Sustainable development goals

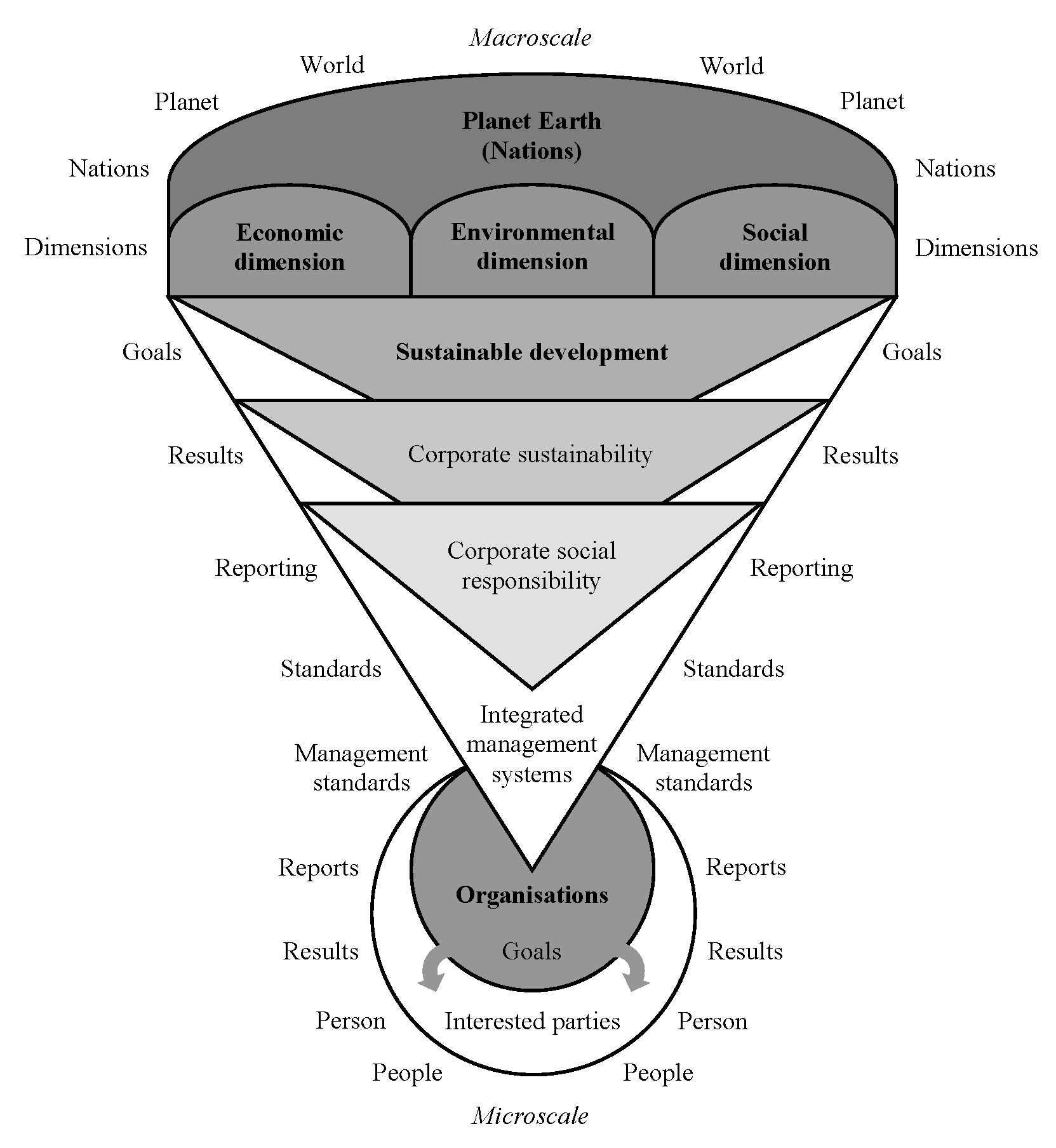

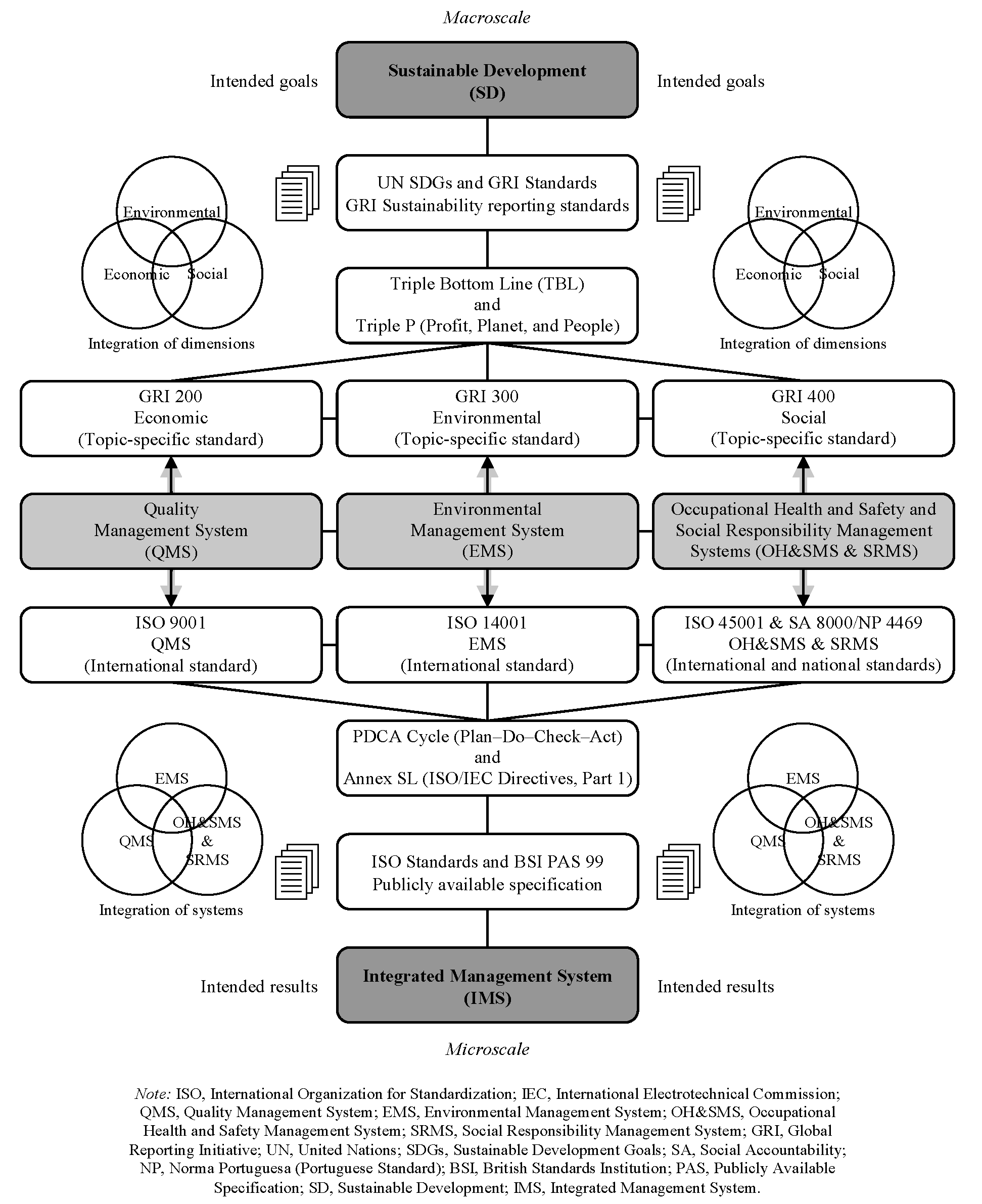

2.3. Sustainable development through management systems: a proposed framework

2.4. Communication through management systems & institutional reports

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research sample

- Made an institutional website accessible on the Internet on July 31, 2019 (i.e., the final date of the exploratory analysis).

- Disclosed at least one of their institutional reports on the website in the past four years (i.e., published from 2015 to 2018).

3.2. Research method

3.3. Research data

4. Results

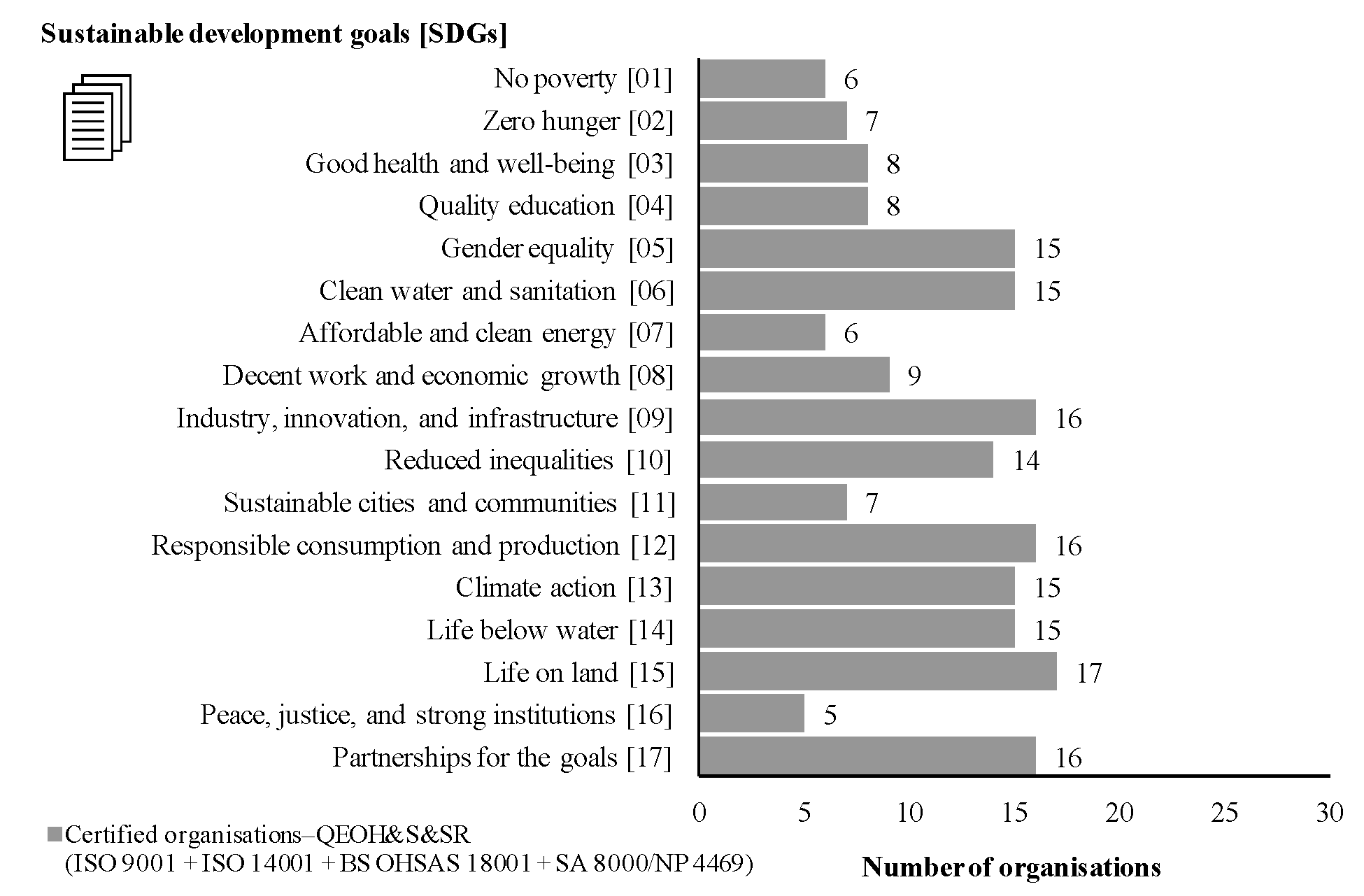

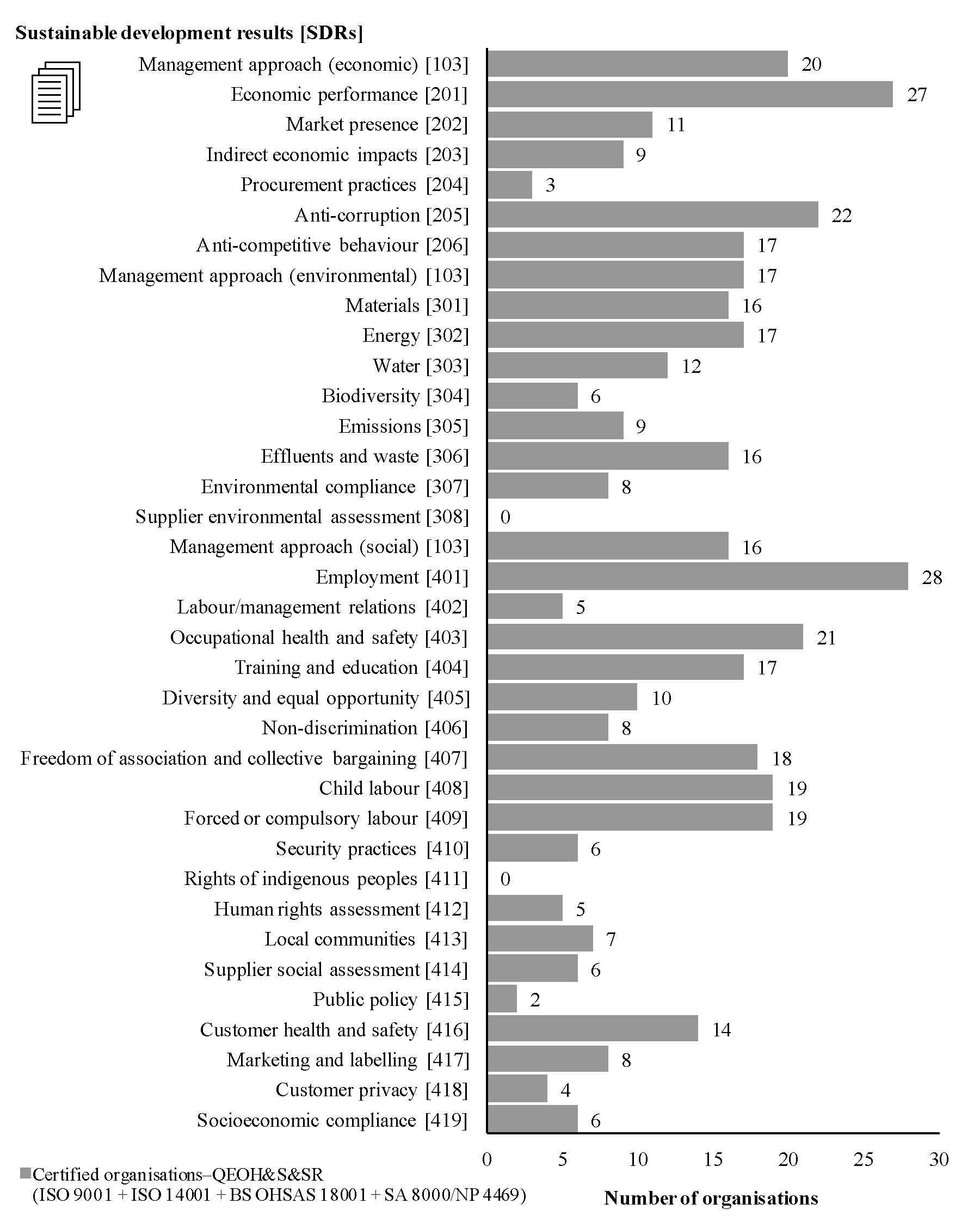

4.1. Descriptive statistics analysis

4.2. Bivariate correlation analysis

5. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meadows, D. H., Meadows, D. L., Randers, J., & Behrens III, W. W. (1972). The limits to growth: A report for the club of Rome’s project on the predicament of mankind. Universe Books.

- World Commission on Environment and Development. (1987a). Our common future. Oxford University Press.

- World Commission on Environment and Development. (1987b). The report of the world commission on environment and development: Our common future (UN General Assembly No. A/42/427). United Nations (UN). http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/42/427&Lang=E.

- Cöster, M., Dahlin, G., & Isaksson, R. (2020). Are they reporting the right thing and are they doing it right?—A measurement maturity grid for evaluation of sustainability reports. Sustainability, 12(24), Article 10393. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410393. [CrossRef]

- Isaksson, R. (2021). Excellence for sustainability – Maintaining the license to operate. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 32(5-6), 489–500. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2019.1593044. [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P. (2005). Evolving sustainably: A longitudinal study of corporate sustainable development. Strategic Management Journal, 26(3), 197–218. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.441. [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. (2008). Envisioning sustainability three-dimensionally. Journal of Cleaner Production, 16(17), 1838–1846. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2008.02.008. [CrossRef]

- Strezov, V., Evans, A., & Evans, T. J. (2017). Assessment of the economic, social and environmental dimensions of the indicators for sustainable development. Sustainable Development, 25(3), 242–253. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.1649. [CrossRef]

- Rosati, F., & Faria, L. G. D. (2019). Addressing the SDGs in sustainability reports: The relationship with institutional factors. Journal of Cleaner Production, 215, 1312–1326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.12.107. [CrossRef]

- Steurer, R., Langer, M. E., Konrad, A., & Martinuzzi, A. (2005). Corporations, stakeholders and sustainable development I: A theoretical exploration of business–society relations. Journal of Business Ethics, 61(3), 263–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-005-7054-0. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F., Santos, G., & Gonçalves, J. (2018). The disclosure of information on sustainable development on the corporate website of the certified Portuguese organizations. International Journal for Quality Research, 12(1), 253–276. https://doi.org/10.18421/IJQR12.01-14. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, L., Silva, V., Sá, J. C., Lima, V., Santos, G., & Silva, R. (2022). B Corp versus ISO 9001 and 14001 certifications: Aligned, or alternative paths, towards sustainable development?. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 29(3), 496–508. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2214. [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. E., Phillips, R., & Sisodia, R. (2020). Tensions in stakeholder theory. Business & Society, 59(2), 213-231. [CrossRef]

- Siltaloppi, J., Rajala, R., & Hietala, H. (2021). Integrating CSR with business strategy: a tension management perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 174(3), 507-527. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, L., Ramos, A., Rosa, A., Braga, A.C. and Sampaio, P. (2016). Stakeholders satisfaction and sustainable success, Int. J. Ind. Syst. Eng., vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 144–157, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Welford, R. & Frost, S. (2006). Corporate Social Responsibility in Asian Supply Chains. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management.13, 166–176 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.121. [CrossRef]

- hou, Yinyoung, Manisha Singal, e Yoon Koh. 2016. “CSR and Financial Performance: The Role of CSR Awareness in the Restaurant Industry”. International Journal of Hospitality Management 57: 30–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.05.007P. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F., Santos, G., & Gonçalves, J. (2020). Critical analysis of information about integrated management systems and environmental policy on the Portuguese firms’ website, towards sustainable development. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(2), 1069–1088. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1866. [CrossRef]

- Tsalis, T. A., Malamateniou, K. E., Koulouriotis, D., & Nikolaou, I. E. (2020). New challenges for corporate sustainability reporting: United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for sustainable development and the sustainable development goals. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(4), 1617–1629. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1910. [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Pitman Publishing.

- Ikram, M., Zhang, Q., Sroufe, R., & Ferasso, M. (2021). Contribution of certification bodies and sustainability standards to sustainable development goals: An integrated grey systems approach. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 28, 326–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2021.05.019. [CrossRef]

- Van Marrewijk, M. (2003). Concepts and definitions of CSR and corporate sustainability: Between agency and communion. Journal of Business Ethics, 44(2-3), 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023331212247. [CrossRef]

- Robert, K. W., Parris, T. M., & Leiserowitz, A. A. (2005). What is sustainable development? Goals, indicators, values, and practice. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 47(3), 8–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/00139157.2005.10524444. [CrossRef]

- Pojasek, R. B. (2003). Scoring sustainability results. Environmental Quality Management, 13(1), 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1002/tqem.10100. [CrossRef]

- Azapagic, A. (2003). Systems approach to corporate sustainability: A general management framework. Process Safety and Environmental Protection, 81(5), 303–316. https://doi.org/10.1205/095758203770224342. [CrossRef]

- Siew, R. Y. J. (2015). A review of corporate sustainability reporting tools (SRTs). Journal of Environmental Management, 164, 180–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.09.010. [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, S., Del Baldo, M., Caputo, F., & Venturelli, A. (2022). Voluntary disclosure of sustainable development goals in mandatory non- financial reports: The moderating role of cultural dimension. Journal of International Financial Management & Accounting, 33(1), 83–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/jifm.12139. [CrossRef]

- PricewaterhouseCoopers International. (2019). SDG Challenge 2019: Creating a strategy for a better world (PwC Report No. SDG Challenge 2019). https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/services/sustainability/sustainable-development-goals/sdg-challenge-2019.html.

- Manes-Rossi, F., & Nicolo', G. (2022). Exploring sustainable development goals reporting practices:From symbolic to substantive approaches—Evidence from theenergy sector. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management,29(5), 1799–1815.https://doi.org/10.1002/csr. [CrossRef]

- Silva, S. (2021). Corporate contributions to the sustainable development goals: An empirical analysis informed by legitimacy theory. Journal of Cleaner Production, 292, Article 125962. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.125962. [CrossRef]

- Crane, A., & Ruebottom, T. (2011). Stakeholder theory and social identity: Rethinking stakeholder identification. Journal of Business Ethics, 102(S1), 77–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-1191-4. [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17b(1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108. [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. B. (2001). Resource-based theories of competitive advantage: A ten-year retrospective on the resource-based view. Journal of Management, 27(6), 643–650. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630102700602. [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101. [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M. A. (2015). Valuing stakeholder engagement and sustainability reporting. Corporate Reputation Review, 18(3), 210–222. https://doi.org/10.1057/crr.2015.9. [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M. A. (2021). The market for socially responsible investing: a review of the developments. Social Responsibility Journal, 17(3), 412–428. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-06-2019-0194. [CrossRef]

- Hummel, K., & Szekely, M. (2022). Disclosure on the sustainable development goals – Evidence from Europe. Accounting in Europe, 19(1), 152–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449480.2021.1894347. [CrossRef]

- Ionașcu, E., Mironiuc, M., Anghel, I., & Huian, M. C. (2020). The involvement of real estate companies in sustainable development—An analysis from the SDGs reporting perspective. Sustainability, 12(3), Article 798. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030798. [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W., Vidal, D. G., Chen, C., Petrova, M., Dinis, M. A. P., Yang, P., Rogers, S., Álvarez-Castañón, L. d. C., Djekic, I., Sharifi, A., & Neiva, S. (2022). An assessment of requirements in investments, new technologies and infrastructures to achieve the SDGs. Environmental Sciences Europe, 34, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-022-00629-9. [CrossRef]

- Lim, W. M., Chin, M. W. C., Ee, Y. S., Fung, C. Y., Giang, C. S., Heng, K. S., Kong, M. L. F., Lim, A. S. S., Lim, B. C. Y., Lim, R. T. H., Lim, T. Y., Ling, C. C., Mandrinos, S., Nwobodo, S., Phang, C. S. C., She, L., Sim, C. H., Su, S. I., Wee, G. W. E., & Weissmann, M. A. (2022). What is at stake in a war? A prospective evaluation of the Ukraine and Russia conflict for business and society. Global Business and Organizational Excellence, 23-36. https://doi.org/10.1002/joe.22162. [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R., & Barreiro-Gen, M. (2022). Organisations' contributions to sustainability. An analysis of impacts on the Sustainable Development Goals. Business Strategy and the Environment, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3305. [CrossRef]

- Welford, R. (Ed.). (1997). Hijacking Environmentalism: Corporate Responses to Sustainable Development (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315070889. [CrossRef]

- Büthe, T., & Mattli, W. (2011). The New Global Rulers: The Privatization of Regulation in the World Economy. Princeton University Press.

- Nunhes, T. V., Espuny, M., Lau áReis Campos, T., Santos, G., Bernardo, M., & Oliveira, O. J.(2022). Guidelines to build the bridge between sustainability and integrated management systems: A way to increase stakeholder engagement toward sustainable development. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management,29(5), 1617–1635.https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2308. [CrossRef]

- Rebelo, M. F., Santos, G., & Silva, R. (2016). Integration of management systems: Towards a sustained success and development of organizations. Journal of Cleaner Production, 127, 96–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.04.011. [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization & International Electrotechnical Commission. (2021). ISO/IEC Directives, Part 1: Consolidated ISO Supplement—Procedures for the technical work—Procedures specific to ISO (ISO/IEC Standard No. ISO/IEC Directives, Part 1). https://www.iso.org/sites/directives/current/consolidated/index.xhtml.

- Blind, K, & Heß, P. (2023).Stakeholder perceptions of the role of standards for addressing the sustainable development goals, Sustainable Production and Consumption, 37, 2023, 180-190, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2023.02.016. [CrossRef]

- British Standards Institution. (2012). Specification of common management system requirements as a framework for integration (BSI Standard No. PAS 99:2012). https://shop.bsigroup.com/ProductDetail?pid=000000000030254209.

- Instituto Português da Qualidade. (2019). Sistema de gestão da responsabilidade social—Requisitos e linhas de orientação para a sua utilização [Social responsibility management system—Requirements and guidelines for its usage] (IPQ Standard No. NP 4469:2019). https://lojanormas.ipq.pt/product/np-4469-2019/.

- International Organization for Standardization. (2015a). Environmental management systems—Requirements with guidance for use (ISO Standard No. ISO 14001:2015). https://www.iso.org/standard/60857.html.

- International Organization for Standardization. (2015b). Quality management systems—Requirements (ISO Standard No. ISO 9001:2015). https://www.iso.org/standard/62085.html.

- International Organization for Standardization. (2018b). Occupational health and safety management systems—Requirements with guidance for use (ISO Standard No. ISO 45001:2018). https://www.iso.org/standard/63787.html.

- International Organization for Standardization. (2015c). Quality management systems—Fundamentals and vocabulary (ISO Standard No. ISO 9000:2015). https://www.iso.org/standard/45481.html.

- British Standards Institution. (2007). Occupational health and safety management systems—Requirements (BSI Standard No. BS OHSAS 18001:2007). https://shop.bsigroup.com/ProductDetail/?pid=000000000030148086.

- International Organization for Standardization. (2010). Guidance on social responsibility (ISO Standard No. ISO 26000:2010). https://www.iso.org/standard/42546.html.

- Fonseca, L.M., Domingues, J.P., Machado, P.B. and Calderón, M. (2017). Management System Certification Benefits: Where Do We Stand? Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management (JIEM), 10(3), pp. 476-494; DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3926/jiem.2350. [CrossRef]

- Ikram, M., Zhang, Q., & Sroufe, R. (2020a). Developing integrated management systems using an AHP-Fuzzy VIKOR approach. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(6), 2265–2283. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2501. [CrossRef]

- Santos, G., Mendes, F., & Barbosa, J. (2011). Certification and integration of management systems: The experience of Portuguese small and medium enterprises. Journal of Cleaner Production, 19(17-18), 1965–1974. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2011.06.017. [CrossRef]

- Silva, C., Magano, J., Moskalenko, A., Nogueira, T., Dinis, M. A. P., & Sousa, H. F. P. (2020). Sustainable management systems standards (SMSS): Structures, roles, and practices in corporate sustainability. Sustainability, 12(15), Article 5892. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12155892. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Vivanco, A., Domingues, P., Sampaio, P., Bernardo, M., & Cruz-Cázares, C. (2019). Do multiple certifications leverage firm performance? A dynamic approach. International Journal of Production Economics, 218, 386–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2019.07.016. [CrossRef]

- Ikram, M., Zhang, Q., Sroufe, R., & Ferasso, M. (2020b). The social dimensions of corporate sustainability: An integrative framework including COVID-19 insights. Sustainability, 12(20), Article 8747. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208747. [CrossRef]

- Freundlieb, M., & Teuteberg, F. (2013). Corporate social responsibility reporting – A transnational analysis of online corporate social responsibility reports by market-listed companies: Contents and their evolution. International Journal of Innovation and Sustainable Development, 7 (1), 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Sarachaga, J. M. (2021). Shortcomings in reporting contributions towards the sustainable development goals. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 28(4), 1299–1312. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2129. [CrossRef]

- Erin, O. A., & Bamigboye, O. A. (2022). Evaluation and analysis of SDG reporting: evidence from Africa. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 18(3), 369–396. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAOC-02-2020-0025. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, L., & Carvalho, F. (2019). The reporting of SDGs by quality, environmental, and occupational health and safety-certified organizations. Sustainability, 11(20), Article 5797. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205797. [CrossRef]

- Izzo, M. F., Ciaburri, M., & Tiscini, R. (2020). The challenge of sustainable development goal reporting: The first evidence from Italian listed companies. Sustainability, 12(8), Article 3494. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083494. [CrossRef]

- Guarini, E., Mori, E., & Zuffada, E. (2022). Localizing the sustainable development goals: A managerial perspective. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, 34(5), 583–601.

- Leal, W., Azeiteiro, U., Alves, F., Pace, P., Mifsud, M., Brandli, L., et al. (2018). Reinvigorating the sustainable development research agenda: The role of the sustainable development goals (SDG). International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 25(2), 131–142. [CrossRef]

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development (UN General Assembly Resolution No. A/RES/70/1). https://undocs.org/A/RES/70/1.

- Fonseca, L. M., Domingues, J. P., & Dima, A. M. (2020). Mapping the sustainable development goals relationships. Sustainability, 12(8), Article 3359. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083359. [CrossRef]

- Heemskerk, B., Pistorio, P., & Scicluna, M. (2002). Sustainable development reporting: Striking the balance. World Business Council for Sustainable Development. https://www.wbcsd.org/Programs/Redefining-Value/External-Disclosure/Reporting-matters/Resources/Sustainable-Development-Reporting-Striking-the-balance.

- Carvalho, F., Domingues, P., & Sampaio, P. (2019). Communication of commitment towards sustainable development of certified Portuguese organisations: Quality, environment and occupational health and safety. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 36(4), 458–484. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQRM-04-2018-0099. [CrossRef]

- Saber, M., & Weber, A. (2019). Sustainable grocery retailing: Myth or reality?—A content analysis. Business and Society Review, 124(4), 479–496. https://doi.org/10.1111/basr.12187. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, E. H., Rambaree, B. B., & Macassa, G. (2021). CSR reporting of stakeholders’ health: Proposal for a new perspective. Sustainability, 13(3), Article 1133. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031133. [CrossRef]

- Girella, L., Zambon, S., & Rossi, P. (2019). Reporting on sustainable development: A comparison of three Italian small and medium-sized enterprises. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 26(4), 981–996. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1738. [CrossRef]

- Global Reporting Initiative. (2020). Consolidated set of GRI sustainability reporting standards 2020 (GRI Standards No. GRI 2020). https://www.globalreporting.org/standards/gri-standards-download-center/.

- SDG Compass. (2020). The guide for business action on the SDGs. Retrieved from https://sdgcompass.org.

- Tsalis, T. A., Malamateniou, K. E., Koulouriotis, D., & Nikolaou, I. E. (2020). New challenges for corporate sustainability reporting: United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for sustainable development and the sustainable development goals. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(4), 1617–1629. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1910. [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. (1997). Cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st century business. Capstone Publishing Limited.

- Elkington, J. (2004). Enter the triple bottom line. In A. Henriques & J. Richardson (Eds.), The triple bottom line: Does it all add up? (pp. 1–16). Earthscan.

- Pacheco, J. A. B., Teijeiro-Álvarez, M. M., & García-Álvarez, M. T. (2020). Sustainable development in the economic, environmental, and social fields of Ecuadorian universities. Sustainability, 12(18), Article 7384. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187384. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X., Castka, P., & Searcy, C. (2020). ISO standards: A platform for achieving sustainable development goal 2. Sustainability, 12(2), Article 9332. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229332. [CrossRef]

- Rashed, A. H., Rashdan, S. A., & Ali-Mohamed, A. Y. (2022). Towards effective environmental sustainability reporting in the large industrial sector of Bahrain. Sustainability, 14(1), Article 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010219. [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, A., Costa, R., Gastaldi, M., Ghiron, N. L., & Montalvan, R. A. V. (2021). Implications for sustainable development goals: A framework to assess company disclosure in sustainability reporting. Journal of Cleaner Production, 319, Article 128624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128624. [CrossRef]

- Elalfy, A., Weber, O., & Geobey, S. (2021). The sustainable development goals (SDGs): A rising tide lifts all boats? Global reporting implications in a post SDGs world. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 22(3), 557–575. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAAR-06-2020-0116. [CrossRef]

- Ivic, A., Saviolidis, N. M., & Johannsdottir, L. (2021). Drivers of sustainability practices and contributions to sustainable development evident in sustainability reports of European mining companies. Discover Sustainability, 2(17), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-021-00025-y. [CrossRef]

- Siva, V., Gremyr, I., Bergquist, B., Garvare, R., Zobel, T., & Isaksson, R. (2016). The support of quality management to sustainable development: A literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 138, 148–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.01.020. [CrossRef]

- Alsawafi, A., Lemke, F., & Yang, Y. (2021). The impacts of internal quality management relations on the triple bottom line: A dynamic capability perspective. International Journal of Production Economics, 232, Article 107927. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2020.107927. [CrossRef]

- Chavez, R., Yu, W., Jajja, M. S. S., Lecuna, A., & Fynes, B. (2020). Can entrepreneurial orientation improve sustainable development through leveraging internal lean practices?. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(6), 2211–2225. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2496. [CrossRef]

- Tarí, J. J., Molina-Azorín, J. F., López-Gamero, M. D., & Pereira-Moliner, J. (2021). The association between environmental sustainable development and internalization of a quality standard. Business Strategy and the Environment, 30(5), 2587–2599. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2765. [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M. A. (2018). Theoretical insights on integrated reporting: The inclusion of non-financial capitals in corporate disclosures. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 23(4), 567–581. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCIJ-01-2018-0016. [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M. A. (2021). The market for socially responsible investing: a review of the developments. Social Responsibility Journal, 17(3), 412–428. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-06-2019-0194. [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M. A. (2022). The rationale for ISO 14001 certification: A systematic review and a cost–benefit analysis. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 29(4), 1067–1083. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2254. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, L. M. C. M. (2015). ISO 14001:2015: An improved tool for sustainability. Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management, 8(1), 37–50. http://dx.doi.org/10.3926/jiem.1298. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q. (2004). Sustainable development of occupational health and safety management system − Active upgrading of corporate safety culture. International Journal on Architectural Science, 5(4), 108–113. http://www.bse.polyu.edu.hk/researchCentre/Fire_Engineering/summary_of_output/journal/IJAS/V5/p.108-113.pdf.

- Jilcha, K., & Kitaw, D. (2017). Industrial occupational safety and health innovation for sustainable development. Engineering Science and Technology, an International Journal, 20(1), 372–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jestch.2016.10.011. [CrossRef]

- Marhavilas, P., Koulouriotis, D., Nikolaou, I., & Tsotoulidou, S. (2018). International occupational health and safety management-systems standards as a frame for the sustainability: Mapping the territory. Sustainability, 10(10), Article 3663. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103663. [CrossRef]

- 98. Social Accountability International. (2014). Social accountability 8000 (SAI Standard No. SA 8000:2014). https://sa-intl.org/resources/sa8000-standard/.

- Murmura, F., & Bravi, L. (2020). Developing a corporate social responsibility strategy in India using the SA 8000 standard. Sustainability, 12(8), Article 3481. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083481. [CrossRef]

- Santos, G., Murmura, F., & Bravi, L. (2018). SA 8000 as a tool for a sustainable development strategy. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 25(1), 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1442. [CrossRef]

- Jonkutė, G., Staniškis, J. K., & Dukauskaitė, D. (2011). Social responsibility as a tool to achieve sustainable development in SMEs. Environmental Research, Engineering and Management, 57(3), 67–81. https://erem.ktu.lt/index.php/erem/article/view/465.

- Castka, P., Bamber, C. J., Bamber, D. J., & Sharp, J. M. (2004). Integrating corporate social responsibility (CSR) into ISO management systems – In search of a feasible CSR management system framework. The TQM Magazine, 16(3), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1108/09544780410532954. [CrossRef]

- Oskarsson, K., & Von Malmborg, F. (2005). Integrated management systems as a corporate response to sustainable development. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 12(3), 121–128. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.78. [CrossRef]

- Nadae, J., Carvalho, M. M., & Vieira, D. R. (2021). Integrated management systems as a driver of sustainability performance: Exploring evidence from multiple-case studies. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 38(3), 800–821. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQRM-12-2019-0386. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, A. S., Silva, L. B., Souza, V. F., & Morioka, S. N. (2022). Integrated management systems: Their organizational impacts. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 33(7-8), 794–817. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2021.1893685. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F. J. F. (2019). A comunicação de resultados sobre desenvolvimento sustentável nas organizações portuguesas certificadas em qualidade, ambiente e segurança [The communication of results on sustainable development in the certified Portuguese organisations in quality, environment, and safety] [Master’s thesis, Instituto Superior de Engenharia do Porto – Instituto Politécnico do Porto]. Repositório Científico do Instituto Politécnico do Porto. http://hdl.handle.net/10400.22/14980.

- Derqui, B. (2020). Towards sustainable development: Evolution of corporate sustainability in multinational firms. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(6), 2712–2723. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1995. [CrossRef]

- Gerged, A. M., Cowton, C. J., & Beddewela, E. S. (2018). Towards sustainable development in the Arab Middle East and North Africa region: A longitudinal analysis of environmental disclosure in corporate annual reports. Business Strategy and the Environment, 27(4), 572–587. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2021. [CrossRef]

- De Iorio, S., Zampone, G., & Piccolo, A. (2022). Determinant factors of SDG disclosure in the university context. Administrative Sciences, 12(1), Article 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12010021. [CrossRef]

- Gunawan, J., Permatasari, P., & Tilt, C. (2020). Sustainable development goal disclosures: Do they support responsible consumption and production?. Journal of Cleaner Production, 246, Article 118989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118989. [CrossRef]

- Abbott, W. F., & Monsen, R. J. (1979). On the measurement of corporate social responsibility: Self-reported disclosures as a method of measuring corporate social involvement. Academy of Management Journal, 22(3), 501–515. https://doi.org/10.5465/255740. [CrossRef]

- Schober, P., Boer, C., & Schwarte, L. A. (2018). Correlation coefficients: Appropriate use and interpretation. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 126(5), 1763–1768. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000002864. [CrossRef]

- Ching, H. Y., & Gerab, F. (2017). Sustainability reports in Brazil through the lens of signaling, legitimacy and stakeholder theories. Social Responsibility Journal, 13(1), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-10-2015-0147. [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. (2018). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Heras-Saizarbitoria, I., Urbieta, L., & Boiral, O. (2022). Organizations’ engagement with sustainable development goals: From cherry-picking to SDG-washing?. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 29(2), 316–328. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2202. [CrossRef]

- Bastas, A., & Liyanage, K. (2018). ISO 9001 and supply chain integration principles based sustainable development: A delphi study. Sustainability, 10(12), Article 4569. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124569. [CrossRef]

- Lambrechts, W., Son-Turan, S., Reis, L., & Semeijn, J. (2019). Lean, green and clean? Sustainability reporting in the logistics sector. Logistics, 3(1), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics3010003. [CrossRef]

- Kolsi, M. C., Ananzeh, M., & Awawdeh, A. (2021). Compliance with the global reporting initiative standards in Jordan: Case study of hikma pharmaceuticals. International Journal of Sustainable Engineering, 14(6), 1572–1586. https://doi.org/10.1080/19397038.2021.1970273. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, L. (2022). The EFQM 2020 model. A theoretical and critical review. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 33:9-10, 1011-1038, DOI: 10.1080/14783363.2021.1915121. [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization. (2018a). Contributing to the UN sustainable development goals with ISO standards. https://www.iso.org/publication/PUB100429.html.

- United Nations Economic and Social Council - ECOSOC. (2022). Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals. Report of the Secretary-General (No 9780191577468; April.

- Leal Filho W, Viera Trevisan Laí, Simon Rampasso I, Anholon R, Pimenta Dinis MA, Londero Brandli L, Sierra J, Lange Salvia A, Pretorius R, Nicolau M, Paulino Pires Eustachio João Henrique, Mazutti J. (2023). When the alarm bells ring: Why the UN sustainable development goals may not be achieved by 2030. Journal of Cleaner Production. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.137108. [CrossRef]

| Discipline | Definition of the term or concept | Reference(s) |

| Quality | Degree to which a set of inherent characteristics of an object fulfils requirements. | ISO [53] |

| Environment | Surroundings in which an organisation operates, including air, water, land, natural resources, flora, fauna, humans, and their interrelationships. | ISO [50] |

| Occupational health and safety (OH&S) | Conditions and factors that affect, or could affect, the health and safety of employees or other workers (including temporary workers and contractor personnel), visitors, or any other person in the workplace. | BSI [54] |

| Social responsibility | Responsibility of an organisation for the impacts of its decisions and activities on society and the environment, through transparent and ethical behaviour that contributes to sustainable development, including health and the welfare of society; considers the expectations of stakeholders; is in compliance with applicable law and consistent with international norms of behaviour; and is integrated throughout the organisation and practised in its relationships. | IPQ [49] and ISO [55] |

| Dimension | Potential issues | Main standard(s) |

| Economic | Economic performance and development Technology and innovation Value and supply chain Employment Business Poverty Income Others |

ISO 9001:2015 Quality management systems—Requirements |

| Environmental | Protection of biodiversity and natural habitats Pollution of land, water, or air Natural resource use Climate change Energy use Others |

ISO 14001:2015 Environmental management systems—Requirements with guidance for use |

| Social | Education, training, and literacy Community involvement Health and safety Labour relations Quality of life Social equity Culture Others |

ISO 45001:2018 Occupational health and safety management systems—Requirements with guidance for use ISO 26000:2010 Guidance on social responsibility SA 8000:2014 Social accountability NP 4469:2019 Social responsibility management system—Requirements and guidelines for its usage |

| Sustainable development goals (SDGs) | ISO 9001 (2015) |

ISO 14001 (2015) |

ISO 45001 (2018) |

ISO 26000 (2010) |

SA 8000 (2014) |

NP 4469 (2019) |

| SDG 01: No poverty | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| SDG 02: Zero hunger | ● | ● | ● | |||

| SDG 03: Good health and well-being | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| SDG 04: Quality education | ● | ● | ● | |||

| SDG 05: Gender equality | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| SDG 06: Clean water and sanitation | ● | ● | ● | |||

| SDG 07: Affordable and clean energy | ● | ● | ● | |||

| SDG 08: Decent work and economic growth | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| SDG 09: Industry, innovation, and infrastructure | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| SDG 10: Reduced inequalities | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| SDG 11: Sustainable cities and communities | ● | ● | ● | |||

| SDG 12: Responsible consumption and production | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| SDG 13: Climate action | ● | ● | ● | |||

| SDG 14: Life below water | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| SDG 15: Life on land | ● | ● | ● | |||

| SDG 16: Peace, justice, and strong institutions | ● | ● | ● | |||

| SDG 17: Partnerships for the goals | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● |

| Scope | Referential | Communication requirements | Internal | External |

| Quality management systems | ISO 9001:2015 | 5.2.2 Communicating the quality policy 7.4 Communication 8.2.1 Customer communication 8.4.3 Information for external providers |

● ● |

● ● ● ● |

| Environmental management systems | ISO 14001:2015 | 7.4 Communication 7.4.1 General 7.4.2 Internal communication 7.4.3 External communication |

● ● ● |

● ● ● |

| Occupational health and safety management systems | ISO 45001:2018 | 7.4 Communication 7.4.1 General 7.4.2 Internal communication 7.4.3 External communication |

● ● ● |

● ● ● |

| Social responsibility management systems | ISO 26000:2010 | 7.5 Communication on social responsibility 7.5.1 The role of communication in social responsibility 7.5.2 Characteristics of information relating to social responsibility 7.5.3 Types of communication on social responsibility 7.5.4 Stakeholder dialogue on communication about social responsibility |

● ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● |

| SA 8000:2014 | 9.5 Internal involvement and communication | ● | ||

| NP 4469:2019 | 7.4 Communication 7.4.1 General 7.4.2 Internal communication 7.4.3 External communication |

● ● ● |

● ● ● |

|

| Integrated management systems | PAS 99:2012 | 7.4 Communication | ● | ● |

| Certified management systems (standard) | n | % |

| QMS (ISO 9001) | 34 | 100 |

| EMS (ISO 14001) | 34 | 100 |

| OH&SMS (BS OHSAS 18001) | 34 | 100 |

| SRMS (SA 8000) | 23 | 67.6 |

| SRMS (NP 4469) | 11 | 32.4 |

| Correlation coefficient value | Correlation level interpretation |

| 0.00–0.10 | Negligible correlation |

| 0.10–0.39 | Weak correlation |

| 0.40–0.69 | Moderate correlation |

| 0.70–0.89 | Strong correlation |

| 0.90–1.00 | Very strong correlation |

| Institutional reports | n | % |

| Sustainability report | 22 | 64.7 |

| Social responsibility report | 4 | 11.8 |

| Environmental report | 4 | 11.8 |

| Occupational health and safety report | 0 | 0.0 |

| Management report | 6 | 17.6 |

| Accounts report | 23 | 67.6 |

| Accounts and management report | 1 | 2.9 |

| Financial report | 7 | 20.6 |

| Corporate governance report | 10 | 29.4 |

| Integrated report | 0 | 0.0 |

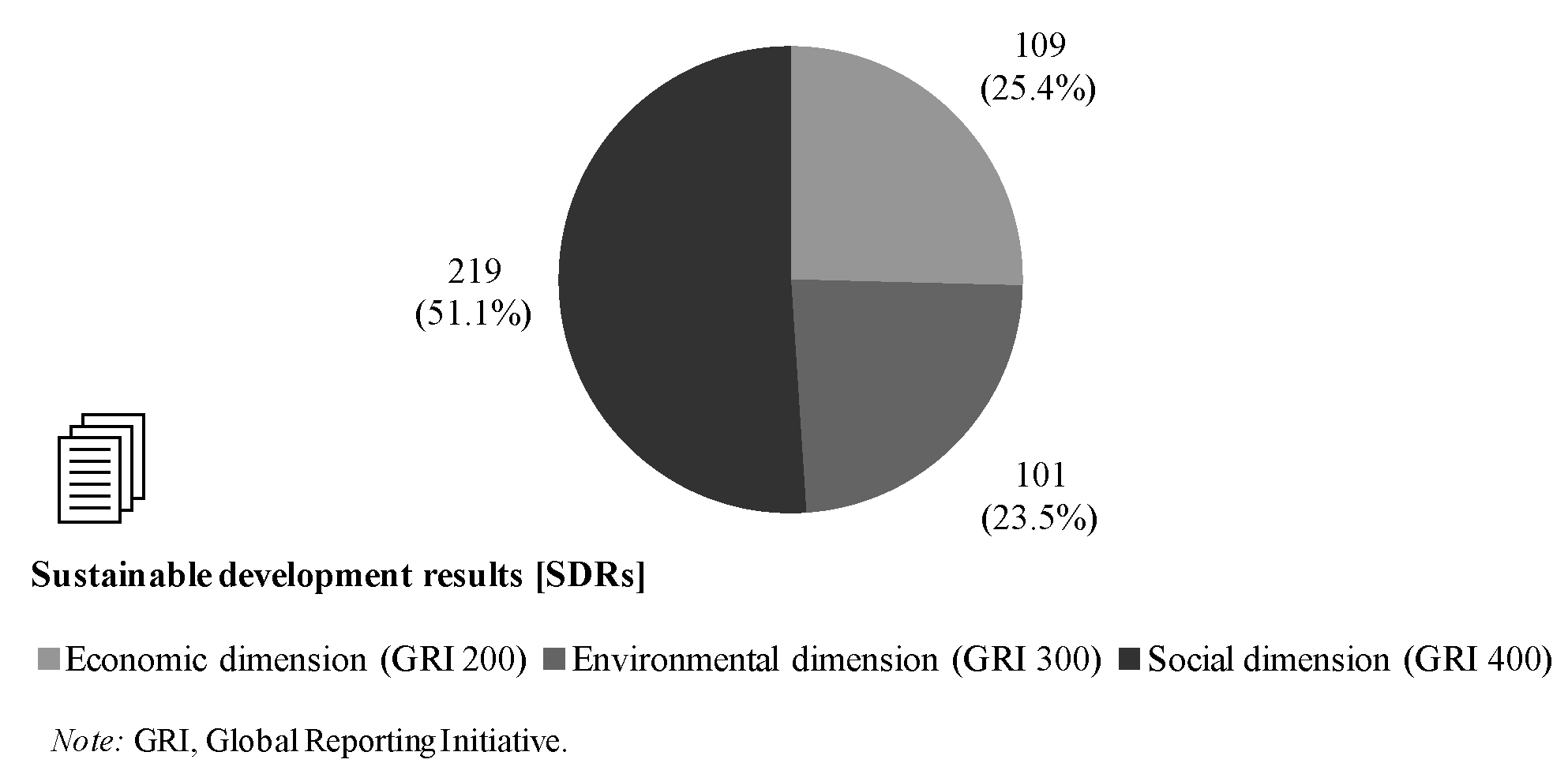

| Categories of analysis | Subcategories of analysis | n | % |

| Social | SDG 01: No poverty | 6 | 17.6 |

| Social | SDG 02: Zero hunger | 7 | 20.6 |

| Social | SDG 03: Good health and well-being | 8 | 23.5 |

| Social | SDG 04: Quality education | 8 | 23.5 |

| Economic and social | SDG 05: Gender equality | 15 | 44.1 |

| Environmental and social | SDG 06: Clean water and sanitation | 15 | 44.1 |

| Economic and environmental | SDG 07: Affordable and clean energy | 6 | 17.6 |

| Economic and social | SDG 08: Decent work and economic growth | 9 | 26.5 |

| Economic | SDG 09: Industry, innovation, and infrastructure | 16 | 47.1 |

| Economic and social | SDG 10: Reduced inequalities | 14 | 41.2 |

| Environmental and social | SDG 11: Sustainable cities and communities | 7 | 20.6 |

| Economic and social | SDG 12: Responsible consumption and production | 16 | 47.1 |

| Environmental | SDG 13: Climate action | 15 | 44.1 |

| Environmental | SDG 14: Life below water | 15 | 44.1 |

| Environmental | SDG 15: Life on land | 17 | 50.0 |

| Social | SDG 16: Peace, justice, and strong institutions | 5 | 14.7 |

| Economic, environmental, and social | SDG 17: Partnerships for the goals | 16 | 47.1 |

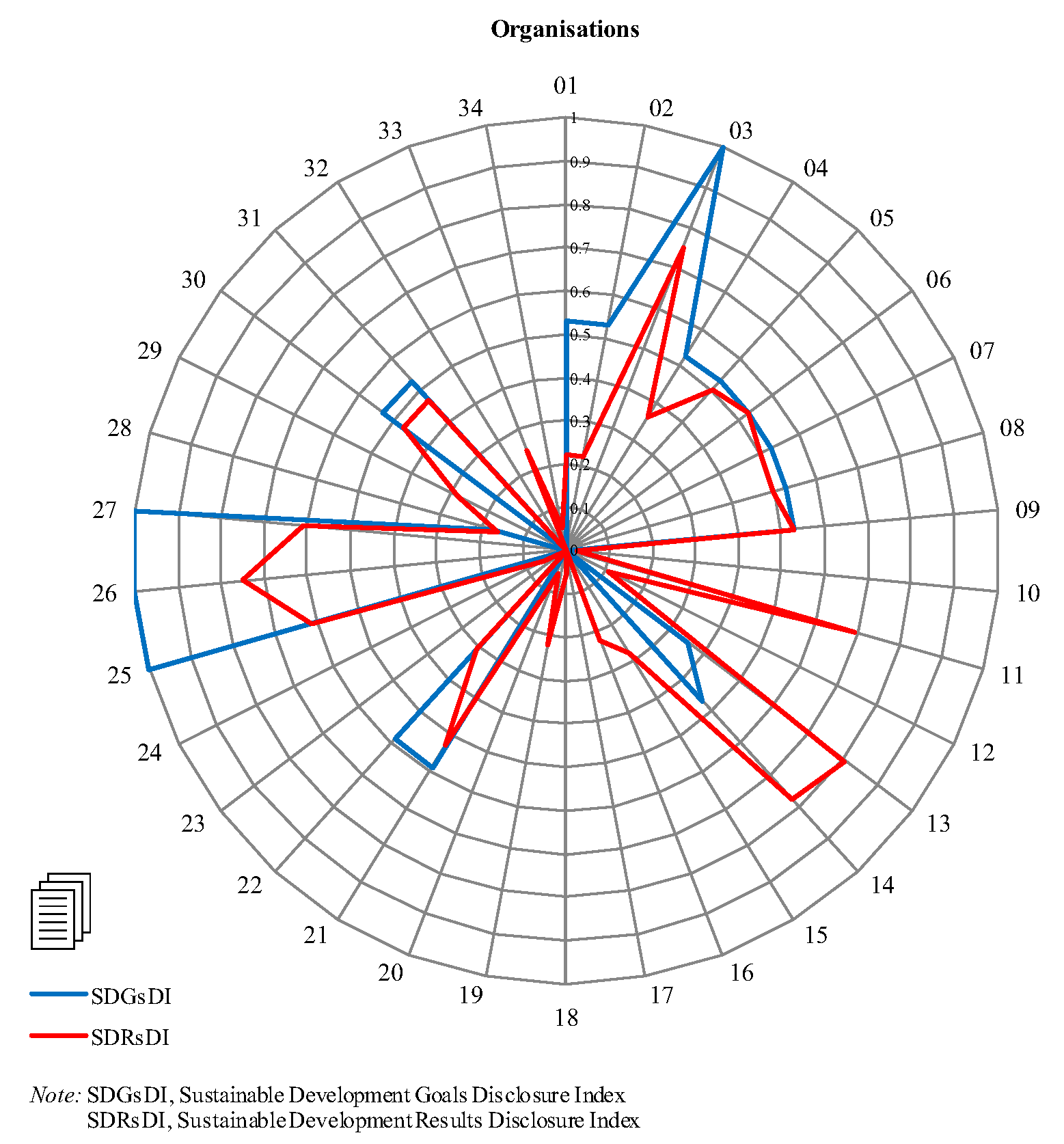

| j | Certification body | Economic activity | Business sector | District | SDGsDI | SDRsDI |

| 01 | APCER | TA | Public | Lisboa | 0.529 | 0.222 |

| 02 | APCER | TA | Public | Lisboa | 0.529 | 0.222 |

| 03 | APCER | OSA | Public | Lisboa | 1.000 | 0.750 |

| 04 | APCER | TA | Public | Lisboa | 0.529 | 0.361 |

| 05 | APCER | WCTS | Public | Setúbal | 0.529 | 0.500 |

| 06 | APCER | WCTS | Public | Faro | 0.529 | 0.528 |

| 07 | APCER | WCTS | Public | Coimbra | 0.529 | 0.500 |

| 08 | SGS ICS | WCTS | Public | Porto | 0.529 | 0.500 |

| 09 | SGS ICS | WCTS | Public | Vila Real | 0.529 | 0.528 |

| 10 | APCER | WRT | Private | Porto | 0.000 | 0.028 |

| 11 | APCER | E | Public | Lisboa | 0.000 | 0.694 |

| 12 | SGS ICS | C | Private | Lisboa | 0.000 | 0.111 |

| 13 | SGS ICS | WCTS | Public | Braga | 0.353 | 0.806 |

| 14 | BVC | AFSA | Private | Lisboa | 0.471 | 0.778 |

| 15 | APCER | SWM | Public | Faro | 0.000 | 0.278 |

| 16 | APCER | AFSA | Private | Lisboa | 0.000 | 0.222 |

| 17 | EIC | OSA | Private | Lisboa | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 18 | BVC | C | Private | Lisboa | 0.000 | 0.056 |

| 19 | APCER | AFSA | Private | Lisboa | 0.000 | 0.222 |

| 20 | APCER | MRPP | Private | Castelo Branco | 0.000 | 0.056 |

| 21 | APCER | SWM | Public | Porto | 0.588 | 0.528 |

| 22 | BVC | MFPBTP | Private | Portalegre | 0.588 | 0.306 |

| 23 | BVC | C | Private | Lisboa | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 24 | SGS ICS | MNMMP | Private | Aveiro | 0.000 | 0.056 |

| 25 | APCER | EPD | Private | Lisboa | 1.000 | 0.611 |

| 26 | APCER | OSA | Private | Lisboa | 1.000 | 0.750 |

| 27 | APCER | TS | Private | Lisboa | 1.000 | 0.611 |

| 28 | SGS ICS | OSA | Private | Lisboa | 0.176 | 0.167 |

| 29 | APCER | WCTS | Public | Setúbal | 0.000 | 0.278 |

| 30 | SGS ICS | SWM | Public | Porto | 0.529 | 0.472 |

| 31 | BVC | C | Private | Lisboa | 0.529 | 0.472 |

| 32 | APCER | TS | Private | Lisboa | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 33 | SGS ICS | SWM | Private | Portalegre | 0.000 | 0.250 |

| 34 | EIC | WRT | Private | Setúbal | 0.000 | 0.056 |

| Variable | N | Minimum | Maximum | Sum | Mean | SD | Variance |

| SDGsDI | 34 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 11.471 | 0.337 | 0.348 | 0.121 |

| SDRsDI | 34 | 0.000 | 0.806 | 11.917 | 0.350 | 0.256 | 0.065 |

| Correlation between SDGsDI and SDRsDI | ||||

| Correlation | Statistical test | N | Correlation coefficient |

p-value (two-tailed) |

| Pearson’s ‘r’ (r) | Parametric | 34 | 0.733 | 0.000** |

| Spearman’s ‘rho’ (ρ) | Non-parametric | 34 | 0.697 | 0.000** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).