1. Introduction

Hereditary hemochromatosis (HH) is the most common form of hereditary disorder of iron metabolism. It is caused by an autosomal recessive disorder occurring as a mutation of the HFE gene, which is found in the p-arm (short arm) of chromosome 6. The C282Y mutation is the most common mutation linked to hemochromatosis and occurs in 90% of diagnosed patients of northern European origin [

1]. The disorder is characterized by an increase in the absorption of iron due to the disordered expression of hepcidin, which is the main regulator of iron homeostasis. Its expression is controlled by the free HFE protein (not bound to transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1)), which sends signals for hepcidin expression. If the number of HFE proteins bound to TfR1 increases, the signal is interrupted and hepcidin expression decreases [

2]. Reduction of hepcidin expression leads to progressive, systematic accumulation of iron in organ cells and tissue, which finally results in their degeneration and the onset of organ dysfunction [

3]. Patients experiencing secondary iron overload are known to have changes in the retina, but these changes are due to the toxic action of deferoxamine mesylate, which, on account of its chelating characteristics, is used to eliminate excess iron. Researchers have shown that patients treated with deferoxamine have developed a number of disorders such as retinopathy, bull’s eye maculopathy, and vitelliform maculopathies [

4]. An important point to emphasize is that morphological changes in the retina are not only related to the toxic effect of deferoxamine mesylate but can also be a result of iron deposition in secondary hemochromatosis and pathophysiological processes in hereditary hemochromatosis that has not been treated with chelating agents [

5]. The importance of the HFE gene in regulating the homeostasis of retinal iron was described earlier, and the knockout mouse model has been used to show how iron accumulation may have destructive effects on the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), causing oxidative stress and damage [

6,

7]. The aim of this paper is to describe structural changes in the macula in two patients suffering from HH bonded to the C282Y mutation of the HFE gene, who were treated with erythrocytapheresis and phlebotomy and were not exposed to deferoxamine or any other drug chelation.

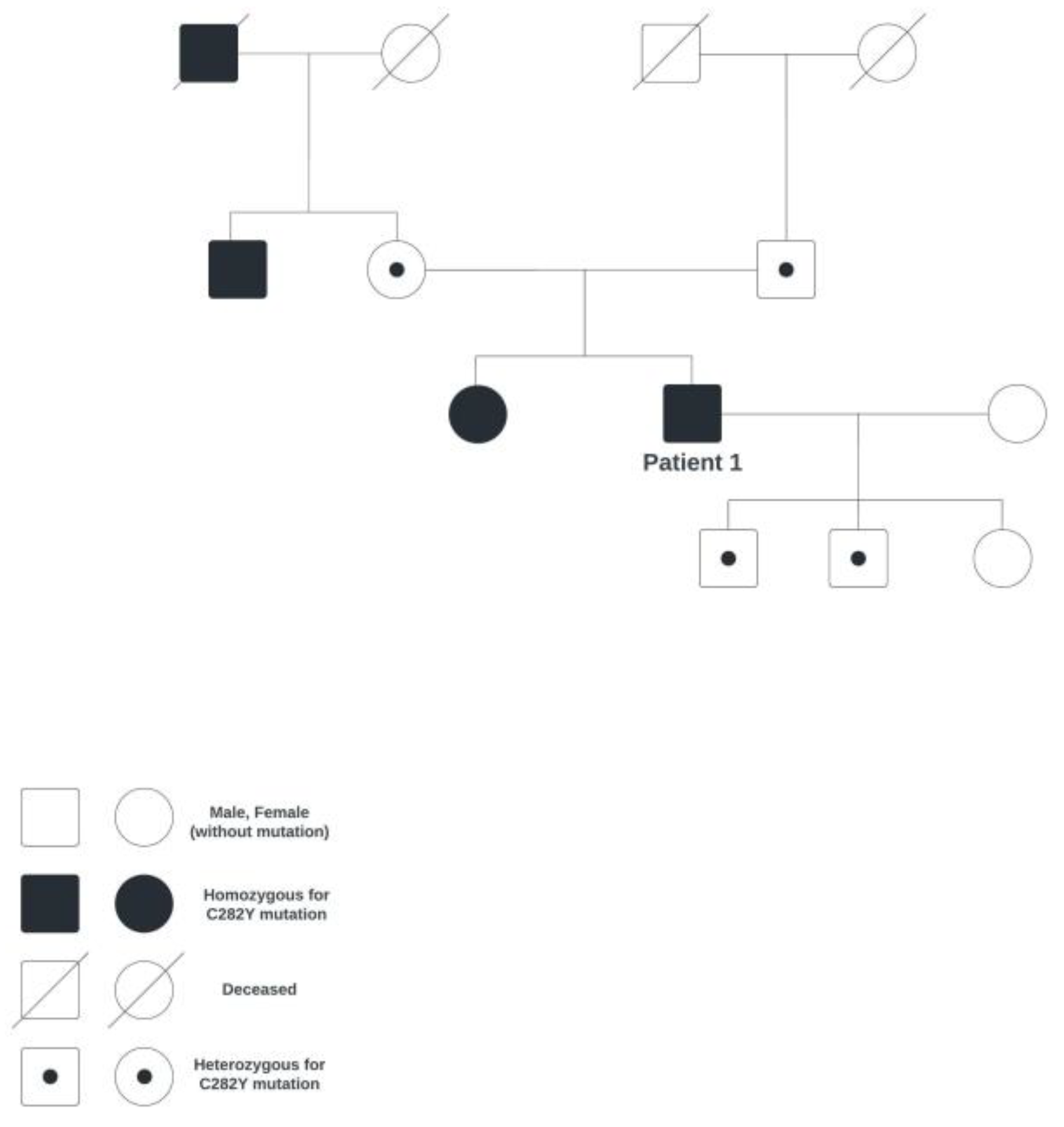

Patient 1

A 63-year-old male patient came to the Department of Ophthalmology due to blurred vision and diplopia, on account of which the patient has been monitored. For the past 11 years, he has been monitored due to hereditary hemochromatosis (homozygote for the C282Y mutation; the family genetic tree is shown in

Figure 1). Since then, whole-blood phlebotomy has been indicated to take place every three months, along with a check-up of the blood count and ferritin.

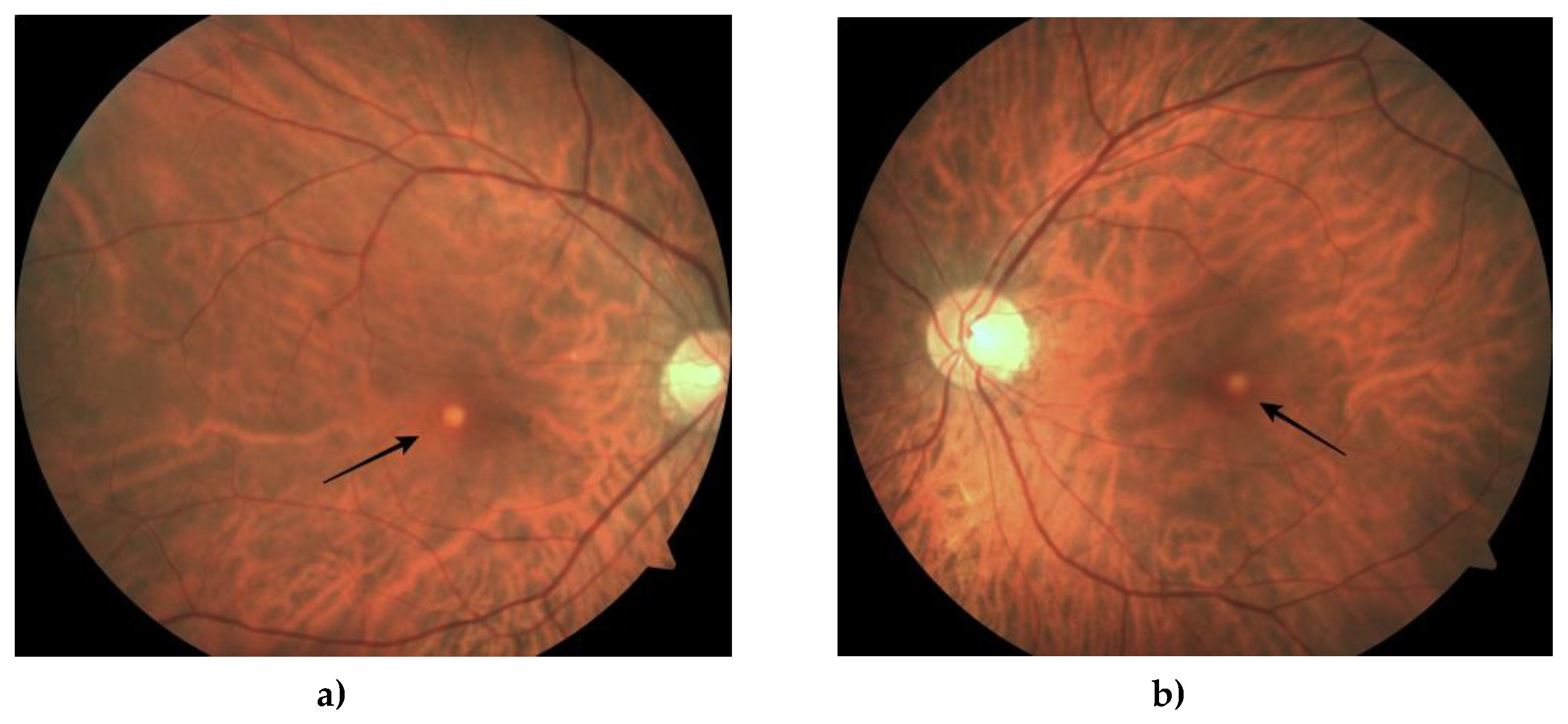

The first eye check-up revealed that the best-corrected visual acuity was 1.0 right and 1.0 left (on a LogMAR chart). An examination using the slit lamp only showed an incipient cataract on the posterior pole of the left lens and normal intraocular pressure. A fundus examination revealed a yellowish lesion in the macula’s center (

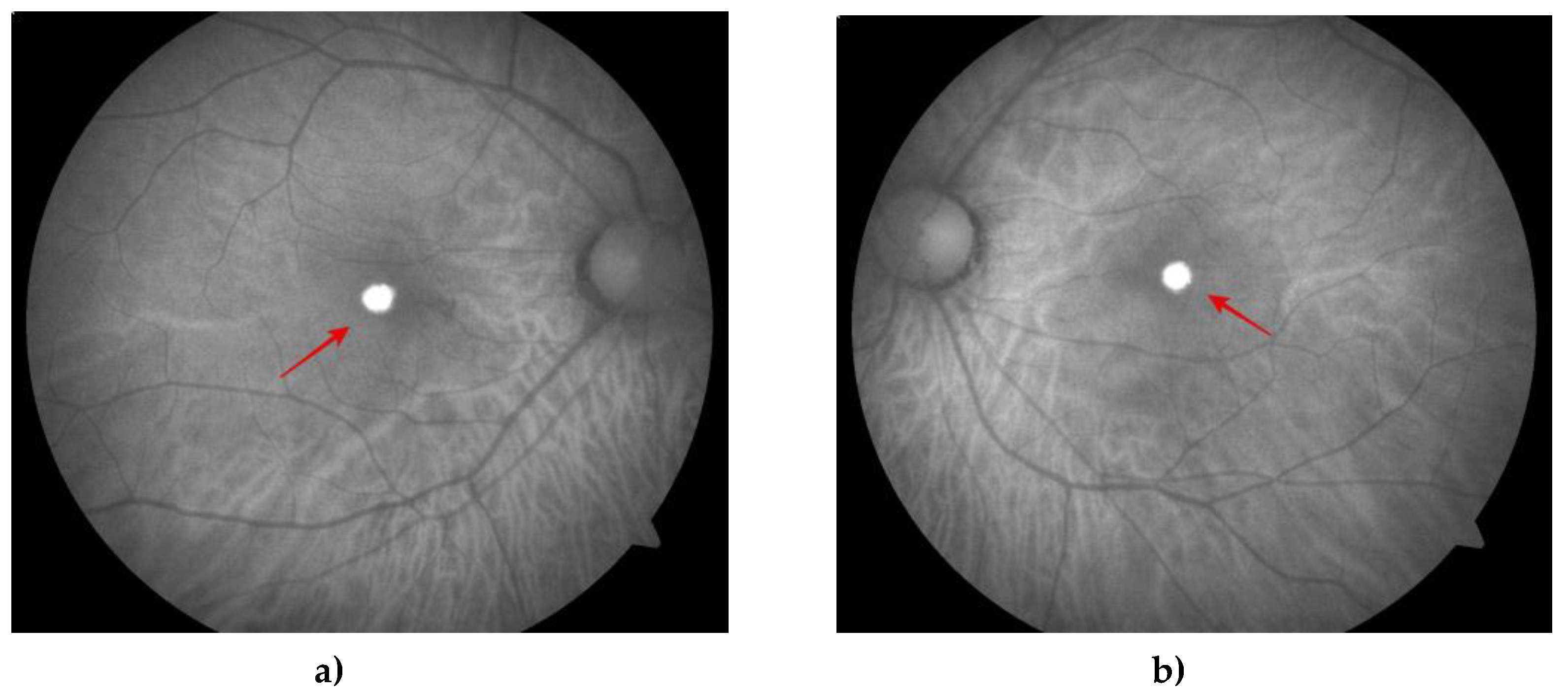

Figure 2). Fundus autofluorescence (FAF) showed autofluorescent lesions in the corresponding place (

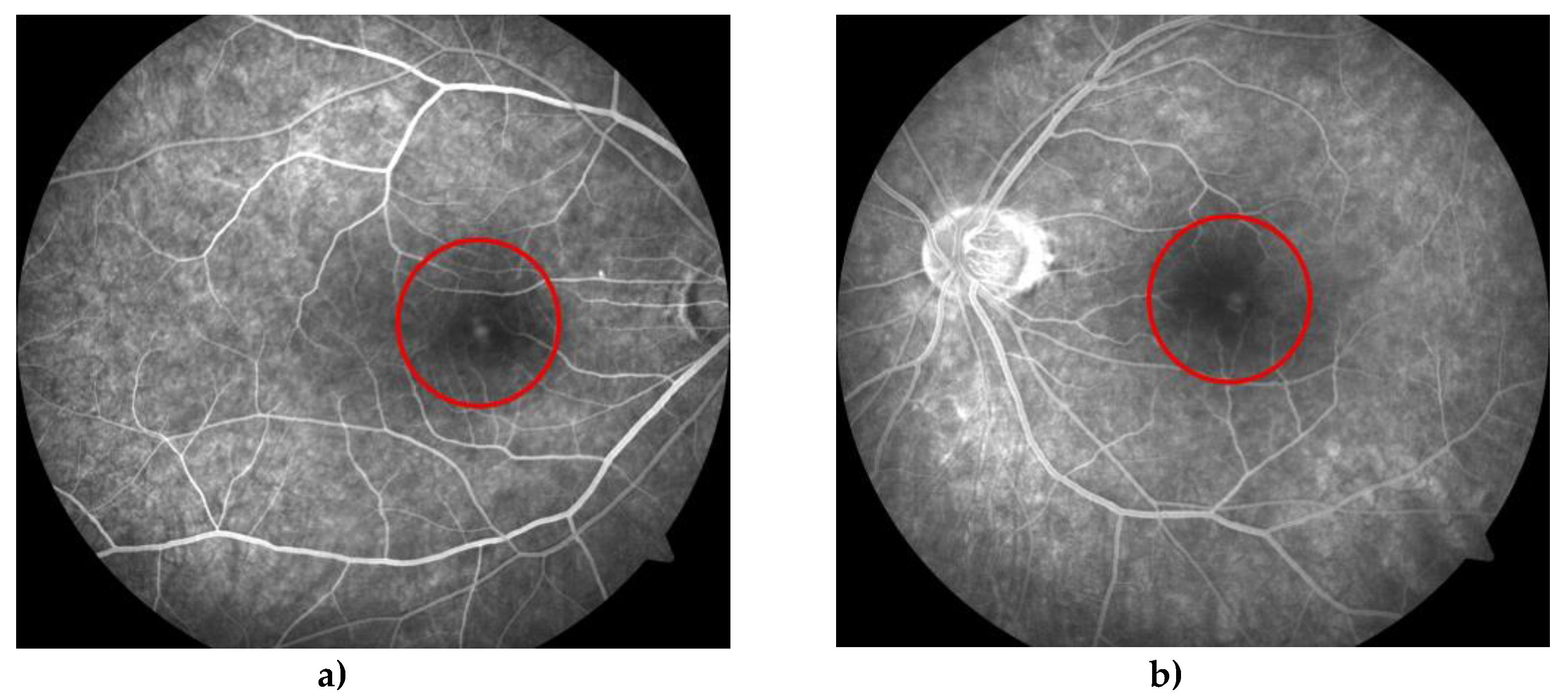

Figure 3), whereas fluorescein fundus angiography (FFA) showed early fluorescence in the fovea due to the window effect and minor hypofluorescence (

Figure 4). Optical coherent tomography (OCT) showed subfoveal, oval, dense deposits and disorders of the ellipsoid zone and external limiting membrane (

Figure 5).

An electroretinogram (ERG) revealed a normal retinal response. The electrooculogram (EOG) was normal, along with the Arden ratio of 3/2.5. Multifocal electroretinogram (Mf-ERG) showed diffusive and emphasized amplitude reduction of the P1 waves for both eyes (

Figure 6). The visual field was slightly concentrically narrowed (

Figure 7). The patient underwent clinical exome sequencing (exome LG235), which confirmed the C282Y mutation of the HFE gene, and hereditary macular dystrophy was ruled out. Over five years of monitoring, visual acuity remained stable, and the lesions in the macula were unchanged.

Patient 2

A 47-year-old male patient came to the Department of Ophthalmology due to visual difficulties in the form of a black blur in the center of the visual field of the right eye. The patient has been monitored for dizziness by a neurologist, who recommended taking an MRI of the brain, which showed no pathological findings. The patient was examined at the Department of Hematology due to higher values of ferritin and iron. In June 2015, hereditary hemochromatosis (homozygote for the C282Y mutation; the family genetic tree is shown in

Figure 8) was diagnosed, on account of which the patient underwent erythrocytapheresis every three months.

The eye check-up showed a decrease in visual acuity in both eyes. The best-corrected visual acuity was 0.8 right and 0.7 left (on a LogMAR chart). Examination with the slit lamp showed a normal anterior segment with normal intraocular pressure. A fundus examination revealed yellowish lesions located centrally in both maculae, with RPE changes in the right eye (

Figure 9). The FAF showed oval autofluorescent lesions in the corresponding place (

Figure 10), whereas the FFA showed a hypofluorescent blocking lesion centrally in the macula, surrounded by a narrow zone of early fluorescence due to the window effect (

Figure 11). OCT showed subfoveal disorders of the RPE, a lesion of the ellipsoid zone, and external limiting membrane lesions, as well as deposits in the external layers of the macula (

Figure 12).

ERG revealed normal retinal response, and EOG was normal as well, along with the Arden ratio of 2.1/2.3. Despite foveal structural changes, Mf-ERG showed the amplitude of P1 waves within normal limits in both eyes (

Figure 13). The visual field was slightly concentrically narrowed (

Figure 14). The patient underwent clinical exome sequencing (exome LG235), which confirmed the C282Y mutation of the HFE gene, and hereditary macular dystrophy was ruled out. Over three years of monitoring, visual acuity remained stable, and the lesions in the macula were unchanged.

3. Discussion

We presented two patients with visual difficulties manifested as blurred vision and diplopia in the first patient and black blur in the visual field in the second patient. Both patients underwent clinical examinations involving multimodal imaging and electrodiagnostic methods, which established pseudovitelliform macular degeneration in the center of the macula for both of them. An important fact is that the findings on the EOG for both patients were within normal limits, with an Arden ratio of 2.1/2.3 in one patient and 3/2.5 in the other patient, thereby allowing us to partially exclude the possibility of Best disease. The results of clinical exome sequencing of LG235 completely ruled out the possibility of Best's disease, revealing that there is no gene mutation responsible for any hereditary macular dystrophy.

Taking into account their earlier known long-term diagnosis of hereditary hemochromatosis as a homozygote for the C282Y mutation, in the absence of other comorbidities, our presumption is that it potentially led to the mentioned morphological and functional disorders of the retinal pigment epithelium, which in turn caused structural changes in the macula in both patients.

It is a known fact that iron has an important role in the functioning of the RPE, primarily as a cofactor of the RPE65 protein, which is important for retinoid metabolism [

8], the functioning of the guanylate cyclase during the synthesis of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) in phototransduction, the functioning of the fatty acid desaturase in synthesizing lipids for the new disk membranes of the outer segments of photoreceptors, their phagocytosis, and the lysosomal activities of the RPE [

8,

9], thereby ensuring photo-excitability [

6]. Moreover, iron is crucial for the functioning of several enzymes responsible for neurotransmitter homeostasis [

8]. Therefore, disorders of iron metabolism may lead to pathological functions and morphological changes in the retina.

When considering HH with mutations of the HFE gene, there is a disorder in the expression of the HFE protein, which is predominantly found on the basolateral side of the RPE, and there, binding onto TfR1 and TfR2s, it participates in controlling the metabolism and iron homeostasis [

6,

10]. It is clear that the iron homeostasis disorder leads to a series of pathological changes, starting from iron overload given the other tissues affected by hemochromatosis, so too in eye tissue [

11], which can be deduced from the study with Hfe-/- mice [

6]. In addition to the accumulation, morphological changes to the RPE also occur in terms of hypertrophy and/or hyperplasia [

7], which is not only inherent to pathological processes in HH but also in aceruloplasminemia with disorders of the ceruloplasmin ferroxidase enzyme [

13] and in age-related (senile) macular degeneration [

14]. Degenerative changes in the mentioned states can be attributed to iron overload, which leads to the onset of very reactive hydroxyl radicals through Fenton reactions, thus creating oxidative stress and damage [

15].

The mentioned pathological processes could explain the changes in the macula of our patients. The described thickening may conform to the accumulation of metabolic products and non-phagocytosed outer segments of photoreceptors, which are usually phagocytosed in a physiological state. Outer segments of photoreceptors remain accumulated in the external layers of the retina due to dysfunction of phagocytosis and transport through the RPE. Damage to the RPE (seen as the window effect on FFA (

Figure 4 and

Figure 11) is attributed to iron overload in RPE cells and intercell spaces and degeneration of RPE cells, which could explain other components of the macular lesion. Structural changes are also visible as disordered continuity of the retinal pigment epithelium and migration of RPE cells (

Figure 5 and

Figure 12).

Besides actual exposure to the oxidative effects of hydroxyl radicals, we believe that the duration of exposure to oxidative stress is an essential factor in the development of morphological changes as well as functional changes in the retina. In support of the development of morphological changes with a longer duration of tissue exposure to oxidative stress are the described morphological changes for 18-month-old Hfe-/- mice, whereas for Hfe-/- mice 4, 8, and 12 weeks old, no morphological changes were found [

7]. Functional changes in the retina could explain the condition of our two patients. Specifically, the 62-year-old patient with subjective visual impairment exhibiting poor eyesight (Mf-ERG) exhibited a poorer response of the cones, along with diffusive and emphasized amplitude reduction of P1 waves in both eyes (

Figure 6), while the 45-year-old patient with the black blur in the visual field of the right eye showed a slightly reduced response of the peripheral cones with physiological amplitude of P1 waves in both eyes (

Figure 13). The reduction of the amplitude of P1 waves could indicate that iron toxicity and oxidative stress caused retinal dysfunction at the level of photoreceptors and bipolar cells [

8]. Considering that the cones may be more sensitive to oxidative stress from other parts of the retina [

16], there exists a possibility that the exposure duration to oxidative stress has great significance in the onset of morphological and functional changes to the retina.

4. Conclusion

Finally, both patients' visual examinations revealed morphological and functional changes in the macula. We attributed them solely to iron accumulation and oxidative stress caused by the pathophysiological processes of hereditary hemochromatosis since the patients were not given chelating agents. In addition to the aforementioned processes, we would like to emphasize that further deterioration of the function and morphology of the macula is expected due to the duration of the primary disease.

Author Contributions

All authors attest that they meet the current ICMJE criteria for authorship. Conception and design (N.V., A.V.), data extraction (K.M., I.P., M.V.), manuscript preparation (A. V., M.V., T. J.), final approval (N.V., T.J.). All authors have seen and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of University hospital center Zagreb (02/21-JG (Class: 8. 1-21/85-2)).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The original data generated and analyzed for this study are included in the published article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Distante, S.; Robson, K.J.H.; Graham-Campbell, J.; Arnaiz-Villena, A.; Brissot, P.; Worwood, M. The origin and spread of the HFE-C282Y haemochromatosis mutation. Hum Genet. 2004, 115, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frazer, D.M.; Anderson, G.J. The orchestration of body iron intake: how and where do enterocytes receive their cues? Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2003, 30, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilling, L.C.; Tamosauskaite, J.; Jones, G.; Wood, A.R.; Jones, L.; Kuo, C.-L.; et al. Common conditions associated with hereditary haemochromatosis genetic variants: cohort study in UK Biobank. BMJ. 2019, 364, k5222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Nicola, M.; Barteselli, G.; Dell'Arti, L.; Ratiglia, R.; Viola, F. Functional and structural abnormalities in Deferoxamine retinopathy: a review of the literature. Biomed Res Int. 2015, 2015, 249617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellsmith, K.N.; Dunaief, J.L.; Yang, P.; Pennesi, M.E.; Davis, E.; Hofkamp, H.; et al. Bull’s eye maculopathy associated with hereditary hemochromatosis. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2020, 18, 100674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnana-Prakasam, J.P.; Martin, P.M.; Smith, S.B.; Ganapathy, V. Expression and function of iron-regulatory proteins in retina. IUBMB Life. 2010, 62, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnana-Prakasam, J.P.; Thangaraju, M.; Liu, K.; Ha, Y.; Martin, P.M.; Smith, S.B.; et al. Absence of iron-regulatory protein Hfe results in hyperproliferation of retinal pigment epithelium: role of cystine/glutamate exchanger. Biochem J. 2009, 424, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahandeh, A.; Bui, B.V.; Finkelstein, D.I.; Nguyen, C.T.O. Effects of Excess Iron on the Retina: Insights From Clinical Cases and Animal Models of Iron Disorders. Front Neurosci. 2022, 15, 794809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Lukas, T.J.; Du, N.; Suyeoka, G.; Neufeld, A.H. Dysfunction of the Retinal Pigment Epithelium with Age: Increased Iron Decreases Phagocytosis and Lysosomal Activity. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009, 50, 1895–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, P.M.; Gnana-Prakasam, J.P.; Roon, P.; Smith, R.G.; Smith, S.B.; Ganapathy, V. Expression and Polarized Localization of the Hemochromatosis Gene Product HFE in Retinal Pigment Epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006, 47, 4238–4244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, G.; Dymock, I.; Harry, J.; Williams, R. Deposition of melanin and iron in ocular structures in haemochromatosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1972, 56, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, M.; Jankovic, J. Neurodegenerative disease and iron storage in the brain. Curr Opin Neurol. 2004, 17, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolkow, N.; Song, Y.; Wu, T.-D.; Qian, J.; Guerquin-Kern, J.-L.; Dunaief, J.L. Aceruloplasminemia: retinal histopathologic manifestations and iron-mediated melanosome degradation. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011, 129, 1466–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunaief, J.L. Iron Induced Oxidative Damage As a Potential Factor in Age-Related Macular Degeneration: The Cogan Lecture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006, 47, 4660–4664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueda, K.; Kim, H.J.; Zhao, J.; Song, Y.; Dunaief, J.L.; Sparrow, J.R. Iron promotes oxidative cell death caused by bisretinoids of retina. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018, 115, 4963–4968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, B.S.; Symons, R.C.A.; Komeima, K.; Shen, J.; Xiao, W.; Swaim, M.E.; et al. Differential Sensitivity of Cones to Iron-Mediated Oxidative Damage. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007, 48, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Family genetic tree of patient 1.

Figure 1.

Family genetic tree of patient 1.

Figure 2.

Fundus photography of the right (a) and left (b) eye shows a depigmented yellow lesion (black arrow) in the macula.

Figure 2.

Fundus photography of the right (a) and left (b) eye shows a depigmented yellow lesion (black arrow) in the macula.

Figure 3.

Fundus autoflourescence (FA) shows an oval depigmented autofluorescent lesion (red arrow) in the center of the macula of the right (a) and left (b) eye.

Figure 3.

Fundus autoflourescence (FA) shows an oval depigmented autofluorescent lesion (red arrow) in the center of the macula of the right (a) and left (b) eye.

Figure 4.

Fluorescein fundus angiography (FFA) shows early fluorescence in the corresponding place due to the window effect of the right (a) and left (b) eye. (red circles).

Figure 4.

Fluorescein fundus angiography (FFA) shows early fluorescence in the corresponding place due to the window effect of the right (a) and left (b) eye. (red circles).

Figure 5.

Optical coherent tomography (OCT) shows a three-dimensional subfoveal, hyperreflective lesion (yellow circles) in the outer layers of the macula in the right (a) and left (b) eye.

Figure 5.

Optical coherent tomography (OCT) shows a three-dimensional subfoveal, hyperreflective lesion (yellow circles) in the outer layers of the macula in the right (a) and left (b) eye.

Figure 6.

Multifocal electroretinogram (Mf-ERG) showing diffusive and emphasised amplitude reduction of the P1 waves (blue circles) and emphasised reduction of cone response (red circles) in the macula in both the right (a) and left (b) eye.

Figure 6.

Multifocal electroretinogram (Mf-ERG) showing diffusive and emphasised amplitude reduction of the P1 waves (blue circles) and emphasised reduction of cone response (red circles) in the macula in both the right (a) and left (b) eye.

Figure 7.

Slightly concentrically narrowed visual field for the right (a) and left (b) eye.

Figure 7.

Slightly concentrically narrowed visual field for the right (a) and left (b) eye.

Figure 8.

Family genetic tree of patient 2.

Figure 8.

Family genetic tree of patient 2.

Figure 9.

Fundus photography of the right (a) and left (b) eye shows a depigmented yellow lesion (black arrow) in the macula.

Figure 9.

Fundus photography of the right (a) and left (b) eye shows a depigmented yellow lesion (black arrow) in the macula.

Figure 10.

FA showing a partially depigmented autofluorescent lesion (red arrow) in the center of the macula of right (a) and left (b) eye.

Figure 10.

FA showing a partially depigmented autofluorescent lesion (red arrow) in the center of the macula of right (a) and left (b) eye.

Figure 11.

FFA shows early fluorescence in the peripheral part of the lesion due to the window effect and blockage in the center of the lesion due to pigment accumulation (clumping) in the right (a) and left (b) eye. (red circles).

Figure 11.

FFA shows early fluorescence in the peripheral part of the lesion due to the window effect and blockage in the center of the lesion due to pigment accumulation (clumping) in the right (a) and left (b) eye. (red circles).

Figure 12.

OCT shows damage to the RPE, deposits of hyperreflective material, and pigment migration toward the inner layers of the macula of the right (a) and left (b) eye.

Figure 12.

OCT shows damage to the RPE, deposits of hyperreflective material, and pigment migration toward the inner layers of the macula of the right (a) and left (b) eye.

Figure 13.

Mf-ERG showing amplitude of P1 waves within physiological limits for both eyes and discrete reduction of cone response more to the periphery (red circle) in the right eye (a), and normaln cone response in the left eye (b).

Figure 13.

Mf-ERG showing amplitude of P1 waves within physiological limits for both eyes and discrete reduction of cone response more to the periphery (red circle) in the right eye (a), and normaln cone response in the left eye (b).

Figure 14.

Slightly concentrically narrowed visual field for both the right (a) and left (b) eye.

Figure 14.

Slightly concentrically narrowed visual field for both the right (a) and left (b) eye.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).