1. Background

Burnout is a specific syndrome that is a consequence of prolonged exposal to occupational stress, and it is primarily specific for occupations featured by working with people in emotionally challenging situations [

1]. Christiana Maslach gave a multidimensional definition of job burnout and defined it as “a psychological syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and a lowered sense of personal accomplishment that can be observed in people working with others in a certain specific manner” [

2]. Three key aspects of the burnout are emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and a diminished sense of personal accomplishment (PA), which occur as a response to chronic stress at jobs related to direct working with people.

EE is featured by a sense of emotional overextension as a result of work; depersonalisation is featured by emotional indifference and dehumanization of service recipients, and the diminished sense of personal accomplishment is featured by the sense of professional stagnation, incapability, incompetence and unfulfillment. DP refers to the development of insensitive and cynical attitude towards people who are service recipients, negative attitude towards work, as well as the loss of sense of own identity. The diminished sense of PA refers to negative self-assessment of competences and accomplishments at a workplace, and the symptoms are visible as a lack of motivation to work, decline in self-esteem and general productivity [

3,

4].

Private security refers to the security protection services that private security organizations provide to control crimes, protect lives and other assets, and to maintain order at their employers’ facilities [

5]. The private security sector is a set of registered private companies specializing in providing commercial services to domestic and foreign clients regarding the protection of people, property, and objects in accordance with the law [

5]. Private security agencies started emerging in the late 20

th century achieving real expansion in the beginning of the 21

st century. In the most Western countries, private security agencies are responsible for ensuring public order, protecting critical national infrastructures, banks, embassies, and airports [

6]. Private security officers also perform a variety of tasks that public police do not usually perform such as surveillance activities, information protection, and risk management [

5,

6].

In developed countries with a long tradition of private security protection such as the United States of America (USA), Great Britain and France these organizations have an important position within the system of national security [

7]. There are about 1.7 million employees in the private security sector in the European Union (EU) [

8] and about 2 million in the USA [

9] and there are about 40 000 people employed in this sector in the Republic of Serbia [

10,

11,

12,

13].

Working in the private security sector is most similar to police work in the most Western countries, security employees have almost the same responsibilities and perform similar tasks [

11]. The basic difference between state police officers and private security officers is reflected in the fact that police officers have legal power delegated by the state [

12]. On the other hand, private security employees do not have the status of authorized officers although they have powers similar to police, but they apply them in protected areas and in specific circumstances. Private security sector employees participate less in the decision making regarding work organization, they have less training than police officers and are generally less valued by society [

10,

11,

12,

13]. It is known that the private security officers receive less training than state police officers [

14]. Cihan (2016) added, in many cases, the private security officers receive inadequate training [

15].

The main characteristics of the professional private security sector in Central Serbia are: this is the third largest group of people under arms with about 40,000 employees, employees have different levels of training and different levels of education, and low social and economic status. Employees in the professional private security sector are exposed to various risk factors that can cause stress for an individual. In a country such as Serbia, which has undergone economic, political, and social reforms, as well as military and police reforms, a somewhat different hierarchy is expected with regard to job stressors, compared to developed countries. It is impossible to remove all the workplace stressors within a private company but it is necessary to identify the stressors in order to reduce exposure and prevent the occurrence and development of burnout syndrome [

16].

Burnout has serious professional and personal consequences, including lack of professionalism (often sick-leaves, reduced efficiency at work, lack of interest, non-collegiality) [

17], and problems in communication with close persons, divorces, losing friends, alienation, aggressiveness privately [

17,

18] and has negative impact on the employees’. Several studies conclude that employees with higher levels of burnout are more likely to suffer from a variety of physical health problems such as musculoskeletal pain, gastric alterations, cardiovascular disorders, headaches, increased vulnerability to infections, as well as insomnia and chronic fatigue [

19,

20,

21]. Jackson and Maslach (1982) explained security officers and their families pay emotional price for the officers’ occupational stress because they often take home the tension they suffer at work. Officers go home while experiencing feelings of anger, emotions, tension, and anxiety, and usually in complaining mode [

22].

The objective of the study was to analyze the burnout syndrome and the quality of life among security employees of the professional private security sector in Central Serbia.

2. Material and Method

2.1. Study Design

The study included security staff employed at private agencies in seven cities in Central Serbia. The representative sample size was 439, the study strength was 80%, and the type 1 error probability α of 0.05. The study included only 353 questionnaires that were completely filled out. The study was performed in the period from March 3, 2019 to April 30, 2019.

Study inclusion criteria were: adults 18-65 years of age, citizens of the Republic of Serbia, full-time employees, licensed to work in private security and working longer than 12 months. Exclusion criteria were: staff in the process of obtaining the license, discontinuity at work longer than one year, long-term sick leaves or multiple changes of workplace in the past 5 years, respondents recently exposed to major psychophysical trauma regardless of the professional environment (illness or death of a close person, divorce ...), refusal to participate in the study.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Pristina with temporary seat in Kosovska Mitrovica by the Decision № 09-972-1 dated September 10, 2018.

2.2. Questionnaires

A semi-structural epidemiological questionnaire with 20 questions has been specially designed for this research, to gather information the basic socio-demographic information (sex, age, marital status and number of children, level of education, length of service, work experience and length of service at any of the managerial positions, shift work, field work, specific features of a workplace). One question on a three-point Likert scale examined the level of the respondents’ satisfaction with the conditions of their work. The respondents were offered a possibility to present in an open question any complaints on the work conditions.

2.1.1. The Maslach Burnout Inventory Human Services questionnaire

It is an internationally accepted burnout measuring standard that measures 3 burnout subscales and it is often used as a model for the evaluation of validity of other burnout risk assessment scales. We have used the questionnaire for staff employed at institutions who are in direct contact with people (Human Services Survey, MBI-HSS) with 22 variables [

24].

In the Republic of Serbia Licenses for the Maslach Burnout Inventory Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS) questionnaire and the evaluation key as well as the usage permission were obtained directly from the current license owners–the SINAPSA EDITION Company according to license No. 2/2018 dated May 9, 2018.

The managers of private security agencies provided written approvals for the research. All the respondents were informed in detail about the research and they signed the consents to participate in the study.

MBI-HSS consists of the total of 22 questions that are afterwards used in the calculation of three subscales measuring different occupational burnout aspects:

Emotional exhaustion (EE) – measures the sense of emotional strain and exhaustion caused by work.

Depersonalization (DP) – measures the inexistence of sense and impersonal reaction towards the recipient of services, help, treatment or tutoring, or a sense of discomfort caused by exertion.

Personal accomplishment (PA) or lack of PA – measures the experience of competence and success in working with people, or a sense of competition and job satisfaction.

It is a self-administered questionnaire. Each question consists of a series of statements expressing the degree of agreement with the expressed statements, and the response categories are provided through the 7-point Likert scale from 0 (never) to 6 (every day), (or 0 – never, 1 – once a year or less, 2 – once a month and less, 3 – few times a month, 4 – once a week, 5 – a few times a week, 6 – every day).

The total score of the each respondent was obtained by summing up the matrix with a specific key for each of the three previously mentioned subscales, and the total degree of occupational burnout is represented by a comprehensive scale calculated based on a precise formula. High level of burnout at work is reflected in high scores on the emotional exhaustion and depersonalization subscales and low scores on the personal accomplishment subscale. This means that high scores on the EE and DP scales contribute to the burnout syndrome, while high scores on the professional accomplishment scale diminishes it. Medium level of burnout is a reflection of means on all three subscales. Low level of burnout at work is reflected in low scores on the EE and DP subscales and high scores on the PA subscale. The PA scale is relevant only if confirmed with the EE or DP scale.

2.2.2. Short Form 36 Health Survey- (SF-36)

SF-36 is the most commonly used instrument that measures subjective health, i.e., the health-related quality of life (HRQoL). The questionnaire is a generic instrument for measuring health status and quality of life. It is standardized and very sensitive for assessing the overall impact of health on the quality of life. It consists of 36 questions covering a period of four weeks. It is designed to analyze self-ranking individual perception of health, functional status and sense of well-being [

24]. The questions cover eight domains in the field of health: physical functioning, limitations due to physical health, body pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, limitations due to emotional problems and mental health. When the total of each individual domain is calculated, the next step is calculating the Physical Health Composite Score (PHC) and Mental Health Composite Score (MHC), which are related to the quality of life.

The eight subscales of this questionnaire are used to assess the category (dimension) of functional health and the sense of well-being, four for physical and four for mental status. Very important for measuring the physical health are the following dimensions: physical functioning, physical role, body pain, and general health. All individual scores and both composite scores can have values ranging from 0 to 100, where 0 is very poor quality of life and 100 is ideal quality of life resulting from good physical and mental health. Composite scores of physical and mental health are used to calculate the total quality of life (TQL) score. The scales of vitality and general health have a good validity and the questionnaire is used to compare different conditions and diseases and it is considered the “gold standard” in assessing the quality of life related to health.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

All the analyses were done in the SPSS-version 22 program package. We calculated means, odds ratio (OR), confidence intervals (CI), variance analysis (ANOVA). Analysis of variance for repeated measures (Repeated Measures ANOVA) was applied to test the statistical significance of changes in values of indicators of the quality of life. For the comparison of the numerical characteristics we used the Student's t-test. The Chi-squared test was used to compare frequencies between groups, or Fisher test when the expected frequency is less than 5 in one of the cells. An univariate and then a multivariate logistic regression analysis were used to assess the relationship between the burnout and the characteristics of the respondents obtained from the questionnaires. Spearman correlation analysis was used to assess the association of descripiv characteristics and burnout syndrome and the Spirman's coefficient of rank correlation was calculated (r), too. The p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-descriptive characteristics of the respondents

A total of 353 respondents (330 male and 23 female) participated in the research. The Response rate was 80%. Men represent 93.5% of all the respondents and they were significantly older than women: 44.09±11.44 vs. 36.91±7.92 (F=8.752; p=0.003).

224 (64.3%) respondents were married; about one third did not have children (33.7%), and more than half of the respondents had completed high school (54.7%). The least of the employees had a university degree (7.6%). There were 300 (78.00%) who were in the service, about 22.7% held managerial positions, 288 (81.6%) worked in shifts, and most of the respondents, as much as 277 (78.5%), worked from 8 to 12 hours a day.

3.2. Burnout in security emplyoees in the private sector

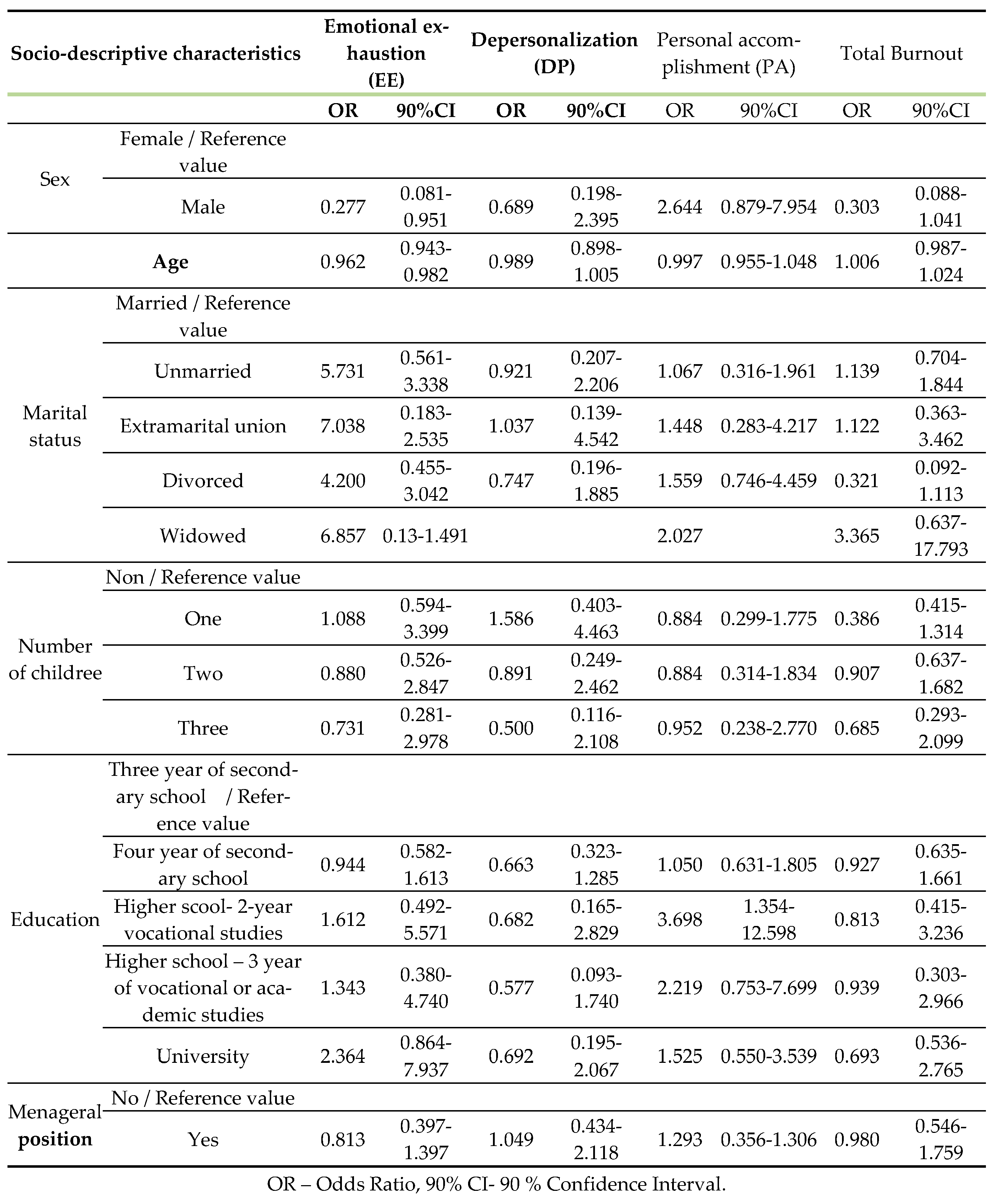

For each subscale of burnout EE, DP, PA and for the total burnout multilogistic regression analysis was done and the results are presented in

Table 1.

Table 1 shows the results of EE subscale modelling with the application of multivariate logistic regression analysis in regard to the independent variables as follows: sex, age, marital status, number of children, education, length of service, service in the company, shift work, working hours, managerial function and working conditions.

The independent variable “sex” was found to be statistically significant at the p=0.10 level, its cross-ratio (namely the male category in relation to the reference category female) was 0.277, while its corresponding 90% confidence interval (CI) for the cross-ratio is 0.098-0.780. Based on this, it was determined that employed men were 82% less likely to exhibit EE compared to employed women.

The independent variable “age” of the employees also showed a statistically significant effect on the high degree of EE in the examined group (p<0.001). The chances that an employee will have a high degree of EE increases with age, and the ratio was 0.962, with 90% CI from 0.946 to 0.979, with each additional year of life, EE increases by 3.8%.

The dependent variable “depersonalisation” was transformed into a binary type. The reference category is represented by low and moderate level of depersonalisation. The effect of dependent variables on the independent variable – level depersonalisation has not been determined.

The dependent variable “personal accomplishment” was transformed into a binary type. The reference category is represented by high and moderate level of PA. The sex of the respondents stood out as a significant variable in the dependent PA variable modelling. The cross-ratio of “male” in comparison to the reference category “female” amounts to 2.644 and the significance is at the level of p= 0.10, while its corresponding 90% confidence interval for the cross-ratio is 0.879 - 7.954. If a respondent is male, the probability that he will manifest the burnout in the form of lowered PA is reduced by 164% in comparison to female respondents.

The respondents’ education also stood out as a significant variable in the dependent PA variable. The cross-ration of “university” education in comparison to the reference category of “secondary three-year school” amounts to 3.698 and the significance is at the level of p=0.10, while its corresponding 90% confidence interval for the cross-ration amounts to 1.237 – 11.051. If a respondent has university education, the probability that they will manifest the burnout in the form of lowered PA is reduced by 269% in comparison to the respondents with three-year secondary school.

Table 1 shows the results of PA subscale modelling with the application of multivariate logistic regression analysis in regard to the independent variables as follows: sex, age, marital status, number of children, education, length of service, service in the company, shift work, working hours, managerial function and working conditions.

The sex of the respondents stood out as a significant variable for the PA subscale. The cross-ratio of “male” in comparison to the reference category “female” amounts to p=2.644 and the significance was at the level of p= 0.10, while its corresponding 90% CI for the cross-ratio was 0.879-7.954. If a respondent was male, the probability that he will manifest the burnout in the form of lowered PA is reduced by 164% in comparison to female respondents. The respondents’ education also stood out as a significant variable in the dependent PA variable.

The cross-ration of university education in comparison to the reference category of “secondary three-year school” amounts to 3.698 and the significance was at the level of p=0.10, while its corresponding 90%CI 1.237–11.051. If the respondent has university education, the probability that they will manifest the burnout in the form of lowered PA is reduced by 269% in comparison to the respondents with three-year secondary school.

Table 2 shows the average scores of the basic eight scales of the SF-36 questionnaire. Physical functioning (PF) was a domain with the highest average value (93.68), while the average score for vitality (VT) was 62.15 and for general health (GH) was 66.60.

Table 3 shows a composite score of PHC in relation to socio-descriptive characteristics of employees.

Compared to men, a significantly higher PHC score was observed in women (p=0.011) as well as in unmarried participants (p=0.001). PHC score was significantly higher in employees without children (p=0.001), compared to employees with children. Employees working in shifts had significantly higher average values of PHC score (p=0.005). Working hours had no significant impact on the PHC score (p=0.147) whereas the managerial position had a significant impact on the higher PHC score (p=0.009).

Table 4 shows composite MHC score in relation to socio-descriptive characteristics of employees.

There is no statistically significant difference in average values of MHC score in relation to sex of employees (p=0.071). Widows/widowers had a significantly lower MHC score compared to employees with different marital status (p=0.001). Employees without children or with one child had a significantly higher MHC score compared to employees with two or three children (p=0.049). The level of education had no significant impact on the average values of MHC score (p=0.598). Work in shifts (p=0.070), working hours (p=0.171) and managerial position (p=0.355) had no significant impact on the average values of MHC score.

Compared to women, men had a statistically significantly lower average score of the total quality of life (p=0.013). Married employees had a significantly lower TQL score compared to those who were not married (p=0.001). Widowed employees had statistically lowest TQL score. Employees without children or with one child had a significantly higher TQL score, compared to employees with two, three or more children (p=0.001).

Education did not have a significant impact on the average TQL score (p=0.160). Shift work has a statistically significant impact on the reduction of the average TQL score (p=0.007). Employees on managerial positions had a statistically significantly higher TQL score compared to the employees who did not hold managerial positions (p=0.034).

4. Discussion

According to the results of the multicenter study we conducted with a representative sample of employees in professional private security agencies in Central Serbia, out of the total number of responders, approximately one third (32.6%) had symptoms of burnout syndrome. In contrast to the “total burnout”, a much higher number of employees developed moderate or high level of burnout symptoms in individual subscales. In EE (high 66.3%, moderate 19.8%); in DP (high 82.4%, moderate 16.2%) and slightly more than one third of employees 34.5% had low PA, about one third 32.9% had moderate PA. Our study has shown that female sex and older age were associated with higher risk of total burnout and for the development of EE. Male sex, university education and managerial position were associated with higher PA and lower risk of of total burnout because this subscale is inversely correlated with the burnout. Male sex, marritual union, two and more childreen and direct contact with clients were significantly associated with lower quality of life of security employees. Widowed employees had statistically the lowest total quality of life score.

There are also different results in the literature according to which men are protected from EE if they are in an emotional relationship and women are at risk of developing EE if they have a family [

25]. Similar results as ours about in which the presence of EE subscale in burnout was the highest in participants presented in similar studies [

16]. Employed women, due to their responsibilities towards their family and their work, have difficulties in harmonizing professional and private obligations. In certain studies, women were found to be more prone to EE [

20,

21] while men were more susceptible to DP. State police officers who were in an emotional relationship were more prone to EE but had the experience of higher PA and there was no statistically significant difference between state police officers in the civil service who have children and those who do not have children or have fewer children, on the development of burnout [

18,

19,

20].

Sex does not seem to be a constant predictive factor for burnout. Some studies have shown that women suffer more from burnout than men [

25,

26], while others have proved that males report higher burnout scores [

27,

31]. Some other studies have also detected no difference in their level of burnout [

32]. According to findings of Ronen and Pines (2008) results negative te Brake et al. (2003) and Maccaaro (2011) male, sex, shift work and low score in relationships with superiors at working place were no significantly associated with women and burnout [

31]. There was higher percntage of burnout in males than in females. They pagged out this results on the fact that women have greater tendency to utilase emotion focused coping, theirs maller per support and grater work- familiy conflict [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35].

According to our results there were significantly more men than women and they were significantly older than women. Results of studies point to an inverse relationship between age and burnout, such that people will experience lower levels of total burnout as their age increases [

36,

37]. A systematic review of the determinants of burnout [

36] found a significant relationship between increasing age and increased risk of DP although on the other hand there is also a greater sense of PA. More than 60.0% of our respondents were married and about one third did not have children. In relation to marital status, emploeeys who are single (especially men) seem to be more exposed to burnout compared to those who live with a partner. However, such findings seem to be more appropriate in men, as in the case of working women, it constitutes an additional risk factor since working women are usually responsible for household chores and, therefore, this may pose a difficulty in reconciling personal and professional life.

More than a half of the respondents had completed secondary school and only 7.6% had a university degree. In the EU countries, there is a significantly greater number of employees with higher education and university degrees [

10]. In a similar study conducted with state police officers in Spain, there were almost twice as many employees with a university degree, compared to employees from our research [

38].

More than two thirds of the respondents were in the service as security officers and less than one fourth of the employees held managing positions. According to our results managerial position and higher education were protective factors in relation to the development of burnout in our study. A possible explanation could be the fact that managers are less exposed to direct contact with clients and potential attackers and usually they don’t work in shifts and had shorter working hours. According to a study conducted in Denmark, organizational factors are more significant than individual factors for the development of burnout syndrome [

39]. In this study, none of the descriptive characteristics of the participants had a statistically significant association with burnout.

Male sex, marritual union, two and more childreen and direct contact with clients were significantly associated with lower quality of life of security employees. Widowed employees had statistically the lowest total quality of life score. There are similar data in the literatute [

18,

19,

37,

40].

The possibility of developing job burnout among employees in the professional private security sector in the Republic of Serbia can be seen in a broader context by examining general values, political and economic opportunities, and instability in the region. Having in mind the specifics of the job, examination the socio-descriptive characteristics of candidates before employment is necessary and it would enable identification of persons at higher risk. In this way, a better selection of candidates for security jobs could be done and the risk of burnout could be prevented or reduced as well as the consequences and the employee's quality of life will be preserved. Monitoring employee job satisfaction, continuous improvement of work organization, continuous education of employees in security work and awareness of the burnout symptoms would enable timely treatment, rehabilitation, temporary job change and finally, permanent job change all with the aim of preserving health and life of employees.

5. Conclusions

About one third of employees had symptoms of total burnout. Female sex and older age were associated with higher risk of total burnout and for the development of emotional exhaustion. Male sex and higher level of education were associated with greater personal achievement. Male sex, university education and managerial position were associated with higher personal achievement and lower risk of of total burnout because this subscale is inversely correlated with the burnout. Characteristics such as male sex, marritual union, two and more childreen and direct contact with clients because they were significantly associated with lower quality of life of the employees. The accelerated development of the private security sector in the Republic of Serbia requires additional research of burnout and the quality of life of this group of employees.

Author Contributions

N.K.R.—writing drift, study design, acts as the corresponding author, D.R.V.—investigation, conceptualization, M.R.M.—methodology, made the database, Lj.K.M.—conceptualization, supervision, V.S.J.—methodology evaluation, critically evaluated the text of the manuscript, B.N.S.—investigation, critically evaluated the references, N.S.M.—formal analysis, study design, V.M.C.—investigation, critically evaluated the paper, E.M.M.-Z.—investigation, critically evaluated the results of analysis, D.S.G.—investigation, revised the data base, M.M.S.—investigation, software, Z.N.B.—software, investigation, administration, D.P.M.—investigation, resurces, S.A.O.—revised the manuscript, final approval of the manuscript version to submit. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

There is no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Pristina with temporary seat in Kosovska Mitrovica by the Decision № 09-972-1 dated September 10, 2018.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Abbreviations

WHO—World Health Organization

ICD—International Classification of Diseases

EE—Emotional Exhaustion

DP—Depersonalization

PA—Personal Accomplishment

MBI-HSS—Maslach Burnout Inventory Human Services Survey

SF-36—Short Form 36 Health Survey

TQL—Total Quality Life

PHC—Physical Health Composite Score-PHC

MHC—Mental Health Composite Score-MHC

OR—Odds Ratio

CI—Confidence intervals

ANOVA—Analysis of Variance

References

- Edú-Valsania, S.; Laguía, A.; Moriano, J.A. Burnout: A Review of Theory and Measurement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Buunk, B.P. Burnout: an overview of 25 years of research in theorizing. In: Schabracq MJ, Winnubst JAM, Cooper CL, editors. The Handbook of Work and Health Psychology. Chichester: Wiley (2003). p. 383–425. [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C. Burnout: A multidimensional perspective. In Professional Burnout: Recent Developments in Theory and Research; Schaufeli, W.B., Maslach, C., Marek, T., Eds.; Taylor and Francis: Washington, DC, USA, 1993; pp. 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; van der Heijden, F.M.; Prins, J.T. Workaholism, burnout and well-being among junior doctors: The mediating role of role conflict. Work. Stress 2009, 23, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asomah, J.Y. Understating the development of private policing in South Africa. African Journal of Criminology and Justice Studies. 2017;10(1); 61-82. Available online: https://www.umes.edu.

- Baljak, M. The role of private security agency in the 21st century. Defendology 2015, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anđelković, S. Corporate security as a factor of national security [dissertation]. Educons University: Faculty of European Legal and Political Studies. 2015.

- Davidović, D.; Kešetović, Ž. Comparative overview of private security sector legislation in EU countries. SPZ [Internet]. 2009;53(2). Available online: https://www.stranipravnizivot.rs/index.php/SPZ/article/view/626.

- Goddard, S. The private military company: A legitimate international entity within modern confl ict, a thesis presented to the faculty of the U. S. Army command and General staff college. Fort Leavenworth: University of New South Wales. 2001.

- Thirion, A.P.; Pintar, C.A. Burnout in the workplace: A review of data and policy responses in the EU. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2018.

- Milošević, M.; Petrović, P. New and old challenges of the private security sector in Serbia. OEBS Mission in Serbia. 2015.

- Nikač, T.; Korajlić, N.; Ahić, J. Legal regulation of private security in the areas of the former SFRY, with reference to the latest changes in Serbia. Criminal themes 2013, 27–52. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Serbia. Law on Private Security. Official Gazette of RS. No. 104/2013-8, 42/2015-3, 87/2018-31.

- Cobbina, J.E.; Nalla, M.K.; Bender, K.A. Security officers’ attitudes towards training and their work environment. Security Journal 2016, 29, 385–399. Available online: http://www.palgrave-journals.com. [CrossRef]

- Cihan, A. The private security industry in Turkey: Officer characteristics and their perception of training sufficiency. Secur. J. 2013, 29, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veljkovic, D.R; Rancic, N.K.; Mirkovic, M.R.; Kulic, Lj.M.; Veroslava V. Stankovic , V.V.; Stefanovic, Lj.S.; et al. Burnout Among Private Security Staff in Serbia: A Multicentic Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Public Health, 07 May 2021 Sec. Occupational Health and Safety. 07 May. [CrossRef]

- Al-Mulla, K.I. Stress Reduction Strategies for Improving Private Security Officer Performance [dissertaition]. Eastern Kentucky University. Walden University. 2019. Available online: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations?utm_source=scholarworks.waldenu.edu%2Fdissertations%2F6298&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages.

- Queirós, C.; Passos, F.; Bártolo, A.; Marques, A.J.; da Silva, C.F.; Pereira, A. Burnout and Stress Measurement in Police Officers: Literature Review and a Study With the Operational Police Stress Questionnaire. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, R.J. Stressful Events, Work-Family Conflict, Coping, Psychological Burnout, and Well-Being among Police Officers. Psychol. Rep. 1994, 75, 787–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvagioni, D.A.J.; Melanda, F.N.; Mesas, A.E.; González, A.D.; Gabani, F.L.; De Andrade, S.M. Physical, psychological and occupational consequences of job burnout: A systematic review of prospective studies. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikwem, C. The Relationship of Job Stress to Job Performance in Police Officers. Walden University. 2017.

- Maslach, C.; Jakson, E. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Occup Behav. 1981, 2, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sample size calculator (online). Available online: https://www.chechkmarket.com/sample-size-calculator.

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E.; Leiter, M. Maslach Burnout Inventory. 3rd ed. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996.

- Ware, J.E.; Kosinski, M. SF-36 physical and mental health summary scales: a manual for users of version 1. 2nd ed. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2001.

- Aguayo, R.; Vargas, C.; Cañadas, G.R.; I De la Fuente, E. Are Socio-Demographic Factors Associated to Burnout Syndrome in Police Officers? A Correlational Meta-Analysis. An. Psicol. 2017, 33, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcon, G.; Eschleman, K.J.; Bowling, N.A. Relationships between personality variables and burnout: A meta-analysis. Work. Stress 2009, 23, 244–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olanrewaju, S.A.; Chineye, J.O. Gender differences in burnout among health workers in the Ekiti State University Teaching Hospital Ado-Ekiti. International Journal of Social and Behavioural Sciences 2013, 1, 112–121. Available online: http://www.academeresearchjournals.org/journal/ijsbs.

- Adekola, B. Gender differences in the experience of work burnout among university staff. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 4, 886–889. [Google Scholar]

- Adekola, B. Work burnout experience among university non- teaching staff: A gender approach. Int. Aha. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2012, 128–135. [Google Scholar]

- Purvanova, R.K.; Muros, J.P. Gender differences in burnout: A meta-analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 77, 168–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronen, S.; Malach Pines, M. Gender differences in engineers’ burnout. Equal Opportunities Int. 2008, 27, 677–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- te Brake, H.; Bloemendal, E.; Hoogstraten, J. Genderdifferences among Dutch dentists. Comm. Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2003, 31, 321–327. [Google Scholar]

- Maccacaro, G.; Di Tommaso, F.; Ferrai, P.; Bonatt, D.; Bombana, S.; Merseburge, A. The effort of being male: A survey on gender and burnout. Med. Lav. 2011, 102, 286–296. [Google Scholar]

- Violanti, J.M.; Owens, S.L.; Fekedulegn, D.; Ma, C.C; Charles, E.L.; Andrew, M.E. An Exploration of Shift Work, Fatigue, and Gender Among Police Officers The BCOPS Study. Workplace Health Saf. 2018, 66, 530–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adriaenssens, J.; De Gucht, V.; Maes, S. Determinants and prevalence of burnout in emergency nurses: A systematic review of 25 years of research. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52, 649–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P. New insights into burnout and health care: Strategies for improving civility and alleviating burnout. Med Teach. 2016, 39, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lastovkova, A.; Carder, M.; Rasmussen, H.M.; Sjoberg, L.; De Groene, G.J.; Sauni, R.; Vévoda, J.; Vevodova, S.; Lasfargues, G.; Svartengren, M.; et al. Burnout syndrome as an occupational disease in the European Union: an exploratory study. Ind. Health 2018, 56, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farfán, J.; Peña, M.; Topa, G. Lack of Group Support and Burnout Syndrome in Workers of the State Security Forces and Corps: Moderating Role of Neuroticism. Medicina 2019, 55, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Venâncio, L.; Coutinho, B.D.; Mont’alverne, D.G.B.; Andrade, R.F. Burnout and quality of life among correctional officers in a women’s correctional facility. Rev. Bras. de Med. do Trab. 2020, 18, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Results of multilogistic regression analyses of dependent variables ЕЕ, DP, PA and total burnout.

Table 1.

Results of multilogistic regression analyses of dependent variables ЕЕ, DP, PA and total burnout.

Table 2.

Average scores of the basic eight scales of the SF-36 questionnaire.

Table 2.

Average scores of the basic eight scales of the SF-36 questionnaire.

| Domains |

N |

Minimum |

Maximum |

|

SD |

| PF |

353 |

35.00 |

100.00 |

93.68 |

9.31 |

| RF |

353 |

.00 |

100.00 |

74.50 |

35.62 |

| RE |

353 |

.00 |

100.00 |

85.08 |

26.30 |

| VT |

353 |

20.00 |

100.00 |

62.15 |

17.19 |

| MH |

353 |

44.00 |

100.00 |

80.00 |

10.61 |

| SF |

353 |

25.00 |

100.00 |

82.11 |

15.77 |

| BP |

353 |

22.50 |

100.00 |

85.13 |

18.25 |

| GH |

353 |

5.00 |

100.00 |

66.60 |

19.27 |

Table 3.

Composite PHC score in relation to socio-descriptive characteristics of employees.

Table 3.

Composite PHC score in relation to socio-descriptive characteristics of employees.

| Characteristics |

N |

|

SD |

SEM |

95% CI |

Min |

Max |

| Lower |

Upper |

| Sex |

Male |

330 |

79.35 |

17.75 |

0.97 |

77.43 |

81.27 |

27.50 |

100.00 |

| Female |

23 |

88.99 |

11.79 |

2.45 |

83.89 |

94.09 |

49.38 |

100.00 |

| |

F=6.574; p=0.011 |

| Marital status |

Married |

227 |

76.72 |

18.34 |

1.21 |

74.32 |

79.12 |

27.50 |

100.00 |

| Unmarried |

87 |

88.23 |

12.78 |

1.37 |

85.50 |

90.95 |

38.75 |

100.00 |

| Extramarital union |

12 |

91.19 |

10.64 |

3.07 |

84.43 |

97.95 |

64.38 |

100.00 |

| Divorced |

23 |

79.05 |

12.65 |

2.63 |

73.58 |

84.52 |

57.50 |

100.00 |

| Widower/widow |

4 |

56.87 |

24.91 |

12.4 |

17.22 |

96.53 |

34.38 |

92.50 |

| |

F=10.785; p=0.001 |

| Number of children |

None |

120 |

86.76 |

13.36 |

1.22 |

84.35 |

89.18 |

38.75 |

100.00 |

| One |

84 |

79.65 |

17.94 |

1.95 |

75.76 |

83.55 |

33.75 |

100.00 |

| Two |

129 |

74.74 |

18.61 |

1.63 |

71.49 |

77.98 |

27.50 |

100.00 |

| Three |

20 |

74.44 |

18.79 |

4.20 |

65.64 |

83.23 |

42.50 |

96.25 |

| |

F=11.382; p=0.001 |

| Education |

Three years of high school |

103 |

78.99 |

17.57 |

1.73 |

75.55 |

82.42 |

33.75 |

100.00 |

| Four years of high school |

193 |

79.80 |

17.80 |

1.28 |

77.27 |

82.32 |

33.75 |

100.00 |

| High school – two and a half year studies |

16 |

72.85 |

19.72 |

4.93 |

62.34 |

83.36 |

27.50 |

97.50 |

| High school - three-year vocational or academic studies |

14 |

84.15 |

18.12 |

4.84 |

73.68 |

94.61 |

48.75 |

100.00 |

| |

F=2.076; p=0.083 |

Work in shifts

Work hours

Workplace |

Yes |

288 |

78.72 |

18.26 |

1.07 |

76.60 |

80.84 |

27.50 |

100.00 |

| No |

65 |

85.54 |

12.82 |

1.59 |

82.37 |

88.72 |

55.00 |

100.00 |

| F=8.157; p=0.005 |

| Up to 8 hours |

36 |

84.96 |

13.39 |

2.23 |

80.43 |

89.50 |

55.63 |

97.50 |

| 8 to 12 hours |

277 |

79.71 |

17.68 |

1.06 |

77.61 |

81.80 |

27.50 |

100.00 |

| More than 12 hours |

40 |

77.37 |

19.56 |

3.09 |

71.11 |

83.63 |

33.75 |

100.00 |

| F=1.931; p=0.147 |

| Boss of security service |

53 |

85.81 |

12.79 |

1.75 |

82.28 |

89.34 |

54.38 |

100.00 |

| Security officer |

300 |

78.95 |

18.11 |

1.02 |

76.89 |

81.00 |

27.50 |

100.00 |

| |

F=6.986; p=0.009 |

Table 4.

Composite MHC score in relation to socio-descriptive characteristics of employees.

Table 4.

Composite MHC score in relation to socio-descriptive characteristics of employees.

| Characteristics |

N |

|

SD |

SEM |

95% CI |

Min |

Max |

| Lower |

Upper |

| Sex |

Мale |

330 |

77.00 |

13.00 |

0.71 |

75.59 |

78.41 |

30.38 |

100.00 |

| Female |

23 |

82.11 |

14.41 |

3.00 |

75.88 |

88.35 |

48.71 |

100.00 |

| |

F=3.275; p=0.071 |

| Marital status |

Married |

227 |

76.53 |

12.22 |

.81 |

74.93 |

78.13 |

30.38 |

100.00 |

| Unmarried |

87 |

80.99 |

13.77 |

1.47 |

78.05 |

83.93 |

33.75 |

100.00 |

| Extramarital union |

12 |

76.85 |

18.13 |

5.23 |

65.32 |

88.37 |

37.00 |

95.25 |

| Divorced |

23 |

75.42 |

12.78 |

2.66 |

69.89 |

80.95 |

39.46 |

95.50 |

| Widower/widow |

4 |

55.63 |

8.10 |

4.05 |

42.73 |

68.53 |

48.71 |

66.50 |

| |

F=4.961; p=0.001 |

| Number of children |

None |

120 |

79.55 |

13.49 |

1.23 |

77.11 |

81.99 |

33.75 |

100.00 |

| One |

84 |

78.06 |

13.99 |

1.52 |

75.03 |

81.10 |

39.46 |

100.00 |

| Two |

129 |

75.17 |

12.48 |

1.09 |

72.99 |

77.34 |

30.38 |

100.00 |

| Three |

20 |

74.93 |

9.06 |

2.02 |

70.69 |

79.17 |

56.33 |

91.00 |

| |

F=2.653; p=0.049 |

| Education |

Three years of high school |

103 |

103 |

77.18 |

12.8 |

1.26 |

74.68 |

79.690 |

40.13 |

| Four years of high school |

193 |

193 |

76.99 |

13.4 |

.96 |

75.09 |

78.903 |

30.38 |

| High school – two and a half year studies |

16 |

16 |

74.96 |

14.7 |

3.69 |

67.07 |

82.850 |

37.00 |

| High school - three-year vocational or academic studies |

14 |

14 |

81.19 |

13.7 |

3.67 |

73.26 |

89.129 |

48.42 |

| |

F=0.692; p=0.598 |

| Work in shifts |

Yes |

288 |

76.73 |

13.45 |

.79 |

75.17 |

78.29 |

30.38 |

100.00 |

| No |

65 |

80.00 |

11.36 |

1.40 |

77.19 |

82.82 |

53.75 |

100.00 |

| |

F=3.305; p=0.070 |

| Work hours |

Up to 8 hours |

36 |

79.14 |

11.14 |

1.85 |

75.37 |

82.91 |

53.75 |

96.50 |

| 8 to 12 hours |

277 |

77.60 |

12.83 |

.77 |

76.08 |

79.11 |

30.38 |

100.00 |

| More than 12 hours |

40 |

73.89 |

16.29 |

2.57 |

68.68 |

79.11 |

39.46 |

96.75 |

| |

F=1.773; p=0.171 |

| Workplace |

Boss of security service |

53 |

78.88 |

12.25 |

1.68 |

75.50 |

82.25 |

50.88 |

100.00 |

| Security officer |

300 |

77.06 |

13.29 |

.76 |

75.55 |

78.57 |

30.38 |

100.00 |

| |

F=0.857; p=0.355 |

Table 5.

TQL scores in relation total socio-descriptive characteristics for employees.

Table 5.

TQL scores in relation total socio-descriptive characteristics for employees.

| Characteristicstics

|

N |

|

SD |

SEM |

95% CI |

Min |

Max |

| Lower |

Upper |

| Sex |

Male |

330 |

78.17 |

13.78 |

0.75 |

76.68 |

79.67 |

33.63 |

100.00 |

| Female |

23 |

85.55 |

11.90 |

2.48 |

80.41 |

90.70 |

49.04 |

100.00 |

| |

F=6.260; p=0.013 |

| Age |

Male |

330 |

44.09 |

11.44 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Female |

23 |

36.91 |

7.92 |

|

|

|

|

|

| F=8.752; p=0.003 |

| |

Married |

227 |

76.63 |

13.64 |

.90 |

74.84 |

78.41 |

33.63 |

100.00 |

| Unmarried |

87 |

84.61 |

12.25 |

1.31 |

82.00 |

87.22 |

36.25 |

100.00 |

| Extramarital union |

12 |

84.02 |

13.01 |

3.75 |

75.75 |

92.29 |

56.00 |

97.00 |

| Divorced |

23 |

77.23 |

11.48 |

2.39 |

72.26 |

82.20 |

54.42 |

95.25 |

| Widower/widow |

4 |

56.25 |

14.10 |

7.05 |

33.80 |

78.70 |

42.31 |

74.79 |

| |

F=9.248; p=0.001 |

| Number of children |

None |

120 |

83.16 |

11.94 |

1.09 |

81.00 |

85.32 |

36.25 |

100.00 |

| One |

84 |

78.86 |

14.67 |

1.60 |

75.67 |

82.04 |

36.69 |

100.00 |

| Two |

129 |

74.95 |

13.93 |

1.22 |

72.52 |

77.38 |

33.63 |

100.00 |

| Three |

20 |

74.68 |

11.61 |

2.59 |

69.25 |

80.12 |

52.02 |

93.63 |

| |

|

| Education |

Three years of high school |

103 |

78.09 |

13.77 |

1.35 |

75.39 |

80.78 |

36.94 |

100.00 |

| Four years of high school |

193 |

78.39 |

13.94 |

1.00 |

76.41 |

80.37 |

33.63 |

100.00 |

| High school – two and a half year studies |

16 |

73.90 |

15.14 |

3.78 |

65.84 |

81.97 |

41.71 |

97.13 |

| High school - three-year vocational or academic studies |

14 |

82.67 |

15.52 |

4.14 |

73.71 |

91.63 |

48.58 |

97.75 |

| |

|

| Work in shifts |

Yes |

288 |

77.73 |

14.32 |

.84 |

76.06 |

79.39 |

33.63 |

100.00 |

| No |

65 |

82.77 |

10.11 |

1.25 |

80.27 |

85.28 |

56.46 |

100.00 |

| |

F=7.247; p=0.007 |

| Work hours |

Up to 8 hours |

36 |

82.05 |

10.06 |

1.67 |

78.64 |

85.46 |

64.38 |

97.00 |

| 8 to 12 hours |

277 |

78.65 |

13.75 |

.82 |

77.02 |

80.28 |

33.63 |

100.00 |

| More than 12 hours |

40 |

75.63 |

16.18 |

2.55 |

70.46 |

80.81 |

36.69 |

97.63 |

| |

F=2.069; p=0.128 |

| Workplace |

Boss of security service |

53 |

12.00 |

10.09 |

1.38 |

79.56 |

85.12 |

57.90 |

100.00 |

| Security officer |

300 |

78.00 |

14.24 |

.82 |

76.39 |

79.62 |

33.63 |

100.00 |

| |

F=4.513; p=0.034 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).