1. Introduction

The mining sector has been playing an important role in Canada’s economy. The mining industry contributed 5% of Canada’s nominal GDP in 2019 [

1]. The mining sector also supports massive amounts of local employment, especially for indigenous peoples in Canada [

1]. In addition, the mining-related employment can further transfer the benefits of resource development to the local economy [

2]. However, the sustainable development of mining operations has been one of the most urgent challenges facing Canada. Mining could cause a series of environmental issues (e.g., disturbed lands, contamination of soil and water resources, and loss of biodiversity) [

3]. The mine impacted land cover and land use change would also affect the carbon sink, aggravating global warming and local climate risks [

3,

4]. Thus, one of the most important practices for the sustainable development of mining operations is to restore the vegetation, soils, biodiversity, and ecological processes of the disturbed lands at post-closure mine sites. Rehabilitation and revegetation can offer physical, chemical and biological benefits on reclaimed mine sites, e.g. [

5,

6,

7]. In addition, the reclaimed mining sites can recover their ability to store carbon and nitrogen [

8].

In Canada, prior to the legislation mandating planning for closure and the posting of assurance, many of mine sites had typically undergone reclamation through natural succession following disturbance, which is known as spontaneous revegetation or passive reclamation [

9,

10,

11]. The other method is active reclamation in which land reclamation projects are planned and implemented to restore the areas of interest to a specified level of ecosystem function and improve the integrity of the regional ecosystem and social-ecological resilience [

12]. The passive reclamation can increase biodiversity and ecological functions at relatively low financial expenses, but typically resulted in the slower recovery and less control over the ecosystem properties than the active reclamation [

10,

13]. In contrast, active reclamation and revegetation can facilitate and accelerate landscape and ecosystem recovery [

14].

A long-term monitoring of land cover change is an important element of sustainable reclamation practices pertaining to disturbance from mining operations [

3]. Remote sensing techniques can be used to evaluate the extent of mine site revegetation, offering an important opportunity to better understand mine site reclamation behaviour and its impacts on sustainable development [

15]. Relative to the ground-based field survey, remote sensing offers its advantages (e.g., better spatial coverage, less labor and financial expenses) in monitoring land cover change. Remote sensing methods have been increasingly used for detecting mine site rehabilitation and revegetation in Canada over the past decades, e.g. [

13,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. In many of these studies, the multi-temporal multispectral, e.g. [

13,

16,

19,

20,

21] or hyperspectral, e.g. [

17,

18] imagery data were used to derive the vegetation indices and/or the classified land cover types, which were then utilized to track the mine site revegetation.

However, although significant progress has been made in remote sensing-based assessment of mine site revegetation and ecological restoration in Canada, most of the evaluations focused on only the reclamation and revegetation behavior at a single mine site. As such, there is currently a lack of information on how different the landscape recovery behaved at different reclaimed mine sites in Canada. To this end, the present study uses remote sensing techniques to examine vegetation cover change over space and time at multiple rehabilitated mine sites across Canada. The inter-comparison of multiple mine sites would advance the understanding of mine site reclamation behavior and the relevant sustainable practices in Canada.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mining Sites

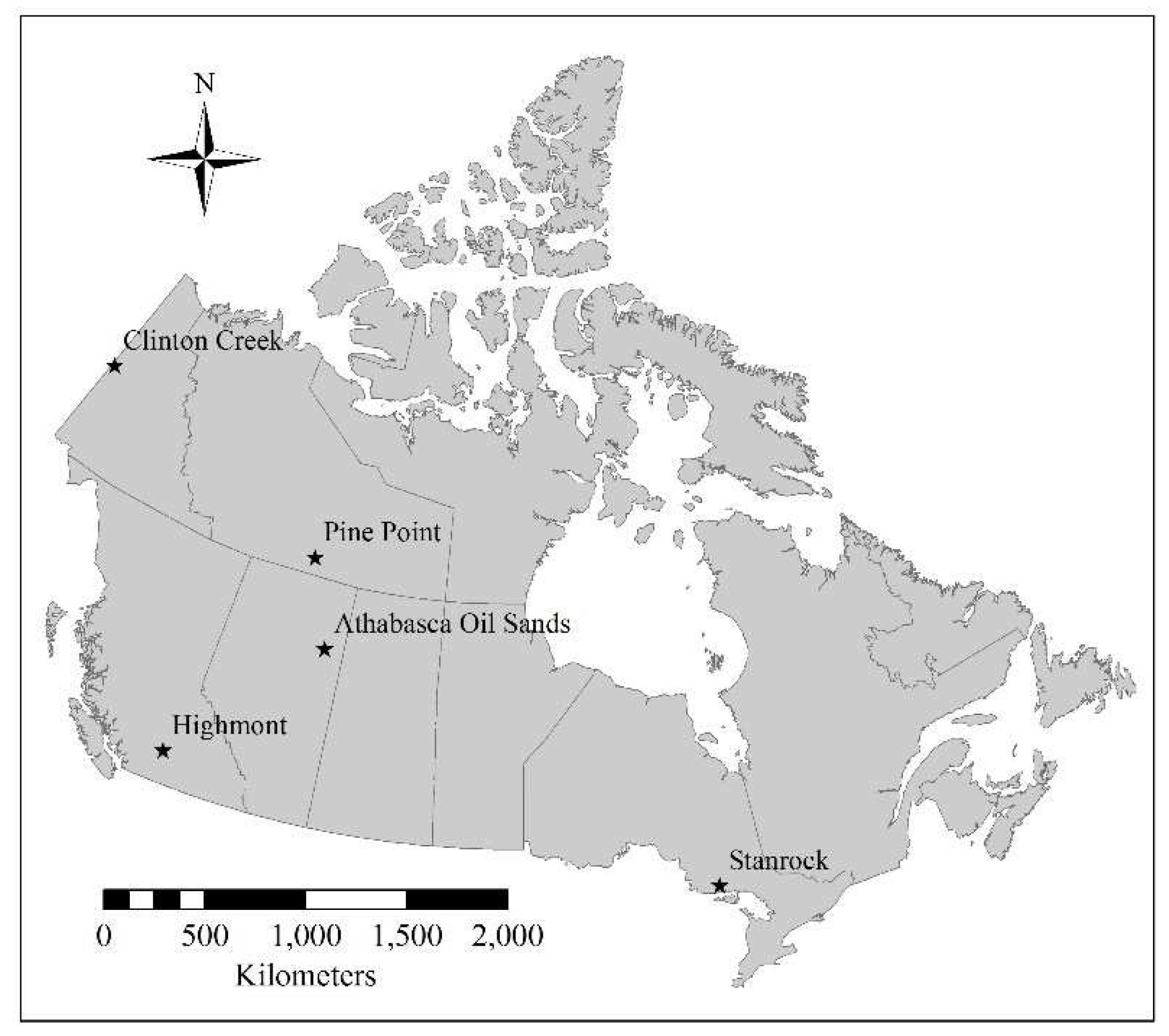

The present study is designed to compare the performance of reclaimed mine sites in Canada. The following representative post-closure mine sites are selected for the evaluation: Pine Point Mine in the Northwest Territories of Canada, Wapisiw Lookout and Gateway Hill at the Athabasca oil sands, Highmont in British Columbia, Stanrock in Ontario, and Clinton Creek Mine in Yukon (

Table 1). These sites are selected because they can provide a diversity of revegetation behavior and capture the key mine site reclamation and relevant sustainable practices in Canada.

The location of the selected mine sites is shown in

Figure 1 (note that both the Gateway Hill site and the Wapisiw Lookout site are located within the Athabasca oil sands, Alberta). For each selected site, the Tailings Management Areas (TMA), if existed, are primarily targeted in the present study. The mine sites are briefly described as follow.

The Pine Point Mine site was a lead-zinc open pit mine with a majority stake owned by Teck Cominco Metals Ltd. The mining operations started in 1964 and ceased in 1988 [

23]. Throughout the life of mine operations, approximately 70 million tons of ore were extracted at the site. The TMA was roughly 700 ha, containing approximately 54 million tonnes of tailings. An abandonment and restoration plan was implemented upon closure of the mine [

23]. However, although the closure plan was updated several times, a passive reclamation has been dominating the Pine Point Mine TMA over the past decades.

Both Wapisiw Lookout and Gateway Hill are located at the Athabasca oil sands in northern Alberta. The Wapisiw Lookout tailings pond (about 220 ha) began its operations in 1967 and was decommissioned in 1997 [

3,

24]. The active reclamation efforts at the site mainly included moving the tailings from the pond to a different location for treatment, filling the pond with clean sands covered with a thick topsoil layer, and the planting of crops, grasses, and trees [

3]. The site has entered a permanent reclamation since 2010 [

24]. In contrast, Gateway Hill, covering an area of about 104 ha, was used as an overburden stockpile for mining operations (rather than a storage of tailings or other potentially contaminated materials). The overburden site ceased its mining operations in the early 1980s and was then revegetated with trees and shrubs [

24]. The Gateway Hill site received an official reclamation certificate from the Government of Alberta in 2008 [

25].

The Highmont tailings storage facility (TSF) belongs to the Highland Valley Copper (HVC) mine in south-central British Columbia. HVC is one of the world’s largest open-pit (mainly copper and molybdenum) mines. The Highmont TSF (about 220 ha) was used to manage the tailings from 1980 to 1984 [

26]. The reclamation at the HVC mine was based upon an end land use plan [

27]. Accordingly, the Highmont TSF area has been revegetated mainly through the establishment of aquatic vegetation and the wetland revegetation efforts [

27].

Stanrock, belong to Denison Mines Limited, is located in the Elliot Lake region, Ontario. The Elliot Lake area used to serve as a major base for uranium mining in Ontario [

28,

29]. The Stanrock TMA, covering an area of about 52 ha, was used for tailings deposition from two Elliot Lake mines (Stanrock and Can-Met) between the middle 1950s to the early 1960s, although the decommissioning of the uranium TMA started shortly after 1992 when the whole Denison Mines uranium mining facility in Elliot Lake permanently ceased operations [

28,

30]. Acid generation was a major environmental concern associated with the Stanrock uranium tailings. However, since the last deposition of tailings in the Stanrock TMA occurred in the early 1960s, almost no reactive pyrite remained in the surface layer of the tailings by the early 1990s when the decommissioning started [

30]. A dry-cover approach was used to decommission the Stanrock TMA [

29]. Since 1998 when most of significant capital reclamation activities in the region had been finished, the decommissioning has entered the long-term monitoring phase.

The Clinton Creek Mine was owned by the Cassiar Asbestos Corporation and operated as an asbestos mine from 1968 to 1978 [

31]. The mine site is located about 100 km northwest of Dawson City, Yukon. During its operations, asbestos ore was extracted from the open pits and transported to a mill for processing. Waste rock was dumped in several areas along the Clinton Creek channel (the Clinton Creek waste rock dumps) and the Porcupine Creek channel [

31]. The revegetation was found to be naturally occurring (i.e., passive revegetation) on the waste rock dumps since the closure of the mine in 1978 [

32]. In this study, we assess the revegetation behavior over the Clinton Creek waste rock dumps.

2.2. Remote Sensing Imagery Data

So far, the Landsat satellites have provided nearly 50 years of imagery data collection, which makes the Landsat images very suitable for the long-term monitoring of land surface change. In this study, the multi-temporal remote sensing images collected from the satellites Landsat 5 (operating from March 1984 to January 1993) and Landsat 8 (operating from February 1993 to present) are used to quantify the land cover change and extent of revegetation at the target mine sites. The Landsat 5 Thematic Mapper (TM) and Landsat 8 Operational Land Imager (OLI) images (Collection 2 Level-2 atmospherically corrected products) for each mine site, preferably from the peak growing months between the year 1984 (or the respective closure year when it is later than 1984) and the year 2021, were downloaded from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) Earth Explorer database (

https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/). The near-anniversary imagery data are used to minimize the influence of seasonal sun-angle and plant phenological differences on the land cover change detection.

A python-based batch preprocessing of the downloaded Landsat images is conducted. During the image preprocessing, the ArcPy Python site package and the composite bands management tool are used to create the composite images (by stacking the image bands). The composite images are then clipped to their respective mine site area of interest within the ArcGIS Pro model builder.

2.3. Analysis Method

Firstly, the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) analysis is performed. The NDVI is a quantitative measure of vegetation abundance and vigor. At each image pixel, the NDVI is calculated as follows [

33].

where B

nir and B

red denote the reflectance values (i.e., Landsat Collection 2 surface reflectance for this study) from the near-infrared and red spectral bands, respectively. The NDVI ranges from -1 to 1. A higher NDVI indicates more live green vegetation. For each mine site, the temporal (i.e., interannual) variations of area-averaged NDVI values are derived from the Landsat images. A linear regression based upon the Least Squares method is then applied to quantify the vegetation cover change trend over time.

Secondly, the images are classified into different land cover categories using the random forest method [

34]. Given a classification year, the Landsat surface reflectance images from June to September of the year were used for producing the classification map based on the median synthesis method. Further, a post-classification change detection was performed to monitor land use/cover change over the study sites.

Thirdly, the Regrowth Index (RI) is calculated at each study location. The RI is a measure of the extent of vegetation recovery resulting from reclamation at a disturbed site relative to an undisturbed reference site [

20]. Here, the RI is calculated as the NDVI difference between a disturbed mine site (NDVI

disturbed) and the corresponding undisturbed reference site (NDVI

reference ):

At each study location, the area without visually noticeable anthropogenic disturbances is selected as the corresponding reference site. The use of reference sites is crucial for the monitoring of reclamation success level [

12,

20,

35].

3. Results

3.1. NDVI Analysis

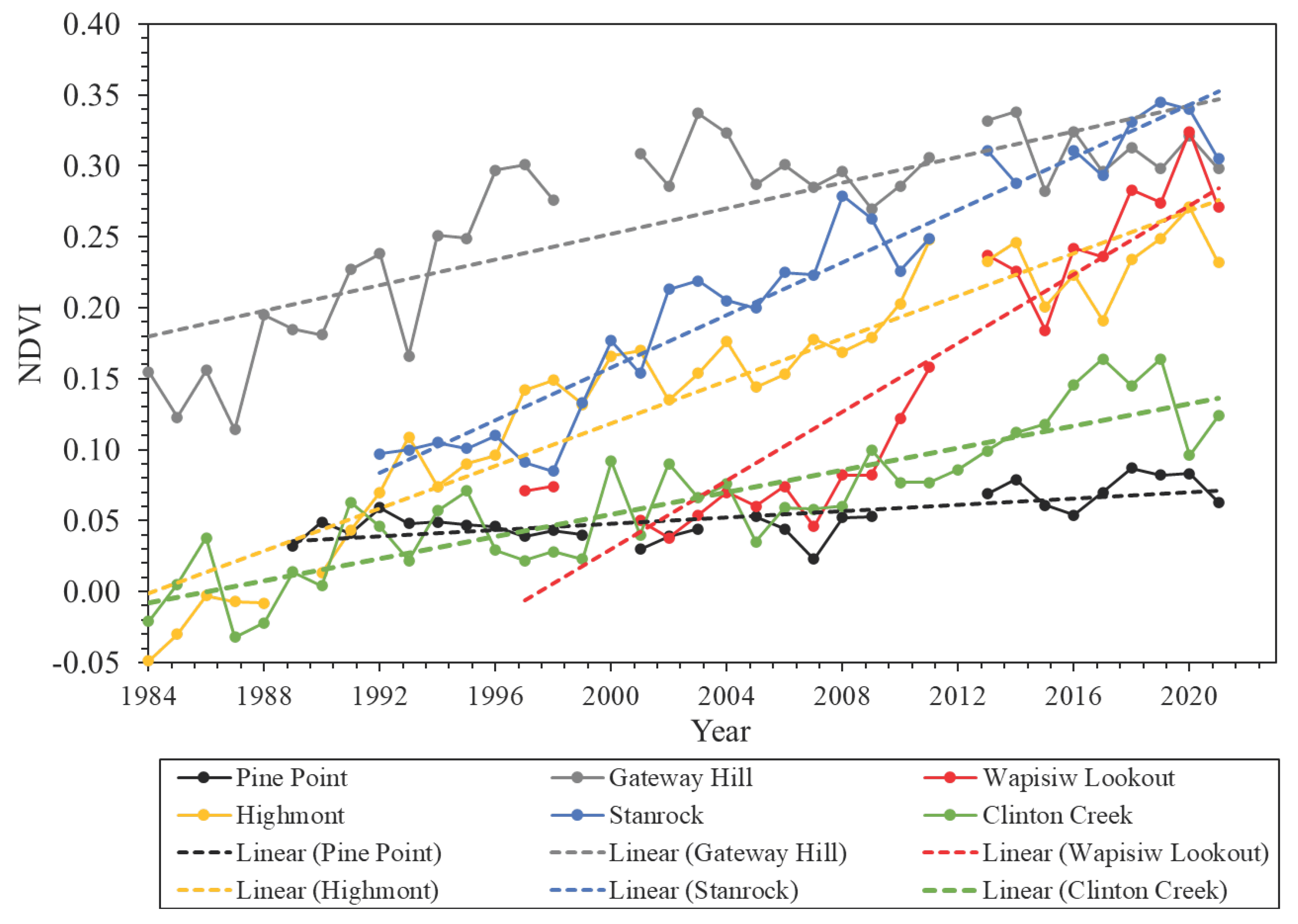

Figure 2 shows the NDVI changes for the five mine sites from their respective closure years to the present (year 2021). The corresponding linear regression slopes (i.e., annual change rate in NDVI) are provided in

Table 2. Note that the NDVI is not computed when the corresponding cloud-free Landsat imagery is not available. Clearly, all mine sites show increasing NDVI trends, but with different change rates (

Figure 2 and

Table 2).

The Wapisiw Lookout TMA site was closed later than other mine sites but showed the largest increasing trend in NDVI (

Table 2). Note that although the Wapisiw Lookout TMA became inactive in 1997, the significant reclamation and planting efforts officially started between 2009-2010 [

24]. Accordingly, starting from 2009, the NDVI of the site has increased rapidly (

Figure 2, red). The NDVI of Stanrock has the second highest growing rate with the speedy NDVI increase starting in 1998-1999 when the significant capital reclamation activities in the region had already completed (

Figure 2, blue).

The Highmont and Gateway Hill were closed in the early 1980s, earlier than other sites. Although the Highmont site had the lowest NDVI (across the five sites) prior to the reclamation, a monotonic and substantial NDVI increasing trend has been detected for the site (

Figure 2, yellow and

Table 1). This may be attributed to the implementation of an efficient end land use plan at the site [

27]. In contrast, the Gateway Hill site had the highest pre-revegetation NDVI across the five study sites. This is not surprising since unlike other sites, Gateway Hill was used as an overburden stockpile for mining operations rather than a storage of tailings. The NDVI of reclaimed Gateway Hill showed a strong upwards trend up to 2003 and then has remained relatively steady (

Figure 2, gray).

The Pine Point TMA and the waste rock dumps of the Clinton Creek mine collectively showed the smallest change in NDVI over time. This is consistent with the findings in [

13,

32] and reflects the behavior of passive revegetation. However, note that the slow NDVI increasing is still statistically significant (p< 0.001).

3.2. Image Classification and Post-Classification Change Detection

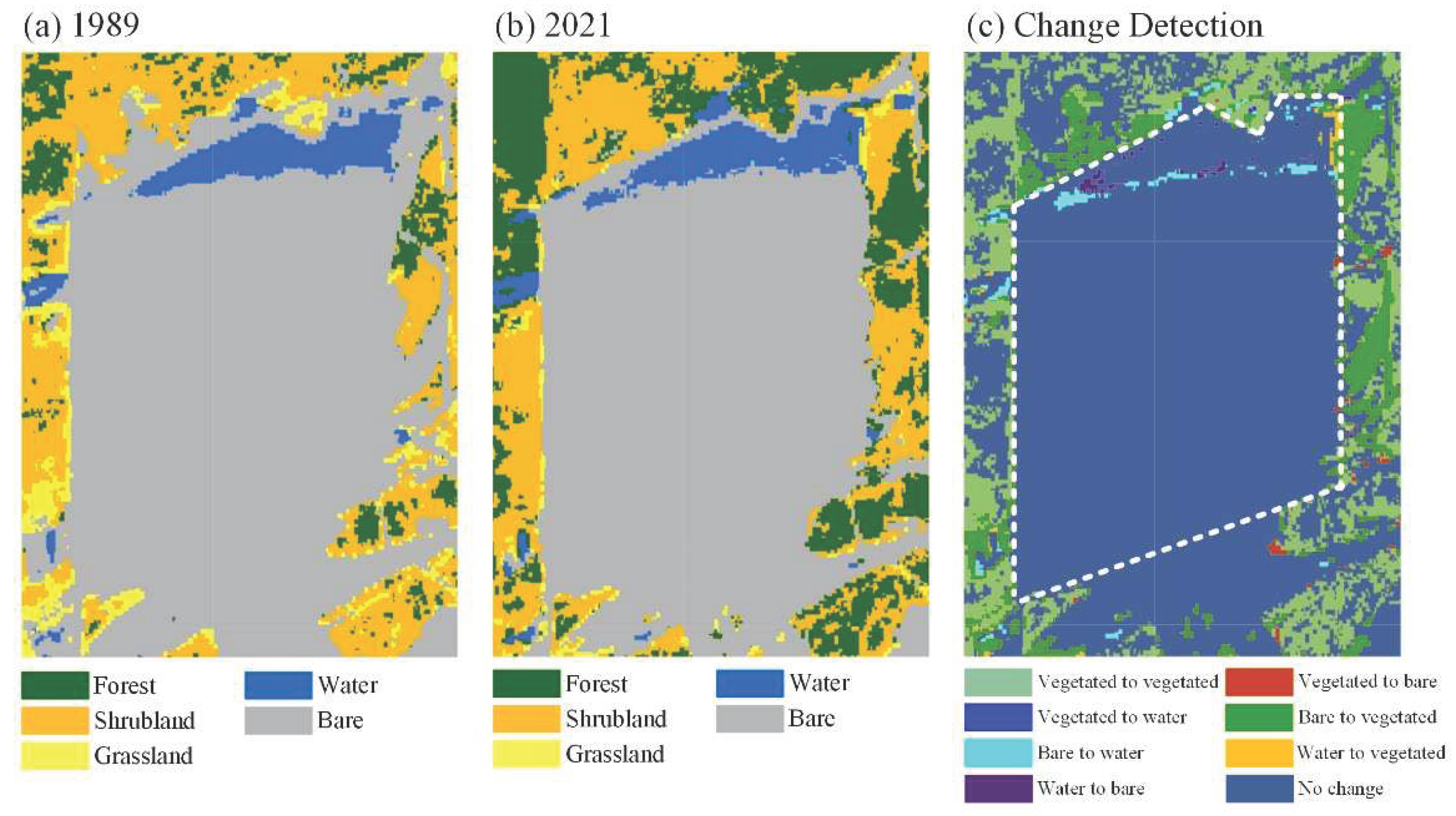

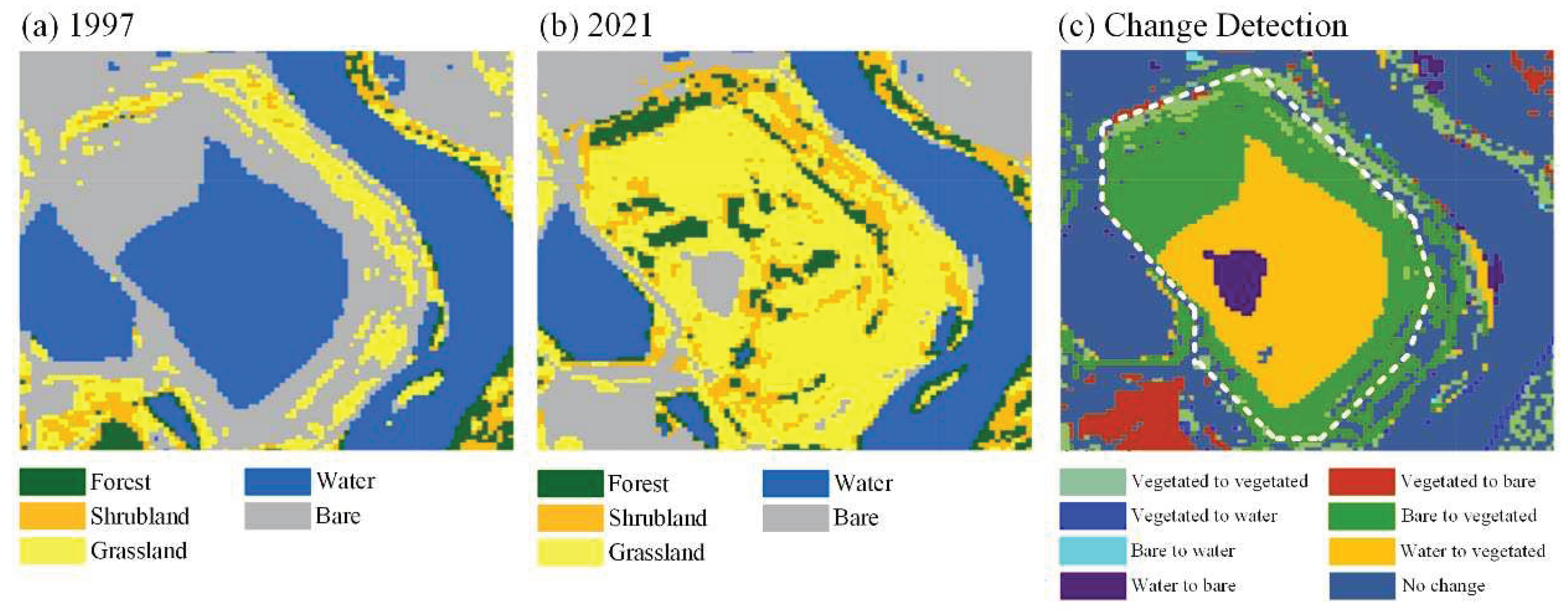

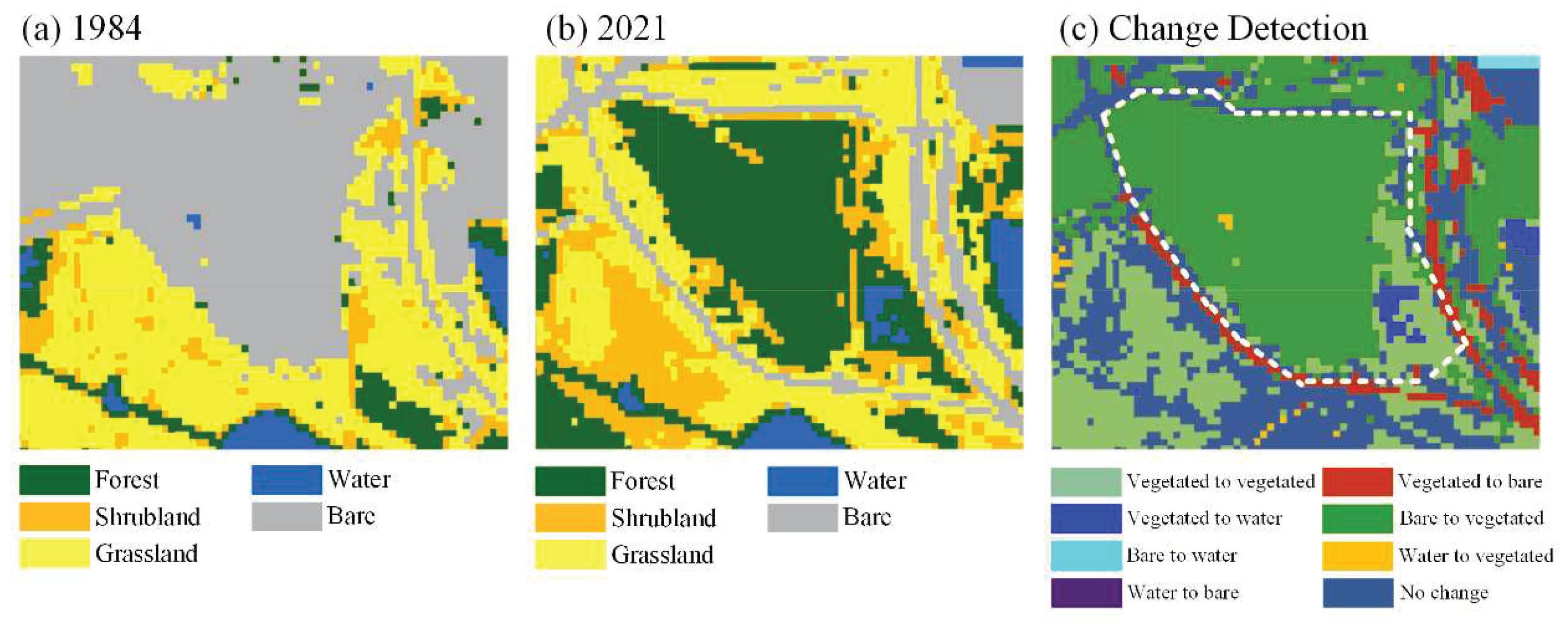

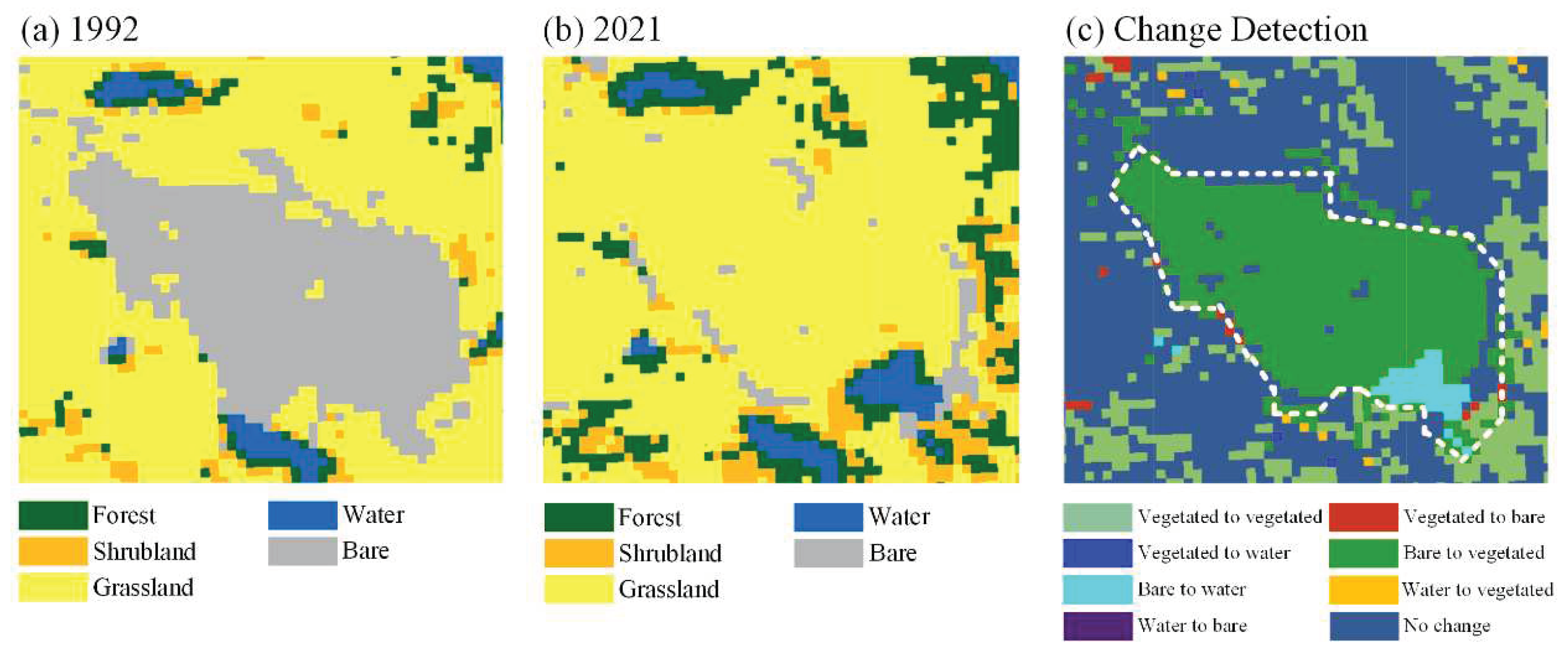

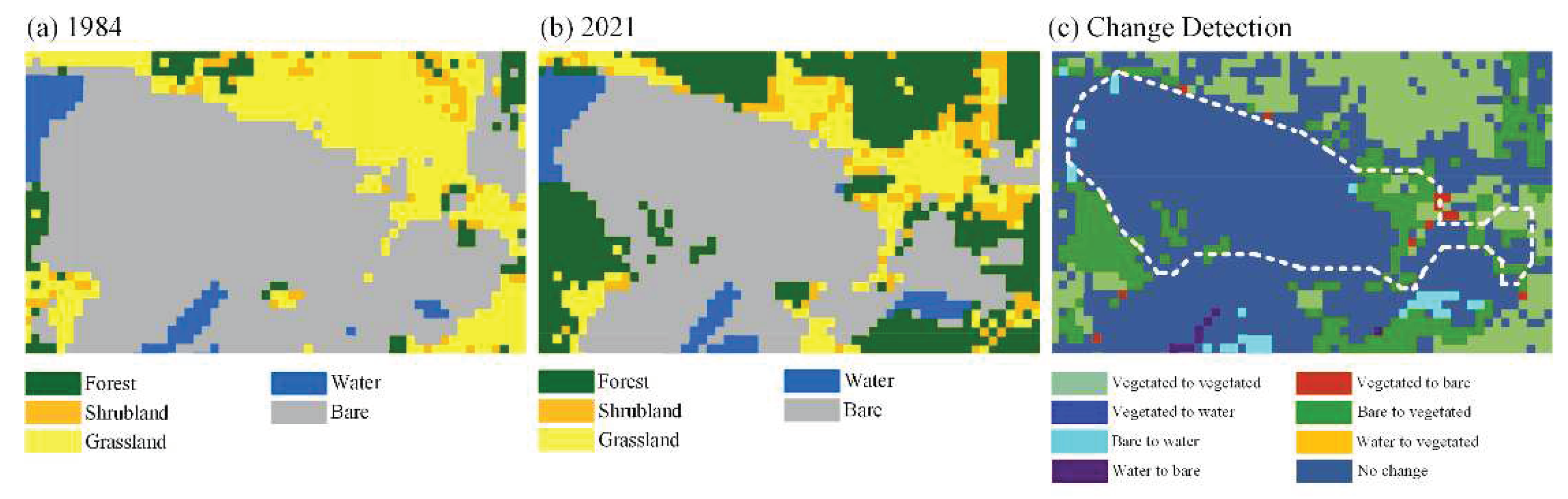

Figures 3 to 8 provide the land cover classification and post-classification change detection results over the 6 study sites, respectively. The images from the year 1984 (or their respective closure year when it is later than 1984) and the present (year 2021) are classified into five land cover categories: forest, shrubland, grassland, water surface, and bare land (including bare soil/rock, road, building, etc.).

Until the present, there is a lack of considerable vegetation cover over the main body of the Pine Point TMA (

Figure 3b). Over the past decades, only limited patches of revegetation appeared on the periphery of the TMA (

Figure 3c). This is consistent with the passive revegetation behavior [

13,

36,

37], where early plant colonization mainly occurred at the perimeter and stems from existing vegetation. In addition, the marginal increase in the vegetated area is consistent with the small NDVI change quantified for the site (

Figure 2, black).

The Wapisiw Lookout TMA at its closure was dominated by water surface (tailings pond) and bare soil or rock with limited vegetation cover only along the perimeter of the TMA (

Figure 4a), while the vegetation covering is dominant at the contemporary site (

Figure 4b). The land cover change clearly reveals the substantial extent of the revegetation over the Wapisiw Lookout TMA (

Figure 4c).

A large patch of bare land was evident for the Gateway Hill site at its closure (

Figure 5a). The bare land has largely turned into vegetated area through the site reclamation activities (

Figure 5b and 5c). Except for the considerable increase in vegetated area, the new road network (triangle-shaped bare covering in

Figure 5b and red patches in

Figure 5c) has also been developed for the reclaimed Gateway Hill.

The main body of the Highmont TMA was dominated by water surface (tailings pond) and bare soil or rock when the site was closed in 1984 (

Figure 6a), which led to the near-zero NDVI for the site at its closure (

Figure 2, yellow). The major portion of the tailing pond and bare land have been revegetated by 2021 (

Figure 6b), although vegetation cover is still absent at the central portion of original tailings pond and along the boundary of the TMA (

Figure 6b).

At the Stanrock TMA, the bare land (rather than tailing pond water surface) had been dominant by 1992 (

Figure 7a) since the last deposition of tailings at the site happened in the early 1960s [

30]. The post-classification change detection indicates that the Stanrock TMA had experienced a substantial revegetation over the past 30 years (

Figure 7c). The bare land has largely turned into vegetated covering through the reclamation activities (

Figure 7c). However, the small bare and water surface (tailing) fragments still exist at the present site (

Figure 7b). This may be partially due to the existence of infrastructure (i.e., spillways) for the surface drainage from the acid generating tailings [

30].

Figure 8 clearly shows the revegetation that naturally occurred over the Clinton Creek waste rock dumps. The naturally occurring revegetation appears only on a small portion of the dumps. Most of the dump slopes still lack vegetation cover by 2021.

3.3. Regrowth Index Analysis

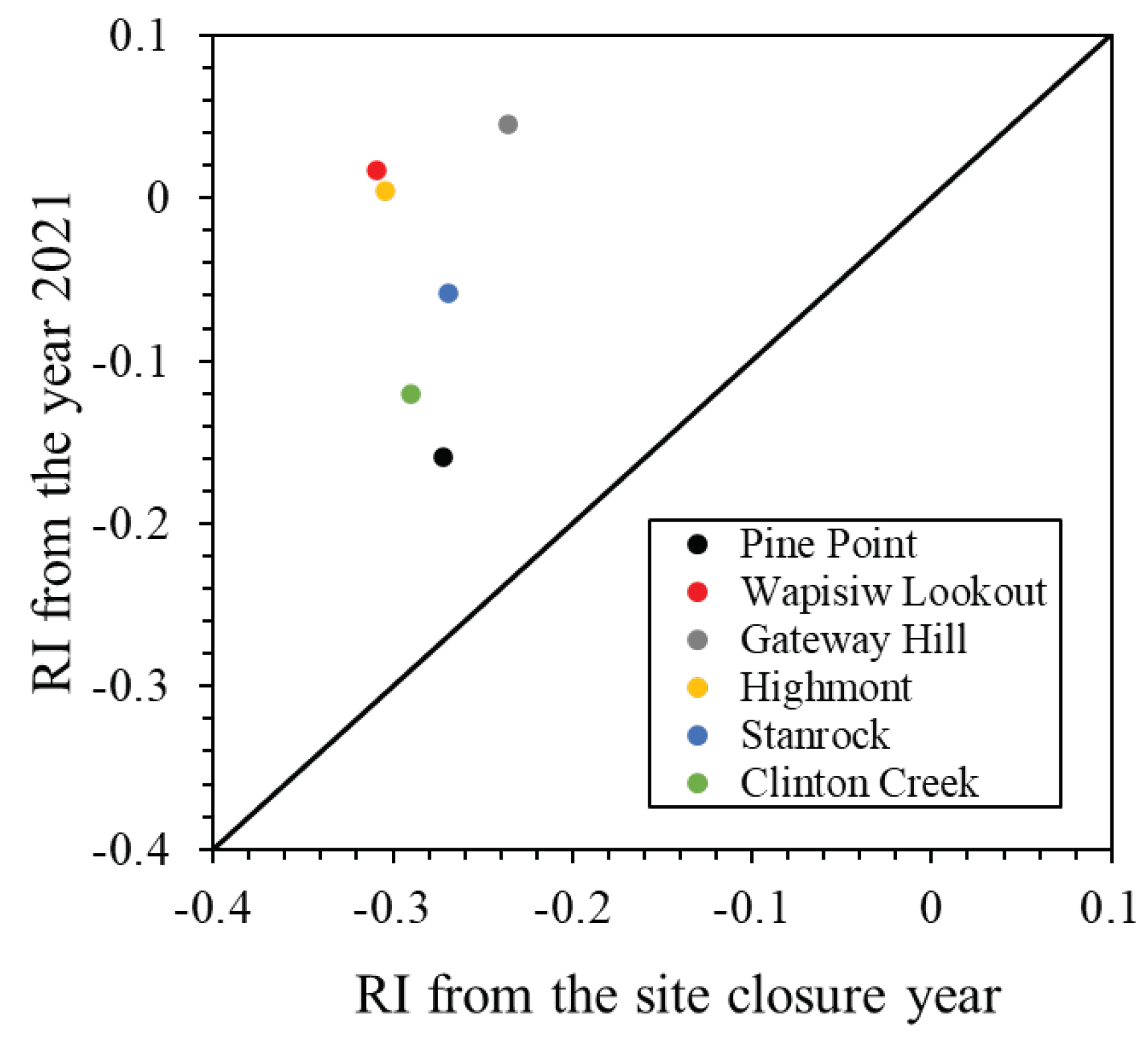

As stated earlier, the use of RI can help estimate the level of revegetation success. In this study, the RI values from the site closure year and year 2021 are calculated and compared across the five mine sites, as shown in

Figure 9.

The RI values from the respective closure years of the six mine sites are all below zero (around -0.31 to -0.23) (

Figure 9). RI is defined as the NDVI departure of the mine site from the corresponding undisturbed reference site (Equation 2). Thus, the negative RI indicates that the disturbances existed for each site at its closure. A more negative RI means a higher degree of disturbance relative to the respective undisturbed reference site. As shown in

Figure 9, the differences in the initial (site closure) RI value across the five sites are small (all falling within around -0.31 to -0.23) except that the overburden site Gateway Hill showed a slightly lower distribute level (i.e., a slightly less negative RI) than other sites (open tailings areas). The revegetation procedure, if occurs, is expected to alleviate the disturbances and therefore raise the RI values. Accordingly, by 2021, all study sites had experienced an increase in RI with the largest (lowest) RI increase for Gateway Hill (Pine Point).

The RI values are close to or slightly above zero for the present Gateway Hill, Wapisiw Lookout, and Highmont sites (

Figure 9). This indicates that the vegetation covering conditions of the three sites have already been restored to a level that is very close to or better than the undisturbed or pre-mining situation. For the reclaimed Stanrock site, although a substantial increase in RI is also observed, the latest RI value is still negative (about -0.06), which reflects the remaining disturbance, e.g., the observed fragments of water surface and bare land at the site (

Figure 7b). Unsurprisingly, the present RI is still quite negative (about -0.16 to -0.12) at the passively revegetated sites (Pine Point and Clinton Creek), which collectively experienced the smallest RI increase.

4. Discussion

The sustainability of mining operations plays an important role in achieving global sustainable development goals. To advance the understanding of the sustainable practices relevant to mine site reclamation in Canada, this study assessed the land cover change over space and time at multiple rehabilitated mine sites across Canada based upon the multi-temporal Landsat images. The NDVI is a critical remote sensing index for effectively monitoring the mine site revegetation behavior. According to the NDVI analysis, an actively revegetated site (e.g., Wapisiw Lookout, Gateway Hill, Stanrock, or Highmont) had typically experienced a considerable increase in healthy vegetation covering thanks to the well-designed sustainable practices, such as the technical remediation of contaminants, adding of topsoil, application of biosolids, and reseeding with various tailored plant species, e.g. [

3]. In contrast, a slow recovery of vegetation health and abundance is most likely to occur at a post-closure mine site without experiencing significant active revegetation efforts, e.g. [

10,

32,

36,

37]. This is consistent with a weak increasing NDVI trend quantified for the Pine Point TMA, which did not undergo significant active revegetation efforts and was only capped with a thin sand and gravel mix for dust prevention. The remaining high concentration of metal contaminants at the TMA could result in phytotoxicity, nutrient deficiencies, and poor soil texture, which did not favor the establishment of vegetation [

13]. Similar results were observed for the passively revegetated Clinton Creek Mine in Yukon [

32] and the lead and zinc mine sites in China [

36].

The satellite image classification-derived change detection is also an important approach for evaluating the mine site revegetation. The resulting classification and change-detection maps further substantiated the vegetation cover change derived from the NDVI analysis. The classification results are also able to provide insights into the level of rebuilt vegetation for each reclaimed site. For example, the classification analysis indicates that the Wapisiw Lookout TMA and Gateway Hill have reached or approached their respective revegetation capacity (Figures 4b and 5b). At the present Pine Point Mine, Highmont, and Clinton Creek Mine (Figures 3b, 6b, and 8b), substantial fragments of bare land and/or water surface (tailing pond) have remained, indicating that there is space for further reestablishment of vegetations at the site.

The RI index provides a quantitative measure of the revegetation level (relative to the undisturbed or pre-mining situation) a reclaimed site has reached. A higher RI means less disturbances due to a better vegetation recovery. In this study, the RI analysis further confirms that the sustainable practices involving active revegetation can significantly improve the recovery of vegetation health and abundance at disturbed mining areas in Canada because the RI resulting from active revegetation can significantly exceed the RI experiencing only passive revegetation. The actively revegetated sites can typically be restored to a level that equals or better than the pre-mining situation (i.e., RI reaches a near-zero or above zero value). However, at a reclaimed site with acid generating tailings (e.g., at Stanrock), the soil acidity, which can increase the mobility and bioavailability of heavy metals and thus the phytotoxicity, e.g. [

38], may slow down the recovery of the site to its pre-mining state.

Clearly, this study confirms that active reclamation and revegetation is a critically important sustainable practice in closing a mine. The passive reclamation alone typically cannot provide sufficient land cover change rates and revegetation extent at contaminated sites in Canada. The quantified mine site reclamation behavior and the relevant sustainable practices would provide important guidance for evidence-based sustainable resource management in Canada and around the world.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.G. and X.X.; methodology, S.G., Y.W. and X.X.; software, S.G. and Y.W.; formal analysis, S.G., Y.W. and X.X.; data curation, S.G. and Y.W.; writing—original draft preparation, S.G.; writing—review and editing, X.X.; supervision, X.X.; project administration, X.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- The Mining Associate of Canada. Facts and Figures 2020. Available online: https://mining.ca/resources/reports/facts-and-figures-2020 (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Holcombe, S.; Kemp, D. (2020). From pay-out to participation: Indigenous mining employment as local development? Sustainable Development 2020, 28, 1122–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolan, N.S.; Kirkham, M. B.; Ok, Y.S. Spoil to soil: Mine site rehabilitation and revegetation. CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 1–371. [Google Scholar]

- Rooney, R.C.; Bayley, S.E.; Schindler, D.W. Oil sands mining and reclamation cause massive loss of peatland and stored carbon. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109, 4933–4937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Wu, P.; Wu, Y. Effect of different direct revegetation strategies on the mobility of heavy metals in artificial zinc smelting waste slag: Implications for phytoremediation. Chemosphere 2022, 286, 131678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthusaravanan, S.; Sivarajasekar, N.; Vivek, J.S.; Paramasivan, T.; Naushad, M.; Prakashmaran, J.; Gayathri, V.; Al-Duaij, O.K. Phytoremediation of heavy metals: Mechanisms, methods and enhancements. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2018, 16, 1339–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, V.; Daverey, A. Phytoremediation: A multidisciplinary approach to clean up heavy metal contaminated soil. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2020, 18, 100774. [Google Scholar]

- Ahirwal, J.; Maiti, S.K. Assessment of soil carbon pool, carbon sequestration and soil CO2 flux in unreclaimed and reclaimed coal mine spoils. Environmental Earth Sciences 2018, 77, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Rogel, J.; Peñalver-Alcalá, A.; Jiménez-Cárceles, F.J.; Carmen Tercero, M.; Nazaret González-Alcaraz, M. Evidence supporting the value of spontaneous vegetation for phytomanagement of soil ecosystem functions in abandoned metal(loid) mine tailings. CATENA 2021, 201, 105191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prach, K.; Šebelíková, L.; Řehounková, K.; del Moral, R. Possibilities and limitations of passive restoration of heavily disturbed sites. Landscape Research 2020, 45, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šebelíková, L.; Řehounková, K.; Prach, K. Spontaneous revegetation vs. Forestry reclamation in post-mining sand pits. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2016, 23, 13598–13605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gann, G.D.; McDonald, T.; Walder, B.; Aronson, J.; Nelson, C.R.; Jonson, J.; Hallett, J.G.; Eisenberg, C.; Guariguata, M.R.; Liu, J.; Hua, F.; Echeverría, C.; Gonzales, E.; Shaw, N.; Decleer, K.; Dixon, K.W. International principles and standards for the practice of ecological restoration. Restoration Ecology 2019, 27, S1–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeClerc, E.; Wiersma, Y.F. Assessing post-industrial land cover change at the Pine Point Mine, NWT, Canada using multi-temporal Landsat analysis and landscape metrics. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2017, 189, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antwi, E.K.; Boakye-Danquah, J.; Asabere, S.B.; Takeuchi, K.; Wiegleb, G. Land cover transformation in two post-mining landscapes subjected to different ages of reclamation since dumping of spoils. SpringerPlus 2014, 3, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, T.T.; Bebbington, A.; Gregory, G. Assessing impacts of mining: Recent contributions from GIS and remote sensing. The Extractive Industries and Society 2019, 6, 993–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillanders, S.N.; Coops, N.C.; Wulder, M.A.; Goodwin, N.R. Application of Landsat satellite imagery to monitor land-cover changes at the Athabasca Oil Sands, Alberta, Canada. The Canadian Geographer 2008, 52, 466–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévesque, J.; Staenz, K. Monitoring mine tailings revegetation using multitemporal hyperspectral image data. Canadian Journal of Remote Sensing 2008, 34, S172–S186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staenz, K.; Neville, R.A.; Levesque, J.; Szeredi, T.; Singhroy, V.; Borstad, G.; Hauff, P. Evaluation of casi and SFSI Hyperspectral Data for Environmental and Geological Applications—Two Case Studies. Canadian Journal of Remote Sensing 2014, 25, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badreldin, N.; Sanchez-Azofeifa, A. Estimating Forest Biomass Dynamics by Integrating Multi-Temporal Landsat Satellite Images with Ground and Airborne LiDAR Data in the Coal Valley Mine, Alberta, Canada. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 2832–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guindon, B.; Lantz, N.; Shipman, T.; Chao, D.; Raymond, D. Quantification of anthropogenic and natural changes in oil sands mining infrastructure land based on RapidEye and SPOT5. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2014, 29, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chasmer, L.; Baker, T.; Carey, S.K.; Straker, J.; Strilesky, S.; Petrone, R. Monitoring ecosystem reclamation recovery using optical remote sensing: Comparison with field measurements and eddy covariance. Science of The Total Environment 2018, 642, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, P.B.; Lechner, A.M.; Phinn, S.; Erskine, P.D. Remote sensing of mine site rehabilitation for ecological outcomes: A global systematic review. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teck Cominco. Pine Point Mine: The 1991 closure and reclamation plan with 2006 update. Available online: http://registry.mvlwb.ca/Documents/MV2017L2-0007/MV2017L2-0007%20-%20Teck%20Metals%20-%201991%20Closure%20and%20Reclamation%20Plan%20with%202006%20update%20-%20Dec-2006.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Magas, A. Landscapes of avulsion: Proposed future ecologies for Canadian oil sands reclamation. Master Thesis, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada, March 27, 2020. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1993/34599. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, J.; Dyer, S.; Woynillowicz, D. Fact or fiction: Oil sands reclamation, revised ed.; The Pembina Institute, Alberta, 2008. Available online: http://epe.lac-bac.gc.ca/100/200/300/pembina_institute/fact_fiction/fact_or_fiction_report_rev_dec08.pdf.

- Witt, P.; Hamaguchi, B.A. Preparing a high elevation tailings impoundment for final closure. British Columbia Mine Reclamation Symposium, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Freberg, M.R.; Gizikoff, K.G. Development and utilization of an end land use plan for Highland Valley Copper. In Proceedings of the 23rd Annual British Columbia Mine Reclamation Symposium in Kamloops, BC, 1999.

- Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency. Decommissioning of uranium mine tailings management areas in the Elliot Lake area. Report of the Environmental Assessment Panel, June 1996. Available online: https://publications.gc.ca/site/archivee-archived.html?url=https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2017/acee-ceaa/En105-52-1996-eng.pdf.

- Nicholson, R.V.; Ludgate, I.; Clyde, E.; Venhuis, M. The successful reclamation of acid generating tailings in the Elliot Lake uranium district of Canada. The 9th International Conference on Acid Rock Drainage, Ottawa, Canada, 20 May 2012.

- Ludgate, I.R.; Counsell, H.C.; Knapp, R.; Feasby, D.G. Decommissioning of denison and Stanrock tailings management areas. Annual hydrometallurgical meeting of the Metallurgical Society of Canadian Institute of Mining, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada, 9-15 Sep 2000.

- Tetra Tech Canada Inc. 2021 Annual Report Long-Term Performance Monitoring Program: Clinton Creek Mine, Yukon. Available online: https://open.yukon.ca/information/publications/clinton-creek-mine-site-reports (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Laberge Environmental Services. Clinton Creek Mine Waste Rock Dump: Assessment of Revegetation Potential, July 2008. Available online: https://open.yukon.ca/information/publications/clinton-creek-mine-site-reports (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Jensen, J.R. Introductory digital image processing: a remote sensing perspective, 4th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2015; p. 325. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Machine Learning 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Jaen, M.C.; Aide, T.M. Restoration success: How is it being measured? Restoration Ecology 2005, 13, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, W.S.; Ye, Z.H.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Lan, C.Y.; Wong, M.H. Natural colonization of plants on five lead/zinc mine tailings in southern China. Restoration Ecology 2005, 13, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, I.; Naguit, C.; Markham, J.; Goh, T.B.; Renault, S. Natural revegetation of a boreal gold mine tailings pond. Restoration Ecology 2013, 21, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; van Zyl, D. Distinguishing reclamation, revegetation and phytoremediation, and the importance of geochemical processes in the reclamation of sulfidic mine tailings: A review. Chemosphere 2020, 252, 126446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).