Submitted:

15 June 2023

Posted:

16 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative responses

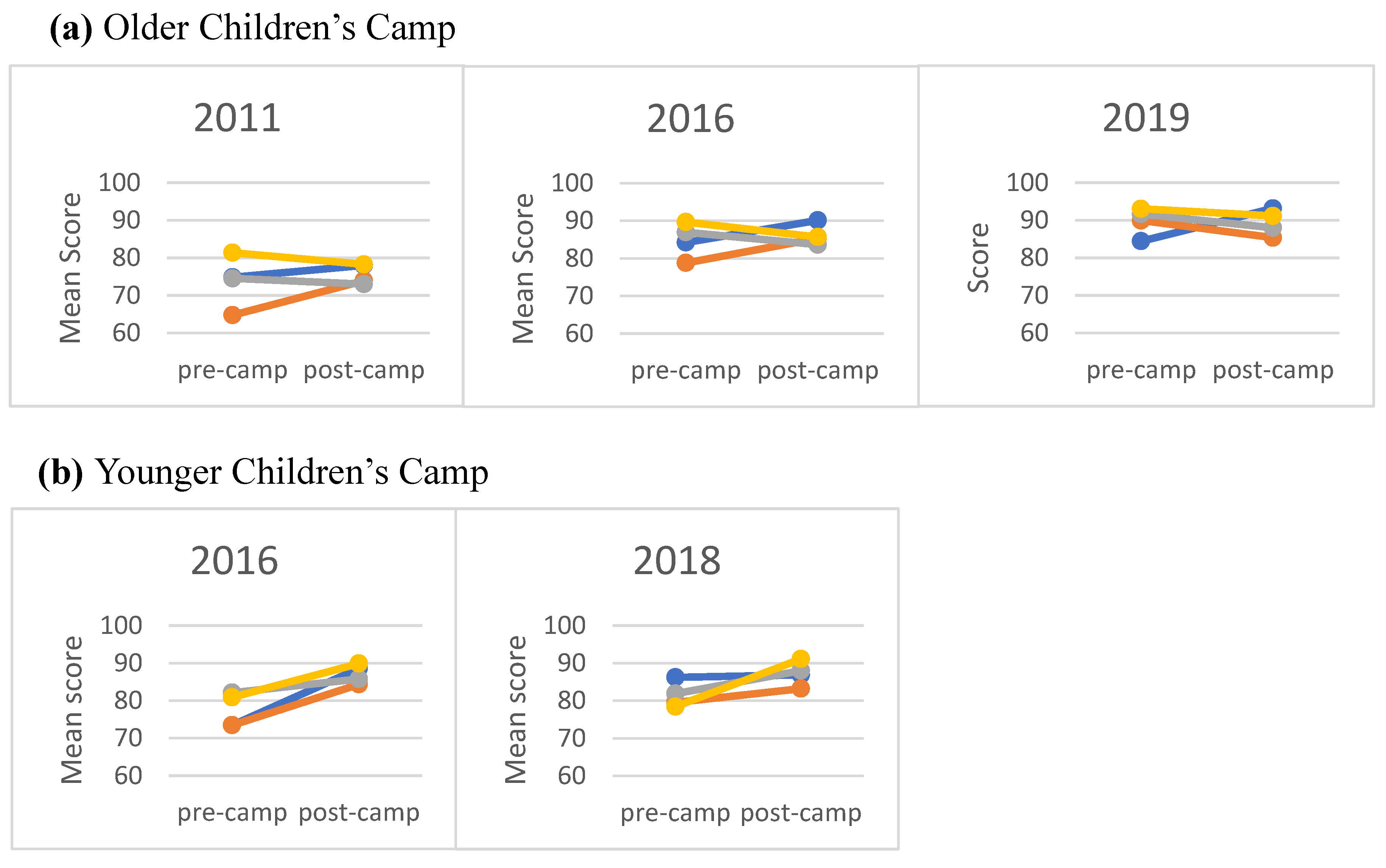

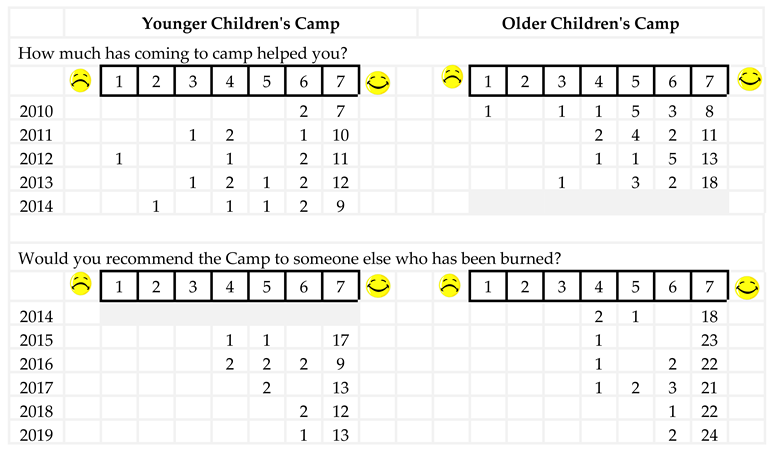

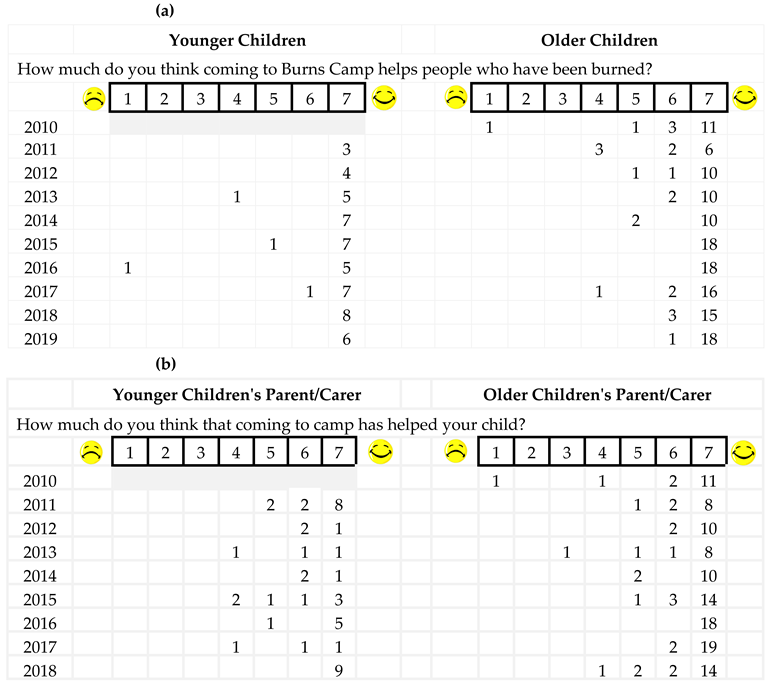

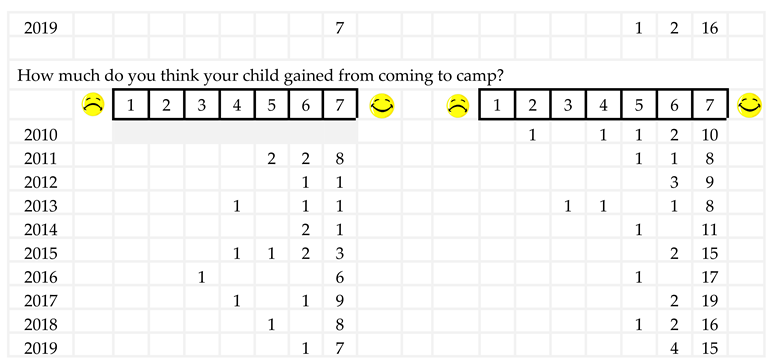

3.2. Quantitative responses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Walls Rosenstein, D.L. Camp Celebrate: A therapeutic Weekend Camping Program for Pediatric Burn Patients. J Burn Care Rehabil 1986, 7(5), 434–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doctor, M.E. Burn Camps and Community Aspects of Burn Care. J Burn Care Rehabil 1992, 13(1), 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslow, R.R.; Lobato, D. Summer Camps for Children With Burn Injuries: A Literature Review. J Burn Care Res 2010, 31(5), 740–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tropez-Arceneaux, L.L.; Castillo Alaniz, A.; Lucia Icaza, I.; Alejandra Murillo, E. The Psychological Impact of First Burn Camp in Nicaragua. J Burn Care Res. 2017, 38(1), e1–e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayun, Y.; Ben-Dror, A.; Schreuer, N.; Eshel, Y.; Ad-El D.; Olshinka, A. Camp “Sababa” (awesome) – The world of children with burns. Burns, 2022 48, 423-419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2021.04.017. [CrossRef]

- Cox, E. R.; Call, S. B.; Williams, N.R.; Reeves, P.M. Shedding the Layers: Exploring the Impact of the Burn Camp Experience on Adolescent Campers' Body Image. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2004, 25(1), 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaskell, S.L. The challenge of evaluating rehabilitative activity holidays for burn-injured children: Qualitative and quantitative outcome data from a Burns Camp over a five-year period. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 2007, 10 (2), 149-160. [CrossRef]

- Maertens, K.; Ponjaert-Kristoffersen, I. The Expectations and Experiences of Children Attending Burn Camps: A Qualitative Study. J Burn Care Res. 2008, 29(3), 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaskell, S.L.; Cooke, S.; Lunke, M.; O’Shaughnessy, J.; Kazbekov, M.; Zajicek, R. A Pan-European evaluation of residential burn camps for children and young people. Burns, 2010 36, 511-521. [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.; Peter G.M. Van der Heijden, P.G.M.; Van Son, M.J.M.; Van de Schoot, R.; Van Loey, N.E.E. Impact of pediatric burn camps on participants’ self-esteem and body image: An empirical study. Burns 2011, 37(8), 1317-1325. [CrossRef]

- Neill, J.T.; Goch, I.; Sullivan, A.; Simons, M. The role of burn camp in the recovery of young people from burn injury: A qualitative study using long-term follow-up interviews with parents and participants. Burns 2022, 48(5), 1139–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biggs, K.; Heinrich, J. J.; Jekel, J.F.; Cuono, C.B. The Burn Camp Experience: Variables That Influence the Enhancement of Self-Esteem. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1997, 18(1), 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnoldo, B.; Crump, D.; Burris, A.; Hunt, J.; Purdue, G. Self-Esteem Measurement Before and After Summer Burn Camp in Pediatric Burn Patients. J Burn Care Res. 2006, 27(6), 786–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the adolescent self-image, Princeton University Press: Princeton, United States of America, 1965.

- Rimmer, R.B.; Fornaciari, G.M.; Foster, K.N.; Bay, C.R.; Wadsworth, M.M; Wood, M.; Caruso, D.M. Impact of a Pediatric Residential Burn Camp Experience on Burn Survivors' Perceptions of Self and Attitudes Regarding the Camp Community. J Burn Care Res. 2007, 28(2), 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong Jones, L.; Cadogan, J.; Williamson, H.; Rumsey, N.; Harcourt, D. An evaluation of the impact of a burn camp on children and young people’s concerns about social situations, satisfaction with appearance and behaviour. Scars, Burns & Healing 2018, 4, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, J.; Heinberg, L.; Roca, R.; Munster, A.; Spence, R.; Fauerbach, J. Development and Validation of the Satisfaction With Appearance Scale: Assessing Body Image Among Burn-Injured Patients. Psychol Assess. 1998, 10(1), 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Burn Care Standards. National Standards for Provision and Outcomes in Adult and Paediatric Burn Care. 2018. Available online: https://www.britishburnassociation.org/standards/ (accessed on 24th April 2023).

- British Burn Association. Psychological Screening and Outcome Measures – November 2008. 20 November.

- Varni, J.M.; Burwinkle, T.M.; Seid, M.; Skarr, D. The PedsQL™ 4.0 as a Pediatric Population Health Measure: Feasibility, Reliability, and Validity. Ambulatory Pediatric 2003, 3(6), 329-341. [CrossRef]

- Perrin, S.; Meiser-Stedman, R.; Smith, P. The Children's Revised Impact of Event Scale (CRIES): Validity as a Screening Instrument for PTSD. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy 2005, 33(4), 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doctor, M.E. Psychosocial Forum. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1997, 18(1), 92–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kornhaber, R.; Visentin, D.; Kaji Thapa, D.; West, S.; Haik, J.; Cleary, M. Burn camps for burns survivors—Realising the benefits for early adjustment: A systematic review. Burns 2020, 46(1), 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Younger Children’s Camp | Older Children’s Camp | |||||||

| Year | Total Number | Girls | Boys | Mean Age | Total Number | Girls | Boys | Mean Age |

| 2010 | 17 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 23 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 2011 | 15 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 21 | 9 | 12 | 13 |

| 2012 | 15 | 9 | 6 | 7 | 21 | 12 | 9 | 13 |

| 2013 | 18 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 24 | 13 | 11 | 12 |

| 2014 | 14 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 22 | 12 | 10 | 12 |

| 2015 | 19 | 8 | 11 | 8 | 24 | 16 | 8 | 13 |

| 2016 | 16 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 25 | 18 | 7 | 13 |

| 2017 | 15 | 9 | 6 | 9 | 28 | 17 | 11 | 12 |

| 2018 | 15 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 27 | 14 | 13 | 13 |

| 2019 | 14 | 8 | 6 | 10 | 27 | 18 | 9 | 14 |

| Question | Theme | Illustrative Quotes |

| (a) Older Children’s Responses | ||

| How has being at camp helped you? (2010 – 2013) |

Meeting children with similar experiences | -I have been able to meet people that suffer from burns and seen that you can still carry out ambitions and goals to whatever extent you want, having a burn doesn’t stop you (2010) -You know you’re not alone and you’re not the only one that has scars (2012) -That other people are burnt too, and you feel more safe (2013) |

| Develop confidence and self-esteem | -Made me feel more confident about my scars and myself (2009) -Got a lot more confidence (2011) -I am more confident showing my burns (2012) |

|

| Explain why you would / would not recommend the camp to someone with burn injuries (2014 – 2019) |

Meeting children with burn injuries and scars | -I think that lots of people that don’t have burns instantly label you and at burns camp that doesn’t happen, you bit by bit become more comfortable in your “burnt” skin and you get to the stage where you’re so comfortable you can make jokes (2014) -It helps you meet other people with burns and also helps you understand and accept your own burns (2015) -It helps you talk to people who have been through the same thing as you (2019) |

| Develops confidence and coping strategies | -It helps you be more confident with your burn (2014) -It’s an opportunity for people with fears to support each other and gain confidence (2016) -It has boosted my confidence about my burn as sometimes I’m not confident about it (2019) |

|

| Camp is great fun |

-I would recommend the camp to someone else because it is really fun (2015) -Camp is a great and wonderful experience which every child who has been burned should try (2016) -I would recommend it to someone else who had been burned because camp is really fun, exciting (2018) |

|

| (b) Younger Children’s Responses | ||

| How has being at camp helped you? (2010 – 2014) |

Develop confidence and self-esteem | -More confidence (2010) -Camp has helped me a lot, it gave me confidence (2012) -Helped me be independent (2014) |

| Explain why you would / would not recommend the camp to someone with burn injuries (2015 – 2019) |

Meeting other children with burn injuries | -You get to meet other children with burns (2015) -They know they are not the only one with a burn (2016) Y-ou can talk to other people about their burns (2019) |

| Develops confidence |

They will take lots and lots of care of you and it will build your confidence in different activities (2016) It builds your confidence (2017) Brings confidence (2018) |

|

| The activities | -It is fun and the activities are good (2015) -You get to do really good activities (2017) -Try new things (2019) |

|

| Question | Theme | Illustrative Quotes | |

| (a) Older Children’s Responses | |||

| In what ways do you think coming to Burns Camp helps people who have been burned? | Meeting children with similar experiences | -Helps you realise you’re not alone and there are people out there who know how you feel and what you’re going through and they can give you advice (2012) -You meet people who have gone through what you went through and it helps by talking to them (2016) -Makes us feel that we are not on our own and there’s other people like us and we can still move on with our life no matter what (2018) |

|

| Develop confidence and self-esteem | -Gives you more confidence (2010) -It gives you the confidence to show your scars without feeling intimidated or embarrassed (2011) -I’ve got a lot more confidence (2017) |

||

| Parent/Carer Responses – Older Children | |||

| How has being at camp helped your child? | Meeting children with similar experiences | -[Name] has been able to meet other children with burns and it made him realise he is not alone (2012) -Meeting other children who had similar experiences and injuries was incredibly important in [Name]’s progress (2016) -Able to see how others deal with their injuries (2019) |

|

| Develop confidence and self-esteem | -Confidence to not be embarrassed by her injuries in public (2010) -Helped with his confidence and how to cope with billies at school (2013) -[Name] is a different child; she no longer thinks she is strange and different; she has confidence in herself (2015) |

||

| What do you think your child gained from coming to camp? | Increased self-confidence, independence, and self-esteem | -It has boosted her self-esteem and confidence levels (2012) -When he faces difficulties, he now always looks for a different way to solve the problem rather than give up (2015) -I noticed a difference in [Name]’s confidence immediately. The child we left to go to camp was anxious, the child we picked up a week later was confident and beaming from the experiences she had had (2018) |

|

| What do you think are the good things about camp? | Meeting children with experience of burn injury | -Meeting others who have experienced trauma and learning how others have dealt with their trauma and subsequent scarring (2011) -[Name] gets to meet people who have been through more or less the same thing as her which makes her feel that she isn’t on her own (2013) -[Name] loved being around other people who have similar issues as her. It’s helped her realised she is not alone. (2014) |

|

| (b) Younger Children’s Responses | |||

| In what ways do you think coming to Burns Camp helps people who have been burned? | Meeting children with similar experiences | -To just see other people burnt and not just feeling that only you have burns (2012) -I think it helps because we can talk to people who have experienced the same things (2014) -It helps to have people around you who have scars like you, you can talk about it if you want to (2018) |

|

| Parent/Carer Responses – Younger Children | |||

| How has being at camp helped your child? | Meeting children with similar experiences | -Meeting other children with burns has helped [Name] realise she’s not the only one (2011) -Has helped [Name] talk with other children about his scar, whereas before he was a bit “sheepish” about it (2013) -Meeting other children who had experienced the same thing, showing him he was not alone has helped with anxiety and coming to terms with his accident (2017) |

|

| What do you think your child gained from coming to camp? | Increased self-confidence, independence, and self-esteem | -Confidence, showed [Name] her injury should not physically restrict her in life (2013) -[Name] gained confidence and seems to be mixing more with other kids rather than playing on her own (2016) -[Name] has become more independent (2019) |

|

| What do you think are the good things about camp? | Meeting children with experience of burn injury | -He learnt that others have injuries and is less embarrassed, he is less aggressive with family members (2012) -I am happy my child had a chance to meet other young people with similar injuries (2015) -All the kids can relate to each other with their burns and they can build each other’s confidence (2017) |

|

| Increased self-confidence, independence, and self-esteem | -Helped my son be more confident (2014) -Her improved self-esteem has made a big impact on her socially (2016) -It teaches a child to be confident and independent and gives them a feeling of belonging (2019) |

||

| Camp programme | -There are loads of well organised activities (2011) -The activities are incredible (2014) -The activities and doing things in the camp (2018) |

||

| Question | Theme | Illustrative Quotes |

| Did you feel the children gained anything from Camp? | Develop confidence and self-esteem | -All the children grew in confidence over the week and were able to try lots of activities they had never done before, or thought that they would be able to do but did (2013-YC) -Increased confidence, especially around body image (2011-OC) -You could see the confidence of a new camper in my group grow, he talked about his burn injury with the other children openly and joined in the public swimming session at the end of the week with no difficulties (2013-OC) |

| What do you think worked well at Camp? | Camp leader team | -We had an amazing group of leaders who worked really well together and provided a good skill mix to meet the needs of the group (2019-YC) -We had a really good staff team who worked well together and put a lot of effort into making the campers feel safe and supported (2017-OC) -Having previous campers now as adult leaders has an obvious positive message, I thought their contribution was invaluable this year (2019-OC) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).