Submitted:

16 June 2023

Posted:

16 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Overlap between MAFLD and DKD

2.1. Epidemiologic perspective

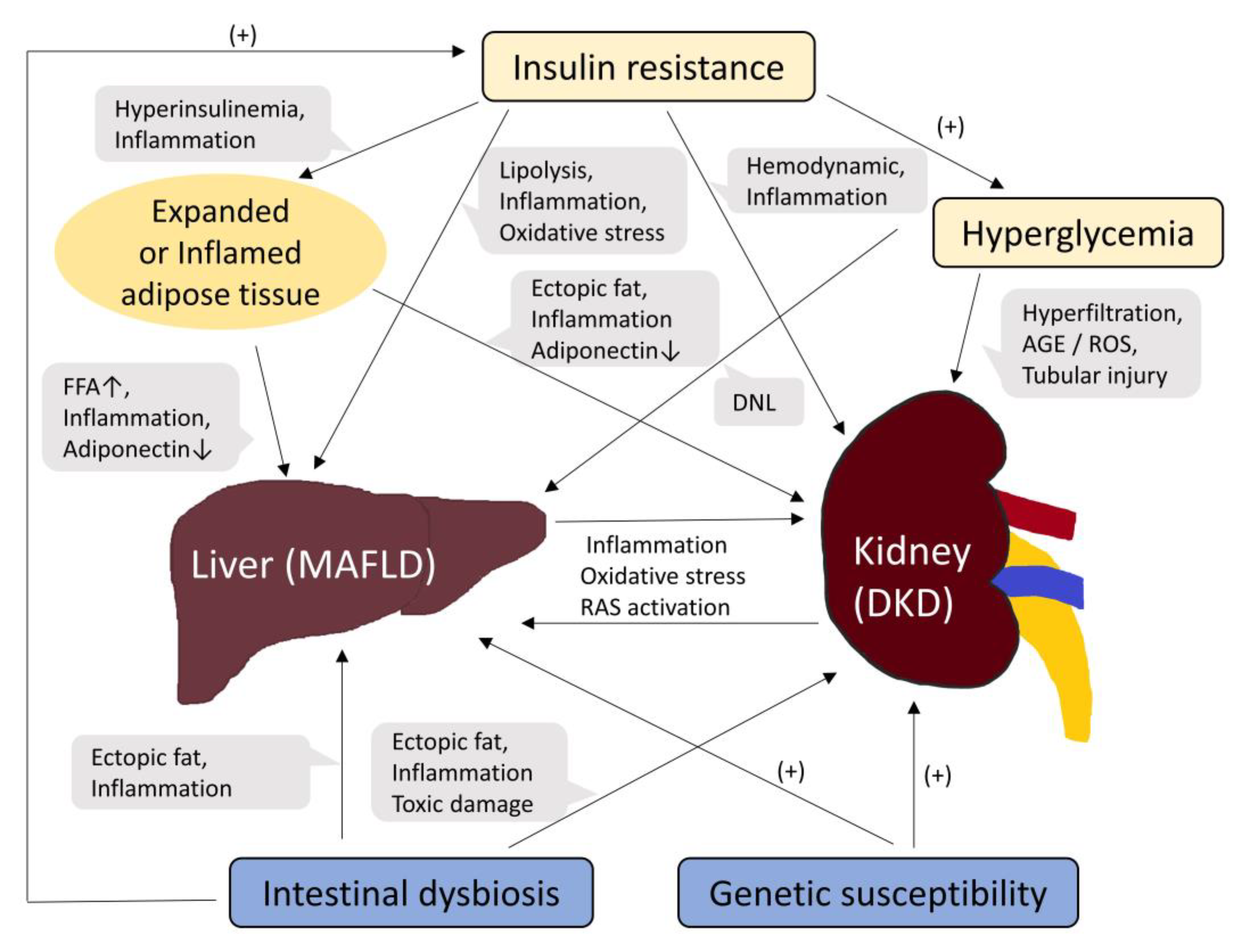

2.2. Pathophysiological mechanisms linking MAFLD and DKD

3. Biomarkers of DKD and MAFLD

3.1. Conventional glomerular biomarkers: albuminuria and eGFR

3.2. Biomarkers for renal tubular injury

4. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Diehl, A.M.; Day, C. Cause, pathogenesis, and treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. New Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 2063–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Golabi, P.; Paik, J.M.; Henry, A.; Van Dongen, C.; Henry, L. The global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): a systematic review. Hepatology 2023, 77, 1335–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.H.; Cho, Y.; Lee, B.W.; Park, C.Y.; Lee, D.H.; Cha, B.S.; Rhee, E.J. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in diabetes. Part i: Epidemiology and diagnosis. Diabetes Metab. J. 2019, 43, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Golabi, P.; de Avila, L.; Paik, J.M.; Srishord, M.; Fukui, N.; Qiu, Y.; Burns, L.; Afendy, A.; Nader, F. The global epidemiology of NAFLD and NASH in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Hepatol. 2019, 71, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslam, M.; Sanyal, A.J.; George, J.; on behalf of theInternational Consensus Panel. MAFLD: A Consensus-Driven Proposed Nomenclature for Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 1999–2014.e1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, M.T.; Hemmelgarn, B.R.; Tonelli, M. Early recognition and prevention of chronic kidney disease. Lancet 2010, 375, 1296–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD_Chronic_Kidney_Disease_Collaboration. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990-2017: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet 2020, 395, 709–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovesdy, C.P. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease: an update 2022. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2022, 12, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alicic, R.Z.; Rooney, M.T.; Tuttle, K.R. Diabetic kidney disease: Challenges, progress, and possibilities. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. : CJASN 2017, 12, 2032–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Targher, G.; Chonchol, M.B.; Byrne, C.D. Ckd and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am. J. Kidney Dis. : Off. J. Natl. Kidney Found. 2014, 64, 638–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musso, G.; Gambino, R.; Tabibian, J.H.; Ekstedt, M.; Kechagias, S.; Hamaguchi, M.; Hultcrantz, R.; Hagström, H.; Yoon, S.K.; Charatcharoenwitthaya, P.; et al. Association of Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease with Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. PLOS Med. 2014, 11, e1001680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantovani, A.; Zaza, G.; Byrne, C.D.; Lonardo, A.; Zoppini, G.; Bonora, E.; Targher, G. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease increases risk of incident chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Metabolism 2017, 79, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Targher, G.; Bertolini, L.; Rodella, S.; Zoppini, G.; Lippi, G.; Day, C.; Muggeo, M. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is independently associated with an increased prevalence of chronic kidney disease and proliferative/laser-treated retinopathy in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetologia 2008, 51, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Targher, G.; Chonchol, M.; Bertolini, L.; Rodella, S.; Zenari, L.; Lippi, G.; Franchini, M.; Zoppini, G.; Muggeo, M. Increased Risk of CKD among Type 2 Diabetics with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2008, 19, 1564–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, G.; Di, F.; Wang, Q.; Shao, J.; Gao, L.; Wang, L.; Li, Q.; Li, N. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Is a Risk Factor for the Development of Diabetic Nephropathy in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0142808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, D.H.; Suh, Y.J.; Cho, Y.; Ahn, S.H.; Seo, S.; Hong, S.; Lee, Y.-H.; Choi, Y.J.; Lee, E.; Kim, S.H. Advanced Liver Fibrosis Is Associated with Chronic Kidney Disease in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Diabetes Metab. J. 2022, 46, 630–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Hong, L.; Huang, Z.; Wang, L.; Xiong, Y.; Zong, S.; Zhang, R.; Liu, J.; Zang, S. Fibrosis Risk in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Is Related to Chronic Kidney Disease in Older Type 2 Diabetes Patients. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 107, e3661–e3669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Targher, G.; Mantovani, A.; Pichiri, I.; Mingolla, L.; Cavalieri, V.; Mantovani, W.; Pancheri, S.; Trombetta, M.; Zoppini, G.; Chonchol, M.; et al. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Is Independently Associated With an Increased Incidence of Chronic Kidney Disease in Patients With Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 1729–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhu, S.; Li, B.; Shao, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, A.; Wu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; et al. Association between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and chronic kidney disease in population with prediabetes or diabetes. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2014, 46, 1785–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A.; Turino, T.; Lando, M.G.; Gjini, K.; Byrne, C.D.; Zusi, C.; Ravaioli, F.; Colecchia, A.; Maffeis, C.; Salvagno, G.; et al. Screening for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease using liver stiffness measurement and its association with chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2019, 46, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, P.; Yan, J.; Pan, B.; Liu, J.; Fu, S.; Cheng, J.; Wang, L.; Jing, G.; Li, Q. Association Between the Risk of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Chronic Kidney Disease. Diabetes, Metab. Syndr. Obesity: Targets Ther. 1141; 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Song, J.; Xie, Y.; Huang, J.; Yang, J. Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease can significantly increase the risk of chronic kidney disease in adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pr. 2023, 197, 110563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moh, M.C.; Pek, S.L.T.; Sze, K.C.P.; Low, S.; Subramaniam, T.; Ang, K.; Tang, W.E.; Lee, S.B.M.; Sum, C.F.; Lim, S.C. Associations of non-invasive indices of liver steatosis and fibrosis with progressive kidney impairment in adults with type 2 diabetes. Acta Diabetol. 2023, 60, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeung, M.-W.; Wong, G.L.-H.; Choi, K.C.; Luk, A.O.-Y.; Kwok, R.; Shu, S.S.-T.; Chan, A.W.-H.; Lau, E.S.H.; Ma, R.C.W.; Chan, H.L.-Y.; et al. Advanced liver fibrosis but not steatosis is independently associated with albuminuria in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes. J. Hepatol. 2017, 68, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciardullo, S.; Muraca, E.; Perra, S.; Bianconi, E.; Zerbini, F.; Oltolini, A.; Cannistraci, R.; Parmeggiani, P.; Manzoni, G.; Gastaldelli, A.; et al. Screening for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in type 2 diabetes using non-invasive scores and association with diabetic complications. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2020, 8, e000904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, E.; Kim, M.K.; Jang, B.K.; Kim, H.S. Albuminuria Is Associated with Steatosis Burden in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Diabetes Metab. J. 2021, 45, 698–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Wan, H.; Chen, Y.; Xia, F.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, K.; Gu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, Z.; et al. Lower eGFR is associated with increased probability of liver fibrosis in Chinese diabetic patients. Diabetes/Metabolism Res. Rev. 2020, 36, e3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, E.; Cho, Y.; Kim, K.-W.; Lee, Y.-H.; Kang, E.S.; Cha, B.-S.; Lee, B.-W. Hepatic fibrosis is associated with total proteinuria in Korean patients with type 2 diabetes. Medicine 2020, 99, e21038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.K.; Lee, M.; Lee, Y.-H.; Kang, E.S.; Cha, B.-S.; Lee, B.-W. Renal Tubular Damage Marker, Urinary N-acetyl-β-D-Glucosaminidase, as a Predictive Marker of Hepatic Fibrosis in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Metab. J. 2022, 46, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truong, E.; Noureddin, M. The Interplay Between Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Kidney Disease. Clin. Liver Dis. 2022, 26, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdomo, C.M.; Frühbeck, G.; Escalada, J. Impact of Nutritional Changes on Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Nutrients 2019, 11, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C.P.; James, O.F. Steatohepatitis: A tale of two "hits"? Gastroenterology 1998, 114, 842–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, S.L.; Neuschwander-Tetri, B.A.; Rinella, M.; Sanyal, A.J. Mechanisms of NAFLD development and therapeutic strategies. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 908–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Targher, G.; Chonchol, M.; Miele, L.; Zoppini, G.; Pichiri, I.; Muggeo, M. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease as a Contributor to Hypercoagulation and Thrombophilia in the Metabolic Syndrome. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2009, 35, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alicic, R.Z.; Johnson, E.J.; Tuttle, K.R. Inflammatory Mechanisms as New Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets for Diabetic Kidney Disease. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2018, 25, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuttle, K.R.; Agarwal, R.; Alpers, C.E.; Bakris, G.L.; Brosius, F.C.; Kolkhof, P.; Uribarri, J. Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets for diabetic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2022, 102, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olejnik, A.; Franczak, A.; Krzywonos-Zawadzka, A.; Kałużna-Oleksy, M.; Bil-Lula, I. The biological role of klotho protein in the development of cardiovascular diseases. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 5171945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoto, B.; Pisano, A.; Zoccali, C. Insulin resistance in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2016, 311, F1087–F1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoelson, S.E.; Herrero, L.; Naaz, A. Obesity, inflammation, and insulin resistance. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 2169–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, C.D. Dorothy Hodgkin Lecture 2012* Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, insulin resistance and ectopic fat: a new problem in diabetes management. Diabet. Med. 2012, 29, 1098–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deji, N.; Kume, S.; Araki, S.-I.; Soumura, M.; Sugimoto, T.; Isshiki, K.; Chin-Kanasaki, M.; Sakaguchi, M.; Koya, D.; Haneda, M.; et al. Structural and functional changes in the kidneys of high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2009, 296, F118–F126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobulescu, I.A.; Dubree, M.; Zhang, J.; McLeroy, P.; Moe, O.W. Effect of renal lipid accumulation on proximal tubule Na+/h+ exchange and ammonium secretion. American journal of physiology. Renal physiology 2008, 294, F1315–F1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Sircar, A.; Anders, H.-J.; Gaikwad, A.B. Crosstalk between kidney and liver in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: mechanisms and therapeutic approaches. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 128, 1024–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ix, J.H.; Sharma, K. Mechanisms linking obesity, chronic kidney disease, and fatty liver disease: The roles of fetuin-a, adiponectin, and ampk. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN 2010, 21, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Icer, M.A.; Yıldıran, H. Effects of nutritional status on serum fetuin-A level. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 60, 1938–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennige, A.M.; Staiger, H.; Wicke, C.; Machicao, F.; Fritsche, A.; Häring, H.-U.; Stefan, N. Fetuin-A Induces Cytokine Expression and Suppresses Adiponectin Production. PLOS ONE 2008, 3, e1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, H.; Zhou, Z.; Sun, M.; Chen, H. Association of fetuin-A to adiponectin ratio with metabolic syndrome: a cross-sectional study. Endocrine 2017, 58, 190–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, C.D.; Targher, G. NAFLD as a driver of chronic kidney disease. J. Hepatol. 2020, 72, 785–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perdomo, C.M.; Garcia-Fernandez, N.; Escalada, J. Diabetic kidney disease, cardiovascular disease and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A new triumvirate? J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, L.; Duffy, A. Factors Influencing the Gut Microbiota, Inflammation, and Type 2 Diabetes. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 1468S–1475S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, F.W.B.; Griffin, J.L. De novo lipogenesis in the liver in health and disease: more than just a shunting yard for glucose. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2016, 91, 452–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeFronzo, R.A.; Hompesch, M.; Kasichayanula, S.; Liu, X.; Hong, Y.; Pfister, M.; Morrow, L.A.; Leslie, B.R.; Boulton, D.W.; Ching, A.; et al. Characterization of Renal Glucose Reabsorption in Response to Dapagliflozin in Healthy Subjects and Subjects With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 3169–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C.; Stumvoll, M.; Nadkarni, V.; Dostou, J.; Mitrakou, A.; Gerich, J. Abnormal renal and hepatic glucose metabolism in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Investig. 1998, 102, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körner, A.; Eklöf, A.C.; Celsi, G.; Aperia, A. Increased renal metabolism in diabetes. Mechanism and functional implications. Diabetes 1994, 43, 629–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, M.; Usman, I.M.; Sun, L.; Kanwar, Y.S. Disruption of Renal Tubular Mitochondrial Quality Control by Myo-Inositol Oxygenase in Diabetic Kidney Disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015, 26, 1304–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindenmeyer, M.T.; Kretzler, M.; Boucherot, A.; Berra, S.; Yasuda, Y.; Henger, A.; Eichinger, F.; Gaiser, S.; Schmid, H.; Rastaldi, M.P.; et al. Interstitial Vascular Rarefaction and Reduced VEGF-A Expression in Human Diabetic Nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2007, 18, 1765–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, J.; Won, Y.J.; Lee, B.-W. Non-Albumin Proteinuria (NAP) as a Complementary Marker for Diabetic Kidney Disease (DKD). Life 2021, 11, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcuccilli, M.; Chonchol, M. Nafld and chronic kidney disease. International journal of molecular sciences 2016, 17, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, E.M.; Fletcher, J.A.; Thyfault, J.P.; Rector, R.S. The role of angiotensin II in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2013, 378, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musso, G.; Cassader, M.; Cohney, S.; Pinach, S.; Saba, F.; Gambino, R. Emerging Liver–Kidney Interactions in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Trends Mol. Med. 2015, 21, 645–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chawla, T.; Sharma, D.; Singh, A. Role of the renin angiotensin system in diabetic nephropathy. World J. Diabetes 2010, 1, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Gao, W.; Xu, H.; Liang, W.; Ma, G. Role and Mechanism of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System in the Onset and Development of Cardiorenal Syndrome. J. Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone Syst. 2022, 2022, 3239057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romeo, S.; Kozlitina, J.; Xing, C.; Pertsemlidis, A.; Cox, D.; Pennacchio, L.A.; Boerwinkle, E.; Cohen, J.C.; Hobbs, H.H. Genetic variation in PNPLA3 confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat. Genet. 2008, 40, 1461–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirazzi, C.; Valenti, L.; Motta, B.M.; Pingitore, P.; Hedfalk, K.; Mancina, R.M.; Burza, M.A.; Indiveri, C.; Ferro, Y.; Montalcini, T.; et al. PNPLA3 has retinyl-palmitate lipase activity in human hepatic stellate cells. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 4077–4085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vespasiani-Gentilucci, U.; Gallo, P.; Dell’unto, C.; Volpentesta, M.; Antonelli-Incalzi, R.; Picardi, A. Promoting genetics in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Combined risk score through polymorphisms and clinical variables. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 4835–4845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Targher, G.; Mantovani, A.; Alisi, A.; Mosca, A.; Panera, N.; Byrne, C.D.; Nobili, V. Relationship Between PNPLA3 rs738409 Polymorphism and Decreased Kidney Function in Children With NAFLD. Hepatology 2019, 70, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oniki, K.; Saruwatari, J.; Izuka, T.; Kajiwara, A.; Morita, K.; Sakata, M.; Otake, K.; Ogata, Y.; Nakagawa, K. Influence of the PNPLA3 rs738409 Polymorphism on Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Renal Function among Normal Weight Subjects. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0132640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musso, G.; Cassader, M.; Gambino, R. PNPLA3 rs738409 and TM6SF2 rs58542926 gene variants affect renal disease and function in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2014, 62, 658–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simons, P.I.H.G.; Simons, N.; Stehouwer, C.D.A.; Schalkwijk, C.G.; Schaper, N.C.; Brouwers, M.C.G.J. Association of common gene variants in glucokinase regulatory protein with cardiorenal disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0206174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.-Y.; Wang, R.-F.; Bu, Z.-Y.; Targher, G.; Byrne, C.D.; Sun, D.-Q.; Zheng, M.-H. Association of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease with kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2022, 18, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuttle, K.R.; Bakris, G.L.; Bilous, R.W.; Chiang, J.L.; de Boer, I.H.; Goldstein-Fuchs, J.; Hirsch, I.B.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Narva, A.S.; Navaneethan, S.D.; et al. Diabetic Kidney Disease: A Report From an ADA Consensus Conference. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 2864–2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ElSayed, N.A.; Aleppo, G.; Aroda, V.R.; Bannuru, R.R.; Brown, F.M.; Bruemmer, D.; Collins, B.S.; Hilliard, M.E.; Isaacs, D.; Johnson, E.L.; et al. 11. Chronic Kidney Disease and Risk Management: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2023. Diabetes Care 2022, 46, S191–S202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parving, H.H. Microalbuminuria in essential hypertension and diabetes mellitus. Journal of hypertension. Supplement : official journal of the International Society of Hypertension 1996, 14, S89–S93 discussion S93-84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satchell, S.C.; Tooke, J.E. What is the mechanism of microalbuminuria in diabetes: A role for the glomerular endothelium? Diabetologia 2008, 51, 714–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, P.E.; Levin, A. Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease: Synopsis of the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes 2012 Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013, 158, 825–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pugliese, G. Updating the natural history of diabetic nephropathy. Acta Diabetol. 2014, 51, 905–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijarnpreecha, K.; Thongprayoon, C.; Boonpheng, B.; Panjawatanan, P.; Sharma, K.; Ungprasert, P.; Pungpapong, S.; Cheungpasitporn, W. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and albuminuria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 30, 986–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niskanen, L.; Laakso, M. Insulin resistance is related to albuminuria in patients with type II (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Metabolism 1993, 42, 1541–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujikawa, R.; Okubo, M.; Egusa, G.; Kohno, N. Insulin resistance precedes the appearance of albuminuria in non-diabetic subjects: 6 years follow up study. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pr. 2001, 53, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tervaert, T.W.; Mooyaart, A.L.; Amann, K.; Cohen, A.H.; Cook, H.T.; Drachenberg, C.B.; Ferrario, F.; Fogo, A.B.; Haas, M.; de Heer, E. Pathologic classification of diabetic nephropathy. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN 2010, 21, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, R.E.; Cooper, M.E. The tubulointerstitium in progressive diabetic kidney disease: More than an aftermath of glomerular injury? Kidney Int. 1999, 56, 1627–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, R.E. Proximal Tubulopathy: Prime Mover and Key Therapeutic Target in Diabetic Kidney Disease. Diabetes 2017, 66, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Retnakaran, R.; Cull, C.A.; Thorne, K.I.; Adler, A.I.; Holman, R.R. Risk factors for renal dysfunction in type 2 diabetes: U.K. Prospective diabetes study 74. Diabetes 2006, 55, 1832–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krolewski, A.S. Progressive Renal Decline: The New Paradigm of Diabetic Nephropathy in Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2015, 38, 954–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yacoub, R.; Campbell, K.N. Inhibition of ras in diabetic nephropathy. International journal of nephrology and renovascular disease 2015, 8, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallon, V.; Pirklbauer, M.; Schupart, R.; Fuchs, L.; Staudinger, P.; Corazza, U.; Sallaberger, S.; Leierer, J.; Mayer, G.; Schramek, H.; et al. The proximal tubule in the pathophysiology of the diabetic kidney. Am. J. Physiol. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2011, 300, R1009–R1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assal, H.S.; Tawfeek, S.; Rasheed, E.A.; El-Lebedy, D.; Thabet, E.H. Serum Cystatin C and Tubular Urinary Enzymes as Biomarkers of Renal Dysfunction in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Clin. Med. Insights: Endocrinol. Diabetes 2013, 6, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi-Karakani, A.; Asgharzadeh-Haghighi, S.; Ghazi-Khansari, M.; Hosseini, R. Determination of urinary enzymes as a marker of early renal damage in diabetic patients. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2007, 21, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Fei, X.; Zhan, H.; Gong, J.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, X.; Song, Y.; Ma, J.; Wu, X. Urinary n-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminidase-creatine ratio is a valuable predictor for advanced diabetic kidney disease. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2023, 37, e24769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, N.; Lee, M.; Park, S.; Lee, Y.-H.; Jin, S.-M.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, B.-W. Elevated urinary N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase is associated with high glycoalbumin-to-hemoglobin A1c ratio in type 1 diabetes patients with early diabetic kidney disease. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.R.; Lee, Y.-H.; Lee, S.-G.; Kang, E.S.; Cha, B.-S.; Kim, J.-H.; Lee, B.-W. Urinary N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase, an early marker of diabetic kidney disease, might reflect glucose excursion in patients with type 2 diabetes. Medicine 2016, 95, e4114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiseha, T.; Tamir, Z. Urinary Markers of Tubular Injury in Early Diabetic Nephropathy. Int. J. Nephrol. 2016, 2016, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.Y.; Jeong, T.-D.; Lee, W.; Chun, S.; Sunwoo, S.; Kim, S.B.; Min, W.-K. Plasma Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin as a Marker of Tubular Damage in Diabetic Nephropathy. Ann. Lab. Med. 2018, 38, 524–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hur, M.; Kim, H.; Lee, S.; Cristofano, F.; Magrini, L.; Marino, R.; Gori, C.S.; Bongiovanni, C.; Zancla, B.; Cardelli, P.; et al. Diagnostic and prognostic utilities of multimarkers approach using procalcitonin, B-type natriuretic peptide, and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in critically ill patients with suspected sepsis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 224–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.S.; Song, S.H.; Kim, I.J.; Yang, J.Y.; Lee, J.G.; Kwak, I.S.; Kim, Y.K. Clinical implication of urinary tubular markers in the early stage of nephropathy with type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pr. 2012, 97, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.-H.; Yang, F.-J.; Tsai, W.-Y.; Lee, C.-T.; Liu, S.-Y.; Yang, W.-S.; Tung, Y.-C. Serum neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin as a potential biomarker of diabetic kidney disease in patients with childhood-onset type 1 diabetes. J. Formos. Med Assoc. 2021, 121, 832–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamijo-Ikemori, A.; Sugaya, T.; Kimura, K. Novel Urinary Biomarkers in Early Diabetic Kidney Disease. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2014, 14, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamijo-Ikemori, A.; Sugaya, T.; Yasuda, T.; Kawata, T.; Ota, A.; Tatsunami, S.; Kaise, R.; Ishimitsu, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Kimura, K. Clinical Significance of Urinary Liver-Type Fatty Acid–Binding Protein in Diabetic Nephropathy of Type 2 Diabetic Patients. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 691–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S.E.; Sugaya, T.; Hovind, P.; Baba, T.; Parving, H.-H.; Rossing, P. Urinary Liver-Type Fatty Acid-Binding Protein Predicts Progression to Nephropathy in Type 1 Diabetic Patients. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 1320–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panduru, N.M.; Forsblom, C.; Saraheimo, M.; Thorn, L.; Bierhaus, A.; Humpert, P.M.; Groop, P.-H. ; on behalf of the FinnDiane Study Group Urinary Liver-Type Fatty Acid–Binding Protein and Progression of Diabetic Nephropathy in Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 2077–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, K.; Babazono, T.; Murata, H.; Iwamoto, Y. Clinical Significance of Urinary Liver-Type Fatty Acid–Binding Protein in Patients With Diabetic Nephropathy. Diabetes Care 2005, 28, 2038–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonventre, J.V. Kidney injury molecule-1 (kim-1): A urinary biomarker and much more. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association 2009, 24, 3265–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.K.; Bailly, V.; Abichandani, R.; Thadhani, R.; Bonventre, J.V. Kidney Injury Molecule-1 (KIM-1): A novel biomarker for human renal proximal tubule injury. Kidney Int. 2002, 62, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nauta, F.L.; Boertien, W.E.; Bakker, S.J.; van Goor, H.; van Oeveren, W.; de Jong, P.E.; Bilo, H.; Gansevoort, R.T. Glomerular and Tubular Damage Markers Are Elevated in Patients With Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 975–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, X.; Zhu, J.L.; Li, Y.; Luo, W.W.; Xiang, H.R.; Zhang, Q.Z.; Peng, W.X. Serum biomarkers of isoniazid-induced liver injury: Aminotransferases are insufficient, and opn, l-fabp and hmgb1 can be promising novel biomarkers. Journal of applied toxicology : JAT 2022, 42, 516–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juanola, A.; Graupera, I.; Elia, C.; Piano, S.; Solé, C.; Carol, M.; Pérez-Guasch, M.; Bassegoda, O.; Escudé, L.; Rubio, A.-B.; et al. Urinary L-FABP is a promising prognostic biomarker of ACLF and mortality in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 2021, 76, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariza, X.; Graupera, I.; Coll, M.; Solà, E.; Barreto, R.; García, E.; Moreira, R.; Elia, C.; Morales-Ruiz, M.; Llopis, M.; et al. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin is a biomarker of acute-on-chronic liver failure and prognosis in cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 2016, 65, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshikawa, K.; Iwasa, M.; Eguchi, A.; Kojima, S.; Yoshizawa, N.; Tempaku, M.; Sugimoto, R.; Yamamoto, N.; Sugimoto, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; et al. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin level is a prognostic factor for survival in rat and human chronic liver diseases. Hepatol. Commun. 2017, 1, 946–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Design | Patients | Independent variable |

Dependent variable |

Main finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-sectional [13] | 2103 T2D patients | MAFLD by ultrasound | UACR>30mg/g and/or eGFR< 60 mL/min/1.73m2 | OR 1.87; 95% CI 1.3 to 4.1 |

| Cohort [14] | 1760 T2D patients | MAFLD by ultrasound | UACR>30mg/g and/or eGFR< 60 mL/min/1.73m2 | HR 1.69; 95% CI 1.3 to 2.6 |

| Cohort [15] | 169 T2D matched pairs | MAFLD severity by ultrasound | Incidence of albuminuria (24-hour urine albumin > 30mg) |

Increased more in the severe MAFLD group |

| Change in eGFR | Decreased more in the severe MAFLD group | |||

| Cohort [16] | 1729 patients with T2D and MAFLD | FIB-4 index ≥ 2.67 | eGFR< 60 mL/min/1.73m2 | HR 1.75; 95% CI 1.15 to 2.66 |

| Cohort [17] | 1734 T2D patients | FIB-4 index 1.30-3.25 | eGFR< 60 mL/min/1.73m2 | HR 1.27; 95% CI 1.06 to 1.51 |

| FIB-4 index > 3.25 | HR 2.52 95% CI 1.97 to 3.21 | |||

| Cross-sectional [17] | 3445 T2D patients | FIB-4 index 1.30-3.25 | eGFR< 60 mL/min/1.73m2 | OR 1.52; 95% CI 1.12 to 2.07 |

| FIB-4 index > 3.25 | OR 3.62; 95% CI 2.26 to 5.80 | |||

| Cohort [22] | 3627 T2D patients | MAFLD by ultrasound | eGFR< 60 mL/min/1.73m2 or ≥2 proteinuria by dipstick |

HR 1·30; 95 % CI 1·11 to 1·53 |

| Cohort [23] | 2057 T2D patients | Liver steatosis (HSI, ZJU) | Albuminuria progression* | HR 1.02; 95% CI 1.00 to 1.03 |

| Liver fibrosis (BARD) | ≥ 40% eGFR decline | HR 1.12; 95% CI 1.01 to 1.24 | ||

| Cross-sectional [24] | 1763 T2D patients | Liver fibrosis by transient elastography | Incidence of albuminuria (UACR ≥ 3.5 mg/mmol in women and ≥ 2.5 mg/mmol in men) |

OR 1.52; 95% CI 1.02 to 2.28 |

| Cross-sectional [25] | 2770 T2D patients | Fatty liver index (FLI) | UACR > 30mg/g | OR 3.49; 95% CI 2.05 to 5.94 |

| eGFR< 60 mL/min/1.73m2 | OR 1.77; 95% CI 1.15 to 2.72 | |||

| Cross-sectional [26] | 100 T2D patients | UACR ≥ 30mg/g | MAFLD by transient elastography | OR 1.88; 95% CI 1.31 to 2.71 |

| Cross-sectional [21] | 1168 T2D patients | UACR ≥ 300mg/g | MAFLD by ultrasound | OR 2.34; 95% CI 1.20 to 4.56 (vs. UACR<30mg/g) |

| Cross-sectional [27] | 2689 T2D patients | eGFR | Hepatic fibrosis by NFS (>0.676) | OR 0.26; 95% CI 0.09 to 0.74 |

| Cross-sectional [28] | 1108 T2D patients | UACR ≥ 30 mg/g | Hepatic steatosis by NLFS | OR 1.56; 95% CI 1.01 to 2.40 |

| UPCR ≥ 150 mg/g | Hepatic fibrosis by NFS | OR 1.55; 95% CI 1.03 to 2.33 | ||

| Cross-sectional [29] | 300 T2D patients | Urinary NAG | Hepatic fibrosis by transient elastography | F2: OR 1.99; 95% CI 1.04 to 3.82 |

| F3,4: OR 2.4; 95% CI 1.52 to 3.80 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).