Submitted:

19 June 2023

Posted:

20 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Key points

- Different philosophical world views can provide reasons for creating variants of established qualitative methodologies. A good example of this is grounded theory. One variant of grounded theory particularly suited to theory development and research with oppressed groups is social constructivist grounded theory. The current research considers the methods of social constructivist grounded theory and integrated them into a variant of meta-ethnography. The result of this process provides an adapted meta-ethnographic approach situated as a social constructivist.

- Meta-ethnography was originally designed as a theory generating review process. However, despite framework developments many meta-ethnography reviews develop thematic based results. The current framework was developed to account for the need to change the linear phases of meta-ethnography into iterative phases of theory development.

- Qualitative research is often written within a specific population group. This provides unique insight towards the culture, language, behaviours, and actions of the group. Capturing this information helps illustrate how they experience the world and interact with others. Meta-ethnography was originally designed to only include a few studies so that unique world views could be honoured. Social constructivist meta-ethnography employs methodological self-consciousness as a method to honour these unique perspectives including perspectives of oppressed groups.

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Study eligibility

Search strategy

Study selection and extraction

Synthesis

Results

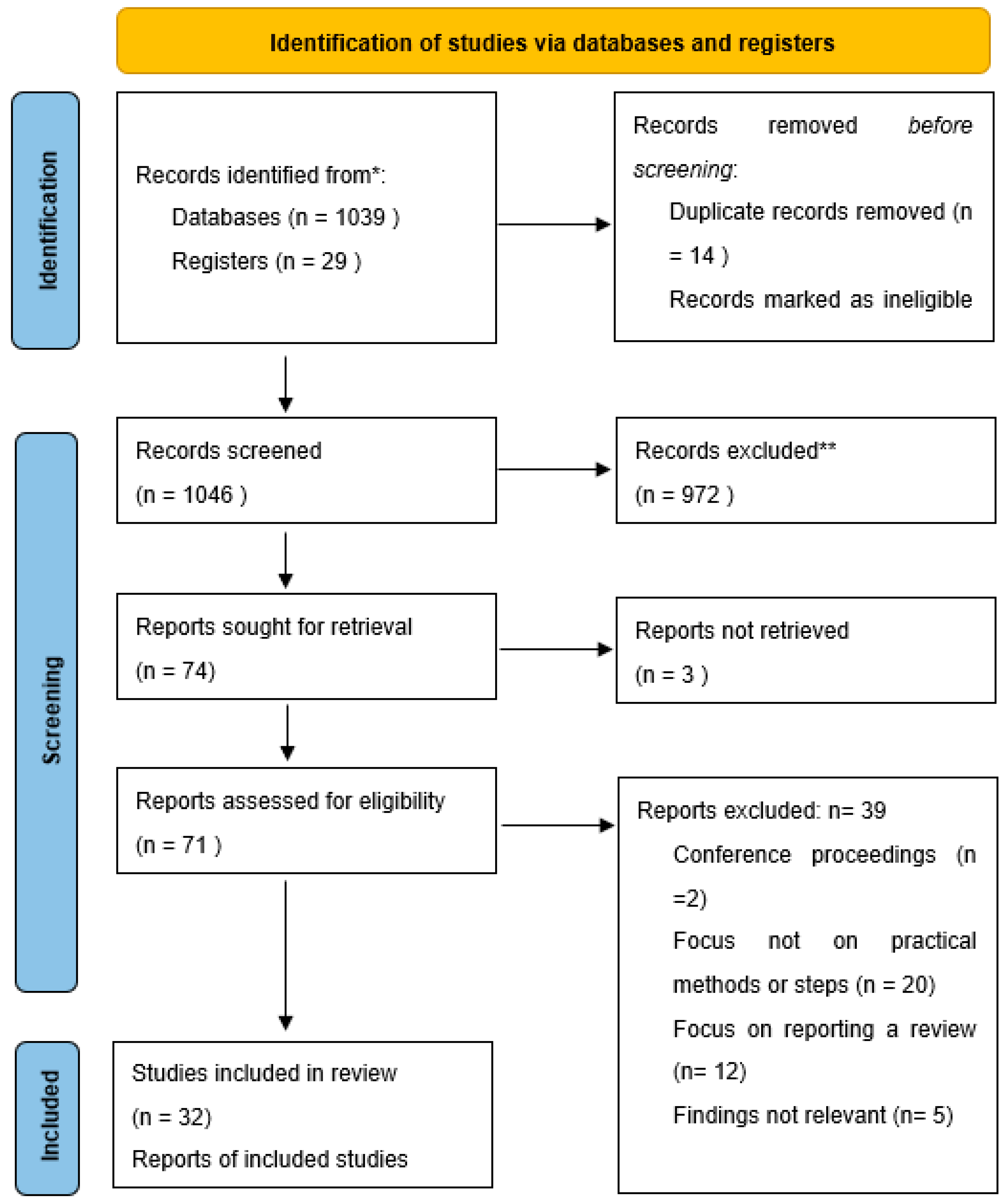

Search output

Synthesis

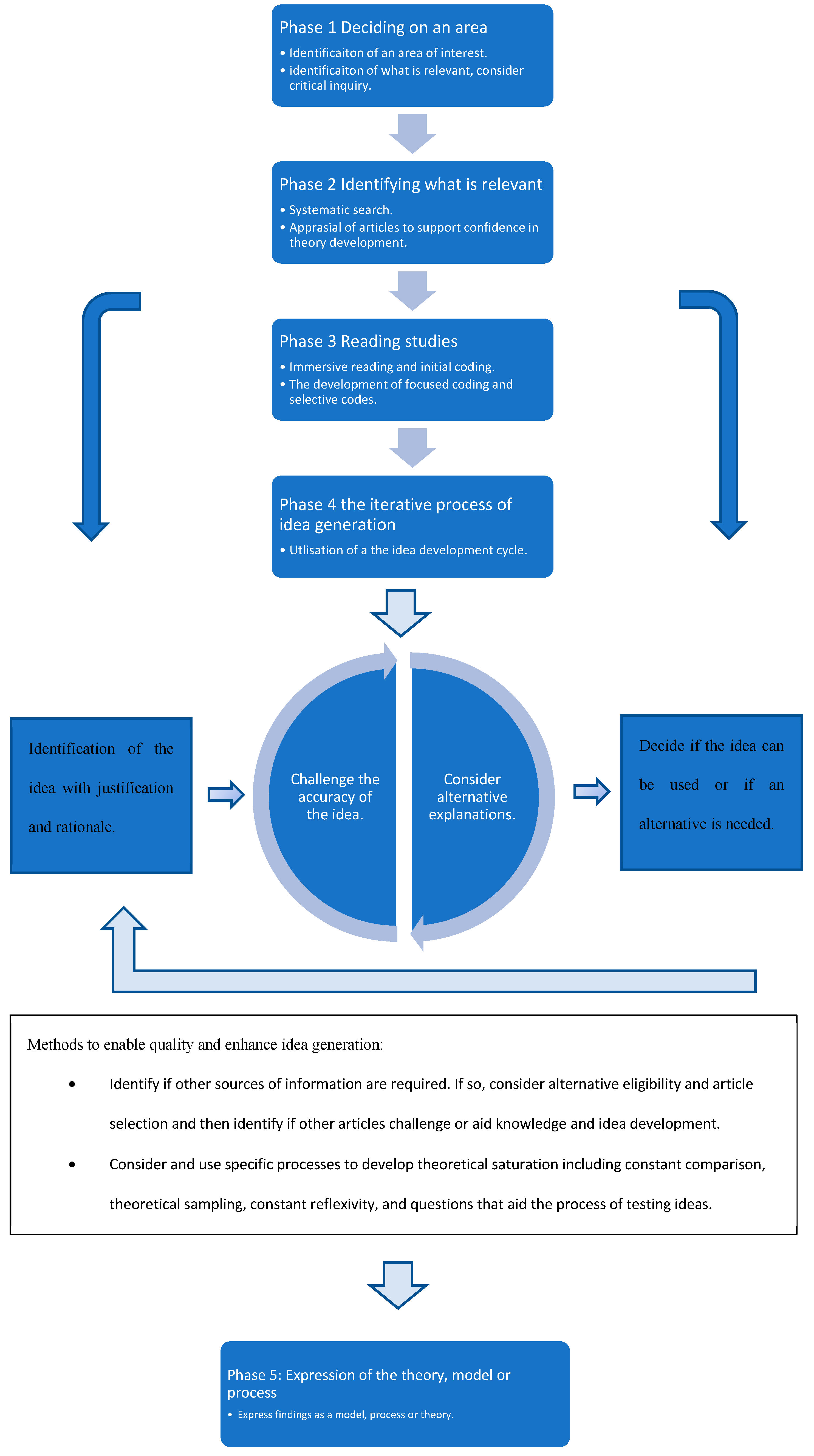

Phase 1 The positionality of the researcher and the area of interest identified

Phase 2 identifying what is relevant

2a Search strategy

- A systematic phase of searching should be undertaken initially using previously identified methods (France et al., 2019a; Soundy & Heneghan, 2022).

- Searching should also be considered as part of iterative processes required that enable the analytic focus to emerge. Phase 4 provides considerations needed for further searching.

2b Critical appraisal

- For this framework quality and confidence will focus on questions that relate to establishing a robust resultant model, process, or theory. A requirement is not made for the traditional appraisal of articles. Soundy and Heneghan (2022) consider the reason for this choice further.

- The following questions could be one way to ensure quality within this type of meta-ethnography. These questions are taken from Soundy and Heneghan (2022) and Toye et al., (2013). They represent one aspect of this process that helps meet the aims of critical inquiry (Charmaz, 2021). The questions can be asked at this point in the process but also during later searching. The questions include: (a) Are considerations and information given by the selected articles made sufficiently well so that concepts can be translated? (b) Do findings provide a context for the culture, environment, and setting? (c) Are the findings relevant and useful given the focus or aims of the analysis now? (d) Do the questions asked or aims from the paper selected align to those sought by the meta-ethnographer? And (e) To what extent do the findings give theoretical insight and context of interpretation made?

- The questions will provide a rationale to include or exclude an article. They should also be used as part of a reflexive process. Answers should be documented to help consider the focus, aims, and thought processes or conversations. The questions can be re-used within phase 4 when further searching occurs.

Phase 4: The iterative process of idea generation required for theory generation

Identification of the idea

- The idea development cycle will test information developed using the information gained from the above phase and methods used including methods identified in phase 3a. This should be considered as an iterative process.

- The processes of idea generation should take place with the following in mind. First, Charmaz (2017) identifies the importance of abduction as a central process for social constructivist grounded theory and defines it as “imagining all possible theoretical explanations for the puzzling observations and then testing the explanations in experience against new empirical data.” (p 38). To aid this process the development of a constant comparison technique (Weed, 2017) is needed which will include consistently comparing that which is generated with other codes, other empirical work or other knowledge identified by theoretical sampling. Confidence in the ideas created is developed by using constant comparison (Charmaz, 2017). Consider preconceived ideas or theory carefully, each pre-conceived idea should earn its way into the analysis (Charmaz, 2006). When considering past ideas or theory consider if these concepts help you understand your data and how they fit different aspects. Is interpretation possible without this understanding? If they are needed why?

- Specific questions can also aid this process. The questions are adapted from Charmaz (2021) and focus on your own questions: What codes provide the best account for the data? What direction does this take you in? can you make further comparisons between codes? Does anything appear missing?

- The meta-ethnographer should create defendable findings by showing how the ideas are supported by the studies included and achieve the concept of resonance. The concept of resonance is that the concepts and ideas generated give insight to others beyond their own area of interest (Charmaz, 2006; 2014)

- Further searching can be undertaken which continues and works with new idea development and stops at the point of theoretical sampling in a similar way to social constructivist grounded theory (Charmaz, 2021). Searching should consider and answer the following questions (Soundy & Heneghan, 2022): What articles provide the greatest insight or challenge to the idea generated? What other types or articles or research are needed? This should include articles that consider concepts related to the idea, past models, or theories (Soundy & Heneghan, 2022).

Phase 5: Expression of the theory, model or process

- Findings should be expressed as a discipline specific theory, model or process (Soundy and Henghan, 2022). The expression should be accessible for different audiences, and it needs to be accessible for policy makers and for practitioners (France et al., 2019a). Charmaz (2006; 2014) supports this as an outcome for grounded theory and suggests the expression can also create new lines of research as well as revealing pervasive processes and practice.

- The discussion section should include a summary of findings as well as identify strengths and weaknesses, reflexivity, and recommendations (France et al., 2019a; Sattar et al., 2021). It should also provide consideration and limitations in particular around the extent to which recognition of the cultural context has been considered (France et al., 2019b) or critical inquiry established.

Discussion

Limitations

Conclusion

- Supplementary online material: None.

- Funding details: No funded was provided for this research.

- Disclosure statement: The author reports there are no competing interests to declare.

- Data deposition: Not applicable.

References

- Ahrens, A., Zaščerinska, J. (2014). Factors that influence sample size in educational research. Education in a Changing Society. [CrossRef]

- Alemu, G., Stevens, B., Ross, P., Chandler, J. (2015). The use of a constructivist grounded theory method to explore the role of socially-constructed metadata (web 2.0) approaches. Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Libraries (QQML), 4: 517-540.

- Atkins, S., Lewin, S., Smith, H., Engel, M., Fretheim, A., & Volmink, J. (2008) Conducting a meta-ethnography of qualitative literature: lessons learnt. BMC Medical Research Methodology 8: 1-10.

- Bell, Z., Scott, S., Visram, S., Rankin, J., Bambra, C., Heslehurst, N. (2022). Experiences and perceptions of nutritional health and wellbeing amongst food insecure women in Europe: A qualitative meta-ethnography. Social Science and Medicine, 311; 115313.

- Britten, N., Campbell, R., Pope, C., Donovan, J., Morgan, M., Pill, R. (2002) Using meta ethnography to synthesise qualitative research: a worked example. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 7: 209-215.

- Buckley, C. A., & Warig (2013). Using diagrams to support the research process: examples from grounded theory. Qualitative Research, 13: 148-172.

- Cahill, M., Robinson, K., Pettigrew, J., Galvin, R., Stanley, M. (2018). Qualitative synthesis: A guide to conducting a meta-ethnography. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 81; 129-137.

- Campbell, R., Pound, P., Morgan, M., Daker-White, G., Britten, N., Pill, R., et al. (2011) Evaluating meta-ethnography: systematic analysis and synthesis of qualitative research. Health Technology Assessment, 15; 1-64.

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage.

- Charmaz K. (2012). The power and potential of grounded theory. Medical Sociology Online, 6: 2-15.

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory. 2nd Ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Charmaz K. (2017). The power of constructivist grounded theory for critical inquiry. Qualitive Inquiry, 23; 34-45.

- Charmaz, K. (2021). Chapter 8. The genesis, grounds, and growth of constructivist grounded theory. In J. M. Morse., Bowers, B. J., Charmaz, K., Clarke, A. E., Cobin, J., Poor, C. J., Stern, P. N. (Eds.). Developing grounded theory the second generation revisited (2nd edition). Routledge.

- Charmaz, K., Belgrave, L. L. (2019). Thinking about data with grounded theory. Qualitative Inquiry, 25: 743-753.

- Charmaz, K., Thornberg, R. (2021). The pursuit of quality in grounded theory. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18; 305-327.

- Cunningham, M., France, E. F., Ring, N., Uny, I., Duncan, E. A. S., Roberts, R. J. (2019). Developing a reporting guideline to improve meta-ethnography in health research: the eMERGe mixed methods study. Health Services and Delivery Research, NIHR Journal Library.

- Doyle, L. H. (2003) Synthesis through meta-ethnography: paradoxes, enhancements and possibilities. Qualitative Research 3(3): 321-44.

- Dixon-Woods, M., Kirk, D., Agarwal, S., Annandale, E., Arthur, A., Harvey, J., Hsu, R., et al. (2005). Vulnerable groups and access to health care: a critical interpretive review. Report for the National Co-ordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation R & D (NCCSDO).

- Eaves, Y. D. (2001). A synthesis technique for grounded theory data analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 35: 654-663.

- Everhart, N., Johnston, M. P. (2017). Meta-ethnography and its potential for theory building in library and information science. Library and Information Research, 41; 32-44.

- Fassinger, R. E. (2005). Paradigms, praxis, problems, and promise: Grounded theory in counselling psychology research. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52; 156–166.

- Finfgeld, D. J. (1999). Courage as a process of pushing beyond the struggle. Qualitative Health Research, 9: 803-814.

- Firestone, W. A. (1993). Alternative arguments for generalising from data as applied to qualitative research. Educational Researcher, 22: 16-23.

- France, E. F., Uny, I., Ring, N., Turley, R. L., Maxwell, M., Duncan, E. A. S et al., (2019a). A methodological systematic review of meta-ethnography conduct to articulate the complex analytical processes. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19; 35.

- France, E. F., Uny, I., Ring, N., Turley, R., Maxwell, M., Duncan, E. A. S et al. (2019b). A methodological systematic review of meta-ethnography conduct to articulate the complex analytical phases. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19: 35.

- Grant, M. J., Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26; 91-108.

- Hernández-Hernández, F., & Sancho-Gil, J. M. (2017). Using meta-ethnographic analysis to understanding and represent youth’s notions and experiences in and out of secondary school. Ethnography and Education, 12(2), 178–193.

- Hutchison, A. J., Johnston, L., Breckon, J. (2011): Grounded Theory Based Research within Exercise Psychology: A Critical Review, Qualitative Research in Psychology, 8:3, 247-272.

- Johansson, CB. (2019). Introduction to qualitative research and grounded theory. International Body Psychotherapy Journal, 18: 94-99.

- Kearney, M. H. (2001). Enduring love: a grounded form theory of women’s experience of domestic violence, Research Nursing and Health, 24: 270-282.

- Kim, B. (2001). Social constructivism. In M. Orey (Ed.), Emerging perspectives on learning, teaching, and technology. Available from Website: http://www.coe.uga.edu/epltt/SocialConstructivism.htm.

- Lee, R. P., Hart, R. I., Watson, R. M., Rapley, T. (2015). Qualitative synthesis in practice: some pragmatics of meta-ethnography. Qualitative Research, 15; 334-350.

- Liu, C. H. , Matthews, R. (2005). Vygotsky’s philosophy: Constructivism and its criticism examined. International Education Journal, 6(3), 386-399.

- Mills, J. , Bonner, A., Francis, K. (2006). The development of constructivist grounded theory. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5; 25-35.

- Mohajan, D., Mohajan, H. K. (2022). Constructivist grounded theory: A new research approach in social science. Research Advances in Education, 1: 8-14.

- Morse, J., Clark, L. (2019). The nuances of grounded theory sampling and the pivotal role of theoretical sampling. In A. Bryant, K Charmaz (Eds). Sage handbook of current developments in grounded theory. London: Sage.

- Noblit, G. W. & Hare, R. D. (1988) Meta-ethnography: Synthesising Qualitative Studies. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2020). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. British Medical Journal, 202.

- Popay, J., Roberts, H., Sowden, A., Petticrew, M., Arai, L., Rodgers, M. et al. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A produce from the ESRC methods programme. Lancaster University Press. Lancaster UK.

- Pound, P., Britten, N., Morgan, M., Yardley, L., Pope, C., Daker-White, G. et al. (2005) Resisting medicines: a synthesis of qualitative studies of medicine taking. Social Science & Medicine, 61: 133-55.

- Polit, D. F., Beck, C. T. (2010). Generalization in quantitative and qualitative research: Myths and strategies. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 47; 1451-1458.

- Rice, E. H. (2002) The collaboration process in professional development schools: results of a meta-ethnography, 1990-1998. Journal of Teacher Education 53: 55-67.

- Sattar, R., Lawton, R., Panagioti, M., Johnson, J. (2021). Meta-ethnography in healthcare research: a guide to using a meta-ethnographic approach for literature synthesis. BMC Medical Services Research, 21:50.

- Sellevold, V. L., Hamre, L. L., Bondas, T. E. (2022). A meta-ethnography of language challenges in midwifery care. European Journal of Midwifery, 6; 41.

- Sveen, S., Anthun, K. S., Batt-Rawden, K. B., Tingvold, L. (2022). Immigrants’ experiences of volunteering; a meta-ethnography. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 52:569-588.

- Strauss, A., Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA, Sage.

- Sutton, A., Clowes, M., Preston, L., Booth, A. (2019). Meeting the review family: exploring review types and associated information retrieval requirements. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 36: 202-222.

- Toye, F., Seers, K., Allcock, N., Briggs, M., Carr, E., & Barker, K. (2014). Meta-ethnography 25 years on: Challenges and insights for synthesising a large number of qualitative studies. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 14: 80.

- Toye, F., Seers, K., Allcock, N., Briggs, M., Carr, E., Andrews, J et al. (2013) ‘Trying to pin down jelly’ – Exploring intuitive processes in quality assessment for meta-ethnography. BMC Medical Research Methodology 13: 46. [CrossRef]

- Thorne S (2017) Metasynthetic madness: What kind of monster have we created? Qualitative Health Research, 27: 3–12.

- Thornberg R. (2012). Informed grounded theory. Scandinavian Journal of Education, 56: 243-259.

- Tie, Y. C., Birks, M., Francis, K. (2019). Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers. Sage Open Medicine, 7: 1-8.

- Weed M. (2017). Capturing the essence of grounded theory: the importance of understanding commonalities and variants, Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 9:1, 149-156.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).