Submitted:

19 June 2023

Posted:

20 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Data Results, and Data Collection

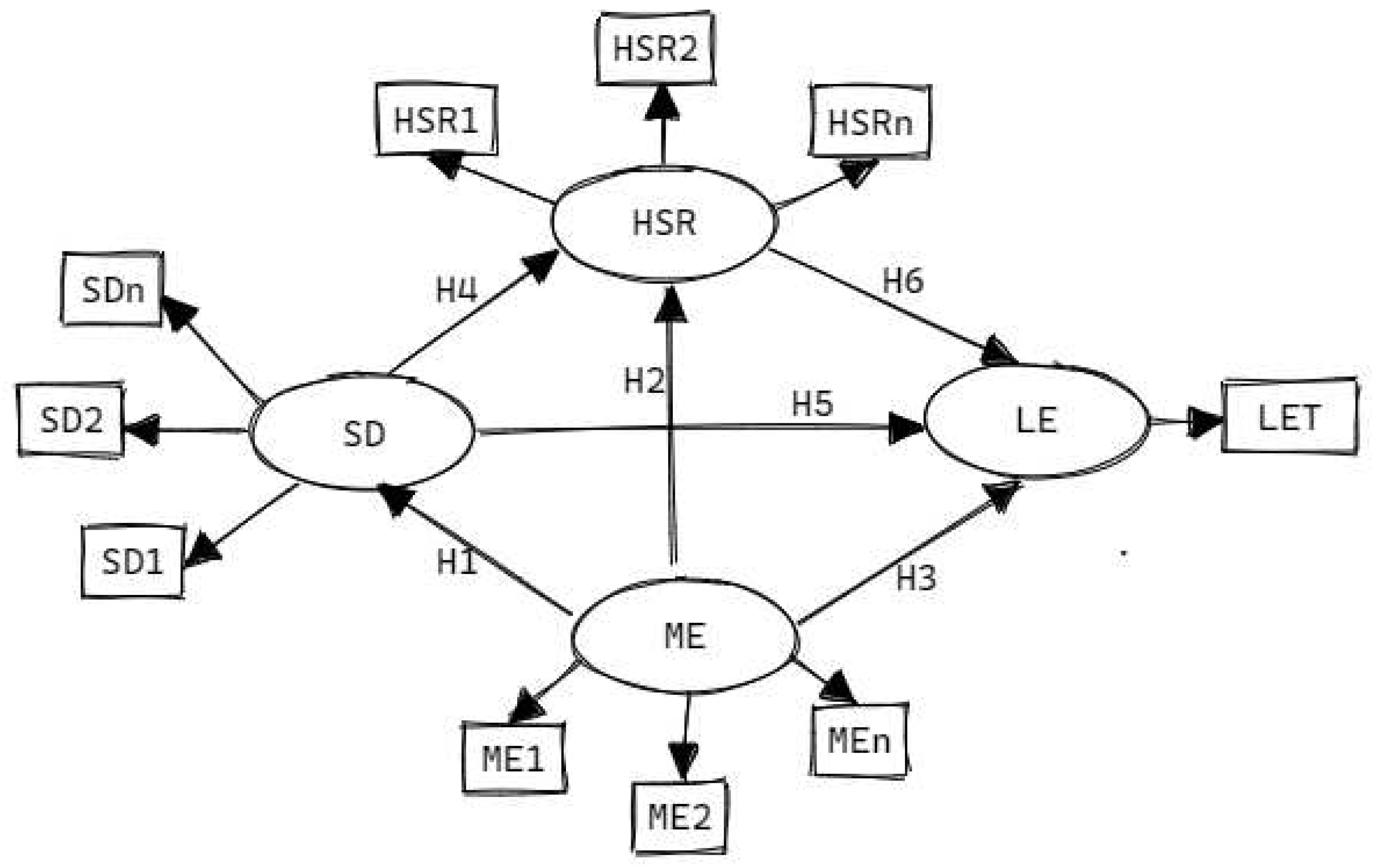

2.2. The Conceptual Model and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

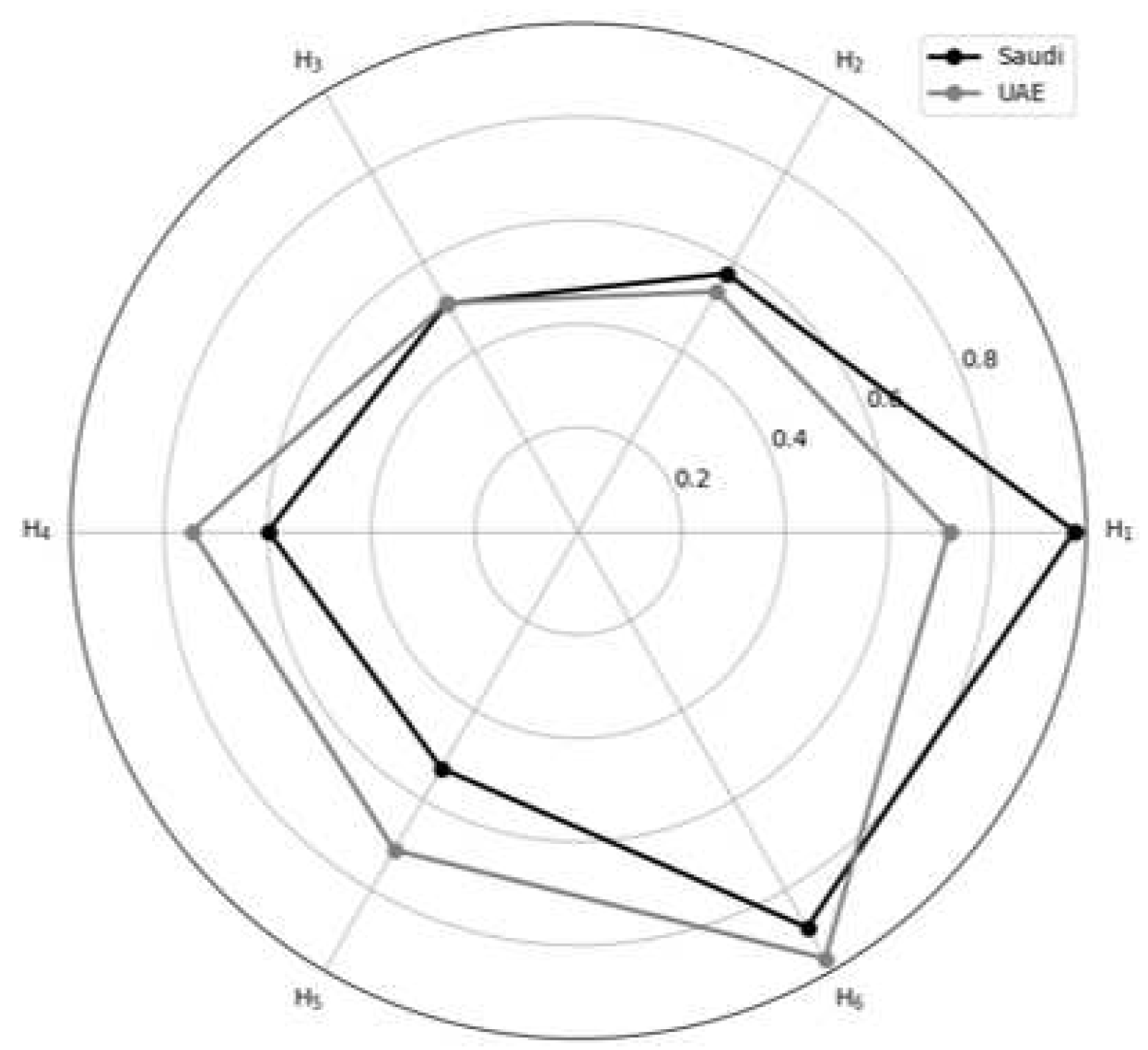

4.1. Comparison between the Two Models

4.2. Limitations of this Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guénette, J. D., Kose, M. A., & Sugawara, N. (2022). Is a Global Recession Imminent? Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4223901 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4223901. [CrossRef]

- Ho, J. Y., & Hendi, A. S. (2018). Recent trends in life expectancy across high income countries: retrospective observational study. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 362, k2562. [CrossRef]

- Roser, M., Ortiz-Ospina, E., & Ritchie, H. (2013). Life Expectancy. Our World in Data. Available online https://ourworldindata.org/life-expectancy.

- Braveman, P., & Gottlieb, L. (2014). The social determinants of health: it's time to consider the causes of the causes. Public health reports, 129(1_suppl2), 19-31.

- Mikkonen, J., Social determinants of health, Canadian Electronic Library. Canada. 2010. Available online: https://policycommons.net/artifacts/1204147/social-determinants-of-health/1757256/ on 18 Jun 2023. CID: 20.500.12592/mm0nz9.

- Wirayuda, A. A. B., & Chan, M. F. (2021). A Systematic Review of Sociodemographic, Macroeconomic, and Health Resources Factors on Life Expectancy. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health, 33(4), 335-356. 4. [CrossRef]

- Heuveline, P. (2022). Global and National Declines in Life Expectancy: An End-of-2021 Assessment. Population and Development Review, 48(1), 31-50. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Mortality and global health estimates. Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates.

- OECD. (2019). OECD Economic Surveys: United States 2019. OECD Publishing. [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2021). Home. Health at a Glance 2021 : OECD Indicators | OECD iLibrary. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/e0d509f9-en/index.html?itemId=%2Fcontent%2Fcomponent%2Fe0d509f9-en.

- Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. (2023, January 13). Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) | History, Member Countries, Purpose, & Summits. Encyclopedia Britannica. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Gulf-Cooperation-Council. 13 January.

- The National News. (2023, June 13). UAE and Saudi Arabia drive GCC's 'significant improvement' in economic diversification. Available online: https://www.thenationalnews.com/business/2023/06/13/uae-and-saudi-arabia-drive-gccs-significant-improvement-in-economic-diversification/. 13 June.

- Macrotrends. (2023). Saudi Arabia Life Expectancy 1950-2022. Available online: https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/SAU/saudi-arabia/life-expectancy (access on 1 June 2023).

- Statista. (2023). Share of gross domestic product expenditures on healthcare in the Gulf Cooperation Council from in 2019, by country. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/672429/gcc-share-of-gdp-spending-on-health-sector-by-country/.

- Statista. (2022). Life expectancy at birth in the United Arab Emirates from 2000 to 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/297160/uae-life-expectancy/.

- World Health Organization. Health inequities and their causes. Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/facts-in-pictures/detail/health-inequities-and-their-causes.

- Mattke, S., Hunter, L. E., Magnuson, M., & Arifkhanova, A. (2015). Population health management and the second Golden age of Arab medicine: promoting health, localizing knowledge industries, and diversifying economies in the GCC countries. Rand Health Quarterly, 5(1), 3. [CrossRef]

- Fromkin, D. (1991). How the modern Middle East map came to be drawn. Smithsonian, 22(2), 132-146.

- Rogan, E. L. (2019). The emergence of the Middle East into the modern state system. International Relations of the Middle East, 5th ed, Chapter 2. 17-38. Politics Trove. [CrossRef]

- Callen, M. T., Cherif, R., Hasanov, F., Hegazy, M. A., & Khandelwal, P. (2014). Economic diversification in the GCC: Past, present, and future. International Monetary Fund. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/sdn/2014/sdn1412.pdf.

- Wilson, R. (2021) Economic development in the Middle East. Routledge.

- Goldschmidt, A., & Boum, A. (2018) A concise history of the Middle East. Routledge.

- Torstrick, R. & Faier, E. (2009). Culture and Customs of the Arab Gulf States. Available online: http://publisher.abc-clio.com/EGR3659.

- Rajan, S. I. (2018). Demography of the Gulf region. In South Asian migration in the Gulf (pp. 35-59). Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

- Alrouh, H., Ismail, A., & Cheema, S. (2013). Demographic and health indicators in Gulf Cooperation Council nations with an emphasis on UAE. Journal of Local and Global Health Perspectives, 2013(1), 3. [CrossRef]

- Ben Hassen, T. (2022). The GCC Economies in the Wake of COVID-19: Toward Post-Oil Sustainable Knowledge-Based Economies? Sustainability, 14(18), 11251. [CrossRef]

- Abouzzohour, Y. (2021). One Year into His Reign, Saudi’s Sultan Must Renegotiate the Social Contract and Prioritize Diversification. Brookings Institution, January 13. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2021/01/13/one-year-into-his-reign-omans-sultan-must-renegotiate-the-social-contract-and-prioritize-diversification/ (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- Besta, S. (2019, October 11). Top Five countries with the largest oil reserves in the Middle East. NS Energy. Available online: https://www.nsenergybusiness.com/features/countries-oil-reserves-middle-east/ (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- World Health Organization. GHE: Life expectancy and healthy life expectancy. Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-healthestimates/ghe-life-expectancy-and-healthy-life-expectancy.

- Miladinov, G. (2020). Socioeconomic development and life expectancy relationship: evidence from the EU accession candidate countries. Genus. 76(1), 2. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S. A., & Afzal, M. N. I. (2022). Sectoral diversification of UAE toward a knowledge-based economy. Review of Economics and Political Science. 7(3), 177-193. [CrossRef]

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. (2022). World Investment Report 2022. UNCTAD. TD/63/Rev.2. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/td63rev2_en.pdf.

- Gulf News. (2011, November 28). Diversification raises non-oil share of UAE’s GDP to 71%. https://gulfnews.com/business/diversification-raises-non-oil-share-of-uaes-gdp-to-71-1.795268. 28 November.

- Gulf News. (2023, December 6). UAE healthcare sector in top shape. https://gulfnews.com/uae/health/uae-healthcare-sector-in-top-shape-1.1638787939625.

- The Borgen Project. (2020, July 29). Economic diversification in Saudi Arabia. https://borgenproject.org/economic-diversification-in-saudi-arabia/. 29 July.

- Al Naimi, S. M. (2021). Economic diversification trends in the Gulf: the case of Saudi Arabia. Circular Economy and Sustainability, 2(4), 221-230. [CrossRef]

- Bah, S. (2018). How feasible is the life expectancy target in the Saudi Arabian vision for 2030. East Mediterr Health J, 24(4), 401-404. [CrossRef]

- Koornneef, E., Robben, P., & Blair, I. (2017). Progress and outcomes of health systems reform in the United Arab Emirates: a systematic review. BMC health services research, 17, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- The Official Portal of the UAE Government. Population and demographic mix. 2022. Available online: https://u.ae/en/information-and-services/social-affairs/preserving-the-emirati-national-identity/population-and-demographic-mix (Access 18 Oct 2022).

- Chen, Z., Ma, Y., Hua, J., Wang, Y., & Guo, H. (2021). Impacts from economic development and environmental factors on life expectancy: A comparative study based on data from both developed and developing countries from 2004 to 2016. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8559. [CrossRef]

- The Official Portal of the UAE Government. Environment and climate change. 7 Feb 2023 Retrieved June 4, 2023, Available online: https://www.moccae.gov.ae/en/home.aspx (Access on 4 June 2023).

- Ministry of Environment, Water and Agriculture. (2023). Environmental protection in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. https://www.my.gov.sa/wps/portal/snp/aboutksa/environmentalProtection/.

- World Health Organization. (2022a). Environmental health Saudi Arabia 2022 country profile. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/environmental-health-sau-2022-country-profile.

- Roffia, P., Bucciol, A., & Hashlamoun, S. (2023). Determinants of life expectancy at birth: a longitudinal study on OECD countries. International Journal of Health Economics and Management, 23(2), 189-212. [CrossRef]

- Wirayuda, A. A. B., Al-Mahrezi, A., & Chan, M. F. (2023). Factors Impacting Life Expectancy in Bahrain: Evidence from 1971 to 2020 Data. International Journal of Social Determinants of Health and Health Services, 53(1), 74-84. [CrossRef]

- Gulf Business. (2016, September 10). Revealed: 7 stats on the UAE’s healthcare and health insurance market. https://gulfbusiness.com/revealed-7-stats-uaes-healthcare-health-insurance-market/. 10 September.

- Al Saffer, Q., Al-Ghaith, T., Alshehri, A., Al-Mohammed, R., Al Homidi, S., Hamza, M. M., Herbst, C. H., & Alazemi, N. (2021). The capacity of primary health care facilities in Saudi Arabia: infrastructure, services, drug availability, and human resources. BMC Health Services Research, 21(365). [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2021). Life expectancy at birth. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/life-expectancy-at-birth-(years).

- Worldometer. (2022). Life expectancy by country and in the world (2023). https://www.worldometers.info/demographics/life-expectancy/.

- Cutler, D., Deaton, A., & Lleras-Muney, A. (2006). The determinants of mortality. Journal of economic perspectives, 20(3), 97-120. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Non-communicable diseases. 16 September 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases. 16 September.

- Wirayuda, A. A. B., Jaju, S., Alsaidi, Y., & Chan, M. F. (2022). A structural equation model to explore sociodemographic, macroeconomic, and health factors affecting life expectancy in Oman. The Pan African Medical Journal, 41.

- World Bank. Saudi Arabia. 2023. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/country/SA (Accessed on 13 Jan 2023).

- World Bank. United Arab Emirates. 2023. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/country/AE (Accessed on 11 Jan. 2023).

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate Data Analysis. Andover. Hampshire, United Kingdom: Cengage.

- Hair Jr, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., & Ray, S. (2021). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R: A workbook.

- Zhang, Z. (2016). Multiple imputations for time series data with Amelia package. Annals of translational medicine, 4(3). [CrossRef]

- Chan, M. F., & Kamala Devi, M. (2015). Factors Affecting Life Expectancy: Evidence from 1980-2009 Data in Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailand. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health, 27(2). [CrossRef]

- Chin, W. W. (2010). How to write up and report PLS analyses. In Handbook of partial least squares (pp. 655-690). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

- Franke, G., & Sarstedt, M. (2019). Heuristics versus statistics in discriminant validity testing: a comparison of four procedures. Internet Research. [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of marketing science, 43(1), 115-135. [CrossRef]

- Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. (2023, March 13). Causal mediation. Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. Available online: https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/research/population-health-methods/causal-mediation.

- Kim, J. I., & Kim, G. (2018). Effects on inequality in life expectancy from a social ecology perspective. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Mondal, M. N. I., & Shitan, M. (2014). Relative importance of demographic, socioeconomic, and health factors on life expectancy in low-and lower-middle-income countries. Journal of Epidemiology, 24(2), 117-124. [CrossRef]

- Assadzadeh, A., & Nategh, H. (2015, November). The relationship between per capita electricity consumption and human development indices. In Proceedings of 6th IASTEM International Conference (pp. 1-7).

- Pasten, C., & Santamarina, J. C. (2012). Energy and quality of life. Energy Policy, 49, 468-476. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A. Z. E. (2015). The role of diversification strategies in the economic development for oil-depended countries:-the case of UAE. International Journal of Business and Economic Development (IJBED), 3(1).

- Euromonitor International. Economic growth and life expectancy: Do wealthier countries live longer? 24 Oct. 2019. Available online: https://www.euromonitor.com/article/economic-growth-and-life-expectancy-do-wealthier-countries-live-longer.

- Guo, J. The relationship between GDP and life expectancy isn’t as simple as you might think. The Washington Post. 18 Oct 2016. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/10/the-relationship-between-gdp-and-life-expectancy-isnt-as-simple-as-you-might-think.

- Kunze, L. (2014). Life expectancy and economic growth. Journal of Macroeconomics, 39, 54-65. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Asghar, M. M., Zaidi, S. A. H., Nawaz, K., Wang, B., Zhao, W., & Xu, F. (2020). The dynamic relationship between economic growth and life expectancy: Contradictory role of energy consumption and financial development in Pakistan. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 53, 257-266. [CrossRef]

- McKinsey & Company. Prioritizing health: A prescription for prosperity. 2020. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare/our-insights/prioritizing-health-a-prescription-for-prosperity (Accessed on 12 Jan 2023).

- Luy, M., Di Giulio, P., Di Lego, V., Lazarevič, P., & Sauerberg, M. (2020). Life expectancy: frequently used but hardly understood. Gerontology, 66(1), 95-104. [CrossRef]

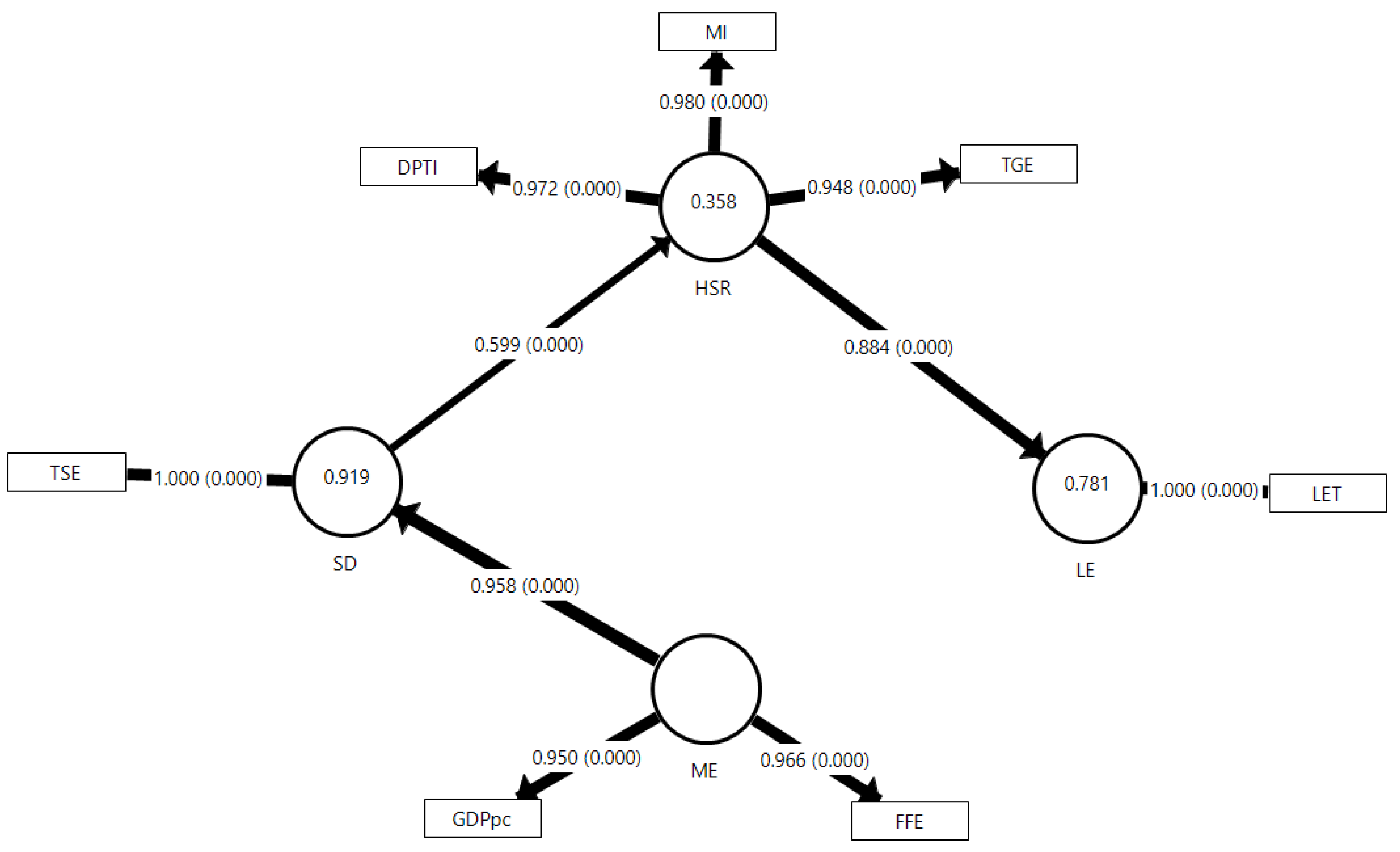

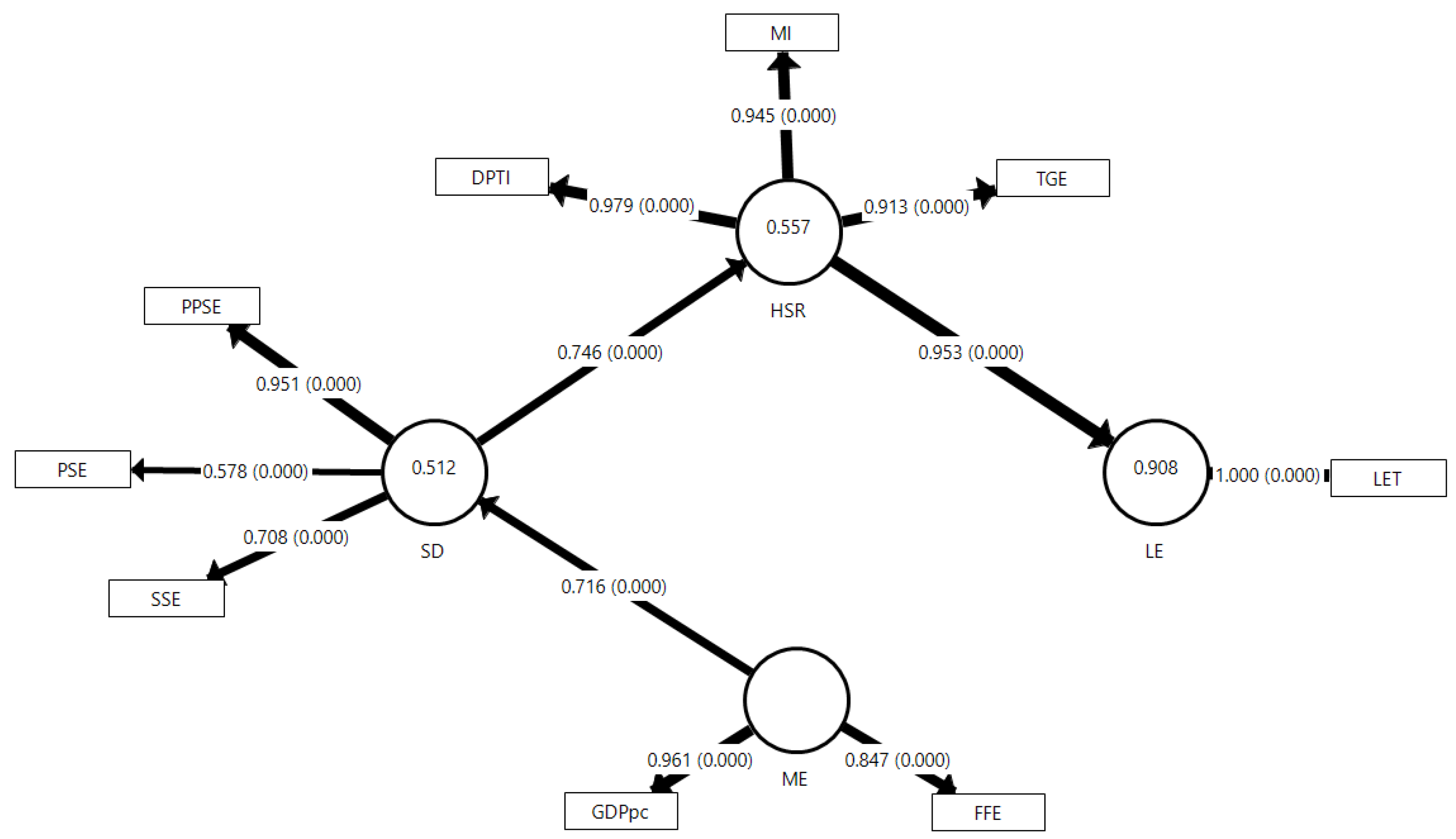

| LV | MV | Abbreviation | Indicator (Unit) | Loading | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saudi | UAE | ||||

| LE | LET | Life Expectancy in Total | Life expectancy at birth, total (years) | 1.000* | 1.000* |

| ME | GDPpc | GDP per capita | GDP per capita (Local Currency Unit) | 0.950* | 0.961* |

| FFE | Fossil Fuel Electricity | Fossil fuels electricity generation ( billion kilo-watthours) | 0.966* | - | |

| Electricity production from natural gas sources (%) | - | 0.847* | |||

| SD | PPSE | Pre-Primary School Enrollment | School enrollment, pre-primary (% gross) | - | 0.951* |

| PSE | Primary School Enrollment | School enrollment, primary (% gross) | - | 0.578* | |

| SSE | Secondary School Enrollment | School enrollment, secondary (% gross) | - | 0.708* | |

| TSE | Tertiary School Enrollment | School enrollment, tertiary (% gross) | 1.000 | - | |

| HSR | DPTI | Diphtheria, Pertussis, and Tetanus (DPT) Immunization | Immunization, DPT (% of children ages 12-23 months) | 0.972* | 0.979* |

| MI | Measles Immunization | Immunization, measles (% of children ages 12-23 months) | 0.980* | 0.945* | |

| TGE | Total Greenhouse Emission | Total greenhouse gas emissions (kilotons of CO2) | 0.948* | 0.913* | |

| LV | Country | CA | CR | Rhô-A | AVE | Q² | R² | HTMT (95%CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ME | SD | HSR | ||||||||

| ME | Saudi | 0.930 | 0.952 | 0.957 | 0.775 | - | - | - | - | - |

| UAE | 0.800 | 0.901 | 0.914 | 0.734 | - | - | ||||

| SD | Saudi | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.590 | 0.919 | 0.668 (0.258-0.983) | - | - |

| UAE | 0.644 | 0.799 | 0.953 | 0.523 | 0.740 | 0.512 | 0.783 (0.573-0.960) | - | ||

| HSR | Saudi | 0.965 | 0.977 | 0.972 | 0.934 | 0.640 | 0.358 | 0.800 (0.702-0.988) | 0.524 (0.274-0.803) | - |

| UAE | 0.952 | 0.965 | 0.943 | 0.843 | 0.720 | 0.557 | 0.847 (0.723-0.955) | 0.822 (0.633-0.981) | ||

| LE | Saudi | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.864 | 0.781 | 0.921 (0.821-0.975) | 0.656 (0.293-0.913) | 0.898 (0.852-0.964) |

| UAE | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.969 | 0.908 | 0.933 (0.849-0.993) | 0.978 (0.945-0.998) | 0.972 (0.946-0.990) | |

| Hypothesis (Relationship) | Country | Direct Effect (95% CI) |

Indirect Effect (95% CI) |

Total Effect (95%CI) |

f² |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 (ME→ SD) | Saudi | 0.958 (0.943-0.972) | - | 0.958 (0.943-0.972) | 11.293 |

| UAE | 0.716 (0.625-0.779) | 0.716 (0.625-0.779) | 1.051 | ||

| H2 (ME→ HSR) | Saudi | - | 0.574 (0.495-0.648) | 0.574 (0.495-0.648) | - |

| UAE | - | 0.534 (0.434-0.603) | 0.534 (0.434-0.603) | - | |

| H3 (ME→ LE) | Saudi | - | 0.507 (0.415-0.590) | 0.507 (0.415-0.590) | - |

| UAE | - | 0.509 (0.411-0.576) | 0.509 (0.411-0.576) | - | |

| H4 (SD→ HSR) | Saudi | 0.599 (0.517-0.674) | - | 0.599 (0.517-0.674) | 0.559 |

| UAE | 0.746 (0.627-0.823) | 0.746 (0.627-0.823) | 1.256 | ||

| H5 (SD→ LE) | Saudi | - | 0.529 (0.432-0.614) | 0.529 (0.432-0.614) | - |

| UAE | - | 0.711 (0.590-0.793) | 0.711 (0.590-0.793) | - | |

| H6 (HSR→ LE) | Saudi | 0.884 (0.815-0.923) | - | 0.884 (0.815-0.923) | 3.558 |

| UAE | 0.953 (0.928-0.970) | 0.953 (0.928-0.970) | 9.870 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).