Submitted:

20 June 2023

Posted:

20 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Location and sampling

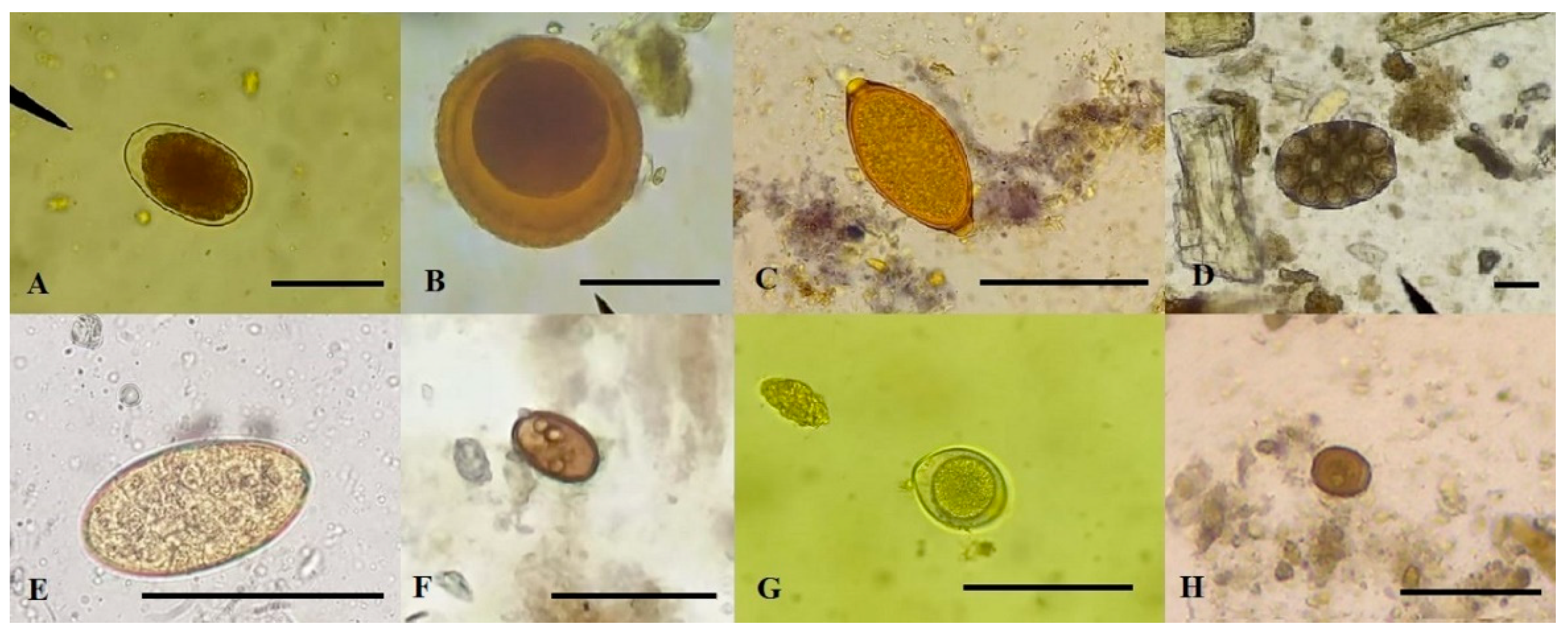

2.2. Coproparasitological examination

2.3. Data analysis and interpretation

2.4. Cats

2.5. Ethics Committee

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence and richness of parasites in dogs

3.2. Risk factors

3.3. Comparison of techniques

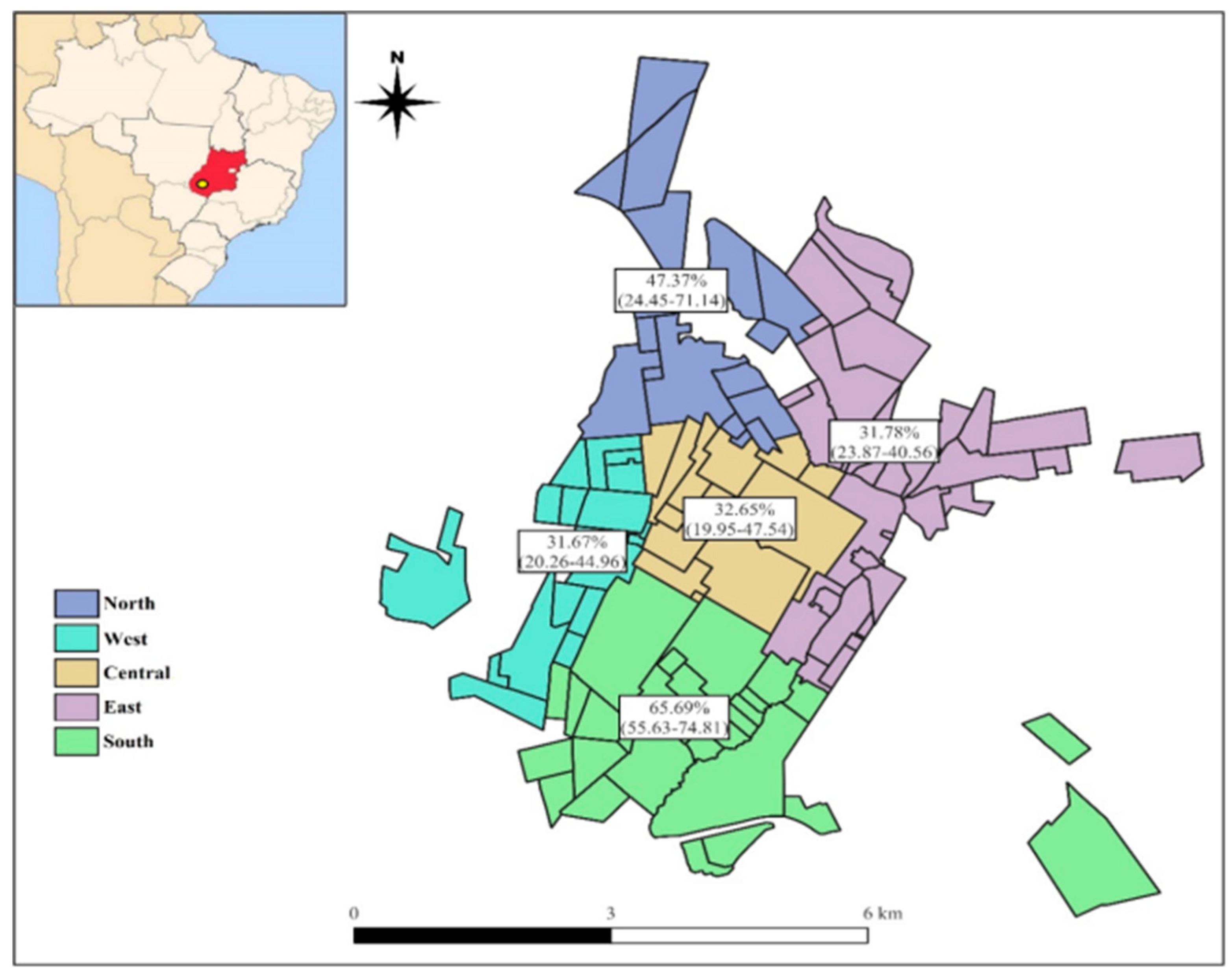

3.4. Spatial distribution

3.5. Cats

4. Discussion

4.1. Control and prevention

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Giumelli, R.D.; Santos, M.C.P. Convivência com animais de estimação: um estudo fenomenológico. Rev. Abordagem Gestalt. 2016, 22, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajero, O.T.; Janousková, E.; Bakare, E.A.; Belizario, V.; Divina, B.; Alonte, A.J.; Manalo, S.M.; Paller, V.G.; Betson, M.; Prada, J.M. Co-infection of intestinal helminths in humans and animals in the Philippines. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2022, 116, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capuano, D.M.; Rocha, G.M. Ocorrência de parasitas com potencial zoonótico em fezes de cães coletadas em áreas públicas do município de Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brasil. Rev. Bras. Epidemiol. 2006, 9, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoletti, B.; Traversa, D.; Lorio, R.; Berardinis, A.; Bartolini, R.; Salini, R.; Cesare, A. Zoonotic parasites in feces and fur of stray and private dogs from Italy. Parasitol. Res. 2015, 114, 2135–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojar, H.; Kłapeć, T. Contamination of selected recreational areas in Lublin Province, Eastern Poland, by eggs of Toxocara spp., Ancylostoma spp. and Trichuris spp. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2018, 25, 460–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, D.B.; Guimarães, D.R.A.; Souza, M.A.A. Contaminação parasitológica do solo em parques públicos da cidade de Conceição da Barra, Espírito Santo, Brasil. Health Bioscienc. 2021, 2, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil, Ministério da Saúde. Textbook of Guia Prático para o Controle das Geo-helmintíases; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, DF, Brazil, 2022; 33p. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, J.I.G.S.; Pena, H.F.J.; Azevedo, S.S.; Labruna, M.B.; Gennari, S.M. Occurrences of gastrointestinal parasites in fecal samples from domestic dogs in São Paulo, SP, Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2016, 25, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, M.F.; Ramos, R.A.N.; Calado, A.M.C.; Lima, V.F.S.; Ramos, I.C.N.; Tenório, R.F.L.; Faustino, M.A.G.; Alves, L.C. Gastrointestinal parasites of cats in Brazil: frequency and zoonotic risk. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2016, 25, 254–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pumidonming, W.; Salman, D.; Gronsang, D.; Abdelbaset, A.E.; Sangkaeo, K.; Kawaso, S.; Igarashi, M. Prevalence of gastrointestinal helminth parasites of zoonotic significance in dogs and cats in lower Northern Thailand. J. Vet. Med. Scienc. 2017, 78, 1779–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.F.; Barbosa, A.S.; Moura, A.P.P.; Vasconcellos, M.L.; Uchôa, C.M.A.; Bastos, O.M.P.; Amendoeira, M.R.R. Gastrointestinal parasites in stray and shelter cats in the municipality of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2017, 26, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauda, F.; Malandrucco, L.; De Liberato, C.; Perrucci, S. Gastrointestinal parasites in shelter cats of central Italy. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Reports 2019, 18, e100321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, V.F.; Oliveira, N.M.S.; Silva, B.C.M.; Marques, M.J.; Darcadia, H.P.; Nogueira, D.A. Prevalence of zoonotic intestinal parasites in domiciled dogs living in the urban area of Alfenas, State of Minas Gerais, Brazil. Ann. Parasitol. 2020, 66, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arruda, I.F.; Ramos, R.C.F.; Barbosa, A.S.; Abboud, L.C.S.; Reis, I.C.; Millar, P.R.; Amendoeira, M.R.R. Intestinal parasites and risk factors in dogs and cats from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Reports 2021, 24, e100552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamani, J.; Massetti, L.; Olubade, T.; Balami, J.A.; Samdi, K.M.; Traub, R.J.; Colella, V.; González-Miguel, J. Canine gastrointestinal parasites as a potential source of zoonotic infections in Nigeria: A nationwide survey. Prev. Vet. Med. 2021, 192, e105385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi-Storm, N.; Mejer, H.; Al-Sabi, M.N.S.; Olsen, C.S.; Thamsborg, S.M.; Enemark, H.L. Gastrointestinal parasites of cats in Denmark assessed by necropsy and concentration McMaster technique. Vet. Parasitol. 2015, 214, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagamori, Y.; Payton, M.E.; Duncan-Decocq, R.; Johnson, E.M. Fecal survey of parasites in free-roaming cats in northcentral Oklahoma, United States. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Reports 2018, 14, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.A; Coop, R.L.; Wall, R.L. Textbook of Veterinary Parasitology; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; 1006 p. [Google Scholar]

- Hackett, T.; Lappin, M.R. Prevalence of enteric pathogens in dogs of north-central Colorado. J. Am. An. Hosp. Assoc. 2003, 39, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barutzki, D.; Schaper, R. Endoparasites in dogs and cats in Germany 1999-2002. Parasitol. Res. 2003, 90, S148–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinosa, H.S.; Górniak, S.L.; Bernardi, M.M. Textbook of Farmacologia aplicada à medicina veterinária; Guanabara Koogan: Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil, 2022; 1040 p. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, D.D. Textbook of Georgis’ Parasitology for Veterinarians; Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020; 2057 p. [Google Scholar]

- Kopp, S.R.; Kotze, A.C.; McCarthy, J.S.; Coleman, G.T. High-level pyrantel resistance in the hookworm Ancylostoma caninum. Vet. Parasitol. 2007, 143, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwath, M.L.; Robinson, D.R.; Katner, H.P. A presumptive case of toxocariasis associated with eosinophilic pleural effusion: case report and literature review. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2004, 71, 764. [Google Scholar]

- Foreyt, W.J. Textbook of Parasitologia veterinária: manual de referência; Roca: São Paulo, SP, Brazil, 2009; 238 p. [Google Scholar]

- Urquhart, G.M.; Armour, J.; Duncan, J.L.; Dunn, A.M.; Jennings, F.W. Textbook of Veterinary Parasitology; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, OX, UK, 1996; 396 p. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, S.G. Textbook Parasitologia na Medicina Veterinária; Roca: São Paulo, SP, Brazil, 2017; 370p. [Google Scholar]

- Felix, D.A.S.; Silva, C.X.; Gomes, J.S.; Dias, E.G.; Freitas, J.S.; Fernandes, L.E.S.; Mendes, T.M.; Farias, L.A. Toxocara spp., larva migrans visceral e saúde pública: Revisão. Pubvet 2020, 14, a719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, M.J.; Weber, D.M.; Costa, J.P. Prevalence of larva migrans in soils of city parks in Redenção, Pará State, Brazil. Rev. Pan-Amaz. Saude 2019, 10, e201901607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.P.; Duarte, R.B.; Silva, M.F.S.; Soares, J.M.; Braga, I.A.; Ramos, D.G.S. Occurrence of intestinal parasites in fecal samples of dogs and cats from Mineiros, Goiás. Ars Vet. 2022, 38, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, H. H. A simple levitation method for the detection of hookworm ova. Med. J. Aust. 1921, 18, 375–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, W.A.; Pons, J.A.; Janer, J.L. The sedimentation-concentration method in schistosomiasis mansoni. PR. J. Public Health Trop. Med. 1934, 9, 283–289. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, R.P. Textbook of Diagnóstico de Parasitismo Veterinário; Sulina: Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil, 1987; 156 p. [Google Scholar]

- Zajac, A.M.; Conboy, G.A. Textbook of Veterinary Clinical Parasitology; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, OX, UK, 2012; 368 p. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, A.O.; Lafferty, K.D.; Lotz, J.M.; Shostak, A.W. Parasitology meets ecology on its own terms: Margolis et al. revisited. J. Parasitol. 1997, 83, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guimarães, B.C.S.; Texeira, B.T.; Toledo, L.V.; Damasceno, L.S.; Almeida, M.E.W.C.; Martins, M.A.; Leite, N.S. Hookworm infection: Ancylostomiasis. Braz. J. Surg. Clin. Res. 2019, 26, 84–88. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, B.; Silva, A.N.F.; Mora, S.E.V.; Koslowski-Neto, V.A.; Justo, A.A.; Pantoja, J.C.F.; Schmidt, E.M.S.; Takahira, R.K. Epidemiological aspects of Ancylostoma spp. infection in naturally infected dogs from São Paulo state, Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Reports 2020, 22, e100452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, K.L.; Freitas, T.D.; Teixeira, M.C.; Araújo, F.A.P. Avaliação da ocorrência de formas parasitárias no solo de praças públicas no município de Esteio-RS. Rev. Acad. Ciênc. Agrár. Amb 2013, 11, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Prestes, L.F.; Jeske, S.; Santos, C.B.; Gallo, M.C.; Villela, M.M. Contaminação do solo por geohelmintos em áreas públicas de recreação em municípios do sul do Rio Grande do Sul (RS), Brasil. Rev. Patol. Trop. 2015, 44, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortes, E. Textbook of Parasitologia Veterinária; Ícone: São Paulo, SP, Brazil, 2017; 608 p. [Google Scholar]

- Francisco, M.M.S.; Silva, R.C.; Figueiredo, D.L.V.; Souza, J.N.; Ramalho, P.C.D.; Caetano, A.L. Prevalência de ovos e larvas de Ancylostoma spp. e de Toxocara spp. em praças públicas da cidade de Anápolis-GO. Ensaios Ciênc. C. Biol. Agrár. Saúde 2008, 12, 131–137. [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Filho, P.C.; Barros, L.M.; Campos, J.O.; Braga, V.B.; Cazorla, I.M.; Albuquerque, G.R.; Carvalho, S.M.S. Parasitas zoonóticos em fezes de cães em praças públicas do município de Itabuna, Bahia, Brasil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2008, 17, 206–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, J.R.R.; Mariano, Z.F.; Feltrin, J.C.; Silva, M.R. . O clima em cidade pequena: o sistema termodinâmico em Jataí (GO). Rev. Bras. Climatol. 2014, 15, 205–228. [Google Scholar]

- Dantas-Torres, F. Toxocara prevalence in dogs and cats in Brazil. Adv. Parasitol. 2020, 109, 715–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo, S.D.P.; Taddei, J.A.A.C.; Menezes, J.J.C.; Novo, N.F.; Silva, E.O.M.; Cristóvão, H.L.G.; Cury, M.C.F.S. Clinical-epidemiological study of toxocariasis in a pediatric population. J. Pediatr. 2005, 81, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradburya, R.S.; Hobbs, C.V. Toxocara seroprevalence in the USA and its impact for individuals and society. Adv. Parasitol. 2020, 109, 317–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidumayo, N.N. Prevalence of Toxocara in dogs and cats in Africa. Adv. Parasitol. 2020, 109, 861–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, A.; Pires, B.S.; Barwaldt, E.T.; Santos, E.M.; Dallmann, P.R.J.; Castro, T.A.; Nobre, M.O.; Nizoli, L.C. Trichuris vulpis eggs in stool samples of dogs analyzed in the region of Pelotas, RS, between 2015 and 2018. Rev. Acad. Ciênc. Anim. 2020, 18, e18004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acha, P.N; Szyfres, B. Textbook of Zoonosis y enfermidades transmisibles comunes al hombre ya los animales - Volume 3; Pan-American Health Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; 423 p. [Google Scholar]

- Longo, C.E.M.; Santos, G.R.; Oliveira, J.L.S.; Neves, M.F. Trichuris vulpis. Rev. Científ. Eletr. Med. Vet. 2008, 11, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Rey, L. Textbook of Parasitologia; Guanabara Koogan: Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil, 2013; 888 p. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, D.G.S.; Zocco, B.K.A.; Torres, M.M.; Braga, I.A.; Pacheco, R.C.; Sinkoc, A.F. Helminths parasites of stray dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) from Cuiabá, Midwestern of Brazil. Semina Ciênc. Agrar. 2015, 36, 889–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, S.P.; Silva, F.F.; Valêncio, B.A.; Carvalho, G.M.M.; Santos, A.; Costa, F.T.R.; Feitosa, T.F.; Vilela, V.L.R. Parasitos zoonóticos em solos de praças públicas no município de Sousa, Paraíba. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Vet. 2019, 26, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, A.; Evaristo, T.A.; Coelho, A.L.R.; Castro, T.A.; Mello, C.C.S.; Pappen, F.G.; Silva, S.S.; Nizoli, L.C. Presença de parasitos com potencial zoonótico na areia de praças de recreação de escolas municipais de educação infantil do munícipio de Pelotas, RS, Brasil. Vet. Zootec. 2019, 26, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, R.W.; Couto, C.G. Textbook of Medicina interna de pequenos animais; Guabara Koogan: Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil, 2015; 1512 p. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, D.G.S.; Santos, A.R.G.L.O.; Freitas, L.C.; Braga, I.A.; Silva, E.P.; Soares, L.M.C.; Antoniassi, N.A.B.; Furlan, F.H.; Pacheco, R.C. Feline platynosomiasis: analysis of the association of infection levels with pathological and biochemical findings. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2017, 26, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bielsa, L.M.; Greiner, E.C. Liver flukes (Platynosomum concinnum) in cats. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 1985, 21, 269–274. [Google Scholar]

- Ettinger, S.J.; Feldman, E.C. Textbook of Tratado de medicina interna veterinária; Manole: São Paulo, SP, Brazil, 1997; 1828 p. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, N.C.; Siqueira, D.F.; Perin, L.R.; Oliveira, L.C.; Campos, D.R.; Martins, I.V.F. Natural infection by Platynosomum fastosum in domestic feline in Alegre, Espírito Santo, Brazil and successful treatment with praziquantel. Med. Vet. UFRPE 2018, 12, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, A.; Lima, C.M.; Barwaldt, E.T.; Bierhals, E.S.; Chagas, B.C.; Salame, J.P.; Silva, A.B.; Nizoli, L.Q.; Nobre, M.O. Platinossomose em felino doméstico no município de Pelotas, RS, Brasil. Vet. Zootec. 2021, 28, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomão, M; Souza-Dantas, L.M.; Mendes-Almeida, F.; Branco, A.S.; Bastos, O.P.M.; Sterman, F.A.; Labarthe, N. Ultrasonography in hepatobiliary evaluation of domestic cats (Felis catus, L., 1758) infected by Platynosomum Looss, 1907. Int. J. App. Res. Vet. Med. 2005, 3, 271–279. [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo, M.R.G.G.; Lima, A.A.; Nicolato, R.L.C. Prevalênciade enteroparasitoses em escolares do bairro Morro de Santana no Municípiode Ouro Preto, MG. Rev. Bras. Anál. Clín. 2005, 37, 191–193. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, M.C.; Morais, J.B.; Machado, J.E.; Poiares-Silva, J. Genotyping of G. duodenalis human isolates from Portugal by PCR-RFLP and sequencing. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2006, 53, 174–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.C.A.; Smith, A. Zoonotic enteric protozoa. Vet. Parasitol. 2011, 182, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, D.E.A.; Benetton, M.L.F.N. Environment factors associate with the occurrence of enteroparasitosis in patients assisted in the public health net in Manaus, state of Amazonas, Brazil. Biosci. J. 2013, 29, 487–498. [Google Scholar]

- Ballweber, L.R.; Xiao, L.; Bowman, D.D.; Kahn, G.; Cama, V.A. Giardiasis in dogs and cats: update on epidemiology and public health significance. Trends Parasitol. 2010, 26, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fantinatti, M.; Gonçalves-Pinto, M.; Lopes-Oliveira, L.A.P.; Cruz, A.M. Epidemiology of Giardia duodenalis assemblages in brazil: There is still a long way to go. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2020, 115, e200431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, L.A; Belizário, T.L.; Pimentel, J.B.; Penatti, M.P.A.; Pedroso, R.S. Prevalence of intestinal parasites in preschool children in the region of Uberlândia, Brazil. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2011, 44, 191–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, M.G. Textbook of Epidemiologia teoria e prática. Guanabara Koogan: Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil, 2012; 616 p. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, A.N.; Menezes, R.C.A.A. Infecção natural de cães por espécies do gênero Cystoisospora (Apicomplexa: Cystoisosporinae) em dois sistemas de criação. Clín. Vet 2003, 42, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Dubey, J.P.; Almeria, S. Cystoisospora belli infections in humans: the past 100 years. Parasitol. 2019, 146, 1490–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funada, M.R.; Pena, H.F.J.; Soares, R.M.; Amaku, M.; Gennari, S.M. Frequency of gastrointestinal parasites in dogs and cats referred to a veterinary school hospital in the city of São Paulo. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 2007, 59, 1338–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbos, K.A.; Freitas, R.J.S; Stertz, S.C.; Carvalho, L.A. Organic vegetables safety: sanitary and nutritional aspects. Ciênc. Tecnol. Alim. 2010, 30, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirley, D.T.; Farr, L.; Watanabe, K.; Moonah, S. A Review of the Global Burden, New Diagnostics, and Current Therapeutics for Amebiasis. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2018, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brener, B; Mattos, D.P.B.G.; Lisboa, L.; Arashiro, E.K.N.; Millar, P.R.; Sudré, A.P.; Duque, V. Frequência de enteroparasitas em amostras fecais de cães e gatos dos municípios do Rio de Janeiro e Niterói. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Vet. 2005, 12, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogrul, O.; Sener, H. The contamination of various fruit and vegetable with Enterobius vermicularis, Ascaris eggs, Entamoeba histolyca cysts and Giardia cysts. Food Control 2005, 16, 559–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, A.A.; Bacalhau, F.; Silva, F.F.; Avillez, C.; Batalheiro, J. Entamoeba histolytica como causa de diarreia crônica. Rev. Bras. Med. Fam. Comunidade 2019, 14, e1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alencar, F.P.; Queiroz, L.N.; Uchôa, S.K.S.; Moura, H.L. Enteroparasitas zoonóticos do gênero Ancylostoma spp. e Toxocara sp. em fezes de cães coletadas em locais públicos do 1° distrito da cidade de Rio Branco-AC. Scientia Naturalis 2020, 2, 241–253. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Chablé, O.M.; García-Herrera, R.A.; Hernández-Hernández, M.; Peralta-Torres, J.A.; Ojeda-Robertos, N.F.; Blitvich, B.J.; Baak-Baak, C.M.; García-Rejón, J.E.; Machain-Williams, C.I. Prevalence of gastrointestinal parasites in domestic dogs in Tabasco, southeastern Mexico. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2015, 24, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira-Sequeira, T.C.G.; Amarante, A.F.T.; Ferrari, T.B.; Nunes, L.C. Prevalence of intestinal parasites in dogs from São Paulo State, Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. 2002, 103, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, I.D.; Thompson, R.C. Enteric parasitic zoonoses of domesticated dogs and cats. Microbes Infect. 2002, 4, 867–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balassiano, B.C.C.; Campos, M.R.; Menezes, R.C.A.A.; Pereira, M.J.S. Factors associated with gastrointestinal parasite infection in dogs in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Prev. Vet. Med. 2009, 91, 324–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilić, T.; Nisavic, U.; Gajic, B.; Nenadovic, K.; Ristic, M.; Stanojevic, D.; Dimitrijevic, S. Prevalence of intestinal parasites in dogs from public shelters in Serbia. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2021, 76, e101653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.I.G.S.; Pena, H.F.J.; Azevedo, S.S.; Labruna, M.B.; Gennari, S.M. Occurrences of gastrointestinal parasites in fecal samples from domestic dogs in São Paulo, SP, Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2016, 25, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Departamento Intersindical de Estatística e Estudos Socioeconômicos. Anuário da saúde do trabalhador; DIEESE: São Paulo, SP, Brazil, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Couto, W.F.; Pereira, R.V.; Figueiredo, B.C.P.; Silva, A.C.; Gramigna, L.L.; Sana, D.E.M.; Gomes, R.S; Andrade, G.F.; Brant, J.F.A.C.; Breguez, G.S.; Silva, M.A.R.; Barbeitos, P.O.; Junior, L.C.P.; Reis, L.E.S.; Jayme, M.F.; Camargo, R.S.; Franco, M.N.; Amaral, M.S.; Nicolato, R.L.C.; Carneiro, C.M.; Reis, A.B. Relação entre parâmetros ambientais, econômicos e socioculturais na identificação de regiões de risco para ocorrência de parasitoses intestinais em uma área rural de ouro preto, MG. Rev. Eletrôn. Farm. 2007, 4, 148–150. [Google Scholar]

- Nunes, M.O.; Rocha, T.J.M. Fatores condicionantes para a ocorrência de parasitoses entéricas de adolescentes. J. Health Biol. Sci. 2019, 7, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramasvaran, S.; Sani, R.A.; Hassan, L.; Kaur, H.; Krishnasamy, M.; Jeffery, J.; Raj. S.; Ghazali, S.M.; Hock, L.C.. Endo-parasite fauna of rodents caught in five wet markets in Kuala Lumpur and its potential zoonotic implications. Trop. Biomed. 2009, 26, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Allen, T.; Murray, K.A.; Zambrana-Torrelio, C.; Morse, S.S.; Rondinini, C.; Di-Marco, M.; Breit, N.; Olival, K.J.; Daszak, P. Global hotspots and correlates of emerging zoonotic diseases. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, V.F.S; Ramos, R.A.N.; Giannelli, A.; Andrade, W.W.A.; Torres-López, I.Y.; Ramos, I.C.N.; Rinaldi, L.; Cringoli, G.; Alves, L.C. Occurrence of zoonotic gastrointestinal parasites of rodents and the risk of human infection in different biomes of Brazil. Braz. J. Vet. Med. 2021, 43, e113820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira-Arbex, A.P.; David, E.B.; Oliveira-Sequeira, T.C.G.; Katagiri, S.; Coradi, S.T.; Guimarães, S. Molecular identification of Ancylostoma species from dogs and an assessment of zoonotic risk in low-income households, São Paulo State, Brazil. J. Helminthol. 2017, 91, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heller, L.; Bastos, R.K.X.; Vieira, M.B.C.M.; Bevilacqua, P.D.; Brito, L.L.A.; Mota, S.M.M.; Oliveira, A.A.; Machado, P.M.; Salvador, D.P.; Cardoso, A.B. Cryptosporidium oocysts and Giardia cysts: environmental circulation and health risks. Epidemiol. Serv. Saúde 2004, 13, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, K.C.P.; Hernández, C.G.; Oliveira, K.R. Frequência de enteroparasitos em amostras de fezes de cães em um município do Pontal do Triângulo Mineiro, Minas Gerais, Brasil. Rev. Patol. Trop. 2014, 43, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, A.M.; Alves, E.G.L.; Rezende, G.F.; Rodrigues, M.C. Ovos de Toxocara sp. e larvas de Ancylostoma sp. em praça pública de Lavras, MG. Rev. Saúde Pública 2005, 39, 293–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macpherson, C.N.L. Human behaviour and the epidemiology of parasitic zoonoses. Int. J. Parasitol. 2005, 35, 1319–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.A.M.; Corrêa, R.S.; Souza, F.S.; Lisboa, R.S.; Pessoa, R.O. Ocorrência de parasitos zoonóticos em fezes de cães em áreas públicas em duas diferentes comunidades na Reserva Desenvolvimento Sustentável do Tupé, Amazonas. Rev. Bras. Hig. Sanid. Anim. 2014, 8, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, D.G.S.; Scheremeta, R.G.A.C.; Oliveira, A.C.S.; Sinkoc, A.L.; Pacheco, R.C. Survey of helminth parasites of cats from the metropolitan area of Cuiabá, Mato Grosso, Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2013, 22, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bricarello, P.A.; Magagnin, E.A.; Oliveira, T.; Silva, A.; Lima, L.M. Contamination by parasites of zoonotic importance in fecal samples from Florianópolis Beaches, Santa Catarina State, Brazil. Braz. J. Vet. Res. Anim. Sci. 2018, 55, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Positives (n) | Prevalence (%) | Confidence Interval (%)* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nematodes | |||

| Ancylostoma spp. | 106 | 29.53 | 25.04-34.44a |

| Toxocara spp. | 27 | 7.52 | 5.22-10.72b |

| Trichuris vulpis | 6 | 1.67 | 0.77-3.60c |

| Cestodes | |||

| Dipylidium caninum | 22 | 6.13 | 4.08-9.10b |

| Protozoa | |||

| Giardia spp. | 12 | 3.34 | 1.92-5.75bc |

| Cystoisospora spp. | 17 | 4.74 | 2.98-7.45bc |

| Entamoeba spp. | 3 | 0.84 | 0.28-2.43c |

| Risk Variable | p-value* | odds ratio** |

|---|---|---|

| Defined race | 0.225 | |

| No defined race | - | |

| With defined race | - | |

| Age | 0.005 | |

| Juvenile/Pup | 0.134 | |

| Adult | 2.167 | |

| Elderly | 0.246 | |

| Host sex | 0.605 | |

| Male | - | |

| Female | - | |

| Average income of owner *** | 0.007 | |

| Until BRL 3,600.00 | 1.815 | |

| Bigger then BRL 3,600.00 | 0.551 | |

| Street access | 0.318 | |

| Yes | - | |

| No | - | |

| Basic home sanitation (sewage collection and piped water) | 0.702 | |

| Yes | - | |

| No | - | |

| Access to sewage, garbage and waste | <0.001 | |

| Yes | 1.171 | |

| No | 0.854 | |

| Updated deworming | <0.001 | |

| Yes | 0.134 | |

| No | 7.444 | |

| Presence of contacting animals (including synanthropic) | 0.019 | |

| Yes | 4.241 | |

| No | 0.236 |

| Species | Positives (n) | Frequency (%) | Confidence Interval (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nematodes | |||

| Ancylostoma spp. | 26 | 47.27 | 33.65-61.20 |

| Toxocara spp. | 2 | 3.64 | 0.44-12.53 |

| Cestodes | |||

| Dipylidium caninum | 4 | 7.27 | 2.02-17.59 |

| Flukes | |||

| Platynosomum fastosum | 3 | 5.45 | 1.14-15.12 |

| Protozoa | |||

| Giardia spp. | 2 | 3.64 | 0.44-12.53 |

| Cystoisospora spp. | 16 | 29.09 | 17.23-42.90 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).