1. Introduction

With the rapid advancement of technology, the need for lightweight and high-strength structural materials in key sectors such as aviation and aerospace, transportation, and high-end equipment manufacturing has become increasingly urgent [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Magnesium (Mg) alloy has emerged as one of the most competitive lightweight metal structural materials [

5,

6,

7,

8]. In particular, the demand for high-performance Mg alloys in major lightweight projects become even more critical, as it holds strategic significance for achieving structural lightweight, energy saving, emission reduction, and safe service [

9,

10,

11]. However, the large critical shear stress difference required for the activation of basal and non-basal slip systems in Mg alloys results in the main slip system being basal slip during plastic deformation [

12,

13,

14]. Conventionally deformed Mg alloys by plastic processing have strong basal texture and anisotropy [

15,

16,

17,

18]. The poor room temperature forming ability and difficult processing and forming of conventionally processed deformed Mg alloys significantly limit the large-scale application and development [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Therefore, improving the room temperature forming performance of Mg alloy sheets remains one of the crucial problems that urgently needs to be addressed.

In recent years, extensive research has been conducted on the poor room temperature forming ability of Mg alloys, with texture control emerging as a current research 7hotspot [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. Currently, texture control technologies primarily focus on two aspects: trace alloying elements addition and plastic deformation processing. The addition of rare earth elements such as Nd, Gd, and Y has been shown to weaken basal texture [

28,

29,

30,

31]. However, precise control of the rare earth element content is necessary as an excessive composition may lead to the formation of second-phase particles that are not conducive to subsequent plastic forming processes. Moreover, rare earth elements are expensive [

32,

33,

34]. Traditional plastic processing methods such as hot extrusion, warm rolling, and cold rolling are commonly used in the processing and preparation of Mg alloy sheet [

35,

36,

37]. These methods result in most crystallites of magnesium alloy sheets being almost parallel to the normal direction of the sheet, exhibiting lower ductility and formability [

38,

39,

40,

41].

Extrusion is a commonly used processing method for preparing Mg alloy sheets [

42,

43,

44]. During plastic deformation, Mg alloys are strongly influenced by external stresses, leading to directional flow and coordinated rotation of the grains relative to the axis of the external force, resulting in the formation of a deformation texture. Changes in external stresses can cause shifts in crystal rotation trends, leading to corresponding changes in the deformation texture. By utilizing specialized extrusion processes, it is possible to control the temperature and stress states during deformation. This can eliminate strong basal plane textures that form due to compressive deformations in the thickness direction of the sheet, and thereby adjust and control the texture of the Mg alloy sheet [

45,

46,

47,

48]. This approach has become an important means of preparing high-performance Mg alloy sheets and improving their subsequent forming abilities.

During the extrusion process, a heated alloy ingot is loaded into the extrusion cylinder of the machine and subjected to strong triaxial compression stress. The resulting Mg alloy sheet has a certain width and thickness after being passed through a specific rectangular die. Conventional extrusion (CE) processes involve symmetrical extrusion forces, leading to a strong basal texture and isotropy of the Mg alloy sheet. However, a new type of asymmetric extrusion for Mg alloy sheets involves constructing asymmetrical internal geometries within the extrusion die to maintain asymmetrical stress and strain during extrusion [

49,

50,

51]. This can increase additional shear strain, refine grain size, overcome the dead zone phenomenon, and improve the smoothness of metal flow and flow property of the metal extrusion process. The flow rate gradient and strain gradient formed during this process cause the c-axis orientation of the sheet grains to tilt along the extrusion direction, weakening the basal texture of the sheet and improving overall mechanical properties [

52,

53,

54].

The author's team has developed various new types of asymmetric geometric structure extrusion dies. This was mainly achieved by introducing different gradient strains from the thickness direction (normal direction) and the transverse direction of the extruded sheets, as well as changing the flow rate, strain, and other parameters of the extruded Mg alloy sheet. Ultimately, this resulted in the regulation of crystal orientation. Different extrusion processes were employed, including asymmetric extrusion (ASE) [

55,

56,

57], differential speed extrusion (DSE) [

58], normal gradient extrusion(NGE) [

59], transverse gradient extrusion(TGE) [

60], asymmetric porthole die extrusion (APE) [

61], asymmetric material composition extrusion [

62], asymmetric curve extrusion(ACE) [

63].

Table 1 summarizes the mechanical properties of Mg alloy sheets processed by different extrusion technologies. It is evident that asymmetric extrusion technology can reduce anisotropy, introduce shear deformation to facilitate grain deviation, promote the activity of basal <a> slip initiation [

64,

65,

66], and improve the plastic deformation ability of magnesium alloy while enhancing processing efficiency for Mg alloy sheet preparation.

2. Processing extrusion technologies of Mg alloy

2.1. Normal direction asymmetric extrusion technology of Mg alloy

Normal direction asymmetric extrusion is a technology used for processing Mg alloy sheets. In this technique, a heat-treated Mg alloy ingot is processed in an extruder equipped with an asymmetric extrusion platform and die. During the extrusion process, the sheet undergoes strong triaxial compressive stress and is then extruded through the die to obtain a Mg alloy sheet with specific width and thickness. Compared to traditional symmetrical extrusion, thick-directional asymmetric extrusion introduces additional shear strain, makes the grain size finer, and improves the smoothness of metal flow, thereby enhancing the flowability of the metal extrusion process. By adjusting the contact distance and angle between the working belt of the die and the upper and lower surfaces of the sheet, a non-symmetric shear strain gradient along the thickness direction of the sheet (parallel to the thickness plane of the sheet) can be formed. Shear deformation along the direction parallel to the sheet's thickness will induce grain orientation with localized strain, which can significantly improve the basal texture of Mg alloy thin sheets [

49,

68]. Thus, the c-axis orientation of the sheet grains tilts along the direction of extrusion, weaken the basal texture of the sheet, and thus improve the overall mechanical performance of the extruded sheet.

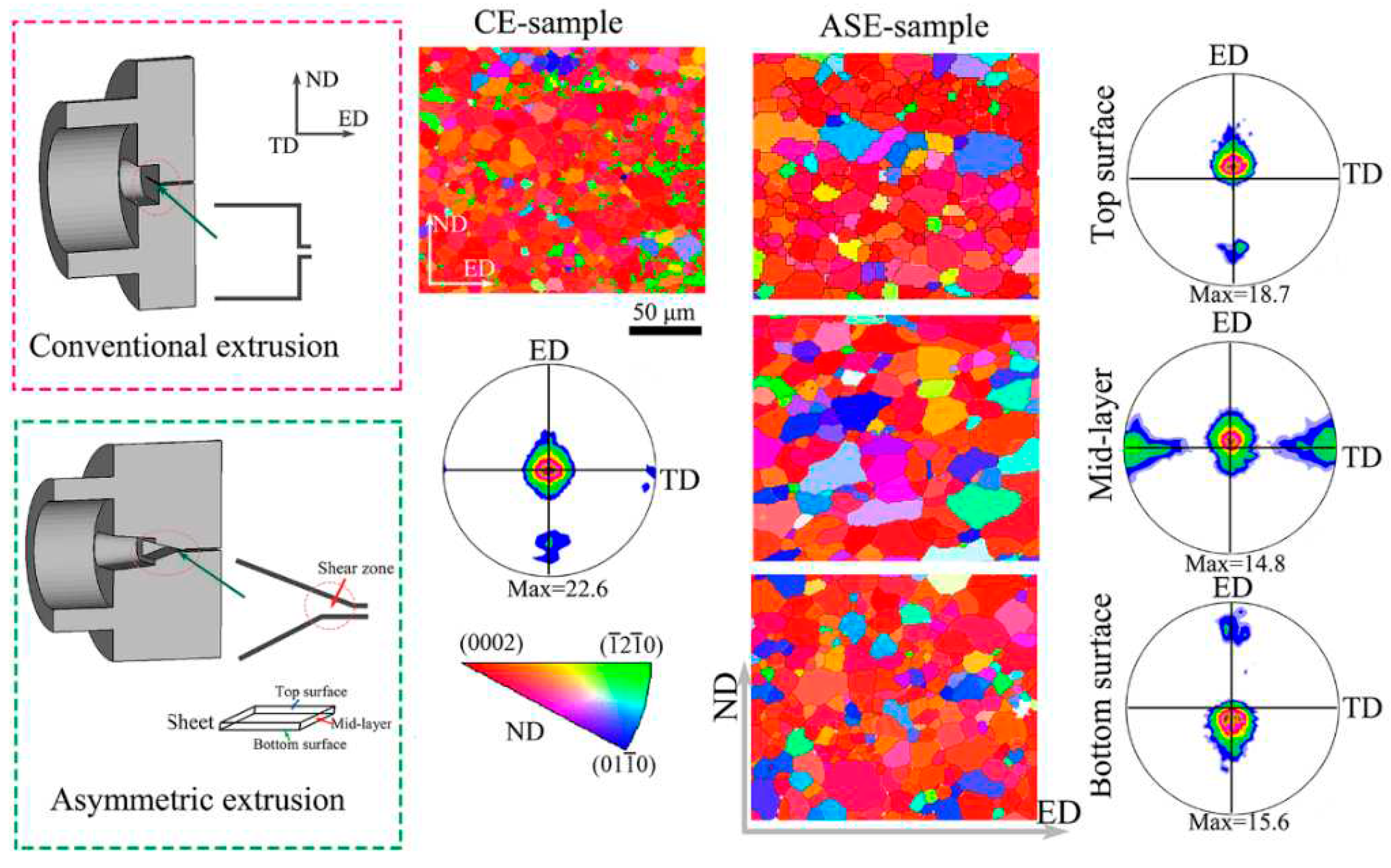

2.1.1. Asymmetric extrusion (ASE)

Figure 1 shows the (0002) pole figures and corresponding EBSD analysis of CE and ASE extruded sheets. The CE sheet exhibits a strong (0002) basal plane texture with relatively uniform organization, while the ASE sheet displays a weakened basal plane texture but uneven organization in the thickness direction. As presented in

Figure 2(b), numerous small dynamic recrystallization (DRX) grains can be observed around the elongated grains, and the ED deviation of the basal plane texture axis is approximately 12°. Coarse grains are elongated and then deviate from the basal orientation.

The CE sheet is subjected to a strain that compresses the sheet thickness and elongates it along the extrusion direction. In contrast, the Mg alloy sheet during ASE processing also experiences shear stress due to the different velocities of the upper and lower parts, resulting in shearing deformation in the sheet thickness direction, with the slow side moving rearward and the fast side moving forward. Due to the large degree of extrusion deformation and high extrusion ratio of about 100:1, the Mg alloy sheet has a high stored energy, and the driving force for recrystallization is strong, leading to a high nucleation and growth rate. However, when the deformation amount is significant, the nucleation rate's increase rate is greater than that of the growth rate. This is because the generated dislocations cannot be eliminated in time and thus increase, leading to an increase in recrystallization nucleation. Following recrystallization, the grain size is refined. Therefore, increasing the strain amount of AZ31 Mg alloy facilitates dynamic recrystallization, resulting in finer grains.

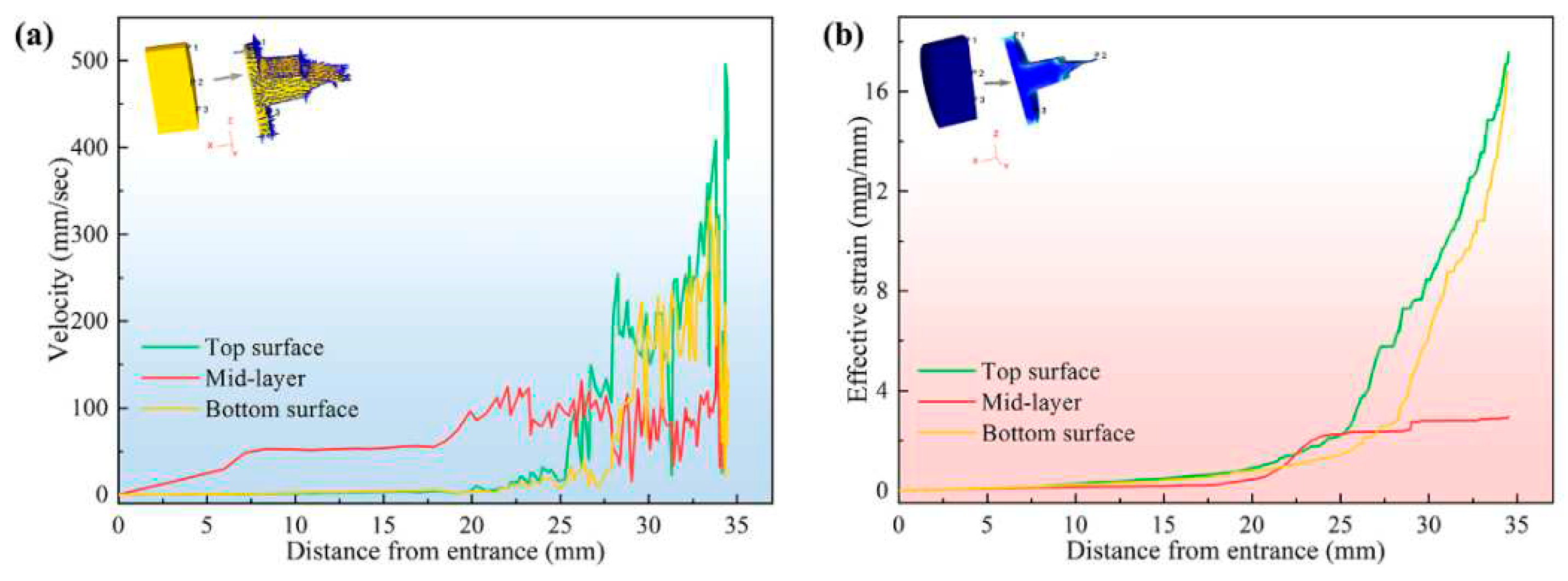

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of the velocity and effective strain of Mg alloy sheet processed by ASE. The flow velocity and strain distribution along the thickness direction of AZ31 Mg alloy sheets during the ASE process using the ASE die (L=4 mm) were analyzed [

69]. It can be seen that there is a gradient in both strain and flow velocity along the thickness direction of the sheet. It can be shown that as the Mg alloy enters the shearing deformation zone of the asymmetric extrusion, both strain and flow velocity gradually increase during the extrusion process, with the upper part of the shearing zone being the maximum value. From the simulated results of billet flow velocity in

Figure 2(b), it can be learned that effective strain of the upper, middle, and lower parts of the ASE extruded sheets are 4.7, 3.7, and 1.4, respectively, and decrease gradually along the thickness direction of the sheet. The results of Finite Element Method (FEM) simulation reveal that larger strains occur on the upper surface, and smaller dynamic recrystallization grains appear. Moreover, the c-axis orientation of the grains deviates along ED due to shear deformation.

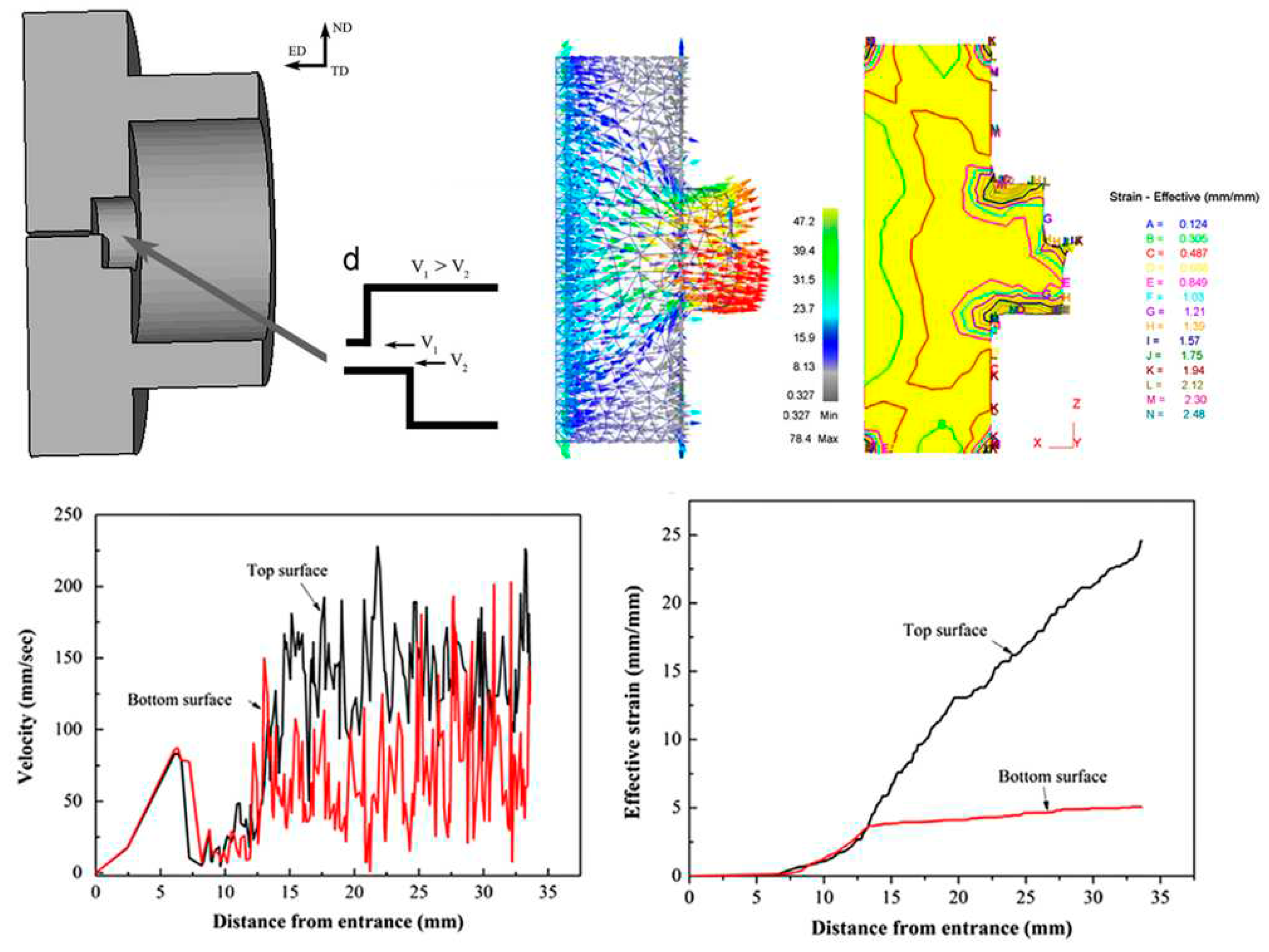

2.1.2. Differential speed extrusion (DSE)

Previous studies have shown that Mg alloy flows smoothly during asymmetric extrusion, and the stress and strain experienced by the metal during the extrusion process are relatively small [

55,

69]. In order to investigate the microstructure and properties of the AZ31 alloy extruded sheet under greater stress and strain conditions, we designed a differential speed extrusion (DSE).

Figure 3 presents the schematic sectional view and FEM results of the DSE process. The DSE die is capable of creating a significant difference in flow rate between the upper and lower surfaces of the metal billet, as well as a sharp change in flow rate, resulting in a larger strain gradient along the thickness direction of the extruded sheets. This can refine the grain size and improve its strength and plasticity. Finite element simulation was conducted to study the velocity and strain distribution along the thickness direction during the DSE process. The results indicate that there is a certain gradient in strain and velocity along the thickness direction of the sheet. The velocity ratio between the upper and lower parts was 2:1, meaning that the strain was higher and the velocity was faster on the upper surface. During the extrusion deformation process, the uneven distribution of strain would cause different degrees of dynamic recrystallization in the Mg alloy. The areas with higher strain would undergo greater dynamic recrystallization, resulting in smaller equiaxed grains.

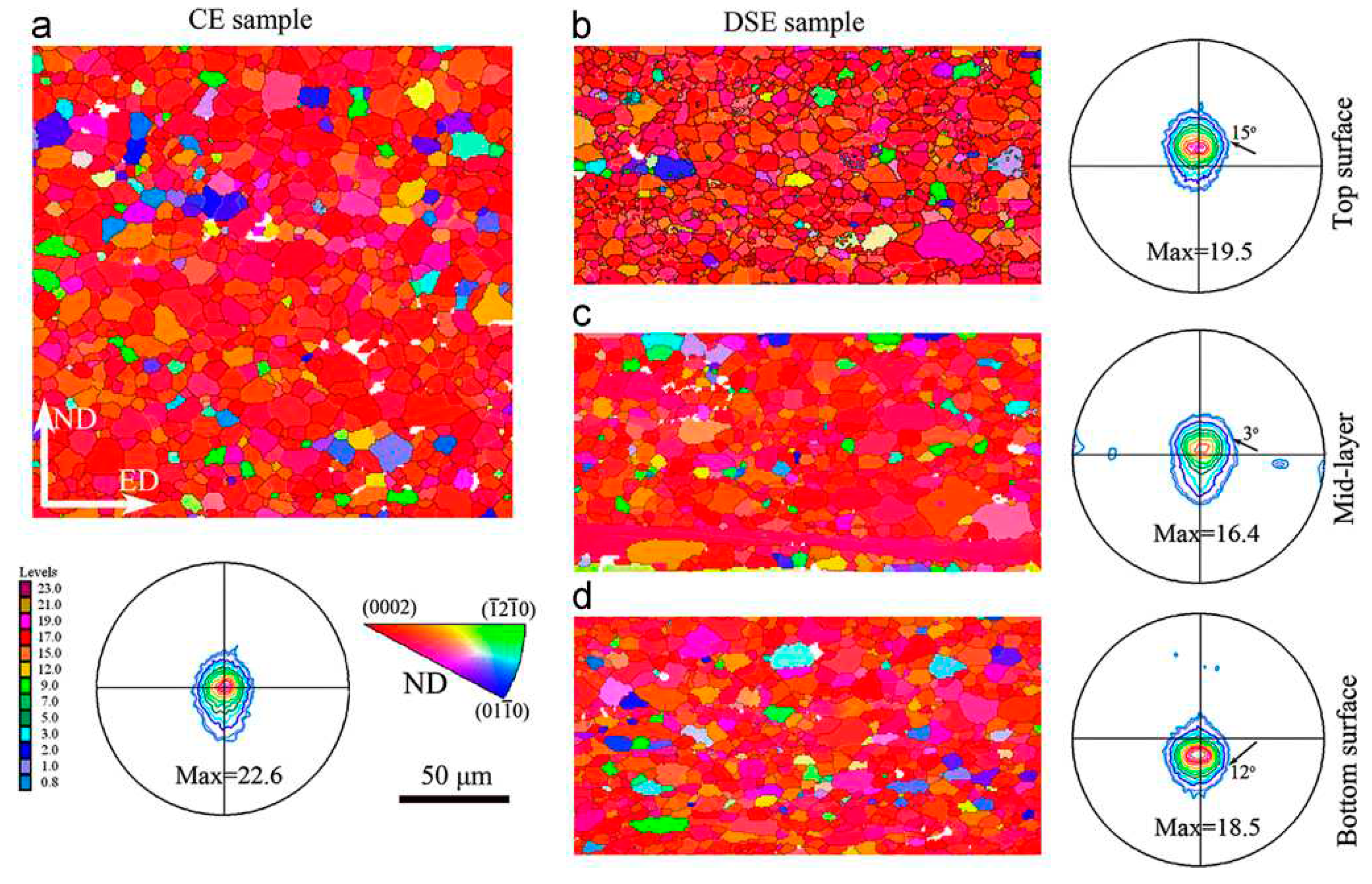

Figure 4 shows the (0002) pole figure and EBSD grain orientation of the CE and DSE sheets. It is evident that the microstructure of the DSE sample is non-uniform along the thickness direction. As shown in

Figure 4(b), the coarse grains are elongated and deviated from the c-axis of the basal plane, and there are many small dynamic recrystallized (DRX) grains around the elongated grains. Moreover, the basal texture is tilted by about 15

o towards ED. The relationship between the average grain size and the Zener-Hollomon (Z) parameter is expressed as

where the temperature-corrected strain rate Z is Z = ε·exp(Q/RT). According to this equation, the larger strain on the upper surface results in smaller grain size[

70,

71], with a value of about 8 μm, while the grain size on the lower surface is about 9 μm. Meanwhile, the basal texture on the lower surface is tilted by about 12

o towards ED, and the DRX grains on both upper and lower surfaces are tilted in the direction of the applied shear force. Thus, the majority of grains tend to undergo prismatic<a> slip rather than basal<a> slip due to the shear action. This prismatic<a> slip causes the grains to rotate and changes their orientation, while increasing the strain between adjacent grains, leading to the generation of secondary stresses between grains, which in turn alters the strain state of each grain. As the Mg alloy undergoes extrusion deformation, when the slip distance of the initial slip system reaches a certain degree, the grain orientation and stress state change significantly, so that the orientation factor of the other slip systems is higher than that of the current system [

72,

73], thereby altering the activation status of the slip system and ultimately achieving continuous strain.

2.1.3. Normal gradient extrusion (NGE)

To further understand the difference in rheological behavior of AZ31 Mg alloy between CE and NGE processes, the stress state of AZ31 Mg alloy during extrusion process was analyzed as shown in

Figure 5. Our research team has previously investigated the microstructure and mechanical properties of Mg alloys prepared by NGE and CE processes [

59]. The included angles of the upper and lower dies of the NGE extrusion die are processed at 30°, 45°, 60°, and 90°, In CE symmetrical extrusion, the upper and lower surfaces of the AZ31 magnesium alloy sheet in the forming area are subjected to the same force from the die (PT = PB). However, in NGE non-symmetric extrusion process, the stress on the AZ31Mg alloy is more complex. When the AZ31 Mg alloy flows into the deformation zone (red zone), it is subjected to a force P applied by the die, which can be divided into two components (P

ED and P

ND, respectively). This indicates that the AZ31 Mg alloy bears additional normal stress P

ND in the NGE extrusion die. This is subjected to different stress on the upper and lower surfaces of the extruded sheet (P

T ≠ P

B), resulting in the formation of different flow velocity (V

T ≠ V

B) on the upper and lower surfaces of the extruded sheet. This is conducive to the formation of additional shear strain along the ED direction during sheet forming [

74,

75]. Therefore, a large effective strain gradient is formed along the thickness direction of the extruded sheet in NGE extrusion process. Large effective strain and strain gradient can effectively refine the microstructure of AZ31 Mg alloy sheet and weaken the texture.

Figure 6 illustrates EBSD analysis and (0002) pole figures of the upper surface, middle layer, and lower surface of AZ31Mg alloy sheet extruded by NGE-45o process. The texture strength varies in different regions of the same extruded sheet. Specifically, the middle layer of the extruded AZ31 sheet shows a bimodal texture feature, elongated along the ED direction. The texture strength of the middle layer in NGE-45 o sheet is 8.0, reaching the lowest value. Additionally, the basal texture on the upper surface of GASE-45 o sheet is more dispersed and inclined along the ED direction, and new texture components appear along the ED direction. GASE-45 o sheet exhibits lower texture strength in the corresponding region.

2.2. Normal direction asymmetric divergent die extrusion technologies of Mg alloy

The flat die preparation process is relatively straightforward, but the cross-sections of the die cavity and the corresponding extrusion cylinder are typically circular, which does not match the rectangular cross-section of the extruded sheet. As a consequence, uneven deformation occurs along the width direction of the sheet, particularly for sheets with a large aspect ratio. To address this issue and improve the efficiency and quality of extruded sheets, practical production and industrial applications often incorporate flat extrusion cylinders and diverter dies for extruding wide sheets with a large aspect ratio [

53,

76].

2.2.1. Asymmetric porthole die extrusion (APE)

Figure 7 presents schematic diagrams of the symmetric flow-diverting die and three types of asymmetric flow-diverting dies. Different from conventional dies, the flow-diverting die features an enlarged entry and a flow-diverting baffle at its entrance, allowing for smooth division of the billet into two metal flows during the extrusion process and exposing a new interface. Subsequently, in the high-temperature and high-pressure environment of the die cavity, the newly exposed interfaces can bond tightly to form a good metallurgical bonding interface. Based on the symmetric flow-diverting die, we modified the structure of the flow-diverting baffle to create specific asymmetric flow-diverting dies with different angles (45°, 60°, and 90°). As seen from the geometric shapes of the AZ31 alloy billets, the billet completely fills the die cavity during the extrusion process. The streamline distribution of the alloy shows good symmetry along the ED direction, but there is a difference in streamline angle between the extrusion streamline and the ED direction. Specifically, the streamline angle for symmetrical extrusion is 5°, whereas for the three types of APE asymmetric dies, the streamline angles are 12°, 17°, and 21°, respectively. This indicates that the use of asymmetric flow-diverting dies significantly increases the streamline angle, which gradually increases with the increasing bridge angle of the die. Consequently, the geometric asymmetry of the asymmetric flow-diverting die results in significant asymmetrical flow of the alloy billets [

77,

78]. Overall, these findings have implications for the design and optimization of flow-diverting dies in the extrusion process.

Figure 8 shows the microstructures and texture evolutions of AZ31Mg alloy during the CE and APE processes. The CE extruded sheet exhibits typical basal texture characteristics, with the maximum pole density located at the center of (0002) pole figure and a relatively high maximum pole density value. In contrast, for the three types of asymmetric flow splitting pattern extruded sheets, there are differences not only in the distribution of maximum pole density, but also in significant differences in the numerical values of maximum pole density. In terms of the distribution of maximum pole density, all three extruded sheets exhibit a certain degree of angle deviation along the ED direction, with the angle gradually increasing as the flow splitting angle increases, from about 15.3° to about 21.3°. The change in the deviation angle of the maximum pole density along the ED direction is consistent with the change in the asymmetric flow splitting angle. This indicates that introducing an asymmetric flow splitting angle leads to a deviation of the maximum pole density of the extruded sheet along the ED direction. The decrease in the maximum pole density and the more dispersed pole axis indicates that the asymmetric flow splitting pattern extrusion can more effectively weaken the basal texture of magnesium alloy compared to the CE and PE symmetric extrusion, especially for the APE-90 flow splitting pattern extrusion with large flow splitting angle. To further elucidate the mechanism of the weakening of the texture of APE-90 sheet, the microstructure and texture evolution during CE and APE-90 asymmetric extrusion are analyzed. In the CE extrusion process, every position from 1 to 4 shows uneven microstructure, which is a typical mixed crystal structure. In the APE-90 extrusion process, it gradually transforms from dynamic recrystallization structure and uneven mixing of undeformed grains in the initial stage of extrusion to a relatively uniform and complete dynamic recrystallization structure, especially at positions 3 and 4 where grain size is smaller, indicating strong shear strain in the final stage of extrusion that promotes dynamic recrystallization. As the extrusion process progresses, the basal slip of the alloy gradually dominates, resulting in the maximum pole density moving from the edge to the center of the pole figure. Compared with the CE extrusion process, the APE-90 extrusion process delays the formation of basal texture and the turning of the pole axis to the central position. APE-90 extruded sheets retain more non-basal orientation grains, forming a weaker basal texture inclined along the extrusion direction, and more dispersed [

79,

80]. This difference is closely related to the different extrusion channels of the CE symmetric extrusion die and the APE-90 asymmetric extrusion die, which in turn lead to different flow characteristics and shear stresses.

2.2.2. Asymmetric billet split flow die extrusion

Developing bimetallic or multicomponent laminated composite materials can integrate the advantages of two or more base metal materials. AZ31/Al 6061 [

81], AZ31/WE43 [

82], and AZ31/AZ91 [

83] are various bimetallic composite materials that can be prepared by solid-liquid composite. However, high processing temperatures deteriorate their service performance. Multi-layer bimetallic or multicomponent composite materials can be prepared, such as Al/AZ31 [

90] and Mg-12Li-1Al/Mg-5Li-1Al (LA121/LA51, wt.%) [

86], can be prepared using solid-solid composite methods such as direct co-extrusion [

84,

85], accumulative roll bonding [

86,

87], accumulative extrusion-bonding [

88], and equal channel angular pressing [

89]. Furthermore, appropriate annealing processes can enhance the interfacial binding ability by promoting atomic diffusion between the base metal layers. Our team selected AZ31 and low rare earth content Mg-0.3wt.%Y (W0) alloy and used the difference in material types to achieve asymmetric deformation extrusion by building on the previous symmetric flow splitting die.

Figure 9 shows the schematic of the asymmetric billet split (AZ31/W0) flow die extrusion fabrication process. This led to the extrusion preparation of bimetallic laminated composite materials.

Figure 10 shows the microstructure and (0002) pole figure of longitudinal section of AZ31 sheet, W0 sheet, and AZ31/W0 laminated composite sheet. It can be seen that there are significant differences in the microstructure and texture of AZ31/W0 laminated composite sheet compared to single AZ31 sheet and W0 sheet. The average grain size of AZ31 layer and W0 layer in AZ31/W0 laminated composite sheet are about 18.4 and 9.6 μm, respectively. The average grain size of the composite sheet prepared by symmetric flow splitting die extrusion is larger than that of the ordinary extruded sheet. As shown in

Figure 8(e-h), it can be seen that compared with the AZ31 sheet with strong basal texture (23.34), the strength of basal texture of AZ31 layer in AZ31/W0 composite sheet is lower (15.51), and the distribution is more scattered. The maximum pole density and distribution of W0 layer in AZ31/W0 composite sheet are similar to those of W0 sheet, with a maximum pole density offset of about ±30° along the ED and a weak orientation distribution along TD, forming a typical rare earth bimodal texture feature. It can be seen that there is a small interdiffusion zone between the AZ31 layer and the W0 layer, and the width of the interdiffusion zone is about 0.35 μm. According to the selected area electron diffraction (SAED) observation of dark and bright regions, the phases in both regions are magnesium matrix phase, and no compound phase was observed. The high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) image shows a crystallographic interface between the Mg layer and the diffusion zone. The interplanar spacings of {10-10} crystal planes in the matrix and diffusion zone are both 0.160 nm, which can be confirmed as Mg supersaturated solid solution [

91,

92,

93]. The crystal plane angle between the {10-10} crystal plane of the Mg layer and the {10-10} crystal plane of the diffusion zone is about 17° measured by the crystal plane angle measurement. A small interdiffusion zone is formed between the AZ31 layer and the W0 layer in the AZ31/W0 laminated composite sheet, and there is a good crystallographic matching relationship between the matrix and the diffusion zone. This diffusion zone enables good bonding between the AZ31 layer and the W0 layer.

2.3. Transverse direction asymmetric extrusion technology for Mg alloy

Our research team proposed an asymmetric extrusion process along the transverse direction of the sheet. By designing the transverse geometry structure of the extrusion die, we constructed a gradient strain in the transverse direction of the extruded magnesium alloy sheet. Based on optimizing the process parameters, both the basal texture and microstructure of the magnesium alloy extruded sheet were regulated to improve its plastic formability [

24,

25]. The ultimate goal is to enhance the plasticity of the extruded magnesium alloy sheet through this process.

2.3.1. Asymmetric extrusion (ASE)

We have designed a transverse gradient asymmetric extrusion flat die, as illustrated in Figure 11, which features an isosceles triangle space at the exit of the die cavity. By using the two sides of the triangle, we are able to regulate the flow velocity difference between the center and edges of the sheet along the transverse direction, resulting in a shear effect and forming asymmetric stress and strain. We conducted various degrees of asymmetric extrusion experiments by adjusting the inclination angle θ (θ=0°, 15°, 30°, 37°, 45°, 52°, and 60°) of the extrusion die. The die becomes a conventional extrusion (CE) die when θ=0°, while it becomes a transverse gradient extrusion (TGE) die with different degrees of asymmetry when the inclination angle θ is set to 15°, 30°, 37°, 45°, 52°, and 60°.

Figure 11 shows the velocity distribution on the ED-TD plane at the exit of the extrusion die during TGE-52 asymmetric extrusion processes. In the CE process, the velocity direction is mainly aligned with the ED direction. In contrast, in the TGE-52 asymmetric extrusion process, the flow velocity deviates towards TD along ED at the exit of the die, except for the center area of the extruded sheet. This introduces a new flow velocity V

TD along TD, which is beneficial in deflecting the basal texture during the extrusion process. Moreover, the angle of deflection from ED to TD increases as V

TD increases (V

TD=V

ED*tanθ), and as the inclination angle θ of the die rises.

Figure 12 shows the evolution of microstructure and texture near extrusion die exit before and after sheets forming in TGE Process. During the initial stage of extrusion, the Mg alloy experiences relatively small deformation of its coarse grains, which leads to favorable conditions for the initiation of tensile twinning and results in the formation of many twinned grains [

94,

95]. At position A, the microstructure is non-uniform, while many small recrystallized grains appear at position B. Additionally, many small green-colored grains with their c-axis inclined along the TD direction can be observed at various locations in the central region of the TGE-52 extruded sheet. The microstructure and texture evolution at the 1/4 edge of the TGE-52 extruded sheet differ significantly from those observed in the central region. The microstructure of the central region of the TGE-52 extruded sheet at the exit of the extrusion die comprises small recrystallized grains. As we move from position F (near the sheet forming area) to position I (far from the sheet forming area), the grains become further refined, and a more uniform microstructure is achieved at position I. The texture features of the extruded AZ31Mg alloy sheet exhibit significant variations in different areas. At position F, a basal texture feature with a maximum density of 11.6 is observed. At position G, the basal poles deviate from the ED direction, while at position H, the basal texture component is further reduced. By position I, the basal texture component disappears entirely, and the basal poles deviate greatly from the ED direction, ultimately forming a double peak texture.

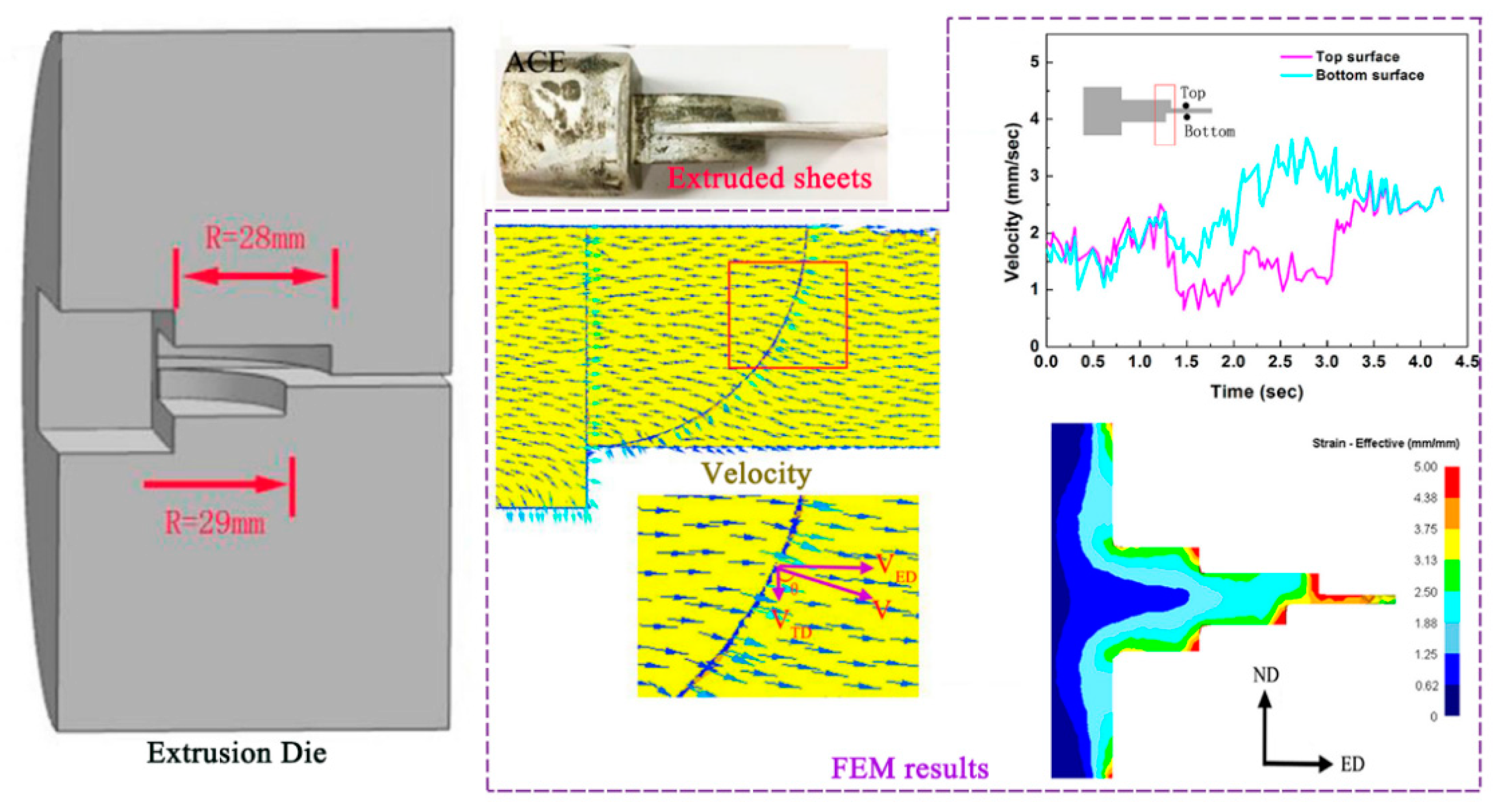

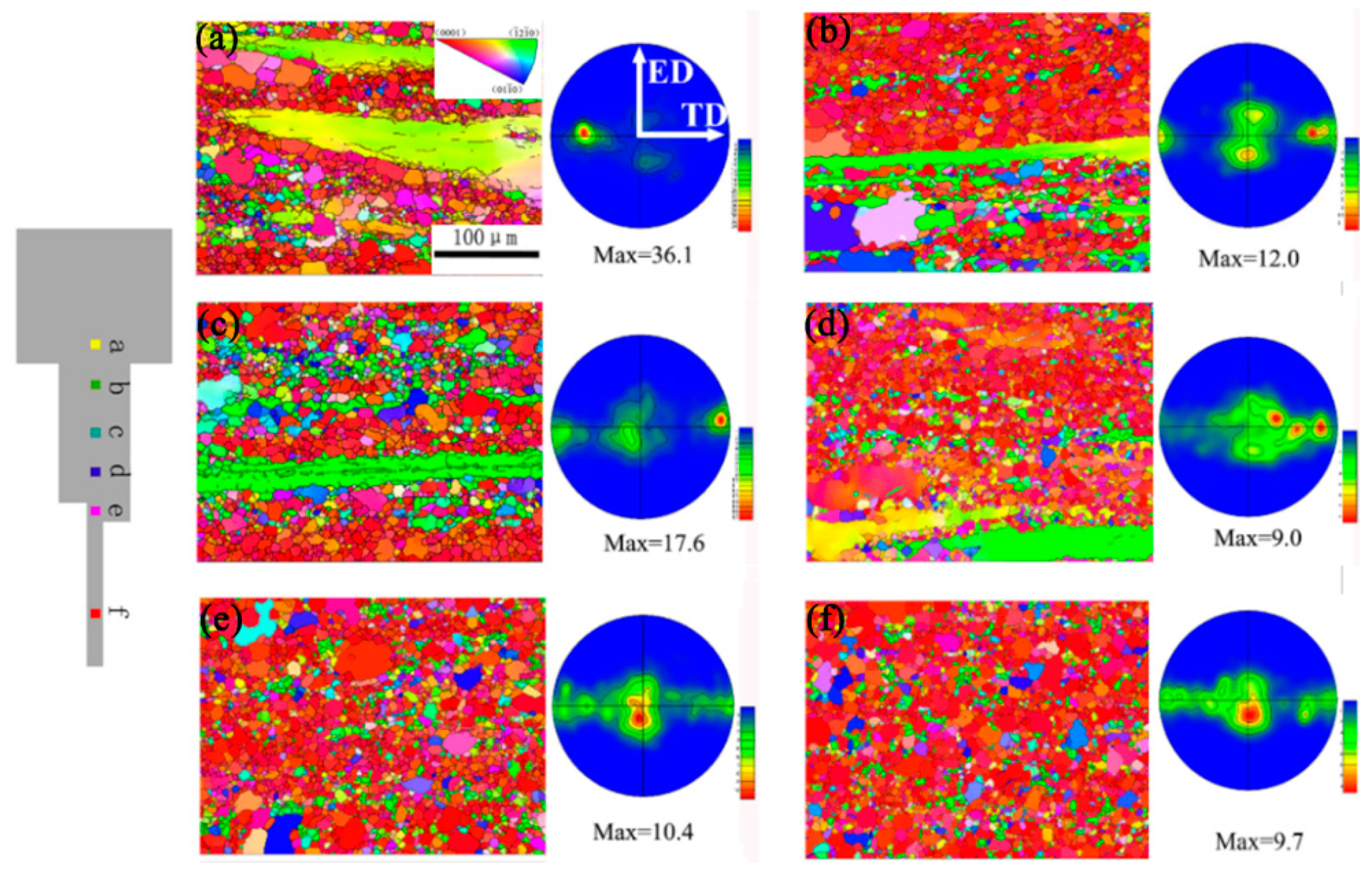

2.3.2. Asymmetric curve extrusion (ACE)

This work combines the design of thick and transverse asymmetric structures and designs and manufactures three-dimensional asymmetric curved extrusion dies, as shown in

Figure 13. The upper and lower surfaces at the sheet forming location are designed as circular arcs with different radii of 28 and 29mm respectively, exhibiting parallel rheological channels of different lengths. The extrusion velocity direction is deflected from ED to TD at the sheet forming location due to the change of the extrusion die. The AZ31 Mg alloy generates separate velocities along the ED (VED) and TD (VTD) directions during the extrusion process, and the ACE process can effectively introduce additional velocities in the TD direction (VTD). The changes in velocity on the upper and lower surfaces of sheet are almost identical in the CE process owing to the symmetrical structure of the die. The rheological behavior of AZ31 alloy relative to the middle layer of the extruded sheet shows an asymmetric distribution in ACE process. The velocity on the upper surface of the extruded sheet is lower than that on the lower surface, and the formation of velocity differences is beneficial for introducing asymmetric shear stress during the extrusion process [

42,

44].

Figure 14 shows the microstructure and texture evolutions of the ACE sheets. ACE alloy billet samples display many small dynamic recrystallized grains appear in blue and green colors, and the c-axis of these grains is deflected from ND to TD. This asymmetric extrusion process introduces new texture components along TD. Compared with CE symmetrical extrusion alloy billet samples, the ACE samples show weaker texture strength at the same distance from the sheet forming location. At the same time, the extruded AZ31 alloy sheet obtains a finer microstructure and weaker basal texture. In addition, the basal pole strength of dynamic recrystallized grains in ACE extruded alloy billet samples (

Figure 14 a, c, d, and e) is always lower than that in CE alloy billet samples at the same distance from the sheet forming location. This is because the ACE extrusion die has a significant difference in billet flow velocity in the thickness and transverse directions of the sheet, resulting in larger additional shear stress and promoting the dynamic recrystallization process of non-basal oriented grains, which is manifested as weaker basal texture at the macro level.

3. Conclusions and outlooks

Conducting research on the strengthening mechanism and formability of Mg alloy sheets holds significant potential for providing superior materials with desirable characteristics, such as lightweight, shock absorption, noise reduction, and electromagnetic shielding. In recent years, extensive advancements have been made in high plastic deformation Mg alloys and plastic processing technology. Based on asymmetric extrusion technology, a novel approach introduces non-symmetric strain in the thickness and transverse directions of the extruded sheet to regulate the temperature and stress state during deformation. This process eliminates the strong basal texture formed by compression deformation in the thickness or transverse direction of the sheet and adjusts and controls the texture of Mg alloy sheets, thereby enhancing the subsequent forming properties of the sheets. We have developed multiple types of concentrated asymmetric extrusion processing technologies, including asymmetric extrusion (ASE), differential speed extrusion (DSE), normal gradient extrusion (NGE), transverse gradient extrusion (TGE), asymmetric porthole die extrusion (APE), asymmetric material composition extrusion, and asymmetric curve extrusion (ACE). These innovative extrusion techniques provide a crucial pathway to prepare high-performance Mg alloy sheets, offering a promising strategy for improving the material properties of Mg alloys.

By adjusting the distance and angle between the working band of the mold and the upper and lower surfaces of the sheet, we have constructed a non-symmetric shear strain gradient along the thickness direction of the sheet (parallel to the sheet thickness surface), causing the c-axis of the Mg alloy to deviate during dynamic recrystallization. Short-process hot extrusion and shear strain effectively weaken the basal texture, significantly improving the mechanical properties of Mg alloy thin sheets. Recent years have witnessed significant progress in the preparation and processing of high-performance Mg alloy sheets.

- (1)

Mg-Al-Ca-Mn series microalloyed Mg alloys have been developed, whereby adding rare earth elements like Ce, Y, and Gd, even at low concentrations, strongly weakens the basal textures.

- (2)

Plastic processing technologies such as equal channel angular rolling (ECAR) and pre-deformation control have been developed, introducing gradient strain into the sheet plane, which is conducive to a large amount of basal slip and tensile twinning opening. As a result, forming a c-axis//RD texture orientation feature with a certain {10-12} twin structure leads to significantly enhancing the room temperature formability of Mg alloy sheets.

- (3)

Wide-width Mg sheet near-isothermal rolling technology has been developed, realizing high-precision rolling of large coil weight wide-width Mg alloy sheets rolls, significantly improving the rolling formability, organization, and performance uniformity of Mg alloy sheets.

In order to achieve efficient preparation of high-formability Mg alloy sheets with weak basal texture and low isotropy, future work should focus on the following aspects.

- (1)

The development of low-cost, low-content Mg-Al series Mg alloys and their sheet processing and preparation technology is crucial. This can be achieved by regulating crystal orientation through alloy elements to improve the balance between Mg alloy strength and formability.

- (2)

Optimizing the plastic deformation strain path and prefabricating the twinning orientation of Mg alloy sheets is necessary. Coupling with Mg alloy recrystallization behavior can form crystal orientations favorable for Mg alloy plastic deformation, ultimately controlling the isotropy and formability of Mg alloy sheets.

- (3)

Exploring the activity of non-basal < a > dislocations and < c + a > dislocations through plastic deformation strain, further systematically theorizing and experimentally verifying, quantitatively analyzing the relationship between dislocation activity and plastic deformation mechanism, and predicting the formability of Mg alloys.

- (4)

Developing high-strength and tough deformation Mg alloy extrusion die design and complete sets of processing technology is essential. Efficient production and processing technology of wide-width Mg alloy profiles, as well as high-precision profile heat treatment, straightening, and other finishing technologies and equipment, should be developed. In addition, ultra-wide and high-precision deformation Mg alloy profiles should also be investigated.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, Q.S.Yang, B.Jiang and F.S.Pan; methodology, D.Zhang; investigation, P.Peng and G.B.Wei; writing—original draft preparation, Q.S.Yang.; writing—review and editing, J.Y.Zhang and B.Jiang; supervision, F.S.Pan. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (52271091, 52271092), Chongqing Science and Technology Commission (CSTB2022 NSCQ-MSX0891).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no conflict of interest with any person or foundation.

References

- Zemkova, M.; Minarik, P.; Dittrich, J.; Bohlen, J.; Kral, R. Individual effect of Y and Nd on the microstructure formation of Mg-Y-Nd alloys processed by severe plastic deformation and their effect on the subsequent mechanical and corrosion properties. J. Magn. Alloy. 2023, 11, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Pan, J.; Xie, W.; Yang, J.; Zhang, W.; Chen, W. Effects of Extrusion Ratio on the Microstructure, Texture and Mechanical Properties of Mg-2. 5Nd-0.5Zn-0.5Zr Alloy Sheets. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2023, 32, 4834–4845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Chen, J.; Xiong, X.; Peng, X.; Chen, D.; Pan, F. Research advances of magnesium and magnesium alloys worldwide in 2021. J. Magn. Alloy. 2022, 10, 863–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Jiang, B.; Song, B.; Yu, Z.; He, D.; Chai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Pan, F. The effects of orientation control via tension-compression on microstructural evolution and mechanical behavior of AZ31 Mg alloy sheet. J. Magn. Alloy. 2022, 10, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, M.Z.; Sasaki, T.T.; Suh, B.C.; Nakata, T.; Kamado, S.; Hono, K. A heat-treatable Mg–Al–Ca–Mn–Zn sheet alloy with good room temperature formability. Scr. Mater. 2017, 138, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Amirkhiz, B.S.; Lloyd, D.J. Improvement of Superplasticity in High-Mg Aluminum Alloys by Sacrifice of Some Room Temperature Formability. Metall. Mater. Trans A. 2018, 49, 1962–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Li, C.; Xin, Y.; Chapuis, A.; Huang, X.; Liu, Q. The mechanism for the high dependence of the Hall-Petch slope for twinning/slip on texture in Mg alloys. Acta Mater. 2017, 128, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Jiang, B.; Song, B.; Zhang, J.; Pan, F. Improving Strength and Formability of Rolled AZ31 Sheet by Two-Step Twinning Deformation. Jom 2020, 30, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Ahmad, R.; Yin, B.; Sandlöbes, S.; Curtin, W.A. Mechanistic origin and prediction of enhanced ductility in magnesium alloys. Science 2018, 359, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S.; Dogan, E.; Kondori, B.; Karaman, I.; Benzerga, A.A. Towards designing anisotropy for ductility enhancement: A theory-driven investigation in Mg-alloys. Acta Mater. 2017, 131, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.B.; Davies, C.H.J.; Brokmeier, H.G.; Bolmaro, R.E.; Kainer, K.U.; Homeyer, J. Deformation and texture evolution in AZ31 magnesium alloy during uniaxial loading. Acta Mater. 2006, 54, 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, C.; He, B.; Zheng, T.; Tang, A.; Pan, F. Influence of extrusion conditions on microstructure and mechanical properties of Mg-2Gd-0. 3Zr magnesium alloy. J. Magn. Alloy. 2022, 10, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Peng, P.; Luo, A.A.; She, J.; Tang, A.; Pan, F. Dynamic precipitation and enhanced mechanical properties of ZK60 magnesium alloy achieved by low temperature extrusion. Materials Science and Engineering a-Structural Materials Properties Microstructure and Processing 2022, 829. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, D.; Xu, T.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, J. Achieving high-strength in Mg-0.8Zn-0.2Zr (wt.%) alloy extruded at low temperature. Materials Science and Engineering a-Structural Materials Properties Microstructure and Processing 2021, 822. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Jiang, B.; Dai, J.; Li, R.; Pan, F. Mechanical properties and anisotropy of AZ31 alloy sheet processed by flat extrusion container. J. Mater. Res. 2013, 28, 1148–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.S.; Jiang, B.; Zhou, G.Y.; He, J.J.; Pan, F.S. Enhancing strength and ductility of AZ31 magnesium alloy sheets by the trapezoid extrusion. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2013, 30, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Guo, N.; Liu, T.; Yang, Q. Improvement of formability and mechanical properties of magnesium alloys via pre-twinning: A review. Materials & Design (1980-2015) 2014, 62, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Jiang, B.; Song, B.; Yu, D.; Chai, S.; Zhang, J.; Pan, F. Mechanical behavior and microstructure evolution for extruded AZ31 sheet under side direction strain. Progress in Natural Science-Materials International 2020, 30, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Wu, G.; Liu, W.; Sun, J.; Ding, W. Role of extrusion temperature on the microstructure evolution and tensile properties of an ultralight Mg-Li-Zn-Er alloy. J. Alloys. Compd. 2021, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.G.; Li, H.R.; Pan, H.C.; Xie, D.S.; Zhang, J.H.; Fang, D.Q.; Dai, Y.Q.; Zhao, D.Y.; Zhang, H. Achieving exceptionally high strength in binary Mg-13Gd alloy by strong texture and substantial precipitates. Scr. Mater. 2021, 193, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Nie, K.; Deng, K.; Yang, A. Microstructures and Mechanical Properties of Low-Alloyed Mg-Zn-Y Magnesium Alloy. Rare. Metall. Mat. Eng. 2021, 50, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, W.; Yang, J.; Pan, J.; Wang, H.; Chen, W.; Cui, G. Evolution of Microstructures, Texture, Damping and Mechanical Properties of Hot Extruded Mg-Nd-Zn-Zr Alloy. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2021, 30, 8872–8882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Peng, C.; Huang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Han, T.; Wang, G.; Wu, L.; Huang, G. Improving Mechanical Properties of Mg-Sc Alloy by Surface AZ31 Layer. Metals 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Li, J. Coupling the semi-solid treatment and hot extrusion to strengthen a Mg-Zn-Gd alloy containing I-phase. Mater. Lett. 2021, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bairagi, D.; Mandal, S. A comprehensive review on biocompatible Mg-based alloys as temporary orthopaedic implants: Current status, challenges, and future prospects. J. Magn. Alloy. 2022, 10, 627–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, S.; Zhong, S.; Yang, Q.; Yu, D.; Dai, Q.; Zhang, H.; Yin, L.; Wang, G.; Yao, Z. Transformation of Laves phases and its effect on the mechanical properties of TIG welded Mg-Al-Ca-Mn alloys. Journal of Materials Science & Technology 2022, 120, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, B.; Lu, L.; Kang, W.; Zhong, Y.; Ma, M.; Liu, L.; Wu, Z. Effect of Expansion Sphere Diameter on Deformation Behavior of AZ31 Mg Alloy during Extrusion. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2022, 31, 8512–8521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Mei, D.; Furushima, T.; Zhu, S.; Wang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Guan, S. In vitro corrosion properties of HTHEed Mg-Zn-Y-Nd alloy microtubes for stent applications: Influence of second phase particles and crystal orientation. J. Magn. Alloy. 2022, 10, 1286–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Pan, H.; Li, J.; Xie, D.; Zhang, D.; Che, C.; Meng, J.; Qin, G. Fabrication of exceptionally high-strength Mg-4Sm-0.6Zn-0.4Zr alloy via low-temperature extrusion. Materials Science and Engineering a-Structural Materials Properties Microstructure and Processing 2022, 833. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, J.; Qi, M.; Guo, W.; Deng, Y. A newly developed Mg-Zn-Gd-Mn-Sr alloy for degradable implant applications: Influence of extrusion temperature on microstructure, mechanical properties and in vitro corrosion behavior. Mater. Charact. 2022, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Wang, S.; Ge, C.; Yang, C.; Yang, Q.; Pan, H.; Qin, G. Effect of Ca content on microstructure and strength of as-extruded Mg-1.0Al-xCa alloy. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.J.; Yu, H.; Fan, S.D.; Kim, Y.M.; Park, S.H.; Zhao, W.M.; You, B.S.; Shin, K.S. A high-ductility extruded Mg-Bi-Ca alloy. Mater. Lett. 2020, 261, 127066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, M.; Huang, X.; Mabuchi, M.; Chino, Y. Compositional optimization of Mg–Zn–Sc sheet alloys for enhanced room temperature stretch formability. J. Alloys. Compd. 2020, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.G.; Xu, C.; Nakata, T.; Yan, H.; Chen, R.S.; Kamado, S. Enhancing strength and ductility of Mg-Zn-Gd alloy via slow-speed extrusion combined with pre-forging. J. Alloys. Compd. 2017, 694, 1214–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Y.; Yu, Z.P.; Zhang, L.; Liu, C.G.; Zha, M.; Wang, C.; Jiang, Q.C. Achieving high strength and high ductility in magnesium alloy using hard-plate rolling (HPR) process. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 17100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, W.J.; Hong, S.I.; Lee, J.M.; Kim, S.H. Dispersion of TiC particles in an in situ aluminum matrix composite by shear plastic flow during high-ratio differential speed rolling. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2013, 559, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.L.; Kang, S.B.; Cho, J.H. Influence of strain path on the microstructure evolution and mechanical properties in AM31 magnesium alloy sheets processed by differential speed rolling. Mate. Des. 2013, 44, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghdi, F.; Mahmudi, R.; Kang, J.Y.; Kim, H.S. Contributions of different strengthening mechanisms to the shear strength of an extruded Mg–4Zn–0. 5Ca alloy. Philos. Mag. 2015, 95, 3452–3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, B.; Li, B.; Lin, D.; Liao, Y. Enhanced room temperature stretch formability of AZ31B magnesium alloy sheet by laser shock peening. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 756, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.U.; Kim, S.-H.; Kim, Y.J.; Park, S.H. Improvement in bending formability of rolled magnesium alloy through precompression and subsequent annealing. J. Alloys. Compd. 2019, 787, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Mao, Y.; Fu, Y.; Jiang, B.; Xiong, K.; Zhang, S.; Pan, F. Improving the room-temperature formability of Mg-3Al-1Zn alloy sheet by introducing an orthogonal four-peak texture. J. Alloys. Compd. 2019, 797, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.; Huang, G.; Ma, L.; Wang, G.; Wang, L.; Pan, F. Evolution of microstructure and mechanical properties of AZ31 Mg alloy sheets processed by accumulated extrusion bonding with different relative orientation. J. Alloys. Compd. 2019, 784, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-Y.; Lu, L.-W.; Sheng, K.; Zhou, T. Microstructure and Texture Evolution During the Direct Extrusion and Bending–Shear Deformation of AZ31 Magnesium Alloy. Acta. Metall. Sin-Engl. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beygelzimer, Y.; Kulagin, R.; Estrin, Y.; Toth, L.S.; Kim, H.S.; Latypov, M.I. Twist Extrusion as a Potent Tool for Obtaining Advanced Engineering Materials: A Review. ADVANCED ENGINEERING MATERIALS 2017, 1600873, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zheng, R.; Chen, J.; Lyu, S.; Li, Y.; Xiao, W.; Ma, C. Significant improvement in the strength of Mg-Al-Zn-Ca-Mn extruded alloy by tailoring the initial microstructure. Vacuum 2019, 161, 429–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Nie, H.; Zhang, W.; Liang, W.; Wang, Y. Microstructural refinement and improvement of mechanical properties of hot-rolled Mg–3Al–Zn alloy sheets subjected to pre-extrusion and Al-Si alloying. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 722, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Xin, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Q. The texture dependence of strength in slip and twinning predominant deformations of Mg-3Al-1Zn alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 717, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.W.; Widiantara, I.P.; Ko, Y.G. Effect of deformation path on texture and tension properties of submicrocrystalline Al-Mg-Si alloy fabricated by differential speed rolling. Mater. Lett. 2018, 213, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.-C.; Cha, J.W.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, T.; Han, S.H.; Park, S.H. Improvement in tensile strength of extruded Mg-5Bi alloy through addition of Sn and its underlying strengthening mechanisms. J. Magn. Alloy. 2022, 10, 3100–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.T.; Kim, W.J. Critical review of superplastic magnesium alloys with emphasis on tensile elongation behavior and deformation mechanisms. J. Magn. Alloy. 2022, 10, 1133–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, H.; Tehrani, A.H.M.; Tehrani, M.; Heydari, M. Effect of extrusion process on microstructure and mechanical and corrosion properties of biodegradable Mg-5Zn-1.5Y magnesium alloy. International Journal of Minerals Metallurgy and Materials 2022, 29, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.; Song, Y.; Jiang, B.; Fu, J.; Jiang, Z.; Yang, Q.; Sheng, H.; Huang, G.; Zhang, D.; Pan, F. Comparison of microstructures and mechanical properties of composite extruded AZ31 sheets. J. Magn. Alloy. 2019, 7, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Mao, Y.; Gao, Y.; Xiong, K.; Jiang, B.; Pan, F. Effect of rolling paths and pass reductions on the microstructure and texture evolutions of AZ31 sheet with an initial asymmetrical texture distribution. J. Alloys. Compd. 2019, 786, 394–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Liu, W.; Chen, S.; Yang, Q.; Pan, F. Mechanical properties and microstructure of as-extruded AZ31 Mg alloy at high temperatures. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2011, 530, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Jiang, B.; Tian, Y.; Liu, W.; Pan, F. A tilted weak texture processed by an asymmetric extrusion for magnesium alloy sheets. Mater. Lett. 2013, 100, 29–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Jiang, B.; Zhou, G.; Dai, J.; Pan, F. Influence of an asymmetric shear deformation on microstructure evolution and mechanical behavior of AZ31 magnesium alloy sheet. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2014, 590, 440–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.-S.; Jiang, B.; Yu, Z.-J.; Dai, Q.-W.; Luo, S.-Q. Effect of Extrusion Strain Path on Microstructure and Properties of AZ31 Magnesium Alloy Sheet. Acta. Metall. Sin-Engl. 2015, 28, 1257–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Jiang, B.; He, J.; Song, B.; Liu, W.; Dong, H.; Pan, F. Tailoring texture and refining grain of magnesium alloy by differential speed extrusion process. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2014, 612, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yang, T.; Jiang, B.; Song, J.; He, J.; Wang, Q.; Chai, Y.; Huang, G.; Pan, F. Improved mechanical properties of Mg-3Al-1Zn alloy sheets by optimizing the extrusion die angles: Microstructural and texture evolution. J. Alloys. Compd. 2018, 762, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liu, W.; Jiang, B.; Yang, H.; Li, X.; Kang, Y.; Zhou, N.; Zhang, W.; Zheng, K.; Pan, F. Forming novel texture and enhancing the formability in Mg–3Al–Zn alloy sheets fabricated by transverse gradient extrusion. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2022, 18, 3143–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Song, J.; Jiang, B.; Tang, A.; Chai, Y.; Yang, T.; Huang, G.; Pan, F. An investigation on microstructure, texture and formability of AZ31 sheet processed by asymmetric porthole die extrusion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 720, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Shen, Y.; Jiang, B.; Tang, A.; Song, J.; Jiang, Z.; Yang, T.; Huang, G.; Pan, F. Enhanced stretch formability at room temperature for Mg-Al-Zn/Mg-Y laminated composite via porthole die extrusion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 731, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Jiang, B.; Kang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, W.; Zheng, K.; Pan, F. Tailoring microstructure and texture of Mg–3Al–1Zn alloy sheets through curve extrusion process for achieving low planar anisotropy. Journal of Materials Science & Technology 2022, 113, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Shi, O.L.; Jiang, B.; Quan, G.F.; Pan, F.S. Improved formability with theoretical critical shear strength transforming in Mg alloys with Sn addition. J. Alloys. Compd. 2018, 764, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Gu, R.; Chen, S.; Wang, W.; Wei, X. Effect of upper-die temperature on the formability of AZ31B magnesium alloy sheet in stamping. J. Mater. Process. Tech. 2018, 257, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ma, L.; Chai, S.; Zhang, W.; Chen, W.; Feng, Y.; Cui, G. Role of one direction strong texture in stretch formability for ZK60 magnesium alloy sheet. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 730, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Song, J.; Jiang, B.; He, J.; Wang, Q.; Liu, B.; Huang, G.; Pan, F. Effect of effective strain gradient on texture and mechanical properties of Mg-3Al-1Zn alloy sheets produced by asymmetric extrusion. Materials Science and Engineering a-Structural Materials Properties Microstructure and Processing 2017, 706, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.-Z.; Zha, M.; Wang, S.-Q.; Wang, S.-C.; Wang, C.; Jia, H.-L.; Wang, H.-Y. Alloying design and microstructural control strategies towards developing Mg alloys with enhanced ductility. J. Magn. Alloy. 2022, 10, 1191–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.S.; Jiang, B.; Dai, J.H.; Xiang, Q.; Pan, F.S. Microstructure and mechanical behaviour of asymmetric extruded Mg–3Al–1Zn alloy sheets. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2013, 29, 710–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.J.; Yoo, S.J.; Chen, Z.H.; Jeong, H.T. Grain size and texture control of Mg–3Al–1Zn alloy sheet using a combination of equal-channel angular rolling and high-speed-ratio differential speed-rolling processes. Scr. Mater. 2009, 60, 897–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Suzuki, K.; Watazu, A.; Shigematsu, I.; Saito, N. Microstructural and textural evolution of AZ31 magnesium alloy during differential speed rolling. J. Alloys. Compd. 2009, 479, 726–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, J.; Xiang, Q.; Xia, X.; Pan, F. Enhancement of mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of magnesium alloy sheet by pre-straining and annealing. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2015, 647, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Jiang, B.; Yang, Q.; Li, X.; Xia, X.; Pan, F. Influence of pre-hardening on microstructure evolution and mechanical behavior of AZ31 magnesium alloy sheet. J. Alloys. Compd. 2015, 621, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Jiang, B.; Yu, X.; Xu, J.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, B.; Pan, F. Strain path dependence of texture and property evolutions on rolled Mg-Li-Al-Zn alloy possessed of an asymmetric texture. J. Alloys. Compd. 2017, 698, 771–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Jiang, B.; Xu, J.; Zhang, J.; Yu, X.; Liu, B.; Pan, F. Effect of texture symmetry on mechanical performance and corrosion resistance of magnesium alloy sheet. J. Alloys. Compd. 2017, 723, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Wang, F.; Feng, M.; Jin, L.; Dong, J.; Wu, P. Mechanical behavior and microstructural evolution in rolled Mg-3Al-1Zn-0.5Mn alloy under large strain simple shear. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 712, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, D.; Rainforth, W.M.; Gao, J.; Sharp, J.; Wynne, B.; Ma, L. Individual effect of recrystallisation nucleation sites on texture weakening in a magnesium alloy: Part 1- double twins. Acta Mater. 2017, 135, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepeda-Jiménez, C.M.; Prado-Martínez, C.; Pérez-Prado, M.T. Understanding the high temperature reversed yield asymmetry in a Mg-rare earth alloy by slip trace analysis. Acta Mater. 2018, 145, 264–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Xu, C.; Hu, X.; Gan, W.; Wu, K.; Wang, X. Improving the Young's modulus of Mg via alloying and compositing - A short review. J. Magn. Alloy. 2022, 10, 2009–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Gonzalez, N.; Hidalgo-Manrique, P.; Garcia-Rodriguez, S.; Torres, B.; Rams, J. Effect of heat treatment on the mechanical and biocorrosion behaviour of two Mg-Zn-Ca alloys. J. Magn. Alloy. 2022, 10, 540–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.C.; Hu, J.; Nie, X.Y.; Li, H.X.; Du, Q.; Zhang, J.S.; Zhuang, L.Z. The interface bonding mechanism and related mechanical properties of Mg/Al compound materials fabricated by insert molding. Materials Science and Engineering a-Structural Materials Properties Microstructure and Processing 2015, 635, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.N.; Li, H.X.; Luo, J.R.; Liu, Y.J.; Du, Q.; Zhang, J.S. Interfacial bonding mechanism and mechanical properties of novel AZ31/WE43 bimetal composites fabricated by insert molding method. J. Alloys. Compd. 2017, 729, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.N.; Liu, J.C.; Nie, X.Y.; Li, Y.; Li, H.X.; Du, Q.; Zhuang, L.Z.; Zhang, J.S. Interface formation in magnesium-magnesium bimetal composites fabricated by insert molding method. Mate. Des. 2016, 91, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.B.; Chen, R.S.; Han, E.H. Preliminary investigations on the Mg-Al-Zn/Al laminated composite fabricated by equal channel angular extrusion. J. Mater. Process. Tech. 2009, 209, 4675–4681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wang, T.; Wu, R.; Hou, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, M. Effects of Annealing Process on the Interface of Alternate alpha/beta Mg-Li Composite Sheets Prepared by Accumulative Roll Bonding. J. Mater. Process. Tech. 2018, 254, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirumurugan, M.; Rao, S.A.; Kumaran, S.; Rao, T.S. Improved ductility in ZM21 magnesium-aluminium macrocomposite produced by co-extrusion. J. Mater. Process. Tech. 2011, 211, 1637–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negendank, M.; Mueller, S.; Reimers, W. Coextrusion of Mg-Al macro composites. J. Mater. Process. Tech. 2012, 212, 1954–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffari, A.; Manesh, H.D.; Janghorban, K. Evaluation of mechanical properties and structure of multilayered Al/Ni composites produced by accumulative roll bonding (ARB) process. J. Alloys. Compd. 2010, 489, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Hong, R.; Feng, B.; Yu, H.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Q. Fabrication of Mg/AL multilayer plates using an accumulative extrusion bonding process. Materials Science and Engineering a-Structural Materials Properties Microstructure and Processing 2015, 640, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Chen, R.-s.; Han, E.-h. Bonding interface zone of Mg-Gd-Y/Mg-Zn-Gd laminated composite fabricated by equal channel angular extrusion. Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China 2010, 20, S613–S618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Lv, S.; Yang, Q.; Qiu, X.; Yan, Z.; Duan, Q.; Meng, J. Multiplex intermetallic phases in a gravity die-cast Mg-6.0Zn-1.5Nd-0.5Zr (wt%) alloy. J. Magn. Alloy. 2022, 10, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luginin, N.A.; Eroshenko, A.Y.; Legostaeva, E.V.; Schmidt, J.; Tolmachev, A.I.; Uvarkin, P.V.; Sharkeev, Y.P. Effect of Severe Plastic Deformation by Extrusion on Microstructure and Physical and Mechanical Properties of Mg-Y-Nd and Mg-Ca Alloys. Technical Physics 2022, 67, 791–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, L.; Cai, S.; Li, Q.; Sun, J.; Bao, X.; Xu, G. Recent advances in hydrothermal modification of calcium phosphorus coating on magnesium alloy. J. Magn. Alloy. 2022, 10, 62–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Wang, J.; Yun, X.; Chen, Z. Fabrication of aluminum-magnesium clad composites by continuous extrusion. Materials Science and Engineering a-Structural Materials Properties Microstructure and Processing 2021, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; Li, Q.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, Z. Microstructure and texture evolution with Sm addition in extruded Mg-Gd-Sm-Zr alloy. Materials Research Express 2021, 8, 096523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).