Submitted:

20 June 2023

Posted:

21 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

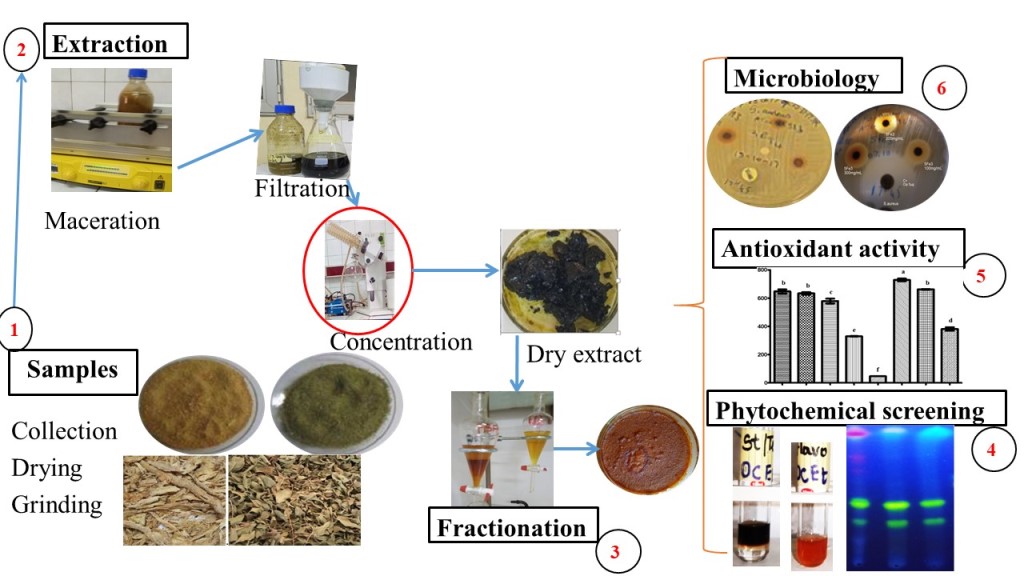

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant materials

2.2. Microbial strains

2.3. Culture media

2.4. Chemicals and Standards

2.5. Plant extracts preparation

- -

- Fractionation

2.6. Phytochemical Screening

2.6.1. Characterization reactions in tubes

- -

- Preparation of ethanolic extract solutions

- -

- Hydrolysis of extract solutions

- -

- Screening for Tannins

- -

- Screening for Flavonoids (Shibata or cyanidin reaction)

- -

- Screening for Leucoanthocyans

- -

- Screening for anthracenosides/anthraquinones (Bornträger reaction)

- -

- Screening for sterols and terpenoids (Liebermann Burchard Reaction)

- -

- Screening for coumarins and derivatives (Feigl reaction)

- -

- Screening for saponosides by the foam test

- -

- Screening for cardiotonic heterosides

- -

- Screening for reducing compounds

- -

- Screening for alkaloids

- -

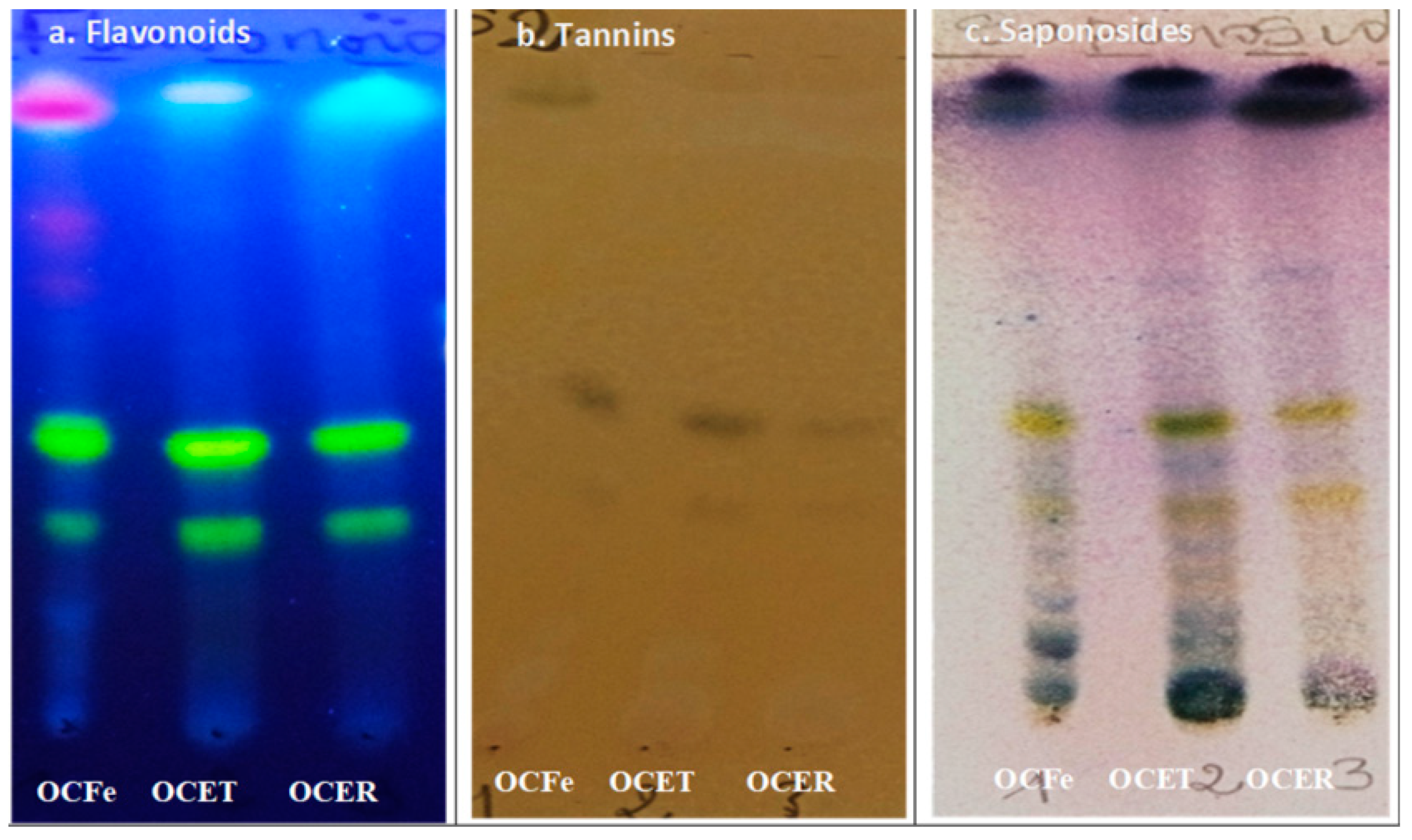

- Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC)

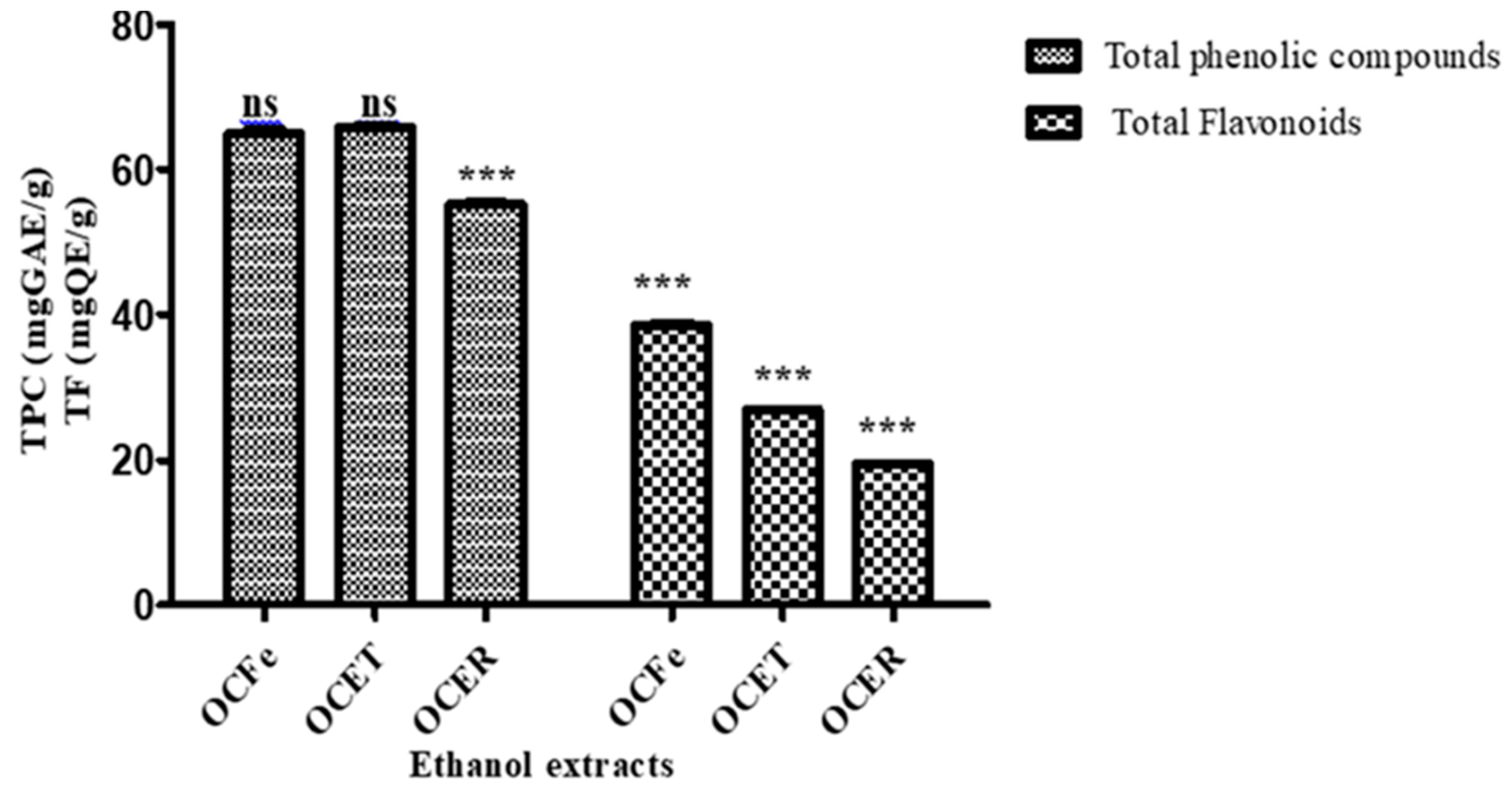

2.6.2. Quantitative phytochemical assessment

- -

- Determination of Total Phenolics: Folin-Ciocalteu Method

- -

- Determination of Total Flavonoids

2.7. Biological properties

2.7.1. In vitro antimicrobial assay

- -

- Disc method in Agar medium

- -

- Microdilution method

- -

- Interpreting antimicrobial test results

- -

- bactericidal extracts: BMC/MIC≤ 2

- -

- bacteriostatic extracts: BMC/MIC > 2

- -

- extracts with an inhibition diameter ≥10 mm ( selected for more investigation)

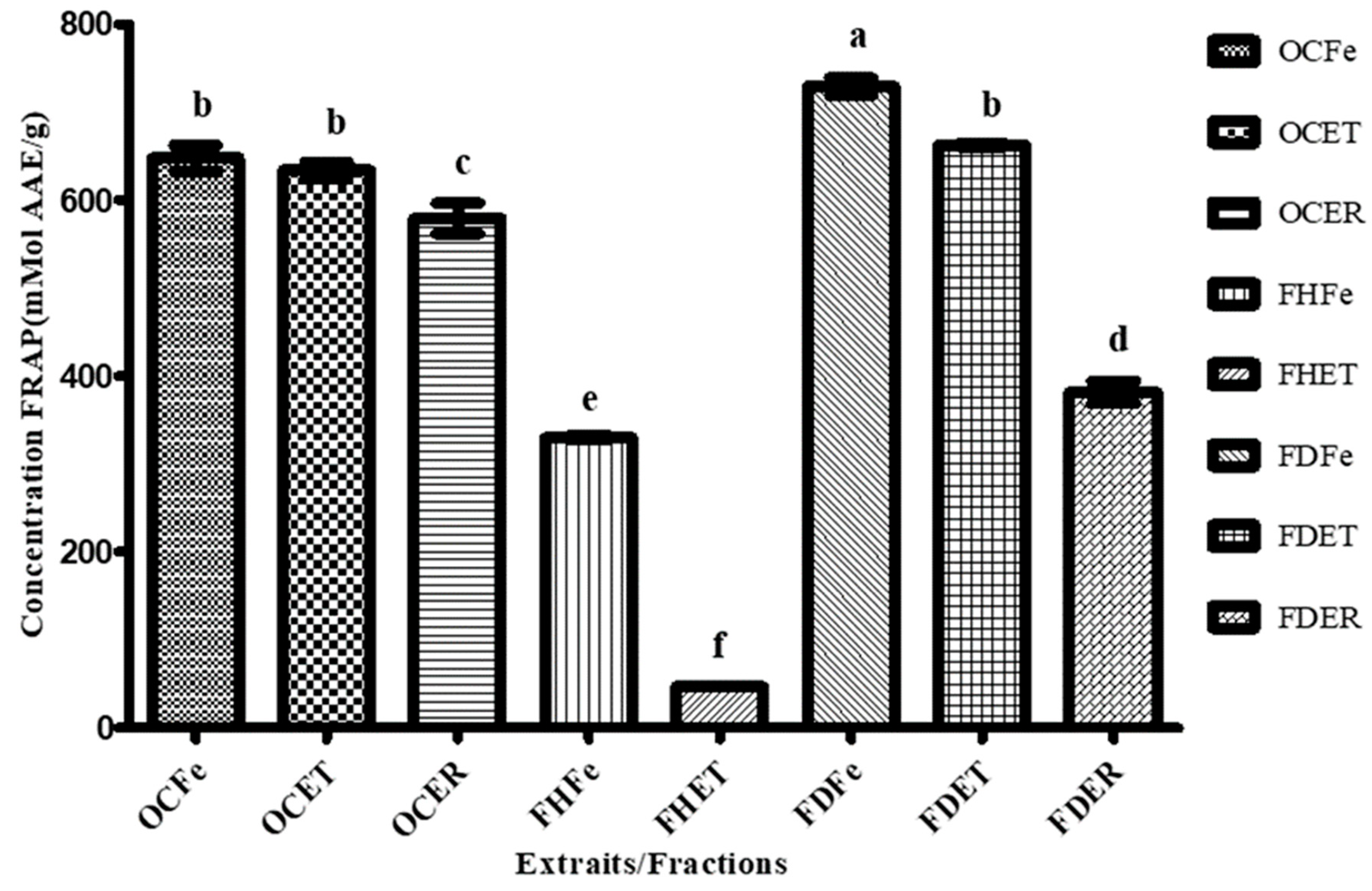

2.7.2. Antioxidant Activity Assays

- -

- ABTS Radical Cation Scavenging Activity

- -

- DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

- -

- FRAP Assay

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Phytochemical screening

- -

- Qualitative phytochemical screening

- -

- Quantitative phytochemical assessment

3.2. Antimicrobial activity

|

Strains Extracts |

Test | Pa | Ec | Sa | Sp | Sag | Ca | Ct |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC | D | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PC | D | 27.33 ± 0.57 | 35.67 ± 0.57 | 31.33 ± 1.15 | 35.67 ± 0.57 | 37.67 ± 0.57 | 20.67 ± 0.57 | 21 ± 1 |

| FHFe | D | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 ±0.3 | 13 ± 0.67 |

| FHET | D | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 ± 0 | 8 ± 0 | 11.5 ± 0 |

| FHER | D | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 ±0 | 8 ± 0 | 10 ± 0 |

| FDFe | D | 0 | 0 | 12 ± 0 | 15.2 ± 0.33 | 15.33 ± 1 | 0 | 0 |

| FDET | D | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 ± 1.12 | 15 ± 1.67 | 0 | 0 |

| FDER | D | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 ± 0 | 12 ± 0.33 | 0 | 0 |

| FaqER | D | 0 | 0 | 12.66 ± 0.28 | 14.5 ±0.5 | 14.5 ±0.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Extracts | MIC (mg/mL) | MBC (mg/mL) | MBC/MIC | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | ||||

| FDFe | 4.64 ± 0 | 9.28 ± 0 | 2 | Bactericidal |

| FaqER | 12.51 ± 2.02 | 25.03 ± 3.1 | 2 | Bactericidal |

| S. agalactiae | ||||

| FDFe | 2.03 ± 0 | 2.03 ± 0 | 1 | Bactericidal |

| FDET | 0.96 ± 0 | 0.96 ± 0 | 1 | Bactericidal |

| FaqER | 5.04 ± 0.9 | 10.08 ± 0.9 | 2 | Bactericidal |

| S. pyogenes | ||||

| FDFe | 2.03 ± 0 | 2.03 ± 0 | 1 | Bactericidal |

| FDET | 0.96 ± 0 | 0.96 ± 0 | 1 | Bactericidal |

| FaqER | 5.04 ± 0.9 | 10.08 ± 0.9 | 2 | Bactericidal |

| C. tropicalis | ||||

| FHFe | 0.23 ± 0 | 0.23 ± 0 | 1 | Bactericidal |

| FHER | 0.43 ± 0 | 0.43 ± 0 | 1 | Bactericidal |

| Extrait | ABTS | DPPH |

|---|---|---|

| IC50 (μg/mL) | IC50 (μg/mL) | |

| OCFe | 23.87a ± 0.21 | 715.88c ± 0.6 |

| OCET | 69.81d ± 0.31 | 990.33d ± 0,57 |

| OCER | 76.14e ± 0.79 | >1000d |

| FHFe | >1000h | >1000d |

| FHET | >853.69g ± 0.01 | >1000d |

| FHER | >1000h | >1000d |

| FDFe | 88.40f ± 0.30 | 463.33b ± 0.32 |

| FDET | 36.85b ± 0,52 | 383.33a ± 0,4 |

| FDER | 41.54c ± 0,18 | >1000d |

| Trolox | 3.78*** ± 0,0027 | 6.34***± 0.004 |

3.3. Antioxydant activity

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kandil, A. Prévalence des dermatoses en médecine communautaire à Marrakech. Thésis de médecine, Université Cadi Ayyad; 2021.

- Silva S, Negri M, Henriques M, Oliveira R, Williams DW, Azeredo J. Candida glabrata, Candida parapsilosis and Candida tropicalis: Biology, epidemiology, pathogenicity and antifungal resistance. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2012;36(2):288–305. [CrossRef]

- Esposito S, Noviello S, Leone S. Epidemiology and microbiology of skin and soft tissue infections. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2016;29(2):109–15. [CrossRef]

- Dione H, Bammo M, Lawson ATD, Seck F, Dioussé P, Guèye N, et al. Les urgences dermatologiques à l’hôpital régional de Thiès/Sénégal: une série de 240 cas. Rev Africaine Médecine Interne. 2018;5(1):11–4.

- Villeneuve, D. Quelle est l’épidémiologie de la dermatoporose dans une population de Médecine Générale en Île de France To cite this version: HAL Id: dumas-01732088 [Internet]. Université Paris Descartes; 2017. Available online: https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-01732088.

- Borda LJ, Louis SJ, Fethiere M, Dure D, Morrison BW. Prevalence of Skin Disease in Urban Haiti: A Cross-Sectional Study. Dermatology. 2019;235(6):495–500. [CrossRef]

- Abdoulaye O, Laouali Harouna Amadou M, Amadou O, Adakal O, Magagi Larwanou H, Boubou L, et al. Aspects épidémiologiques et bactériologiques des infections du site opératoire (ISO) dans les services de chirurgie à l’Hôpital National de Niamey (HNN). Pan Afr Med J. 2018;8688:1–5.

- Githiori JB, Höglund J, Waller PJ, Baker RL. Anthelmintic activity of preparations derived from Myrsine africana and Rapanea melanophloeos against the nematode parasite, Haemonchus contortus, of sheep. J Ethnopharmacol. 2002;80(2–3):187–91. [CrossRef]

- Saad B, Azaizeh H, Abu-Hijleh G, Said O. Safety of traditional Arab herbal medicine. Evidence-based Complement Altern Med. 2006;3(4):433–9. [CrossRef]

- Newman DJ, Cragg GM. Natural Products as Sources of New Drugs from 1981 to 2014. J Nat Prod. 2016;79(3):629–61. [CrossRef]

- Grønhaug TE, Ghildyal P, Barsett H, Michaelsen TE, Morris G, Diallo D, et al. Bioactive arabinogalactans from the leaves of Opilia celtidifolia Endl. ex Walp. (Opiliaceae). Glycobiology. 2010;20(12):1654–64. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann J, Gendrisch F, Schempp CM, Wölfle U. New herbal biomedicines for the topical treatment of dermatological disorders. Biomedicines. 2020;8(2). [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Rodríguez P, Baquero LP, Larrota HR. Flavonoids: Potential Therapeutic Agents by Their Antioxidant Capacity. In: Bioactive Compounds: Health Benefits and Potential Applications [Internet]. Elsevier Inc.; 2018. p. 265–88. [CrossRef]

- Górniak I, Bartoszewski R, Króliczewski J. Comprehensive review of antimicrobial activities of plant flavonoids. Phytochem Rev. 2019;18(1):241–72. [CrossRef]

- Zaid H, Silbermann M, Ben-Arye E, Saad B. Greco-Arab and Islamic herbal-derived anticancer modalities: From tradition to molecular mechanisms. Evidence-based Complement Altern Med. 2012;2012. [CrossRef]

- Papuc C, Goran G V., Predescu CN, Nicorescu V, Stefan G. Plant Polyphenols as Antioxidant and Antibacterial Agents for Shelf-Life Extension of Meat and Meat Products: Classification, Structures, Sources, and Action Mechanisms. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf [Internet]. 2017;00:1–26.

- Sawadogo WR, Lompo M, Guissou IP, Nacoulma OG. Dosage des triterpènes et steroïdes de Dicliptera verticillata et évaluation de leur activité anti-inflammatoire topique. Med Afr Noire. 2008;4:55–62.

- Le CT, Liu B, Barrett RL, Lu LM, Wen J, Chen ZD. Phylogeny and a new tribal classification of Opiliaceae (Santalales) based on molecular and morphological evidence. J Syst Evol. 2018;56(1):56–66. [CrossRef]

- Kasipandi M, Manikandan A, Sreeja PS, Suman T, Saikumar S, Dhivya S, et al. Effects of in vitro simulated gastrointestinal digestion on the antioxidant, α- glucosidase and α-amylase inhibitory activities of water-soluble polysaccharides from Opilia amentacea roxb fruit. LWT - Food Sci Technol [Internet]. 2019;111(May):774–81. [CrossRef]

- Owolabi MS, Omowonuola AA, Lawal OA, Dosoky NS, Collins JT, Ogungbe IV, et al. Phytochemical and bioactivity screening of six Nigerian medicinal plants. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2017;6(6):1430–7.

- ON Ouedraogo. Plantes médicinales et pratiques médicales traditionnelles au Burkina Faso: cas du Plateau central [Internet]. revues.cirad.fr. Université de Ouagadougou; 1996 [cited 2019 May 6]. Available online: http://revues.cirad.fr/index.php/BFT/article/view/20481.

- Dassou M, D. Gbenou J, A. Laleye A, A. Gbaguidi F (Université d’Abomey-C. Activité anticonvulsivant de Opilia celtidifolia (Guill et Perr) Opiliaceae, plante utilisée dans le traitement traditionnel de l’épilepsie au Benin. Conf Pap ·. 2020;7(April).

- Koala M, Ramde-Tiendrebeogo A, Ouedraogo N, Ilboudo S, Kaboré B, Kini FB, et al. HPTLC Phytochemical Screening and Hydrophilic Antioxidant Activities of Apium graveolens L., Cleome gynandra L., and Hibiscus sabdariffa L. Used for Diabetes Management. Am J Anal Chem. 2021;12(01):15–28. [CrossRef]

- Ponce AG, Fritz R, Del Valle C, Roura SI. Antimicrobial activity of essential oils on the native microflora of organic Swiss chard. LWT - Food Sci Technol. 2003;36(7):679–84. [CrossRef]

- Kuete, V. Potential of Cameroonian plants and derived products against microbial infections: A review. Planta Med. 2010;76(14):1479–91. [CrossRef]

- Marmonier, A. Introduction aux techniques d’étude des antibiotiques. Bactériologie Médicale, Tech usuelles. 1990;1:227–36.

- Bance A, Sourabié S, Compaoré S, Compaoré E, Belem-Kabre WLME, Ouedraogo V, et al. Therapeutic properties of aqueous extracts of leaves and stems bark of Prosopis africana (Guill. & Perr.) Taub. (Fabaceae) used in the management of dental caries. J Drug Deliv Ther. 2021;11(6):108–14. [CrossRef]

- Kaboré B, Koala M, Nitiema M, Ouedraogo WRC, Compaoré S, Belemnaba L, et al. Phytochemical Screening by High-Performance Thin-Layer Chromatography, Antioxidant Activities and Acute Toxicity of Trunk Barks Extracts of Lannea velutina A. Rich. Am J Anal Chem. 2022;13(10):365–81. [CrossRef]

- Paré Dramane, N’do Jotham Yhi-pênê, Hilou Adama. Phytochemical and biological investigation of 5 bioactive fractions of Caralluma acutangula, a medicinal plant used in traditional medicine in northern of Burkina Faso. GSC Biol Pharm Sci. 2020;11(3):081–91. [CrossRef]

- Koala M, Kaboré B, Rimwagna Ouedraogo CW, Belemnaba L, Nitiema M, Compaoré S, et al. High-Performance Thin-Layer Chromatography Phytochemical Profiling, Antioxidant Activities, and Acute Toxicity of Leaves Extracts of Lannea velutina A. Rich. J Med Chem Sci. 2023;6(2):410–23. [CrossRef]

- Koumare B, Diallo D, Sanogo R, Diarra B. Study of Phytochemistry and Appetizing Activity of Decocted Leaves of Opilia Celtidifolia guill . et perr . ( OPILIACEAE ) in Rats. EasyChair Prepr. 2020.

- Togola A, Karabinta K, Denou A, Haidara M, Sanogo R, Diallo D. Effet protecteur des feuilles de Opilia celtidifolia contre l’ulcère induit par l’éthanol chez le rat. Int J Biol Chem Sci. 2014;8(6):2416. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee KP, Houghton P. Regulation of herbal medicinal products. In: Pharmaceutical Journal. 2009. p. 485–6.

- Medini F, Fellah H, Ksouri R, Abdelly C. Total phenolic, flavonoid and tannin contents and antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of organic extracts of shoots of the plant. J Taiba Univ Sci [Internet]. 2014;8:216–24. [CrossRef]

- Tadić V, Oliva A, Božović M, Cipolla A, De Angelis M, Vullo V, et al. Chemical and antimicrobial analyses of Sideritis romana L. subsp. purpurea (Tal. ex Benth.) Heywood, an endemic of the Western Balkan. Molecules. 2017;22(9):1–15. [CrossRef]

- Slobodníková L, Fialová S, Rendeková K, Kováč J, Mučaji P. Antibiofilm activity of plant polyphenols. Molecules. 2016;21(12):1–15. [CrossRef]

- Kiessoun K, Arsène M, Yomalan K, Sytar O, Souza A, Brestic M, et al. In vitro antioxidant and anti-inflammatory profiles of bioactive fraction from Opilia celtidifolia (Guill. & Perr.) Endl. Ex walp (Opiliaceae). World J Pharm Res [Internet]. 2019;8(1):141–56. Available online: www.wjpr.net. [CrossRef]

- Jaakola L, Määttä-Riihinen K, Kärenlampi S, Hohtola A. Activation of flavonoid biosynthesis by solar radiation in bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.) leaves. Planta. 2004;218(5):721–8. [CrossRef]

- Youl O, Yougbare S, Lompo P, Yaro B, Tahita CM, Tinto H, et al. Preliminary screening of the antimicrobial activity of nine medicinal plant species from Burkina Faso. J Med Plants Res. 2021;15(11):522–30. [CrossRef]

- Gyawali R, Ibrahim SA. Natural products as antimicrobial agents. Food Control [Internet]. 2014;46:412–29. [CrossRef]

- Daglia, M. Polyphenols as antimicrobial agents. Curr Opin Biotechnol [Internet]. 2012;23(2):174–81. [CrossRef]

- Cushnie TPT, Lamb AJ. Recent advances in understanding the antibacterial properties of flavonoids. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2011;38(2):99–107. [CrossRef]

- Habbal O, Hasson SS, El-Hag AH, Al-Mahrooqi Z, Al-Hashmi N, Al-Bimani Z, et al. Antibacterial activity of Lawsonia inermis Linn (Henna) against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed [Internet]. 2011;1(3):173–6. [CrossRef]

- Naz S, Siddiqi R, Ahmad S, Rasool SA, Sayeed SA. Antibacterial activity directed isolation of compounds from Punica granatum. J Food Sci. 2007;72(9). [CrossRef]

- Magid AA, Abdellah A, Pecher V, Pasquier L, Harakat D, Voutquenne-Nazabadioko L. Flavonol glycosides and lignans from the leaves of Opilia amentacea. Phytochem Lett [Internet]. 2017;21(May):84–9. [CrossRef]

- Konaté K, Yomalan K, Sytar O, Zerbo P, Brestic M, Patrick VD, et al. Free radicals scavenging capacity, antidiabetic and antihypertensive activities of flavonoid-rich fractions from leaves of Trichilia emetica and opilia amentacea in an animal model of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Evidence-based Complement Altern Med. 2014;2014. [CrossRef]

- Shah M, Parveen Z, Khan MR. Evaluation of antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, analgesic and antipyretic activities of the stem bark of Sapindus mukorossi. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;17(1):1–16. [CrossRef]

- Parikh B, Patel VH. Quantification of phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity of an underutilized Indian fruit: Rayan [Manilkara hexandra (Roxb.) Dubard]. Food Sci Hum Wellness [Internet]. 2017;6(1):10–9. [CrossRef]

- Ling LT, Radhakrishnan AK, Subramaniam T, Cheng HM, Palanisamy UD. Assessment of antioxidant capacity and cytotoxicity of selected malaysian plants. Molecules. 2010;15(4):2139–51. [CrossRef]

- Kada, S. Recherche d’extraits de plantes médicinales doués d ’ activités biologiques. Thèse Dr en Sci Biol. 2018;172.

- Beddou, M.F. Etude phytochimique et activités biologiques de deux plantes médicinales sahariennes Rumex vesicarius L. et Anvillea radiata Coss. & Dur. Université Abou Bekr Belkaid; 2015.

- Meng Q, Yang Z, Jie G, Gao Y, Zhang X, Li W, et al. Evaluation of Antioxidant Activity of Tea Polyphenols by a Quantum Chemistry Calculation Method - PM6. J Food Nutr Res. 2014;2(12):965–72. [CrossRef]

| Microbial group | Strains | Incubation in oven |

|---|---|---|

| Gram negative bacilli | Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 | Incubation of inoculated agar plates for 24 hours at 37°C |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27653 | ||

| Gram positive cocci | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923 | |

| Streptococcus pyogenes ATCC 19615 | The inoculated agar plates were initially placed in moist, CO2-rich jars and incubated for 24-48 hours at 37°C | |

| Streptococcus agalactiae ATCC 13813 | ||

| Fungies | Candida albicans ATCC 90028 | Incubation for 48 hours at 25°C |

| Candida tropicalis ATCC 750 |

| Sample Phytochemical groups |

OCFe | OCET | OCER |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steroidal and triterpenic glycosides (saponosides) | (+) | (+) | (+) |

| Anthraquinones | (+) | (-) | (+) |

| Anthocyans | (-) | (-) | (-) |

| Alkaloids | (-) | (-) | (-) |

| Flavonoids | (+) | + | (+) |

| Coumarins and derivatives | (+) | (-) | (+) |

| Tannins | (+) | (+) | (+) |

| Reducing compounds | (+) | (+) | (+) |

| Cardenolids | (-) | (-) | (-) |

| P | CPT | CFT | IC50ABTS | IC50DPPH | IC50FRAP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPT | 1 | 0.749* | -0.534 | -0.458 | 0.919** |

| CFT | 1 | -0.959** | -0.931** | 0.932** | |

| IC50ABTS | 1 | 0.503** | -0.798** | ||

| IC50DPPH | 1 | -0.630** | |||

| IC50FRAP | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).