1. Introduction

Food safety remains a public health priority and a global responsibility of the governments of EU countries in their politics and long-term strategies [

1,

2,

3]. Moreover, food safety is intensively discussed in the current context of climate change [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. In an effort to minimize the contribution to global greenhouse gas emissions (GHG), food systems are undergoing some radical changes that will directly affect the field of food safety [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. The move toward more sustainable food and agriculture presents new challenges not only for food risk assessors, but also for managers and the general public, which is composed of consumers [

14]. Before the new challenges of future food systems can be addressed by redesigning food safety assessment strategies, it is essential to review and improve certain aspects that still affect the understanding of ‘food risk analysis’ as a whole [

15]. Of particular importance in this case is risk communication and, concomitantly, a clear understanding of the specific terminology used in risk assessment and management [

16,

17].

The terms ”hazard” and ”risk”, in the context of food safety, first appeared more than 20 years ago in the Codex Alimentarius, then in Regulation (EC) No. 178/2002 [

18] and other European Union regulations that are part of food law. Unfortunately, the distinction between these two has always been problematic [

19]. There is a minimal number of studies on this topic, of which very few related to food safety. In an empirical study, Scheer et al. (2014) [

20] concludes that “hazard” and “risk” are perceived very differently depending on the perspective of the stakeholders, regardless of their definition in the Codex Alimentarius [

21]. Moreover, an online survey by Wiedemann et al. (2010) [

22] revealed that numerous people cannot distinguish between the two notions, but rather mix hazard and risk aspects. In studies which are not related to food safety, the same issue appears, indicating the exercise of differentiating between “hazard” and ‘risk’ is not an easy one. In 2020, Freudenstein et al. [

23], concluded that risk communication needs to develop means for empowering the public to differentiate between hazards and risks after an online survey on the topic radiofrequency electromagnetic fields (RF EMF) and health. In the subsequent years, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has repeatedly urged a distinction between the two terms [

24,

25].

In accordance with the Codex Alimentarius, the General Food Law Regulation (EC) No. 178/2002, adopted by the European Parliament and the Council, defined the two terms as follows:

- ➢

”Hazard” is a biological, chemical or physical substance in, or a condition of a food or feed that may have an adverse effect on health;

- ➢

”Risk” is a function of the probability of an adverse health effect and the severity of that effect resulting from a hazard.

- ➢

These definitions are also reproduced in Regulation (EU) 2017/625 [

26] with minor changes that do not effect the intended meaning, as follows:

- ➢

”Hazard” means an agent or condition that may have potentially harmful effects on human, animal or plant health, animal welfare or the environment;

- ➢

”Risk” is a function of the likelihood of an adverse health effect on human, animal, or plant health, animal welfare, or the environment and the severity of that effect resulting from a hazard.

In the European Community (EC) the definitions of “hazard” and ”risk” should be uniformly adopted in national legislation. The message conveyed by legal documents must be unambiguous and leave no room for interpretation [

27]. Risk communication in this form should minimise consumer confusion, promote understanding of risk assessment and risk management, and increase public confidence in food quality and safety measures [

28]. Currently, food regulations adopted in English by the EC are translated into national languages, hence translations can be inconsistent. This is because either there are no appropriate expressions in other languages to distinguish between ”hazard” and ”risk” [

29,

30] or simply because translators themselves misunderstand the terminology.

The aim of this study is to identify, compare, and critically analyse the terms “hazard” and “risk” in the original English versions of some important food regulations (EU) 2002/178; (EU) 2004/852 [

31]; (EU) 2004/853 [

32]; (EU) 2017/625; (EU) 2019/1381 [

33] and their equivalents in the official EU languages. We also compare the most recent regulation with the oldest in terms of the number of discrepancies confirmed by us and by experts. The analysis of the current state of official regulations will allow policy-makers to plan further awareness-raising activities in EU Member States in order to introduce correct terminology.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection of Regulations

Several EU food regulations were screened to find the most relevant to food safety, which include risk assessment terminology. These are, for example, hazard, risk, hazard analysis, risk assessment, risk analysis. Based on this criterion and their undeniable importance in practice, the following food regulations were selected: Regulation (EU) 2002/178 on general principles and requirements of food law, Regulation (EU) 2004/852 on food hygiene, Regulation (EU) 2004/853 on specific hygiene rules for food of animal origin, Regulation (EU) 2017/625 on official controls and other official activities performed to ensure the application of food and feed law, rules on animal health and welfare, plant health and plant protection products, and the single version of Regulation (EU) 2019/1381 on the transparency and sustainability of EU risk assessment in the food chain. All regulations are publicly available on EUR-Lex, the official website for European Union law [

34]. With the exception of Regulation (EU) 1381/2019, which was available in a single version, an original act and the latest versions were extracted for each regulation. The most recent versions or new versions at the time of the search were as follows: 26/05/2021 version of Regulation (EU) 2002/178, 24/03/2021 version of Regulation (EU) 2004/852, 28/10/2021 version of Regulation (EU) 2004/853, 28/10/2021 version of Regulation (EU) 2017/625). In the comparison between the old and new versions of the document, the so called legal act was considered the old version. The purpose of this comparison was to examine improvements in the translation of “hazard”, “risk” and related constructions such as “hazard analysis”, ”risk assessment” and ”risk analysis”.

2.2. Software Development

A software tool HA-RI was developed in Java (Spring Framework) to compare two regulations, one in English and one in another language, to find inconsistent translations of “hazard” and “risk” or other structures related to food risk assessment: Risk Assessment, Risk Analysis, Hazard Analysis. The tool was the solution for quick screening of multiple food regulations and their document versions. The tool was developed for individual use, but permission to access can be granted to users upon requests. For more details on the development and features, see Supplementary Material 1.

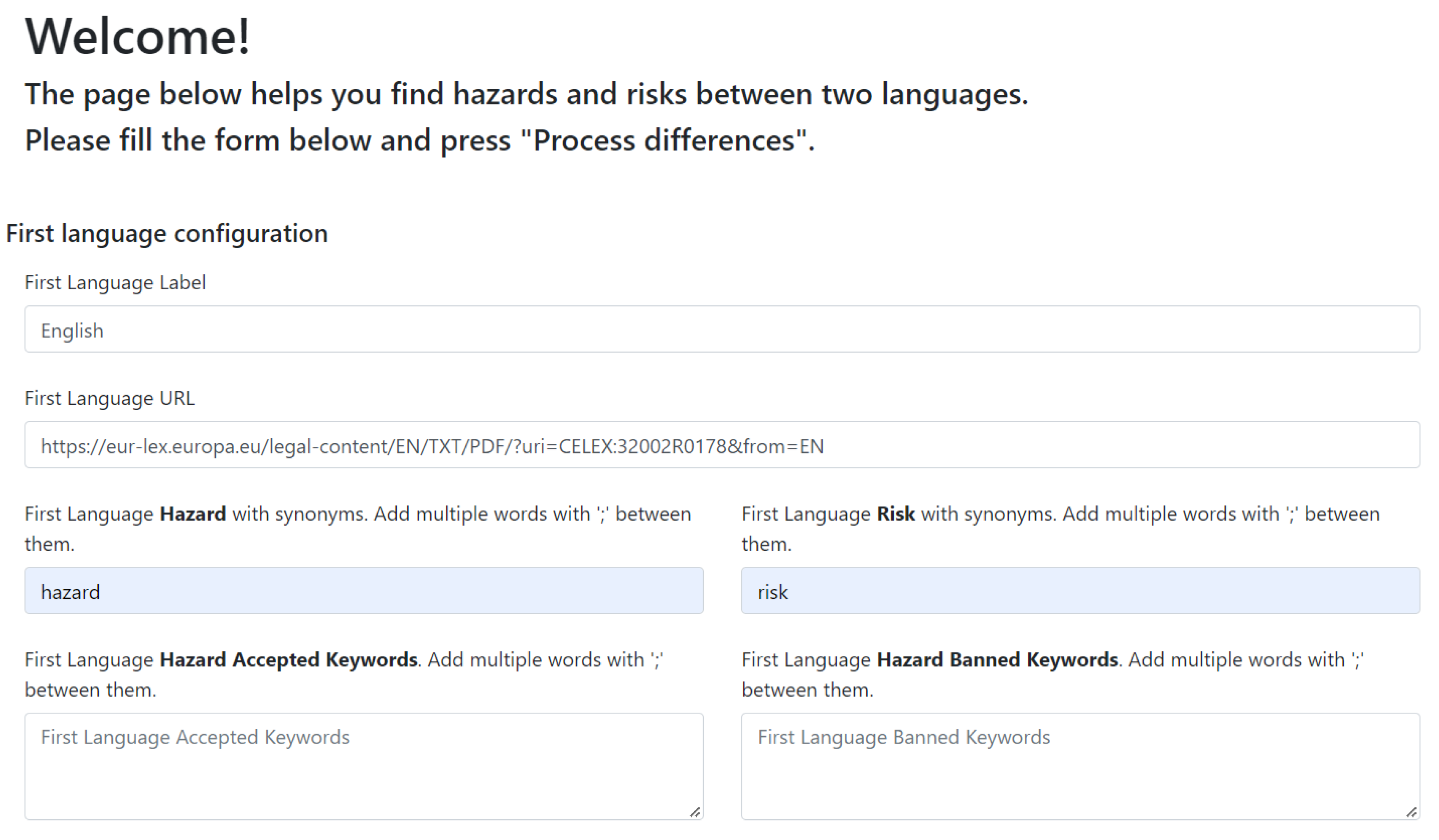

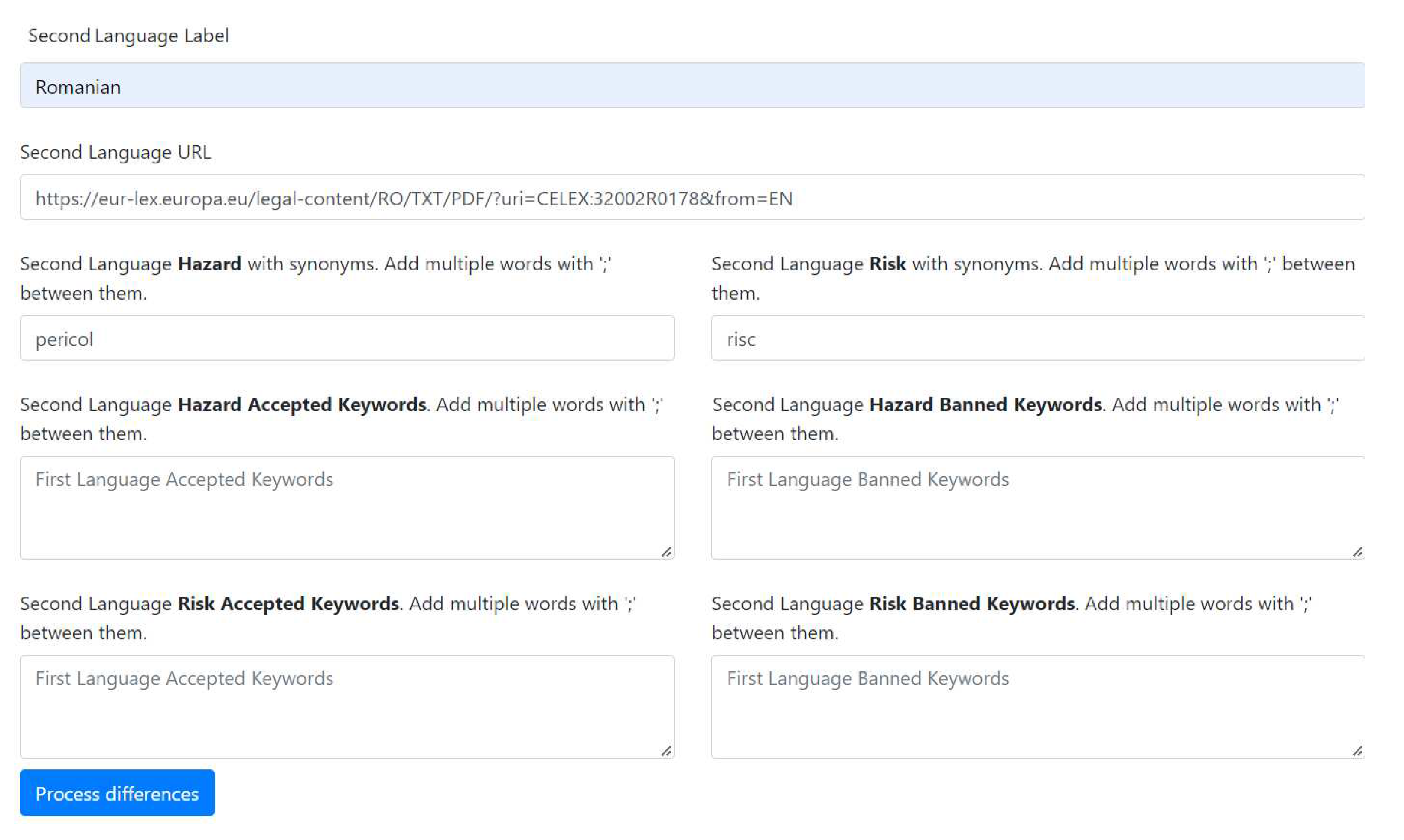

2.2.1. Creation of inconsistency tables for the EU languages

The input data for the software tool HA-RI were the first (in this case English) and second language, the URL address of the selected legislation for the first and second language and the words for hazard and risk for both selected languages. The form for entering the data into the program is shown in

Figure 1.

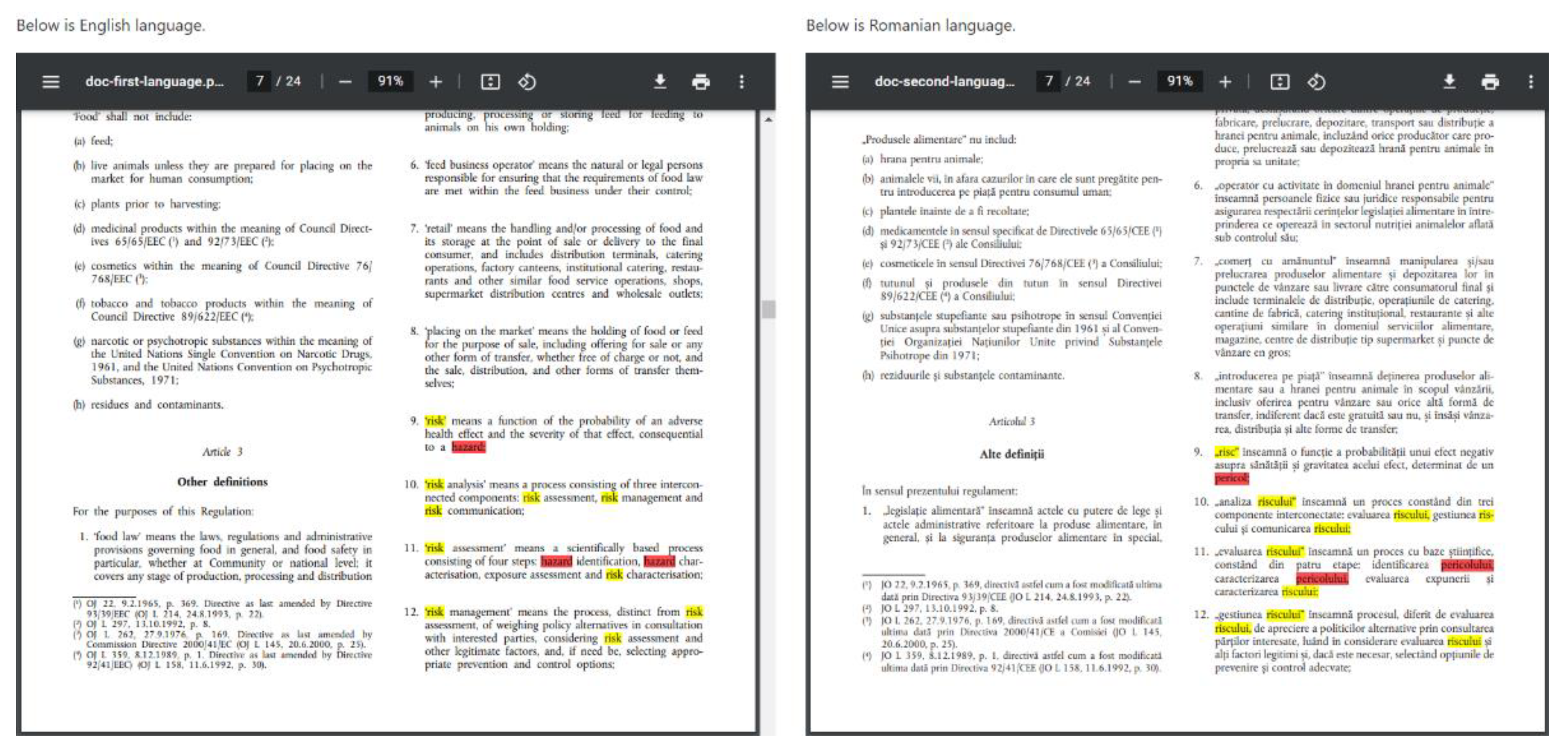

Figure 2 shows the part of the output document in PDF format where all inconsistencies and consistencies are marked in red and yellow, respectively. Finally, the tables of inconsistencies were created in Excel in a form suitable for statistical analysis and graphical representation.

2.3. Input from Food Expert

In January 2022, lists of inconsistencies in legislations due to translations were formulated. The first invitation to experts who were supposed to comment on these inconsistencies was sent to native speakers of various official EU languages. The reason for requesting their assistance was the fact that we, the authors of the presented study, are native speakers of Romanian (RO) and Slovenian (SL) and might thus have different opinions when analyzing inconsistencies in the translation of “hazard” and “risk” between English and other official EU languages. The validation or invalidation of our results was therefore considered useful and crucial for the interpretation of the final result.

The request was addressed to experts with different backgrounds (e.g., veterinarians, food technologists, nutritionists, biologists, etc.) trained or active in food risk assessment and communication. The expert group was composed of EU-FORA (Food Risk Assessment Programme, EFSA) Cycle 2021-2022, EU-FORA alumni from previous cohorts, representatives from EFSA Focal Points, and other proposed experts. At least one expert with native language in the following main EU languages had to accept our invitation: Bulgarian (BG), Czech (CS), Spanish (ES), Danish (DA), German (DE), Estonian (ET), Greek (EL), French (FR), Croatian (HR), Italian (IT), Latvian (LV), Lithuanian (LT), Hungarian (HU), Dutch (NL), Polish (PL), Portuguese (PT), Romanian (RO), Slovak (SK), Slovenian (SL), Finnish (FI), and Swedish (SV). No expert in Maltese was available at the time of the study. We performed the inconsistencies assessment for all 23 EU languages, and our opinion was the only one given for Romanian (RO) and Slovene (SL) inconsistencies. In total, the opinions of twenty-seven experts for 22 EU languages were included in the present study.

2.4. Analysis

First, the experts provided synonyms for “hazard”, “risk”, and related structures in their own languages (Supplementary Material 2). Second, the selected regulations were reviewed by HA-RI. The act in English of each selected regulation was compared with the corresponding version in BG, CS, ES, DA, DE, ET, EL, FR, HR, IT, LV, LT, HU, NL, PL, PT, RO, SK, SL, FI, SV. The same was applied to the document versions mentioned in section 2.1.

After screening, the results were recorded and the surveys were prepared as tables in Excel for the native experts. The inconsistencies to be discussed with the native experts were very specific and related to particular paragraphs of food legislation where deviations from the correct translation were found. For each inconsistency, the exact location in the legislation was provided by page and paragraph so that it could be easily verified in the case. An observation in the form of an objective question to the native speaker (e.g., “Is ‘hazard’ translated as ‘risk’?”, etc) to obtain his or her response was provided (Supplementary Material 3). Different combinations of terms lead to selected inconsistencies, e.g., H-R is when, “risk” is used instead of “hazard” (

Table 1).

Our opinion was not included in the survey to obtain an objective response from the experts.

To quantify the results, a scoring system for the responses was introduced. The quantitative codes ranged from 1 to 5, as explained in

Table 2. The inconsistencies found by us were marked with 5. Our definition of terms was based on Regulation (EU) 2002/178 and Regulation (EU) 2017/625, as well as synonyms previously provided by the experts. The experts’ response ranged from 1 to 5 (Supplementary Material 4). If more than one expert responded for the same language, the individual responses were not compared but their common reply as average value of their individual scores.

First, the results were to show the total number of inconsistencies between the old and the new version of the regulations. Only the inconsistencies identified by us and confirmed by the experts were considered. To get a clear idea of where these agreed inconsistencies are located at the level of the regulations, a pivot table was created (Supplementary Material 5).

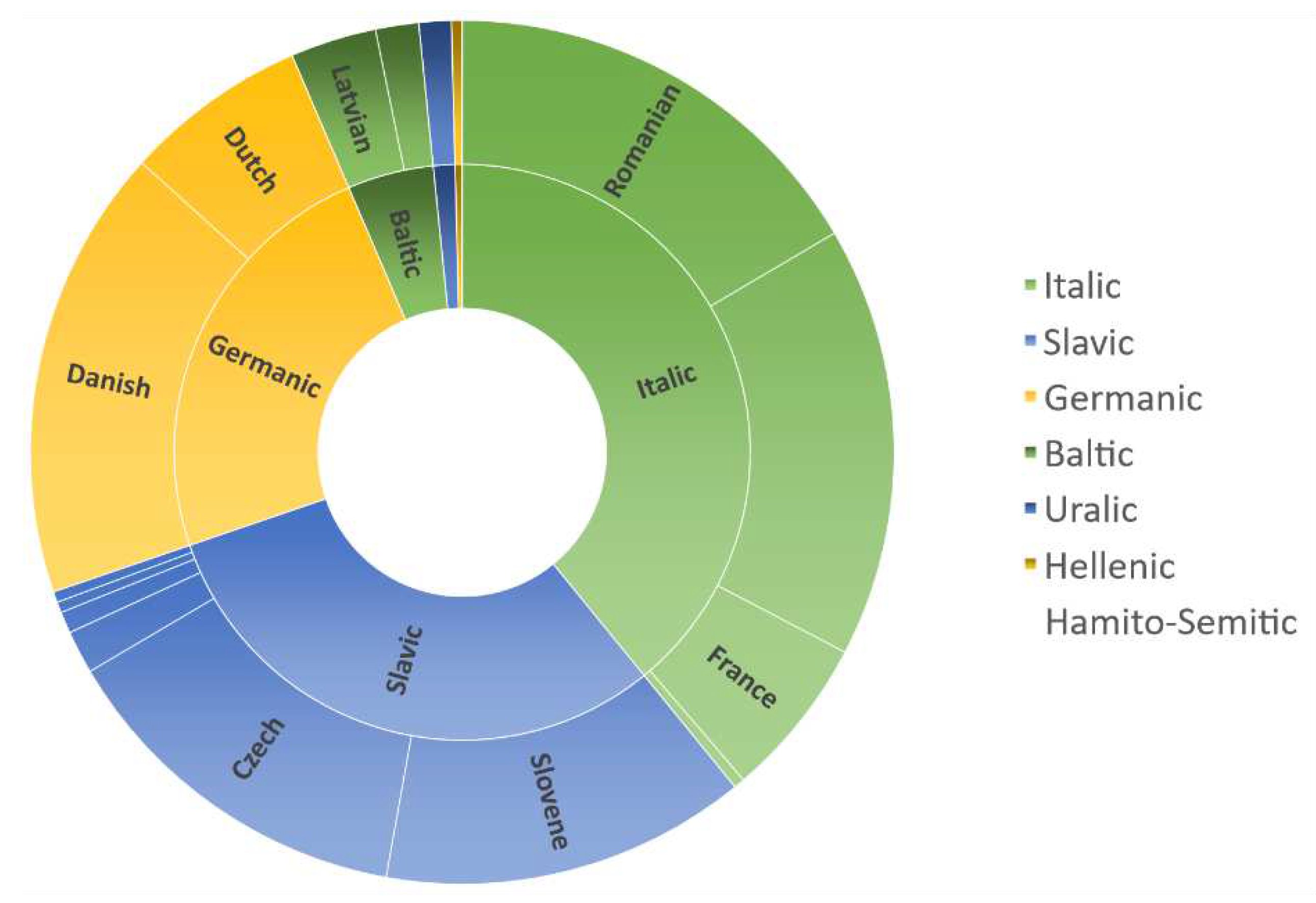

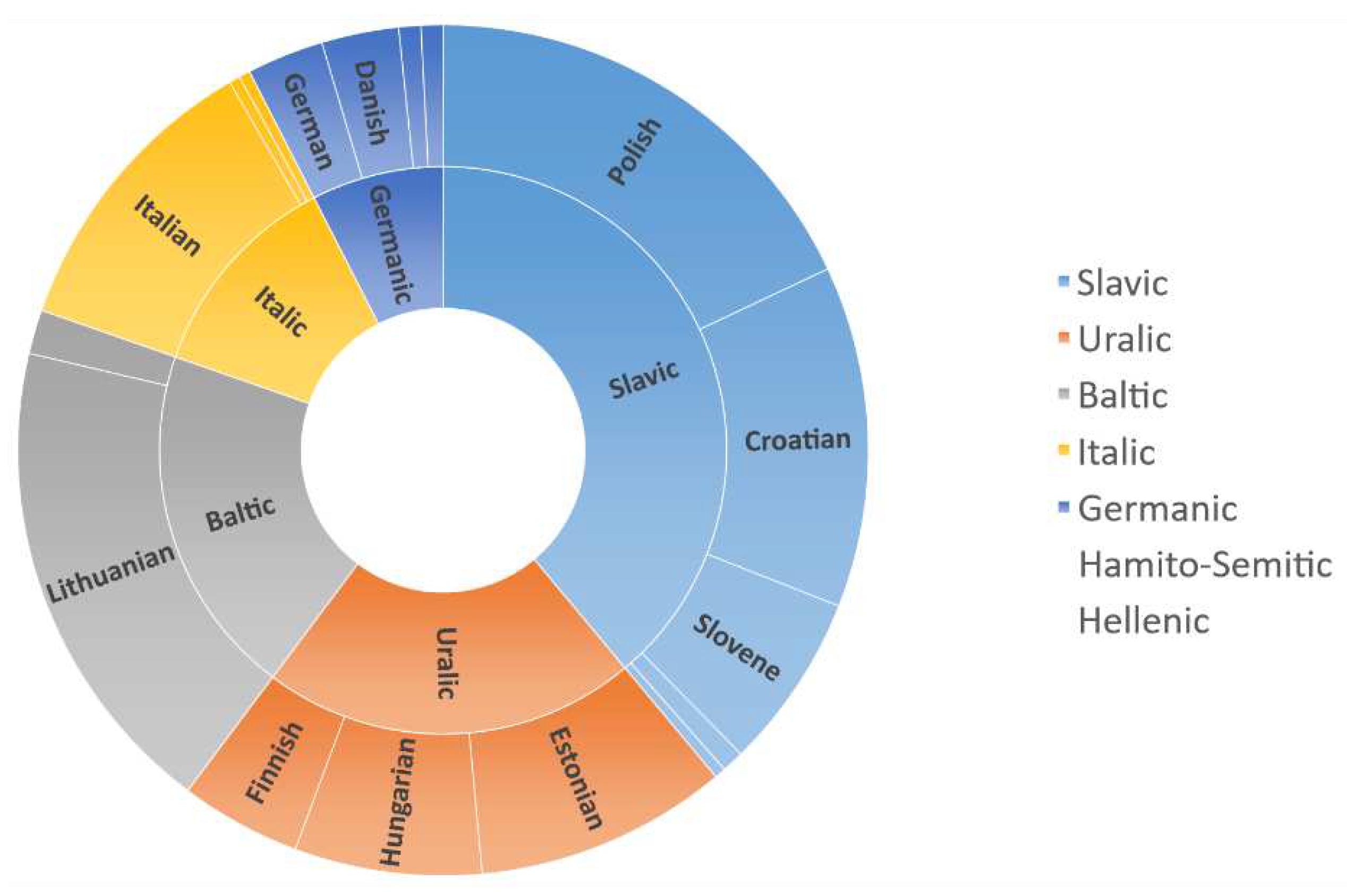

Second, the analysis of the results allowed the comparison between all subfamilies/ groups of EU languages (

Table 3) in terms of overall inconsistencies. Finally, correlations were made using the criteria in

Table 4.

The vast majority of EU languages belong to the Indo-European language family. The three main subfamilies are Germanic, Romance, and Slavic. The others are Baltic, Celtic, Hellenic and Uralic. Maltese is a special language. It is a Central Semitic language, derived from late medieval Sicilian Arabic with Romance overlays, spoken by the Maltese people. It is the national language of Malta and the only official Semitic language in the European Union.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Given the ordinal variables, a Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was calculated. For this purpose, the variables were coded (

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4). The variable ‘’agreement’’ was introduced to determine the agreement between our assessment and the experts (

Table 2 and

Table 3). Statistical calculations about expert confirmed inconsistencies were performed for the old version of Regulations (EU) 2002/178, 2004/852, 2004/853, 2017/625, the new version of the same regulations and the regulation (EU) 2019/1381. The relationship was considered significant when the p value was less than 0.05.

Comparisons between selected ordinal variables were performed using the Kruskal-Wallis test. The statistically significant difference was confirmed when the p value was less than 0.05.

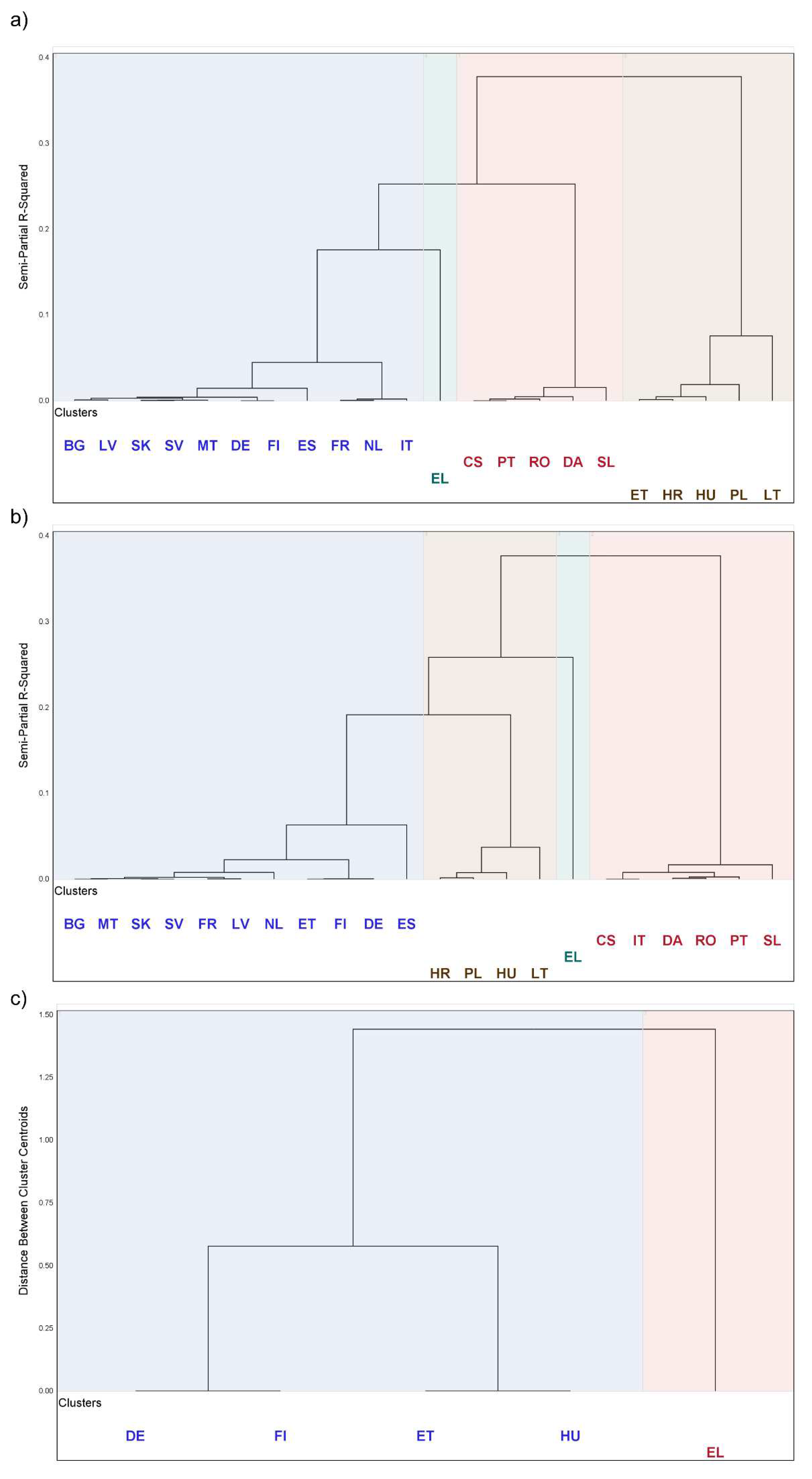

2.6. Clustering

Finally, a clustering of languages by the number of inconsistencies was performed. The selected variables were: R-H, H-RF, RA-RD, H-SD, and H-R (shown in

Table 1). After optimization, we selected the hierarchical Ward method for clustering, except for Regulation (EU) 1381/2019, where the average (

Figure 8) and the centroid hierarchical method (

Figure A3) were used.

The Cubic Clustering Criterion (CCC) [

35] was used to determine the number of clusters. When CCC was greater than 2, the number of clusters was relevant (groups of languages that are well separated). The clusters were represented by dendrograms.

Codes written in SAS for Windows were used for the graphical representations (bars and pies), comparison tests, clustering, and dendrograms (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, U. Sas® 9.4. SAS Inst. Inc., Cary, NC, USA 2017).

3. Results

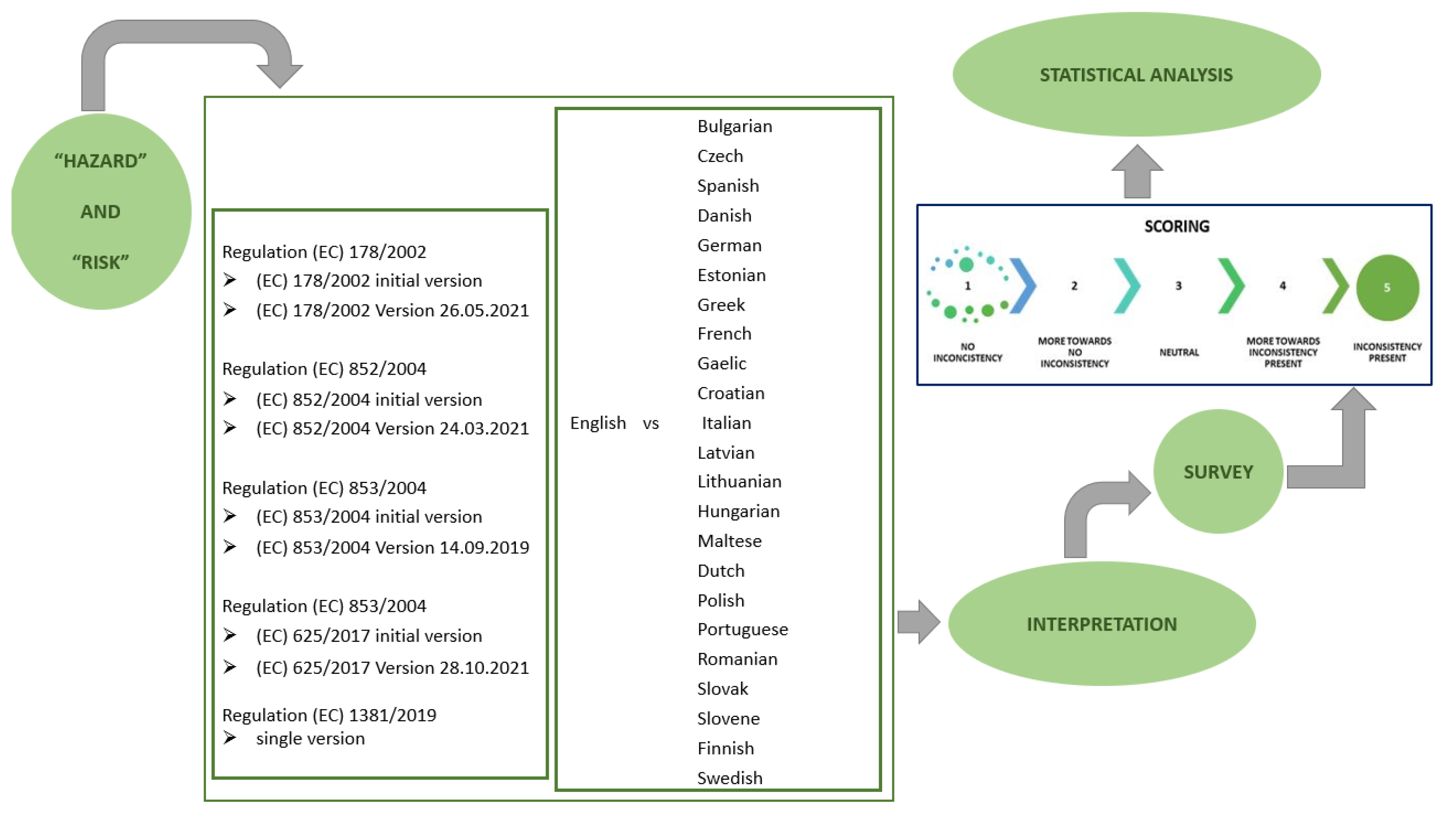

To perform the analysis of ‘’hazard’’ and ‘’risk’’ use in existing food legislation, a six step procedure was followed (

Figure 3). Upon selection of relevant regulations, languages and experts, HA-RI software tool was applied to create an initial list of inconsistencies for selected regulations and languages. These lists of inconsistencies were evaluated by us and experts.

The English language was the language of reference. The Gaelic language had no inconsistencies. The total number of the selected five types of inconsistencies (R-H, H-RF, RA-RD, H-SD, H-R, explained in

Table 1) that we identified was 657, of which 361 (54.95 %) were in the older version, 288 (43.84 %) in the newer version, and 8 (1.21 %) in Regulation (EU) 2019/1381. A total of 610 inconsistencies or 92.84 % were agreed between us and experts, of which 336 (55.08 %) were in the older version, 267 (43.77 %) in the newer version, and 7 (1.15 %) in Regulation (EU) 2019/1381 (

Table 5).

In most cases our observations on the inconsistencies and awarded scores (

Table 2) were confirmed by the native experts. However, there were a few cases where the experts found the use of “hazard” and “risk” as synonyms acceptable for reasons of linguistic freedom (

Table 3;

Table 5). For example, for the Slovak language for the new regulation, 4 inconsistencies were identified, but only 2 were confirmed by the experts (

Table 5).

The substitution of word "hazard" with the word "risk" was most frequently observed in the Italic group, followed by the Slavic, Germanic and Baltic groups (

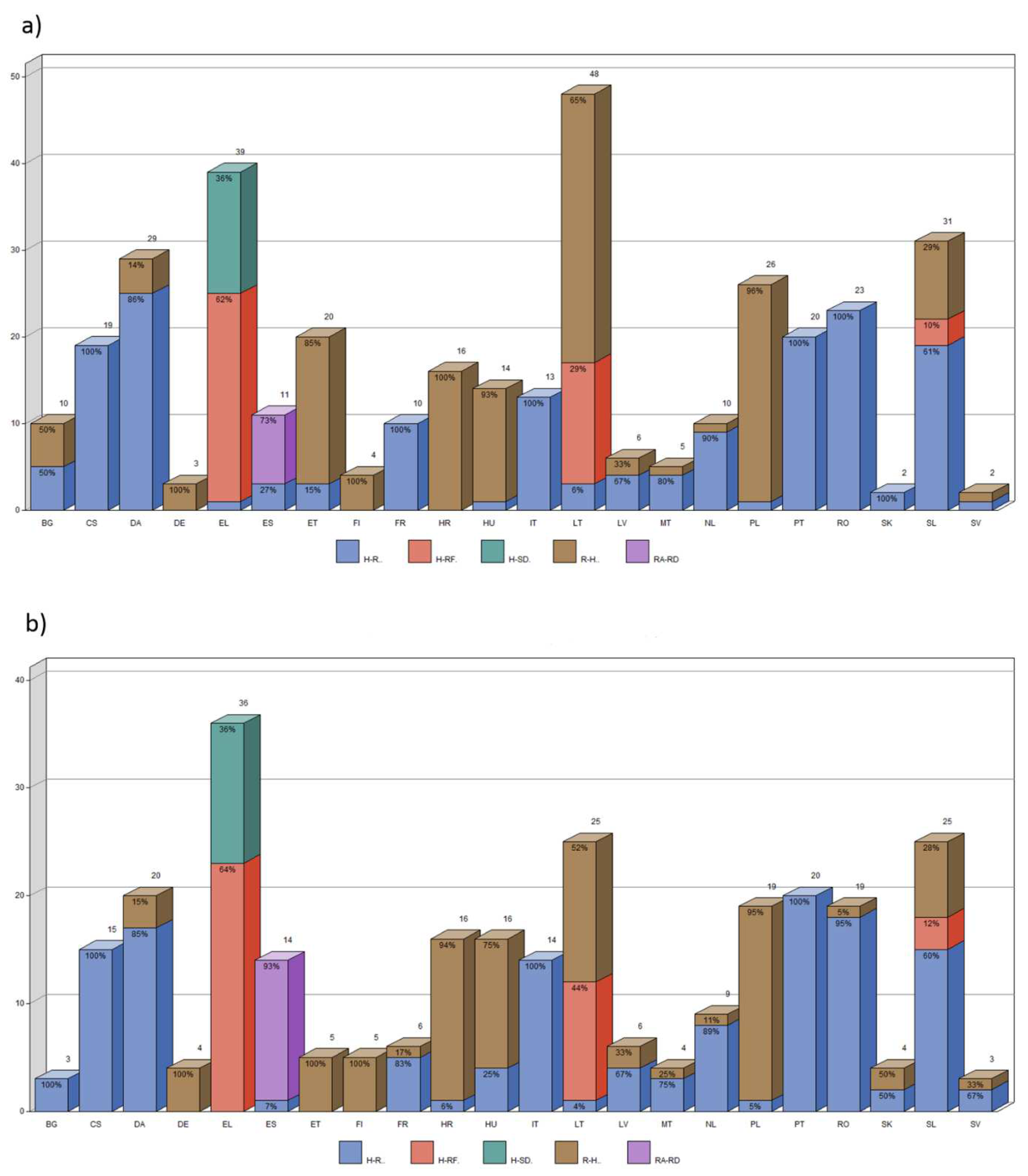

Figure 4). In other language groups such as Hamito-Semitic, Uralic and Hellenic, the mentioned substitution was rare.

Substitution of the word “risk” with the word "hazard” was more common in Slavic, Uralic, Baltic, Italian and Germanic language (

Figure 5). Maltese from the Hamito-Semitic group had a small number of substitutions, Greek from the Hellenic group none.

3.1. Number of Inconsistencies in the Old Version of Regulations No. 2002/178, 2004/852, 2004/853 and 2017/625

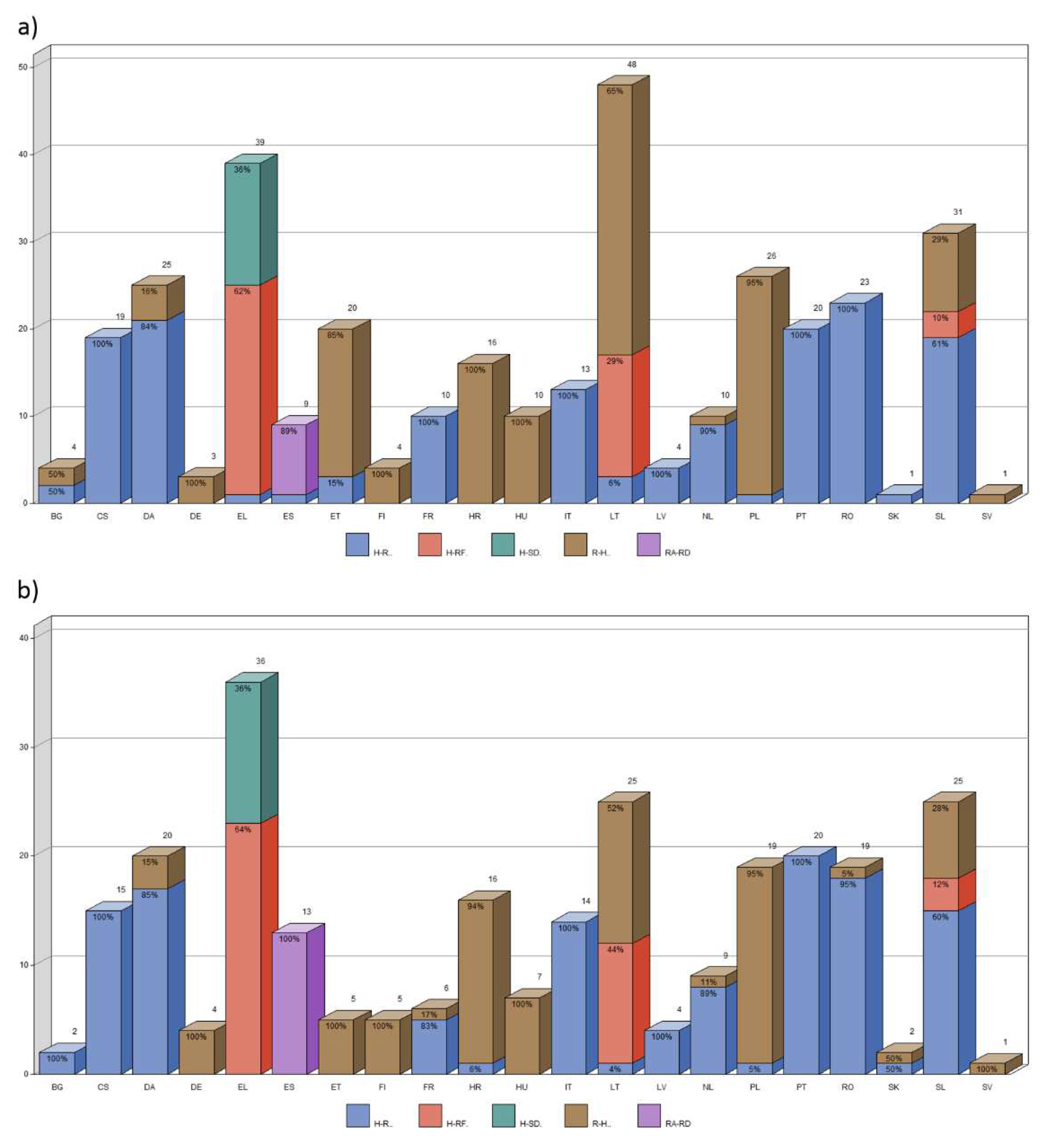

The highest number of inconsistencies identified by consensus between our and the experts’ assessment in the old version of regulations was found for LT (48), EL (39), and for SL (31); for the other, the number of inconsistencies was less than 30 (

Figure 6a). The lowest number was found and confirmed for SV (1) and SK (1).

Figure A1 (a) in Appendix shows the number of inconsistencies in old versions of regulations No. 2002/178, 2004/852, 2004/853 and 2017/625 found by our (author) assessment.

3.2. Number of Inconsistencies in the New Version of Regulations No. 2002/178, 2004/852, 2004/853 and 2017/625

The highest number of inconsistencies identified by consensus between our and the experts’ assessment in the new version of regulations was for EL (36), followed by LT (25) and SL (25); for the others, the number of inconsistencies was less than 25 (

Figure 6b). The lowest number was found and confirmed for SV (1).

The number of expert-confirmed inconsistencies in the new version of Regulations (EU) 2002/178, 2004/852, 2004/853, 2017/625 was 20.5 % lower than in the old version of the same regulations.

Figure A1 (b) in Appendix shows the number of inconsistencies in new versions of regulations No. 2002/178, 2004/852, 2004/853 and 2017/625 found in our assessment.

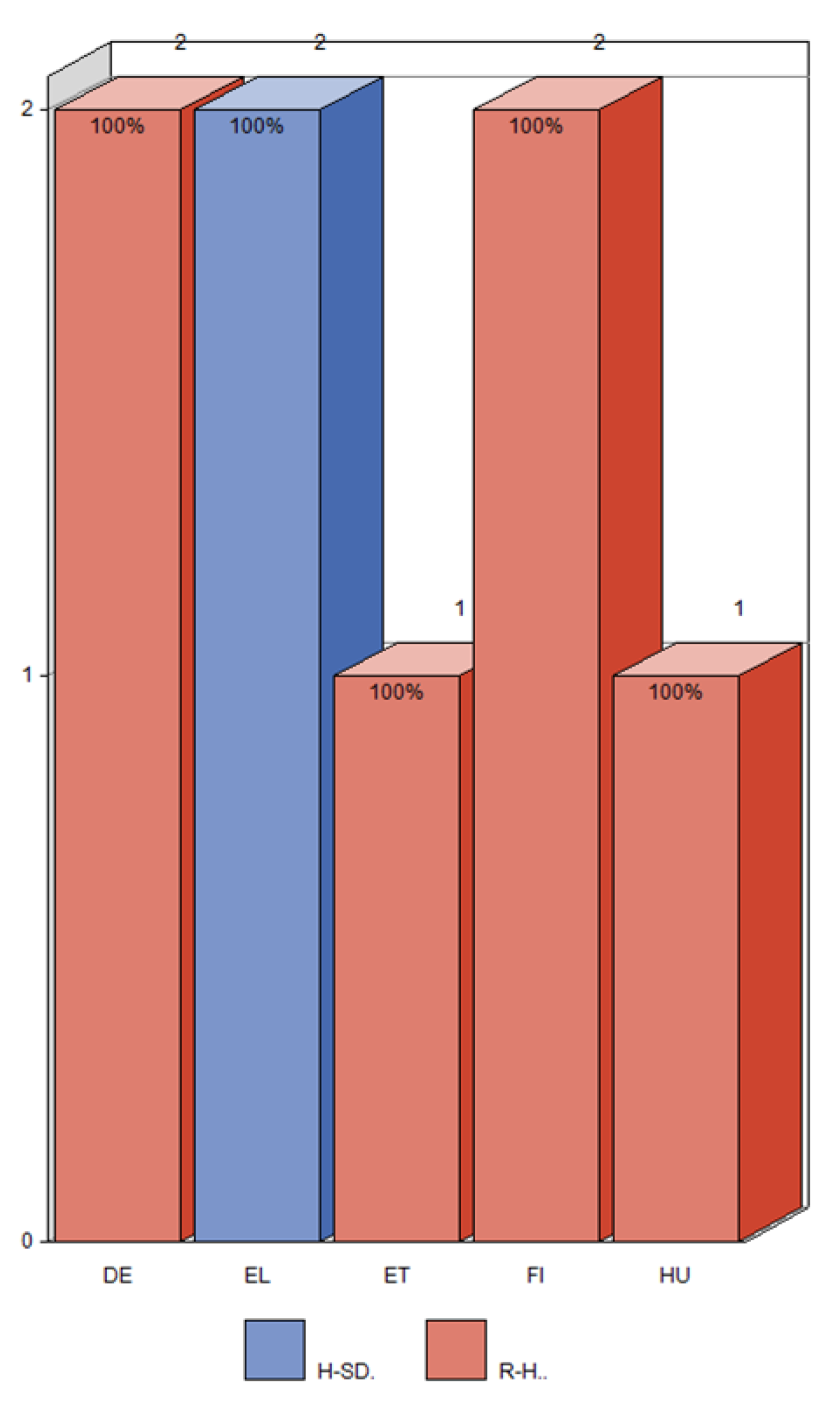

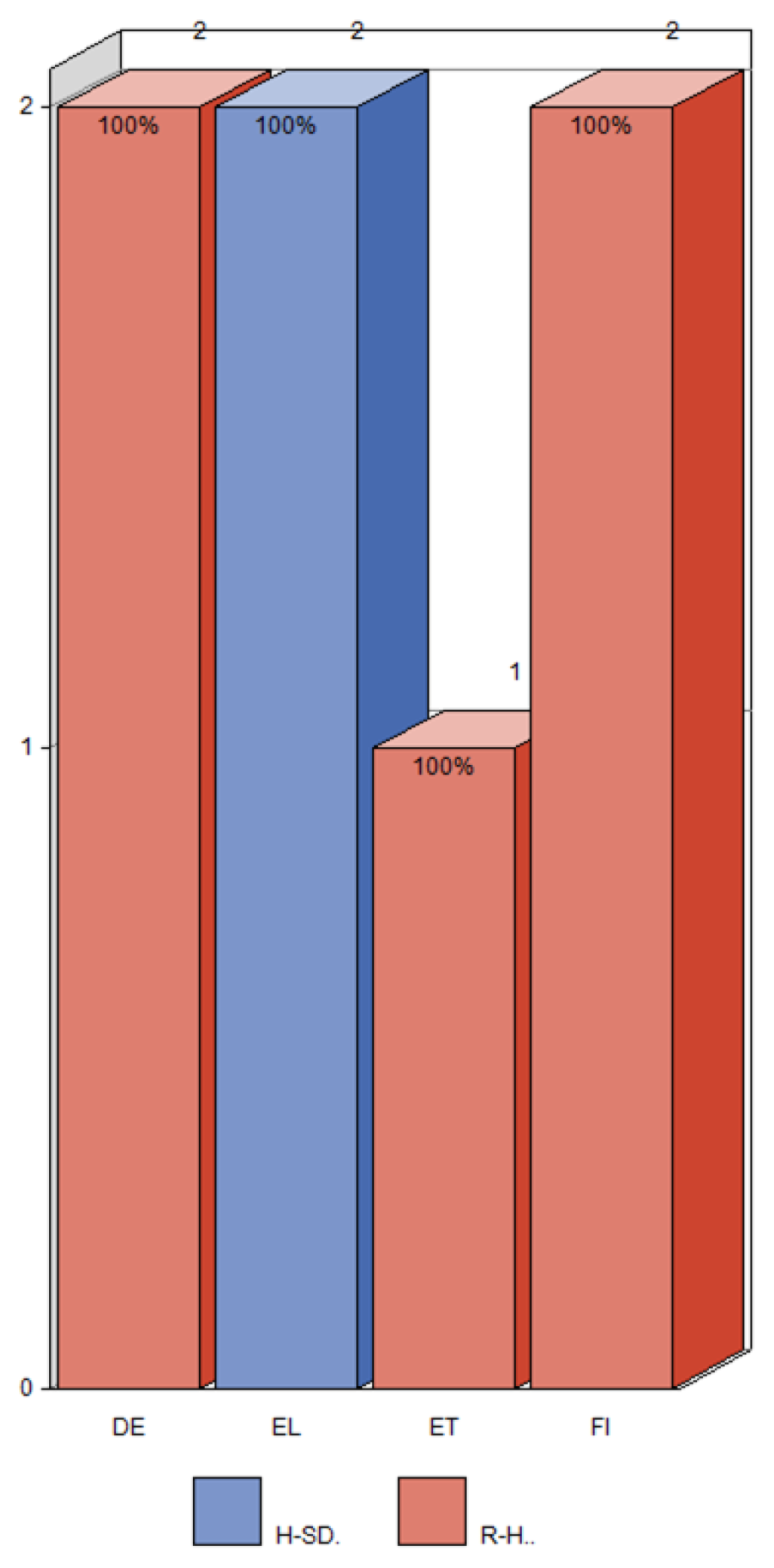

3.3. Number of Inconsistencies in the Single Regulation (EU) No 2019/1381

The Regulation No. 2019/1381 was the newest by the date of publication. Not surprisingly, the number of inconsistencies identified by consensus between our and the experts’ assessment per language was very low (the highest was 2) (

Figure 7) compared to the regulations with old and new versions. In addition, we found one inconsistency in Hungarian. However, the national experts did not agree on this case.

Figure A2 in Appendix shows the number of inconsistencies identified by the authors.

3.4. Correlations between the Variables

In the old/new versions of regulations No. 2002/178, 2004/852, 2004/853 and 2017/625 as well as in the single regulation No. 2019/1381, some relationships among variables, for example, ‘’agreed scores between authors and native food experts’’, ‘’language groups’’, ‘’different languages’’ and ‘’accession years’’, were statistically significant based on the results of Spearman rank correlation coefficients calculations. The Spearman rank correlation coefficients calculations are presented in

Table A1,

Table A2 and

Table A3 in

Appendix A.

In the case of old versions of Regulations No. 2002/178, 2004/852, 2004/853 and 2017/625, the relationships between “different languages” or “language groups” with “evaluators” in general (p=0.0381) and “the year of the state’s accession to the EU” with “groups of languages” or “language groups” (p<0.0001) were the main factors determining the number of inconsistencies found (in this case R-H, H-RF, RA-RD, H-SD, and H-R). In the new versions of these regulations, the same relationships were still open except “groups of languages” with “evaluators”.

In the case of the single Regulation EU No. 2019/1381, no statistically significant correlations were found for the above listed variables.

3.5. Comparisons by Using Kruskal Wallis Test

Comparison of the type of authors/experts agreed inconsistencies between old/new Regulations No. 2002/178, 2004/852, 2004/853 and 2017/625, and Regulation 1381 revealed a statistically significant difference (p=0.03).

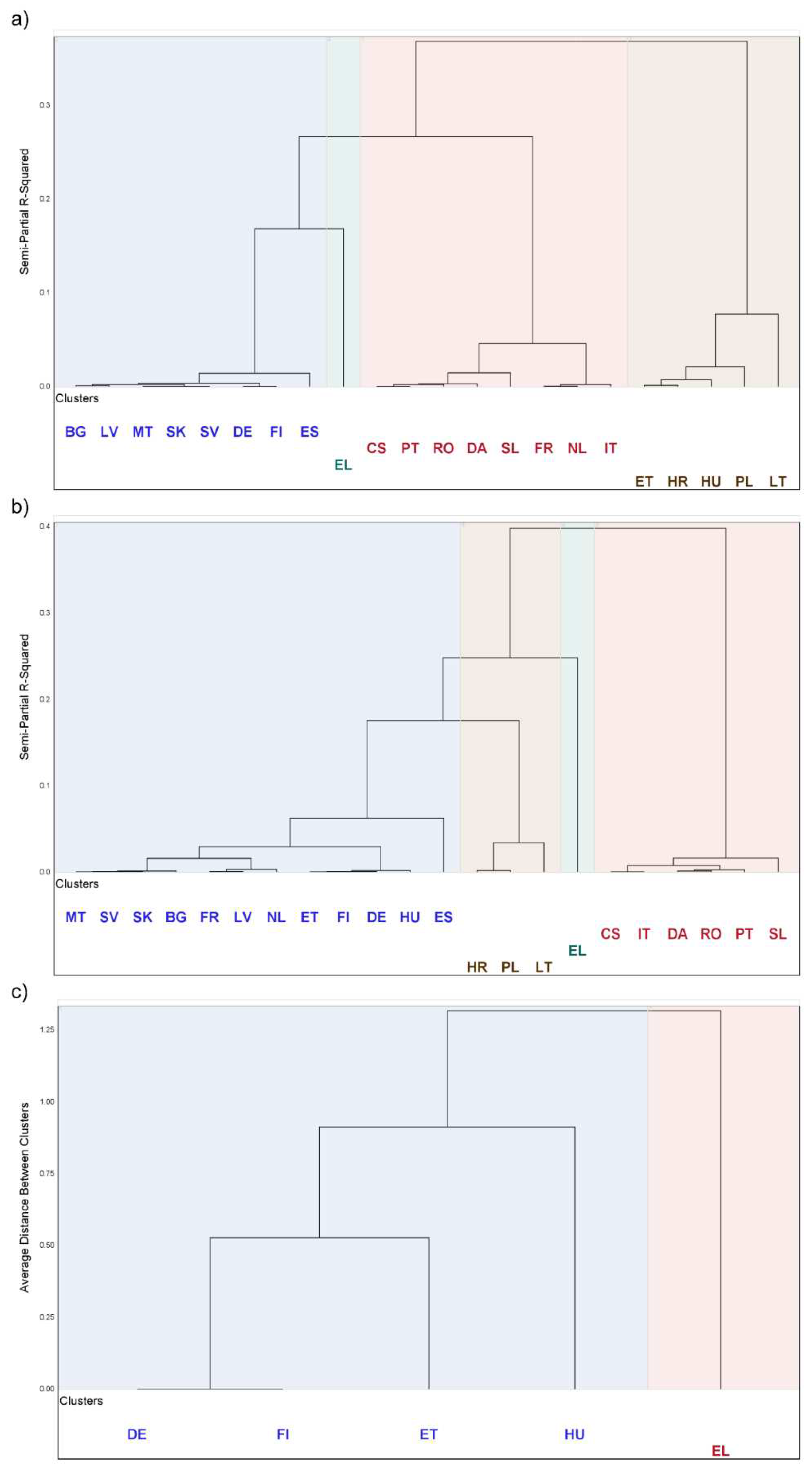

3.6. Clusters

In the old versions of Regulations EU No. 2002/178, 2004/852, 2004/853 and 2017/625, language EL was in the separate cluster (green) due to the highest number of inconsistencies (

Figure 8). The group of languages ET, HU, HR, PL, and LT belonged to the cluster (brown) with a percentage of R-H substitutions above 65% and the total number of inconsistencies between 10 and 48. Languages CS, PT, RO, DA, and SL formed the cluster (red) with a proportion of H-R over 61% and a total number of inconsistencies between 19 and 31. The cluster of language group consisting of FR, NL, and IT (inside the blue) had a proportion of H-R over 90%, but the number of inconsistencies was low – between 10 and 13. The remaining languages of the old versions were also placed in the blue cluster, which had a smaller number of R-H and H-R type of inconsistencies than the second and third cluster (from 1 to 9).

In the new versions of Regulations EU No. 2002/178, 2004/852, 2004/853 and 2017/625, language EL was again in the separate cluster (green) due to the highest number of inconsistencies. The brown cluster of inconsistencies included HR, HU, PL, LT with R-H exceeding 52% and ranging from 16 to 25 inconsistencies. The cluster (red) consisted of CS, IT, DA, RO, PT and SL with H-R percentage over 60% and the total number of inconsistencies ranging from 14 to 25. The blue cluster of languages had two types of inconsistencies R-H or/and H-R and their total number was between 1 and 13.

In the case of single Regulation (EU) No 2019/1381, languages were divided into two clusters, with only EL included in the second cluster.

Figure A3 in the Appendix shows the division into clusters in terms of the number of inconsistencies identified solely by us using the exact translations of risk and hazard. The result was similar to the classification in

Figure 8. The clustering of the different EU members did not result in a particular group of countries, but showed that the same translation problems exist in all countries. However, EL was shown in a separate cluster because only this language had the combination H-SD (35.9%) and H-RF (61.5%) and the proportion did not differ between the new (brown) and the old (blue) regulation (

Figure 8). ES was an exception and was positioned in the blue cluster, but with a separate branch for the old regulation, which only had a proportion of RA-RD (72.7%) and a small proportion of H-R (27.3%). The same is true for ES in the new regulation (RA-RD 92.9%, H-R 7.1%). The low proportion of H-R is the reason why it was positioned in the blue cluster.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, no study has yet been carried out to investigate the inconsistencies in the translation of "hazard" and "risk" in EU food legislation. With the presented analysis of selected EU regulations dealing with food safety, we focus on the inconsistencies in the translations of “hazard” and “risk”, opening the possibility of harmonizing EU regulations even at a higher level. The program HA-RI and the automatic search for inconsistencies, the prepared lists of inconsistencies and their assessment represent efficient tools for the evaluation and harmonisation of the EU legislation.

The number of inconsistencies (the number agreed upon between us and national food experts) decreased significantly when comparing the “old” and “new” regulations, from 336 to 267 (

Table 5). However, some problems remain. Some countries have successfully reduced the number of inconsistencies between old and new legislation (e.g., LT, ET), while others remained the same or nearly the same (e.g., EL, PT) or even increased them (e.g., ES). Problems in translation may arise from insufficient knowledge on the part of the translators, but also from the lack of appropriate terminology in the national languages. It is expected that these problems will be overcome over time. A good example is the latest Regulation 2019/1381, where relatively few inconsistencies in translations were found, indicating that the new terminology has already taken hold.

Overall, Lithuanian (LT) showed a high number of inconsistencies. Most of them were related to the interchangeability of "hazard" with "risk". The same interchange was frequently observed in languages that scored high in the total number of inconsistencies, such as in Slovene (SL), Polish (PL), Danish (DA), Romanian (RO) and Portuguese (PT) (

Table 5,

Figure 4). The same languages with the exception of Lithuanian and Polish revealed inconsistencies related to the interchangeability of “risk” with “hazard”

Table 5,

Figure 5.

Another language that showed an overall high score was Greek. The issues in Greek language (EL) were more related to the fact that “hazard” was carried over either as a “source of danger” (πηγή κινδύνου) in Regulation No. 178/2002, which also contains the section defining the terms, and in Regulation No. 852/2004, or as a “risk factor”, which was so defined and used in Regulation No. 625/2017. In Regulation No. 625/2017, the same term “hazard” is defined differently and used in this form throughout the regulation, although it is the same exact term that was already defined in Regulation No. 178/2002. The new term for “hazard” in this newer 2017 regulation is “risk factor” (‘παράγοντας κινδύνο’). This could lead to a confusion and misunderstanding.

In the case of Spanish, the problem started already with the translation of “risk assessment” in Regulation No. 178/2002. “Risk assessment” is defined as “determinación del riesgo” or “risk determination” instead of the more appropriate expression “evaluacíon de riesgo”. Most food experts involved agreed that the translation does not reflect the intended meaning and is open to interpretation. An accurate translation is available and therefore there is no reason for inconsistencies. In the languages of the Romance family, “hazard” is translated with a word more equivalent to “danger” (e.g., “danger” in French, “peligro” in Spanish, “perigo” in Portuguese, “pericolo” in Italian, “pericol” in Romanian). The countries speaking these languages joined the EU as follows: 1957 - France, Italy, 1986 - Spain, Portugal and 2007 - Romania. There is a difference of 29 years between the accession of France and Italy and the accession of Spain and Portugal. There is another difference of 21 years between the accession of Spain and Portugal and the accession of Romania. A slight increase in translation inconsistencies was noted, with older Romance-speaking member states having fewer inconsistencies than newer members: France and Italy compared to Portuguese and Romanian with Spanish standing out.

The results suggest that inconsistencies in the translation of “hazard” and “risk” exist in all EU countries at the level of food regulations. They may therefore be a potential source of confusion for stakeholders, who should be able to distinguish between the two terms in order to be aware of and actively engage in the food safety issue.

5. Conclusions

In summary, food regulations translated from English into other official EU languages constantly interchange "hazard" and "risk". Furthermore, the results have shown that the translation of food regulations and the subsequent corrections depend on the selected group of experts who undertake this task.

It is strongly recommended that risk managers, with the support of risk assessors, adequately train staff responsible for translating food regulations at national level for each EU Member State. Terminology should be clearly explained and always used as defined. Definitions should be re-evaluated and corrected as necessary. These measures can lead to better harmonisation of food regulations in the EU and thus to a better understanding of food safety. It is also advisable to correct all existing food regulations that contain this type of terminology and ensure the correctness of future documents.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.L. and L.T; methodology, T.L. and L.T; software, L.T.; validation, L.T.; formal analysis, L.T.; investigation, A-A.C.; data curation, A-A.C. and L.T.; writing—original draft preparation, A-A.C. L.T. and T.L..; writing—review and editing, A-A.C., T.L. and L.T.; supervision, T.L. and L.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project was funded by EFSA as part of the European Food Risk Assessment Fellowship Programme (EU-FORA), cohort 2021 – 2022, under agreement GP/EFSA/ENCO/2020/04 -GA1. Scientific evaluations are independent and do not represent the opinion of EFSA.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of EFSA and express their special thanks to the EU-FORA Fellows and representatives of EFSA Focal Points for their contribution to this study. Special thanks also go to Mihai Macrea, senior full stack developer, who helped to create the software tool for identifying inconsistencies-based comparisons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Number of inconsistencies found by the authors, proportion of type of inconsistencies: H-R (blue), H-RF (red), H-SD (green), R-H (brown), and RA-RD (violet) and regarding old (a) and new (b) regulations No. 2002/178, 2004/852, 2004/853 and 2017/625. In case of multiple experts ratings, the average rating of all experts in the respective language group was calculated. The short names of the languages are listed in

Table 5.

Figure A1.

Number of inconsistencies found by the authors, proportion of type of inconsistencies: H-R (blue), H-RF (red), H-SD (green), R-H (brown), and RA-RD (violet) and regarding old (a) and new (b) regulations No. 2002/178, 2004/852, 2004/853 and 2017/625. In case of multiple experts ratings, the average rating of all experts in the respective language group was calculated. The short names of the languages are listed in

Table 5.

Figure A2.

Number of inconsistencies found by the authors, proportion of type of inconsistencies: H-SD (blue) and R-H (red) in Regulation No. 1381. In case of multiple experts ratings, the average rating of all experts in the respective language group was calculated. The abbreviated names of the languages are listed in

Table 5.

Figure A2.

Number of inconsistencies found by the authors, proportion of type of inconsistencies: H-SD (blue) and R-H (red) in Regulation No. 1381. In case of multiple experts ratings, the average rating of all experts in the respective language group was calculated. The abbreviated names of the languages are listed in

Table 5.

Figure A3.

Clustering of languages with respect to the number of R-H, H-RF, RA-RD, H-SD and H-R inconsistencies identified by us (authors) based on exact translations of hazard and risk in a) old Regulations EU No. 2002/178, 2004/852, 2004/853 and 2017/625 (Ward method of clustering), b) new Regulations EU No. 2002/178, 2004/852, 2004/853 and 2017/625 (Ward method of clustering) and c) single Regulation EU No. 1381 (centroid method of clustering). The short names of the languages are listed in

Table 5.

Figure A3.

Clustering of languages with respect to the number of R-H, H-RF, RA-RD, H-SD and H-R inconsistencies identified by us (authors) based on exact translations of hazard and risk in a) old Regulations EU No. 2002/178, 2004/852, 2004/853 and 2017/625 (Ward method of clustering), b) new Regulations EU No. 2002/178, 2004/852, 2004/853 and 2017/625 (Ward method of clustering) and c) single Regulation EU No. 1381 (centroid method of clustering). The short names of the languages are listed in

Table 5.

Table A1.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients calculated for the variables of the OLD versions of Regulations EU No. 2002/178, 2004/852, 2004/853, 2017/625. Accession years are shown in

Table 4. Groups of languages and different languages are shown in

Table 3. Parameters in the rows of each table column are (1) Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients; (2) Prob > |r| under H0: Rho=0; (3) Number of observations. Rank correlation coefficients with p<0.05 are highlighted in red.

Table A1.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients calculated for the variables of the OLD versions of Regulations EU No. 2002/178, 2004/852, 2004/853, 2017/625. Accession years are shown in

Table 4. Groups of languages and different languages are shown in

Table 3. Parameters in the rows of each table column are (1) Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients; (2) Prob > |r| under H0: Rho=0; (3) Number of observations. Rank correlation coefficients with p<0.05 are highlighted in red.

| |

Agreed scores between authors and native food experts |

Groups of Languages |

Years of EU Accession |

Different Languages |

| Agreed scores between authors and native food experts |

1.00000

361 |

-0.04940

0.3493

361 |

-0.05344

0.3113

361 |

0.10923

0.0381

361 |

| Groups of Languages |

-0.04940

0.3493

361 |

1.00000

361 |

0.44076

<.0001

361 |

-0.05212

0.3234

361 |

| Years of EU Accession |

-0.05344

0.3113

361 |

0.44076

<.0001

361 |

1.00000

361 |

0.30134

<.0001

361 |

| Different Languages |

0.10923

0.0381

361 |

-0.05212

0.3234

361 |

0.30134

<.0001

361 |

1.00000

361 |

Table A2.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients calculated for the variables of the NEW versions of Regulations EU No. 2002/178, 2004/852, 2004/853, 2017/625. Accession years are shown in

Table 4. Groups of languages and different languages are shown in

Table 3. Parameters in the rows of each table column are (1) Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficients; (2) Prob > |r| under H0: Rho=0; (3) Number of observations. Rank correlation coefficients with p<0.05 are highlighted in red.

Table A2.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients calculated for the variables of the NEW versions of Regulations EU No. 2002/178, 2004/852, 2004/853, 2017/625. Accession years are shown in

Table 4. Groups of languages and different languages are shown in

Table 3. Parameters in the rows of each table column are (1) Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficients; (2) Prob > |r| under H0: Rho=0; (3) Number of observations. Rank correlation coefficients with p<0.05 are highlighted in red.

| |

Agreed scores between authors and native food experts |

Groups of Languages |

Years of EU Accession |

Different Languages |

| Agreed scores between authors and native food experts |

1.00000

288 |

-0.19834

0.0007

288 |

-0.18237

0.0019

288 |

-0.10139

0.0859

288 |

| Groups of Languages |

-0.19834

0.0007

288 |

1.00000

288 |

0.44684

<.0001

288 |

-0.03616

0.5411

288 |

| Years of EU Accession |

-0.18237

0.0019

288 |

0.44684

<.0001

288 |

1.00000

288 |

0.34442

<.0001

288 |

| Different Languages |

-0.10139

0.0859

288 |

-0.03616

0.5411

288 |

0.34442

<.0001

288 |

1.00000

288 |

Table A3.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients calculated for the variables of the SINGLE regulation EU No. 2019/1381. Accession years are shown in

Table 4. Groups of languages and different languages are listed in

Table 3. Parameters in the rows of each table column are (1) Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficients; (2) Prob > |r| under H0: Rho=0; (3) number of observations.

Table A3.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients calculated for the variables of the SINGLE regulation EU No. 2019/1381. Accession years are shown in

Table 4. Groups of languages and different languages are listed in

Table 3. Parameters in the rows of each table column are (1) Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficients; (2) Prob > |r| under H0: Rho=0; (3) number of observations.

| |

Agreed scores between authors and native food experts |

Groups of Languages |

Years of EU Accession |

Different Languages |

| Agreed scores between authors and native food experts |

1.00000

8 |

0.00000

1.0000

8 |

-0.53452

0.1723

8 |

-0.25198

0.5472

8 |

| Groups of Languages |

0.00000

1.0000

8 |

1.00000

8 |

0.50000

0.2070

8 |

0.47140

0.2383

8 |

| Years of EU Accession |

-0.53452

0.1723

8 |

0.50000

0.2070

8 |

1.00000

8 |

0.47140

0.2383

8 |

| Different Languages |

-0.25198

0.5472

8 |

0.47140

0.2383

8 |

0.47140

0.2383

8 |

1.00000

8 |

References

- WHO, WHO global strategy for food safety 2022–2030: towards stronger food safety systems and global cooperation: executive summary. 2022, Geneva: World Health Organization.

- EFSA, EFSA Strategy 2027 – Science Safe food Sustainability. 2021, Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg.

- FAO, Strategic Framework 2022-31. 2022, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome.

- Crippa, M., et al., Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions. Nature Food, 2021. 2(3): p. 198-209. [CrossRef]

- Fanzo, J., et al., The effect of climate change across food systems: Implications for nutrition outcomes. Global Food Security, 2018. 18: p. 12-19. [CrossRef]

- FAO. The share of food systems in total greenhouse gas emissions. Global, regional and country trends 1990–2019. FAOSTAT Analytical Brief Series No. 31 2021; Available from: https://www.fao.org/3/cb7514en/cb7514en.pdf.

- Tubiello, F., et al., Greenhouse gas emissions from food systems: Building the evidence base. Environmental Research Letters, 2021. 16: p. 65007. [CrossRef]

- Institute., I.F.P.R., 2022 Global Food Policy Report: Climate Change and Food Systems 2022. : Washington, DC.

- Garcia, S.N., B. I. Osburn, and M.T. Jay-Russell, One Health for Food Safety, Food Security, and Sustainable Food Production. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 2020. 4.

- FAO, Safe and sustainable food systems in an era of accelerated climate change, in The FAO/WHO/WTO International Forum on Food Safety and Trade. 2018, FAO: Rome, Italy.

- EFSA, Climate change as a driver of emerging risks for food and feed safety, plant, animal health and nutritional quality. EFSA Supporting Publications, 2020. 17(6): p. 1881E.

- Feliciano, R.J. , et al., Strategies to mitigate food safety risk while minimizing environmental impacts in the era of climate change. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 2022. 126: p. 180-191. [CrossRef]

- Owino, V. , et al., The impact of climate change on food systems, diet quality, nutrition, and health outcomes: A narrative review. Frontiers in Climate, 2022. 4: p. 941842. [CrossRef]

- Devos, Y. , et al., Advancing food safety: strategic recommendations from the ‘ONE – Health, Environment & Society – Conference 2022’. EFSA Journal, 2022. 20(11): p. e201101.

- World Health, O. , Food, and N. Agriculture Organization of the United, Risk communication applied to food safety: handbook. 2016, Rome: World Health Organization.

- Wall, P.G. and J. Chen, Moving from risk communication to food information communication and consumer engagement. npj Science of Food, 2018. 2(1): p. 21. [CrossRef]

- Vaqué, L.G. and I. Segura, Food Risk Communication in the EU and Member States: Effectiveness, Transparency and Safety. European Food and Feed Law Review, 2016. 11(5): p. 388-399.

- Commission, E. , Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 January 2002 laying down the general principles and requirements of food law, establishing the European Food Safety Authority and laying down procedures in matters of food safety. Official Journal Vol. L 31. 2002, Luxembourg: The Publications Office of the European Union. 1–24.

- Young, S.L., J. W. Brelsford, and M.S. Wogalter, Judgments of Hazard, Risk, and Danger: Do They Differ? Proceedings of the Human Factors Society Annual Meeting, 1990. 34(5): p. 503-507.

- Scheer, D. , et al., The Distinction Between Risk and Hazard: Understanding and Use in Stakeholder Communication. Risk Analysis, 2014. 34(7): p. 1270-1285. [CrossRef]

- FAO and WHO. Codex Alimentarius Commission. Procedural Manual. 2015 [cited 2022 4 April 2022]]; Nineteenth edition:[Available from: https://www.fao.org/3/i4354e/i4354e.pdf.

- Wiedemann, P.M. , Schütz, H., Spangenberg, A., Evaluation of Communication on the Differences between “Risk” and “Hazard”, ed. E. Ulbig, Hertel, R. F., Böl, G.-F. 2010, Germany: Federal Institute for Risk Assessmen.

- Freudenstein, F. , et al., Framing effects in risk communication messages – Hazard identification vs. risk assessment. Environmental Research, 2020. 190: p. 109934.

- EFSA. Hazard vs Risk. 2016 [cited 2022 20 April 2022]; Infographic]. Available from: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/images/infographics/hazard-vs-risk-2016.pdf. 20 April.

- EUFIC. Difference Between Hazard and Risk (Infographic). 2017 [cited 2022 20 April 2022]; Infographic]. Available from: https://www.eufic.org/images/uploads/understanding-science/Hazard_Vs_Risk_-_Print_-_en.pdf. 20 April.

- Commission, E. , Regulation (EU) 2017/625 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 March 2017 on official controls and other official activities performed to ensure the application of food and feed law, rules on animal health and welfare, plant health and plant protection products, amending Regulations (EC) No 999/2001, (EC) No 396/2005, (EC) No 1069/2009, (EC) No 1107/2009, (EU) No 1151/2012, (EU) No 652/2014, (EU) 2016/429 and (EU) 2016/2031 of the European Parliament and of the Council, Council Regulations (EC) No 1/2005 and (EC) No 1099/2009 and Council Directives 98/58/EC, 1999/74/EC, 2007/43/EC, 2008/119/EC and 2008/120/EC, and repealing Regulations (EC) No 854/2004 and (EC) No 882/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council, Council Directives 89/608/EEC, 89/662/EEC, 90/425/EEC, 91/496/EEC, 96/23/EC, 96/93/EC and 97/78/EC and Council Decision 92/438/EEC (Official Controls Regulation)Text with EEA relevance. Official Journal. Vol. L 95. 2017, Luxembourg. 1–142. 15 March.

- Attrey, D.P. , Chapter 5 - Role of risk analysis and risk communication in food safety management, in Food Safety in the 21st Century, R.K. Gupta, Dudeja, and M. Singh, Editors. 2017, Academic Press: San Diego. p. 53-68.

- Yavuz-Düzgün, M. , et al., Communicating Food Safety: Ethical Issues in Risk Communication. 2018. p. 157-166. [CrossRef]

- Maxim, L. , et al., Technical assistance in the field of risk communication. Efsa j, 2021. 19(4): p. e06574. [CrossRef]

- Lofstedt, R.E. , Risk versus Hazard – How to Regulate in the 21st Century. European Journal of Risk Regulation, 2011. 2(2): p. 149-168.

- Commission, E. , Regulation (EC) No 852/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on the hygiene of foodstuffs. Official Journal ed. E. Commission. Vol. L 139. 2004, Luxembourg: The Publications Office of the European Union. 1–54. 29 April.

- Commission, E. , Regulation (EC) No 853/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 laying down specific hygiene rules for food of animal origin. Official Journal ed. E. Commission. Vol. L 139. 2004, Luxembourg: The Publications Office of the European Union 55–205. 29 April.

- Commission, E. , Regulation (EU) 2019/1381 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on the transparency and sustainability of the EU risk assessment in the food chain and amending Regulations (EC) No 178/2002, (EC) No 1829/2003, (EC) No 1831/2003, (EC) No 2065/2003, (EC) No 1935/2004, (EC) No 1331/2008, (EC) No 1107/2009, (EU) 2015/2283 and Directive 2001/18/EC (Text with EEA relevance.). Official Journal, ed. E. Commission. Vol. L 231. 2019, Luxembourg. 1–8. 20 June.

- EUR-lex. Access to the European Union Law. 2021 [cited 2022 15 January]; Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/collection/eu-law/legislation/recent.html.

- Inc., S.I. Inc., S.I., SAS Technical Report A-108 Cubic Clustering Criterion. 1983: Cary, NC, USA. p. 56.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).