1. Introduction

The information gathered over the past two decades regarding the impact of menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) holds promise for a more reliable and successful long-term approach to managing menopause symptoms and potential complications. These complications may encompass osteoporotic fractures, cognitive impairment, cardiovascular conditions, and an overall enhanced quality of life1-4. With these findings in mind, international organizations have determined that the benefits of MHT outweigh the associated risks for healthy postmenopausal women experiencing symptoms, particularly if the therapy commences within a decade of menopause or before the age of 605,6.

Nevertheless, there is currently a lack of guidelines that offer recommendations on prescribing MHT to postmenopausal women who have medical conditions that could affect its use. In the realm of contraception, a comprehensive resource known as the "WHO Medical Eligibility Criteria" provides guidance on various medical conditions, aiding the scientific community in ensuring the safe use of contraceptive methods7.

Among the factors that significantly influence the suitability of any form of MHT is a history of non-gynecological cancers such as colorectal, lung, or melanoma. The concern lies in the potential recurrence of these diseases since there are evidences of a potential sensitivity to estrogens as clarified below Moreover, a considerable number of women who have survived these cancers have undergone treatments that intensify menopausal symptoms due to the effects of cancer therapies. This further underscores the importance of providing effective remedies for these individuals, with MHT being one of the noteworthy options8

In previous articles, we have addressed the impact of menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) on the evolution of gynecological cancer. However, we believe it is important to investigate this issue in other cancers that may be of interest due to their high prevalence and potential relationship with estrogens.

According to the Globocan 2022 study, colon cancer was the second most common cancer in women, with an incidence rate of 16.2 per 100,000 women 9. The WHI study demonstrated a significantly lower incidence of colon cancer following MHT (HR 0.6, CI 0.43-0.92) 10. However, the mechanism by which this reduction occurs remains unclear. It is currently known that estrogen action is mediated by two types of receptors, ERα and ERβ, which interact similarly. ERα interacts more frequently with c-Jun, c-Fos of the activator protein-1 (AP-1) complex, and specificity protein 1 (SP1) 11. On the other hand, ERβ has been shown to have a suppressive effect on tumor progression in certain cancers and has demonstrated therapeutic potential in the management of these malignancies 12. In the normal colon, ERβ plays a crucial role in maintaining physiology and immune response 13. It has been described that estrogen stimulation of these receptors, even with flavonoids 14, can stimulate the tumor suppressor function in colon cancer, thus promoting a protective effect 15.

Lung cancer is the third most common cancer in women, with an incidence of 14.6 per 100,000 women 9. While the relationship between lung cancer and tobacco use is well-established, some studies have also associated endogenous estrogen stimulation or hormonal treatments with the development of this neoplasia. This may be attributed to women's greater susceptibility to tobacco carcinogenesis, primarily due to the induction of the CYP1B1 enzyme, which interferes with estrogen metabolism and leads to increased formation of reactive oxygen species with oncogenic properties 17. The Women's Health Initiative trial concluded that estrogen and progesterone treatment in postmenopausal women did not increase the incidence of lung cancer 10. However, other investigators have demonstrated in vitro that estrogen induces the spread of lung cancer cells in non-small cell tumors, promoting tumor growth 18. Conversely, anti-estrogen treatment strategies have shown potential in decreasing tumor size, cell growth, and proliferation 19.

While gender differences have been observed in the incidence of melanoma, the role of estrogenicity in this divergence remains uncertain. Molecular studies have described a greater presence of ERβ in the skin, inhibiting DNA transcription and significantly reducing tumor capacity, unlike the breast where ERα predominates20. Epidemiologically, the effects of hormonal treatment in women with melanoma have yielded initially divergent results. While some previous studies do not contraindicate hormonal contraception in this tumor 21,22, other authors have shown a higher risk associated with estrogen treatment in postmenopausal women, which is not observed when combined estrogen-progestogen therapy is administered 23.

Based on these biological and clinical considerations, we have selected colon, lung, and melanoma cancers as the focus of our review.

The objective of this report is to create a set of eligibility criteria for the use of MHT in non-gynecological (colorectal, lung or melanoma) cancer patients, similar to those established for contraceptive methods. A panel of experts from various Spanish scientific societies (Spanish Menopause Society, Sociedad Española de Ginecología y Obstetricia and Sociedad Española de Oncología Médica) met in order to draw up a series of evidence-based recommendations.

2. Methods

The study was registered with www.prospero.org under registration number CRD42020166658 and is part of the "Eligibility Criteria for MHT Project" (Appendix 1).

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

The systematic review included randomized controlled trials, extension studies, or follow-up reports. Additionally, observational studies were included, with a special focus on population-based cohorts or large case-control studies that included a control group of non-users. Eligible studies involved menopausal women of any age who received MHT and were survivors of melanoma, colorectal cancer, or lung cancer. We considered studies that evaluated any MHT preparation (including estrogens alone or combined with a progestogen, tibolone, or tissue-selective estrogen complex) administered via any route (oral, transdermal, vaginal, or intra-nasal). The impact of MHT was compared to placebo or non-treatment controls.

2.2. Study Selection

We conducted a comprehensive literature search in the following databases: MEDLINE (via PubMed), The Cochrane Library (CENTRAL), and EMBASE (via embase.com), from their inception to the most recent available date. We developed a search strategy tailored to the requirements of each database, combining controlled vocabulary and search terms related to each specific cancer. Appendix 2 presents an exploratory search strategy for MEDLINE. Validated filters were employed when necessary to retrieve appropriate study designs. Two independent researchers screened the references retrieved from the search to reach a consensus on study inclusion. In case of discrepancies, a member of the expert panel was consulted to resolve them. The panel members were kept informed of this process to assess the suitability of included studies and suggest additional relevant studies if any were omitted. The study scope, along with the procedures, selection, and synthesis of the literature search, adhered to the a priori PICOS (Population, Intervention, Comparators, Outcomes, Study Design) criteria. The selection criteria were as follows:

Population: Menopausal women of any age with non-gynecological and non-breast cancer receiving MHT.

Intervention: Any MHT preparation (including estrogens alone or combined with a progestogen, tibolone, or tissue-selective estrogen complex) administered via any route (oral, transdermal, vaginal, or intra-nasal).

Outcome: Recurrence and mortality.

Study Design: Randomized controlled trials, extension studies, or follow-up reports. Any complete article meeting the inclusion criteria underwent a detailed review.

2.3. Data Extraction, Synthesis, and Risk of Bias Assessment

The panel, consisting of the study authors, reviewed the scientific literature following a predefined protocol based on methodological guidelines from the Cochrane collaboration 24. The findings were reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement 25. For observational studies, the ROBINS-I tool was adapted to assess confounding variables, selection bias, outcome measures, and attrition26. The evidence synthesis followed the PRISMA guidelines, with a narrative synthesis of findings and effect estimates from the included studies focusing on the relevant outcomes to explore the association between MHT and cancer survivors. When appropriate, pooled analyses were conducted using the Mantel-Haenszel method and the random effects model within the RevMan software statistical package (v 5.3.5) 27. Certainty of evidence for each outcome of interest was explicitly assessed using GRADE criteria 28. Quality was classified as high (A), moderate (B), low (C), or very low (D), taking into account factors such as risk of bias, inaccuracy, inconsistency, lack of directionality, and publication bias. In systematic reviews where no direct evidence was identified, but plausibility existed based on clinical experience or publications with indirect evidence, the panel reached consensus and categorized the evidence as "Expert opinion."

2.4. Evidence-to-Decision Framework and Eligibility Criteria

To formulate explicit and reasoned recommendations, we employed an evidence-to-decision (EtD) framework to inform the panel about the most relevant aspects required for decision-making, facilitating justifications29. To establish a ranking of MHT eligibility criteria, the panel integrated findings from the reviews using a structured framework that considered the magnitude of MHT effects on recurrence and mortality, certainty ratings of the evidence, and data from other sources. To standardize the proposal, the following eligibility criteria have been defined in accordance with the WHO international nomenclature:

Category 1: No restriction on the use of MHT

Category 2: The benefits outweigh the risks.

Category 3: The risks generally outweigh the benefits.

Category 4: MHT Should not be used

3. Results

Colorectal cancer

Five observational studies on the use of MHT in women with colorectal cancer (CRC) were identified: two prospective

30,31 and three retrospective

32-34 cohorts totaling 5510 women receiving some form of MHT (

Table 1).

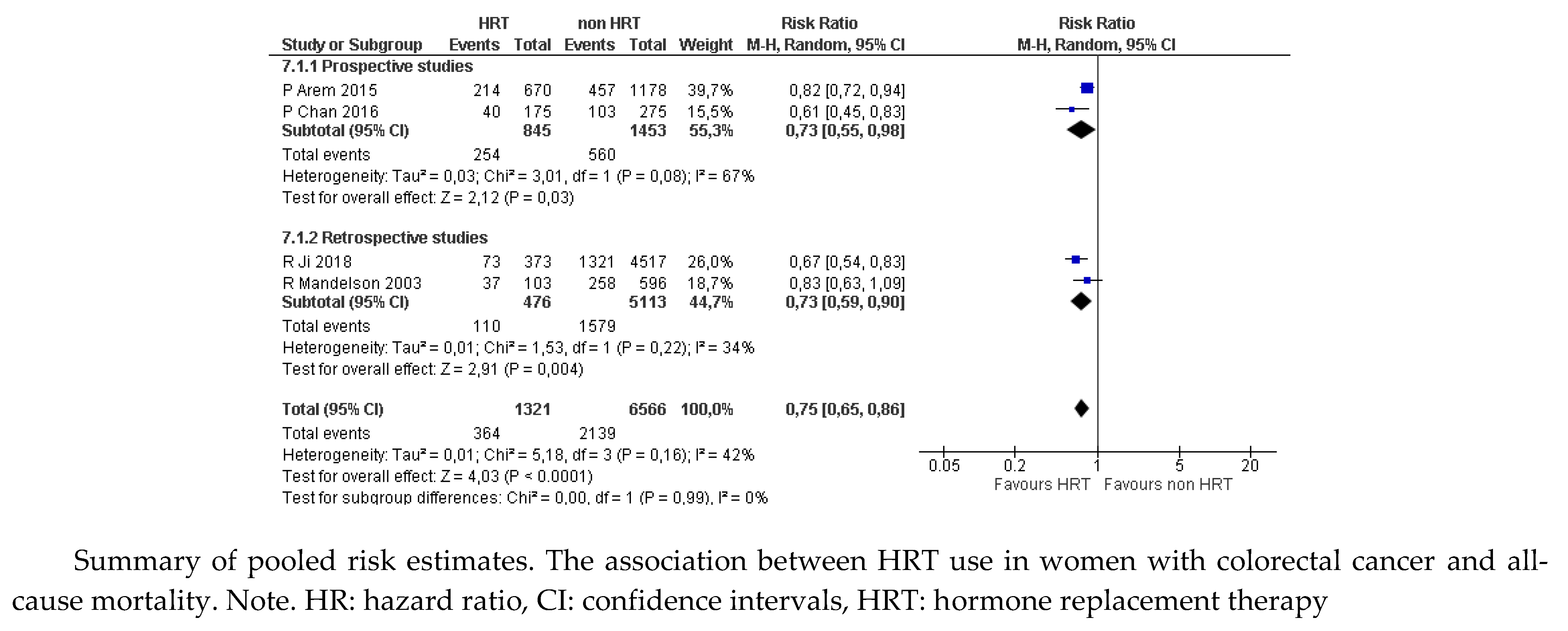

For this report, a combined evaluation was made of the results of four of these studies

30-33 which showed a significant reduction in the proportion of women who died of any cause among those who received MHT compared with those who were untreated (RR 0.75, 95% CI: 0.65 to 0.86;

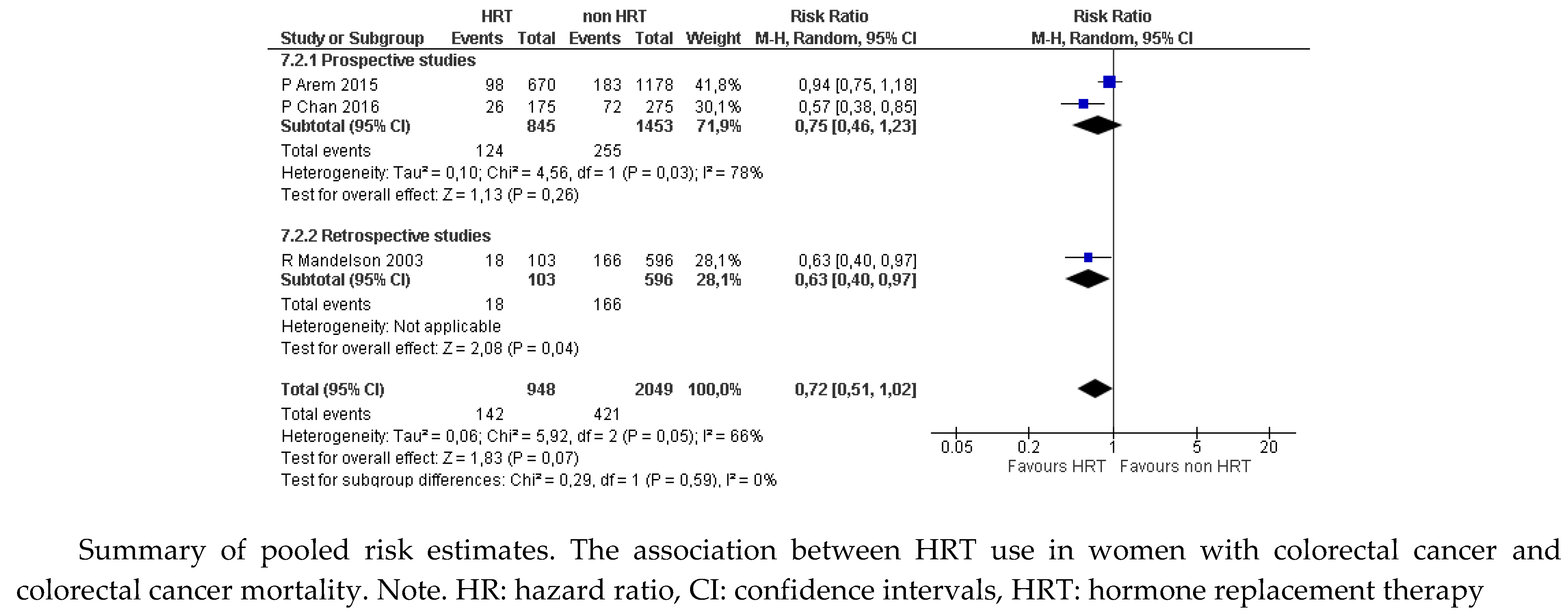

Figure 1a). The results were not statistically significant for the proportion of women with a cause of death attributable to CRC (RR 0.72, 95% CI: 0.52 to 1.02;

Figure 1b), because of the discrepancy between estimates from prospective (RR 0.75, 95% CI: 0.46 to 1.23) and retrospective studies (RR 0.63, 95% CI: 0.40 to 0.97).

Figure 1.

a. Colorectal cancer. Mortality from any cause (data from prospective and retrospective studies).

Figure 1.

a. Colorectal cancer. Mortality from any cause (data from prospective and retrospective studies).

Figure 1.

b. Colorectal cancer. Mortality attributable to colorectal cancer (data from prospective and retrospective studies).

Figure 1.

b. Colorectal cancer. Mortality attributable to colorectal cancer (data from prospective and retrospective studies).

Lung Cancer

Five studies were included on the effect of MHT on lung cancer, three retrospective

35-38 and one prospective

39 collected in a meta-analysis

40 with a total of 1054 women with lung cancer who used MHT compared with 1528 who did not (

Table 2).

No publication bias was observed among these studies. The sensitivity analysis result showed that the overall results were stable. The meta-analysis revealed that in comparison with patients not treated with hormone replacement therapy, patients that received hormone replacement therapy had an increased survival of 5 years (RR=0.346; 95% CI: 0.216 to 0.476; p<0.001).

Cutaneous Melanoma

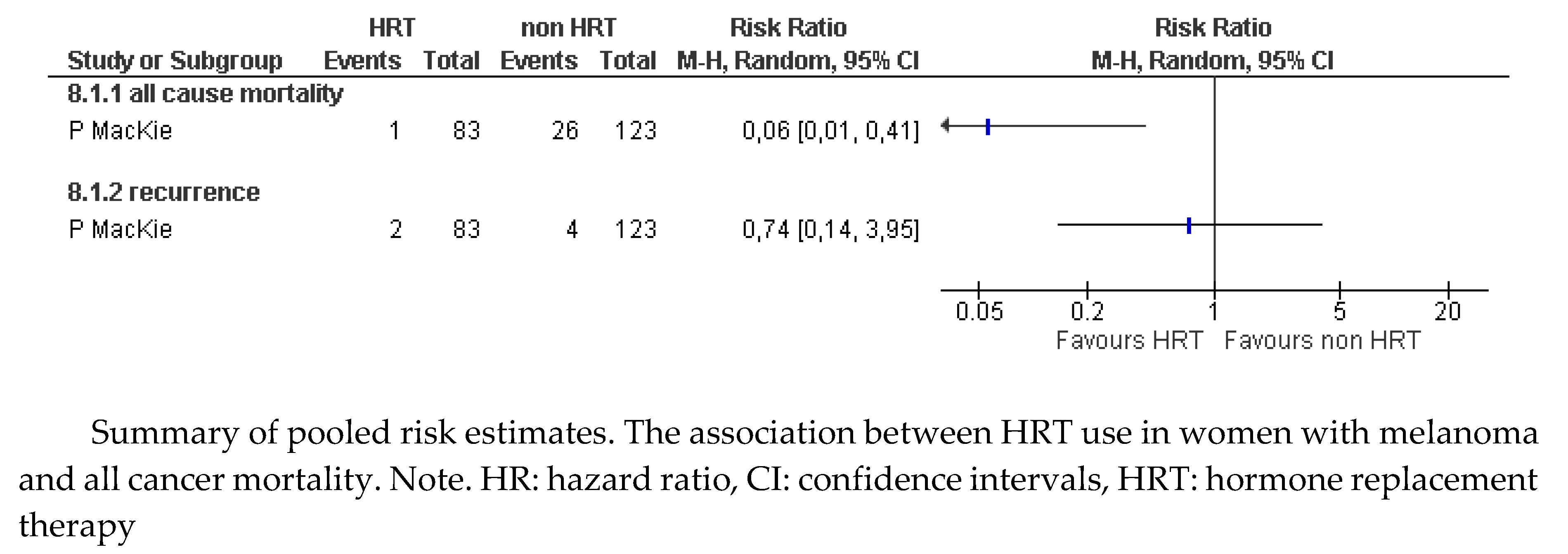

A prospective

41 cohort study was identified that analyzed the effect of MHT in 206 women with cutaneous melanoma (

Table 3). After 10 years of follow-up, adjusted analysis of the results showed increased survival among women who received MHT after melanoma surgery (HR 0.17, 95% CI: 0.04 to 0.62). An estimate of the data provided by the study showed a statistically significant reduction in the risk of death in those who received MHT (RR 0.06, 95% CI: 0.01 to 0.41;

Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Melanoma. Mortality (from any cause) and recurrence.

Figure 2.

Melanoma. Mortality (from any cause) and recurrence.

Regarding recurrences, this study showed no difference in the proportion of women with MHT who suffered recurrences (RR 0.74, 95% CI: 0.14 to 3.95;

Figure 2). The quality of evidence for this outcome is very low due to the serious methodological limitations of the study and the inaccuracy of the estimate attributable to a small sample size.

4. Discussion

On the basis of a combined analysis of the researched literature, it is concluded that MHT is safe, in terms of recurrence and/or mortality, in patients who have suffered some of the most frequent non-gynecological cancers (colorectal, lung or melanoma).

Why is This Report Important?

There is considerable confusion regarding the appropriateness of MHT in women with cancer, primarily because of the fear of recurrence or increased mortality that may occur with its use.

Women who have suffered from cancer often present earlier and more intense menopausal symptoms, due to the effects of some of their treatments, which seriously affect their quality of life. On many occasions, the long-term risks overlap with those suffered by women with premature ovarian insufficiency, thus extending the suitability of MHT8.

Strengths

This is the first published work to present a systematic review and meta-analysis to analyze the recurrence and mortality of MHT in women survivors of the most common non-gynecological cancers (colorectal, lung, and melanoma).

It is also the first time that categories of evidence (eligibility criteria) have been distinguished for the use of MHT in these patients, using the strictest methodological tools.

Limitations

The quality of evidence is low overall. Many studies include the generic use of MHT without distinguishing between dose, formulation, or route of administration.

Clinical Evidence

The recommendation is based on analyzing five observational studies (two prospective cohorts30,31; and three retrospective studies32,34. There are no randomized studies, although the population studied is large, mainly due to the high prevalence of this tumor.

The results point to an increased survival rate, although differences in the means do not reach statistical significance.

This risk reduction is evident during treatment but not after the end of treatment. Better outcomes appear to be associated with estrogens alone than with combined treatments.

There are many limitations, including lack of randomized studies, case collection, BMI, lack of knowledge of the socio-economic profile, and treatment variability.

Results regarding disease-free survival are not sufficiently consistent for drawing conclusions.

The recommendation is based on analyzing five observational studies (three retrospective studies35-38 and one prospective39 pooled in a meta-analysis40

Although most of the results point to reduced survival in female MHT users, particularly smokers, other retrospective studies show better survival in MHT users, especially in female smokers.

The limitations include the absence of randomized studies, different dosages, low prevalence of the disease, and a low number of cases, along with a lack of knowledge of the socio-economic profile.

There are no available data on recurrence rates.

- 2.

Cutaneous melanoma

The recommendation is based on a single cohort study41 with a small sample of women (n=206) but a long follow-up (10 years on average).

There is evidence of longer overall survival in this single study with no differences in disease-free survival. In addition, no differences were found in the various histological types or the depth of the lesion. However, there were differences in tumor ulceration.

The main limitations are the absence of randomized studies, only one follow-up study, and the small sample size. There are no studies to either support or counter these data. Better evolution of the disease in younger women remains to be clarified.

Cancer Risk in Healthy MHT Users

Colorectal Cancer

The results of the WHI study show that the use of equine conjugated estrogens both alone and in combination with medroxyprogesterone was associated with a lower risk of colon cancer10. Further studies have confirmed these results with reductions in the risk of cancer (RR 0.81, p = 0.005) and the risk of death from this cancer (RR 0.63, p = 0.002)42. An 18-year follow-up of women in the WHI study has shown no difference in mortality between treated and untreated women43.

Lung Cancer

Most of the studies aimed at assessing the risk of lung cancer in MHT users have reported positive results in reducing the risk of this type of cancer. Age, smoking, comorbidities and family history have been considered as risk factors in these comparisons, reporting a significant reduction among users compared with non-users (RR 0.80; 95% CI: 0.70-0.93; p=0.009) although no significant differences in mortality rates were found44. Another recent meta-analysis of 13 studies has also shown a reduced risk in users of MHT (RR: 0.95, 95% CI: 0.91-0.99, I = 30.8%, p=0.137)45. And whilst co-factor variability is a major limitation in this assessment, the evidence suggests a protective effect of MHT on the incidence of lung cancer.

Melanoma

After reviewing the literature, the use of MHT has been associated with a significantly increased risk of melanoma (RR, 1.28; 95% CI: 1.17-1.41)46, for both estrogens alone (RR 1.37; 95% CI: 1.22-1.52) and estrogen-progestogen combinations (RR 1.23, 95% CI: 1.13-1.34; P = 0.15) after five years of use47. These same authors reported significant increases in risk of melanoma for both oral and vaginal estrogens, while no such relationship was found with estroprogestagen combination therapy (RR 0.91; 95% CI: 0.70-1.19)23. No differences were found when assessing estrogen doses, sun exposure, or age.

Future Research

Our report has, however, identified some important areas for improvement in future research. We expect that the results will contribute to the development of studies that further examine the safety and efficacy of MHT for treating menopausal symptoms in non-gynecological and breast cancer survivors. Larger RCTs should be conducted over a longer follow-up period to evaluate the various MHT strategies.

5. Conclusions

Female colorectal cancer survivors who use MHT have a lower risk of mortality from any cause than survivors who are non-users: Category 1C.

Female cutaneous melanoma survivors who use MHT have longer survival than non-users: Category 2C.

There is no evidence that female lung cancer survivors who use MHT have a different likelihood of survival than non-users: Category 2C.

DECLARATION SECTION

Author´s contributions

I Lete, G Fiol, Nieto L, N Mendoza l: conception and design of the idea. G Fiol, L Nieto, I Lete, N Mendoza preparation of manuscript. All authors participated in data interpretation, statement and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This article has been translated and edited by Your English Lab. Biomedical Research Institute Sant Pau and CIBERESP (Cochrane Spain) have participated in the methodology of the article.

Conflicts of Interest

There was no funding source and no editorial assistance for this position statement.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

AEEM is responsible for the investigation. It is a systematic review, so it has not required an ethics committee review.

Consent for publication

Spanish Menopause Society, Spanish Society of Medical Oncology and Gynecological Oncology Section of the Spanish Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics are directly involved and responsible of the content of this manuscript: All authors have reviewed and participated in the final writing.

References

- de Villiers TJ, Hall JE, Pinkerton JV, Pérez SC, Rees M, Yang C, Pierroz DD. Revised global consensus statement on menopausal hormone therapy. Maturitas 2016, 91, 153–5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davey, DA. Menopausal hormone therapy: a better and safer future. Climacteric 2018, 21, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chester RC, Kling JM, Manson JE. What the Women's Health Initiative has taught us about menopausal hormone therapy? Clin Cardiol 2018, 41, 247–252. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stepan JJ, Hruskova H, Kverka M. Update on Menopausal Hormone Therapy for Fracture Prevention. Curr Osteoporos Rep 2019;17(6):465-473. [CrossRef]

- Baber RJ, Panay N, Fenton A; IMS Writing Group. 2016 IMS Recommendations on women's midlife health and menopause hormone therapy. Climacteric 2016, 19, 109–50. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2018, 25, 1362–1387. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use: A WHO Family Planning Cornerstone. 4th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [PubMed]

- Mendoza N, Juliá MD, Galliano D, Coronado P, Díaz B, Fontes J, Gallo JL, García A, Guinot M, Munnamy M, Roca B, Sosa M, Tomás J, Llaneza P, Sánchez-Borrego R. Spanish consensus on premature menopause. Maturitas 2015, 80, 220–5. [CrossRef]

- Globocan 2020- Global cancer Observatory. http://gco.iarc.fr/- International agency for Research on Cancer 2023. (Revised June,4th,2023).

- Rossouw J.J., Anderson G.G., Prentice R.R., LaCroix A.A., Kooperberg C., Stefanick M.M., Jackson R.D., Beresford S.A., Howard B.V., Johnson K.C., et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: Principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002, 288, 321–333.

- Matthews J, Wihl.n B, Tujague M, Wan J, Str.m A, Gustafsson JA. Estrogen receptor (ER) beta modulates ERalpha-mediated transcriptional activation by altering the recruitment of c-Fos and c-Jun to estrogen-responsive promoters. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20(3):534-543. [CrossRef]

- Rudolph A, Toth C, Hoffmeister M, et al. Expression of oestrogen receptor β and prognosis of colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2012;107(5):831-839. [CrossRef]

- Looijer-van Langen M, Hotte N, Dieleman LA, Albert E, Mulder C, Madsen KL. Estrogen receptor-β signaling modulates epithelial barrier function. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;300(4):G621-G626. [CrossRef]

- Schleipen B, Hertrampf T, Fritzemeier KH, et al. ERβ-specific agonists and genistein inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis in the large and small intestine. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32(11):1675-1683. [CrossRef]

- Das PK, Saha J, Pillai S, Lam AKY, Gopalan V, Islam F. Implications of estrogen and its receptors in colorectal carcinoma. Cancer Medicine. 2023;12:4367–4379. [CrossRef]

- Peng J, Meireles SI, Xu X, Smith WE, Slifker MJ, Riel SL, Zhai S, Zhang G, Ma X, Kurzer MS, Ma GX, Clapper ML. Estrogen metabolism in the human lung: impact of tumorigenesis, smoke, sex and race/ethnicity. Oncotarget 2017;8:106778–89. [CrossRef]

- Fuentes N, Rodriguez MS, Silveyra P. Role of sex hormones in lung cancer. Experimental Biology and Medicine 2021, 246, 2098–2110. 2021; 246, 2098–2110. [CrossRef]

- Stabile LP, Davis AL, Gubish CT, Hopkins TM, Luketich JD, Christie N, Finkelstein S, Siegfried JM. Human non-small cell lung tumors and cells derived from normal lung express both estrogen receptor alpha and beta and show biological responses to estrogen. Cancer Res 2002;62:2141–50.

- Burns TF, Stabile LP. Targeting the estrogen pathway for the treatment and prevention of lung cancer. Lung Cancer Manag 2014;3:43–52. [CrossRef]

- Dika E, Patrizi A, lambertini M, Manuelpillai N, Fiorentino M, Altimari A, Ferracin M, Lauriola M, Fabbri E, Campione E, Veronesi G, Scarfi F. Estrogen Receptors and Melanoma: A Review. Cells. 2019; 8, 1463. [CrossRef]

- Hannaford, P.; Villard-Mackintosh, L.; Vessey, M.; Kay, C. Oral contraceptives and malignant melanoma. Br. J. Cancer. 1991; 63, 430–433. [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J.R.; Rosenberg, L.; Strom, B.L.; Harlap, S.; Zauber, A.G.; Warshauer, M.E.; Shapiro, S. Oral contraceptive use and risk of cutaneous malignant melanoma. Cancer Causes Control. 1992; 3, 547–554. [CrossRef]

- Botteri E, Støer NC, Sakshaug S, Graff-Iversen S, Vangen S, Hofvind S, Ursin G, Weiderpass E. Menopausal hormone therapy and risk of melanoma: Do estrogens and progestins have a different role? Int. J. Cancer 2017. 141, 1763–1770. 2017. 141, 1763–1770.

- Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2nd Edition. Chichester (UK): John Wiley & Sons, 2019.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. pmed.1000097 PMID: 19621072. [CrossRef]

- Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, Henry D, Altman DG, Ansari MT, Boutron I, Carpenter JR, Chan AW, Churchill R, Deeks JJ, Hróbjartsson A, Kirkham J, Jüni P, Loke YK, Pigott TD, Ramsay CR, Regidor D, Rothstein HR, Sandhu L, Santaguida PL, Schünemann HJ, Shea B, Shrier I, Tugwell P, Turner L, Valentine JC, Waddington H, Waters E, Wells GA, Whiting PF, Higgins JP. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016, 355, i4919.

- Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.4, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2020.

- Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyyat G, Oxman A. Handbook for grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations using the GRADE approach. Updated October 2013. Available from https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/handbook/handbook.html. 20 October.

- Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello- Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to 12 www.eurosurveillance.org making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016;353:i2016. [CrossRef]

- Chan JA, Meyerhardt JA, Chan AT, Giovannucci EL, Colditz GA, Fuchs CS. Hormone replacement therapy and survival after colorectal cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol 2006, 24, 5680–6. [CrossRef]

- Arem H, Park Y, Felix AS, Zervoudakis A, Brinton LA, Matthews CE, Gunter MJ. Reproductive and hormonal factors and mortality among women with colorectal cancer in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Br J Cancer 2015, 113, 562–8. [CrossRef]

- Mandelson MT, Miglioretti D, Newcomb PA, Harrison R, Potter JD. Hormone replacement therapy in relation to survival in women diagnosed with colon cancer. Cancer Causes Control 2003;14(10):979-84. [CrossRef]

- Ji J, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Use of hormone replacement therapy improves the prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer: A population-based study in Sweden. Int J Cancer 2018;142(10):2003-2010. [CrossRef]

- Slattery ML, Anderson K, Samowitz W, Edwards SL, Curtin K, Caan B, Potter JD. Hormone replacement therapy and improved survival among postmenopausal women diagnosed with colon cancer (USA). Cancer Causes Control 1999, 10, 467–73. [CrossRef]

- Ganti AK, Sahmoun AE, Panwalkar AW, et al. Hormone replacement therapy is associated with decreased survival in women with lung cancer[J]. J Clin Oncol 2006, 24(1): 59-63.

- Ayeni O, Robinson A. Hormone replacement therapy and outcomes for women with non-small-cell lung cancer: can an association be confirmed? Curr Oncol 2009;16(3):21-5.

- Katcoff H, Wenzlaff AS, Schwartz AG. Survival in women with NSCLC: the role of reproductive history and hormone use. J Thorac Oncol 2014, 9(3): 355-361. [CrossRef]

- Huang B, Carloss H, Wyatt SW, et al. Hormone replacement therapy and survival in lung cancer in postmenopausal women in a rural population. Cancer 2009, 115(18): 4167-4175. [CrossRef]

- Clague J, Reynolds P, Henderson KD, Sullivan-Halley J, Ma H, Lacey JV Jr, Chang S, Delclos GL, Du XL, Forman MR, Bernstein L. Menopausal hormone therapy and lung cancer-specific mortality following diagnosis: the California Teachers Study. PLoS One 2014, 9, e103735. [CrossRef]

- Li K, Chen L, Huang Y, Luan X. Meta-analysis for the effect of hormone replacement therapy on survival rate in female with lung cancer. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2020;45(4):372-377. [CrossRef]

- MacKie RM, Bray CA. Hormone replacement therapy after surgery for stage 1 or 2 cutaneous melanoma. Br J Cancer 2004;90(4):770–2. [CrossRef]

- Symer M.M., Wong N.N., Abelson J.J., Milsom J.J., Yeo H.H. Hormone Replacement Therapy and Colorectal Cancer Incidence and Mortality in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial. Clin. Colorectal Cancer 2018, 17, e281–e288. [CrossRef]

- Manson J, Aragaki AK, Rossouw JE, et al. Menopausal Hormone Therapy and Long-term All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality: The Women's Health Initiative Randomized Trials 2017, 318, 927–938. [CrossRef]

- Titan AL, He H, Lui N, et al. The influence of hormone replacement therapy on lung cancer incidence and mortality. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2020, 159, 1546-1556.e4. [CrossRef]

- Jin C, Lang B. Hormone replacement therapy and lung cancer risk in women: a meta-analysis of cohort studies: Hormone replacement therapy and lung cancer risk. Medicine 2019, 98, e17532.

- Hicks BM, Kristensen KB, Pedersen SA, et al. Hormone replacement therapy and the risk of melanoma in post-menopausal women. Human Reprod, 2019, 34, 2418-2429. [CrossRef]

- Botteri E, Støer NC, Weiderpass W, et al. Menopausal Hormone Therapy and Risk of Melanoma: A Nationwide Register-Based Study in Finland. Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2019, 28, 1857–1860. [CrossRef]

- Botteri E, Støer NC, Sakshaug S, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and risk of melanoma: Do estrogens and progestins have a different role? Int J Cancer 2017, 141, 1763–1770.

Table 1.

Study characteristics of included studies. Colorectal cancer.

Table 1.

Study characteristics of included studies. Colorectal cancer.

| Study |

Study Period |

Country |

Age |

Number of Participants |

Stage |

Grade |

HRT Type |

HRT Recency |

CRC Death HRT User vs no User |

All-Cause Mean DeathHRT User vs no User |

Mean Follow Up Year |

| Prospective cohort |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Slattery et al (1999)18

|

1991-1998 |

USA |

50-79 |

801 |

35.4% local, 53.2% regional, 11.4% distant |

NR |

E,

E + P

|

Current to stop less than 5 years |

504 (62,9)

297 (37,1)

0.6 (0.4±0.9) |

0.7 (0.5±0.9) |

4 |

| Mandelson et al (2003)16

|

1980-1998 |

USA |

50–79 |

699 |

NR |

NR |

E,E + P |

Current |

0.59 (0.35–0.97) |

0.77 (0.54–1.09) |

5.33 |

| Ji et al (2018)17

|

2006-2015 |

Sweden |

45-69 |

5626 |

23.7% stage I, 27.8% stage II, 36.2% stage III, 12.3% stage IV |

NR |

E,

E + P |

Current |

0.74 (0.62-0.88) p= 0.0006 |

0.70 (0.60-0.82) p<0.0001 |

5.4 |

| Retrospective cohort |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Chan et al (2006)14

|

1976-2004 |

USA |

62.2–65.7 |

834 |

22.3% stage I, 26.1% stage II, 25.5% stage III, 15.6% stage IV, 10.5% unknown |

22.3% stage I, 26.1% stage II, 25.5% stage III, 15.6% stage IV, 10.5% unknown |

E,

E + P

|

Current

former |

Current 0.64 (0.47-0.88) former 1.05 (0.79-1.40) |

Current 0.74 (0.56-0.97) former 1.00 (0.78-1.30) |

5-10 |

| Arem et al (2015)15

|

1995-2001 |

USA |

50,71 |

2053 |

30.5% localized, 31.3% regional or distant, 38.2% unknown |

12.0% well- differentiated, 57.5% moderate- differentiated, 0.9% undifferentiated, 29, 6% unknown |

E,

E + P

|

Current

former |

Current 0.76 (0.59, 0.97) former 1.03 (0.72, 1.47) |

Current 0.79 (0.66, 0.94) former 1.13 (0.89, 1.43) |

7.7 |

Table 2.

Study characteristics of included studies. Lung cancer.

Table 2.

Study characteristics of included studies. Lung cancer.

| Study |

Study period |

Country |

Age |

Number of participants |

Stage |

Smokers |

HRT Type |

Median overall survival |

Median overall survival with HTR

Smokers/no smokers |

| Retrospective cohort |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ganti et al (2006)19

|

1994-1999 |

USA |

31-93 |

498 |

I 26 %

II 21 %

IIIA 11 %

IIIB 8 %

IV 28 % |

86 % |

All types |

Never used

HRT 79 months; 95% CI, 65 to 95

months) HRT

39 months; 95% CI, 35 to 77 monthsP 0 .02 |

Smoke and HRT smoked and used / smoke and no HRT

39 v 73 months;

P 0 .03). No smoke and HRT / No smoke and not HRT92 v 98 NS |

| Ayeni et al (2009)20

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Katkoff et al (2014)21

|

2001-2005 |

USA |

17-74 |

485 |

Local 33,6 %

Regional 33,4 %

Distant 33,0 |

Current or former 92,3 % |

Estrogen only 99Estroge plus progesterone 85 |

Median survival time, HRT 80.0 mNo HRT 37.5 m p<0.001 |

Never smoker and HRT vs no HRT 17 (7.4) /

20 (7.9) Current smokers anh HTR vs no HRT 126 (54.8) / 165 (65.2)

NS |

| Huang et al (2009)22

|

1995-2005 |

USA |

37-90 |

648 |

I 20.8 %

II 4.8 %

III 30.1 %

IV 37.4 % Unknown stage 6.9 % |

61,9 % |

All types |

HRT / no HRT

16.4 v 10.5 NS

|

Smoke and HRT / no smoke and HRT

11.3 vs 16.9 months

P 0,03

Smoke and HRT / No smoke and HRT

NS |

| Prospective cohort |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Clague et al (2014)23

|

1995-1996 |

USA |

NR |

727 |

Localized 153

Regional 51

Lymph nodes 73

Regional and lymph nodes 33

Distant 365

Unknown 52 |

543 (74,69%) |

Estrogen 188

Estrogen + progesterone 176 |

HRT 21.4 m

No HRT 15,6 m

p=0.002 |

Ever MHT user vs never user

(HR)

Never smokers 1.23 (0.58–2.63)

Former smokers 0.74 (0.50–1.10)

Current smokers 0.44 (0.26–0.75) |

| Meta-analysis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Li et al (2020)24

|

|

|

|

No HRT 1054

HRT 1528 |

|

|

|

With HRT increased survival time for 5 years (ES=0.346; 95% CI 0.216 to 0.476; P<0.001). |

|

Table 3.

Study characteristics of included studies Melanoma.

Table 3.

Study characteristics of included studies Melanoma.

| Study |

Study period |

Country |

Age |

Number of participants |

Type |

HRT Type |

CRC death/ HRT user |

All-cause Mean death/HRT user |

Mean follow up year |

| Prospective cohort |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MacKie et al (2004)25

|

1990-1995 |

Scotland |

46-59 |

206 |

Ulceration

Yes 5 (6.2) 21 (17.8) 0.017*Patients with tumours o1mm thick 42 (50.6) 58 (47.2) 0.627*

Patients with

Superficial spreading melanoma 60 (73.2) 84 (69.4) 0.846*

Nodular/polypoid melanoma 15 (18.3) 25 (20.7)

Lentigo maligna melanoma 4 (4.9) 4 (4.3)

Acral/mucosal melanoma 1 (1.2) 2 (1.7)

Other and unspecified melanoma 2 (2.4) 6 (5.0) |

21 oestrogen

62 oestrogen/progesrterone |

HRT 1

No HRT 22 |

HRT 0

No HRT 4 |

19 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).