Submitted:

20 June 2023

Posted:

21 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

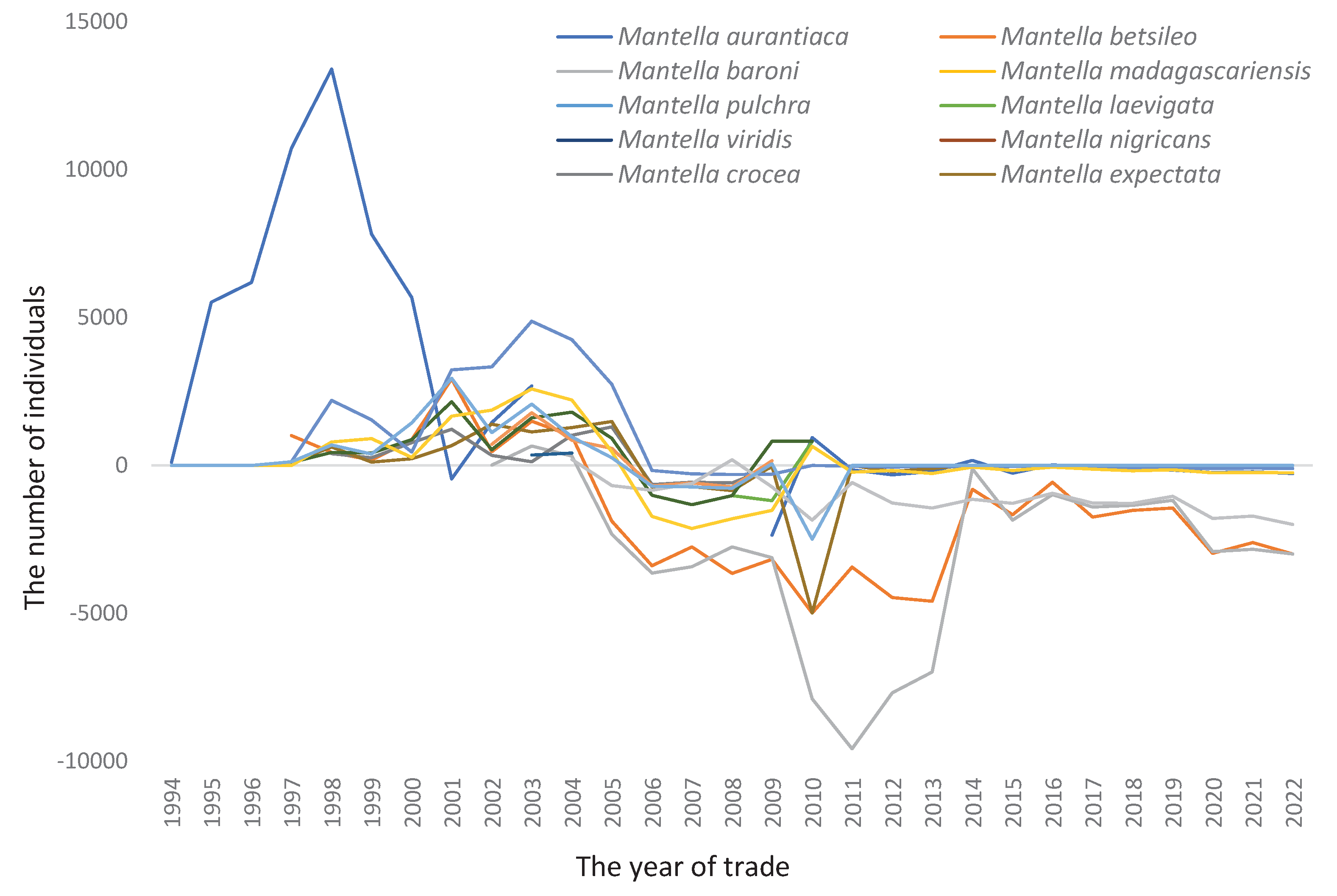

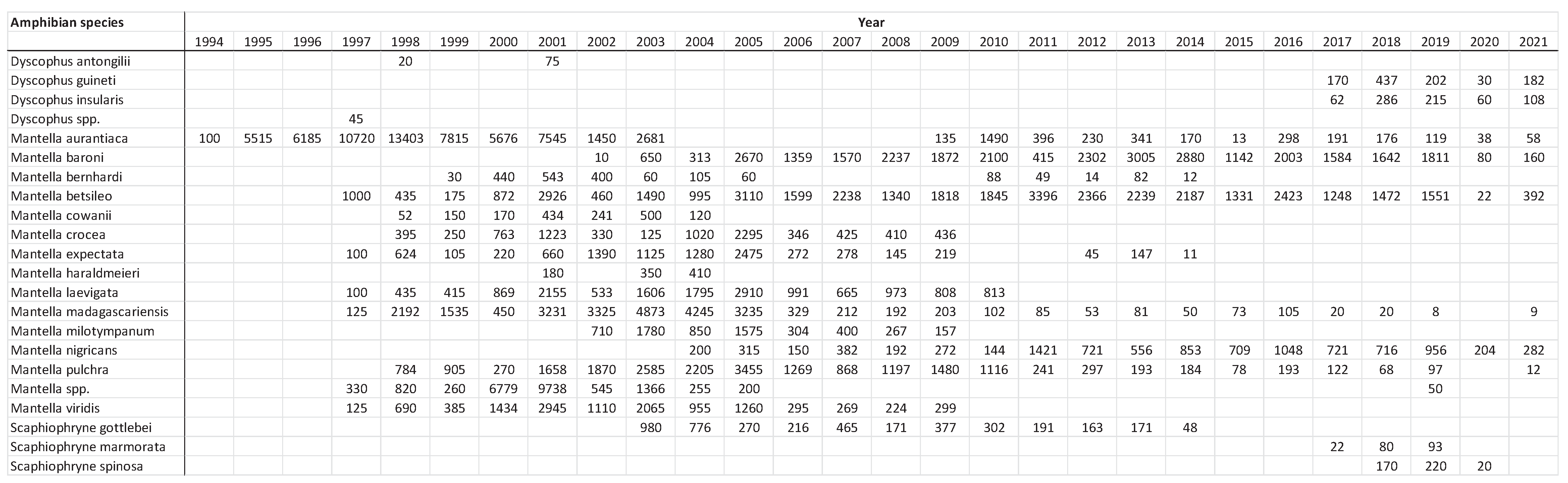

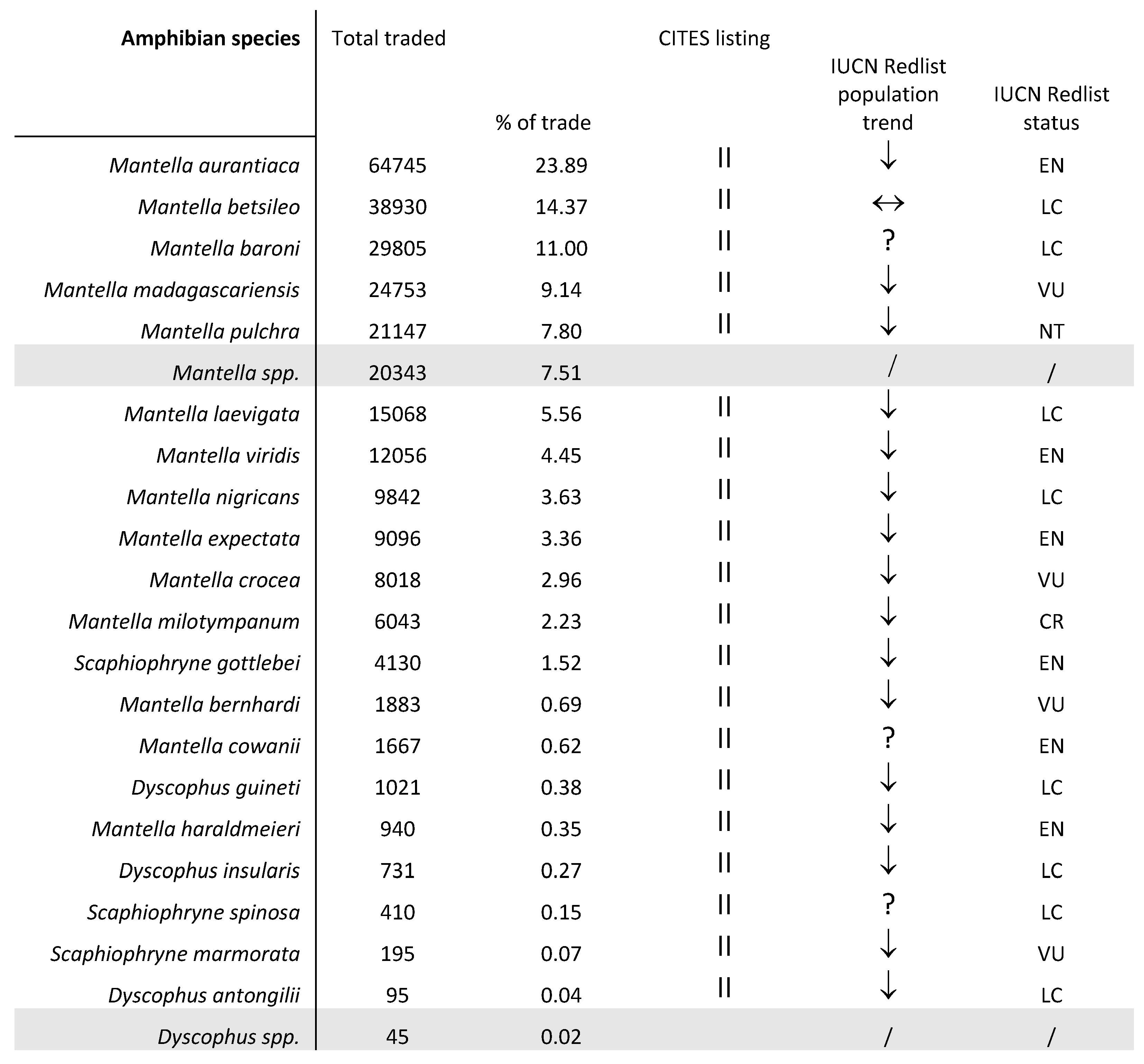

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cowie, R.H.; Bouchet, P.; Fontaine, B. The Sixth Mass Extinction: fact, fiction or speculation? Biol. Rev., 2022, 97, 640–663. [CrossRef]

- IPBES. Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; IPBES secretariat: Bonn, Germany, 2019. https://ipbes.net/global-assessment (accessed on 15 Jan 2023).

- Jeliazkov, A.; Gavish, Y.; Marsh, C.J.; Geschke, J.; Brummitt, N.; Rocchini, D.; Haase, P.; Kunin, W.E.; Henle, K. Sampling and modelling rare species: Conceptual guidelines for the neglected majority. Global Change Biology, 2022, 28, 3754– 3777. [CrossRef]

- Gascon, C.; Collins, J.P.; Moore, R.D.; Church, D.R.; McKay, J.E.; Mendelson, J.R. III, Eds; Amphibian Conservation Action Plan. IUCN/SSC Amphibian Specialist Group. Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK, 2007, 64; ISBN: 978-2-8317-1008-2.

- Andreone, F.; Loarie, S.R.; Pala, R.; Luiselli, L.M.; Carpenter, A.I. Trade and exploitation of amphibians and reptiles: A short overview of the conservation impacts. Zoologia, 2012, 146, 85–93.

- Mims, M.C.; Drake, J.C.; Lawler, J.J.; Olden, J.D. Simulating the response of a threatened amphibian to climate-induced reductions in breeding habitat. Landsc Ecol, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wetsch, O.; Strasburg, M.; McQuigg, J.; Boone, M.D. Is overwintering mortality driving enigmatic declines? Evaluating the impacts of trematodes and the amphibian chytrid fungus on an anuran from hatching through overwintering. PLOS ONE, 2022, 17, e0262561. [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, A.I.; Andreone, F.; Moore, R.D.; Griffiths, R.A. A review of the global trade in amphibians: The types of trade, levels and dynamics in CITES listed species. Oryx, 2014, 48, 565–574.

- Goodman, S.M., Ed; The new natural history of Madagascar. Princeton University Press, Princeton, US, 2022; ISBN 9780691222622.

- Glaw, F.; Crottini, A.; Rakotoarison, A.; Scherz, M.D.; Vences, M., Diversity and exploration of the Malagasy amphibian fauna. In The new natural history of Madagascar; Goodman, S.M., Ed; Princeton University Press, Princeton, US, 2022; Volume 2, 1305-1322; ISBN 9780691222622. [CrossRef]

- Riemann, J.C.; Crottini, A.; Lehtinen, R.M.; Ndriantsoa, S.H.; Rödel, M.O.; Vallan, D.; Glos, J., Consequences of forest fragmentation and habitat alterations for amphibians. In The new natural history of Madagascar; Goodman, S.M., Ed; Princeton University Press, Princeton, US, 2022; Volume 2, 1336-1641; ISBN 9780691222622. [CrossRef]

- Irwin, M.T.; Wright, P.C.; Birkinshaw, C.; Fisher, B.F.; Gardner, C.J.; Glos, J.; Goodman, S.M.; Loiselle, P.; Rabeson, P.; Raharison, J-L.; Raherilalao, M.J.; Rakotondravony, D.; Raselimanana, A.; Ratsimbazafy, J.; Sparks, J.S.; Wilmé, L.; Ganzhorn, J.U., Patterns of species change in anthropogenically disturbed forests of Madagascar, Biological Conservation, 2010, 143, 2351-2362. [CrossRef]

- Bletz, M.; Crottini, A.; Weldon, C.; Vences, M.; Rabemananjara, F.C.E.; Fisher, M.; Du Preez, L., Amphibian diseases and parasites. In The new natural history of Madagascar; Goodman, S.M., Ed; Princeton University Press, Princeton, US, 2022; Volume 2, 1342-1349; ISBN 9780691222622.

- Bletz, M.; Rosa, G.; Andreone, F.; Courtois, E.A.; Schmeller, D.S.; Rabibisoa, N.H.C.; Rabemananjara, F.C.E.; Raharivololoniaina, L.; Vences, M.; Weldon, C.; Edmonds, D.; Raxworthy, C.J.; Harris, R.N.; Fisher, M.C.; Crottini, A., Widespread presence of the pathogenic fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis in wild amphibian communities in Madagascar. Sci Rep., 2015, 5, 8633. [CrossRef]

- Fulvio, L.; Ficetola, G.F.; Freeman, K.; Mahasoa, R.H.; Ravololonarivo, V.; Solofo Niaina Fidy, J.F.; Koto-Jean, A.B.; Nahavitatsara, E.R.; Andreone, F.; Crottini, A., Abundance, distribution and spread of the invasive Asian toad Duttaphrynus melanostictus in eastern Madagascar. Biological Invasions, 2019, 21, 1615-1626. [CrossRef]

- Andreone, F.; Carpenter, A.I.; Crottini, A.; D’Cruze, N.; Dubos, N.; Edmonds, D.; Garcia, G.; Luedtke, J.; Megson, S.; Rabemananjara, F.C.E.; Randrianantoandro, J.C.; Randrianavelona, R.; Robinson, J.; Vallan, D.; Rosa, G.M., Amphibian conservation in Madagascar: Old and novel threats to a peculiar fauna. In Status and Threats of Afrotropical Amphibians—Sub-Saharan Africa, Madagascar, Western Indian Ocean Islands; Heatwole, H, Rödel, M.O., Eds; Chimaira, Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2021, Amphibian Biology, 11, 147-187. ISSN 1613-2327.

- Carpenter, A.I.; Robson, O., Madagascan amphibians as a wildlife resource and their potential as a conservation tool: species and numbers exported, revenue generation and bio-economic models to explore conservation benefits, In Andreone, F, Ed; Conservation Strategy for the Amphibians of Madagascar proceedings, Monografie del Museo Regionale di Scienze Natural di Torino, 2008, 357-376.

- Rabemananjara, F.C.E.; Raminosoa, N.R.; Ramilijaona, O.R.; Rakotondravony, D.; Andreone, F.; Bora, P.; Carpenter, A.I.; Glaw, F.; Razafindrabe, T.; Vallan, D.; Vieites, D.R.; Vences, M., Malagasy poison frogs in the pet trade: a survey of levels of exploitation of species in the genus Mantella, In Conservation Strategy for the Amphibians of Madagascar proceedings, Ed Andreone, F.; Monografie del Museo Regionale di Scienze Natural di Torino, 2008, 277-300.

- Rabemananjara, F.C.E.; Raminosoa, N.R.; Ramilijaona, O.R.; Andreone, F.; Bora, P.; Carpenter, A.I.; Glaw, F.; Razafindrabe, T.; Vallan, D.; Vieites, D.R.; Vences, M., Malagasy poison frogs in the pet trade: a survey of levels of exploitation of species in the genus Mantella. Amphibian & Reptile Conservation, 2007, 5: 3-16.

- Carpenter, A.I.; Dublin, H.; Lau, M.; Syed, G.; McKay, J.E.; Moore, R.D, Over-harvesting, In Amphibian Conservation Action Plan, Eds, Gascon, C.; Collins, J.P.; Moore, R.D.; Church, D.R.; McKay, J.E.; Mendelson III, J.R.; Proceedings: IUCN/SSC Amphibian Conservation Summit 2005, Gland, Switzerland, 2007, Chapter 5, 26-31.

- Carpenter, A.I.; Rabemananjara, F.C.E.; Behra, O.; Raselimanana, A.P.; Ratsoavina, F.M.; Wollenberg-Valero, K.C.; D’Cruze, N., Valourization of reptiles and amphibians from the wildlife trade and ecotourism, In The new natural history of Madagascar, Ed., Goodman, S. M.; Princeton University Press, Princeton, USA, 2022, 1452-1455.

- Carpenter, A.I.; Slade, J. A, Review of the Trade in Toucans (Ramphastidae): Levels of Trade in Species, Source and Sink Countries, Effects from Governance Actions and Conservation Concerns, Conservation, 2023, 3, 153–174. [CrossRef]

- Braunschneider, T., The Lady and the Lapdog: Mixed Ethnicity in Constantinople, Fashionable Pets in Britain. In Humans and Other Animals in Eighteenth-Century British Culture, Palmeri, F., Ed; Routledge, London, UK, 2006, Chapter 2, ISBN 9781315252896.

- Valdez, J.W.; Using Google Trends to Determine Current, Past, and Future Trends in the Reptile Pet Trade. Animals, 2021, 11, 676. [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, A.I. The Ecology and Exploitation of Chameleons in Madagascar. Ph.D. Thesis, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK, 2003.

- Carpenter, A.I.; Robson, O.; Rowcliffe, M.; Watkinson, A.R. The impacts of international and national governance on a traded resource: A case study of Madagascar and its chameleon trade. Biol. Conserv. 2005, 123, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, A.I.; Robson, O.; Rowcliffe, M.; Watkinson, A.R. The impacts of international and national governance on a traded resource: A case study of Madagascar and its chameleon trade. Biol. Conserv. 2005, 123, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU. Council Regulation (EC) No 338/97 of 9 December 1996 on the protection of species of wild fauna and flora by regulating trade therein; Official Journal of the European Communities, 1997, 61 /1, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ:L:1997:061:TOC. 9 December.

- EU. COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) 2019/1587 of 24 September 2019. Official Journal of the European Union, 2019, 248/5, EUR-Lex - 31997R0338 - EN - EUR-Lex (europa.eu). 24 September.

- Andreone, F.; Carpenter, A.I.; Cox, N.; du Preez, L.; Freeman, K.; Furrer, S.; Garcia, G.; Glaw, F.; Glos, J.; Knox, D.; Kohler, J.; Mendelson III, J.R.; Mercurio, V.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Moore, R.D.; Rabibisoa, N.H.C.; Randriamahazo, H.; Randrianasolo, H.; Raminosoa, N.R.; Ramilijaono, O.R.; Raxworthy, C.J.; Vallan, D.; Vences, M.; Vieites, D.R.; Weldon, C. The challenge of conserving amphibian megadiversity in Madagascar. PLoS Biology, 2008, 6: 1-4.

- Andreone, F.; Carpenter, A.I.; Copsey, J.; Crottinid, A.; Garciac, G.; Jenkins, R.; Köhlerg, J.; Rabibisoah, N.; Randriamahazoi, H.; Raxworthy, C.J. Saving the diverse Malagasy amphibian fauna: where are we four years after implementation of the Sahonagasy Action Plan? Alytes, 2012, 29: 43-58.

- Crottini, A.; Ndriantsoa, S.H.; Rakotoarison, A.; Rakotonanahary, T.F.; García, G.; Rabibisoa, N.H.C; Andreone, F., Amphibian conservation through the implementation of ‘A conservation strategy for the amphibians of Madagascar – ASCAM’. In The new natural history of Madagascar, Goodman, S.M., Ed; Princeton University Press, Princeton, US, 2022; Volume 2, 1326-1330; ISBN 9780691222622.

- CITES, Conservation of amphibians (Amphibia spp.). Nineteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties, Panama City, Panama, 14-25 November, 2022, CoP19 Doc. 60; https://cites.org/sites/default/files/documents/E-CoP19-60.pdf [accessed 25/02/2023].

- van den Burg, M.P.; Weissgold, B.J. Illegal trade of morphologically distinct populations prior to taxonomic assessment and elevation, with recommendations for future prevention. J. Nat. Conserv. 2020, 57, 125887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database Field | Search Input |

|---|---|

| Search date | 25/02/2023 |

| Year range | 1975 - 2022 |

| Exporting countries | Madagascar |

| Importing countries | All countries |

| Source | Wild (W), Ranched (R), Source unknown (U) |

| Purpose | Commercial (T), Breeding in captivity or artificially propagation (B), Botanical garden (G), Circus & travelling exhibitions (Q), Personal (P) |

| Trade terms | Live (LIV), Specimens (SPE), Bodies (BOD) |

| Taxon | Amphibia (Amphibians) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).