Submitted:

21 June 2023

Posted:

22 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Fear of Missing Out (FoMO)

1.2. Cognitive Load

1.3. Online Shopping Addiction

1.4. Personality Type

| Type A Personality Structure | Type B Personality Structure |

|---|---|

| They are always in action. | It has little to do with time. |

| They walk fast. | They are patient. |

| Fast places. | They don't like to brag. |

| They talk fast. | They do games and sports for fun, not to win. |

| They are impatient. | They rest comfortably. |

| They do two things at once. | They are not under pressure to get the job done right away. |

| They do not have much free time. | They are soft headed. |

| They are obsessed with numbers. | They never rush. |

| Numbers tend to measure success. | |

| They are aggressive. | |

| They are competitive. | |

| They are under constant time pressure. |

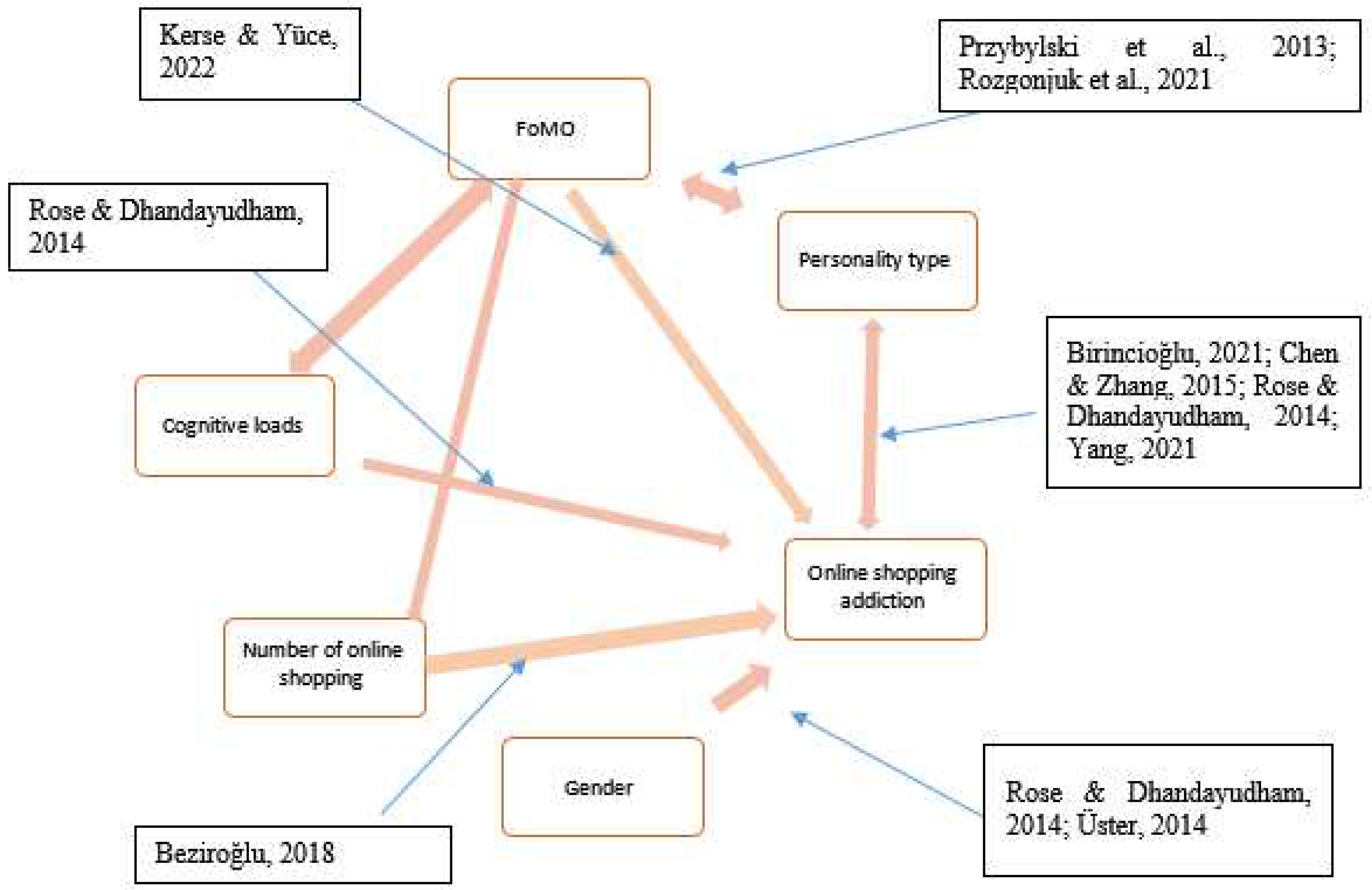

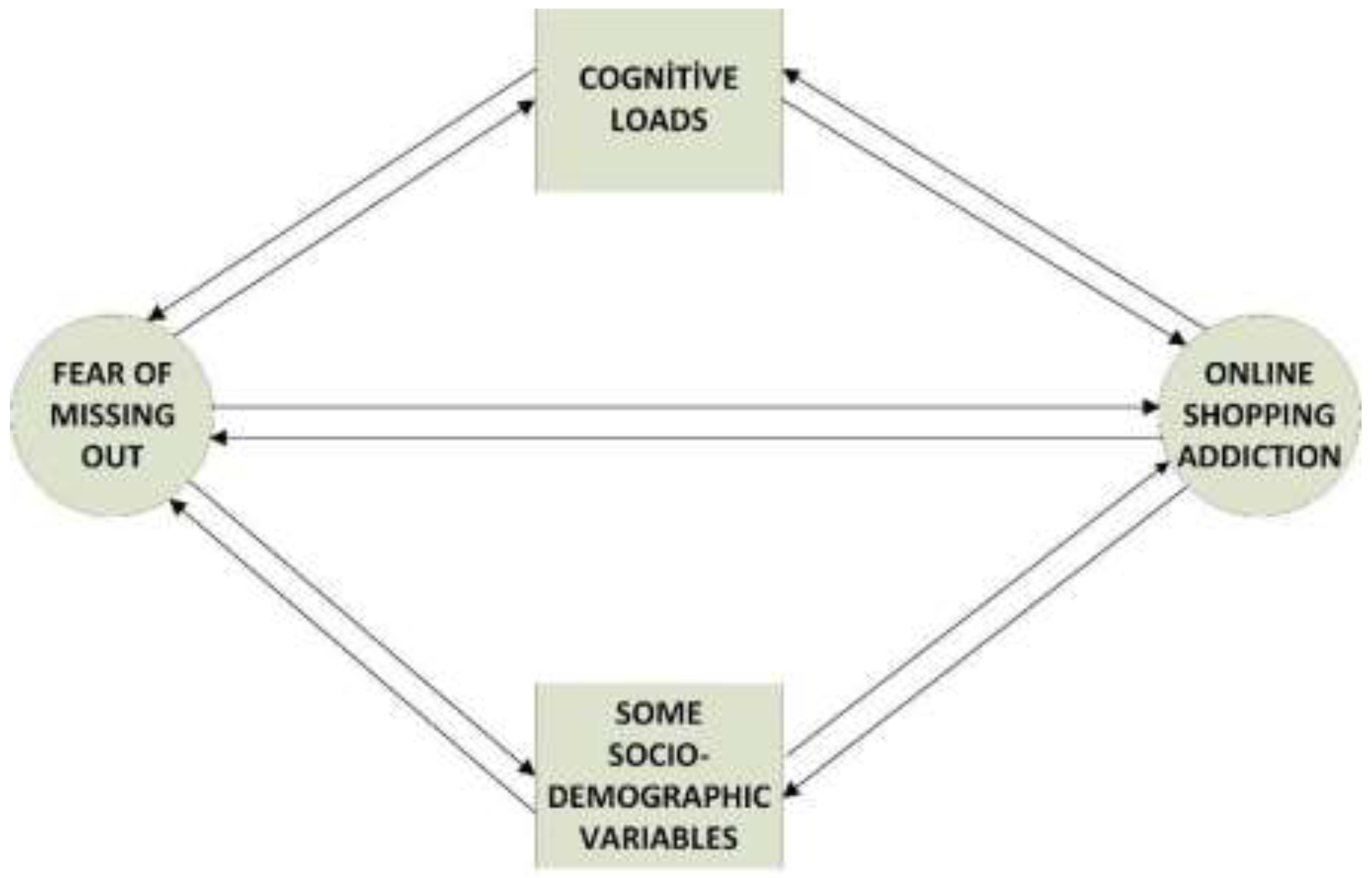

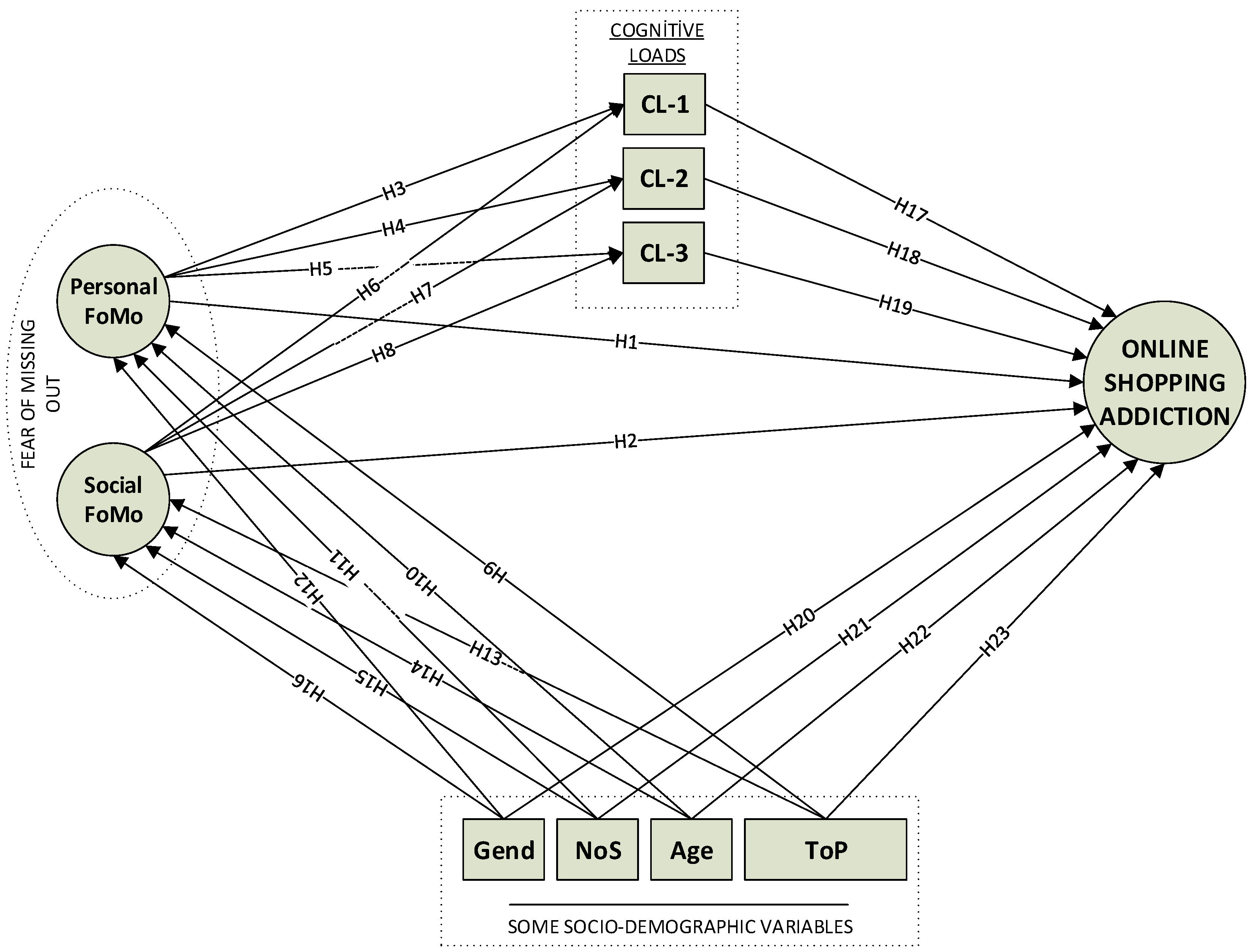

1.5. Purpose of The Study

2. Method

2.1. The Universe and Sample

2.2. Data Collection Tools

2.1.1. FoMO Scale

2.1.2. Cognitive Load Scale

- To what extent do you exert effort in searching for the product you want to buy?

- How much effort do you invest in the shopping process?

- How much effort do you dedicate to the payment process?

- Anticipation: Individuals experience expectations, personal emotions, and desires that drive them to shop.

- Preparation: They engage in activities such as deciding where to go, what to wear, and which credit cards to use in preparation for shopping and spending.

- Shopping: This is considered the most crucial stage, where individuals may experience temporary relief, intense excitement, or even sexual arousal.

- Spending: Shortly after making the purchase, individuals may start feeling frustrated or regretful about their actions.

2.1.3. Online Shopping Addiction Scale

2.1.4. Personality Inventory

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

- The theory was developed by reviewing the existing literature.

- The model associated with the theory was identified and visually represented.

- The sample for the study was determined, and data were collected using specific measurement scales.

- The model's accuracy was assessed through path analysis.

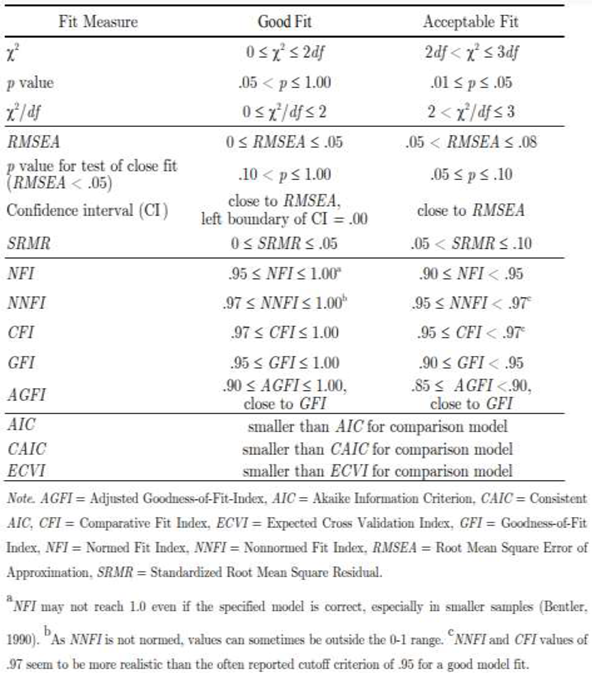

- Based on the analysis results, the model's compatibility was examined using goodness-of-fit indices. If inconsistencies were found, modifications were made to the model, which was then finalized and reported.

|

3. Findings and Comment

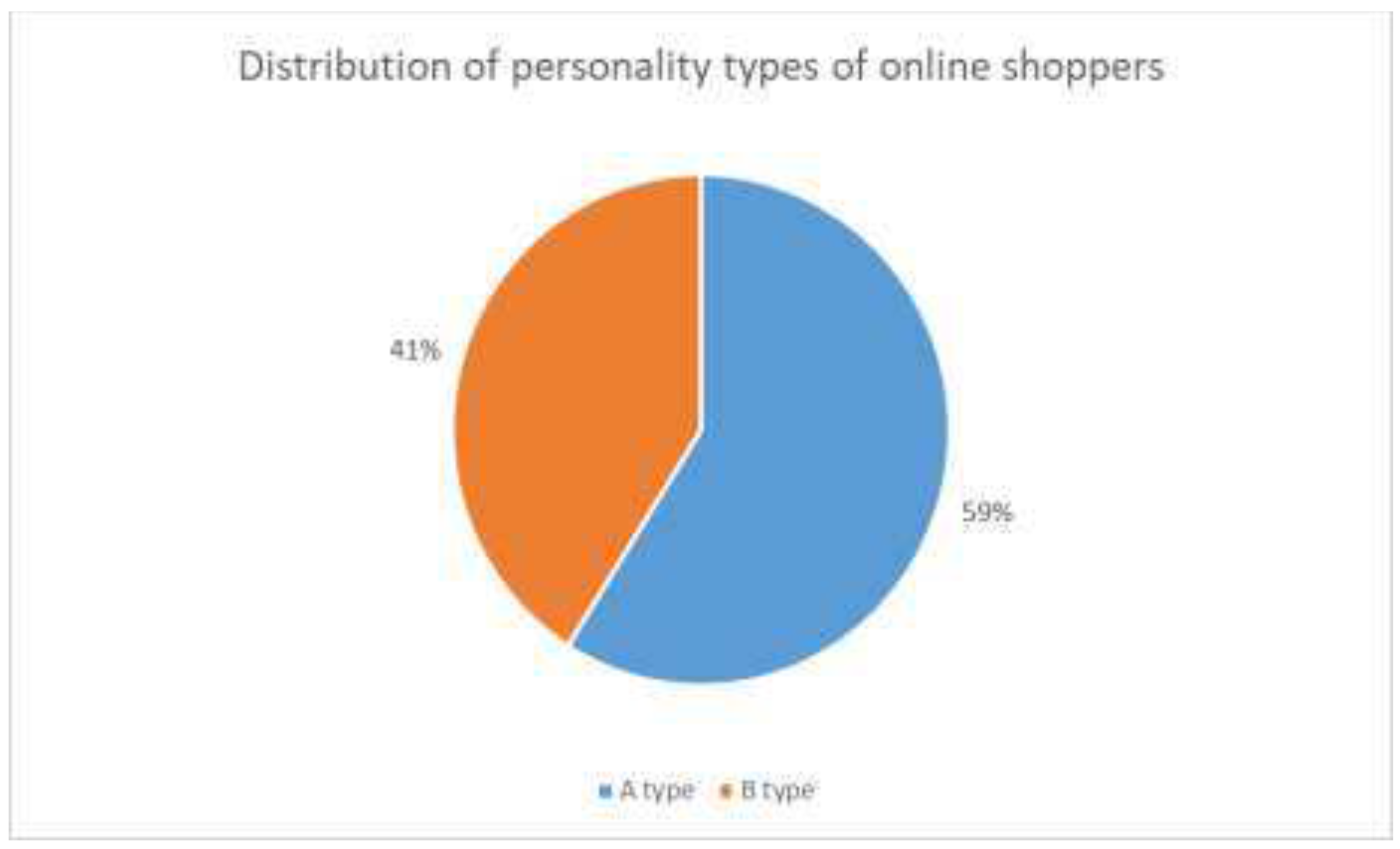

3.1. Findings Describing The Participants

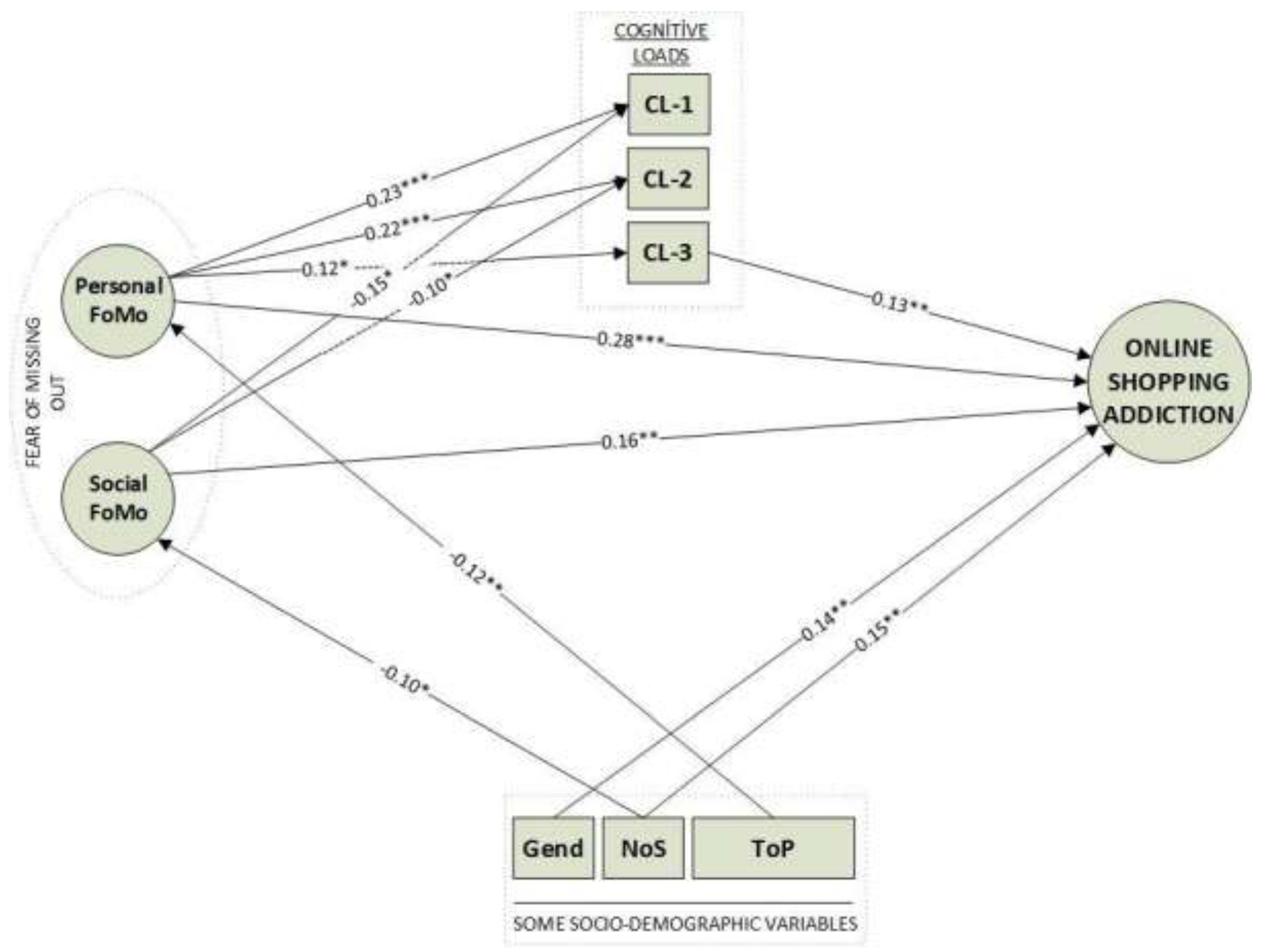

3.2. Findings on The Model

4. Conclusions, Discussion and Recommendations

- Free delivery (57.3%)

- Easy return policy (49.4%)

- Coupons and discounts (43.5%)

- Fast and easy payment (34.8%)

- Customer comments (34.7%)

- Next day delivery (34.2%)

- Likes or positive comments on social media accounts (27.1%)

- Cash on delivery option (26.4%)

- Loyalty points (26.0%)

- Company appearing environmentally friendly (21.6%)

- Interest-free payment option (21.1%)

- Live chat support (19.5%)

- Membership-free ordering feature (18.9%)

- In-store pickup option (17.9%)

- Exclusive content or services (15.8%)

Author Contributions

Funding

References

- Abel, J. P., Buff, C. L., & Burr, S. A. (2016). Social media and the fear of missing out: Scale development and assessment. Journal of Business & Economics Research (JBER), 14(1), 33-44. [CrossRef]

- Algür, S., & Cengiz, F. (2011). Türk tüketicilere göre online (çevrimiçi) alışverişin riskleri ve yararları [The risk and benefit perceptions of online shopping according to the Turkish consumers]. Journal of Yaşar University, 6(22), 3666-3680.

- Alkış, N. (2016). BAYES yapısal eşitlik modellemesi: Kavramlar ve genel bakış [BAYESIAN structural equation modeling: Concepts and a general overview]. Gazi İktisat ve İşletme Dergisi [Gazi Journal of Economics and Business], 2(3), 105-116.

- Alt, D. (2015). College students’ academic motivation, media engagement and fear of missing out. Computers in Human Behavior, 49, 111-119. [CrossRef]

- Argan, M., Tokay Argan, M., & İpek, G. (2018). I wish I were! Anatomy of a fomsumer [Keşke olsaydım! Bir fomo tüketicinin (fomsumer) anatomisi]. İnternet Uygulamaları ve Yönetimi Dergisi [Journal of Internet Applications and Management], 9(1), 43-57. [CrossRef]

- Argan, M., & Tokay-Argan, M. (2018). Fomsumerism: A theoretical framework. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 10(2), 109-117. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, A., & Kotler, D. (2015). Principles of Marketing 6e. Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd.

- Aslan, S., (2008). Kişilik, huy ve psikopatoloji [Personality, temperament and psychopatology]. Psikiyatride Derlemeler, Olgular ve Varsayımlar [Reviews, Cases and Hypotheses in Psychiatry], 2(1-2), 7-18.

- Aydın, B. (2022). Dijital pazarlamada online kullanıcı deneyimi: anne bebek sektörü örneği [Online user experience in digital marketing: The case of the mother-baby industry] (Unpublished master’s thesis). Maltepe University Social Sciencens Graduate School.

- Bal, F., & Okkay, İ. (2022). İnternet tabanlı sorunlu alışveriş davranışı: Çevrimiçi alışveriş bağımlılığı [Internet-based problem shopping behavior: Online shopping addiction]. Bağımlılık Dergisi [Journal of Dependence], 23(1), 111-120. [CrossRef]

- Balcı, A. (2009). Sosyal bilimlerde araştırma yöntem, teknik ve ilkeleri [Research methods, techniques and principles in Social Sciences] (7th ed.). Pegem Akademi Publishing.

- Bekman, M. (2022). The effect of FoMO (Fear of Missing Out) on purchasing behavior in public relations practices. Journal of Selçuk Communication, 15(2), 528-557. [CrossRef]

- Beziroğlu, M. (2018). Kompulsif satın alma, bilişsel duygu düzenleme ve davranışsal inhibisyon, davranışsal aktivasyon sistemi arasındaki ilişkiler [Relationship between compulsive buying, cognitive emotion regulation, behavioral inhibition and behavioral activation system]. (Unpublished master’s thesis) Maltepe University Institute of Social Sciences.

- Birincioğlu, F. N. (2021). Alışveriş bağımlılığı ve kişilik tipleri arasındaki ilişkinin incelenmesi [Examining the relationship between shopping addiction and personality types]. (Unpublished master’s thesis). İstanbul Sabahattin Zaim Üniversitesi Lisansüstü Eğitim Enstitüsü [Istanbul Sabahattin Zaim University Graduate School of Education].

- Black, D. W. (2007). Compulsive buying disorder: A review of the evidence. CNS Spectrums, 12(2), 124-132. [CrossRef]

- Bortner, R. W. (1969). A short rating scale as a potential measure of pattern a behavior. Journal of Chronic Diseases, 22(2), 87-91. [CrossRef]

- Bulunmaz, B. (2016). Gelişen teknolojiyle birlikte değişen pazarlama yöntemleri ve dijital pazarlama [Evolution in marketing methods with developing technology and digital marketing] TRTAkademi, 1(2), 348-365.

- Büyüköztürk, Ş., Kılıç Çakmak, E., Akgün, Ö. E., Karadeniz, Ş., & Demirel, F. (2016). Bilimsel araştırma yöntemleri [Scientific research methods] (21st ed.). Pegem Akademi Publishing.

- Caldiroli, C. L., Gasparini, F., Corchs, S., Mangiatordi, A., Garbo, R., Antonietti, A., & Mantovani, F. (2022). Comparing online cognitive load on mobile versus PC-based devices. Personel and Ubiquitous Computing, 27, 495-505. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., & Zhang, L. (2015). Influential factors for online impulse buying in China: A model and its empirical analysis. International Management Review, 11(2), 57-60.

- Činjarević, M. (2010). Cognitive and affective aspects of impulse buying. Sarajevo Business and Economics Review, 30, 168-184.

- Civek, F., & Ulusoy, G. (2020). X ve Y kuşağı tüketicilerin nomofobik eğilimlerinin çevrimiçi alışveriş bağımlılığı ile olan ilişkisinin belirlenmesi [Determining the relationship between nomophonic intentions of X and Y generation consumers and online Marketing]. Turkish Studies-Social, 15(1), 141-156. [CrossRef]

- Çelik, F., & Özkara, B. Y. (2022). Gelişmeleri kaçırma korkusu (FoMO) ölçeği: Sosyal medya bağlamına uyarlanması ve psikometrik özelliklerinin sınanması [Fear of Missing Out (FoMO) scale: Adaptation to social media context and testing its psychometric properties]. Psikoloji Çalışmaları [Studies in Psychology], 42(1), 71-103. [CrossRef]

- Çetin N. G., & Beceren, E. (2007). Lider kişilik: Gandhi. Süleyman Demirel Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi. 3(5), 110-132.

- Deloitte.Digital & TÜSİAD. (2022). E-ticaretin öne çıkan başarısı, tüketici davranışlarında değişim ve dijitalleşme [The outstanding success of e-commerce, change in consumer behavior and digitalization]. Deloitte.Digital. 1-138.

- Doğan Keskin, A., & Günüç, S. (2017). Testing models regarding online shopping addiction. Addicta: The Turkish Journal on Addictions, 4(2), 221-242. [CrossRef]

- Durna, U. (2005). A Tipi ve B Tipi kişilik yapıları ve bu kişilik yapılarını etkileyen faktörlerle ilgili bir araştırma [A research on Type A and Type B personality structures and the factors affecting these personality structures]. Atatürk Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Dergisi [Journal of Economics and Administrative Sciences], 19(1), 275-290.

- Fırın, S., & Sevim, Ş. (2022). Kişilik özelliklerinin yenilikçi davranış etkisi üzerine bir araştırma [A research on the effect of personality traits on innovative behavior]. İşletme Araştırmaları Dergisi [Journal of Busıness Research-Türk], 14(2), 1189-1200. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M., & Rosenman, R. H. (1959). Association of specific overt behavior pattern with blood and cardiovascular findings: Blood cholesterol level, blood clotting time, incidence of arcus senilis, and clinical coronary artery disease. Journal of the American Medical Association, 169(12), 1286-1296. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M., & Rosenman, R. H. (1974). Type A behavior and your heart. Knopf.

- Griffin, R. W., & Moorhead, G. (2014). Organizational Behavior: Managing People and Organizations (Eleventh Edition). South-Western, Cengage Learning.

- Griffiths, M. (2005). A “components” model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. Journal of Substance Use, 10(4), 191-197. [CrossRef]

- Günüç, S., & Doğan Keskin, A. (2016). Online shopping addiction: Symptoms, causes and effects. Addicta: The Turkish Journal on Addictions, 3(3), 353-364. [CrossRef]

- Güven, A. (2021). Multidisipliner bir kavram olarak “Fear of missing out” (Fomo): Literatür taraması [Fear of missing out (Fomo) as a multidisciplinary concept: Literature review]. Hatay Mustafa Kemal Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi [Mustafa Kemal University Journal of Social Sciences Institute], 18(48), 99-124.

- Hair Jr., J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2014). Multivariate Data Analysis (Seventh Edition, Pearson New International Edition). Pearson Education Limited.

- İşcan, R. V., Kapusuz, N., Bazancır, S., Bayram, İ., & Durukan, T. (2022). Sosyal medya fenomen bağlılığının tüketicilerin kaçırma korkusu (FoMO) ve satın alma niyetlerine etkisi [The effect of social media phenomena commitment on consumers' fear of missing out (FoMO) and purchase ıntention]. International Academic Social Resources Journal, 7(42), 1219- 1228. [CrossRef]

- Kandell, J. J. (1998). Internet addiction on campus: The vulnerability of college students. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 1(1), 11-17. [CrossRef]

- Karagöz, Y. (2016). SPSS 23 ve AMOS 23 Uygulamalı İstatistiksel Analizler [SPSS 23 and AMOS 23 Applied Statistical Analysis]. Nobel Akademik Publishing.

- Kemp, S. (2023, 26 January). Digital 2023: Global overview report. Datareportal. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2023-global-overview-report.

- Kerse, Y., & Yüce, A. (2022). FoMO ve online kompulsif satın alma: Sosyal medya fenomenleri tüketicilerin kaygılarını ve takıntılarını tetikliyor mu? [FoMO and online compulsive buying: Do social media ınfluencers trigger consumers' anxiety and obsession?]. Karamanoğlu Mehmetbey Üniversitesi (KMÜ) Sosyal ve Ekonomik Araştırmalar Dergisi [KMU Journal of Social and Economic Research], 24(43), 704-716.

- Kılıç Çakmak, E. (2007). Çoklu ortamlarda dar boğaz: Aşırı bilişsel yüklenme [The bottle neck in multimedia: Cognitive overload]. Gazi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi [Gazi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi], 27(2), 1-24.

- Kılıç, E., & Karadeniz, Ş. (2004). Hiper ortamlarda öğrencilerin bilişsel yüklenme ve kaybolma düzeylerinin belirlenmesi [Specifying students' cognitive load and disorientation level in hypermedia]. Kuram ve Uygulamada Eğitim Yönetimi Dergisi [Educational Administration in Theory & Practice], 40, 562-579.

- Korkmaz, İ., & Dal, N. (2020). Bireysel yenilikçiliğin tüketici yenilikçiliğine etkisinde fomo’nun aracılık rolü [The mediating role of FoMO in the effect of individual innovativeness on consumer innovativeness]. Pazarlama ve Pazarlama Araştırmaları Dergisi [The Journal of Marketing and Marketing Research], 13(3), 532-567.

- Kuss, D. J., Griffiths, M. D., & Binder, J. F. (2013). Internet addiction in students: Prevalence and risk factors. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 959–966.

- Leblebicioğlu, B., & Aysuna Türkyılmaz, C. (2022). Understanding the moderator role of COVID-19 pandemic anxiety on the relationship between internet addiction and online shopping addiction. Marmara Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Dergisi [Marmara University Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences ], 44(1), 104-118. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Ma, X., Fang, J., Liang, G., Lin, R., Liao, W., & Yang, X. (2023). Student stress and online shopping addiction tendency among college students in Guangdong Province, China: The mediating effect of the social support. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 176. [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F. (1995). Organizational Behaviour. Literatür Publications.

- Luthans, F. (2011). Organizational Behavior: An evidence-based approach (12th Edition). McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

- Mantovani, F. (2001). Cyber-attraction: The emergence of computer-mediated communication in the development of interpersonal relationships. In L. Anolli, R. Ciceri, & G. Riva (Eds.), Say not to say: New perspectives on miscommunication (pp. 236-250). IOS Press.

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-396. [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A. H. (1958). A Dynamic Theory of Human Motivation. In C. L. Stacey & M. DeMartino (Eds.), Understanding human motivation (pp. 26-47). Howard Allen Publishers. [CrossRef]

- Mavili Aktaş, A. (2001). Bir kamu kuruluşunun üst düzey yöneticilerinin iş stresi ve kişilik özellikleri [Stress levels and characteristics of personalities of top level managers of the government sector]. Ankara Üniversitesi Siyasal Bilgiler Fakültesi Dergisi [Ankara Univerity SBF Journal], 56(4), 25-42. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, C., & Cotten, S. (2003). The relationship between internet activities and depressive symptoms in a sample of college freshmen. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 6(2), 133-142. [CrossRef]

- Mount, M. K., Barrick, M. R., Scullen, S. M., & Rounds, J. (2005). Higher-order dimensions of the big five personality traits and the big six vocational interest types. Personal Psychology, 58(2), 447-478. [CrossRef]

- Mutlu, T. (2021). Sosyal medya bağımlılığı ve kişilik ilişkisi: Sosyal medya üzerinden bir uygulama [Social media addiction and personality relationship: An application through social media]. (Unpublished master’s thesis). Sakarya Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü [Sakarya University Institute of Social Sciences].

- Müller, A. (2007). Kaufsucht/Pathologisches Kaufen: Weit verbreitet, wenig erforscht. Deutsches Ärzteblatt, 10, 468-469.

- Özçelik A. B., Gegez, E. E., & Burnaz, Ş. (2017). Mobil internet, tüketici materyalizmi ve alışveriş bağımlılığı: Alışveriş motivasyonlarının düzenleyici etkisi üzerine bir araştırma [Mobile internet, consumer materialism, and compulsive buying: An examination of the moderating role of shopping motivations]. Pazarlama Teorisi ve Uygulamaları Dergisi [Journal of Theory and Practice in Marketing], 3(2), 1-20.

- Özsoy, E. (2013). A tipi ve B tipi kişilik ile iş tatmini arasındaki ilişkinin belrlenmesne yönelik br araştırma [A research on determining the relationship between type A and type B personality and job satisfaction.]. (Unpublished master’s thesis). Sakarya Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü.

- Paas, F. G. W. C., Renkl, A., & Sweller, J. (2004). Cognitive load theory: Instructional implications of the interaction between information structures and cognitive architecture. Instructional Science 32, 1-8.

- Paas, F. G. W. C., & Van Merriȅnboer, J. J. G. (1993). The efficiency of instrutional conditions: An approach to combine mental effort and performance measures. Human Factors, 35(4), 737-743.

- Paas, F. G. W. C., & Van Merriȅnboer, J. J. G. (1994). Instructional control of cognitive load in the training of complex cognitive tasks. Educational Psychology Review, 6(4), 351-371.

- Paas, F., Tuovinen, J. E., Tabbers, H., & Van Gerven, P. W. M. (2003). Cognitive load measurement as a means to advance cognitive load theory. Educational Psychologist, 38(1), 63-71.

- Pontes, H. M., Szabo, A., & Griffiths, M. D. (2015). The impact of Internet-based specific activities on the perceptions of Internet addiction, quality of life, and excessive usage: A cross-sectional study. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 1, 19-25. [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, A. K., Murayama, K., DeHaan, C. R., & Gladwell, V. (2013). Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1841-1848. [CrossRef]

- Rose, S., & Dhandayudham, A. (2014). Towards an understanding of internet-based problem shopping behaviour: The concept of online shopping addiction and its proposed predictors. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 3(2), 83-89. [CrossRef]

- Rosenman, R. H., Friedman, M., Straus, R., Wurm, M., Jenkins, C. D., & Messınger, H. B. (1966). Coronary heart disease in the Western Collaborative Group study: A follow-up experience of two years. Journal of American Medical Association, 195(2), 86-92. [CrossRef]

- Rozgonjuk, D., Sindermann, C., Elhai, J. D., & Montag, C. (2021). Individual differences in Fear of Missing Out (FoMO): Age, gender, and the Big Five personality trait domains, facets, and items. Personality and Individual Differences, 171, 110546. [CrossRef]

- Saygılı, M., & Sütütemiz, N. (2017). Tüketicilerin alışveriş tarzına göre online alışverişin karşılaştırmalı analizi [Comparative analysis of online shopping according to consumers shopping style]. Researcher: Social Science Studies, 5(9), 230-243.

- Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H., & Müller, H. (2003). Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of Psychological Research Online, 8(2), 23-74.

- similarweb. (2023a, Nisan 1). Mart 2023 tarihinde en çok ziyaret edilen e-ticaret ve alışveriş web siteleri sıralama analizi [Ranking analysis of the most visited e-commerce and shopping websites in March 2023]. https://www.similarweb.com/tr/top-websites/e-commerce-and-shopping/.

- similarweb. (2023b, Nisan 1). Türkiye genelinde mart 2023 tarihli en popüler e-ticaret ve alışveriş web siteleri sıralama analizi [Ranking analysis of the most popular e-commerce and shopping websites in Turkey in March 2023]. https://www.similarweb.com/tr/top-websites/turkey/e-commerce-and-shopping/.

- Song, X., Zhang, X., Zhao, Y., & Song, S. (2017). Fearing of missing out (foMO) in mobil social media environment: Conceptual development and measurement scale. In iConferenre 2017 Proceedings, 733-738.

- Sönmez, U. (2019). Online alışverişe yönelik satın alma tarzlarının kişilik tipleri açısından incelenmesi: Sakarya ili örneği [Investigation of purchasing styles for online shopping in terms of personality traits: Case of Sakarya province]. (Unpublished master’s thesis). Sakarya Üniversitesi İşletme Enstitüsü.

- Sümer, N. (2000). Yapisal eşitlik modelleri: Temel kavramlar ve örnek uygulamalar [Structural equation modeling: Basic concepts and applications]. Türk Psikoloji Yaziları [Turkish Psychological Review], 3(6), 49-74.

- Sweller, J., Van Merriȅnboer, J. J. G., & Paas, F. G. W. C. (1998). Cognitive architecture and instructional design. Educational Psychology Review, 10(3), 251-296.

- Şahin, E., & Çavuş, B. F. (2020). Sosyal medya algısı ve FoMO’nun tüketici satın alma davranışına etkisinin belirlenmesine yönelik bir araştırma: Selçuk Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi örneği [A research about the fears of social media perception and FoMO on determining the effect of purchasing behavior of consumer: example of Selcuk University Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences]. Fırat Üniversitesi İİBF Uluslararası İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Dergisi [Firat University International Journal of Economics and Administrative Sciences], 4(1), 149-182.

- Taheer, F. (2023, April 14). 21 FOMO statistics: Understanding the fear of missing out. TrustPulse Marketing Blog. https://trustpulse.com/fomo-statistics/.

- Tandon, A., Dhir, A., Almugren, I., AlNemer, G. N., & Mäntymäki, M. (2021). Fear of missing out (FoMO) among social media users: A systematic literature review, synthesis and framework for future research. Internet Research, 31(3), 782-821. [CrossRef]

- Turkish Statistical Institute (TÜİK). (2022). Survey on Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Usage in Households and by Individuals, 2022. https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Survey-on-Information-and-Communication-Technology-(ICT)-Usage-in-Households-and-by-Individuals-2022-45587.

- Üster, Z. (2014). Elektronik ortamda alışveriş yapan tüketicilerin kontrolsüz satın alma eğilimlerinin incelenmesi: İnteraktif bir uygulama [An investigation of impulsive buying tendencies of shoppers in electronic environment]. Business & Management Studies: An International Journal. 2(2), 168-187. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. (2021). An empirical analysis of psychological factors based on EEG characteristics of online shopping addiction in e-commerce. Journal of Organizational and End User Computing, 33(6), 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, T., İkiz, G., & Avcı, F. M. (2022). Çevrimiçi alışveriş bağımlığı ölçeğinin Türkçe psikometrik özelliklerinin incelenmesi [Psychometric properties of Turkish online shopping addiction scale]. Bağımlılık Dergisi [Journal of Dependence], 23(2), 205-215. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., Jiménez, F. R., & Cicala, J. E. (2020). Fear of missing out scale: A self-concept perspective. Psychology & Marketing, 37(11), 1619-1634. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H., Tian, W., & Xin, T. (2017). The development and validation of the online shopping addiction scale. Frontier Psychology, 8(735), 1-9. [CrossRef]

| Gender | f | % |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 300 | 61.5 |

| Male | 188 | 38.5 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 283 | 58.0 |

| Married | 198 | 40.6 |

| Other | 7 | 1.4 |

| Age | ||

| 20 years and under | 88 | 18.0 |

| 21-30 years | 190 | 38.9 |

| 31-40 years | 143 | 29.3 |

| 41-50 years | 57 | 11.7 |

| 51 years and older | 10 | 2.0 |

| Household monthly total income status | ||

| Less than 10000 TL | 125 | 25.6 |

| Between 10001-20000 TL | 172 | 35.2 |

| Between 20001-30000 TL | 99 | 20.3 |

| Between 30001-40000 TL | 45 | 9.2 |

| Between 40001-50000 TL | 25 | 5.1 |

| More than 50001 TL | 22 | 4.5 |

| Number of shopping per month | ||

| 3 and less | 282 | 57.8 |

| Between 4-6 | 151 | 30.9 |

| Between 7-10 | 32 | 6.6 |

| Between 11-14 | 9 | 1.8 |

| more than 15 | 14 | 2.9 |

| Education status | ||

| Secondary school graduate | 2 | 0.4 |

| High school graduate | 111 | 22.7 |

| University student | 80 | 16.4 |

| Graduated from a Universty | 199 | 40.8 |

| Master's/PhD graduate | 96 | 19.7 |

| Online shopping preference | ||

| I prefer to do it from websites | 34 | 7.0 |

| I prefer to do it from mobile apps | 143 | 29.3 |

| I use both (web and mobile) | 311 | 63.7 |

| Daily internet usage time (including social media usage) | ||

| Less than 1 hour | 24 | 4.9 |

| 1-3 hours | 170 | 34.8 |

| 3-5 hours | 175 | 35.9 |

| More than 5 hours | 119 | 24.4 |

| Total | 488 | 100.0 |

| Frequency | Percentage in the number of participants | Percentage of total number of answers | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amazon | 120 | 24.59 | 9.55 |

| Alibaba | 20 | 4.10 | 1.59 |

| Hepsiburada | 309 | 63.32 | 24.58 |

| N11 | 145 | 29.71 | 11.54 |

| Trendyol | 464 | 95.08 | 36.91 |

| Ebay | 7 | 1.43 | 0.56 |

| Websites with physical store | 151 | 30.94 | 12.01 |

| Other | 41 | 8.40 | 3.26 |

| TOTAL | 1257 |

| Frequency | Percentage in the number of participants | Percentage of total number of answers | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food Market | 140 | 28,69 | 7,49 |

| Non-food market | 94 | 19,26 | 5,03 |

| Technology (Phone, Computer…) | 226 | 46,31 | 12,09 |

| Household goods/furniture/white… | 161 | 32,99 | 8,61 |

| DIY market/Hand tools | 91 | 18,65 | 4,87 |

| All kinds of spare parts | 65 | 13,32 | 3,48 |

| Clothes | 425 | 87,09 | 22,74 |

| Health | 72 | 14,75 | 3,85 |

| Education | 282 | 57,79 | 15,09 |

| Personal care | 304 | 62,30 | 16,27 |

| Other | 9 | 1,84 | 0,48 |

| Total | 1869 |

| B1 | B2 | S.E. | C.R. | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal FoMO | <--- | Personality type | -0,119 | -0,408 | 0,137 | -2,967 | 0,003 |

| Cognitive load for paying | <--- | Personal FoMO | 0,118 | 0,156 | 0,062 | 2,514 | 0,012 |

| Social FoMO | <--- | Number of shopping | -0,098 | -0,2 | 0,079 | -2,525 | 0,012 |

| Online Shopping Addiction | <--- | Personal FoMO | 0,283 | 0,054 | 0,013 | 4,205 | *** |

| Online Shopping Addiction | <--- | Social FoMO | 0,158 | 0,034 | 0,012 | 2,763 | 0,006 |

| Online Shopping Addiction | <--- | Cognitive load for paying | 0,128 | 0,018 | 0,007 | 2,752 | 0,006 |

| Online Shopping Addiction | <--- | Gender | 0,142 | 0,093 | 0,031 | 3,017 | 0,003 |

| Online Shopping Addiction | <--- | Number of shopping | 0,154 | 0,067 | 0,021 | 3,202 | 0,001 |

| Cognitive load for searching | <--- | Personal FoMO | 0,228 | 0,307 | 0,073 | 4,204 | *** |

| Cognitive load for purchase | <--- | Personal FoMO | 0,224 | 0,286 | 0,068 | 4,19 | *** |

| Cognitive load for searching | <--- | Social FoMO | -0,147 | -0,225 | 0,071 | -3,172 | 0,002 |

| Cognitive load for purchase | <--- | Social FoMO | -0,099 | -0,144 | 0,064 | -2,244 | 0,025 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).