1. Introduction

Choroid plexus papillomas (CPPs) are rare indolent neuroepithelial tumors that arise from the choroid plexus [

1]. CPPs usually exhibit high vascularity [

1]. Although the cornerstone of treatment for CPPs is safe surgical resection [

2,

3], there is an increased risk of serious blood loss during surgery, which complicates surgical resection and limits the ability to completely resect these tumors [

2]. Two-stage surgery should be considered based on intraoperative findings and characteristics of the tumor, such as tumor vascularity, operative blood loss, tumor adhesion, and surgical time. However, it has not yet been established how to leave the tumor for the next surgery when total tumor removal cannot be accomplished in the first surgery.

Surgical management of intracranial hypervascular tumors has always been a substantial challenge to neurosurgeons because of intractable intraoperative bleeding [

4]. Surgical strategies for hypervascular tumors have been reported, mainly with regard to arterial processing [

2]. Preserving of arterialized venous drainage in vascular tumors is considered to be important in brain tumor surgery, which has rarely been reported in the literature [

5].

We report a case of CPP in which resection considering venous drainage was important to avoid hemorrhagic complications during two-stage surgery. The current case suggests that it may be important to consider venous drainage during tumor resection, especially in cases of hypervascular tumors.

2. Case Presentation

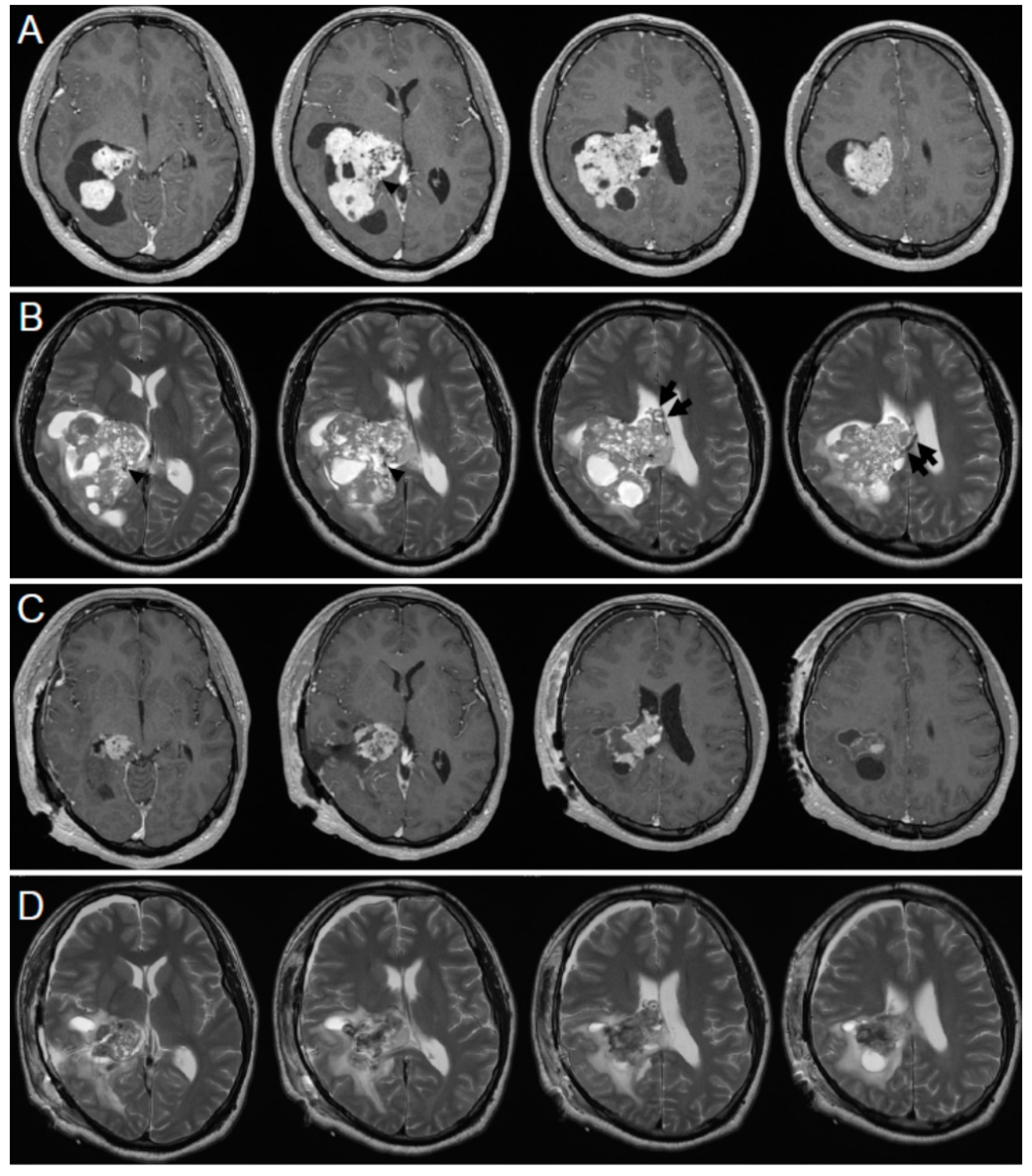

A 22-year-old healthy man presented with chief complaints of progressive headache and nausea that had persisted for two weeks. Neurological examination revealed no abnormal findings except for increased intracranial pressure signs. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a well-defined, brilliantly enhancing multicystic tumor extending from the inferior horn to the body of the right lateral ventricle (

Figure 1A). Marked peritumoral brain edema was observed in the right temporal and parietal lobes associated with a slight midline shift to the left, and the inferior horn of the right lateral ventricle was entrapped (

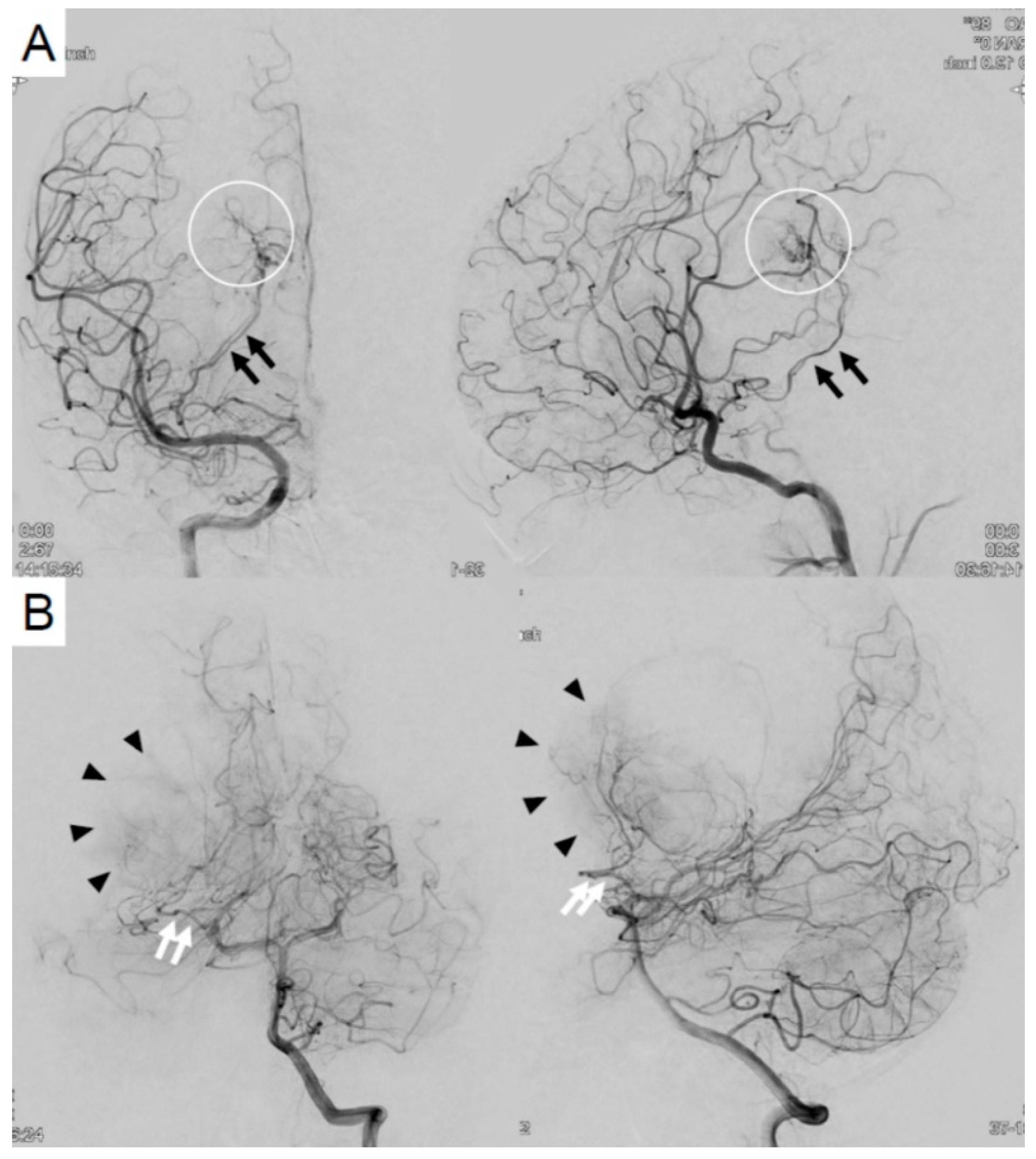

Figure 1B). Cerebral angiograms revealed that the tumor was fed by the anterior and lateral posterior choroidal arteries (

Figure 2). Preoperative endovascular feeder embolization using coils was performed in the anterior choroidal artery, and significant flow reduction was achieved. Tumor removal was planned. Under general anesthesia, right temporal craniotomy was performed. A 2-cm cortical incision in the middle temporal gyrus and a trajectory into the inferior horn of the lateral ventricle were made. A reddish tumor was observed in the ventricle. The lateral part of the tumor was resected and dissected from the ventricles. It was difficult to control the bleeding from the debulked tumor; therefore, removal of the medial part of the tumor was considered risky. The surgery was terminated because of severe blood loss (1732 mL). Large draining veins running in the tumor were not coagulated and preserved because they were red veins and were suspected as important drainage routes of the bloodstream of the tumor. MRI performed 5 days after the surgery showed a residual tumor with less enhancement, suggesting that the blood supply to the tumor was reduced (

Figure 1C, D).

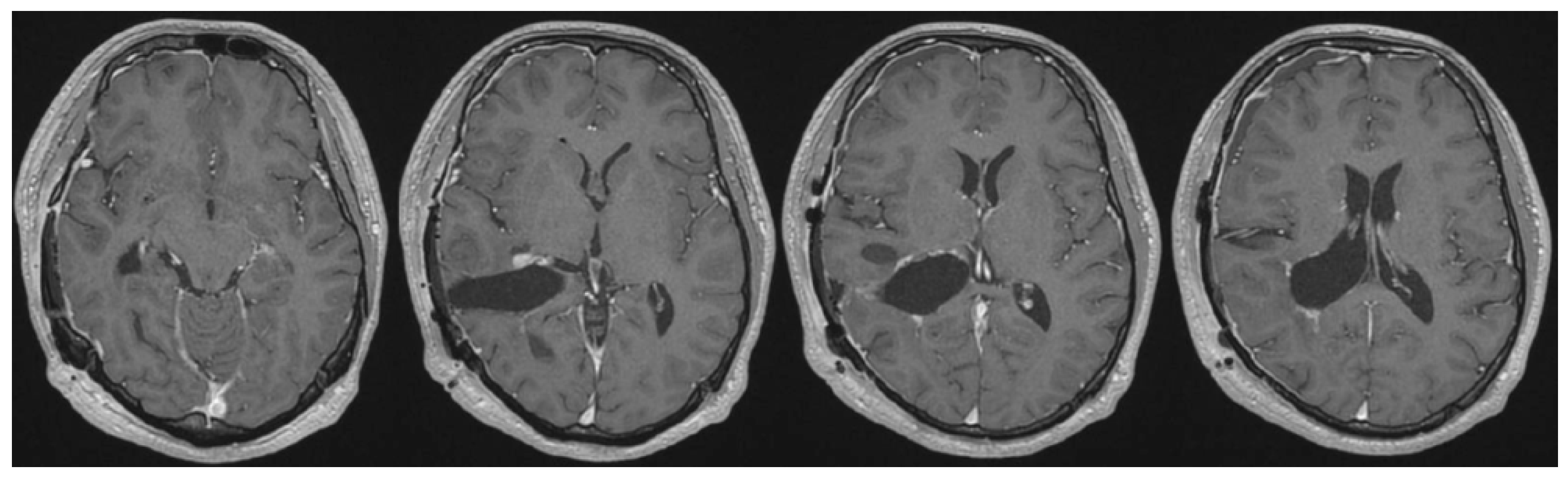

The second surgery was performed after 1 week using the same approach. The residual tumor was yellowish and not vascularized compared to the appearance of the tumor during the first surgery. The draining red veins preserved in the first surgery changed to a normal venous color (

Figure 3). The tumor was gross totally resected, with a total blood loss of 325 mL. Postoperative MRI showed that the tumor had been almost completely removed (

Figure 4). The patient tolerated the treatment well, and his intracranial pressure signs improved.

The pathological diagnosis was Grade I CPP based on the World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system [

6].

The patient was discharged without sequelae. There was no recurrence of the tumor during the 3-year follow-up.

3. Discussion

Surgical strategies for hypervascular tumors are often reported with regard to arterial processing (e.g., preoperative endovascular feeder embolization) [

2,

7]. However, only a few studies have focused on venous drainage [

5].

Choroid plexus tumors are usually highly vascularized, and intraoperative hemorrhage is a serious risk, especially in pediatric patients [

3]. These tumors develop in the ventricles; therefore, tumor-related hemorrhage can directly induce intraventricular hemorrhage, which is associated with high mortality and morbidity [

8]. It is important to prevent tumor-related, intraoperative, and postoperative hemorrhages when manipulating CPPs.

In this case, CPP was considered a hypervascular tumor on preoperative imaging. In terms of arterial processing, preoperative endovascular feeder embolization of the right anterior choroidal artery was performed. Although it may have been difficult to deal with the blood supply from the posterior choroidal feeders, we chose the middle temporal gyrus approach because of the location of the tumor and the ease of approaching the lesion.

Because of the arteriovenous malformation-like nature of hypervascular tumors, loss of venous drainage would be considered to increase the risk of intratumoral hemorrhage [

5]. To prevent postoperative hemorrhage related to disruption of venous drainage, venous drainage of the tumor should be considered and preserved when the tumor cannot be completely removed.

Particularly, the red vein is expected to be the primary drainage pathway for the tumor, reflecting the abundant feeder blood flow to the tumor and high number of arteriovenous shunts. In the present case, intentional preservation of the red vein may have contributed to venous drainage, preventing postoperative hemorrhage caused by venous disruption of the tumor.

In this case, the red vein observed in the first surgery changed to a normal coloration in the second surgery (

Figure 3). The color tone did not normalize during the first surgery; however, this was confirmed in the second surgery after 1 week. It is suggested that hemodynamic changes in the tumor take a few days. Yamakami et al. and LeMay et al. found that tumor blood flow was reduced after internal decompression [

7,

9] In the present case, the tumor tissue obtained from the first and second surgeries showed no differences in pathological examination. We speculated that preoperative feeder embolization and partial tumor resection may have resulted in a reduction in blood flow, leading to reduced bleeding in the second surgery. The mechanism of alteration of the blood supply to the residual tumor remains unknown. Therefore, further studies are necessary to elucidate the alterations in the blood supply and venous drainage of hypervascular tumors.

Postoperative hemorrhage can be classified as arterial-and/or venous-related hemorrhage. Generally, blood pressure control can prevent arterial-related postoperative bleeding; however, it is difficult to prevent venous-related hemorrhage from residual tumors. We speculated that the partial removal of the tumors, especially hypervascular tumors, may itself be considered a risk factor for postoperative venous-related bleeding. Postoperative venous-related hemorrhage related to the residual tumor can be caused by hemodynamic changes, especially a decrease in drainage pathways. Therefore, it is important to preserve venous drainage to prevent postoperative venous-related hemorrhage when surgeons choose to leave the tumor during surgical removal.

In the present case, two-stage surgery was successfully performed for a highly vascularized CPP without any complications. To prevent postoperative complications, especially postoperative hemorrhage associated with residual tumor, a minute preoperative evaluation of the tumor, not only arterial but also venous hemodynamics of the tumor, is required. Furthermore, it is important to orient intraoperative findings considering tumor vascularity, intraoperative bleeding, and venous drainage of the tumor when it is left.

4. Conclusions

It is important to prevent both intraoperative and postoperative tumor-related hemorrhage when manipulating CPPs. Preservation of venous drainage of the tumor is important to prevent postoperative venous-related hemorrhage when total removal of the tumor is abandoned. Intentional preservation of venous drainage, especially red veins, may contribute to venous drainage of a highly vascularized tumor, which prevents postoperative hemorrhage caused by venous disruption of the tumor.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, writing—original draft preparation, D.A. and K.K.; investigation, data curation, D.A., K.K., T.K., S.K., and K.S.; writing—review and editing, D.A. and K.K.; supervision, T.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient and his parents to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Safaee M, Clark AJ, Bloch O, Oh MC, Singh A, Auguste KI, Gupta N, McDermott MW, Aghi MK, Berger MS, Parsa AT. Surgical outcomes in choroid plexus papillomas: an institutional experience. J Neurooncol 2013, 113, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dash C, Moorthy S, Garg K, Singh PK, Kumar A, Gurjar H, Chandra PS, Kale SS. Management of Choroid Plexus Tumors in Infants and Young Children Up to 4 Years of Age: An Institutional Experience. World Neurosurg 2019, 121, e237–e245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safaee M, Oh MC, Bloch O, Sun MZ, Kaur G, Auguste KI, Tihan T, Parsa AT. Choroid plexus papillomas: advances in molecular biology and understanding of tumorigenesis. Neuro Oncol 2013, 15, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li P, Tian Y, Song J, Yang Z, Zou X, Liu P, Zhu W, Chen L, Mao Y. Microsurgical intracranial hypervascular tumor resection immediately after endovascular embolization in a hybrid operative suite: A single-center experience. J Clin Neurosci 2021, 90, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rachinger J, Buslei R, Prell J, Strauss C. Solid haemangioblastomas of the CNS: a review of 17 consecutive cases. Neurosurg Rev 2009, 32, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P, Brat DJ, Cree IA, Figarella-Branger D, Hawkins C, Ng HK, Pfister SM, Reifenberger G, Soffietti R, von Deimling A, Ellison DW. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Neuro Oncol 2021, 23, 1231–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeMay DR, Sun JK, Fishback D, Locke GE, Giannotta SL. Hypervascular acoustic neuroma. Neurol Res 1998, 20, 748–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinson HE, Hanley DF, Ziai WC. Management of intraventricular hemorrhage. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2010, 10, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamakami I, Kobayashi E, Iwadate Y, Saeki N, Yamaura A. Hypervascular vestibular schwannomas. Surg Neurol 2002, 57, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).