Submitted:

22 June 2023

Posted:

23 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Study area

Type of study

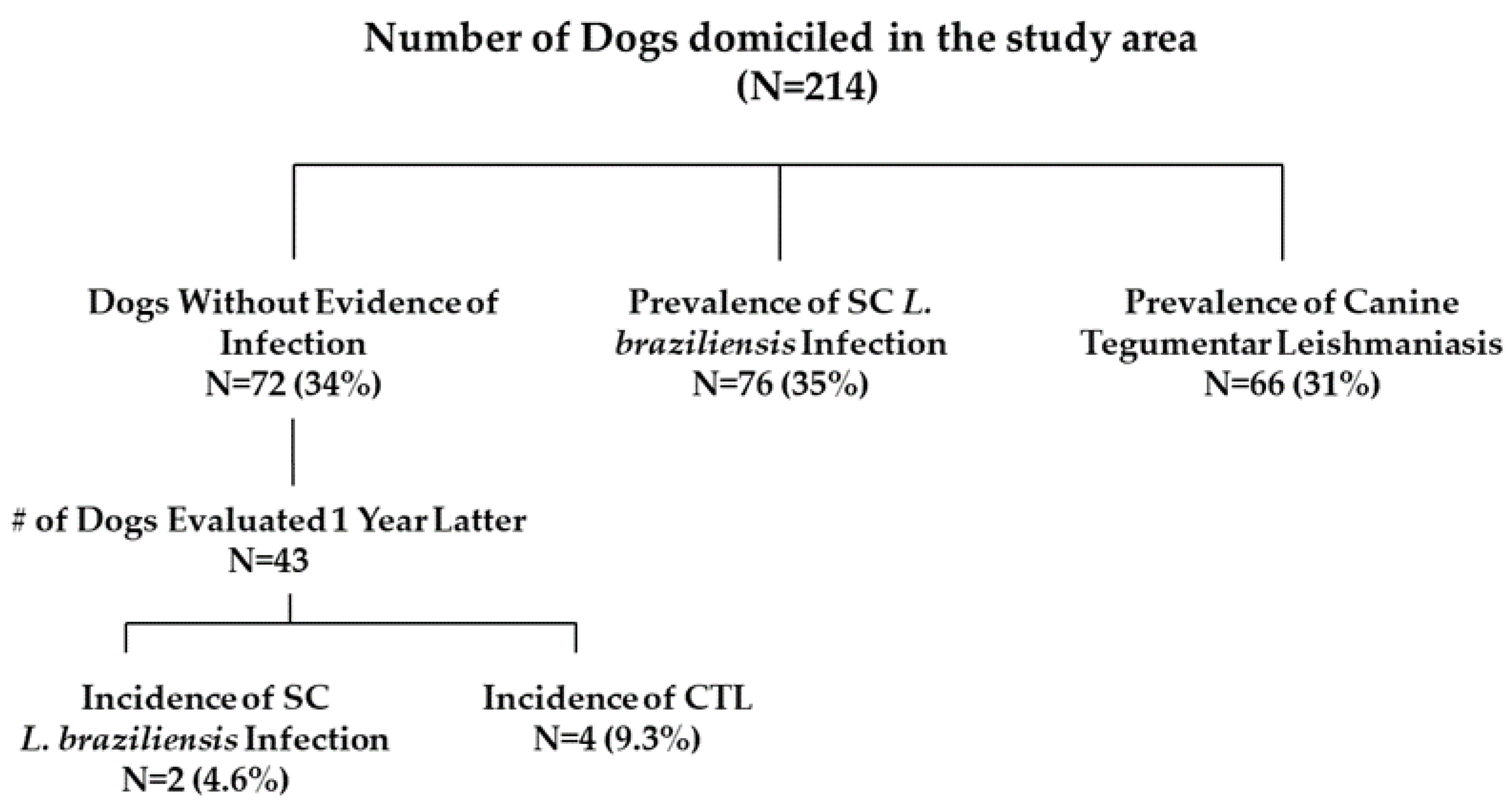

Study design for the first objective

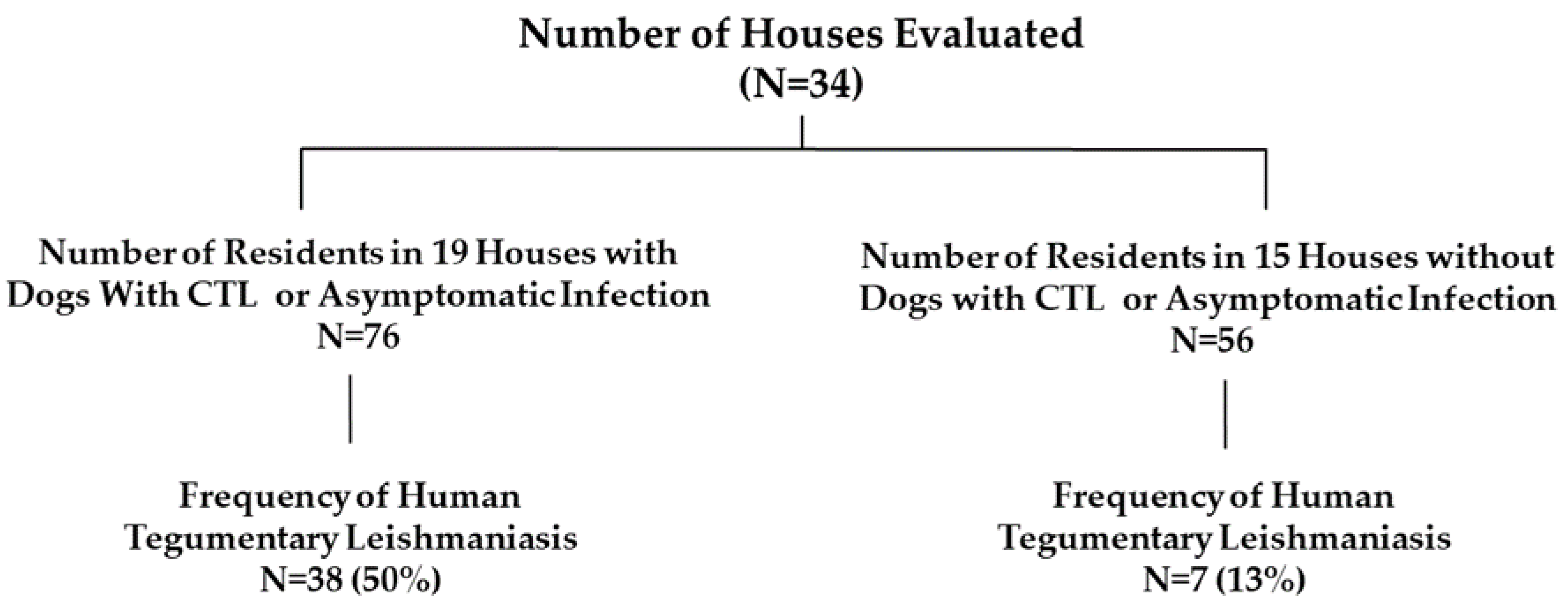

Study design for the second objective:

Diagnosis of SC Canine L. braziliensis Infection, CTL, and human ATL:

PCR for identification of Leishmania DNA

Soluble Leishmania Antigen (SLA), Serologic Test and Histopathology

Statistical analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Manual de Vigilâcia da Leishmaniose Tegumentar Americana / Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. 2. ed. Brasília: Editora do Ministério da Saúde, 2007. 180 p. (Serie A. Normas e Manuais Técnicos).

- Thomaz-Soccol, V.; Lanotte, G.; Rioux, J.A.; Pratlong, F.; Martini-Dumas, A.; Serres, E. Phylogenetic taxonomy of New World Leishmania. Ann Parasitol Hum Comp. 1993, 68, 104–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedoya-Pacheco, S.J.; Pimentel, M.I.F.; Conceição-Silva, F.; Araujo-Melo, M.H.; Marzochi, M.C.A.; Valete-Rosalino, C.M.; Schubach, A.O. Endemic Tegumentary Leishmaniasis in Brazil: Correlation between Level of Endemicity and Number of Cases of Mucosal Disease. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2011, 84, 901–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madeira, M.M.F.; Uchôa, C.M.; Leal, C.A.; Macedo Silva, R.M.; Duarte, R.; et al. Leishmania (Viannia) Braziliensis in naturally infected dogs. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2003, 36, 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Vigilância Epidemiológica. Manual de vigilância e controle da leishmaniose visceral / Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde, Departamento de Vigilância Epidemiológica. – Brasília: Editora do Ministério da Saúde, 2006.

- Varjão, B.M.; de Pinho, F.A.; Solcà, M.d.S.; Silvestre, R.; Fujimori, M.; Goto, H.; Varjão, N.M.; Dias, R.C.; Barrouin-Melo, S.M. Spatial distribution of canine Leishmania infantum infection in a municipality with endemic human leishmaniasis in Eastern Bahia, Brazil. 2021, 30, e022620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jr, G.G.; Teva, A.; Dos-Santos, C.B.; Santos, F.N.; Pinto, I.D.-S.; Fux, B.; Leite, G.R.; Falqueto, A. Field trial of efficacy of the Leish-tec® vaccine against canine leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania infantum in an endemic area with high transmission rates. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0185438–e0185438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duthie, M.S.; Raman, V.S.; Piazza, F.M.; Reed, S.G. The development and clinical evaluation of second-generation leishmaniasis vaccines. Vaccine 2012, 30, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reguera, R.M.; Morán, M.; Pérez-Pertejo, Y.; García-Estrada, C.; Balaña-Fouce, R. Current status on prevention and treatment of canine leishmaniasis. Veter- Parasitol. 2016, 227, 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotrina, J.F.; Iniesta, V.; Monroy, I.; Baz, V.; Hugnet, C.; Marañon, F.; Fabra, M.; Gómez-Nieto, L.C.; Alonso, C. A large-scale field randomized trial demonstrates safety and efficacy of the vaccine LetiFend® against canine leishmaniosis. Vaccine 2018, 36, 1972–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, G.P.L.; Sanavria, A.; Marzochi, M.C.d.A.; dos Santos, E.G.O.B.; Silva, V.L.; Pacheco, R.d.S.; Mouta-Confort, E.; Espíndola, C.B.; de Souza, M.B.; Ponte, C.S.; et al. Prevalência da infecção canina em áreas endêmicas de leishmaniose tegumentar americana, do município de Paracambi, Estado do Rio de Janeiro, no período entre 1992 e 1993. Rev. da Soc. Bras. de Med. Trop. 2005, 38, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago, J.; Silva, J.A.; Borja, L.; Fraga, D.B.M.; Schriefer, A.; Arruda, S.; Lago, E.; Carvalho, E.M.; Bacellar, O. Clinical and histopathologic features of canine tegumentary leishmaniasis and the molecular characterization of Leishmania braziliensis in dogs. PLOS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, J.C.; Reis, E.; Schriefer, A.; Gonçalves, M.; Reis, M.G.; Carvalho, L.; Fernandes, O.; Barral-Netto, M.; Barral, A. Frequency of infection of Lutzomyia phlebotomines with Leishmania braziliensis in a Brazilian endemic area as assessed by pinpoint capture and polymerase chain reaction. . 2002, 97, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel, E.F.; Lainson, R.; Carvalho, B.M.; Costa, S.M.; Shaw, J.J. Sand Fly Vectors of American Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Brazil. 2018, 341–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C.C.; Lacerda, H.G.; Martins, D.R.; Barbosa, J.; Monteiro, G.R.; Queiroz, J.W.; Sousa, J.M.; Ximenes, M.F.; Jeronimo, S.M. Changing epidemiology of American cutaneous leishmaniasis (ACL) in Brazil: a disease of the urban–rural interface. Acta Trop. 2004, 90, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marquez, E.d.S.; de Castro, E.A.; Nabut, L.B.; da Costa-Ribeiro, M.C.V.; Araújo, L.D.C.T.; Poubel, S.B.; Gonçalves, A.L.; Cruz, M.F.R.; Trad, A.P.M.E.d.S.; Dias, R.A.F.; et al. Cutaneous leishmaniosis in naturally infected dogs in Paraná, Brazil, and the epidemiological implications of Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis detection in internal organs and intact skin. Veter- Parasitol. 2017, 243, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, E.A.; Thomaz-Soccol, V.; Augur, C.; Luz, E. Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis: Epidemiology of canine cutaneous leishmaniasis in the State of Paraná (Brazil). Exp. Parasitol. 2007, 117, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weirather, J.L.; Jeronimo, S.M.B.; Gautam, S.; Sundar, S.; Kang, M.; Kurtz, M.A.; Haque, R.; Schriefer, A.; Talhari, S.; Carvalho, E.M.; et al. Serial Quantitative PCR Assay for Detection, Species Discrimination, and Quantification of Leishmania spp. in Human Samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011, 49, 3892–3904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, S.G.; Teixeira, R.; Badaró, R.; Carvalho, E.M.; Jr. , W.D.J.; Masur, H.; Jones, T.C.; Lorenco, R.; Lisboa, A. Selection of a Skin Test Antigen for American Visceral Leishmaniasis *. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1986, 35, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos-Santos, W.; Jesus, E.; Paranhos-Silva, M.; Pereira, A.; Santos, J.; Baleeiro, C.; Nascimento, E.; Moreira, E.; Oliveira, G.; Pontes-De-Carvalho, L. Associations among immunological, parasitological and clinical parameters in canine visceral leishmaniasis: Emaciation, spleen parasitism, specific antibodies and leishmanin skin test reaction. Veter- Immunol. Immunopathol. 2008, 123, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baleeiro, C.O.; Paranhos-Silva, M.; dos Santos, J.C.; Oliveira, G.G.; Nascimento, E.G.; de Carvalho, L.P.; Dos-Santos, W.L. Montenegro's skin reactions and antibodies against different Leishmania species in dogs from a visceral leishmaniosis endemic area. Veter- Parasitol. 2006, 139, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, A.; Carvalho, L.P.; Costa, R.; Pita, M.S.; Cardoso, T.M.; Machado, P.R.; Carvalho, E.M.; Arruda, S.; Carvalho, A.M. Anti-Leishmania IgG is a marker of disseminated leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania braziliensis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 106, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasani, F.; Javanbakht, J.; Samani, R.; Shirani, D. Canine cutaneous leishmaniasis. J. Parasit. Dis. 2014, 40, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzochi, M.C.d.A.; Fagundes, A.; de Andrade, M.V.; de Souza, M.B.; Madeira, M.d.F.; Mouta-Confort, E.; Schubach, A.d.O.; Marzochi, K.B.F. Visceral leishmaniasis in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: eco-epidemiological aspects and control. Rev. da Soc. Bras. de Med. Trop. 2009, 42, 570–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, T.C.; Johnson, W.D.; Barretto, A.C.; Lago, E.; Badaro, R.; Cerf, B.; Reed, S.G.; Netto, E.M.; Tada, M.S.; Franca, F.; et al. Epidemiology of American Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Due to Leishmania braziliensis brasiliensis. J. Infect. Dis. 1987, 156, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jirmanus, L.; Glesby, M.J.; Machado, P.R.; Carvalho, E.M.; Lago, E.; Rosa, M.E.; Guimarães, L.H. Epidemiological and Clinical Changes in American Tegumentary Leishmaniasis in an Area of Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis Transmission Over a 20-Year Period. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2012, 86, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, E.D.; DE Carvalho, L.P.; Sreenivasan, M.; Lopes, N.L.; Barreto, R.B.; DE Souza, V.M.M. PERIDOMESTIC RISK FACTORS FOR CANINE LEISHMANIASIS IN URBAN DWELLINGS: NEW FINDINGS FROM A PROSPECTIVE STUDY IN BRAZIL. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2003, 69, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, K.; Batista, Z.; Dias, E.; Guerra, R.; Costa, A.; Oliveira, A.; Calabrese, K.; Cardoso, F.; Souza, C.; Vale, T.Z.D.; et al. Canine visceral leishmaniasis in São José de Ribamar, Maranhão State, Brazil. Veter- Parasitol. 2005, 131, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solcà, M.d.S.; Arruda, M.R.; Leite, B.M.M.; Mota, T.F.; Rebouças, M.F.; de Jesus, M.S.; Amorim, L.D.A.F.; Borges, V.M.; Valenzuela, J.; Kamhawi, S.; et al. Immune response dynamics and Lutzomyia longipalpis exposure characterize a biosignature of visceral leishmaniasis susceptibility in a canine cohort. PLOS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2021, 15, e0009137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suprien, C.; Rocha, P.N.; Teixeira, M.; Carvalho, L.P.; Guimarães, L.H.; Bonvoisin, T.; Machado, P.R.L.; Carvalho, E.M. Clinical Presentation and Response to Therapy in Children with Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 102, 777–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, J.A.d.O.; Ribeiro, J.A.S.; Coelho, L.I.d.A.R.d.C.; Barbosa, M.d.G.V.; Paes, M.G. Epidemiologia da leishmaniose tegumentar na Comunidade São João, Manaus, Amazonas, Brasil. 2006, 22, 2319–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, L.H.; Machado, P.R.L.; Lago, E.L.; Morgan, D.J.; Schriefer, A.; Bacellar, O; Carvalho, E. Atypical manifestations of tegumentary leishmaniasis in a transmission area of Leishmania braziliensis in the state of Bahia, Brazil. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2009, 103, 712–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badaro, R.; Jones, T.C.; Lorenco, R.; Cerf, B.J.; Sampaio, D.; Carvalho, E.M.; Rocha, H.; Teixeira, R.; Johnson, W.D. A Prospective Study of Visceral Leishmaniasis in an Endemic Area of Brazil. J. Infect. Dis. 1986, 154, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeronimo, S.M.; Oliveira, R.M.; Mackay, S.; Costa, R.M.; Sweet, J.; Nascimento, E.T.; Luz, K.G.; Fernandes, M.Z.; Jernigan, J.; Pearson, R.D. An urban outbreak of visceral leishmaniasis in Natal, Brazil. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1994, 88, 386–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, N.E.; Dixit, U.G.; Wilson, M.E.; Jeronimo, S.M.B.; Lima, I.D.; Batra-Sharma, H.; Nascimento, E.L.; Lockard, R.D.; Turcotte, E.A. Epidemiological and Experimental Evidence for Sex-Dependent Differences in the Outcome of Leishmania infantum Infection. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2018, 98, 142–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, P. Impaired macrophage leishmanicidal activity at cutaneous temperature. Parasite Immunol. 1985, 7, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, A.; Sousa, R.; Heine, C.; Cardoso, M.; Guimarães, L.H.; Machado, P.R.L.; Carvalho, E.M.; Riley, L.W.; Wilson, M.E.; Schriefer, A. Association between an Emerging Disseminated form of Leishmaniasis and Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis Strain Polymorphisms. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012, 50, 4028–4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas-Torres, F. The role of dogs as reservoirs of Leishmania parasites, with emphasis on Leishmania (Leishmania) infantum and Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis. Veter- Parasitol. 2007, 149, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, J.D.; Padilla, A.M.; Diosque, P.; Fernández, M.M.; Malchiodi, E.L.; Basombrío, M.A. Force of infection and evolution of lesions of canine tegumentary leishmaniasis in northwestern Argentina. . 2001, 96, 649–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barretto AC, Cuba CC, Vexenat JA, Rosa A C, Marsden PD, Magalhães AV. Características epidemiológicas da leishmaniose tegumentar americana em um a região endêmica do Estado da Bahia. II Leishmaniose canina. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical 1984, 17, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfante-Garrido, R.; Valdivia, O.; Torrealba, J.; García, M.T.; Garófalo, M.M.; Urdaneta, I.; et al. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in cats (Felis domesticus) caused by Leishmania (Leishmania) venezuelensis. Rev Científica FCV-LUZ 1996, 6, 187–190. [Google Scholar]

- Barretto, A.C.; Peterson, N.E.; Lago, E.; Rosa, A.C.; Braga, R.S.; Cuba, C.A.; Vexenat, J.A.; Marsden, P.D. Leishmania mexicana in Proechimys iheringi denigratus Moojen (Rodentia, Echimyidae) in a region endemic for American cutaneous leishmaniasis. Rev. da Soc. Bras. de Med. Trop. 1985, 18, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vexenat, J.A.; Barretto, A.C.; Rosa, A.d.C.O.; Sales, C.C.; Magalhães, A.V. Infecção natural de Equus asinus por Leishmania braziliensis braziliensis - Bahia, Brasil. 1986, 81, 237–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, F.; Wenceslau, A.; Albuquerque, G.; Munhoz, A.; Gross, E.; Carneiro, P.; Oliveira, H.; Rocha, J.; Santos, I.; Rezende, R. Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis in dogs in Brazil: epidemiology, co-infection, and clinical aspects. Genet. Mol. Res. 2015, 14, 12062–12073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite, B.M.M.; Solcà, M.d.S.; Santos, L.C.S.; Coelho, L.B.; Amorim, L.D.A.F.; Donato, L.E.; Passos, S.M.d.S.; de Almeida, A.O.; Veras, P.S.T.; Fraga, D.B.M. The mass use of deltamethrin collars to control and prevent canine visceral leishmaniasis: A field effectiveness study in a highly endemic area. PLOS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2018, 12, e0006496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saldanha, M.G.; Queiroz, A.; Machado, P.R.L.; de Carvalho, L.P.; Scott, P.; Filho, E.M.d.C.; Arruda, S. Characterization of the Histopathologic Features in Patients in the Early and Late Phases of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017, 96, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, E.B.; Marzochi, M.; Conceição, N.; Brito, C.; Barroso, J.; Pacheco, R. N-methylglucamine antimonate (Sbv+): intralesional canine tegumentary leishmaniasis therapy. Parasite 1998, 5, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travi, B.L.; Tabares, C.J.; Cadena, H. Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis infection in two Colombian dogs: a note on infectivity for sand flies and response to treatment. 2006, 26, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago, J.; Fraga, D.; Guimarães, L.H.; Lago, T.; Santos, Y.; Lago, E.; Werneck, G.L.; Bacellar, O.; Carvalho, E.M. Efficacy of intralesional meglumine antimoniate in the treatment of canine tegumentary leishmaniasis: A Randomized controlled trial. PLOS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2023, 17, e0011064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Canine Tegumentary Leishmaniasis | Canine Subclinical infection | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 66 | N = 76 | ||

| Age (years), mean, (SD) | 5 ± 3 | 4 ± 3 | 0.09 |

| % of Male | 52/66 (79%) | 42/76 (55%) | 0.03 |

| Duration of illness (days), IQ | 90 (30-210) | - | |

| Positive Serology | 66 (100%) | 76 (100%) | - |

| Positive PCR | 47 (71%) | 3 (3.9%) | 0.01 |

| Revaluation after 1 year | |||

| Active CL | 38 (57.6%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Dead or sacrified dogs | 13 (19.7%) | ||

| Self-healing CTL | 15 (22.7%) |

| (n) | |

|---|---|

| Population of the Village | 504 |

| Prevalence of human cutaneous leishmaniasis | 183 (36%) |

| Number of Dogs in the Village | 88 |

| Prevalence of dogs with SC L. braziliensis infection | 20 (22.7%) |

| Prevalence of canine tegumentary leishmaniasis | 13 (14.7%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).