1. Introduction

Behavioral geography, a field of study that examines the relationship between human behavior and the physical environment, offers insights into the influence of spiritual places on individual behavior. These places, including mosques, synagogues, churches, and shrines, have immense spiritual significance. Behavioral geography examines how people interact with these sacred places (Collins-Kreiner, 2020) and how the physical environment influences their behavior (Shinde, 2011). In addition, recent developments in behavioral geography have emphasized the influence of religious artwork and spatial design on emotional and spiritual experiences. Studies have shown that the placement of religious paintings can influence people’s movements and interpersonal relationships. In addition, architectural elements such as light, color, and sound have been studied for their ability to evoke feelings of awe and reverence (Buttimer, 2006). Therefore, behavioral geography provides a framework for understanding how people's behavior in spiritual places differs from their behavior in other settings (Ley, 2015). This includes behaviors such as speaking softly, walking slowly, and engaging in contemplative activities such as prayer or meditation.

Behavioral geography also explores the evolution of moral behavior over time and its variations across cultures and societies (Ley, 2015). Understanding the role of religion and spirituality in shaping human behavior and social dynamics is a critical aspect of this field of study. In this sense, the focus of this article is on the Hajj pilgrimage, which has immense spiritual significance as a central pillar of Islam, the second-largest religion in the world. By applying the principles of behavior geography, we aim to examine how the Hajj pilgrimage affects the emotional and spiritual experiences of its participants.

Examining the Hajj through the lens of behavioral geography is significant and valuable due to its status as one of the largest religious gatherings in the world, attracting millions of participants each year. This study seeks to gain deep insights into the factors that influence pilgrims’ behavior during the Hajj. These factors include spatial and environmental elements that influence movement, as well as social and cultural influences that underlie pilgrims’ motivations and intentions. By analyzing these factors, researchers can identify areas that can be improved to enhance the safety and comfort of pilgrimage. Given the limitations of empirical research that rely solely on questionnaires, this study adopts a concise and theoretical approach. The main focus is on the “Masjid al-Haram - the Grand Mosque” in the city of Makkah (or Mecca), Saudi Arabia, which serves as the central point of the Hajj pilgrimage (see

Figure 1). Key elements of the pilgrimage include the building of the Kaaba, special places of worship, and notable landmarks such as the Maqam Ibrahim Stone (Station ˙of Prophet Abraham peace be upon him), the Black Stone, and the Stone Throwing Location (see also

Appendix A,

Figure A2). In this article, we explore how these structures and features influence pilgrims’ moral understanding and behavior. Essentially, through the lens of behavioral geography, we explore the interaction between individuals and the physical environment of the Hajj and how it shapes their behavior. The spatial organization of the pilgrimage emerges as a crucial aspect to explore through behavioral geography approaches.

2. Theoretical Background

1) Hajj from a behavioral geography perspective

Behavioral geography encompasses several theoretical perspectives that help to understand the relationship between human behavior and the physical environment. One influential theory in this field is “the theory of place and human behavior” (Schneider, 1987), which posits that the characteristics and attributes of a place significantly influence the behavior, attitudes, and experiences of people in that environment (Gold, 2009). This theory emphasizes the influence of physical spaces and their spatial organization on people's actions, emotions, and social interactions. Applied to the Hajj pilgrimage, this theory provides a framework for understanding how the physical design, layout, and symbolic elements of pilgrimage sites influence pilgrims behavior and experiences. Within this theory, researchers often explore the concept of place attachment, which refers to the subjective perceptions, meanings, and emotional connections that individuals make with a particular place. In the context of the Hajj, the sanctity and spiritual significance attributed to pilgrimage sites such as the Masjid al-Haram and the Kaaba foster a strong sense of place that influences pilgrims’ behavior and attitudes (

Figure 1). Another relevant perspective is the analysis of behaviors as proposed by Roger Barker and his colleagues (1963)

1. This approach examines how the attitudes and beliefs of individuals influence their behavior in specific environments (Heft, 2001). By examining the behaviors of pilgrims during the Hajj, researchers can gain insight into the motivations, intentions, and moral orientations that govern their actions during the pilgrimage. This theoretical framework provides a nuanced understanding of the complex interplay between individuals’ attitudes, cultural and religious beliefs, and behaviors during the Hajj.

Furthermore, place attachment and behavioral theory align with the broader concept of place attachment, which examines the emotional and cognitive connections that people develop to specific places (Scannell & Gifford, 2010). Place attachment recognizes the importance of sociocultural and historical context in shaping people’s relationships with their surroundings (Hernández et al., 2020). So, examination of the Hajj pilgrimage through the lens of place attachment help to explore the emotional and psychological dimensions that contribute to pilgrims’ attachment to pilgrimage sites and their behavior within those sites.

Behavioral geography, drawing on theories of place and human behavior, conduct, and place attachment, provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the intricate relationship between human behavior, religious spaces, and the physical environment (Moulay et al., 2018). By analyzing the spatial organization, sensory stimuli, social interactions, and emotional connections within the Hajj pilgrimage, researchers can uncover the factors that influence pilgrims' behaviors, motivations, and experiences. These insights help improve infrastructure, crowd management, and services to ensure the safety, comfort, and spiritual fulfillment of millions of participants worldwide (Wahyudie et al., 2021). In addition, the interdisciplinary nature of behavioral geography facilitates collaboration among scholars from different disciplines and promotes a holistic exploration of the complex dynamics between the physical environment, social factors, and human behavior during the Hajj and similar spiritual gatherings (Inalhan et al., 2021).

2) Comparison: Hajj and Other Holy Places

In various religious traditions, there are sacred sites that have deep ritual significance. These sites serve as consecrated places with deep religious and spiritual significance and shape the behavior of those who embark on a pilgrimage. In this section, we will examine examples of religious behavior in other faiths, highlighting both the similarities and unique characteristics of these sacred places.

One notable example is the Western Wall, a sacred site in Jerusalem, Palestine that is revered in Judaism. It is considered the holiest site in Judaism and attracts pilgrims from around the world who gather there for worship and prayer (Winder, 2012). The behavior of visitors to the Wailing Wall is influenced by its historical and religious significance, as well as by the rituals and customs associated with the site. Similarly, St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, Italy, has immense significance for Catholics worldwide. As one of the most revered Catholic churches, it serves as the site for central religious ceremonies and events. Visitors to St. Peter's Basilica are guided by the deep religious and cultural significance it carries, as well as the customs and traditions upheld by the Catholic Church (Jasieńko, J., et al. (2021). Another sacred site worthy of mention is the Golden Temple in Amritsar, India, which holds prominent significance in Sikhism. It is considered the holiest site in Sikhism and is of great spiritual and cultural significance. The behavior of visitors to the Golden Temple is shaped by the teachings of Sikhism and the customs and traditions associated with the site (Tripathi et al., 2010). Bodh Gaya in the Indian state of Bihar is home to a site of great significance to Buddhists. It is believed to be the place where Buddha attained enlightenment. Bodh Gaya shapes the behavior of its visitors in accordance with Buddhist teachings and the customs and rituals associated with the site (Piramanayagam et al., 2020). At all of these sacred sites, visitor behavior is profoundly influenced by the cultural, religious, and historical significance they hold, as well as the customs, rituals, and traditions that have developed over time. These sites of religious practice occupy a central place in the spiritual lives of many people and are significant cultural and social landmarks (Devine-Wright & Clayton, 2010).

It is important to address ongoing debates and trends related to these sacred sites. One of these debates revolves around inclusivity and access, ensuring that these sites welcome people of all backgrounds and faiths to promote inclusivity and foster interfaith dialog. Efforts are underway to create more inclusive spaces and facilitate visits by people from diverse religious and cultural backgrounds (Stoyanov, 2016). Preservation of these sacred sites is another important trend. Preservation efforts are aimed at protecting the architectural, historical, and cultural heritage of these sites. Discussions revolve around finding a balance between preserving the authenticity and sacredness of these sites while ensuring their sustainable maintenance and preservation for future generations (Aulet et al., 2017).

Interfaith dialog is an important trend, with initiatives promoting dialog and cooperation among religious communities (Rofiqi & Haq, 2022). These efforts aim to promote understanding, tolerance, and cooperation among people of different faiths who visit these sites. Interfaith dialogs and events are organized to promote mutual respect, address common challenges, and create harmony. Given the significant influx of visitors, tourism management and sustainability become ongoing issues. It is a matter of finding a balance between the needs of visitors and the preservation of these sacred sites. Sustainable tourism practices, strategies to manage visitor flows, and infrastructure development are important areas of interest (Bartholomew, 2022). Technology is playing an increasingly important role in enhancing the visitor experience and managing these sites. Current trends include the use of digital platforms, mobile applications, and virtual reality to provide information, guidance, and interactive experiences to visitors. Technological advances are also being used to manage visitor flows, improve security measures, and preserve the authenticity of these sites (El-Shamandi Ahmed et al., 2023). These debates and trends underscore the evolving nature of these sacred sites and ongoing efforts to ensure their continued relevance, accessibility, and sustainable stewardship in the modern world.

3. Method

In this study, the focus was on Masjid al-Haram, a revered place for Muslims, to investigate its influence on visitor behavior. Due to current limitations in conducting interviews or using empirical methods, a qualitative analysis approach within the framework of the geography of ethics was used. To conduct the research, an extensive review of religious literature and online publications was undertaken. In addition, numerous “live” videos of the Hajj pilgrimage were carefully analyzed through the YouTube platform, particularly through the

www.haramainsharifain.com channel Hajj instructions were also thoroughly reviewed

2. Theoretical data were collected from behavior geography lectures and integrated for analysis under my professor’s guidance.

3 The study was primarily concerned with the spatial location of the Masjid al-Haram and the influence of cultural and religious beliefs on visitor behavior.

The results showed that the spatial layout of the Grand Mosque, particularly the design of the central courtyard (Mataf) and the presence of pillars, played an important role in shaping pilgrims' behavior during the Tawaf (circumambulation) ritual.

4 These elements facilitated the movement of large crowds, provided protection from the sun, and enhanced the spiritual significance of the ceremony.

Based on the video observations, it was clear that crowds and ambient noise had a critical impact on the Tawaf (circumambulation) experience. Moving through large crowds was challenging and it was difficult to maintain personal space, leading to feelings of anxiety. However, it was found that the background noise and overall atmosphere contributed to the spiritual value of the ceremony and enhanced the overall sense of devotion.

Cultural and religious beliefs were also found to have a major impact on pilgrims’ behavior during the circumambulation. These beliefs, rooted in the sanctity of the Kaaba as the House of God, evoked feelings of awe and reverence among pilgrims. Furthermore, we hypothesize that the concept of “Ummah”, which is a symbol of the unity of the Muslim community, strengthens the collective approach to Tawaf (circumambulation) and the sense of solidarity among pilgrims. Thus, the results of this study provide a comprehensive understanding of the factors that influence pilgrims' behavior during Tawaf (circumambulation). The spatial location of the Masjid al-Haram, environmental factors, cultural and religious beliefs, and social interactions all interact to shape pilgrims' behavior and experiences during this significant religious ritual.

4. Important Places during the Hajj

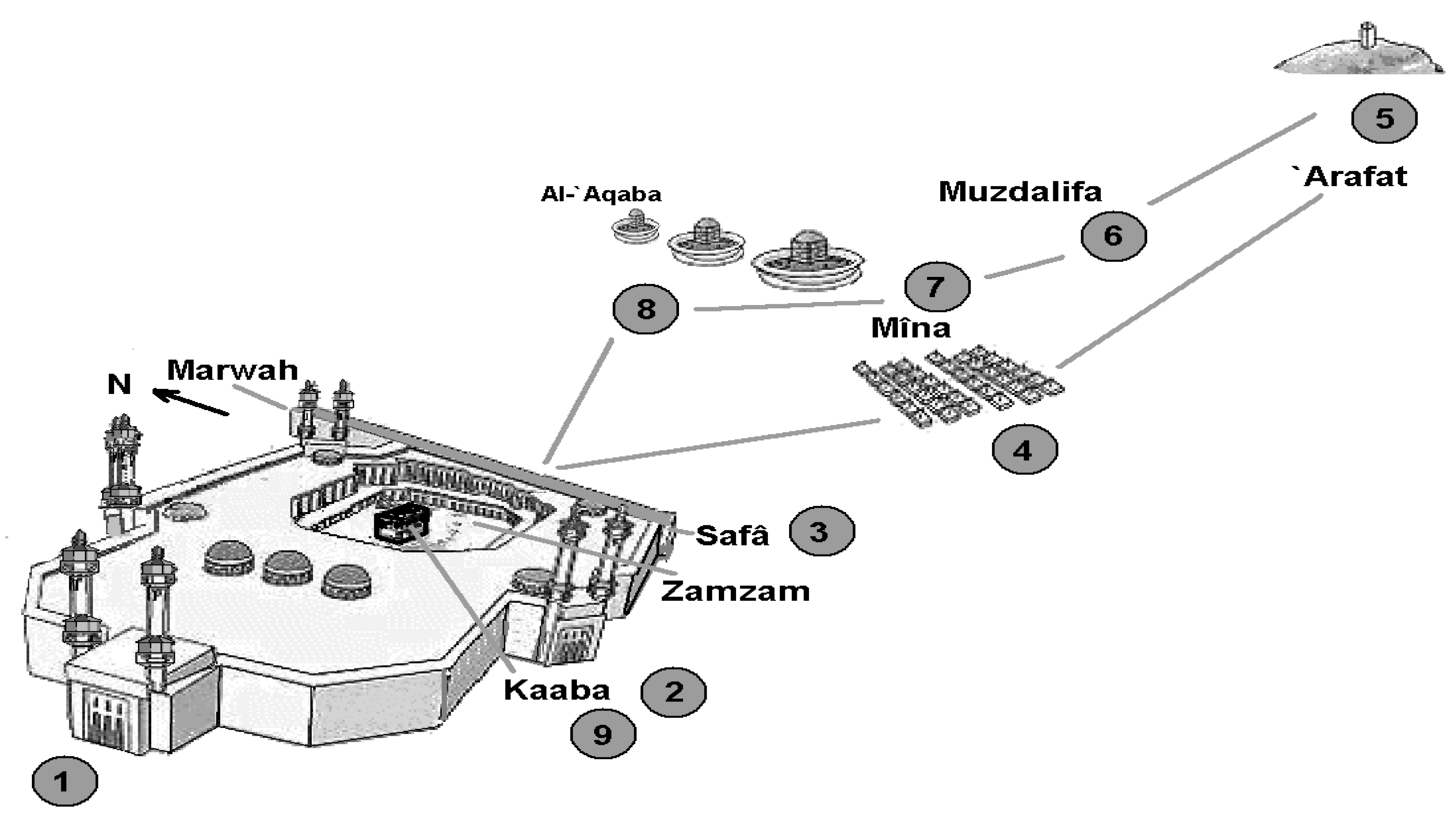

The Hajj pilgrimage is a multi-layered and complex event that encompasses a range of behaviors and practices, many of which are spatial in nature (see

Appendix A,

Figure A1). In this section, we will look at the main places that are of immense importance as “places of behavior” during the Hajj (Elgammal et al., 2023). The first of these places is the Kaaba, a structure known as the “House of God” according to Islamic teachings. Located in the center of the Masjid al-Haram, the Kaaba is a cube-shaped building about 15 meters high with sides 12 meters long and 10.5 meters wide.

5 The interior of the Kaaba is decorated with a marble and limestone floor about 2 meters above the ground where the Tawaf (circumambulation) ritual takes place. People circumbulate the Kaaba seven times (

Figure 3). The total area of Al-Haram Mosque, including the Kaaba, is 193,000 square meters and can accommodate 130,000 people at the same time. This holy site is the most sacred place in Islam and serves as the focal point of the Hajj pilgrimage (

Figure 2). As mentioned earlier, pilgrims circumambulate the Kaaba seven times as part of their Hajj journey (

www.www.haramainsharifain.com).

The second important site is the Valley of Mina

[M-ee-n-å:], located about 5 kilometers east of Makkah. Pilgrims spend the first night of the Hajj at the campsite in this valley, which has been nicknamed the “City of Tents” because of its more than 100,000 air-conditioned tents. With a capacity for up to 3 million people, Mina is the largest tent city in the world (see

Figure 5, number “8”). The next day pilgrims will go from Mina to Mount Arafat (see

Figure 5;

Appendix A,

Figure A1).

Mount Arafat, the third important site, is a hill about 20 kilometers east of Makkah. Mount Arafat rises to a height of about 70 meters (230 feet) and its highest point is at 454 meters (1490 feet). Mount Arafat is of immense importance as the place where Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) delivered his last sermon (

www.www.haramainsharifain.com). This place is an important pilgrimage site. As mentioned earlier, pilgrims spend the whole day on Mount Arafat to pray and contemplate (see

Figure 5, number “5”).

The fourth place of importance is the site of the Jamarat pillars. These three stone pillars, located in the Mina Valley, symbolize “Satan” in the Islamic tradition (see

Figure 5, numbers “6” and “7”). Pilgrims participate in the ritual of “stoning the devil” by throwing stones at these pillars. It is worth noting that this ritual recalls the actions of Prophet Abraham (peace be upon him), who stoned the devil (Satan, i.e., Lucifer in the Bible) to thwart his attempts to fulfill the divine command to sacrifice his son Ismail (i.e., Ishmael peace be upon him). The ritual requires a minimum of 49 pebbles to be thrown, with additional throws in case of misses (

Figure 5, number “8”). Some pilgrims choose to stay at Mina for another day, requiring another round of stoning each pillar seven times.

The fifth notable site is Muzdalifa, an open-air site about 9 kilometers southeast of the Mina Valley. At this site, pilgrims rest after completing the “stoning of the devil” ceremony. It should be noted that, the stones collected in Muzdalifa are used for the subsequent ritual of stoning the Devil (see

Figure 5, numbers “4” and “8”).

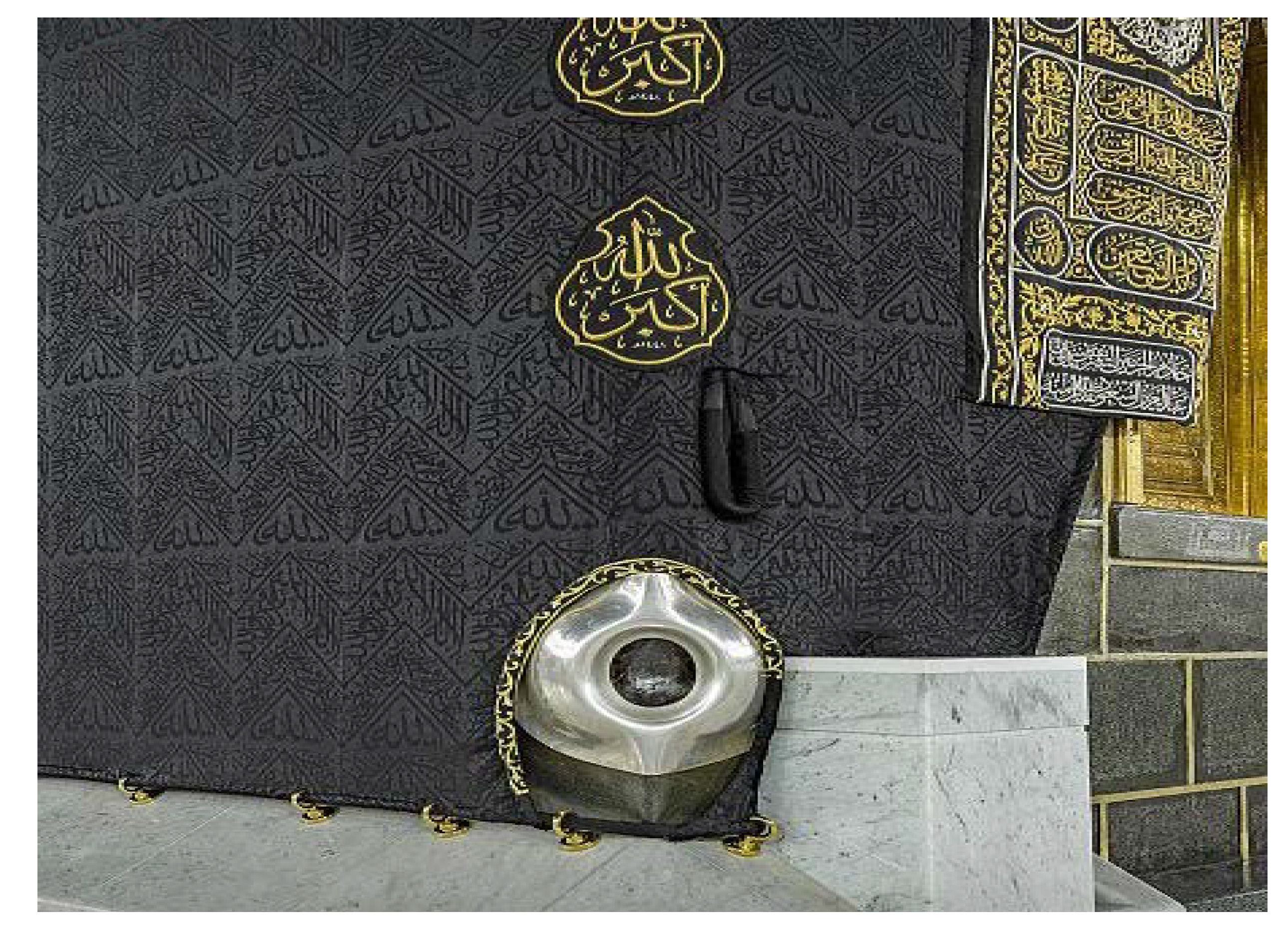

In addition, the Black Stone is an important feature of the Kaaba. Located in the eastern corner of the Kaaba building, the Black Stone is revered by Muslims as an Islamic relic that, according to Muslim tradition, dates back to the time of Adam and Eve. The stone is mounted in a silver frame and bears a resemblance to dark fragments polished by the touch of countless pilgrims. It measures 76 centimeters in length and 46 centimeters in width. Islamic tradition states that the stone descended from heaven to help Adam and Eve build an altar. It is also often associated with a meteorite. As part of the Tawaf (circumambulation) ritual during the Hajj, pilgrims kiss the Black Stone or make a gesture in its direction as they circumambulate the Kaaba. Although the Black Stone is honored in Islamic teachings, it has no divine significance (

Figure 4).

Another sacred object in the Masjid al-Haram is the Maqam Al-Ibrahim, also known as “The Station of Abraham”. It is a black and red stone with the footprints of the Prophet Abraham (peace be upon him). The stone is located in a glass dome, visible to pilgrims, and is surrounded by an elaborate golden cage decorated with intricate engravings. A curtain called

Sitara further embellishes the cage. The stone measures 8 inches in height, 14 inches in width, and 15 inches in length (see:

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

These examples illustrate several important sites that serve as central locations of activity during the Hajj pilgrimage. Each of these sites has a particular spatial and cultural significance in the context of the Hajj and profoundly shapes the behavior and practices of pilgrims. The objects in the Masjid al-Haram have immense symbolic value and play a crucial role in shaping pilgrims' behavior in performing the Tawaf (circumambulation) and other rituals. These objects are rooted in religious and cultural beliefs and have a significant impact on pilgrims’ behavior and overall experience (

Figure 5 and

Table 1).

5. Hajj—Place of Behavior

The Hajj pilgrimage has immense significance as a journey that encompasses various behavioral aspects. Examining the pilgrimage through the lens of behavioral geography offers insights into the personal motivations, social cohesion, cultural exchanges, and historical significance associated with the Hajj (

Table 2).

One important aspect is the pilgrims’ quest for “spiritual fulfillment”. Islamic teachings emphasize that the Hajj provides Muslims with the opportunity to deepen their faith and establish a deep connection to their spiritual roots. The performance of customs and traditions during Hajj serves to strengthen pilgrims' relationship with God and find spiritual enjoyment. This pursuit of spiritual fulfillment during the Hajj is consistent with the concept of “place-based spirituality” in behavioral geography, which highlights how people seek transcendent experiences and engage with sacred spaces to create a deeper connection with their faith.

The Hajj also promotes “social cohesion” by bringing together Muslims from diverse backgrounds around the world. Through their participation in the pilgrimage, pilgrims become part of a larger community of believers who share a common identity and goal. This sense of belonging to a community and solidarity strengthens social cohesion among Muslims. From a behavioral geography perspective, this phenomenon can be understood through the concept of “place-based identity formation”, which assumes that people develop a sense of identity and attachment to a place through their shared experiences and interactions with others. The Hajj pilgrimage serves as a powerful catalyst for the formation of collective identity and social cohesion among participating pilgrims.

“Cultural exchange” is another important aspect of the hajj pilgrimage. When Muslims from different cultures come together in Makkah, they could engage in intercultural exchange and share their experiences and traditions. The Hajj becomes a place where cultural boundaries are transcended, allowing for the exchange of ideas, practices, and perspectives. This is consistent with the principles of “behavioral diffusion” in geography, which emphasizes how cultural practices and knowledge spread through social interactions and exchanges. The Hajj pilgrimage serves as a platform for pilgrims to engage in cultural exchange and promotes mutual understanding and appreciation of diverse cultural backgrounds.

Finally, the Hajj is of “historical significance” as it has been a fundamental principle of Islam since the time of the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him).

Thus, by participating in the Hajj, Muslims reaffirm their commitment to this rich historical tradition and contribute to its continuation. The pilgrimage becomes a symbolic act of reverence and adherence to the teachings and practices of Islam. In the context of behavioral geography, this is consistent with the concept of “place-based memory and heritage”, which recognizes how places carry historical meanings and evoke collective memories. The Hajj pilgrimage represents a tangible and lived experience of Islamic history and reinforces the historical significance associated with the journey. So, viewing the Hajj pilgrimage from the perspective of behavioral geography highlights its multi-faceted nature. The pilgrimage encompasses spiritual fulfillment, social cohesion, cultural exchange, and historical significance. Understanding these behavioral aspects enhances our understanding of the various motivations and experiences of pilgrims during the Hajj, while also clarifying the role of place in shaping their behavior and interactions.

6. Discussion

The discussion of the influence of spatial conditions, environmental factors, cultural and religious beliefs, and social communication on pilgrims’ behavior during the Tawaf (circumambulation) of the Hajj pilgrimage is consistent with several theories of behavioral geography. Two relevant theories are “

behavioral attitudes” and “

place attachment” (

Table 3).

The first is behavioral theory. This theory, developed by Roger Barker and colleagues, focuses on how the physical and social environment influences human behavior. It recognizes that behavior is influenced not only by individual characteristics but also by the characteristics of the environment in which it occurs. In the context of the Tawaf (circumambulation) ritual, behavioral theory can be applied to understand how the spatial organization of the Masjid al-Haram, the presence of large crowds, the noise level, the physical design, and technology used in the mosque, and the social interactions among pilgrims all contribute to influencing individual behavior during Tawaf (circumambulation).

The second one is place attachment. Place attachment theory refers to the emotional and cognitive attachments that people develop to specific places. In the case of the Hajj pilgrimage, the Kaaba and the Masjid al-Haram have immense religious and cultural significance for Muslims worldwide. Belief in the holiness of the Kaaba, the sense of unity and community fostered by the pilgrimage, and the cultural and religious values associated with the Hajj all contribute to pilgrims developing strong attachments to the site. These bonds, in turn, shape their behavior during the Tawaf (circumambulation) and their overall experience of the pilgrimage. Thus, if we apply these theoretical frameworks to the field of behavioral geography, we can explore the intricacies of interdependencies between the physical milieu, social engagement, and individual behavioral patterns during the Tawaf (Circumambulation) ceremony and the broader context of the hajj pilgrimage. Also, these theories serve as a central foundation for understanding the underlying motivations, attitudes, and actions pilgrims exhibit during Tawaf (circumambulation) while illuminating the dynamic nature of their behavior in specific spatial contexts. To consolidate and substantiate these claims, the following table summarizes the above considerations.

7. Conclusions

The Hajj pilgrimage and the Tawaf (circumambulation) ritual at the Kaaba are thus complex phenomena involving a range of behaviors, rituals, and social interactions. The Kaaba itself is of immense spiritual significance to Muslims, and the objects within it, such as the Black Stone and the Ihram garments, are important elements of the pilgrimage (

Appendix A,

Figure A3). Behavioral geography provides a valuable framework for understanding the interplay between spatial location, social relations, cultural beliefs, and individual behavior during Tawaf (circumambulation). By examining the dynamics of the Hajj pilgrimage through the lens of behavioral geography, we have sought to gain insight into the factors that shape pilgrims' behavior and experiences. We hope that this understanding can help to improve the organization of the pilgrimage, enhance safety, and provide greater comfort and convenience to pilgrims. In addition, behavioral geography allows for an exploration of the cultural and social factors that influence pilgrims’ behavior, including the importance of social interactions, communication, and the role of cultural beliefs and traditions.

In addition, behavioral geography can help improve the overall experience of the Hajj pilgrimage by tailoring services and support to meet the diverse needs of different groups of pilgrims. By considering the spatial and environmental factors that affect pilgrims' behavior, as well as the cultural and social factors that underlie their motivations and intentions, pilgrimage organizers can create a more accessible, safe, and fulfilling experience for all participants. The Hajj pilgrimage and the Tawaf (circumambulation) at the Kaaba thus represent a unique and complex behavioral landscape that encompasses a variety of rituals, actions, and social relationships. Behavioral geography offers valuable insights into the ways in which spatial location, social interactions, cultural beliefs, and other factors shape pilgrims' behavior during the Hajj. By examining and analyzing pilgrims’ experiences, we can uncover patterns and themes that contribute to a deeper understanding of the Tawaf (circumambulation) ritual and the overall meaning of the hajj pilgrimage.

Appendix A

Figure A3.

“Ihram” clothing during the Hajj pilgrimage, Source:

www.makkah-madinah.accor.com.

Note: Men’s “Ihram” dress is made of two pieces of white fabric, without seams, hem, and buttons. During the Tawaf (circumambulation) ritual, there are certain guidelines for dress. The lower part, called “Izar” [

ee-zaa-r], is wrapped around the waist and covers the area from the navel to the feet. The upper part called the “Rida” [

r-ee-da`], should always cover the left shoulder. It is important that the right shoulder remains free during Tawaf (circumambulation). It is not permitted to wear underwear, socks, or other additional clothing, and it is recommended that the head not be covered. However, it is permitted to wear shoes that show the ankles and toes. “Ihram”, i.e., attire for women during ihram consists of a loose-fitting robe that covers the entire body. The robe may have seams and buttons, but it should not have any decorations or colors. It can be either white or black in color. It is important to keep the hands and face exposed while wearing the ihram dress. Additionally, women should wear shoes that fully cover the feet.

Figure A3.

“Ihram” clothing during the Hajj pilgrimage, Source:

www.makkah-madinah.accor.com.

Note: Men’s “Ihram” dress is made of two pieces of white fabric, without seams, hem, and buttons. During the Tawaf (circumambulation) ritual, there are certain guidelines for dress. The lower part, called “Izar” [

ee-zaa-r], is wrapped around the waist and covers the area from the navel to the feet. The upper part called the “Rida” [

r-ee-da`], should always cover the left shoulder. It is important that the right shoulder remains free during Tawaf (circumambulation). It is not permitted to wear underwear, socks, or other additional clothing, and it is recommended that the head not be covered. However, it is permitted to wear shoes that show the ankles and toes. “Ihram”, i.e., attire for women during ihram consists of a loose-fitting robe that covers the entire body. The robe may have seams and buttons, but it should not have any decorations or colors. It can be either white or black in color. It is important to keep the hands and face exposed while wearing the ihram dress. Additionally, women should wear shoes that fully cover the feet.

Notes

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

Online News Medium, the second largest source of digital media in Saudi Arabia, news and content hub related to the Two Holy Mosques. |

| 3 |

Department of Geography, Chonnam National University, Gwangju, South Korea, www.geo.jnu.ac.kr

|

| 4 |

Tawaf (circumambulation), an Arabic term, is used to describe a fundamental ritual of the pilgrimage where individuals walk in circles around the Kaaba in an anti-clockwise direction, known as “circumambulation”. |

| 5 |

Note: Hawting gives the height as 10 meters or 32 feet 10 inches. |

References

- Aulet, S. , et al., (2017). Monasteries and tourism: interpreting sacred landscape throughgastronomy. Revista Brasileira de Pesquisa em Turismo, 11, pp.175-196.

- Barker, R. G. (Ed.) . (1963). The stream of behavior: Explorations of its structure & content.Appleton-Century-Crofts. [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, E. P. (2022). In the world, yet not of the world. In In the World, Yet Not of the World.Fordham University Press.

- Buttimer, A. , (2006). Afterword: Reflections on Geography, Religion, and Belief Systems.Annals of the Association of American Geographers 96, no. 1, pp.197-202.

- Campbell, I. (1981). The New St. Peter's Basilica Or Temple?, Oxford University Press.

- Collins-Kreiner, N.; Kliot, N. Pilgrimage tourism in the Holy Land: The behavioural characteristics of Christian pilgrims. GeoJournal 2000, 50, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine-Wright, P.; Clayton, S. Introduction to the special issue: Place, identity and environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 267–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K.E.-S.; Ambika, A.; Belk, R. Augmented reality magic mirror in the service sector: experiential consumption and the self. J. Serv. Manag. 2022, 34, 56–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgammal, I.; Alhothali, G.T.; Sorrentino, A. Segmenting Umrah performers based on outcomes behaviors: a cluster analysis perspective. J. Islam. Mark. 2022, 14, 871–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, J. R. (2009). Behavioral geography. International encyclopedia of human geography, 1,pp.282-293.

- Heft, H. (2001). Ecological psychology in context: James Gibson, Roger Barker, and the legacy of William James's radical empiricism. Psychology Press.

- Hernández, B. , et al. ( 2020). Theoretical and methodological aspects of research on placeattachment. Place Attachment, 94–110.

- Inalhan, G. , et al. (2021). Place attachment theory. A handbook of theories on designing alignment between people and the office environment, pp.181-194.

- Jasieńko, J. , et al. (2021, June). Numerical analysis of historical masonry domes: A study ofSt. Peter’s Basilica dome. In Structures, Vol. 31, pp. 80-86, Elsevier.

- Ley, D. (2015). Behavioral geography and the philosophies of meaning. In Behavioral problemsin geography revisited, Routledge, pp.209-230.

- Moulay, A. , et al., (2018). Understanding the process of parks’ attachment: Interrelation betweenplace attachment, behavioural tendencies, and the use of public place. City, Culture and Society,14, pp.28-36.

- Olsen, D.H. Negotiating identity at religious sites: a management perspective. J. Heritage Tour. 2012, 7, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piramanayagam, S. , et al. (2020). Tourist’s motivation and behavioural intention to visit a religious Buddhist site: a case study of Bodhgaya. International journal of religious tourism andpilgrimage, 8(8), p.5.

- Rofiqi, M.A.; Haq, M.Z. Islamic Approaches in Multicultural and Interfaith Dialogue. Integritas Terbuka: Peace Interfaith Stud. 2022, 1, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B. THE PEOPLE MAKE THE PLACE. Pers. Psychol. 1987, 40, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, K. A. (2011). ‘This Is Religious Environment Sacred Space’, Environmental Discourses,and Environmental Behavior at a Hindu Pilgrimage Site in India. Space and Culture, 14(4),pp.448-463.

- Stoyanov, Y. (2016). The Sacred Spaces and Sites of the Mediterranean in ContemporaryTheological, Anthropological and Sociological Approaches and Debates. In Between CulturalDiversity and Common Heritage, Routledge, pp. 25-36.

- Tripathi, G.; Choudhary, H.; Agrawal, M. What do the tourists want? The case of the Golden Temple, Amritsar. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2010, 2, 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyudie, P.; Antariksa, A.; Wulandari, L.D.; Santosa, H. Place attachment in supporting the preservation of religious historical built environment. IOP Conf. Series: Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winder, A. The “Western Wall” Riots of 1929: Religious Boundaries and Communal Violence. J. Palest. Stud. 2012, 42, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).