Submitted:

26 June 2023

Posted:

27 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant characteristics

| Doctor (N=171) | HCW (N=297) | Total (N=468) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.0009 | |||

| Median (IQR) | 40.0 (34.0, 50.0) | 38.0 (31.0, 46.0) | 38.0 (32.0, 48.8) | |

| Gender | < 0.001 | |||

| Male | 103 (60.2%) | 27 (9.1%) | 130 (27.8%) | |

| Female | 68 (39.8%) | 270 (90.9%) | 338 (72.2%) | |

| Seniority | 0.7013 | |||

| ≤10 years | 91 (53.2%) | 152 (51.2%) | 243 (51.9%) | |

| > 10 years | 80 (46.8%) | 145 (48.8%) | 225 (48.1%) |

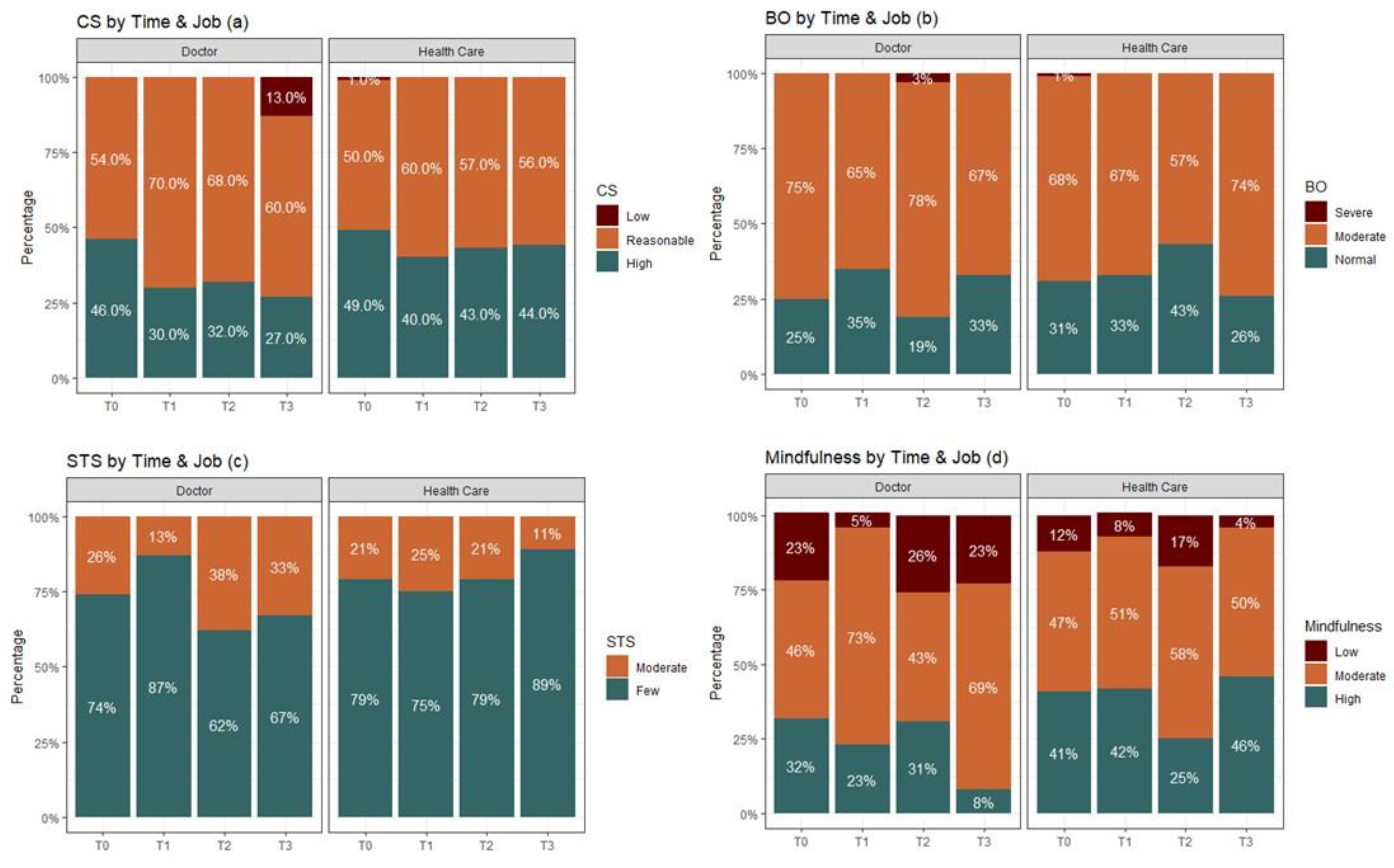

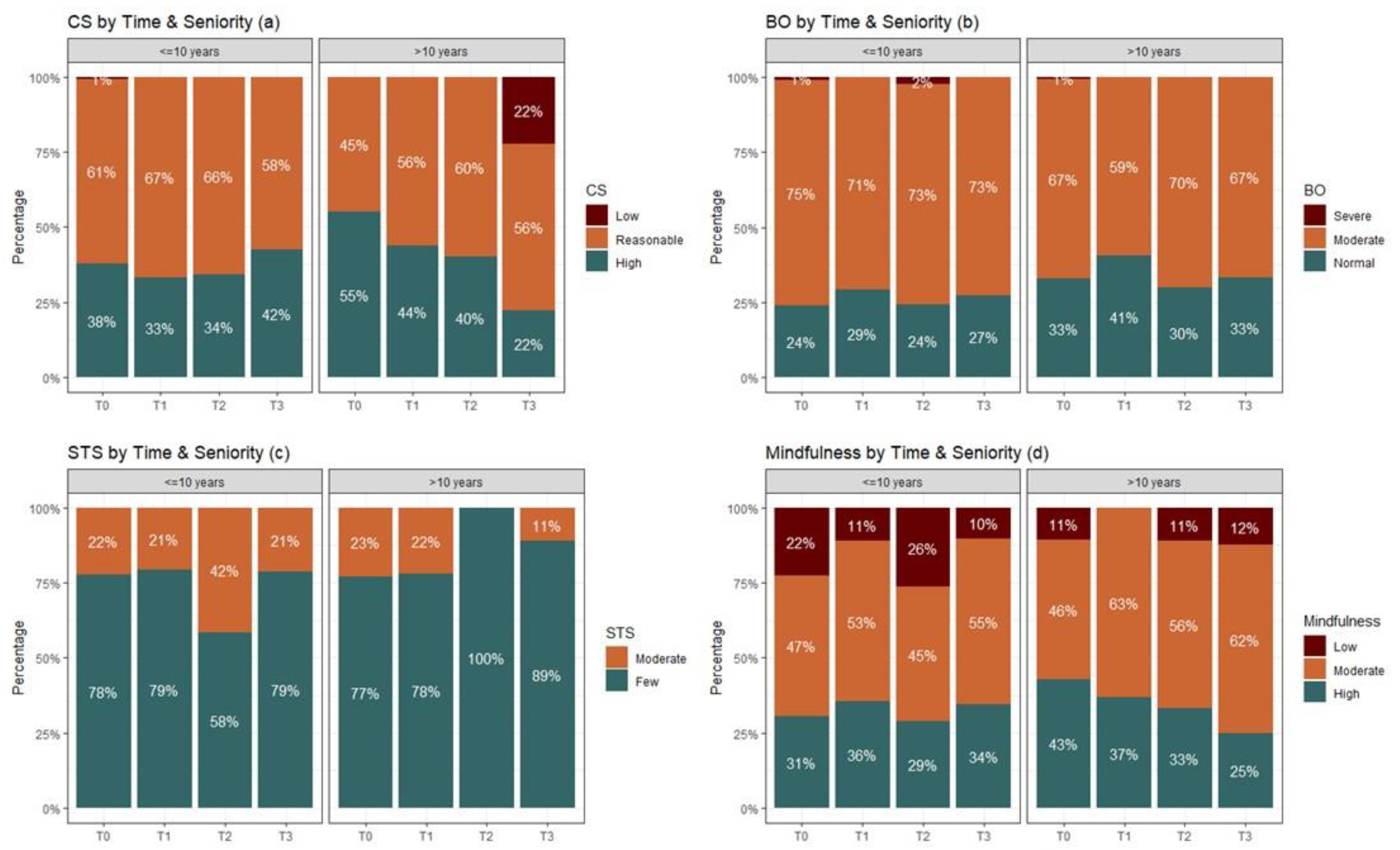

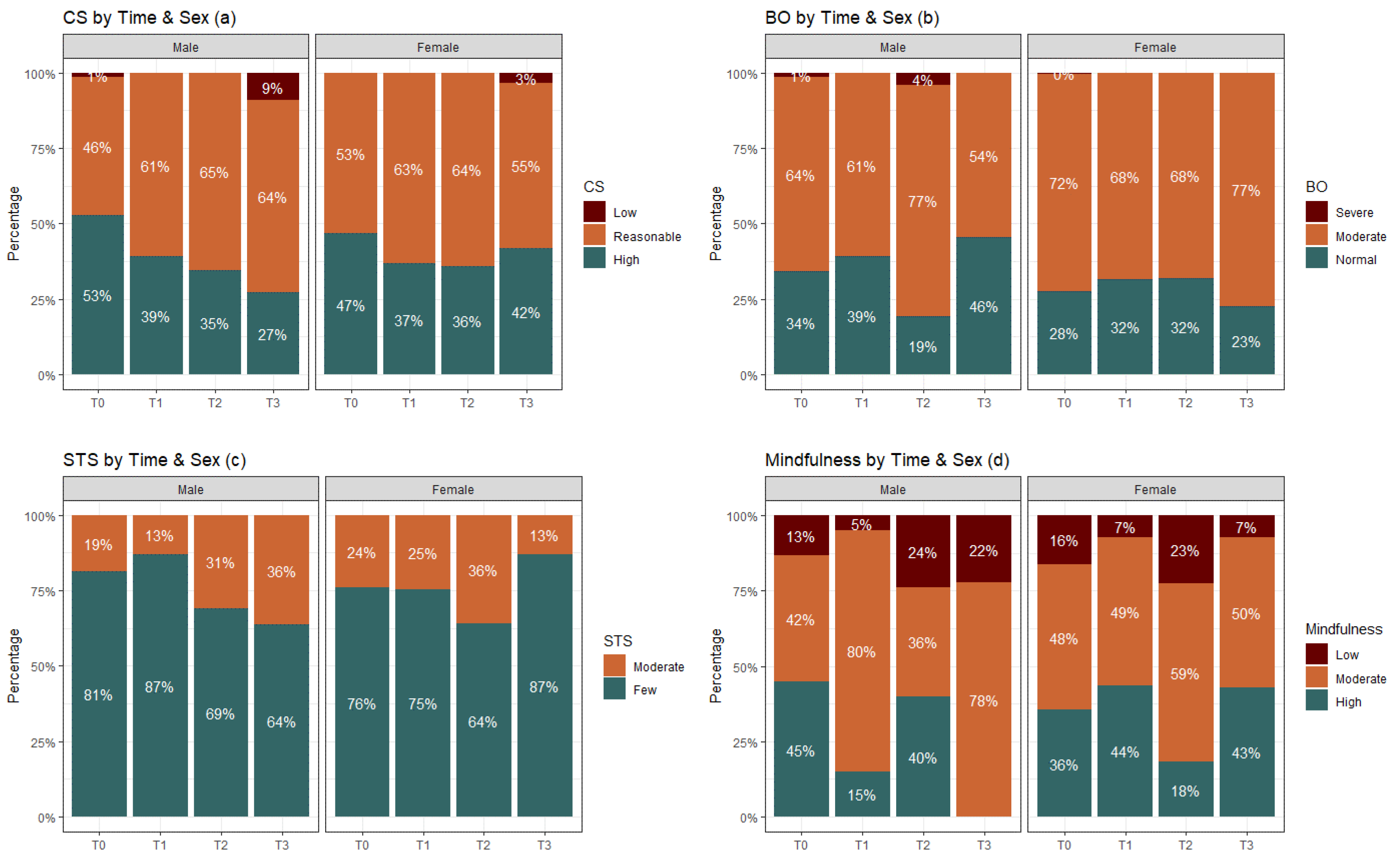

3.2. General effects of phases among doctors & HCW

3.2.1. Compassion satisfaction

3.2.2. Burnout

3.2.3. STS levels

3.2.4. Mindfulness

3.3. Correlations between the ProQOL scales

3.3.1. CS

3.3.2. Burnout

3.3.3. STS

| Doctor | Health Care Workers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P value | 95% CI | r | P value | 95% CI | |||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| CS - burnout | -0.544 | <0.001 | -0.644 | -0.425 | -0.601 | <0.001 | -0.671 | -0.520 |

| CS - STS | -0.179 | 0.019 | -0.325 | -0.025 | -0.149 | 0.010 | -0.262 | -0.033 |

| CS - Mindfulness | 0.205 | 0.009 | 0.048 | 0.353 | 0.280 | <0.001 | 0.162 | 0.390 |

| burnout - STS | 0.475 | <0.001 | 0.346 | 0.587 | 0.423 | <0.001 | 0.322 | 0.515 |

| burnout - Mindfulness | -0.418 | <0.001 | -0.540 | -0.277 | -0.380 | <0.001 | -0.481 | -0.269 |

| STS - Mindfulness | -0.529 | <0.001 | -0.634 | -0.404 | -0.337 | <0.001 | -0.442 | -0.223 |

| Seniority | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 <=10 | 2 >10 | |||||||

| r | P value | 95% CI | r | P value | 95% CI | |||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| CS - burnout | -0.571 | <0.001 | -0.652 | -0.476 | -0.575 | <0.001 | -0.659 | -0.478 |

| CS - STS | -0.235 | <0.001 | -0.354 | -0.109 | -0.052 | 0.437 | -0.185 | 0.083 |

| CS - Mindfulness | 0.299 | <0.001 | 0.171 | 0.418 | 0.187 | 0.007 | 0.048 | 0.320 |

| burnout - STS | 0.436 | <0.001 | 0.325 | 0.536 | 0.436 | <0.001 | 0.320 | 0.539 |

| burnout - Mindfulness | -0.439 | <0.001 | -0.542 | -0.323 | -0.356 | <0.001 | -0.473 | -0.226 |

| STS - Mindfulness | -0.413 | <0.001 | -0.519 | -0.294 | -0.413 | <0.001 | -0.523 | -0.289 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Recommendations

4.3. Contribution to the field

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moreno-Mulet, C.; Sansó, N.; Carrero-Planells, A.; López-Deflory, C.; Galiana, L.; García-Pazo, P.; Borràs-Mateu, M.M.; Miró-Bonet, M. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on ICU Healthcare Professionals: A Mixed Methods Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 9243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raudenská, J.; Steinerová, V.; Javůrková, A.; Urits, I.; Kaye, A.D.; Viswanath, O.; Varrassi, G. Occupational Burnout Syndrome and Post-Traumatic Stress among Healthcare Professionals during the Novel Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2020, 34, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labrague, L.J.; Santos, J.A.A. Fear of COVID-19, Psychological Distress, Work Satisfaction and Turnover Intention among Frontline Nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arpacioglu, S.; Gurler, M.; Cakiroglu, S. Secondary Traumatization Outcomes and Associated Factors Among the Health Care Workers Exposed to the COVID-19. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2021, 67, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunjaya, D.K.; Herawati, D.M.D.; Siregar, A.Y.M. Depressive, Anxiety, and Burnout Symptoms on Health Care Personnel at a Month after COVID-19 Outbreak in Indonesia. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieta, E.; Pérez, V.; Arango, C. Psychiatry in the Aftermath of COVID-19. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2020, 13, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selman, L.E.; Chao, D.; Sowden, R.; Marshall, S.; Chamberlain, C.; Koffman, J. Bereavement Support on the Frontline of COVID-19: Recommendations for Hospital Clinicians. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2020, 60, e81–e86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, C.L.; Wladkowski, S.P.; Gibson, A.; White, P. Grief During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Considerations for Palliative Care Providers. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2020, 60, e70–e76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killikelly, C.; Lenferink, L.I.M.; Xie, H.; Maercker, A. Rapid Systematic Review of Psychological Symptoms in Health Care Workers COVID-19. J. Loss Trauma 2021, 26, 638–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano García, G.; Ayala Calvo, J.C. The Threat of COVID-19 and Its Influence on Nursing Staff Burnout. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 832–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, H.; Malpas, C.B.; Burrell, A.J.; Gurvich, C.; Chen, L.; Kulkarni, J.; Winton-Brown, T. Burnout and Psychological Distress amongst Australian Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Australas. Psychiatry 2021, 29, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferry, A.V.; Wereski, R.; Strachan, F.E.; Mills, N.L. Predictors of UK Healthcare Worker Burnout during the COVID-19 Pandemic. QJM Int. J. Med. 2021, 114, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, R.; Moayedi, S.; Golitaleb, M. COVID-19 Pandemic and Health Anxiety among Nurses of Intensive Care Units. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2020, 29, 1275–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salari, N.; Hosseinian-Far, A.; Jalali, R.; Vaisi-Raygani, A.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Mohammadi, M.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Khaledi-Paveh, B. Prevalence of Stress, Anxiety, Depression among the General Population during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Glob. Health 2020, 16, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, S.Y.; Bugshan, A.S.; Almulhim, K.S.; AlSharief, M.S.; Al-Dulaijan, Y.A.; Siddiqui, I.; al-Qarni, F.D. Knowledge of Dentists, Dental Auxiliaries, and Students Regarding the COVID-19 Pandemic in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Survey. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smallwood, N.; Willis, K. Mental Health among Healthcare Workers during the COVID -19 Pandemic. Respirology 2021, 26, 1016–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orrù, G.; Marzetti, F.; Conversano, C.; Vagheggini, G.; Miccoli, M.; Ciacchini, R.; Panait, E.; Gemignani, A. Secondary Traumatic Stress and Burnout in Healthcare Workers during COVID-19 Outbreak. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva Neto, R.M.; Benjamim, C.J.R.; De Medeiros Carvalho, P.M.; Neto, M.L.R. Psychological Effects Caused by the COVID-19 Pandemic in Health Professionals: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 104, 110062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahebi, A.; Nejati-Zarnaqi, B.; Moayedi, S.; Yousefi, K.; Torres, M.; Golitaleb, M. The Prevalence of Anxiety and Depression among Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 107, 110247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buselli, R.; Corsi, M.; Baldanzi, S.; Chiumiento, M.; Del Lupo, E.; Dell’Oste, V.; Bertelloni, C.A.; Massimetti, G.; Dell’Osso, L.; Cristaudo, A.; et al. Professional Quality of Life and Mental Health Outcomes among Health Care Workers Exposed to Sars-Cov-2 (Covid-19). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 6180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danet Danet, A. Psychological Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic in Western Frontline Healthcare Professionals. A Systematic Review. Med. Clínica Engl. Ed. 2021, 156, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cipolotti, L.; Chan, E.; Murphy, P.; Harskamp, N.; Foley, J.A. Factors Contributing to the Distress, Concerns, and Needs of UK Neuroscience Health Care Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2021, 94, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shechter, A.; Diaz, F.; Moise, N.; Anstey, D.E.; Ye, S.; Agarwal, S.; Birk, J.L.; Brodie, D.; Cannone, D.E.; Chang, B.; et al. Psychological Distress, Coping Behaviors, and Preferences for Support among New York Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiorano, T.; Vagni, M.; Giostra, V.; Pajardi, D. COVID-19: Risk Factors and Protective Role of Resilience and Coping Strategies for Emergency Stress and Secondary Trauma in Medical Staff and Emergency Workers—An Online-Based Inquiry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbay, R.Y.; Kurtulmuş, A.; Arpacıoğlu, S.; Karadere, E. Depression, Anxiety, Stress Levels of Physicians and Associated Factors in Covid-19 Pandemics. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 290, 113130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Man, M.A.; Toma, C.; Motoc, N.S.; Necrelescu, O.L.; Bondor, C.I.; Chis, A.F.; Lesan, A.; Pop, C.M.; Todea, D.A.; Dantes, E.; et al. Disease Perception and Coping with Emotional Distress During COVID-19 Pandemic: A Survey Among Medical Staff. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 4899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, C.S.; Delgado, C.; Catalá, J.; Ferrer, C.; Errando, C.; Iftimi, A.; Benito, A.; De Andrés, J.; Otero, M. ; The PSIMCOV group* COVID-19 Psychological Impact in 3109 Healthcare Workers in Spain: The PSIMCOV Group. Psychol. Med. 2022, 52, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosil Santamaría, M.; Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N.; Redondo Rodríguez, I.; Jaureguizar Albondiga-Mayor, J.; Picaza Gorrochategi, M. Psychological Impact of COVID-19 on a Sample of Spanish Health Professionals. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. Engl. Ed. 2021, 14, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, R.; Socci, V.; Pacitti, F.; Di Lorenzo, G.; Di Marco, A.; Siracusano, A.; Rossi, A. Mental Health Outcomes Among Frontline and Second-Line Health Care Workers During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic in Italy. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2010185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanov, A.; Malobabic, M.; Milosevic, V.; Stojanov, J.; Vojinovic, S.; Stanojevic, G.; Stevic, M. Psychological Status of Patients with Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis during Coronavirus Disease-2019 Outbreak. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2020, 45, 102407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franza, F.; Basta, R.; Pellegrino, F.; Solomita, B.; Fasano, V. The Role of Fatigue of Compassion, Burnout and Hopelessness in Healthcare: Experience in the Time of COVID-19 Outbreak. Psychiatr. Danub. 2020, 32, 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Trumello, C.; Bramanti, S.M.; Ballarotto, G.; Candelori, C.; Cerniglia, L.; Cimino, S.; Crudele, M.; Lombardi, L.; Pignataro, S.; Viceconti, M.L.; et al. Psychological Adjustment of Healthcare Workers in Italy during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Differences in Stress, Anxiety, Depression, Burnout, Secondary Trauma, and Compassion Satisfaction between Frontline and Non-Frontline Professionals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 8358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job Burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalili, M.; Niroomand, M.; Hadavand, F.; Zeinali, K.; Fotouhi, A. Burnout among Healthcare Professionals during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2021, 94, 1345–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitriu, M.C.T.; Pantea-Stoian, A.; Smaranda, A.C.; Nica, A.A.; Carap, A.C.; Constantin, V.D.; Davitoiu, A.M.; Cirstoveanu, C.; Bacalbasa, N.; Bratu, O.G.; et al. Burnout Syndrome in Romanian Medical Residents in Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Med. Hypotheses 2020, 144, 109972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotel, A.; Golu, F.; Pantea Stoian, A.; Dimitriu, M.; Socea, B.; Cirstoveanu, C.; Davitoiu, A.M.; Jacota Alexe, F.; Oprea, B. Predictors of Burnout in Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare 2021, 9, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chor, W.P.D.; Ng, W.M.; Cheng, L.; Situ, W.; Chong, J.W.; Ng, L.Y.A.; Mok, P.L.; Yau, Y.W.; Lin, Z. Burnout amongst Emergency Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Multi-Center Study. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 46, 700–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etesam, F.; Akhlaghi, M.; Vahabi, Z.; Akbarpour, S.; Sadeghian, M.H. Comparative Study of Occupational Burnout and Job Stress of Frontline and Non-Frontline Healthcare Workers in Hospital Wards during COVID-19 Pandemic. Iran. J. Public Health 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanafelt, T.D.; Hasan, O.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Sinsky, C.; Satele, D.; Sloan, J.; West, C.P. Changes in Burnout and Satisfaction With Work-Life Balance in Physicians and the General US Working Population Between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2015, 90, 1600–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, I.; Teixeira, A.; Castro, L.; Marina, S.; Ribeiro, C.; Jácome, C.; Martins, V.; Ribeiro-Vaz, I.; Pinheiro, H.C.; Silva, A.R.; et al. Burnout among Portuguese Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Fernández, M.D.; Ramos-Pichardo, J.D.; Ibáñez-Masero, O.; Cabrera-Troya, J.; Carmona-Rega, M.I.; Ortega-Galán, Á.M. Compassion Fatigue, Burnout, Compassion Satisfaction and Perceived Stress in Healthcare Professionals during the COVID-19 Health Crisis in Spain. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 4321–4330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, M.; Alt, M.; Brooks, J.; Katz, H.; Poje, A. Burnout and Compassion Satisfaction: Survey Findings of Healthcare Employee Wellness During COVID-19 Pandemic Using ProQOL. Kans. J. Med. 2021, 14, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Fernández, M.D.; Ramos-Pichardo, J.D.; Ibáñez-Masero, O.; Carmona-Rega, M.I.; Sánchez-Ruiz, M.J.; Ortega-Galán, Á.M. Professional Quality of Life, Self-compassion, Resilience, and Empathy in Healthcare Professionals during COVID-19 Crisis in Spain. Res. Nurs. Health 2021, 44, 620–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Laar, D.; Edwards, J.A.; Easton, S. The Work-Related Quality of Life Scale for Healthcare Workers: WRQoL Scale for Healthcare Workers. J. Adv. Nurs. 2007, 60, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opollo, J.G.; Gray, J.; Spies, L.A. Work-Related Quality of Life of Ugandan Healthcare Workers: Work-Related Quality of Life in Uganda. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2014, 61, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P.; Taris, T.W. Work Engagement: An Emerging Concept in Occupational Health Psychology. Work Stress 2008, 22, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, K.; Thau, S. Workplace Victimization: Aggression from the Target’s Perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2009, 60, 717–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łoś, K.; Chmielewski, J.; Cebula, G.; Bielecki, T.; Torres, K.; Łuczyński, W. Relationship between Mindfulness, Stress, and Performance in Medical Students in Pediatric Emergency Simulations. GMS J. Med. Educ. 384Doc78 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielewski, J.; Łoś, K.; Łuczyński, W. Mindfulness in Healthcare Professionals and Medical Education. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2021, 34, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, C. The Role of Mindfulness in Medical Practice. Pract. Manag. 2019, 29, 34–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. The Benefits of Being Present: Mindfulness and Its Role in Psychological Well-Being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 822–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, L.E.; Brown, K.W. Validation of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale in a Cancer Population. J. Psychosom. Res. 2005, 58, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, A.; Lamis, D.A.; Bagge, C.L.; Freedenthal, S.; Barnes, S.M. The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale: Further Examination of Dimensionality, Reliability, and Concurrent Validity Estimates. J. Pers. Assess. 2016, 98, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, S.; Johanson, M.M.; Guchait, P. Employees Intent to Leave: A Comparison of Determinants of Intent to Leave versus Intent to Stay. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosil, M.; Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N.; Redondo, I.; Picaza, M.; Jaureguizar, J. Psychological Symptoms in Health Professionals in Spain After the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 606121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, Z.; Zeinoun, P. Self-Compassion Explains Less Burnout Among Healthcare Professionals. Mindfulness 2020, 11, 2542–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadpour, M.; Ghorbani, V.; Khoramnia, S.; Ahmadi, S.M.; Ghvami, M.; Maleki, M. Anxiety, Self-Compassion, Gender Differences and COVID-19: Predicting Self-Care Behaviors and Fear of COVID-19 Based on Anxiety and Self-Compassion with an Emphasis on Gender Differences. Iran. J. Psychiatry 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhadi, M.; Msherghi, A.; Elgzairi, M.; Alhashimi, A.; Bouhuwaish, A.; Biala, M.; Abuelmeda, S.; Khel, S.; Khaled, A.; Alsoufi, A.; et al. Burnout Syndrome Among Hospital Healthcare Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Civil War: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 579563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barello, S.; Graffigna, G. Caring for Health Professionals in the COVID-19 Pandemic Emergency: Toward an “Epidemic of Empathy” in Healthcare. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercadillo, R.E.; Díaz, J.L.; Pasaye, E.H.; Barrios, F.A. Perception of Suffering and Compassion Experience: Brain Gender Disparities. Brain Cogn. 2011, 76, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarnell, L.M.; Neff, K.D.; Davidson, O.A.; Mullarkey, M. Gender Differences in Self-Compassion: Examining the Role of Gender Role Orientation. Mindfulness 2019, 10, 1136–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degeling, P.; Kennedy, J.; Hill, M. Mediating the Cultural Boundaries between Medicine, Nursing and Management - the Central Challenge in Hospital Reform. Health Serv. Manage. Res. 2001, 14, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dev, V.; Fernando, A.T.; Kirby, J.N.; Consedine, N.S. Variation in the Barriers to Compassion across Healthcare Training and Disciplines: A Cross-Sectional Study of Doctors, Nurses, and Medical Students. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 90, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suleiman, A.; Bsisu, I.; Guzu, H.; Santarisi, A.; Alsatari, M.; Abbad, A.; Jaber, A.; Harb, T.; Abuhejleh, A.; Nadi, N.; et al. Preparedness of Frontline Doctors in Jordan Healthcare Facilities to COVID-19 Outbreak. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).